Abstract

We study the folding mechanism of a triple β-strand WW domain from the Formin binding protein 28 (FBP28) at atomic resolution with explicit water model using replica exchange molecular dynamics computer simulations. Extended sampling over a wide range of temperatures to obtain the free energy, enthalpy, and entropy surfaces as a function of structural coordinates has been performed. Simulations were started from different configurations covering the folded and unfolded states. In the free energy landscape a transition state is identified and its structures and φ-values are compared with experimental data from a homologous protein, the prolyl-isomerase Pin1 WW domain. A stable intermediate state is found to accumulate during the simulation characterized by the carboxyl-terminal β-strand 3 having misregistered hydrogen bonds and where the structural heterogeneity is due to nonnative turn II formation. Furthermore, the aggregation behavior of the FBP28 WW domain may be related to one such misfolded structure, which has a much lower free energy of dimer formation than that of the native dimer. Based on the misfolded dimer, aggregation to form protofibril structure is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The α-helix and the β-strand are two basic secondary structural motifs in proteins. Learning their folding mechanism would help to further our understanding of the protein folding process (1). Thus, many experimental and theoretical studies have concentrated on model systems rich in one particular secondary structural motif (2–7). The WW domain families, named after the two conserved tryptophan residues, are the smallest natural β-sheet structures. They are compact protein domains ranging from 35 to 40 amino acids that fold into twisted triple-stranded antiparallel β-sheet structures (8,9). WW domains are abundantly present in eukaryotic cells and involved in various signaling pathways and may also be involved in a number of disease pathologies (10).

The WW domain has been an extensively used model for investigating both thermodynamic and kinetic principles that govern β-sheet folding and stability. Most of these studies have aimed to investigate factors contributing to the β-sheet formation, e.g., hydrogen bonding (11), hydrophobic effects (12), and electrostatic interactions (13). The folding kinetics of WW domains from the human Yes-associated protein (YAP) and the protein prolyl-isomerase (Pin1) can be well described by a two-state folding model (12,14). Recently, the folding kinetics of the Formin binding protein 28 (FBP28) WW domain was probed by laser temperature jump and continuous flow measurements. Unlike the folding kinetics of the other two WW domains mentioned above, a third state has to be considered to account for the kinetic heterogeneity observed in these experiments of the FBP28 WW domain (15). At low temperatures there are apparently two decay phases in the kinetics of the folding of wild-type FBP28, the fast one is ∼30 μs and the slow one is >900 μs. In subsequent work, Fersht and co-workers (16) found that the 40-residue murine FBP28 WW domain rapidly formed twirling ribbon-like fibrils at physiological temperature and pH, with morphology typical of amyloid fibrils and proposed that the observed biphasic kinetics might be related to this aggregation.

The above experimental findings provided impetus for us to explore the folding mechanism of the FBP28 WW domain by molecular dynamics (MD) computer simulation tools at the atomic level. Although the FBP WW domain is small, having only 37 amino acids, its folding rate prevents a thorough sampling of its folding/unfolding configurations by such conventional single long trajectory MD simulations which have showed great potential in studying peptides (17,18). Thus, an enhanced sampling method has to be considered. Recently, the replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) algorithm described by Sugita and Okamoto (19) was shown to be successful in unraveling the configuration space of complex systems (20–25). In this study we apply the REMD simulation to the FBP28 WW domain aiming to shed light on the microscopic picture of folding. From the simulation results, the free energy as a function of structural parameters describing the protein folding/unfolding events over a broad range of temperatures is characterized. A stable intermediate ensemble of misfolded states, characterized by a misregistered strand 3 and with nonnative contacts in turn II is identified. It is suggested that this structural heterogeneity in the free-energy landscape adds complexity to the system that may be related to biphasic unfolding and to initiation of protofibril aggregation. With a number of experimental studies (11,12,14,15,26,27) available we can make a stringent check of our simulation results and also can make a comparison with other modeling studies on similar systems (28–31).

METHODS

Details of the REMD method and algorithm with applications to peptides can be found elsewhere (32). Here only a brief account is given. M-replicas of the system are distributed over M-processors and each simulated at a different temperature over a broad range. Replicas are coupled to each other via a temperature exchange Monte Carlo procedure. At fixed time intervals, systems of neighboring temperature may exchange their spatial configurations according to a standard Metropolis criterion for the transition probability. This procedure induces a random walk in “temperature space”, which in turn amounts to a random walk in potential energy space, thus allowing sampling of a broad range of configuration space in a short (nanosecond) timescale of M-parallel simulations. This mitigates the problem of the system getting trapped in low energy local minima states inherent in long single ensemble simulations. MD simulations were carried out by using an explicit SPC water model (33), under periodic boundary conditions. The 37-aa system was contained in an octahedral box containing 7,441 water molecules and 22,733 atoms in total. The 10 nuclear magnetic resonance structure ensemble, Protein Data Bank file 1E0L(8) was taken as the folded structures. We used the GROMOS force field version 45a3 (34) and the GROMACS program suit (35,36). A twin-range cutoff of 0.9/1.4 nm was used for the nonbonded interactions and a reaction-field correction with permittivity ɛRF = 54 was employed. The integration step in all simulations was 0.002 ps. Nonbonded pair lists were updated every 10 integration steps. The system was coupled to an external heat bath with a relaxation time of 0.7 ps. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained in length. The solvated systems were subject to 500 steps of steepest-descent energy minimization and a 200 ps molecular dynamics simulation at constant pressure (P) and temperature (T), with P = 1 atm and T = 300 K. The equilibrated system was contained in an octahedral box of side dimension 67.5 Å. All replica calculations were done at constant volume.

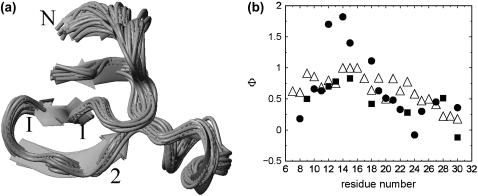

The folded structure is taken from NMR structures Protein Data Bank 1E0L model 1(8) which is shown in Fig. 1. The temperatures of the replicas were chosen to maintain an exchange rate among replicas ∼20%. Exchanges were attempted every 500 integration steps (1 ps). We simulated 88 replicas of the water–protein system, with T from 290.9 to 570.0 K. The procedure of temperature choice is similar to that suggested by other works (37,38). To generate a set of initial conditions that broadly covers the configuration space of the protein, we performed an independent 5-ns high temperature simulation, at T = 600K. We chose 88 configurations at random from this sampling as initial structures for the replicas. The resulting configurations were assigned at random to one of 88 temperatures. The root mean-squared deviations from the NMR structure 1(8) calculated using all atoms (RMSD) covered a range from 1.5 Å to 7.0 Å. All replicas were equilibrated for 200 ps without exchanging temperatures at the beginning of the simulations. The REMD simulation was carried out for 30 ns per replica (2.64 μs total simulation time). The trajectories were saved every 1 ps. The last 25 ns (25,000 configurations) per replica were used to calculate all of the averages reported here.

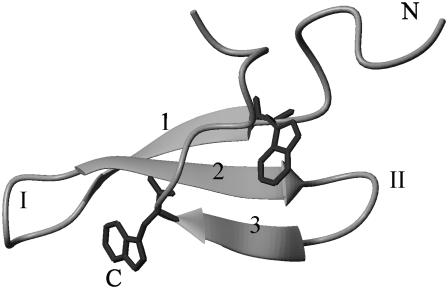

FIGURE 1.

Experimental folded structure from the Protein Data Bank 1E0L model 1(8). N-, C-terminal, strands 1, 2, and 3, and turn I and II are labeled. The side chains of two conserved tryptophan residues (8 and 30) are shown explicitly.

We analyzed the configurations generated in terms of the RMSD, the fraction of native contacts formed (Q), and eight in-registered hydrogen bond (HB) donor-acceptor distances, D1–D8, where backbone hydrogen bonds form in the native state. Contacts were defined as any two atoms within 6.4 Å of each other when two amino acid side chains are separated by five or more amino acids which follows the work by Garcia and Onuchic (21). We found that the choice of threshold of 6.4 Å is not critical and tuning this value within the range 6–7 Å does not change the results qualitatively. We also defined native contacts as all such contacts that exist in the ensemble of the 10 NMR structures. The folded state has 62 native contacts at the residue level. The Q-value is defined as the fraction of native contacts formed in each structure. We monitored the eight in-registered HB distances: D1, the distance between the backbone amide nitrogen of residue 9 (9:N) and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of residue 21(21:O), D2(9:O-21:N), D3(11:N-19:O), D4(11:O-19:N), D5(20:N-29:O), D6(20:O-29:N), D7(22:N-27:O), and D8(22:O-27:N). The first four distances are located between strand 1 and 2, and the last four between strand 2 and 3.

To characterize the transition state (TS) the calculated Φ-value of residue I is defined according to the work of Karplus and co-workers (39) as

|

where NI is the number of native contacts made by residue I in one structure of transition states, and  is the number of native contacts made by residue I in the native state. Experimentally the Φ-value is the ratio of the (de)stabilization of the transition state, ΔΔGTS; to that of the native state, ΔΔGNS for residue I in a mutation measurement.

is the number of native contacts made by residue I in the native state. Experimentally the Φ-value is the ratio of the (de)stabilization of the transition state, ΔΔGTS; to that of the native state, ΔΔGNS for residue I in a mutation measurement.

To study the local turn formation propensity explicitly, four short peptide segments from the turn I (YKTADGKT) and turn II (YNNRTLES) regions of the FBP28 WW domain, the turn II region of the Pin1 WW domain (FNHITNAS) and the turn II region of the YAP WW domain (LNHIDQTT) were simulated independently with explicit water model at temperature T = 300K. Each simulation lasted 40 ns. All peptide chains are amino-acetylated and carboxyl-amidated. The head-to-tail distance between the Cα atom of each terminal is measured to monitor the flexibility and structural heterogeneity of the turn sequence.

The docking study was performed using AutoDock 3.0 (40). A 180 × 180 × 180 grid with 0.5 Å resolution was used. Each experiment performed docking of two static monomer structures that created 100 dimer complexes of which those 20 that have the lowest-binding free energies were selected to calculate the average binding energies.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Potential energy distribution and conformation sampling

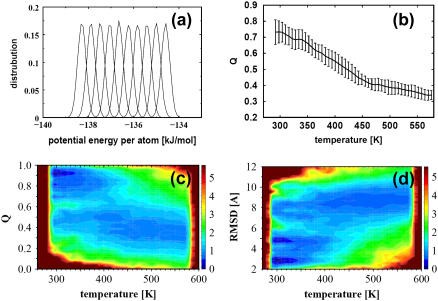

To make the REMD technique work efficiently, the exchange rate between neighboring replicas should be maintained at a reasonable level. Fig. 2 a shows the potential energy distributions averaged over the last 25 ns from the first 10 replicas whose temperatures are in the range from 290.9 K to 311.8 K. There is considerable overlap of potential energy between neighboring replicas resulting in an exchange rate of this REMD simulation around 20%. Although the explicit inclusion of water molecules in the simulation increases the computational load, it also enhances the difference in potential energy between neighboring replicas with different temperatures. For this reason, a large number of replicas (88) have to be chosen to cover the temperature range from 290 K to 570 K and to achieve a small enough potential energy difference between neighboring replicas that will result in the desired exchange rate.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Distributions of potential energy per atom of the first 10 replicas whose temperatures range from 290 K to 340 K. (b) The average fraction of native contacts formed, Q, as a function of the temperature. The error bars are calculated by five-block averages. (c) Relative population of sampled conformations as a function of Q and temperature. (d) Relative population of sampled conformations as a function of RMSD and temperature. The coloring scheme in c and d is based on the free energy-like quantity explained in the main text.

The simultaneous computation with a large number of replicas under different temperatures provided improved sampling. Fig. 2 shows the sampled conformational population as a function of fraction of native contacts Q and temperature (Fig. 2 c) and as a function of RMSD and temperature (Fig. 2 d). Here a two-dimensional grid with respect to Q (or RMSD) and temperature is created to account for the number of sampled conformations in each grid, denoted as Ni. The relative conformational pseudo-free energy, Vi, is calculated in the following way:

Vi = −0.60 × log(Ni/Nmax), where 0.60 comes from RT in units of kcal/mol, T = 300 K, and Nmax is the largest number of conformations counted. The color scheme based on the Vi value is shown in the color contour side labels. The data in Fig. 2, c and d, display the appearance of a minimum at low temperature and Q-values and RMSD ∼0.9 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively, corresponding to the ensemble of native folded structures. In the high temperature region there is a broad valley in the surface of relative conformational population corresponding to the unfolded ensemble of structures. Interestingly, at low temperature and for Q-values and RMSD around 0.8 Å and 5 Å, respectively, an additional ensemble of (misfolded) structures may be discerned. In the following sections, we analyze the structural configurations that have been sampled over the temperature range in the REMD simulations by calculating the free-energy surface as a function of these two structural parameters (Q and RMSD) at a given temperature.

Fig. 2 b shows the melting curve which plots the average of Q as a function of temperature. The relatively larger statistical errors of Q in the lower temperature range (ΔQ is ∼ 1.5 at T = 300 K compared with ΔQ ≈ 0.7 at T = 550 K) indicate that the refolding process is slow at lower temperature and it is difficult to get the unfolding-folding equilibrium during this simulation time. The transition temperature, T*, derived from Q at 0.6 is 375 K, which is higher than the transition midpoint value, 337 K, reported by Nguyen and co-workers (15). The high transition temperature predicted here indicates that there are higher fractions of native contacts at high temperature which is consistent with other studies (21,24) using constant volume REMD. Recently, a constant pressure REMD study on a short β-hairpin also showed that there is a larger fraction of native-like conformations at high temperatures (41). The reason could be ascribed to the force fields which usually are parameterized at room temperature and not for high-temperature simulations.

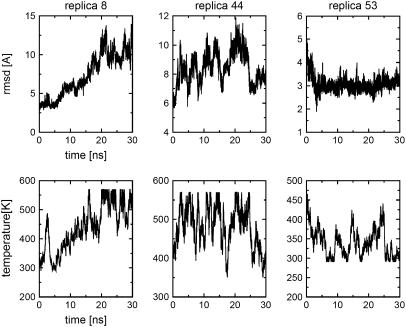

To illustrate the ample and detailed sampling of the folding/unfolding events obtained by the REMD simulations, Fig. 3 shows the time history of temperature and RMSD for three representative replicas (replicas 8, 44, and 53). Replica 8 shows a complete unfolding transition from the folded states (RMSD = 3 Å) to unfolded states (RMSD = 10 Å) and the temperature walks from 300 K to nearly 600 K. Replica 44 shows multiple transitions between the RMSD = 6 Å and RMSD = 10 Å. Its temperature fluctuates between 400 K and 600 K. Replica 53 shows folding event from RMSD = 5–3 Å and its temperatures are between 300 K and 400 K. These trajectories cover a large region of the configuration space. Because of the variations in temperature used in the REMD algorithm, the time history of the replicas is not directly related to the folding/unfolding pathways at constant temperature, but it provides a reasonable description of the order during folding events.

FIGURE 3.

Trajectories of RMSD and temperature as a function of time, sampled by replicas 8, 44, and 53.

Thermodynamic description of the folding energy landscape

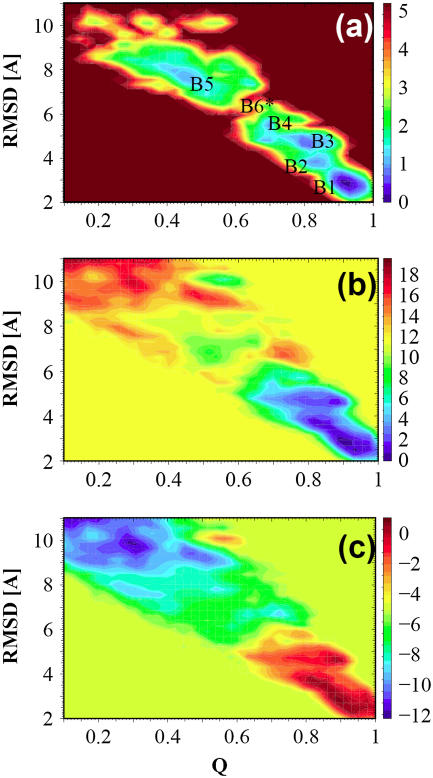

Free energy surfaces were calculated using the histogram-analysis method from the occurrence of the selected order parameters (Q and RMSD) in the generated ensemble of configurations. This method enables the free energy to be projected onto any progress variable dependent on the configuration of the system. Fig. 4 a shows the free energy landscape at 300 K. The coloring scheme is similar to that of Fig. 2 c. Five local minima on the surface are identified and labeled as B1–B5. Table 1 lists the relative free energies of these conformational ensembles. Also listed in Table 1 are the average in-registered HB donor-acceptor distances D1–D8 of these structural ensembles.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Free energy landscape, ΔG, as a function of Q and RMSD for temperature 300 K. (b) The enthalpy contribution ΔH and (c) entropy contribution, −TΔS, T = 300 K. All coloring labels are in units of kcal/mol.

TABLE 1.

Center positions of local minima (basins) of the free energy surfaces (as a function of Q and RMSD), the average distances of in-registered backbone hydrogen bond donor (N)-backbone hydrogen bond acceptor (O), and the relative free energies of the basins

| Center

|

Average distances of in-registered HB donor (N)-HB acceptor (O) (Å)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | RMSD(Å) | Q | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | ΔG(kcal/mol) |

| 10 NMR structures | 1.42(2.20) | 1 | 2.96 | 2.83 | 2.85 | 2.77 | 3.06 | 2.96 | 2.63 | 2.81 | |

| B1 | 2.95 | 0.91 | 2.99 | 3.03 | 3.03 | 2.96 | 3.07 | 3.29 | 3.08 | 3.50 | 0 |

| B2 | 3.87 | 0.81 | 2.97 | 3.17 | 2.99 | 2.93 | 7.04 | 8.04 | 8.17 | 5.43 | 0.73 |

| B3 | 4.64 | 0.81 | 3.76 | 3.78 | 4.98 | 5.87 | 6.75 | 4.97 | 5.19 | 4.36 | 0.36 |

| B4 | 5.54 | 0.68 | 3.15 | 3.36 | 3.08 | 2.97 | 13.63 | 12.11 | 10.20 | 7.89 | 0.84 |

| B5 | 7.59 | 0.46 | 12.41 | 10.28 | 8.32 | 7.71 | 12.82 | 11.93 | 10.63 | 6.74 | 0.64 |

| B6* | 6.15 | 0.64 | 4.48 | 4.54 | 6.51 | 6.83 | 11.23 | 10.57 | 9.33 | 5.52 | 3.48 |

The B6* is the largest energy barrier.

The basin B1 is the global minimum which is located at Q = 0.9 with a RMSD = 2.9 Å. It corresponds to the ensemble of native structures. Due to its small size, this protein domain is quite flexible. The average pairwise RMSD between the 10 NMR structures (8) is 1.41 Å and the maximum is 2.2 Å. Another criterion for identification of this minimum as the native ensemble of local structures comes from the 8 average in-registered HB donor-acceptor distances, D1–D8, which are all close to 3 Å. From the simulations all backbone hydrogen bonds which characterize the antiparallel three-stranded β-sheet structure are maintained in this global minimum structure. The basin B5 that is centered around Q = 0.5 and RMSD = 7.6 Å corresponds to an ensemble of unfolded states. All the average distances D1–D7 of this ensemble are in the region 6–13 Å.

Fig. 4, b and c, display the decomposition of the free energy into its enthalpic and entropic components by simply fitting all free energy surfaces at all sampled temperatures to the function

|

where H and S are the enthalpy and entropy of the system, respectively, as a function of the Q and RMSD parameters. H and S are assumed to be temperature-independent which is a reasonable approximation for such a small protein domain (42). These quantities are the changes in the total enthalpy and entropy of the system with contributions from both protein and solvent. ΔH spans a range of values from 0 to18 kcal/mol, where the folded basin has low enthalpy and the unfolded state has high enthalpy. The entropic free energy contribution, −TΔS, shows opposite behavior, with low entropic contribution for the folded state and high entropic contribution for the unfolded state. The entropic contribution near Q = 0.3 and RMSD = 10 Å is the lowest which indicates the largest structural heterogeneity that has been sampled in the simulations. Due to the crude approximation used, the decomposition of enthalpy and entropy can be considered only qualitatively rather than quantitatively. On the other hand, such approximation is acceptable because most of the results in this study are analyzed based on the free energy and not on enthalpy and entropy. Thus, a more refined analysis, assuming e.g., that the heat capacity is linearly dependent on temperature does not seem warranted.

Transition state

On the free energy landscape the barrier around Q = 0.6, RMSD = 6 Å, labeled as B6*, separates the folded and unfolded states. We assign this barrier region as the transition state. Its free energy is higher than that of the native state by 3.48 kcal/mol (Table 1). If a two-state model is employed, the folding rate of this protein domain can be estimated as

|

where ν is the viscosity-corrected frequency factor, for which we use the value 20 MHz, based on experimental observations of minimal chain-diffusion times (43). From this we estimate kf to be ∼0.058 MHz and the folding time is predicted to be 17 μs, which is reasonably close to the experimentally determined fast folding phase around 30 μs (15).

An ensemble of structures located around the transition state with Q = 0.6 and RMSD = 6 Å at temperature = 300 K is identified from the simulation trajectories and shown in Fig. 5 a. From the snapshots it can be seen that the loop I and the β-sheet structure between strands 1 and 2 are formed and that the residues in the loop II are already in proximity although the β-sheet structure between strands 2 and 3 is not formed. To get more quantified descriptions of the transition state and to compare with the available experimental results, the Φ-values are calculated. Unfortunately, we cannot find experimental Φ-values for the FBP28 WW domain, although experimental values of one of its homologies, the Pin1 WW domain, are abundant (11). We use these Φ-values for comparison as shown in Fig. 5 b. There are two types of experimental Φ-values, one type is from side chain mutations shown by solid circle symbols, the other from amide-to-ester mutations shown by solid square symbols. The calculated Φ-values are represented by open triangle symbols. The overall agreement between the calculated and the experimental values is good. The Φ-values of the loop I region from residue 12 to 16 are highest, close to 1. Φ-Values decrease going to the C-terminal and fall below 0.5 for the residues 26–30. The configuration of the transition state we find here is consistent with those obtained by Φ-value measurements of the Pin1 and YAP WW domains (12,14). The transition state is characterized by the formation of turn I. This agreement is consistent with recent findings that proteins with similar structures but low-sequence identity can fold in similar ways (44–46). Thus, the REMD sampling strategy provides a partial resolution of the structural heterogeneity of the transition state.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Ensemble of structures of the transition state. (b) Comparison of the calculated Φ-values (▵) with the experimental determined Φ-values for the Pin1 WW domain, solid circles for side chain mutation results, and solid squares for amide-to-ester mutation results (11).

Folding intermediate and misfolded states

The local minima of B2 and B4 can be characterized as high-energy transient intermediates. The D1–D8 distances in Table 1 show that the β-sheet structure between strand 2 and 3 is lost and the β-structure between strand 1 and 2 remains intact and they can thus be identified as partially folded states. The local minimum of B3 is interesting because the free energy of the related ensemble is just marginally (0.36 kcal/mol) higher than that of the native state. Like the stable trajectories maintaining native structure, several trajectories forming the B3 basin have small RMSD fluctuations (∼4.6 Å), which mean that the structures are highly stabilized as in the native case. The temperatures of these trajectories are in the region from 290 K to 390 K and once formed at low temperature they are very stable for extended time during the simulations. From the free energy surface (Fig. 4 a) it seems that the energy barrier between B3 and B1 is small and the interconversion between B1 and B3 conformations is a fast event. However, that is not the case kinetically. During the 30-ns simulation we do not observe any event of conformational transformation from B3 to B1. Therefore care should be taken when interpreting the free energy surface obtained by projecting it onto a small number of reaction coordinates, when the free energy is intrinsically of high-dimensional nature.

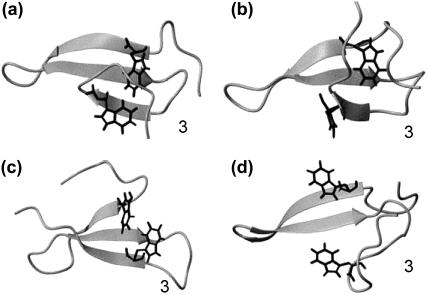

Due to the small RMSD fluctuations in these trajectories, the average structures from the final 1-ns simulation are taken as the representative structures for this ensemble, the four most stable ones of which are shown in Fig. 6, a–d. These four structures all have native-like strand 1, turn I and strand 2, but the structures of turn II and strand 3 are different. In native structures the amino acids Y20 and N22 in strand 2 make backbone hydrogen bonds with T29 and E27 of strand 3, respectively. One intermediate structure, Fig. 6 a shows that Y20 and N22 are hydrogen bonded with W30 and S28, respectively, and turn II is thus one amino acid longer than the native one. In another representative structure (Fig. 6 b), Y20 and N22 are hydrogen bonded with E31 and T29. As a result, strand 3 slides on strand 2 inward by two amino acids and the turn II becomes larger. Fig. 6 c shows another structure in which the stand 3 has moved inward by 3 amino acids, resulting in Y20 and N22 making hydrogen bonds with K32 and W30, respectively, and an enlarged turn II. The structure shown in Fig. 6 d gives an example in which strand 3 has lost the β-structure and interacts with the C-terminus through a loop. The difference between the structures of Fig. 6 d and the transition state in Fig. 5 a, is that there are still native-like contacts in loop II and between strand 2 and strand 3 in the structure shown in Fig. 6 d. In the transition state such contacts are lost.

FIGURE 6.

Representative structures of the misfolded FBP28 WW domain, a, b, c, and d. Strand 3 makes misregistered hydrogen bonds with strand 2, with one, two, and three amino acids shifted in a, b, and c, respectively. In the misfolded structure (d), the strand 3 makes a U-turn.

The ensemble B3 we find here is a misfolded ensemble. The misfolded part is located in turn II and strand 3 and stabilized by misregistered hydrogen bonds and nonnative hydrophobic interactions. On the free energy surface this intermediate state is resolved by a separate basin around Q = 0.8 and RMSD = 4.6 Å and is nearly as stable as the native state. Due to its relative stability this intermediate state can function as a kinetic trap in the folding process which may lead to biphasic folding kinetics and that may also initiate aggregation.

To check the reliability of the B3 structures, separate MD simulation studies of each misfolded structures shown in Fig. 6, a–d, with a different force field, CHARMM27 (47), were undertaken. Each trajectory lasted 5 ns. All four structures remained intact during the simulation which indicates that the misfolded states should not be an artifact caused by force field imperfectness. Regarding the long-range electrostatic interaction a previous study (48) showed that the reaction field correction which is used in this study works well and does not provide artificial results for peptide folding compared with the more rigorous particle mesh Ewald summation method (49).

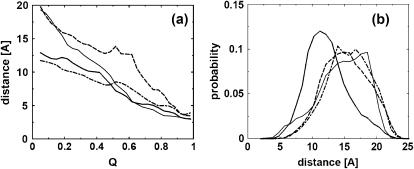

Folding mechanism: local versus nonlocal interactions

Folding a β-strand requires a detailed balance between local interactions, such as turn formation, and nonlocal interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic core collapse. With the extensive sampling of configurations covered by the REMD simulations the folding mechanism of this model β-strand system may be explored. Four distances are utilized to monitor the local and nonlocal interactions: D1, D4, D5, and D8. D1 monitors the interaction of two residues separated by 11 amino acids and can be taken as an indicator of nonlocal interactions between strand 1 and strand 2. D4 describes the local interaction of turn I. D5 monitors the nonlocal interactions between strand 2 and strand 3 and D8 measures the local interactions of turn II.

To determine the role played by the local and nonlocal interactions in the folding process, the average values of the four distances are plotted as a function of Q at the transition temperature T* = 376 in Fig. 7 a. In the unfolded states, Q < 0.5, all distances are >7 Å. When Q approaches 0.6 where the transition state is located, D1 and D4 both approach 5 Å whereas D5 and D8 are still >7 Å. It is shown that in the transition state, turn I is formed and turn II is not. The folding of turn I is completed simultaneously with both local and nonlocal interactions. The formation of turn II is related to larger Q. The local interactions in turn II are formed around Q = 0.8 and the nonlocal interactions are formed at Q = 0.9.

FIGURE 7.

(a) Distances as a function of Q averaged at the transition temperature T = 375 K. Solid, dotted, dashed, and dotted-dashed lines represent D1: the distance between amide nitrogen of residue 9 and carbonyl oxygen of residue 21 (9:N–21:O); D4, 11:O—19:N; D5, 20:N—29:O; and D8, 22:O—27:N. (b) The distribution of the probability of head-to-tail distance for peptide segments taken from FBP28 turn I (solid line), FBP28 turn II (dotted line), Pin1 turn II (dashed line), and YAP turn II (dotted-dashed line).

Turn formation heterogeneity of different sequences

Although similar in size, the folding kinetics of two other WW domains, YAP and Pin1, show single exponential folding kinetics unlike that of the FBP28 WW domain. Based on this study we propose the existence of a stable intermediate state with a misregistered strand 3 that adds complexities to the folding free-energy surface. It is plausible that the heterogeneity of the strand 3 conformation is related to nonnative interactions and heterogeneity of turn II. To investigate this hypothesis, we studied separately the conformational properties of short peptide segments taken from turn II of the FBP28, Pin1 and YAP WW domains. For comparison the corresponding peptide segment taken from turn I of FBP28 was also investigated. Simulations of the four peptides with an explicit water model were made for 40 ns.

The head-to-tail distance of a short peptide can be used to monitor the flexibility and structural heterogeneity of a turn sequence and thus gives an indication of turn formation propensity of a given sequence. Fig. 7 b shows the results from turn I of FBP28 (YKTADGKT), turn II of FBP28 (YNNRTLES), turn II of Pin1 (FNHITNAS), and turn II of YAP (LNHIDQTT). None of the peptides contain the proline residue which favors turn structure. All the peptides display extended structures with a peak position of the head-to-tail distance >10 Å. The distribution curve of the FBP28 turn II displays a peak position around 10 Å, which is different from all the other curves located around 16 Å, suggesting a tendency of this peptide to preorganize its conformation. This is mainly caused by an ionic bond formed between two charged side chains of R24 and E27. In the native structures the distance between these two side chains is large (∼14 Å) and R24 is in close vicinity of E7 to help closing the turn I. Thus, it is possible that the nonnative interaction between R24 and E27 could play a role for misfolding of turn II.

Comparison with other simulation studies

The folding time of a β-strand is usually longer than that of an α-helix, which makes theoretical modeling work studying β-strand folding more challenging (3). Several groups have applied MD thermal unfolding methods studying WW domains and found that the strand 2 and strand 3 are the first to separate in the unfolding process (26,50). The intermediate states we find here only exist at low temperature. The replica-exchange algorithm used in this study provides an advanced sampling and a physical distribution of structural ensembles under a broad range of temperatures. This study was encouraged by the successful folding mechanism study of the α-helical protein A using a similar replica-exchange algorithm by García and Onuchic (6,21).

Brooks and co-workers (25,26) have studied the same FBP28 WW domain at different levels of modeling. In one study, Karanicolas and Brooks (29) studied the WW domain folding kinetics using sequence-dependence Cα-based Go-like models and found that the mobility of the third β-strand may contribute to the biphasic kinetics. This finding is consistent with this study and with other thermal unfolding studies (26,50). To obtain a more detailed picture of the folding process, Karanicolas and Brooks (28) revisited the FBP28 WW domain. They used a biased-sampling method with an all-atom model and with implicit representation of the solvent. The main conclusion of their study is that the FBP28 WW domain may adopt two slightly different forms of packing in its hydrophobic core (28). What we find here is an extension of their finding. Due to the misfolding of turn II, this domain takes different hydrophobic packing forms. Moreover, we propose that the different folding kinetics of the WW domain in FBP28 as compared to Pin1 and YAP may be related to the presence of an ensemble of misfolded structures in the free energy landscape, characterized by the heterogeneous turn II formation of FBP28 and a misregistered strand 3. In the FBP28 WW domain there are oppositely charged amino acids located in the turn II region (RTLE). This motif is also found in other WW domains (8,51). The CA150 WW1 and WW2 domains have RTRE and RTLE motifs in the same position, respectively (51). In the Ned4 Human protein there is a ESRR motif in the WW domain 1 (Swiss-Prot sequence code P46934).

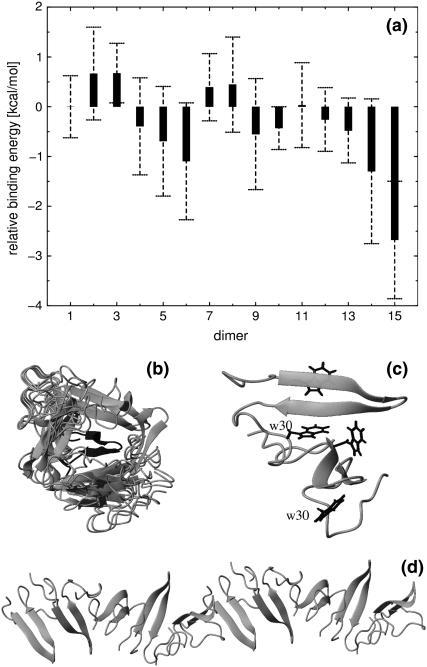

Aggregation initiation and protofibril structure

Fersht and co-workers (16) found that the FBP28 WW domain rapidly formed twirling ribbon-like fibrils at physiological temperature and pH, with morphology typical of amyloid fibrils and proposed that the biphasic kinetics observed for the FBP28 WW domain by Kelly and co-workers (15) might be related to this aggregation. In light of this finding and because of the interest in WW domains as model systems for proteins forming aggregated β-sheet amyloid fibrils, it is of relevance to compare the aggregation properties of the native and misfolded type of structures that were found in the MD simulations. The predicted free energy of binding for dimer formation can be used as an indicator of the potency of aggregation initiation. The average binding energies of the 15 dimers of structures from the native and misfolded structures a) – d) that were identified from the B3 ensemble were studied by docking pairs of such static structures, the result of which is shown in Fig. 8 a. The average binding free energy of the homodimer of the native structure is taken as reference (set to zero). The binding free energy of all homodimers of misfolded structures is lower than that of the native structure. The homodimer of the misfolded type d is the most stable one, with a binding energy 2.6 kcal/mol lower than that of the native structure. Although the docking method gives a highly approximate free energy of binding and the absence of conformational degrees of freedom does not allow for flexibility to optimize the structure of the docked monomers, it is suggestive that the misfolded structures give lower binding energies that the native one.

FIGURE 8.

(a) Relative binding energies of dimers, calculated by averaging the lowest 20 docking energies from 100 docked configurations for each dimer. The labels indicate different dimers with 1–15 representing the dimer of N-N, N-a, N-b, N-c, N-d, a-a, a-b, a-c, a-d, b-b, b-c, b-d, c-c, c-d, and d-d, respectively, of which N symbolizes the native state. a, b, c, and d refer to the misfolded structures a, b, c, and d shown in Fig. 6. (b) Superposition of 20 misfolded-type-d-formed (Fig. 6) homodimer structures, which have the lowest binding energy; the target monomer is shown in the middle with dark color. (c) One homodimer structure formed by the misfolded type d in Fig. 6. Four tryptophan residues are shown, of which the two W30 are labeled. (d) A protofiber chain consisting of 10 monomers formed in the same way as the dimer does in c.

Fig. 8 b shows a superposition of those 20 type d homodimer structures that have the lowest binding energies. We can classify these structures into two groups. In group 1 the stacking direction of the two monomers is parallel with the direction of the backbone HBs on the β-strands of each monomer. The docked monomers in this group are located below or above the target monomer shown in Fig. 8 b. The stacking direction of the monomers in the other group is perpendicular to the direction of the backbone HBs, to the left and right sides of the target monomer.

On the basis of the group 1 stacking it is possible to build a polymer with the axis parallel to the direction of HBs of the β-sheet, as illustrated by a typical dimer structure in Fig. 8 c. The two β-strand surfaces of monomers are nearly perpendicular to each other with a large twist angle ∼72°. The W30 residue is located at the interface making a hydrophobic contact with Y11 of the next monomer. There is a salt bridge between K17 and E10 of the next monomer. By repetition of this dimer pattern a protofibril model made of 10 units is shown in Fig. 8 d. The diameter of the fiber rod is measured to be ∼25 Å consistent with cryoelectron microscopy observations (16). This kind of amyloid aggregate may serve as an intermediate structure formed during the initial fibril formation process. Recently intermediate β-sheet structures of amyloid peptides were characterized by solid-state NMR spectroscopy (52) and these aggregation patterns may be relevant to such initial protofibrils.

CONCLUSIONS

We have studied the folding mechanism of the FBP28 WW domain at atomic resolution with explicit water model. Using replica exchange molecular dynamics we perform extensive sampling over a wide range of temperatures to obtain the free energy, entropy, and enthalpy surfaces as a function of structural reaction coordinates. Turn I is found to be formed in the transition state although turn II is not. An intermediate state is found to have structures characterized by misfolded turn II and misregistered strand 3, which makes the free energy landscape more complicated at room temperature. The reason why only FBP but not Pin1 or YAP was found to have biphasic folding kinetics in experiments can be explained by this intermediate state that may act as a trap in the folding process. Based on a comparison of the relative binding free energy of the native dimer with dimers of the misfolded structures, a structural model for the FBP28 WW aggregation and protofibril formation has been proposed.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Prof. Alan Fersht, who provided insightful instructions and comments.

The support of a Lee Kuan Yew Research Fellowship to Y.G.M. is acknowledged. This work has been supported by the Singapore Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) through a Biomedical Research Council grant to L.N. and J.P.T., and the National Natural Foundation of China (No. 90203013) to Y.G.M. The simulations were performed on the Compaq Alpha supercomputer cluster of the Bioinformatics Research Centre at Nanyang Technological University, which is acknowledged for generous allocation of computer time.

References

- 1.Fersht, A. 1998. Enzyme Structure, Mechanism & Protein Folding, 3rd ed. W. H. Freeman, New York.

- 2.Ferrara, P., and A. Caflisch. 2000. Folding simulations of a three-stranded antiparallel beta-sheet peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:10780–10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubelka, J., J. Hofrichter, and W. A. Eaton. 2004. The protein folding ‘speed limit’. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou, Y., and M. Karplus. 1999. Interpreting the folding kinetics of helical proteins. Nature. 401:400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz, V., P. A. Thompson, J. Hofrichter, and W. A. Eaton. 1997. Folding dynamics and mechanism of beta-hairpin fromation. Nature. 390:196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato, S., T. L. Religa, V. Daggett, and A. R. Fersht. 2004. Testing protein-folding simulations by experiment: B domain of protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:6952–6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe, D. R., V. Hornak, and C. Simmerling. 2005. Folding cooperativity in a three-stranded β-. sheet model. J. Mol. Biol. 352:370–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macias, M. J., V. Gervias, C. Civera, and H. Oschkinat. 2000. Structural analysis of WW-domains and design of a WW prototype. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanelis, V., D. Rotin, and J. D. Forman-Kay. 2001. Solution structure of a Nedd4 WW domain-ENaC peptide complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudol, M. 1996. The WW domain binds polyprolines and is involved in human diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 28:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deechongkit, S., H. Nguyen, E. T. Powers, P. E. Dawson, M. Gruebele, and J. W. Kelly. 2004. Context-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to beta-sheet folding energetics. Nature. 430:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager, M., H. Nguyen, J. C. Crane, J. W. Kelly, and M. Gruebele. 2001. The folding mechanism of a β-sheet: the WW domain. J. Mol. Biol. 311:373–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schleinkofer, K., U. Wiedemann, L. Otte, T. Wang, G. Krause, H. Oschkinat, and R. C. Wade. 2004. Comparative structural and energetic analysis of WW domain-peptide interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 344:865–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane, J. C., E. K. Koepf, J. W. Kelly, and M. Gruebele. 2000. Mapping the transition state of the WW domain β-sheet. J. Mol. Biol. 298:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen, H., M. Jager, A. Moretto, M. Gruebele, and J. W. Kelly. 2003. Tuning the free-energy landscape of a WW domain by temperature, mutation, and truncation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:3948–3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson, N., J. Berriman, M. Petrovich, T. D. Sharpe, J. T. Finch, and A. R. Fersht. 2003. Rapid amyloid fiber formation from the fast-folding WW domain FBP28. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9814–9819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daura, X., W. F. van Gunsteren, and A. E. Mark. 1999. Folding-unfolding thermodynamics of a beta-heptapeptide from equilibrium simulations. Proteins. 34:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mu, Y. G., P. H. Nguyen, and G. Stock. 2005. Energy landscape of a small peptide revealed by dihedral angle principal component analysis. Proteins. 58:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugita, Y., and Y. Okamoto. 1999. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee, Y. M., and V. S. Pande. 2003. Multiplexed-replica exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding simulation. Biophys. J. 84:775–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia, A. E., and J. N. Onuchic. 2003. Folding a protein in a computer: an atomic description of the folding/unfolding of protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13898–13903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gnanakaran, S., H. Nymeyer, J. Portman, K. Y. Sanbonmatsu, and A. E. Garcia. 2003. Peptide folding simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou, R., B. J. Berne, and R. Germain. 2001. The free energy landscape for beta hairpin folding in explicit water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:14931–14936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou, R. 2003. Trp-cage: folding free energy landscape in explicit water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13280–13285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou, R., and B. J. Berne. 2002. Can a continuum solvent model reproduce the free energy landscape of a beta-hairpin folding in water? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:12777–12782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson, N., J. R. Pires, F. Toepert, C. M. Johnson, Y. P. Pan, R. Volkmer-Engert, J. Schneider-Mergener, V. Daggett, H. Oschkinat, and A. Fersht. 2001. Using flexible loop mimetics to extend Phi -value analysis to secondary structure interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:13008–13013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deechongkit, S., P. E. Dawson, and J. W. Kelly. 2004. Toward assessing the position-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to beta-sheet folding thermodynamics employing amide-to-ester perturbations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:16762–16771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karanicolas, J., and C. L. Brooks. 2004. Integrating folding kinetics and protein function: Biphasic kinetics and dual binding specificity in a WW domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:3432–3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karanicolas, J., and C. L. Brooks. 2003. The structural basis for biphasic kinetics in the folding of the WW domain from a formin-binding protein: Lessons for protein design? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:3954–3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonvin, A., and W. F. van Gunsteren. 2000. β-hairpin stability and folding: molecular dynamics studies of the first β-hairpin of tendamistat. J. Mol. Biol. 296:255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson, N., C. M. Johnson, M. Macias, H. Oschkinat, and A. Fersht. 2001. Ultrafast folding of WW domains without structured aromatic clusters in the denatured state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:13002–13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsutake, A., Y. Sugita, and Y. Okamoto. 2001. Generalized-ensemble algorithms for molecular simulations of biopolymers. Biopolymers. 60:96–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berendsen, H. J. C., J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, and J. Hermans. 1981. Intermolecular forces. B. Pullman, editor. The Netherlands.

- 34.Chandrasekhar, I., M. Kastenholz, R. D. Lins, C. Oostenbrink, L. D. Schuler, D. P. Tieleman, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 2003. A consistent poptential energy parameter set for lipids: dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine as a benchmark of the GROMOS 45a3 force field. Eur. Biophys. J. 32:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berendsen, H. J. C., D. van der Spoel, and R. van Drunen. 1995. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindahl, E., B. Hess, and D. van der Spoel. 2001. Gromacs 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Model. 7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanbonmatsu, K. Y., and A. E. Garcia. 2002. Structure of Met-enkephalin in explicit aqueous solution using replica exchange molecular dynamics. Proteins. 46:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen, P. H., Y. G. Mu, and G. Stock. 2005. Structure and energy landscape of a photoswitchable peptide: a replica exchange molecular dynamics study. Proteins. 60:485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paci, E., M. Vendruscolo, C. M. Dobson, and M. Karplus. 2002. Determination of a transition state at atomic resolution from protein engineering data. J. Mol. Biol. 324:151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris, G. M., D. S. Goodsell, R. S. Halliday, R. Huey, W. E. Hart, R. K. Belew, and A. J. Olson. 1998. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seibert, M. M., A. Patriksson, B. Hess, and D. van der Spoel. 2005. Reproducible polypeptide folding and structure prediction using molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 354:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myers, J. K., C. N. Pace, and J. M. Scholtz. 1995. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 4:2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapidus, L. J., W. A. Eaton, and J. Hofrichter. 2000. Measuring the rate of intramolecular contact formation in polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:7220–7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez, J. C., and L. Serrano. 1999. The folding transition state between SH3 domains is conformationally restricted and evolutionarily conserved. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plaxco, K. W., S. Larson, I. Ruczinski, D. S. Riddle, E. C. Thayer, B. Buchwitz, A. R. Davidson, and D. Baker. 2000. Evolutionary conservation in protein folding kinetics. J. Mol. Biol. 298:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riddle, D. S., V. P. Grantcharova, J. V. Santiago, E. Alm, I. Ruczinski, and D. Baker. 1999. Experiment and theory highlight role of native state topology in SH3 folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:1016–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacKerell, A. D., D. Bashford, M. Bellott, R. L. Dunbrack, J. D. Evanseck, M. J. Field, S. Fischer, J. Gao, H. Guo, S. Ha, D. Joseph-McCarthy, L. Kuchnir, K. Kuczera, F. T. K. Lau, C. Mattos, S. Michnick, T. Ngo, D. T. Nguyen, B. Prodhom, W. E. Reiher, B. Roux, M. Schlenkrich, J. C. Smith, R. Stote, J. Straub, M. Watanabe, J. Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera, D. Yin, and M. Karplus. 1998. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baumketner, A., and J.-E. Shea. 2005. The influence of different treatments of electrostatic interactions on the thermodynamics of folding of peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:21322–21328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Essmann, U., L. Perera, M. L. Berkowitz, T. Darden, H. Lee, and L. G. Pedersen. 1995. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibragimova, G. T., and R. C. Wade. 1999. Stability of the beta-sheet of the WW domain: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Biophys. J. 77:2191–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstrohm, A. C., T. R. Albrecht, C. Sune, M. T. Bedford, and M. A. Garcia-Blanco. 2001. The transcription elongation factor CA150 interacts with RNA polymerase II and the pre-mRNA splicing factor SF1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7617–7628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chimon, S., and Y. Ishii. 2005. Capturing intermediate structures of Alzheimer's by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:13472–13473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]