Abstract

Two mesophilic/thermophilic variants of the G-domain of the elongation factor Tu were studied via molecular dynamics simulations. By analyzing the simulation data via the Voronoi space tessellation, we have found that the two proteins have the same macromolecular packing, while the water-exposed surface area is larger for the thermophile. A larger coordination with water is probably due to a peculiar corrugation of the exposed surface of this species. From an enthalpic point of view, the thermophile shows a larger number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, stronger electrostatic interactions, and a flatter free-energy landscape. Overall, the data suggest that the specific hydration state enhances macromolecular fluctuations but, at the same time, increases thermal stability.

INTRODUCTION

Living organisms can stand a wide variety of thermodynamic conditions. Those adapted to ambient temperature, pH, and salinity are named mesophilic. Thermophilic species are operative under extreme temperatures (1), even exceeding the boiling temperature of water such as for the Pyrococcus furiosus bacteria. Up to now a satisfactory understanding of the origins of adaptation at extreme conditions remains elusive. The comprehension of thermophilic and mesophilic behavior is crucial since it may provide relevant information on the evolutionary aspects involved and on the general mechanisms underlying protein stability. Moreover, it may help in the design of thermostable biomolecules for technological applications, as in food conservation, detergency, and therapeutic antibody production.

In past years, several authors have investigated the physical basis of protein stability focusing on the systematic differences encountered when comparing the primary sequence of mesophilic and thermophilic homologs. Generally speaking, the primary sequence of thermophilic species is characterized by a higher proportion of polar and hydrophilic amino acids and a preference for the charged hydrophilic and the hydrophobic residues in lieu of the hydrophilic uncharged ones (2,3). However, mesophilic and thermophilic homologs often share the same folded structure (4) and there is no evidence that amino acidic composition alone could be responsible for thermal stability (5). Nevertheless, two main causes for protein stability have been put forward: 1), an increased packing of the hydrophobic residues (6); and 2), stronger interactions between polar residues due to electrostatic contributions and/or hydrogen bonds (5,7–10).

In calorimetric studies ΔCp has been measured to confront mesophilic and thermophilic counterparts, in particular at the unfolding transition. Heat capacity ΔCp is the quantity that allows us to probe the energetic landscape, since it is related to the free energy convexity (ΔCp = −T2d2G/dT2) and provides a measure of protein stability (11). On a number of variants, a smaller heat capacity in thermophiles has been systematically observed upon unfolding (see (12) and references therein). Since both species present maximal stability at approximately room temperature and a free energy minimum that stabilizes thermophiles by ∼1–2 kcal/mol, it has been speculated that thermostability is related to a free energy stability curve characterized by the same temperature at the minimum but a broader landscape. The explanation of such difference in the free energy curve is based on the presence of a residual structure during thermal denaturation of the thermophile or, alternatively, on the different hydrophobic/hydrophilic content of the two variants. In the first interpretation the presence of a residual structure would prevent complete hydration of apolar amino acids and consequently lower heat capacity of the unfolded state (13–15). However, this explanation is in conflict with the higher optimum temperature of thermophiles and with the surplus of hydrophilic amino acids. Alternatively, since a positive heat capacity is a signature of solvation of hydrophobic amino acids, while small negative contributions generally arise from solvation of hydrophilic solutes, a surplus of polar residues would lower the heat capacity (16,17).

From these physico-chemical data it emerges that not only the structural properties of the macromolecules, but the hydrophobic effect, i.e., on the water-mediated interactions mutually exerted among amino acids, can be responsible for thermostability. Both reasons can alter the energetics of the solute by few kcal/mol or fractions thereof, thus resulting in a shift of unfolding temperatures by tens of Kelvins. Water is a fundamental element for the correct folding and functioning of proteins (18,19). The interactions at the protein-water interface depend on the degree of hydrophobicity of the exposed amino acids. Around the polar ones the water layer is generally characterized by a hydrogen-bond (HB) network with hydrogen-bonding residues. The apolar amino acids are surrounded by collagen-water, mainly constituted by weak HB-connecting water molecules (20). X-ray data have shown that thermophilic species present larger hydrophilic exposed surfaces as compared to mesophilic counterparts (21).

From the morphological point of view, the nature of the interactions between a hydrophobic surface and water depends on the shape and ruggedness of the exposed surface (22,24). According to the Lum-Chandler-Weeks theory of hydrophobicity (23), differences in the curvature of the protein-water interface alters protein stability due to collective water depletion that appears at length scales of 1 nm or larger. On the other hand, Berne and co-workers have recently shown that the protein-water interface cannot be interpreted as an idealized hydrophobic surface (24). The model by Hummer et al. (25) explains unfolding based on the pressure exerted by water on the protein-exposed surface. According to the model, unfolding is due to the transfer of water into the protein hydrophobic core that progressively breaks hydrophobic contacts and swells the protein interior. Differently stated, if pressure overcomes a given threshold, water percolates inside the protein matrix and destabilizes the structural scaffolding (26). Along these lines, we have recently shown that unfolding of a mesophile is preceded by an enhanced exchange of interfacial water molecules with the bulk (27). The liquidlike behavior of interfacial water would eventually trigger diffusion of water inside the protein and therefore unfolding.

The scenario underlying protein stability apparently depends on many independent factors—the amino acidic sequence, the types of amino acids exposed to the solvent, the morphology, and energetics of the interfacial region. In this work we aim at obtaining a detailed microscopic characterization of the thermal response of two closely related proteins, namely the G-domain of an ubiquitous protein named elongation factor (Tu) belonging to two organisms, Escherichia coli (mesophilic) and Thermus thermophilus (moderately thermophilic), respectively. The first organism presents living temperature between 35 and 40°C, the second one adapted to temperatures of ∼70–75°C. We investigate the two G-domains via molecular dynamics simulations by performing a comparative analysis of the structural organization of the two solutes, the microdetails of the protein-water interface and their energetics.

METHODS

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a powerful computational tool to investigate solvated proteins with a high degree of physical realism. We have undertaken an extended series of MD simulations of the two proteins at eight different temperatures to obtain a systematic picture of the two species. We simulate the GTP binding regions of the elongation factor Tu, also named G-domain, of Escherichia coli (28) and Thermus thermophilus (29). The thermophilic organism is found in hot springs of neutral to alkaline pH, and grow at 70–75°C (30). The temperatures of the native environment of the two organisms are 37 and 75–80°C, respectively, with denaturation temperatures differing by ≈40°C (13,15). The Tu protein is composed by three domains and it is well known that their thermal stability depends on the mutual interactions. Thermal response of the separated G-domain is generally measured by the inactivation of the GTP or GDP binding. In the case of E. coli, the activity maximum is at ∼15°C and the half-inactivation temperature is at 26–29°C (31). On the other hand, the G-domain of T. thermophilus has an activity maximum at 27°C and half-inactivation temperature at 41°C (32). Therefore, the optimal functioning temperature of the two G-domains differ by ∼12°C.

The two G-domains present a rather strong alignment in primary sequence (Table 1) and basically the same amount of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids, with net charges equal to 17 and 12 e, respectively. By a first inspection, the three-dimensional structures appear to be globular and similar in size, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison in hydrophobic/hydrophilic composition between the mesophilic and thermophilic G-domains

| Mesophile | Thermophile | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of amino acids | 196 | 194 |

| No. of hydrophobic amino acids | 57 | 57 |

| Sequence alignment | 85% | |

FIGURE 1.

Three-dimensional representations of the water-exposed surfaces of the mesophilic (left panel) and thermophilic (right panel) G-domains, obtained via the Connolly construction (33). Different shades of gray correspond to different atoms (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur).

All simulations and analyses are performed with the DLPROTEIN simulation package (34). The CHARMM22 force field is used to model the protein interatomic forces (35) and the TIP3P force field (36) to model water. Other force fields can reproduce more accurately conformational rearrangements (37) but the CHARMM22 force field is expected to be accurate in reproducing the protein-water interface. The energetics and the dielectric constant of the model (38,39) are in good agreement with the experimental data (82 instead of 80), while the diffusion and expansion coefficients are 2.2 and 3.6 times larger, respectively, than the experimental values, and a density maximum at T = 260 K instead of 278 K.

The two G-domains are simulated with periodic boundary conditions with a consistent treatment of electrostatics. The long-range nature of the Coulomb potential are handled via the Ewald summation method (40). The real-space implementation known as the smooth particle-mesh Ewald method (41) is used to compute electrostatics very efficiently. The method is used with an α-switching parameter of 0.318, a grid resolution of 10 nm−1, and a spline order of 8. All nonbonding interaction terms are cut off beyond a distance of 0.9 nm, with a shifted potential van der Waals interaction and further smoothed by a polynomial switching function in the range of 0.5 nm before the cutoff.

The hydrated G-domains are simulated in the isobaric-isothermal ensemble by using the Nosé-Hoover style equations of motion (42,43) with volume allowed to fluctuate in an isotropic way. Coupling between the coordinates and momenta and the thermostating and barostating variables are achieved with characteristic times of 0.5 and 5.0 ps, respectively.

We adopt a time-reversible extension of the velocity Verlet algorithm to integrate in time the equations of motion (44), by using a single time-step scheme with an integration time of 2 fs. All chemical bonds do not change in time by enforcing holonomic constraints (in particular the water model is represented as a rigid body). All constraints are imposed by the SHAKE algorithm (40), with modifications in the NPT ensemble, as described in Martyna et al. (44).

The mesophile and thermophile are surrounded by 2929 and 2906 water molecules, respectively. The hydrated system are studied at temperatures T = 240, 255, 270, 285, 300, 330, 360, and 390 K and pressure of 1 atm. At each temperature, we initially equilibrated the hydrated proteins for 200 ps and subsequently simulated the systems for 5 ns.

A central issue in the simulation of proteins pertains to the length of the MD trajectory. The sampling attitude of our simulations and the mechanical stability of the macromolecular structures are monitored by computing the root mean-square displacement (RMSD) of the protein configuration {ri} with respect to a reference structure {ri(to)}. The RMSD is defined as

|

where the minimum is obtained over roto-translating the dynamical structure {ri(t)}. If the system does not properly sample equilibrium, simulation results may differ considerably from the true equilibrium data. This warning applies if the initial state of the protein is not taken at the same thermodynamic point of the simulation state (e.g., as customarily done when initiating the runs from crystallographic data). In our case, moreover, we have initially removed part of the TU factor to extract the G-domain. Therefore, we carefully monitor the RMSD by performing a forward and a backward time analysis. Following the methodology described in Stella and Melchionna (45), we compute the RMSD with the reference structure taken as the initial structure (forward) or the final structure (backward) extracted from the MD run. Backward analysis is usually more informative, since it allows us to observe directly the very initial process of approaching equilibrium.

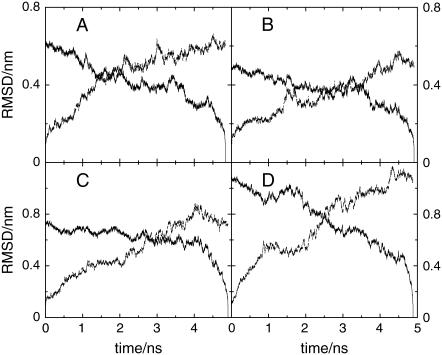

In Fig. 2 the time-dependent RMSDs at temperatures of 300 and 330 K are presented. The two chosen temperatures are representative of the regimes observed at T ≤ 300 K and T ≥ 330 K for both species. The backward time analysis shows that the first 2 ns of the trajectories correspond to the initial relaxation, whereas the last 3 ns of the trajectory can be considered for subsequent analysis. Therefore, at both temperatures we deem the simulation trajectories long enough to observe nonlocal conformational rearrangements. In particular, below 300 K the two proteins appear to sample their native state for a sufficiently long time, whereas at higher temperatures the evolution toward unfolding can be recognized. It should be noted that both proteins exhibit an unfolding trend at 330 K as expected for both species; in particular, the experimental unfolding temperature of the thermophile is well below the simulation value. Consistently, the initial stage of unfolding appears to have a longer characteristic time for the thermophile (data not shown). We have taken the last 3 ns of the runs as representative for the subsequent data analysis at all temperatures.

FIGURE 2.

Root mean-square displacement at T = 300 K for the mesophile (A) and thermophile (B) and T = 330 K for the mesophile (C) and thermophile (D) versus time. The forward time evolution and backward time evolution can be distinguished as being the RMSD zero for initial and final times, respectively.

From auxiliary analysis of the time evolution of the secondary structure, we observe that for T ≤ 300 K the protein structures appear to be stationary and compact throughout the simulation time span. From visual inspection of the macromolecular structures, we do not observe any presence of water molecules deeply buried inside the protein core. At high temperatures the situation is different, since the slow rupture of the protein structure allows for a large amount of water to enter the core region.

RESULTS

Our first analysis focuses on the microscopic characterization of the protein packing attitude and the protein-water interfacial region for the two homologs. We compute the volume occupied by the solutes and the protein-water interfacial region by employing the Voronoi construction to partition the space into atom-based polyhedra (46,47). The set of all polyhedra, also known as Wigner-Seitz cells for crystals, is a spacefilling tessellation that provides an unambiguous and accurate measure of the protein-occupied volume, as shown by comparison with sound velocity measurements (48). Each Voronoi (convex) polyhedron is constructed by finding its vertices, each vertex being identified as the intersection of three planes. The latter are determined as the planes bisecting orthogonally the segments joining the central atom with its neighboring atoms.

Moreover, the Voronoi tessellation allows us to qualify the extension of contact surface between protein-protein and protein-water atoms (47). In fact, each face of the Voronoi polyhedra defines a frontier between neighboring atoms, whose area is a good indicator of the exposed surface for intra- and interspecies contacts. Although there are alternative routes to define atomic contacts based on relative distances, we have chosen the Voronoi construction to directly evaluate the exposed surface area, a relevant quantity for biological and disordered materials.

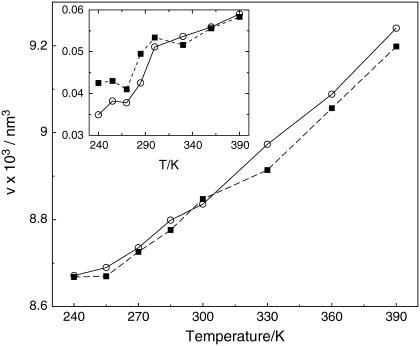

Fig. 3 illustrates the protein volumes per particle of the two homologs versus temperature. The Voronoi volume of the mesophile differs from previously reported data concerning the so-called molecular volume (27), computed via the Richards construction (49), i.e., by adding artificial solvent molecules around the protein to emulate hydration. In this work, the spacefilling Voronoi tessellation considers the complete configuration of the hydrated system. The two curves are monotonic and grow almost linearly above 255 K. Importantly, in the 240 ≤ T ≤ 300 K range the specific volumes of the two G-domains are practically identical, thus ruling out the possibility that different packing of the solutes is a major actor in setting thermal stability. At high temperatures the mesophile swells by ∼1% more than the thermophile. It should be remarked that at low temperatures the volume fluctuations of the thermophile are systematically larger than those of the mesophile by 5–10%. The larger fluctuations of the thermophile represent a recurrent pattern observed when analyzing volumetric data of this species.

FIGURE 3.

Time-averaged specific protein volume for the mesophile (circles) and thermophile (squares) versus T. Lines are reported as a guide for the eye. The volume fluctuations versus T are reported in the inset.

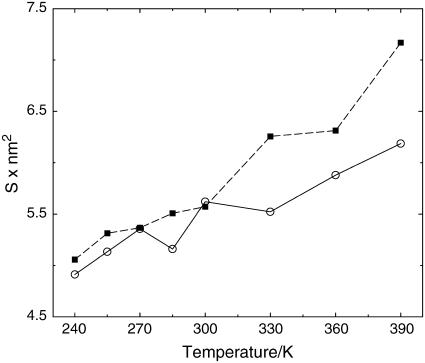

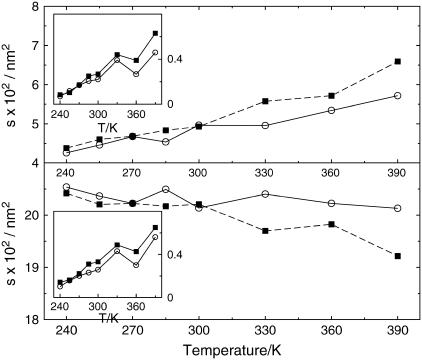

A different morphological characterization of the two proteins is given by the water-exposed surface, a quantity reflecting the shape of the two species and the degree of exposure, i.e., its ruggedness. The data in Fig. 4 show that the thermophile has almost systematically a larger exposed surface, indicating a larger hydrophilic attitude, where the adjective here has only a geometrical meaning. Moreover, whereas the thermophile has a monotonic trend in temperature, the mesophile has a more uncertain behavior at intermediate temperatures.

FIGURE 4.

Time-averaged water-exposed surface of the two G-domains versus T. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

The microscopic view permitted by MD allows us to single out the protein-water interface as well as the intraprotein contacts. Data in Fig. 5 reveal important differences between the mesophile and the thermophile. The trends of the curves for the two species appear quite similar. However, the two species behave similarly only below 300 K, while at higher temperatures the thermophile exhibits more protein-solvent and fewer protein-protein exposed surface. Again, the fluctuations of these quantities are systematically larger for the thermophile.

FIGURE 5.

Time-averaged protein-solvent (upper panel) and protein-protein (lower panel) specific contact areas versus T. The fluctuations of the two quantities versus T are reported in the insets. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

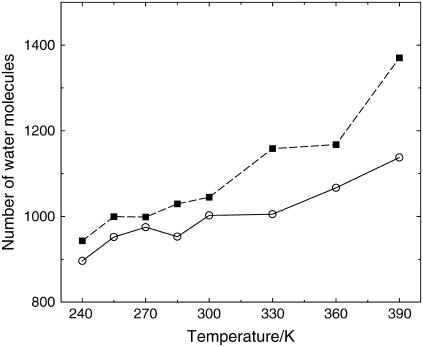

The exposed surface provides a first determination of morphological differences between the two proteins, which are not apparent by a simplistic inspection of the two structures, e.g., obtained by employing a rolling-ball or Connolly construction (33). The data suggest that at high temperatures the larger protein-water contacts of the thermophile, compensated by a smaller intraprotein contact area, corresponds to a larger number of water molecules in contact with the protein. Analysis of the number of water molecules in contact with the protein (Fig. 6), obtained by sorting out the identity of the neighboring Voronoi polyhedra, confirms this hypothesis. At all temperatures the thermophile exhibits a higher number of protein-water contacts and, in particular, at low temperatures it has ∼5% more contacts than the mesophile.

FIGURE 6.

Time-averaged number of water molecules in contact with the protein versus T. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

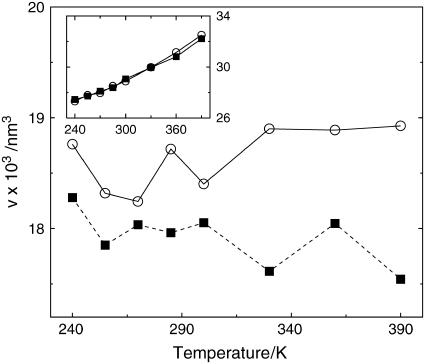

Once the water/protein contacts are identified, we analyze the volume occupied by the interfacial solvent layer, obtained by summing the contribution arising from individual water molecules. The Voronoi volume of atoms belonging to water molecules that are in contact with the proteins are illustrated in Fig. 7. The molecular volume of water having at least one atom in contact with the protein is plotted in the inset. The molecular volumes agree with the values obtained in bulk water for the TIP3P model (0.30 nm3 at T = 300 K) (36). The atomic-based volumes of solvent atoms in contact with the proteins are close to the Van der Waals volumes of oxygen atoms, thus suggesting that the proximal water molecules have oxygens preferentially pointing toward the proteins.

FIGURE 7.

Time-averaged specific volume of atoms belonging to water molecules in contact with the protein versus T. The inset contains the molecular volume per water molecule having at least one atom in contact with the protein. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

The curves show that on an atomic basis, interfacial water around the mesophile has a volume 5% larger than the thermophilic counterpart. Although the curves exhibit some noise, the atomic-based volume of proximal water of the thermophile appears to decrease with temperature, whereas the opposite takes place in the mesophile. At high T, once water penetrates inside the macromolecules the atom-based specific volume takes rather distinct values for the two species. Taken together with the indication that proximal water exhibits the same occupied molecular volume in both species, the data suggest that the water-exposed surface of the thermophile is such to accommodate densely packed atoms belonging to the solvent. Therefore, the surrounding water molecules present peculiar conformations which fit, at best, the corrugation of the thermophilic surface. The packing attitude ameliorates with temperature, in agreement with the findings obtained when analyzing the protein-water contacts.

A more detailed picture of protein-water coordination is obtained by analyzing the population of water molecules whose oxygen atom is located in proximity of any atom of the protein. The water molecules are grouped in histograms based on the number of protein atom neighbors, which are found within a 0.3-nm radius. A broad distribution informs on the number of water molecules that are highly coordinated with the solute, and possibly encapsulated within protein crevices. The histograms in Fig. 8 illustrate the situation at temperatures of 240, 300, and 390 K. The striking feature at all temperatures is the long tail observed for the thermophilic species, i.e., a significant number of water molecules with many contacts with the protein, revealing the enhanced ruggedness of the thermophile.

FIGURE 8.

Histograms grouping the number of water molecules having a number of 1, …, 10 protein atoms with relative distance from the water oxygen smaller than 0.3 nm. The three panels refer to T = 240 K (upper), T = 300 K (mid), and T = 390 K (lower), respectively. Solid and empty bars refer to the mesophilic and thermophilic species, respectively.

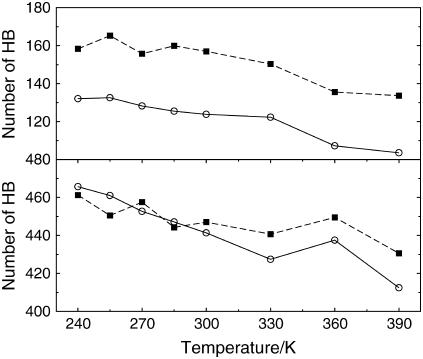

The protein-water energetics and the protein-water hydrogen-bond network are analyzed to distinguish if the hydrophilic character of the thermophile is related to morphological or energetic causes. The occurrence of an HB is detected geometrically when an HB donor and acceptor relative distance is smaller than 0.35 nm and the donor-hydrogen-acceptor angle is >150°. The number of protein-protein and protein-water HBs are reported in Fig. 9. The main difference between the two species relies on the larger amount of intraprotein HB in the thermophile (25% larger than the mesophile), in agreement with the often observed surplus of hydrogen bonds in thermophilic species (12). The intraprotein HBs decrease with temperature for both species, their difference remaining basically constant at all temperatures. The protein-water HBs contain the important feature that the number of hydrogen bonds disrupted by thermal agitation is larger for the mesophile, in particular at T > 300 K.

FIGURE 9.

Time-averaged number of hydrogen bonds. Data refer to protein-protein (upper panel) and protein-water (lower panel) counts, respectively. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

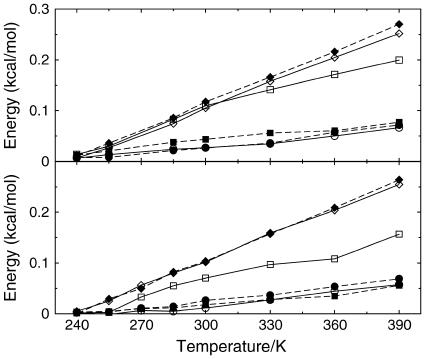

Evaluation of the protein energetics provides partial indications on solvation, since the entropic contributions are not taken into account. However, this analysis allows us to gain a deeper understanding on the meso/thermophilic behavior. We thus compute the chemical, electrostatic, and van der Waals contributions to the potential energy of polar and apolar amino acids. The chemical contributions refer to protein atoms covalently bonded and parameterized by the CHARMM force field and include angular and torsional interactions. The energy curves in Fig. 10 are summed over all atoms belonging to the two amino acids classes and include both protein-protein and protein-water interactions. The energetics shows a linear trend with temperature for both the mesophile and the thermophile, for the chemical and van der Waals contributions arising from polar and apolar amino acids. The most significant difference arises from electrostatics of the polar amino acids. For the mesophile this quantity is regular and shows two regimes, below and above 300 K (see open squares in upper panel, Fig. 10). As previously discussed (27), the crossover is most probably related to the activation of exchange of interfacial water with the bulk. In the case of the thermophile the electrostatics of the polar amino acids has a more irregular behavior, with a slope somehow closer to the high-temperature value of the mesophile (see open squares in lower panel, Fig. 10). However, the mesophile/thermophile pair does not show dramatic differences in enthalpic contributions at all temperatures. It is thus likely that the water-mediated interactions result in a larger entropic contribution for the thermophile, as signaled by the larger fluctuations observed for this species (see, e.g., inset of Fig. 3).

FIGURE 10.

Time-averaged potential energies of amino acids, divided by polar (solid line and open symbols) and nonpolar (dashed line and solid symbols) types, and by van der Waals (circles), electrostatic (squares), and chemical (diamonds) contributions. Each contribution has been shifted by an arbitrary value. Data refer to the mesophile (upper panel) and thermophile (lower panel), respectively.

The activation of exchange of vicinal water molecules with the bulk is best seen by inspecting the number of water molecules resident for >50 ps in the 0.3-nm-thick shell around the protein, shown in Fig. 11. This diagnostic allows us to follow the number of solvent molecules persistently residing in proximity of the protein, as compared to the more mobile solvent molecules in exchange with the bulk. The number of persistent water molecules for both species is low, given by only a few tens, and the values have very similar values for T < 300 K. At low temperatures, thermal agitation progressively reduces the number of resident water molecules in favor of diffusion. Above 300 K the onset of exchange with the bulk is apparent for the mesophile. Vice versa, at high temperatures the thermophilic protein regains efficiency in capturing water molecules, even more than at low temperatures. In this regime, the difference in the number of resident water molecules between the two species is of ∼100% or larger.

FIGURE 11.

Time-averaged number of molecules residing for more than 50 ps in a shell of thickness 0.3 nm around the protein. Symbols are as in Fig. 3.

The presence of high-temperature immobilized water around the thermophile suggests that electrostatic screening of the proximal water molecules is reduced. Although a direct quantification of this effect is beyond the reach of simulation, in the thermophile this effect could generate a larger electrostatic interaction between protein and bulk water, thus increasing the hydrophilic attitude of the thermophile.

DISCUSSION

The general debate around thermostability concentrates on two different possible explanations. The first one is based on the enhanced conformational rigidity arising from better packing of thermophiles and mechanical robustness of the macromolecular scaffolding. Better packing would prevent water molecules from penetrating inside, and thus destabilizing, the protein core. The second explanation advocates the hydrophobic effect in conjunction with the surplus of polar amino acids and salt-bridges as the stabilizing factor in thermophilic homologs. Similarly, calorimetric data on specific heat are interpreted on the basis of the surplus of polar versus apolar amino acids in these species. In some cases, however, experiments have shown that replacement of a buried apolar amino acid by a polar one shifts the unfolding temperature to lower values (50). The crucial information emerging from experimental studies is that thermophiles present a broader and flatter free energy landscape as compared to the mesophiles. Moreover, the temperature optimum of both species coincides (≈300 K), whereas the thermophiles appear to have a larger stabilization free energy.

Our characterization of the two G-domains shed some light on the aforementioned aspects. We recall that the two chosen proteins have basically the same amount of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids and present unfolding temperatures that differ by ∼40 K. Although a localization of the unfolding temperature was beyond the scope of our computational study, we obtained a detailed picture of the macromolecules by evaluating different diagnostics, related to the protein volume, the protein-water interface, and the protein energetics.

Our results do not indicate significant differences in packing between the two homologs, while significant differences have been observed for the exposed surface and intramolecular hydrogen bonds. By inspecting the fluctuations of several volumetric properties related to the protein and its exposure to the solvent, the most important feature characterizing the thermophile is the larger fluctuations with respect to the mesophile. Such enhanced fluctuations could originate from different factors, e.g., a reduced mechanical stability due to intramolecular reasons only. Vice versa, the observation that the number of protein-protein hydrogen bonds is by 25% larger in the thermophilic variant indicates that this species is mechanically robust, no less than the mesophilic counterpart. This datum correlates well with the deeper free energy minimum found experimentally in thermophiles. However, a large amount of hydrogen bonds does not necessarily imply that the protein fluctuations should be reduced. To our opinion, the enhanced flexibility should be related to the enhanced protein-water contacts. As generally recognized, water enhances protein fluctuations by breaking protein-protein in favor of protein-water hydrogen bonds, therefore fluidizing the macromolecular structure. The extreme of water penetration inside the protein core is the disruption of its tertiary structure (25). Moreover, if vicinal water is somehow immobilized, the imperfect electrostatic screening at the protein-water interface can attract more water molecules from the bulk and, thus, the affinity of the protein for water increases (51). Our data showed that the thermophile presents a larger affinity for water, exhibiting a surplus of protein-water HBs (∼20) accompanied by a surplus of protein-protein HBs (≈40). In this sense, the hydrophilic character of the thermophile is larger than the mesophile, despite the same hydrophobic/hydrophilic composition of the two variants.

We further observed that the thermophile exhibits more protein-water contacts and the surrounding water is more densely packed at atomic level. By inspecting the protein-water coordination, we find that water around the thermophile is highly coordinated to the protein. These results indicate that the micromorphology of the water-exposed surface differs substantially between the two variants. In particular, the thermophile-exposed surface is more irregular and capable of capturing more water molecules at the interface than the mesophile. The number of water contacts is systematically larger for the thermophile, and is even larger at higher temperatures where this increment corresponds to a larger number of long-lived resident water molecules. It is interesting to notice that even at low temperatures the thermophile coordinates more water molecules, suggesting that in this regime the surface ruggedness is structural rather then thermally activated. Upon increasing temperature, the ruggedness of the thermophile increases together with the number of resident water molecules. Our data partially agree with model calculations showing that an energy barrier exists for the formation of water-protein bonds and this barrier increases with temperature in hyperthermophilic species (52).

Concerning the microscopic origins of meso/thermophilic behavior, our study indicates that the increased stability of thermophiles is related to efficient stabilization of vicinal water and consequent enhancement of macromolecular conformational fluctuations. In this respect, the paradigm that conformational rigidity implies thermostability has been recently questioned (53,54). On the basis of amide exchange data, it was proposed that conformational fluctuations of thermophiles take place on the timescale of the hydrogen bond rupture so that water has partial access to the protein core. Consequently, the rigidity of the protein structure is not partitioned uniformly on a molecule-wide scale but only in localized regions, such as in the active sites. Neutron spectroscopy on α-amilase has revealed that the short-time motion of the thermophile is characterized by higher structural flexibility (55), implying that conformational entropy is mainly responsible for rendering the free energy curve flatter than in the mesophile. Early molecular dynamics studies on different proteins have reported similar flexibilities between meso/thermophilic homologs (56) or slightly larger fluctuations of the thermophile at high temperatures (57), while recent studies showed larger fluctuations of a thermophile homolog even at low temperatures (58). Yet, the discrepancy between these results can be explained on the basis that different proteins use different mechanisms to achieve thermostability.

Overall, our study supports the notion that water is an ambivalent element for biomolecules. On one hand, water destabilizes proteins due to its efficiency in hydrogen bonding with the macromolecule. On the other hand, vicinal water can act as a bioprotectant with respect to thermal, mechanical, or chemical stress. Therefore, a suggestive interpretation of this study is that the strategy developed by thermophilic species to defend against temperature and, indirectly, water flooding the protein core, is to allow for a small but significant number of water molecules to partially penetrate the protein-water interface. Such tamed water molecules do not exchange with the bulk as for the mesophilic species at high temperatures. The water layer effectively produces a barrier with respect to penetration of other solvent molecules inside the protein core. In summary, the observed differences between the two G-domains are given by the packing at atomic level of the vicinal solvent, and not the protein structural organization. In our opinion, the microdetails of the protein-water interface, the interplay exerted between protein and water, and the mutually induced fluctuations represent a major contribution to thermostability.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to P. Londei and P. Cammarano for suggesting the TU Elongation Factor as a prototypical system for studying thermostability and to T. Head-Gordon and M. Marchi for stimulating discussions.

References

- 1.Adams, M. W. W., and R. M. Kelly. 1995. Enzymes from microorganisms in extreme environments. Chem. Eng. News. 18:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haney, P. L., J. H. Badger, G. L. Buldak, C. L. Reich, C. R. Wose, and G. J. Olsen. 1999. Thermal adaptation analyzed by comparison of protein sequences from mesophilic and extremely thermophilic Methanococcus species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:3578–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haney, P. L., M. Stees, and J. J. Konisky. 1999. Analysis of thermal stabilizing interactions is mesophilic and thermophilic adenylate kinases from the genus Methanococcus. Biol. Chem. 274:28453–28458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szilagyi, A., and P. Zavodsky. 2000. Structural differences between mesophilic, moderately thermophilic and extremely thermophilic protein subunits: results of a comprehensive survey. Struct. Fold. Des. 8:493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maes, D., J. P. Zeelen, N. Thanki, N. Beaucamp, M. Alvarez, M. H. Thi, J. Backman, J. A. Martial, L. Wyns, R. Jaenicke, and R. K. Wierenga. 1999. The crystal structure of trisphosphate isomerase (TIM) from Thermotoga maritima: a comparative thermostability structural analysis of ten different TIM structures. Proteins. 37:441–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li, W. T., J. W. Shriver, and J. N. Reeve. 2000. Mutational analysis of differences in thermostability between histones from mesophilic and hyperthermophilic Archaea. J. Bacteriol. 182:812–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy, S., and M. R. N. Murthy. 2000. Protein thermal stability: insights from atomic displacement parameters (B values). Protein. Eng. 13:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britton, K. L., K. S. P. Yip, S. E. Sedelnikova, T. J. Stillman, M. W. W. Adams, K. Ma, D. L. Maeder, F. T. Robb, N. Tolliday, C. Vetriani, D. W. Rice, and P. J. Baker. 1999. Structure determination of the glutamate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophile Thermococcus litoralis and its comparison with that from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Mol. Biol. 293:1121–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebbink, J. H. G., S. Knapp, J. Van der Oost, D. Rice, R. Landestein, and W. M. de Vos. 1999. Engineering activity and stability of Thermotoga maritima glutamate dehydrogenase. II. Construction of a 16-residue ion-pair network at the subunit interface. J. Mol. Biol. 289:357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogt, G., S. Woell, and P. Argos. 1997. Protein thermal stability, hydrogen bonds, and ion pairs. J. Mol. Biol. 269:631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prabhu, N. V., and K. A. Sharp. 2005. Heat capacity in proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 56:521–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou, H.-X. 2002. Toward the physical basis of thermophilic proteins: linking of enriched polar interactions and reduced heat capacity of unfolding. Biophys. J. 83:3126–3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzman-Casado, M., A. Parody-Morreale, S. Robic, S. Marqusee, and J. M. Sanchez-Ruiz. 2003. Energetic evidence for formation of a pH-dependent hydrophobic cluster in the denatured state of Thermus thermophilus ribonuclease H. J. Mol. Biol. 329:731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robic, S., M. Guzman-Casado, J. M. Sanchez-Ruiz, and S. Marqusee. 2003. Role of residual structure in the unfolded state of a thermophilic protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:11345–11349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motono, C., T. Oshima, and A. Yamagishi. 2001. High thermal stability of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase from Thermus thermophilus resulting from low ΔΔCp of unfolding. Protein Eng. 14:961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Privalov, P. L., and G. I. Makhatadze. 1990. Heat capacity of proteins. II. Partial molar heat capacity of the unfolded polypeptide chain of proteins: protein unfolding effects. J. Mol. Biol. 213:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makhatadze, G. I., and P. L. Privalov. 1995. Energetics of protein structure. Adv. Protein Chem. 47:307–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe, A. J. 2001. Probing hydration and the stability of protein solutions. A colloid science approach. Biophys. Chem. 93:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franks, F. 2002. Protein stability: the value of “old literature”. Biophys. Chem. 96:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walrafen, G. E., and Y.-C. Chu. 2000. Nature of collagen-water hydration forces: a problem in water structure. Chem. Phys. 258:427–446. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, X., W. Meining, M. Fischer, A. Bacher, and R. Ladenstein. 2001. X-ray structure analysis and crystallographic refinement of lumazine synthase from the hyperthermophile Aquifex aeolicus at 1.6 Å resolution: determinants of thermostability revealed from structural comparison. J. Mol. Biol. 306:1099–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandler, D. 2002. Two faces of water. Nature. 417:491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lum, K., D. Chandler, and J. D. Weeks. 1999. Hydrophobicity at small and large length scales. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:4570–4577. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou, R., X. Huang, C. J. Margulis, and B. J. Berne. 2004. Hydrophobic collapse in multidomain protein folding. Science. 305:1605–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummer, G., S. Garde, A. E. García, M. E. Paulaitis, and L. R. Pratt. 1998. The pressure dependence of hydrophobic interactions is consistent with the observed pressure denaturation of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:1552–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Careri, G., A. Giansanti, and J. A. Rupley. 1986. Proton percolation on hydrated lysozyme powders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:6810–6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melchionna, S., G. Briganti, P. Londei, and P. Cammarano. 2004. Water-induced effects on the thermal response of a protein. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92:158101-1–158101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen, G. R., S. Thirup, L. L. Spremulli, and J. Nyborg. 2000. High resolution crystal structure of bovine mitochondrial EF-Tu in complex with GDP. J. Mol. Biol. 297:421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Y., Y. Jiang, M. Meyering-Voss, M. Sprinzl, and P. B. Sigler. 1997. Crystal structure of the EF-Tu EF-Ts complex from Thermus thermophilus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantazaki, A. A., A. A. Pritsa, and D. A. Kyriakidis. 2001. Biotechnologically relevant enzymes from Thermus thermophilus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanderova, H., M. Hulkova, P. Malon, M. Kepkova, and J. Jonak. 2004. Thermostability of multidomain proteins: elongation factors EF-Tu from Escherichia coli and Bacillus stearothermophilus and their chimeric forms. Protein Sci. 13:89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nock, S., N. Grillenbeck, M. R. Ahmadian, S. Ribeiro, R. Kreutzer, and M. Sprinzl. 1995. Properties of isolated domains of the elongation factor Tu from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Eur. J. Biochem. 234:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connolly, M. L. 1983. Solvent-accessible surfaces of proteins and nucleic acids. Science. 221:709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melchionna, S., and S. Cozzini. 2001. The DLPROTEIN User Manual. University of Rome.

- 35.MacKerell, A. D., D. Bashford, M. Bellott, R. L. Dunbrack, Jr., J. D. Evanseck, M. J. Field, S. Fischer, J. Gao, H. Guo, S. Ha, D. Joseph-McCarthy, L. Kuchnir, K. Kuczera, F. T. K. Lau, C. Mattos, S. Michnick, T. Ngo, D. T. Nguyen, B. Prodhom, W. E. Reiher III, B. Roux, M. Schlenkrich, J. C. Smith, R. Stote, J. Straub, M. Watanabe, J. Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera, D. Yin, and M. Karplus. 1998. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu, H., M. Elstner, and J. Hermans. 2002. Comparison of a QM/MM force field and molecular mechanics force fields in simulations of alanine and glycine “dipeptides” (Ace-Ala-Nme and Ace-Gly-Nme) in water in relation to the problem of modeling the unfolded peptide backbone in solution. Proteins. 50:451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahoney, M. W., and W. L. Jorgensen. 2000. A five-site model for liquid water and the reproduction of the density anomaly by rigid, nonpolarizable potential functions. J. Chem. Phys. 112:8910–8922. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillot, B. 2002. A reappraisal of what we have learnt during three decades of computer simulations on water. J. Mol. Liq. 101:219–260. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen, M. P., and D. J. Tildesley. 1987. Computer Simulation of Liquids. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

- 41.Essmann, U., L. Perera, M. L. Berkowitz, T. Darden, H. Lee, and L. G. Pedersen. 1995. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melchionna, S., G. Ciccotti, and B. L. Holian. 1993. Hoover NpT dynamics for systems varying in shape and size. Mol. Phys. 78:533–541. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melchionna, S. 2000. Constrained systems and statistical distribution. Phys. Rev. E. 61:6165–6170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martyna, G. J., M. E. Tuckerman, G. J. Tobias, and M. L. Klein. 1996. Explicit reversible integrators for extended systems dynamics. Mol. Phys. 87:1117–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stella, L., and S. Melchionna. 1998. Equilibration and sampling in molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys. 109:10115–10120. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voronoi, G. 1908. Research on primitive parallelograms. J. Reine Angew. Math. 134:198–287. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruocco, G., M. Sampoli, and R. Vallauri. 1992. Analysis of the network topology in liquid water and hydrogen sulphide by computer simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 96:6167–6176. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paci, E., and M. Marchi. 1996. Intrinsic compressibility and volume compression in solvated proteins by molecular dynamics simulation at high pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:11609–11614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richards, F. M. 1985. Calculation of molecular volumes and areas for structures of known geometry. Meth. Enzymol. 115:440–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loladze, V. V., D. N. Ermolenko, and G. I. Makhatadze. 2001. Heat capacity changes upon burial of polar and nonpolar groups in proteins. Protein Sci. 10:1343–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Despa, F., A. Fernández, and R. S. Berry. 2004. Dielectric modulation of biological water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93:228104-1–228104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elcock, A. H. 1998. The stability of salt-bridges at high temperatures: implications for hyperthermophilic proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 284:489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hernandez, G., F. E. Jr. Jenney, M. W. W. Adams, and D. M. LeMaster. 2000. Millisecond time scale conformational flexibility in a hyperthermophile protein at ambient temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:3166–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jaenicke, R. 2000. Do ultrastable proteins from hyperthermophiles have high or low conformational rigidity? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:2962–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fitter, J., and J. Heberle. 2000. Structural equilibrium fluctuations in mesophilic and thermophilic α-Amylase. Biophys. J. 79:1629–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lazaridis, T., I. Lee, and M. Karplus. 1997. · Dynamics and unfolding pathways of a hyperthermophilic and a mesophilic rubredoxin. Protein Sci. 6:2589–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colombo, G., and K. M. Merz, Jr. 1999. Stability and activity of mesophilic subtilisin E and its thermophilic homolog: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:6895–6903. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grottesi, A., M.-A. Ceruso, A. Colosimo, and A. Di Nola. 2002. Molecular dynamics study of a hyperthermophilic and a mesophilic rubredoxin. Proteins Struct. Funct. Gen. 46:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]