Abstract

To search for new indicators of self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), highly purified populations were isolated from adult mouse marrow, micromanipulated into a specially designed microscopic array, and cultured for 4 days in 300 ng/ml Steel factor, 20 ng/ml IL-11, and 1 ng/ml flt3-ligand. During this period, each cell and its progeny were imaged at 3-min intervals by using digital time-lapse photography. Individual clones were then harvested and assayed for HSCs in mice by using a 4-month multilineage repopulation endpoint (>1% contribution to lymphoid and myeloid lineages). In a first experiment, 6 of 14 initial cells (43%) and 17 of 61 clones (28%) had HSC activity, demonstrating that HSC self-renewal divisions had occurred in vitro. Characteristics associated with HSC activity included longer cell-cycle times and the absence of uropodia on a majority of cells within the clone during the final 12 h of culture. Combining these criteria maximized the distinction of clones with HSC activity from those without and identified a subset of 27 of the 61 clones. These 27 clones included all 17 clones that had HSC activity; a detection efficiency of 63% (2.26 times more frequently than in the original group). The utility of these characteristics for discriminating HSC-containing clones was confirmed in two independent experiments where all HSC-containing clones were identified at a similar 2- to 3-fold-greater efficiency. These studies illustrate the potential of this monitoring system to detect new features of proliferating HSCs that are predictive of self-renewal divisions.

Keywords: video microscopy, time-lapse imaging, cell-cycle kinetics, cell behavior, lineage tracking

Time-lapse video imaging offers unique opportunities to determine how specific physical properties of individual living cells change with respect to one another over time and under different conditions. Time-lapse micrography has been used for more than half a century (1–4) to study cell morphology during attachment and migration (5, 6), cell lifetimes (7, 8), growth (9), death (2, 10), contact inhibition (11), clonal heterogeneity (12), and mitosis (13). Software for extracting and analyzing cell lineage (14) and morphology (15) data from videos of cells also has an extensive history. Time-lapse studies of primitive hematopoietic cells have provided information about their cell membrane dynamics when cocultured with stromal cells (16, 17) or fibronectin (18), their kinetics of division (19), their morphology and migration (20), their localization in vivo (21), and their simultaneous expression of different fluorescent proteins (22).

Here, we asked whether time-lapse video imaging could be used to identify previously unidentified behavioral traits of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with functionally validated long-term multilineage repopulating activity in vivo. A number of groups have reported methods for obtaining highly purified (>20% pure) populations of HSCs from normal adult mouse bone marrow (23–28). One of these methods involves isolating cells lacking surface markers characteristic of mature blood cells (i.e., lineage marker-negative, or lin− cells) and able to efflux the fluorescent dyes, Rhodamine-123 (Rho− cells) and Hoechst 33342 (25). Efflux of Hoechst 33342 results in the appearance of a side population of cells (SP cells) in two-dimensional plots of fluorescent events (29). In mouse bone marrow (BM), the subset of lin−Rho−SP cells represents ≈0.004% of all of the cells. Assessment of the blood cells generated in mice after injection of single lin−Rho−SP cells has shown that 40% of these cells can produce all blood cell types for many (>4) months (25). Interestingly, most of the markers used to isolate HSC-enriched populations from steady-state mouse BM are not directly associated with HSC functional potential, because these phenotypes are altered when HSC are activated or stimulated to divide (30–34). In fact, very few stable properties of HSCs, apart from their defining developmental potential, have been identified. To search for previously unidentified properties of HSCs that remain relevant even while they are proliferating, we developed a microwell-array imaging system to visualize clones derived from individual HSCs over a 4-day period under conditions that support HSC self-renewal divisions (25, 35, 36). Each clone was then recovered and assayed for the presence of HSCs with long-term multilineage in vivo repopulating activity. Video images of these assayed clones were then used to correlate visible characteristics of the cultured cells with those that had produced functionally defined daughter HSCs.

Results

Cell-Division Kinetics of CD45midlin−Rho−SP Cells Determined by High-Resolution Video Tracking.

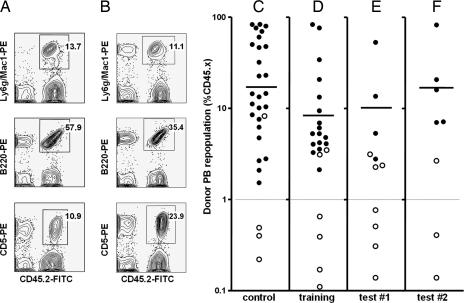

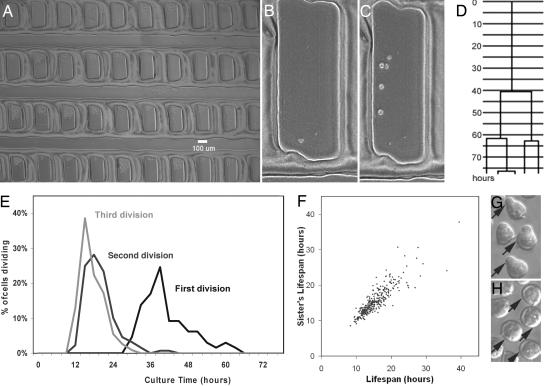

In vivo transplantation assays of 83 freshly isolated CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells showed that 31% of these were functionally detectable HSCs (Fig. 1A and C). Additional cells of this phenotype were shipped overnight from Vancouver, BC, to Waterloo, ON, and then 67 of these were loaded into the individual wells of three silicone microwell array chambers containing serum-free medium and 300 ng/ml murine Steel factor plus 20 ng/ml human IL-11 and 1 ng/ml human flt3 ligand. The arrays were incubated at 37°C for 4 days and imaged by using a ×5 objective at 3-min intervals throughout this period to allow the morphology and behavior of each cell and its progeny to be recorded and tracked (Fig. 2 B and C; and see Movies 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This sequence of images provided precise information about the timing of every cell division that occurred (n = 679) and, hence, the duration of each intervening cell cycle. From these data, we constructed pedigree diagrams for each of the 67 clones generated (Fig. 2D). The average times to the first, second, and third division determined for all cells that completed these cycles were 39.5 ± 7.6, 18.2 ± 5.2, and 15.8 ± 3.8 h, respectively (Fig. 2E). Sister cells (i.e., paired progeny derived from the same parental cell) divided with remarkable synchrony throughout the culture period (Fig. 2F). Transplantation data were obtained on 61 individually harvested clones, and the results showed that 17 of the 61 clones (28%) contained HSCs. This finding demonstrated that a high proportion of the input HSCs had executed at least one self-renewal division during imaging, despite the overnight transit of the cells before and after the 4-day culture period (Fig. 1 B and D).

Fig. 1.

In vivo repopulation characteristics of single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells or their clonal progeny. (A) Representative FACS profiles from a mouse repopulated with a single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cell. (B) Representative FACS profiles from a mouse repopulated with the in vitro progeny of a single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cell cultured for 4 days in an array chamber. (C) Proportion of peripheral blood (PB) leukocytes produced from a single freshly isolated CD45midlin−Rho−SP cell transplanted 16 weeks previously. Filled circles identify mice in which the level of donor-type leukocytes indicated that at least one HSC was present in the clone injected (>1% donor-type leukocytes at 16 weeks and >1% of both lymphoid and myeloid cells present at some point during the period the mice were serially monitored). Open circles represent mice in which some donor leukocytes could be detected at 16 weeks (>0.1%), but these were either <1% of the total and/or had not shown all lineages to have been included in the cells produced. Mice showing no (<0.1%) repopulation by donor-type cells are not shown. Horizontal bars show the geometric-mean size of the clones produced in vivo from the injected HSCs of HSC-containing clones. (D–F) Proportion of donor-type leukocytes seen in the PB of mice injected 16 weeks previously with a 4-day clone derived from a single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cell in the first imaging experiment (D) and in the second two experiments (E and F).

Fig. 2.

Description of the high-resolution time-lapse array system and representative culture results. (A) A digital image of an array showing 40 silicone microwells, each capable of holding up to ≈150 cells that can be tracked simultaneously. (B) Higher-power view of a representative well containing one CD45midlin−Rho−SP cell suspended in serum-free medium plus 300 ng/ml Steel factor, 20 ng/ml IL-11, and 1 ng/ml Flt-3 ligand. (C) Close-up of the well shown in B after 4 days at 37°C. (D) The pedigree diagram of the clone that developed in the well shown in C, illustrating the precision with which sequential cell divisions could be timed. (E) Cell-cycle time histogram of 67 individually cultured CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells. A delayed initial cell cycle was observed, followed by synchronously maintained subsequent divisions. Cells that did not complete the corresponding cell cycle were excluded from this histogram. (F) Comparison of the cell-cycle times of individual progeny pairs, demonstrating the pronounced synchrony retained between such “sister” cells, despite the wide range of cycle times observed. Cells whose sisters did not complete the corresponding cell cycle were not included in the plot. (G) Example of part of a clone in which many cells have large trailing projections (uropodia). Arrows indicate cells with uropodia. (H) Example of part of a clone in which very few cells have uropodia.

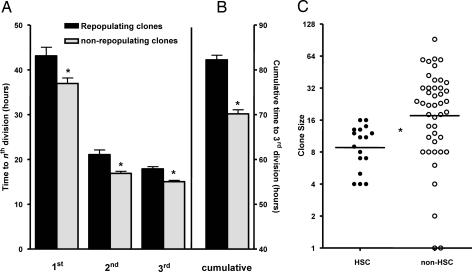

Association of Smaller Clone Sizes and Longer Cell-Cycle Times with Retention of HSC Activity.

Retrospective analysis showed that the 4-day clones containing HSCs were significantly smaller than those in which HSCs were not detected (log2 average size 8.8 ± 1.1 cells, n = 17 versus 17.6 ± 1.2 cells, n = 44, P < 0.005, Fig. 3C). This difference in clone size corresponds to an average difference of one fewer cell generation (3.1 versus 4.1) in the clones in which HSC self-renewal divisions were subsequently shown to have occurred. The average cell-cycle time of cells that completed one, two, and three divisions was also significantly longer for all three cycles (P < 0.005) in the HSC-containing clones as compared with those without detectable HSCs (Fig. 3A). The best discrimination between these two types of clones was obtained by combining all three cell-cycle times (Fig. 3B). Note that, for these calculations, we excluded clones in which three divisions or more did not occur, although there were only seven such clones in all. Interestingly, neither of the two starting cells that remained viable but did not divide during the 4-day imaging period displayed repopulating activity when subsequently injected into mice. Also, clones containing HSCs had significantly (P < 0.05, one-tailed t test) greater asymmetry between the cell-cycle times of the daughters of the clone founder than clones in which HSCs were not detected (for details, see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 3.

HSC activity is associated with smaller clone sizes and longer cell-cycle times. (A) Duration of the first, second, and third cell cycles was significantly longer in clones containing HSCs than in clones without HSCs. Cells that did not complete a first, second, or third cell cycle were excluded from this analysis. (B) The cumulative time to a third division of cells in HSC-containing clones was significantly longer than the corresponding value for clones without HSCs. Clones in which there were fewer than three cell divisions but the cells remained viable until the end of culture were assigned a time to third division equal to the total culture time. Error bars represent SEM, n = 67. (C) Comparison of 4-day clone size distributions for those that contained HSCs and those that did not. Horizontal bars indicate the geometric-mean values that are significantly different (P < 0.005). On average, clones with HSCs executed one fewer division over the 4 days than clones that did not contain HSCs.

Association of a Late Prevalence of Cells with Uropodia with Loss of HSC Activity.

We also looked for other features of cell behavior in clones that might be associated with their retention (or loss) of HSC activity, including the acquisition and loss of different types of cellular projections. During the first 14–18 h, only 6 of the 67 wells (≈9%) contained cells with lagging posterior projections (uropodia) although 45 (≈67%) contained cells with other cytoplasmic extensions. At later times, uropodia became more prevalent, particularly in some clones (Fig. 2 G and H). Filopodia (long, thin projections) were observed with high-resolution imaging (×20 and ×40 objectives) on most cells at the start and end of the period of monitoring, but these filopodia were not consistently visible in the lower-resolution images collected every 3 min (by using the ×5 objective) and were therefore not included in this analysis. When cells were scored for the presence or absence of uropodia during the final 12 h of the 4-day culture period, the majority of the cells in 25 of the clones (≈37%) contained uropodia. A significant association (P < 0.05) with the presence or absence of HSC activity was found only in the latter case, where none of the clones with a late predominance of cells with uropodia were found to contain HSCs.

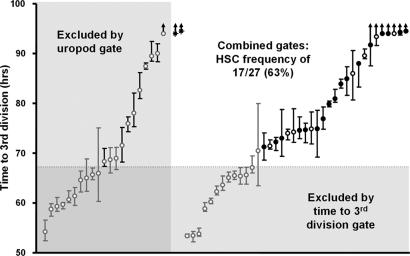

Identification of a Combination of Monitored Parameters That Are Predictive of HSC Self-Renewal Divisions.

We then asked whether combining two different parameters of cell behavior in the clones (time to third division and lack of uropodia on the 4th day of culture) would identify HSC-containing clones more efficiently than either of these parameters on its own. To apply the first parameter, we chose a minimal cell-cycle time that included all HSC-containing clones and excluded a maximum number of non-HSC-containing clones. To define such a cutoff in a way that could be applied to other data sets, we set it equal to the mean time to the third division measured on the entire data set minus 0.5 SD. For the data set shown in Fig. 3, this value was 67.23 h. This value was then used as a gate to subdivide clones into two groups; those clones in which the first cell to reach a third mitosis did so in <67.23 h and those in which the first cell to reach a third mitosis took longer than this threshold period (see Supporting Text and Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for additional details). We then further subdivided the clones into two groups based on whether or not the majority of the cells within the clone displayed uropodia at any point during the final 12 h of culture. Selection of clones in which the time to the third division was >67.23 h and ≤50% of the cells exhibited uropodia in the last 12 h of culture identified clones that contained HSCs at a 2.26-fold-higher frequency than in the original 61 clones analyzed (Fig. 4, Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Use of behavioral parameters defined by cell tracking to predict HSC-containing clones. Circles indicate the mean time to a third division in each clone. Bars indicate the ranges of these times. Arrows indicate that one or more of the cells did not complete a third division by the end of the culture period. Asterisks indicate wells in which the original cell had not yet divided at 96 h, when the cultures were terminated. Filled circles represent clones that contained a detectable HSC, and open circles represent clones that did not. Gray symbols represent clones that were excluded by one or both of the two criteria applied (i.e., the average time to a third division was <67.23 h and/or >50% of cells within the clone displayed uropodia during the final 12 h of culture). Filled symbols identify the 27 clones that were not excluded by either criteria (i.e., the fastest time to a third division was >67.23 h and ≤50% of cells within the clone displayed uropodia during the final 12 h of culture). The latter allowed the frequency of HSC-containing clones in the remainder to be increased from 28% to 63%, a 2.26-fold increase.

Table 1.

Application of selection criteria developed from the “training set” of data to results from two additional experiments

| Set | Fresh |

Cultured |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Nongated | Gate 1* | Gate 2† | Gates 1, 2 | |

| Training set | |||||

| No. of HSC-containing clones | 6 of 11 | 17 of 61 | 17 of 36 | 17 of 40 | 17 of 27 |

| Percentage | 55 | 28 | 47 | 43 | 63 |

| Fold enrichment | 1.00 | 1.69 | 1.53 | 2.26 | |

| Test set #1 | |||||

| No. of HSC-containing clones | 3 of 16 | 4 of 24 | 4 of 13 | 4 of 18 | 4 of 12 |

| Percentage | 19 | 17 | 31 | 22 | 33 |

| Fold enrichment | 1.00 | 1.85 | 1.33 | 2.00 | |

| Test set #2 | |||||

| No. of HSC-containing clones | 4 of 18 | 5 of 73 | 5 of 42 | 5 of 35 | 5 of 27 |

| Percentage | 24 | 6.8 | 12 | 14 | 19 |

| Fold enrichment | 1.00 | 1.74 | 2.09 | 2.72 | |

*Excluding clones containing one or more cells with a cumulative time to a third division faster than the mean minus 0.5 SD.

†Excluding clones containing >50% of cells with uropodia during the final 12 hours of culture.

The robustness of these criteria to identify HSC-containing clones was then tested by applying them to similar data acquired from two independently executed experiments of the same design. As in the first experiment, maintenance of HSC activity was evident in the clones analyzed after culturing single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells for 4 days (Fig. 1 E and F). Importantly, application of the same criteria identified in the first experiment to the data obtained from the two later experiments allowed the HSC-containing clones to again be predicted with a 2 to 3-fold-increased efficiency (Table 1).

Discussion

Here, we describe a time-lapse video monitoring system that allows high-resolution real-time tracking of cells in multiple expanding clones in vitro to be coupled with functional assays of the individually harvested clones at the end of the monitoring period. These unique features have made it possible to address questions about the biology of HSCs that have not been amenable to investigation. The objective of our study was to identify parameters that might be associated with HSC self-renewal divisions in vitro. From a survey of numerous cell features (see Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for details of other features considered), we identified two that each showed a significant association with clones containing HSCs after 4 days of culture: a prolonged cell-cycle time measured over thee divisions and a reduced proportion of progeny with uropodia at any time between 84 and 96 h of culture. In combination, these parameters identified all of the HSC-containing clones in each of the three experiments performed and consistently enhanced the identification of HSC-containing clones 2- to 3-fold independent of the starting purities of the HSCs tested (see controls in Table 1) or other interexperimental variations likely to have occurred, suggesting that these biomarkers are, indeed, robust features of mouse bone marrow HSCs.

These findings extend the results of previous studies that correlated longer cell-cycle times of primitive hematopoietic cells of both mouse (37) and human (38, 39) origin with the retention of their primitive cell properties. The experiments described here have taken this line of investigation a step further through the use of a more highly purified HSC starting population, a higher spatial–temporal-resolution monitoring system, and functional assessment of the HSC activity retained (or not) by each tracked clone. In this way, a link between HSC cell-cycle time and their self-maintenance in culture could be definitively established. Schroeder (40) has recently described a complementary computer-aided culture and time-lapse imaging system that he has used to describe the generation of HSC-derived clones on stromal cell feeder layers but without data for HSC activity in the clones produced. We anticipate that further use of both systems will provide valuable insights into how primitive hematopoietic cells interact with external cues to regulate their self-renewal and differentiation potential.

Multiple studies have associated a variety of cell projections with primitive hematopoietic cells (18, 21, 41–43). In particular, Frimberger et al. (16) observed several types of projections on the leading edge and periphery of cells in HSC-enriched populations using high-speed optical-sectioning microscopy and inverted fluorescent video microscopy. Giebel and colleagues (43) have described the appearance of uropodia at the rear pole of human CD34+ cells. Here, we found that the late presence of uropodia was negatively associated with retained HSC activity. Clearly, attention to the criteria used to define different categories of projections as well as the particular culture conditions used and the time in culture at which they are assessed will be important to future investigations of whether these projections play a role in HSC biology.

Although our approach is potentially applicable to any HSC-containing population, all candidate biomarkers would need to be screened again if a different isolation strategy were used, because the non-HSC component of such populations would likely be different. A strength of the approach used here is that it can be adapted to any source of HSCs or HSC isolation strategy because it makes no assumptions about the biological homogeneity of the cells being monitored. The most useful biomarkers are, however, those that can be directly linked to the defining developmental properties of HSCs. The technology and experimental design described here, thus, represent an important advance in the definitive identification of such features. In addition, the system we have described has the flexibility of allowing specific cells with tracked histories to be removed by micromanipulation at any time point and then assayed or analyzed. Cells containing reporter genes or labeled surface or internal components will further broaden the scope of cellular events that can be monitored. We, thus, anticipate increasing application of this powerful technology to many areas of cell biology.

Methods

Mice.

Bone marrow donors were 8- to 12-week-old C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 or -Ly5.2 mice. Transplant recipients were Ly5-congenic C57BL/6J-W41/W41 mice sublethally irradiated with 360-cGy x-rays at ≈350 cGy/min. Peripheral blood (PB) was collected at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplant, and the leukocytes were then stained with antibodies for donor and recipient CD45 allotypes plus lymphoid- and myeloid-specific markers. Long-term repopulation was defined as the detection of donor-derived leukocytes at >1% levels in the PB for at least 16 weeks. Multilineage repopulation was defined as the detection of >1% of both donor type lymphoid and myeloid cells at 4, 8, 12, and/or 16 weeks after transplantation. Evidence of both long-term and multilineage repopulation in the same recipient was used to infer that ≥1 HSC had been injected. For further details, see Supporting Text and Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Purification, Culture, and Shipment of CD45midlin−Rho−SP Cells.

Cell purification was performed as described in ref. 25, with minor modifications. See Supporting Text and Fig. 7, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for details. For controls, single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells were sorted into the individual wells of a round-bottom 96-well plate containing 100–200 μl of serum-free medium (SFM) (see Supporting Text), visually confirmed, and then injected individually directly into sublethally irradiated C57BL/6J-W41/W41 recipients. The, CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells to be imaged were sorted and collected into a 1.4-ml Eppendorf tube prefilled with SFM in Vancouver, BC, and then shipped via overnight courier (18–22 h) at 4°C to the University of Waterloo in Ontario. Upon arrival, the cells were warmed to 25°C, and 300 ng/ml murine Steel factor (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver), 20 ng/ml human IL-11 (Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA), and 1 ng/ml human Flt-3 ligand (Immunex, Seattle, WA) added to the medium. Single CD45midlin−Rho−SP cells were then micromanipulated into the individual microwells of an array chamber (Fig. 2A, prepared as described below), which was then placed at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere and imaged every 3 min by using phase contrast optics. The time of cytokine addition was set as 0 hours of culture time for all experiments. At the end of the 4 days of culture, the clones in the arrays were harvested individually, placed into separate 0.65-ml microcentrifuge tubes, and shipped via overnight courier at 4°C to Vancouver, where the cells in each tube were resuspended and injected into individual sublethally irradiated C57BL/6J-W41/W41 recipients.

Videotracking System.

Cells were cultured in custom-designed microwell chambers. Briefly, these microwell arrays were constructed by applying silicone gel to a glass coverslip to form a film ≈20 μm thick, and a 100-μm-wide glass scraper was then used to machine two sets of perpendicular rows to form the array wells before the gel set (Fig. 2A). A glass tube was then affixed around the array to form a reservoir to contain the culture medium. To deposit the cells within the array, the entire reservoir was filled with 1 ml of medium containing ≈50 cells that were then allowed to settle. Each of the 40 microwells was then loaded with a single cell by repositioning the settled cells using a glass micropipette guided by a 3-axis motorized micromanipulator. The micropipettes were made from capillary tubes (3-000-203-G/X; Drummond) by using a vertical pipette puller (Model 720; Kopf) and cut with a single-crystal diamond-tipped glass etcher to give an opening 15–30 μm wide. Images were obtained on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with phase-contrast optics and a Sony XCD-SX900 digital camera. Cells were exposed to light only during imaging. Each cell in each image of the ≈1850-image time courses was scored for morphological characteristics, location, and parentage by using human-assisted custom cell-tracking software that generated pedigree diagrams with other data superimposed on them for visualization. Data from these diagrams were then imported into standard analysis programs (excel, matlab, and prism) to test correlations between candidate biomarkers and HSC activity (details of the human-assisted tracking techniques and a list of candidate biomarkers that were tested are given in the Supporting Text and Table 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge gifts of reagents from StemCell Technologies, Genetics Institute, and Immunex; technical assistance from the Terry Fox Flow Cytometry Facility and staff of the Animal Resource Centre of the British Columbia Cancer Agency; and secretarial assistance from Adrienne Wanhill. This work was supported by grants from the Stem Cell Network (to C.E. and E.J.) and the National Cancer Institute of Canada (with funds from the Terry Fox Foundation) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HL-55435 (to C.E.). B.D. held a Stem Cell Network Studentship and a Terry Fox Foundation Research Studentship. D.K. held a Stem Cell Network Studentship and a Studentship funded jointly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Abbreviations

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- lin

lineage markers

- Rho

rhodamine 123

- SP

side population.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Schwobel W. Mikroskopie. 1952;7:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrek R., Ott J. N., Jr Am. Med. Assoc. Arch. Pathol. 1952;53:363–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramis N. J. J. Biol. Photogr. Assoc. 1956;24:27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siskin J. In: Cinemicrography Cell Biology. Rose G. G., editor. New York: Academic; 1963. pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen R. D., Zacharski L. R., Widirstky S. T., Rosenstein R., Zaitlin L. M., Burgess D. R. J. Cell Biol. 1979;83:126–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMilla P. A., Stone J. A., Quinn J. A., Albelda S. M., Lauffenburger D. A. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:729–737. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu T. C. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 1960;18:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Froese G. Exp. Cell Res. 1964;35:415–419. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(64)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zetterberg A., Killander D. Exp. Cell Res. 1965;39:22–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin G., Bender M. A. Exp. Cell Res. 1966;43:413–423. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(66)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martz E., Steinberg M. S. J. Cell Physiol. 1972;79:189–210. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040790205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Absher P. M., Absher R. G. Exp. Cell Res. 1976;103:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Concha M. L., Adams R. J. Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 1998;125:983–994. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sylwester D., Dennis S. M., Absher M. Comput. Biol. Med. 1980;10:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(80)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potel M. J., Sayre R. E., Robertson A. Comput. Biol. Med. 1979;9:237–256. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(79)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frimberger A. E., McAuliffe C. I., Werme K. A., Tuft R. A., Fogarty K. E., Benoit B. O., Dooner M. S., Quesenberry P. J. Br. J. Haematol. 2001;112:644–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner W., Saffrich R., Wirkner U., Eckstein V., Blake J., Ansorge A., Schwager C., Wein F., Miesala K., Ansorge W., Ho A. D. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1180–1191. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fruehauf S., Srbic K., Seggewiss R., Topaly J., Ho A. D. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Punzel M., Liu D., Zhang T., Eckstein V., Miesala K., Ho A. D. Exp. Hematol. 2003;31:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis K., Palsson B., Donahue J., Fong S., Carrier E. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:460–463. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki N., Ohneda O., Minegishi N., Nisikawa M., Ohta T., Takahashi S., Engel J. D., Yamamoto M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2202–2207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508928103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stadtfeld M., Varas F., Graf T. Methods Mol. Med. 2005;105:395–412. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-826-9:395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osawa M., Hanada K. I., Hamada H., Nakauchi H. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagers A. J., Sherwood R. I., Christensen J. L., Weissman I. L. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida N., Dykstra B., Lyons K. J., Leung F. Y. K., Eaves C. J. Exp. Hematol. 2003;31:1338–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benveniste P., Cantin C., Hyam D., Iscove N. N. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:708–713. doi: 10.1038/ni940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C.-Z., Li L., Li M., Lodish H. Immunity. 2003;19:525–533. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki Y., Kinjo K., Mulligan R. C., Okano H. Immunity. 2004;20:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodell M. A., Brose K., Paradis G., Conner A. S., Mulligan R. C. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato T., Laver J. H., Ogawa M. Blood. 1999;94:2548–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huygen S., Giet O., Artisien V., Di Stefano I., Beguin Y., Gothot A. Blood. 2002;100:2744–2752. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.8.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida N., Dykstra B., Lyons K., Leung F., Kristiansen M., Eaves C. Blood. 2004;103:4487–4495. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habibian H. K., Peters S. O., Hsieh C. C., Wuu J., Vergilis K., Grimaldi C. I., Reilly J., Carlson J. E., Frimberger A. E., Stewart F. M., Quesenberry P. J. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:393–398. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang C. C., Lodish H. F. Blood. 2005;105:4314–4320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller C. L., Eaves C. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13648–13653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Audet J., Miller C. L., Eaves C. J., Piret J. M. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002;80:393–404. doi: 10.1002/bit.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suda T., Suda J., Ogawa M. J. Cell Physiol. 1983;117:308–318. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041170305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brummendorf T. H., Dragowska W., Zijlmans J. M., Thornbury G., Lansdorp P. M. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:1117–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srour E. F., Tong X., Sung K. W., Plett P. A., Rice S., Daggy J., Yiannoutsos C. T., Abonour R., Orschell C. M. Blood. 2005;105:3109–3116. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schroeder T. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1044:201–209. doi: 10.1196/annals.1349.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frimberger A. E., Stering A. I., Quesenberry P. J. Blood. 2001;98:1012–1018. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner W., Ansorge A., Wirkner U., Eckstein V., Schwager C., Blake J., Miesala K., Selig J., Saffrich R., Ansorge W., Ho A. D. Blood. 2004;104:675–686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giebel B., Corbeil D., Beckmann J., Hohn J., Freund D., Giesen K., Fischer J., Kogler G., Wernet P. Blood. 2004;104:2332–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.