Abstract

Melatonin is involved in a variety of physiological functions through activating specific receptors coupled to GTP-binding protein. Melatonin and its receptors are abundant in the retina. Here we show for the first time that melatonin modulates glutamatergic synaptic transmission from cones to horizontal cells (HCs) in carp retina. Immunocytochemical data revealed the expression of the MT1 receptor on carp HCs. Whole-cell recordings further showed that melatonin of physiological concentrations potentiated glutamate-induced currents from isolated cone-driven HCs (H1 cells) in a dose-dependent manner, by increasing the efficacy and apparent affinity of the glutamate receptor. The effects of melatonin were reversed by luzindole, but not by K 185, indicating the involvement of the MT1 receptor. Like melatonin, methylene blue (MB), a guanylate cyclase inhibitor, also potentiated the glutamate currents, but internal infusion of cGMP suppressed them. The effects of melatonin were not observed in cGMP-filled and MB-incubated HCs. These results suggest that the melatonin effects may be mediated by decreasing the intracellular concentration of cGMP. Consistent with these observations, melatonin depolarized the membrane potential of H1 cells and reduced their light responses, which could also be blocked by luzindole. These effects of melatonin persisted in the presence of the antagonists of receptors for dopamine, GABA and glycine, indicating a direct action of melatonin on H1 cells. Such modulation by melatonin of glutamatergic transmission from cones to HCs is thought to be in part responsible for circadian changes in light responsiveness of cone HCs in teleost retina.

Melatonin (5-methoxy-N-acetyltryptamine), a primary hormone originally discovered in the pineal gland, has been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of a variety of physiological processes, such as circadian rhythm, reproduction, sleep, immune and vascular responses, etc. (see Brzezinski, 1997; and Vanecek, 1998 for reviews). The melatonin receptors, mediating the actions of melatonin, are now classified into MT1 (Mel1a), MT2 (Mel1b) and MT3 (ML2) subtypes. While MT1 and MT2 receptor subtypes have been cloned from different species and shown to be G-protein coupled (Reppert et al. 1994, 1995), it is still uncertain whether the MT3 receptor matches all the criteria for classifying as a G-protein-coupled receptor (Dubocovich et al. 2003).

In the vertebrate retina, melatonin is produced by photoreceptors, and the synthesis and release of melatonin show a marked daily variation, being at higher levels at night and at lower levels during the daytime (Besharse & Iuvone, 1983; Tosini & Fukuhara, 2003). Melatonin concentration in the retina and its circadian changes have been determined in various species (Cahill, 1996; Alonso-Gomez et al. 2000; Tosini, 2000; Zawilska et al. 2003). Moreover, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemical studies have demonstrated the presence of melatonin receptors in the retina of various species (Reppert et al. 1995; Fujieda et al. 1999; Savaskan et al. 2002; Scher et al. 2002; Wiechmann, 2003; Wiechmann et al. 2004; Sallinen et al. 2005). Melatonin is implicated in many retinal functions, including retinomotor responses, rod disc shedding, and regulation of horizontal cell (HC) light responsiveness, dopamine release, etc. (see Vanecek, 1998 for review). It was recently shown in the fish retina that activation of melatonin receptors could regulate the activity of cone-driven HCs, an activity which is thought to be mediated by modulating dopamine release from interplexiform and amacrine cells (Ribelayga et al. 2004). Melatonin could also modulate receptors for other neurotransmitters expressed on retinal neurones. In cultured chick retinal neurones, melatonin receptors are coupled to adenylate cyclase, which is regulated by D1 dopamine receptors (Iuvone & Gan, 1995), reflecting a direct functional interaction of these two types of receptor. Modulation by melatonin of neurotransmitter–receptor systems in the retina, however, is not necessarily mediated by melatonin receptors. For instance, in isolated carp bipolar and amacrine-like cells, melatonin accelerates desensitization of GABAA receptor-mediated currents, which may be due to the allosteric action of melatonin bound to a site of the GABAA receptor (Li et al. 2001).

In the present work we show that the MT1 receptor is expressed on HCs in carp retina by using immunocytochemistry. We further present data showing, for the first time that melatonin potentiates glutamate-receptor-mediated currents recorded from isolated carp H1 cells via the activation of the MT1 receptor, which may be in part responsible for melatonin-caused reduction of the light responses of these cells. These results suggest that melatonin may probably play an important role in the circadian regulation by melatonin of light responsiveness of cone HCs via directly modifying the activity of glutamate receptors on these cells.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on the adult crucian carp (Carassius carassius) retina. The animal, maintained under 12 h: 12 h light:dark cycle for at least 1 week, was dark-adapted for 20 min prior to an experiment and then deeply anaesthetized with 0.01% tricaine methylsulphonate, before being decapitated and pithed. The eyeball was enucleated and hemisected under dim red light. Adequate care was taken to minimize pain and discomfort to animals in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal experimentation.

Immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis

Procedures for immunocytochemical double-labelling analysis were basically similar to those used in a previous work, with minor modifications (Xu et al. 2003). In brief, isolated carp retinas were immersion-fixed in fresh 4% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4) for 10 min at 4°C and then sequentially cryoprotected at 4°C in 10, 20 and 30% (w/v) sucrose in 0.1 m PBS for 2 h, 2 h, and overnight, respectively. They were embedded in OCT (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN, USA) and frozen by liquid nitrogen. Vertical sections were made at 14 µm thickness on a freezing microtome (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and collected on gelatin chromium-coated slides. Indirect immunofluorescence labelling was performed for the preparations. The sections were blocked and permeabilized with 6% normal donkey serum, 1% normal bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with the primary antibodies goat polyclonal antibody against the MT1 receptor (sc-13186; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) and mouse monoclonal antibody against GAD67 (MAS5406; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA), at working dilutions of 1: 500 and 1: 1000, respectively. The secondary antibodies Texas-red-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), diluted to 1: 200, were used to reveal the binding sites. The sections were incubated sequentially in the primary antibodies and secondary antibody at 4°C for 3 days and 2 h, respectively. Washed with PBS and coverslipped, fluorescently labelled sections were imaged with a Leica SP2 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany) using a ×63 oil-immersion objective lens. Single optical sections were made through the preparation at intervals of 1.0 μm.

Western blot analysis was conducted following the procedure previously described in detail (Zhao & Yang, 2001). The extract samples (2.0 mg ml−1, 20 μl) were loaded, subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes using the Mini-PROTEAN 3 Electrophoresis System and the Mini Trans-Blot Electrophoretic Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked with non-fat milk at room temperature for 2 h, and then incubated with the antibody against the MT1 receptor, at a working dilution of 1: 1000, overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed, incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated donkey antigoat IgG (1: 5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) for 2 h at 4°C, and finally visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Height, IL, USA).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

HCs were acutely dissociated from retinas by enzymatic and mechanical treatments, as previously described (Lu et al. 1998). Chopped retina pieces were incubated in Hanks' solution with 60 U ml−1 papain (Caliochem-Novabiochem Corp., CA, USA) and 1 mg ml−1 cysteine for 30 min at 25°C. Hanks' solution contained (mm): NaCl 137, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1, sodium pyruvate 1, NaH2PO4 1, NaHCO3 0.5, Hepes 20 and glucose 16, pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH. After rinsing with fresh Hanks' solution, the papain-treated retina pieces were kept in normal Hanks' solution for up to 8 h at 4°C. Cells were freshly dissociated from the stored retina pieces by gentle trituration with fire-polished Pasteur pipettes, and the cell suspension was placed onto a plastic dish mounted on the stage of a phase-contrast microscope (IX70; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). Cells were bathed in Ringer solution containing (mm) NaCl 145, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, Hepes 10 and glucose 16, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. HCs were easily identified by their typical morphology and by the characteristic inwardly rectifying K+ current (Lasater, 1986; Lu et al. 1998). Whole-cell membrane currents of HCs, voltage-clamped at −60 mV, were recorded with pipettes of 5–7 MΩ resistance, when filled with a solution containing (mm) KCl 60, KF 50, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, EGTA 10, Hepes 10, ATP 4 and GTP 0.5, pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH, connected to an EPC9/2 patch-clamp amplifier (Heka, Germany). The liquid junction potential was compensated on-line. Fast capacitance and cell capacitance were cancelled by the circuit of the amplifier. Seventy per cent of the series resistance of the recording electrode was compensated. Analog signals were filtered at 2 kHz, sampled at 10 kHz, and stored on PC hard disk for further off-line analysis. Desensitization of the response to glutamate was fitted to a monoexponential equation: I(t) =A × exp(−t/τ) +C, where A is the peak current, t is time, τ is the time constant, and C is an offset. Dose–response relationships of glutamate-induced currents were fitted to the equation: I/Imax= 1/(1 + (EC50/[Glu])n), where I is the current response elicited by a given glutamate concentration [Glu], Imax is the response at a saturating concentration of glutamate, EC50 is the concentration of glutamate producing a half-maximal response, and n is the Hill coefficient. The normalized percentage potentiation of melatonin was calculated by the equation: (Imelatonin−Icontrol)/Icontrol× 100%. The data were all presented as means ± s.e.m. Student's paired t test was performed for statistical analysis.

All solutions were delivered using a stepper motor-based rapid solution changer RSC-100 (Bio-Logic Science Instruments, France), as described in detail previously (Lu et al. 1998). The recorded cells were lifted from the dish bottom, and completely bathed in the solution. The solution exchange could be completed in a few milliseconds (Lu et al. 1998).

Intracellular recording and photostimulation

Intracellular recordings were made from HCs in the isolated, superfused flat-mounted retina (Huang et al. 2004) during the daytime. The retina, superfused with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Ringer solution, consisting of (mm) NaCl 116, KCl 2.4, CaCl2 1.2, MgCl2 1.2, NaHCO3 30, and glucose 10, buffered to pH 7.7, was illuminated diffusely from the photoreceptor side by a dual-beam photostimulator, which provided two coincident 8 mm-diameter spots around the electrode tip. Light intensities and wavelengths of the two beams were changed by calibrated neutral density and interference filters. All light intensities referred to in the text are in log units relative to the maximum intensity (logI= 0), which was 5.5 × 1013 quanta cm−2 s−1. Glass microelectrodes filled with 4 m potassium acetate and having a tip resistance of 70–150 MΩ, in combination with an amplifier (MEZ 8300; Nihon Koden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), were employed to record intracellular potentials. Cone- and rod-driven HCs were identified by reference to previously well-established criteria (cone HCs: Yang et al. 1982, 1983, 1994; Xu et al. 2001; rod HCs: Kaneko & Yamada, 1972; Yang et al. 1988, 1994).

Chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise specified, and most of them were freshly dissolved in Ringer solution. Melatonin, luzindole and K 185 were first dissolved in DMSO and then added to Ringer solution on the day of experiment. The final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.1% which had no effects on the glutamate-induced currents from isolated HCs, or on the membrane potential and light responses of these cells intracellularly recorded from the isolated, superfused retina.

Results

MT1 receptors were expressed in HCs

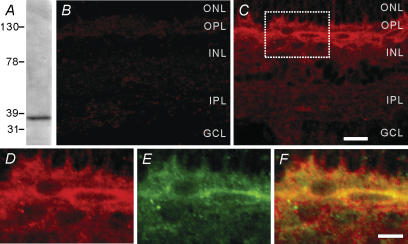

The specificity of the MT1 receptor antibody was first tested using Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 1A, the antibody revealed a single immunoreactive band at approximately 37 kDa, which precisely corresponds to the predicted molecular mass of the receptor (Song et al. 1997). The specificity of the immunofluorescence labelling was then evaluated by omitting one or both of the two primary antibodies during the incubation. When one of the primary antibodies was omitted, only the immunoreactivity for the remaining antibody was revealed, and omission of the both eliminated any immunolabelling. It was further found that no cross-reactivity of species-specific secondary antibodies was observed when the retina preparation was stained by a mixture of the two secondary antibodies after incubation with one of the two primary antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1B, almost no immunoflorescence labelling could be found when the MT1 antibody was pre-absorbed with the immunizing antigen, indicating that the protein recognized by the rabbit anti-MT1 antiserum used in this work may most likely be the MT1 receptor. Figure 1C–F shows confocal laser scanning micrographs of the vertical sections of the carp retina double-labelled with the antibodies against the MT1 receptor and GAD67, a marker of GABAergic neurones. In the low-power micrograph (Fig. 1C), the MT1 immunoreactivity was diffusely distributed in the neural retina, with the labelling being rather strong in the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and the distal part of the inner nuclear layer (INL). The region of OPL and outer INL marked by the box is shown at higher magnification in Fig. 1D–F. From the merged image (Fig. 1F) of Fig. 1D, showing MT1 immunoreactivity, and Fig. 1E, showing GAD and MT1 immunoreactivity, it was clear that the somata of the HCs were strongly MT1 immunoreactive and the labelling delineated the cells, suggesting that the MT1 receptor may be predominantly expressed on the cell membrane. Processes of these HCs located in the OPL were also MT1 immunoreactive, though they could not be clearly distinguished.

Figure 1. Immunolabelling of carp horizontal cells with the anti-MT1 receptor antibody.

A, Western blot of whole carp retina extract using the antibody revealed a single band of approximately 37 kDa at the corresponding molecular mass. B, confocal micrograph of a vertical cryostat section of the carp retina for which the MT1 receptor antibody was pre-absorbed with the immunizing antigen. Almost no immunofluorescence labelling was found, indicating that the protein recognized by the rabbit anti-MT1 antiserum used in this work may most likely be the MT1 receptor. C, confocal micrograph of a vertical section of the carp retina labelled with the MT1 antibody, showing that MT1 immunoreactivity was diffusely distributed in the neural retina. Note that the labelling was strong in the OPL and the distal part of the INL. The region of the OPL and outer INL marked by the box is shown at a higher magnification (D–F). D, micrograph of the marked region, showing MT1 immunoreactivity. E, micrograph of the same region labelled with the antibody against GAD67, a marker of GABAergic horizontal cells (HCs). F, merged images of D and E. Double-labelled elements appear yellowish. Somata and processes of the GAD67-positive HCs were clearly MT1 immunoreactive. Note that the labelling depicts the cell contours, suggesting the expression of the MT1 receptor on the cell membrane. All the micrographs were obtained by signal optical sectioning at intervals of 1.0 μm. ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 20 μm for B and C; 10 μm for D–F.

Melatonin potentiates glutamate-induced currents from isolated cone HCs

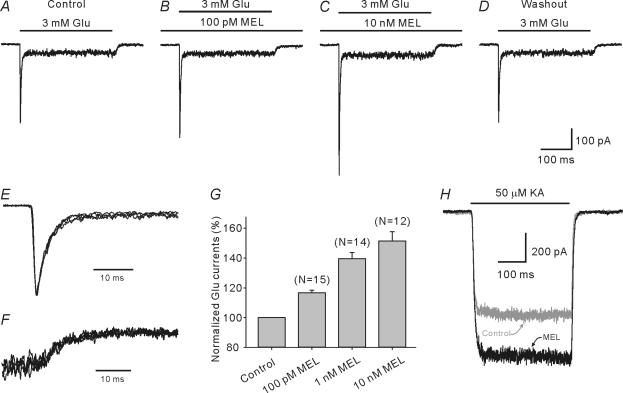

Carp retinal HCs exclusively express the AMPA-preferring glutamate receptor subtype (Lu et al. 1998). We first examined if and how melatonin modulates AMPA receptor-mediated currents of HCs. The experiments were mainly performed on H1 cells, which have a relatively small soma (10–20 μm in diameter) and limited process size. H1 cells, together with H2 and H3 cells, are known to be cone driven (Dowling, 1987). Some experiments were also done on H2 and H3 cells and no significant difference could be found in regard to melatonin modulation of glutamate-induced currents. Melatonin at concentrations ranging between 100 pm and 500 μm alone failed to induce any detectable current from H1 cells (data not shown). Figure 2A–D shows the effects of melatonin of increasing concentrations on the glutamate-induced current recorded from an H1 cell. The inward current response of the cell to 3 mm glutamate, a concentration that is little higher than the EC50 (1.08 mm) (Lu et al. 1998), recorded in normal Ringer solution, reached a peak in less than 2 ms, and then rapidly decayed to a much lower steady level (desensitization) with a time constant of 3.6 ms (Fig. 2A), which is typical of the AMPA receptor-mediated response (Lu et al. 1998). When the cell was incubated with 100 pm melatonin, both peak and steady-state currents of the response were gradually increased in size with time. The peak current was increased from the control level (381 pA) to a steady level of 448 pA in 2 min, whereas the steady-state current was increased from 39 to 45 pA (Fig. 2B). When the concentration of melatonin was increased to 10 nm, the peak and steady-state currents were further increased to 627 and 54 pA, respectively (Fig. 2C). Full recovery of the current response to the control level could be obtained after washout with Ringer solution for 3 min (Fig. 2D). This potentiation by melatonin of the glutamate current was seen in 58 out of 75 H1 cells tested. For the remaining 17 cells, glutamate current responses were almost unchanged by melatonin. It was noteworthy that the rise time and the desensitization course were hardly altered, while the peak amplitude was significantly potentiated. In Fig. 2E, the activation and desensitization courses of the responses shown in Fig. 2B and C were normalized and then superimposed on the control response at a much faster time scale. It was evident that these normalized responses precisely coincide with the control response. The 10–90% rise time of the control responses was 1.54 ± 0.16 ms, whereas that of the current responses obtained in the presence of 10 nm melatonin was 1.49 ± 0.20 ms (n = 12, P > 0.05). Meanwhile, the rate of desensitization of control responses (τ= 3.82 ± 0.47 ms) also remained unchanged in the presence of 10 nm melatonin (3.63 ± 0.41 ms, P > 0.05). The results obtained following the incubation of 100 pm melatonin were similar. To test if deactivation was affected by melatonin, the deactivation courses of the responses shown in Fig. 2B and C were normalized and compared at a much faster time scale by enlarging and superimposing them (Fig. 2F). It is clear that all these three traces coincide precisely.

Figure 2. Potentiation by melatonin of glutamate-induced currents from H1 cells.

A, control current response of an H1 cell to 3 mm glutamate (Glu) in normal Ringer solution; the response was characterized by fast desensitization. B and C, both peak and steady-state currents of the response of the cell were dose-dependently potentiated by incubation with melatonin (MEL) at 100 pm (B) and 10 nm (C). D, the response of the cell was obtained after washout with normal Ringer solution for 4 min. The cell was voltage clamped at −60 mV. E, activation and desensitization courses of the responses shown in B and C, when normalized, are superimposed on the control response at a much faster time scale. The two normalized traces coincide with the control trace, indicating that the receptor desensitization was unaffected by melatonin. F, deactivation courses of the responses shown in B and C, when normalized, are superimposed on the control response at a much faster time scale. The two normalized traces precisely coincide with the control trace, indicating that the receptor deactivation was unaffected by melatonin. G, relative potentiation of glutamate peak currents of H1 cells as a function of melatonin concentration. Data obtained from each cell at different concentrations of melatonin were normalized to the current of that cell recorded in normal Ringer solution and then averaged. Values in the parentheses above the bars indicate the number of cells tested for each dose. H, effects of melatonin on kainic acid (KA)-induced current from an H1 cell. The sustained current induced by 50 μm KA (grey trace, control) was significantly potentiated by 10 nm melatonin (dark trace, MEL).

We further determined the dose dependency of the melatonin-induced potentiation of the glutamate response more quantitatively in cells for which the potentiation was observed. For all these cells the current responses to 3 mm glutamate repetitively applied at intervals of 1 min changed in peak amplitudes by less than 10%. The effect of melatonin on the current response amplitude was determined for between one and three concentrations, depending on the cell, and relative potentiation was calculated for each cell. As shown in Fig. 2G, the peak of the glutamate responses was increased by 16.6 ± 1.9% (P < 0.001, n = 15) with incubation of 100 pm melatonin. Furthermore, incubation with melatonin of 1 nm and 10 nm potentiated the peak response by 39.5 ± 4.0% (P < 0.001, n = 14) and 51.2 ± 6.3% (P < 0.001, n = 12), respectively. Meanwhile, the steady-state currents were also dose dependently potentiated by melatonin (14.9 ± 4.3% for 100 pm, 31.5 ± 8.7% for 1 nm, and 43.5 ± 9.9% for 10 nm).

We also investigated the effects of melatonin on kainic acid (KA)-induced currents, which are sustained and do not show any desensitization (Lu et al. 1998). As shown in Fig. 2H, melatonin of 10 nm increased the current of the H1 cell from 704 to 989 pA. Similar results were obtained in four other H1 cells. The relative increase of the response amplitude was 26.8 ± 8.2% (P < 0.05, n = 5).

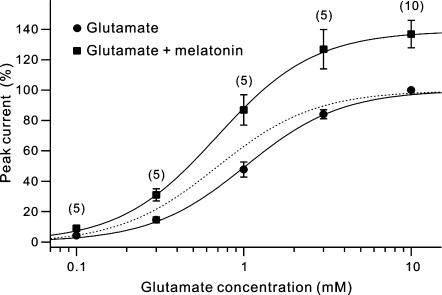

Melatonin increases both receptor efficacy and affinity for glutamate

We further determined the dose–response relationships of the glutamate-induced currents of H1 cells in the absence and presence of 10 nm melatonin to explore whether melatonin may change the affinity and efficacy of AMPA receptors of H1 cells for glutamate. For each of the cells tested, we recorded the responses to three concentrations of glutamate, first recorded in Ringer solution and then in the presence of melatonin. Relative potentiation was calculated for each of the doses. When the average dose–response relationship (Fig. 3, squares) based on the data pooled from between five and ten H1 cells obtained in the presence of 10 nm melatonin was compared to that determined in normal Ringer solution (circles), it was clear that the responses to glutamate of different concentrations, ranging from 0.1 mm to 10 mm (a saturating concentration that induced maximal current), were all potentiated to different extents. The Imax to 10 mm glutamate, was increased to 137.0% of the control level (P < 0.01), suggesting an increase in efficacy of glutamate. When the dose–response relationship obtained in the presence of 10 nm melatonin was further normalized by the amplitude of the maximal peak response to that obtained in normal Ringer solution, it was found that the curve obtained with 10 nm melatonin, as a whole, was shifted to the left along the abscissa, and the EC50 was reduced from 1.03 ± 0.04 mm (control) to 0.69 ± 0.02 mm, indicating an increased apparent affinity of glutamate receptors. It was noteworthy that the Hill coefficient was not significantly changed (1.52 ± 0.07 versus 1.49 ± 0.03, P > 0.05).

Figure 3. Melatonin increases receptor efficacy and affinity for glutamate in H1 cells.

Dose–response relationships for peak currents of H1 cells induced by glutamate in Ringer solution and in the presence of melatonin are represented by ▪ and •, respectively. For each cell, responses to three concentrations of glutamate were first recorded in Ringer solution and then in the presence of 10 nm melatonin. The response peaks obtained at different concentrations of glutamate were normalized to that of the response to 10 mm, a saturating concentration, of glutamate for each cell in the absence of melatonin. Curve fitting was performed for the averaged data, yielding EC50 values of 1.03 0.04 and 0.69 ± 0.02 mm in the absence and presence of 10 nm melatonin, respectively. The dashed curve is the normalized dose–response relationship in the presence of 10 nm melatonin, by that in normal Ringer solution, clearly demonstrating that the curve was shifted leftward by melatonin. Values in parentheses indicate the number of cells tested for each dose.

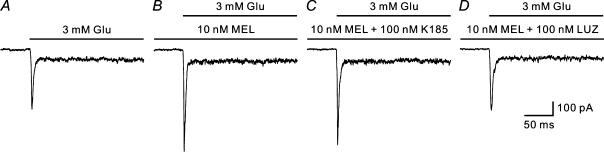

Luzindole, but not K 185, blocks melatonin-induced potentiation of glutamate currents

We further examined how K 185, a specific antagonist of the MT2 receptor (Sugden et al. 1999; Faust et al. 2000) and luzindole, a competitive antagonist of both MT1 and MT2 receptors (Browning et al. 2000), may alter the effects of melatonin on the glutamate currents of H1 cells. Figure 4 shows the results of such an experiment obtained in an H1 cell. Similar to that shown in Fig. 2B, 10 nm melatonin significantly potentiated the peak current in response to 3 mm glutamate (Fig. 4B). When 10 nm melatonin was substituted by a mixture of 100 nm K 185 and 10 nm melatonin, the potentiated glutamate response was nearly unchanged (Fig. 4C). The cell was then washed out with normal Ringer solution for 3 min and the current recovered to the control level. With incubation of a mixture of 100 nm luzindole and 10 nm melatonin for another 2 min, however, the response was almost identical to the control response and no potentiation was observed at all (Fig. 4D), with a relative change of 99.1 ± 2.3% (P > 0.05, n = 6).

Figure 4. Melatonin-caused potentiation of glutamate currents is blocked by luzindole, but not K 185.

The response to 3 mm glutamate (A) recorded from an H1 cell was potentiated by 10 nm melatonin (B). C, in the presence of 100 nm K 185, a specific MT2 receptor antagonist, 10 nm melatonin persisted to potentiate the current response. D, in the presence of 100 nm luzindole (LUZ), a MT1/MT2 receptor antagonist, the current response was no longer potentiated by melatonin. All the responses were recorded from the same H1 cell, which was voltage clamped at −60 mV.

Melatonin-induced potentiation of glutamate responses may be mediated by a decrease in intracellular cGMP concentration

It is well documented that melatonin receptors are coupled to G-protein and activation of these receptors may regulate several second messengers, among which cAMP and cGMP may be major ones (Vanecek, 1998). We therefore tested the effects of intracellular administrated cAMP and cGMP by adding these chemicals in the pipettes.

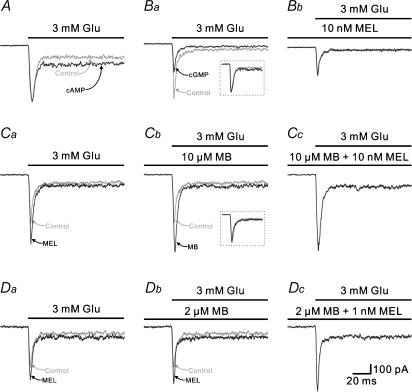

Figure 5A shows that internal infusion with 1 mm cAMP for 5 min did not change the peak amplitude of the response to 3 mm glutamate recorded in an H1 cell, but considerably potentiated the steady-state current, an effect that was quite different from the melatonin effect. In all seven cells tested, the steady-state current was increased by 71.3 ± 21.5% in the presence of 1 mm cAMP, while there was no significant change in peak amplitudes (102.4 ± 3.1% of control, P > 0.05). Internal infusion with 1 mm cGMP, however, clearly reduced the peak amplitude of the response. In the example shown in Fig. 5Ba, the peak amplitude of the response was 535 pA when sealing was just made (grey trace), but it gradually decreased in size and reached a steady level of 281 pA in 4 min (dark trace). Meanwhile, the steady-state current was also reduced in size from 51 to 28 pA. This effect of cGMP was reminiscent of the melatonin effect. It was of interest that the whole-current trace, when normalized, coincides with the control trace (see the inset). In five cells tested, internal infusion with 1 mm cGMP reduced the peak current amplitude to 48.4 ± 5.6% and the steady-state current to 54.3 ± 9.8% of the control levels (P < 0.001), respectively. Furthermore, when 10 nm melatonin was applied to the cGMP-filled cell, the glutamate current remained unchanged (100.5 ± 2.2%, n = 5, P > 0.05) (Fig. 5Bb). We also investigated the effects of methylene blue (MB), a guanosine cyclase inhibitor that decreases the intracellular concentration of cGMP, on the glutamate currents. As shown in Fig. 5Ca, melatonin of 10 nm potentiated the glutamate peak and steady-state currents of the H1 cell from 503 and 95 pA (control, grey trace) to 721 and 113 pA (MEL, dark trace), respectively. With incubation of 10 μm MB, the control glutamate peak and steady-state currents were also increased in size and reached a steady level of 802 and 122 pA (dark trace) in 5 min (Fig. 5Cb), but the desensitization kinetics was almost unchanged (τ= 3.5 ± 0.2 versus 3.5 ± 0.3 ms, n = 5, P > 0.05), as evidenced by the fact that the current response obtained in the presence of MB, when normalized, precisely coincides with the control response (see the inset), thus mimicking the effects of melatonin. In five cells tested, the peak and steady-state currents obtained with 10 μm MB were increased by 45.9 ± 6.1 and 38.3 ± 5.4%, respectively. ODQ, another guanosine cyclase inhibitor, had the effect similar to that of MB (n = 5, data not shown). It was further found that the glutamate currents of this cell remained unchanged when 10 nm melatonin was co-applied with 10 μm MB (Fig. 5Cc). The data obtained in all five cells tested indicated that peak current amplitudes obtained with a mixture of 10 μm MB and 10 nm melatonin were not significantly changed from those obtained with 10 μm MB alone (99.8 ± 1.9% of control, n = 5, P > 0.05). These results suggest that the potentiation by MB and melatonin of the glutamate current may be via the same pathway. We further examined if the effects of melatonin and MB may be additive when their concentrations were lower. Figure 5Da shows that melatonin of 1 nm potentiated the peak glutamate current of the H1 cell from 425 pA (control, grey trace) to 561 pA (MEL, dark trace). With incubation of 2 μm MB, the peak current was increased to 595 pA in 5 min (Fig. 5Db). When 1 nm melatonin was co-applied with 2 μm MB (Fig. 5Dc), the current was increased to 675 pA, a level significantly higher than that caused by either melatonin or MB. Similar results were obtained in four other H1 cell. Melatonin of 1 nm potentiated the glutamate currents by 30.1 ± 5.9%, whereas 2 μm MB potentiated those by 36.1 ± 5.8%. While both melatonin and MB were co-applied a larger (47.4 ± 9.2%) potentiation of glutamate currents was found.

Figure 5. Melatonin-caused potentiation of glutamate-induced currents may be mediated by cGMP.

A, internal infusion with 1 mm cAMP did not change the glutamate-induced current recorded from an H1 cell. The grey trace (control) is the response to 3 mm glutamate recorded when sealing was just made, with a pipette containing 1 mm cAMP, whereas the dark trace was obtained in 5 min. Changes in intracellular cAMP did not affect the peak response, but potentiated the steady-state current. B, internal infusion with 1 mm cGMP reduced the glutamate-induced current from an H1 cell. The grey trace (control) in Ba is the response to 3 mm glutamate recorded when sealing was just made, with a pipette containing 1 mm cGMP, whereas the dark trace in Ba was obtained in 5 min (cGMP). In the inset, the dark trace, when normalized, is superimposed on the grey trace; the two traces coincide very well. When 10 nm melatonin was then applied to the cell, the glutamate current remained unchanged (Bb). C, effect of methylene blue (MB) on the glutamate current of an H1 cell. Ca, the response to 3 mm glutamate (grey trace, control) was potentiated by 10 nm melatonin (dark trace, MEL). Cb, like melatonin, 10 μm MB potentiated the current response to 3 mm glutamate, but did not change the desensitization course. The grey trace and dark trace are the control response and the 10 μm MB-potentiated response, respectively. When normalized, the two traces coincide (inset). Cc, the current response recorded in the presence of 10 μm MB was no longer potentiated by 10 nm melatonin. D, either 1 nm melatonin (Da) or 2 μm MB (Db) potentiated the current response to 3 mm glutamate of an H1 cell. The potentiated current response by adding a mixture of 2 μm MB and 1 nm melatonin was significantly larger in size than the potentiated response obtained when either 1 nm melatonin or 2 μm MB was applied alone to the cell (Dc), indicating that the effects of melatonin and MB were additive. Recordings shown in A, B, C and D were obtained in four different H1 cells.

Melatonin modulates light responses of cone HCs

To explore physiological implication of the melatonin-induced potentiation of the glutamate response, we investigated effects of melatonin on light responses of cone HCs intracellularly recorded in the isolated, superfused retina.

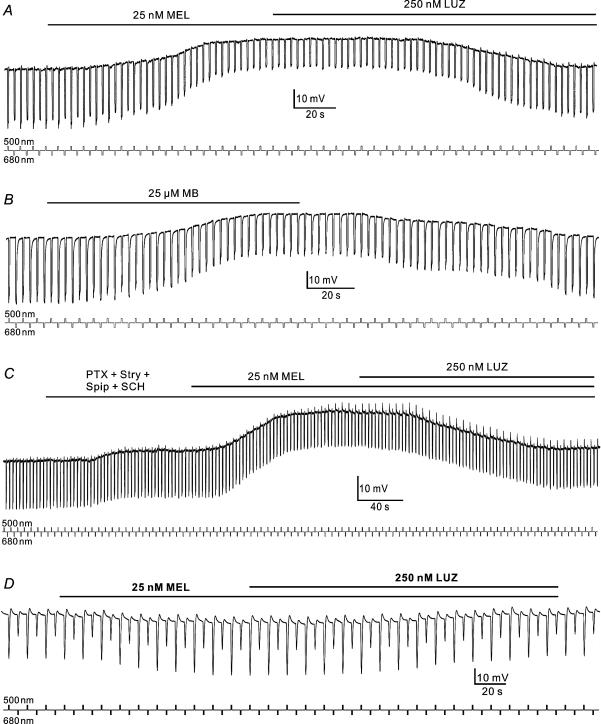

After a preparation was set up in the perfusion chamber, light flashes of 500 nm (logI=−0.6) and 680 nm (logI=−0.6) were alternately presented at 1 Hz for about 5 min to release the cone system from the dark suppression (Xu et al. 2001). During the experiments, these two light flashes were alternately presented at intervals of 3 s, which is a routine experimental protocol in this laboratory that has been demonstrated to completely suppress the carp rod-driven light responses (Huang et al. 2004). Figure 6A illustrates the results obtained in a H1 cell. The light responses of this cell to test flashes of 500 nm (log I=−0.6) and 680 nm (log I=−0.6), predominantly activating short-wavelength sensitive cones, most probably green-sensitive (G) cones, and red-sensitive (R) cones, respectively (Yang et al. 1982, 1983, 1994), were of comparable amplitudes, but they exhibited different waveforms, suggesting that these responses were indeed driven by inputs from different types of cones. Application of 25 nm melatonin depolarized the H1 cell from −28 to −10 mV in 2 min. In association with the membrane depolarization, the light responses to both test flashes were reduced in amplitudes to the same extent (around 50% of the control responses). Co-application of 250 nm luzindole blocked the melatonin effects, and both membrane potential and light responses returned to the original levels obtained before the application of melatonin. Such results were consistently obtained in six other H1 cells. On average, the membrane potential of the cells was depolarized by 14.1 ± 2.1 mV, whereas the relative decrease of the amplitude was 46.7 ± 7.0% for green responses, and 47.1 ± 7.3% for red responses (n = 7).

Figure 6. Effects of melatonin on HCs intracellularly recorded in isolated carp retina.

A–C, the retina was exposed to moderate light flashes of 500 nm (logI=−0.6) and 680 nm (logI=−0.6) presented alternately at intervals of 3 s. A, melatonin of 25 nm depolarized an H1 cell from a dark membrane potential of −28 to −10 mV and reduced the amplitudes of the light responses. The effects of melatonin were reversed by the addition of 250 nm luzindole. B, MB of 25 μm, like melatonin, depolarized an H1 cell and decreased the response amplitudes. The membrane potential and light responses fully recovered on washout. C, application of a mixture of 10 μm spiperone, 10 μm SCH 23390, 150 μm picrotoxin and 25 μm strychnine slightly depolarized the cell, but hardly changed the light responses. Addition of 25 nm melatonin depolarized the cell from −24 to −8 mV. In association with the membrane depolarization, the light responses to both test flashes were reduced in amplitudes. Co-application of 250 nm luzindole blocked the melatonin effects. The recordings shown in A–C were obtained from three different H1 cells. D, effects of melatonin on a rod HC. Light responses of the rod HC to dim light flashes of 500 nm (logI=−4.0) and 680 nm (logI=−3.0) alternately presented at intervals of 6 s. Melatonin of 25 nm slightly hyperpolarized the cell from a dark membrane potential of −26 to −30 mV, and increased the light responses by about 20%. The effects of melatonin could be reversed by adding 250 nm luzindole. Light signals are indicated by small square waves below the traces.

For as much as MB mimicked the effects of melatonin on glutamate current responses recorded from isolated H1 cells, we also studied how application of MB could modulate the activity of H1 cells. Figure 6B shows that 25 μm MB depolarized an H1 cell from −25 to −9 mV, and reduced the light responses to the test flashes, effects that were basically similar to those of melatonin (Fig. 6A). These effects of MB on the membrane potential and light responses of H1 cells were observed in all five cells tested. On average, the membrane potential of the cells was depolarized by 12.2 ± 2.3 mV, whereas the relative decrease of the amplitude was 35.1 ± 8.4% for green responses and 34.0 ± 7.8% for red responses (n = 5).

Modulation by melatonin of light responsiveness of cone HCs observed in the isolated retina might be a result of modified activity of D2-like dopamine receptors on photoreceptors due to melatonin-caused changes in dopamine release from interplexiform cells and amacrine cells, just like that reported recently (Ribelayga et al. 2004). The melatonin effects could also be a consequence of modulation of receptors for GABA and/or glycine expressed on these cells and/or on neurones presynaptic to these cells (see Kalloniatis & Tomisich, 1999; Yang, 2004 for review). The effects of melatonin on H1 cells were therefore studied in the presence of spiperone (a selective D2-like receptor antagonist), SCH 23390 (a selective and potent D1 receptor antagonist), picrotoxin (a non-selective Cl− channel blocker), and strychnine (a competitive antagonist of glycine receptors), and an example is shown in Fig. 6C. Co-application of 10 μm spiperone, 10 μm SCH 23390, 150 μm picrotoxin and 25 μm strychnine slightly (less than 5 mV) depolarized the cell, but hardly changed the light responses. Application of 25 nm melatonin, under these conditions, further depolarized the cell from −24 μm to −8 mV in 2 min. In association with the membrane depolarization, the light responses to both test flashes were reduced in amplitudes, like those observed in normal Ringer solution. Addition of 250 nm luzindole blocked these effects of melatonin, and both membrane potential and light responses returned to the original levels obtained before the application of melatonin. Such results were consistently obtained in five other H1 cells. On average, the membrane potential of the cells was depolarized by 11.2 ± 3.4 mV, whereas the relative decrease of the amplitude was 21.3 ± 8.4% for green responses and 21.6 ± 6.5% for red responses, respectively (n = 6).

As a comparison, rod HCs were intracellularly recorded and effects of melatonin on these cells were tested. Figure 6D shows that 25 nm melatonin slightly hyperpolarized the cell from a dark membrane potential of −26 to −30 mV and increased the amplitudes by about 20% for both green and red responses. These effects were quite different from those observed in the cone HCs. Again, the effects of melatonin could be reversed by adding 250 nm luzindole. Similar results were observed in eight other rod HCs. On average, the membrane potential of the cells was hyperpolarized by 2.8 ± 0.5 mV, whereas the relative increase of the amplitude was 26.5 ± 6.5% for green responses and 25.7 ± 6.2% for red responses (n = 9).

Effects of melatonin of high concentrations on glutamate currents and light responses of cone HCs

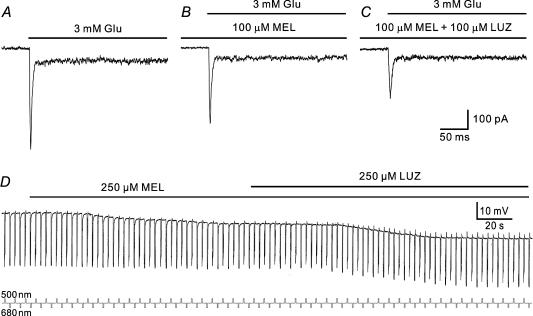

It was previously shown that melatonin of high concentration (500 μm) increased light responses of tiger salamander HCs (Wiechmann et al. 1988). We therefore tested effects of melatonin of high concentrations on both glutamate currents and light responses of H1 cells. When the concentration of melatonin was increased to 10 μm or higher, the effect of melatonin on glutamate current responses of H1 cells was quite different. A comparison of the responses to 3 mm glutamate obtained in normal Ringer solution (Fig. 7A) and in the presence of 100 μm melatonin (Fig. 7B) clearly shows that 100 μm melatonin did not potentiate, but reduced the peak amplitude of the response of an H1 cell (from 475 to 396 pA). Co-application with 250 μm luzindole did not reverse the effect of melatonin and instead further reduced the peak amplitude to 263 pA (Fig. 7C). The results obtained in seven other cells were quite similar. In the presence of 100 μm melatonin the glutamate current was reduced by 24.3 ± 4.4% (P < 0.05). Addition of 250 μm luzindole further reduced the current by 37.4 ± 4.7% (P < 0.05).

Figure 7. Effects of higher concentrations of melatonin glutamate-induced current (A–C) and light responses (D) of carp H1 cells.

A, the current response of an H1 cell, voltage clamped at −60 mV, to 3 mm glutamate in normal Ringer solution. B, the peak response of the cell was reduced in amplitude by incubation with 100 μm melatonin. C, co-application of 100 μm luzindole further reduced the current amplitude. D, effects of 250 μm melatonin on an H1 cell, intracellularly recorded. Melatonin hyperpolarized the cell by 4 mV and slightly reduced the light responses to light flashes of 500 nm (logI=−0.6) and 680 nm (logI=−0.6), which were alternately presented. Co-application of 100 μm luzindole did not reverse the effect of melatonin on the membrane potential and instead further hyperpolarized the cell. Light signals are indicated by small square waves below the traces.

Consistent with the above observation, the effects of melatonin of rank orders of micromolar concentration on the activity of H1 cells intracellularly recorded were also different and could not be reversed by luzindole. In Fig. 7D bath-applied 250 μm melatonin did not depolarize, but hyperpolarized an H1 cell by 4 mV, which was in association with a slight reduction of the light responses. Co-application of 100 μm luzindole did not reverse the effect of melatonin on the membrane potential and instead further hyperpolarized the cell by 6 mV. In addition, luzindole of this concentration tended to enhance the light responses. Such effects of melatonin and luzindole were observed in all five cells tested without exception. On average, the membrane potential of the cells was hyperpolarized by 3.8 ± 1.4 mV, whereas the relative decrease of the amplitude was 15.4 ± 6.1% for green responses and 11.4 ± 4.0% for red responses (n = 5).

Discussion

MT1 receptor on carp cone HC

Although we were not sure from Fig. 1 if all subtypes of HCs (H1, H2, H3 and H4) (Dowling, 1987) were labelled by the anti-MT1 receptor antibody used, because the GAD-immunoreactive HCs could not be clearly identified, it was clear that somata and dendrites of GAD-labelled H1 cells, which are the most distally located of all HCs, were strongly MT1-immunoreactive and the labelling for MT1 was probably localized to the membrane of the H1 cells. This result is basically in agreement with the results obtained in other species by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization (Fujieda et al. 1999; Savaskan et al. 2002; Scher et al. 2002; Wiechmann, 2003; Sallinen et al. 2005).

Modulation by melatonin of glutamate currents of cone HCs

Our results showed that glutamate currents of cone HCs in carp retina were significantly potentiated by melatonin at rank orders of picomolar and nanomolar concentration in a dose-dependent manner. It should be emphasized that these concentrations of melatonin were most likely physiological ones (Faillace et al. 1996; Wan et al. 1999; Saenz et al. 2002; Wiechmann et al. 2003). The increase in maximal currents and the reduction of EC50 (Fig. 3) suggest that the potentiation may be due to an increase in both efficacy and apparent affinity of AMPA receptors for glutamate. The effect of melatonin on KA-induced currents was similar. The melatonin-caused potentiation could be blocked by luzindole, but not by K 185. Even though there is no specific antagonist of the MT1 receptor now available and luzindole works as a competitive antagonist of both MT1 and MT2 receptors (Browning et al. 2000), the different actions of luzindole and K 185 strongly suggest that the potentiation observed may be predominantly mediated by the MT1 receptor. While melatonin has been shown to modulate the GABA receptor on central neurones (Wan et al. 1999; Wu et al. 1999), the present work reports, for the first time, that melatonin could modulate AMPA receptor-mediated glutamatergic transmission by activating the MT1 receptor. It was of interest that melatonin did not change desensitization of the glutamate current, suggesting that melatonin might not interfere with physiological and biochemical processes which are responsible for receptor desensitization (Jones & Westbrook, 1996; Sun et al. 2002).

Melatonin of higher (micromolar) concentrations suppressed the glutamate currents, which could not be blocked by luzindole, suggesting that this effect of melatonin was unlikely mediated by the MT receptor. It is highly possible that this effect of melatonin may be due to an allosteric action caused by melatonin binding to a modulatory site on the AMPA receptor, which may not distinguish subtle difference between melatonin and luzindole. Action at an allosteric binding site on the intra- or extracellular surface of a receptor channel can cause changes in gating properties of the receptor (Changeux & Edelstein, 1998).

Possible mechanisms underlying the potentiation by melatonin of glutamate currents cAMP and cGMP are major intracellular second messengers that mediate melatonin regulation of cell functions (Vanecek, 1998). In a variety of cells melatonin does not alter basal cAMP levels but inhibits intracellular accumulation of cAMP (Reppert et al. 1994, 1995; Martensson & Andersson, 2000). In the carp cone HCs intracellular infusion of cAMP hardly changed the peak amplitude of the glutamate response, while it enhanced the steady-state current (Fig. 5A). This effect was quite different from that of melatonin on the glutamate response. Furthermore, since phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) of AMPA receptor was shown to enhance the activity of the receptor (Roche et al. 1996), the decrease of intracellular accumulation of cAMP by melatonin should have suppressed the glutamate response if the melatonin-caused potentiation observed in this work were mediated through cAMP. All these make it unlikely that cAMP may be a second messenger mediating the melatonin-induced potentiation.

Melatonin increases the intracellular concentration of cGMP in some cells (Vacas et al. 1981; Faillace et al. 1996), but decreases it in others (Vanecek & Vollrath, 1989; Petit et al. 1999; Saenz et al. 2002). Our results showed that, as observed in hybrid bass HCs (McMahon & Ponomareva, 1996), an increase in cGMP concentration by internal infusion reduced the amplitudes of both peak and steady-state glutamate currents (Fig. 5Ba) and the currents were not changed by the addition of 10 nm melatonin in the cGMP-filled cells (Fig. 5Bb). Moreover, a decrease of cGMP concentration in H1 cells by MB potentiated the amplitudes of both peak and steady-state currents, without affecting receptor desensitization, effects that were reminiscent of the melatonin effects on the currents (Fig. 5Cb), and the potentiation of the glutamate response by melatonin was no longer observed in the presence of MB (Fig. 5Cc). It was further found that the effects of melatonin and MB were additive when their concentrations were lower (Fig. 5D). All these results are suggestive of the involvement of cGMP in the melatonin-caused potentiation of the glutamate current. Of course, the possibility that melatonin and cGMP may affect AMPA receptor function through separate, but parallel pathways cannot be excluded.

Physiological roles of melatonin in the outer retina

Melatonin of 25 nm significantly depolarized the H1 cells and reduced light responses of these cells, intracellularly recorded in the isolated, superfused retina, which could be reversed by adding luzindole of 250 nm (Fig. 7A), suggesting that these effects of melatonin were mediated by the activation of the melatonin receptors. It seems unlikely that these effects of melatonin may be a consequence of its action on photoreceptors, since melatonin does not change the electroretinographic a wave in frog retina (Wiechmann et al. 2003) and no MT1 receptors are present on cones (Scher et al. 2002). While the possibility that these melatonin effects on cone HCs may be a consequence of melatonin-caused modulation of other receptors could not be fully ruled out, the fact that the melatonin effects persisted in the presence of spiperone, SCH 23390, picrotoxin and strychnine (Fig. 6C) suggests that the effects must be produced, at least in part, by a direct action of melatonin on the cone HCs. The reasons that melatonin caused the changes in membrane potential and light responses of cone HCs may be complicated. A possibility that activation of the MT1 receptor on H1 cells may lead to a stronger activation of the AMPA receptor on the cone HCs, probably through reducing the intracellular concentration of cGMP, thus making the membrane potential close to the reversal potential of the AMPA receptor (∼0 mV) (Hirasawa et al. 2001). As a result of the reduced driving force, the light responses of these cells were reduced in size. With regard to the effects of melatonin on light responses of HCs, it is noted that 500 μm melatonin hyperpolarizes HCs and increases their light responses in the isolated, superfused tiger salamander retina (Wiechmann et al. 1988). We speculate that the effects of melatonin reported in that work may not be mediated by MT receptors and they could be attributed to the much higher concentration of melatonin (500 μm) used, 104 times higher than the concentration used in the present work, which could produce a possible allosteric action on the AMPA receptor of the HCs. In carp retina, melatonin of 250 μm also hyperpolarized the cone HCs (Fig. 7D), which was not reversed by luzindole.

In the teleost retina, circadian changes in the light responsiveness of L-type cone horizontal (H1) cells have been extensively studied (Wang & Mangel, 1996; Ribelayga et al. 2002, 2004). The light responses of H1 cells at night, compared with those recorded during the subjective day, are generally smaller in amplitude and slower. Moreover, application of melatonin during the subjective day makes the light responses of H1 cells smaller and slower, so that they resemble those typically observed during the subjective night, whereas superfusion of luzindole during the subjective night results in the night-like responses. Such modulation of the light responsiveness is thought be a result of melatonin modified activity of D2-like dopamine receptors on photoreceptors. In the present work, we also found that 25 nm melatonin reduced light responses of carp H1 cells, though no significant changes in response waveforms, similar to those reported in goldfish (Ribelayga et al. 2004), were observed, and these effects of melatonin were mediated by melatonin receptors, most likely the MT1 subtype, on the HCs. It should be indicated that rod signal was not detectable in light responses of H1 cells under our experimental conditions (see Results), even if rod signal could converge onto H1 cells through rod–cone coupling, as suggested by Wang & Mangel (1996). On the other hand, the experiments by Ribelayga et al. (2004) were conducted in fully dark adaptation; in other words, the experimental conditions used for this and the work of Ribelayga et al. work are not quite comparable. Our results therefore raise an alternative intriguing possibility that modulation by melatonin of cone HC light responsiveness may also involve modulation of AMPA receptor-mediated currents of these cells. This may be an additional mechanism underlying the effects of melatonin on cone-driven response of H1 cells that acts in concert with the mechanism proposed by Ribelayga et al. (2004).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (No. 90408003), the Shanghai Commission of Science and Technology (C010607), and the 211 Project of the Ministry of Education of China.

References

- Alonso-Gomez AL, Valenciano AI, Alonso-Bedate M, Delgado MJ. Melatonin synthesis in the greenfrog retina in culture. I. Modulation by the light/dark cycle, forskolin and inhibitors of protein synthesis. Life Sci. 2000;66:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharse JC, Iuvone PM. Circadian clock in Xenopus eye controlling retinal serotonin N-acetyltransferase. Nature. 1983;305:133–135. doi: 10.1038/305133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning C, Beresford I, Fraser N, Giles H. Pharmacological characterization of human recombinant melatonin MT(1) and MT(2) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:877–886. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski A. Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:186–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill GM. Circadian regulation of melatonin production in cultured zebrafish pineal and retina. Brain Res. 1996;708:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ. Allosteric receptors after 30 years. Neuron. 1998;21:959–980. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80616-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE. The Retina: An Approachable Part of the Brain. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dubocovich ML, Rivera-Bermudez MA, Gerdin MJ, Masana MI. Molecular pharmacology, regulation and function of mammalian melatonin receptors. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d1093–1108. doi: 10.2741/1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faillace MP, Keller Sarmiento MI, Rosenstein RE. Melatonin effect on the cyclic GMP system in the golden hamster retina. Brain Res. 1996;711:112–117. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust R, Garratt PJ, Jones R, Yeh LK, Tsotinis A, Panoussopoulou M, Calogeropoulou T, Teh MT, Sugden D. Mapping the melatonin receptor. 6. Melatonin agonists and antagonists derived from 6H-isoindolo[2,1-a] indoles, 5,6-dihydroindolo[2,1-a] isoquinolines, and 6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[c]azepino[2,1-a]indoles. J Med Chem. 2000;43:1050–1061. doi: 10.1021/jm980684+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujieda H, Hamadanizadeh SA, Wankiewicz E, Pang SF, Brown GM. Expression of mt1 melatonin receptor in rat retina: evidence for multiple cell targets for melatonin. Neuroscience. 1999;93:793–799. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa H, Shiells R, Yamada M. Blocking AMPA receptor desensitization prolongs spontaneous EPSC decay times and depolarizes H1 horizontal cells in carp retinal slices. Neurosci Res. 2001;40:217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Luo DG, Shen Y, Zhang AJ, Yang R, Yang XL. AMPA receptor is involved in transmission of cone signal to ON bipolar cells in carp retina. Brain Res. 2004;1002:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuvone PM, Gan J. Functional interaction of melatonin receptors and D1 dopamine receptors in cultured chick retinal neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2179–2185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV, Westbrook GL. The impact of receptor desensitization on fast synaptic transmission. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalloniatis M, Tomisich G. Amino acid neurochemistry of the vertebrate retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:811–866. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A, Yamada M. S-potentials in the dark-adapted retina of the carp. J Physiol. 1972;227:261–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasater EM. Ionic currents of cultured horizontal cells isolated from white perch retina. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:499–513. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GL, Li P, Yang XL. Melatonin modulates gamma-aminobutyric acid (A) receptor-mediated currents on isolated carp retinal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2001;301:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Shen Y, Yang XL. Desensitization of AMPA receptors on horizontal cells isolated from crucian carp retina. Neurosci Res. 1998;31:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson LG, Andersson RG. Is Ca2+ the second messenger in the response to melatonin in cuckoo wrasse melanophores? Life Sci. 2000;66:1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon DG, Ponomareva LV. Nitric oxide and cGMP modulate retinal glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2307–2315. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit L, Lacroix I, De Coppet P, Strosberg AD, Jockers R. Differential signaling of human Mel1a and Mel1b melatonin receptors through the cyclic guanosine 3′-5′-monophosphate pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Godson C, Mahle CD, Weaver DR, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF. Molecular characterization of a second melatonin receptor expressed in human retina and brain: the Mel1b melatonin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8734–8738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Ebisawa T. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron. 1994;13:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelayga C, Wang Y, Mangel SC. Dopamine mediates circadian clock regulation of rod and cone input to fish retinal horizontal cells. J Physiol. 2002;544:801–816. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelayga C, Wang Y, Mangel SC. A circadian clock in the fish retina regulates dopamine release via activation of melatonin receptors. J Physiol. 2004;554:467–482. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KW, O'Brien RJ, Mammen AL, Bernhardt J, Huganir RL. Characterization of multiple phosphorylation sites on the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit. Neuron. 1996;16:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz DA, Turjanski AG, Sacca GB, Marti M, Doctorovich F, Sarmiento MI, Estrin DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiological concentrations of melatonin inhibit the nitridergic pathway in the Syrian hamster retina. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:31–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallinen P, Saarela S, Ilves M, Vakkuri O, Leppaluoto J. The expression of MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptor mRNA in several rat tissues. Life Sci. 2005;76:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan E, Wirz-Justice A, Olivieri G, Pache M, Krauchi K, Brydon L, Jockers R, Muller-Spahn F, Meyer P. Distribution of melatonin MT1 receptor immunoreactivity in human retina. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:519–526. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher J, Wankiewicz E, Brown GM, Fujieda H. MT(1) melatonin receptor in the human retina: expression and localization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:889–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Chan CW, Brown GM, Pang SF, Silverman M. Studies of the renal action of melatonin: evidence that the effects are mediated by 37 kDa receptors of the Mel1a subtype localized primarily to the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule. FASEB J. 1997;11:93–100. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.1.9034171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden D, Yeh LK, Teh MT. Design of subtype selective melatonin receptor agonists and antagonists. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1999;39:335–344. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19990306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E. Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosini G. Melatonin circadian rhythm in the retina of mammals. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:599–612. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosini G, Fukuhara C. Photic and circadian regulation of retinal melatonin in mammals. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:364–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacas MI, Sarmiento MI, Cardinali DP. Melatonin increases cGMP and decreases cAMP levels in rat medial basal hypothalamus in vitro. Brain Res. 1981;225:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanecek J. Cellular mechanisms of melatonin action. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:687–721. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanecek J, Vollrath L. Melatonin inhibits cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accumulation in the rat pituitary. Brain Res. 1989;505:157–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q, Man HY, Liu F, Braunton J, Niznik HB, Pang SF, Brown GM, Wang YT. Differential modulation of GABAA receptor function by Mel1a and Mel1b receptors. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:401–403. doi: 10.1038/8062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mangel SC. A circadian clock regulates rod and cone input to fish retinal cone horizontal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4655–4660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann AF. Differential distribution of Mel1a and Mel1c melatonin receptors in Xenopus laevis retina. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann AF, Udin SB, Summers Rada JA. Localization of Mel1b melatonin receptor-like immunoreactivity in ocular tissues of Xenopus laevis. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann AF, Vrieze MJ, Dighe R, Hu Y. Direct modulation of rod photoreceptor responsiveness through a Mel1c melatonin receptor in transgenic Xenopus laevis retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4522–4531. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann AF, Yang XL, Wu SM, Hollyfield JG. Melatonin enhances horizontal cell sensitivity in salamander retina. Brain Res. 1988;453:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FS, Yang YC, Tsai JJ. Melatonin potentiates the GABA(A) receptor-mediated current in cultured chick spinal cord neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1999;260:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HP, Luo DG, Yang XL. Signals from cone photoreceptors to L-type horizontal cells are differentially modulated by low calcium in carp retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1411–1419. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HP, Zhao JW, Yang XL. Cholinergic and dopaminergic amacrine cells differentially express calcium channel subunits in the rat retina. Neuroscience. 2003;118:763–768. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL. Characterization of receptors for glutamate and GABA in retinal neurons. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL, Fan TX, Shen W. Effects of prolonged darkness on light responsiveness and spectral sensitivity of cone horizontal cells in carp retina in vivo. J Neurosci. 1994;14:326–334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00326.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL, Tauchi M, Kaneko A. Quantitative analysis of photoreceptor inputs to external horizontal cells in the goldfish retina. Jpn J Physiol. 1982;32:399–420. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.32.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL, Tauchi M, Kaneko A. Convergence of signals from red-sensitive and green-sensitive cones onto L-type external horizontal cells of the goldfish retina. Vision Res. 1983;23:371–380. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL, Tornqvist K, Dowling JE. Modulation of cone horizontal cell activity in the teleost fish retina. I. Effects of prolonged darkness and background illumination on light responsiveness. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2259–2268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02259.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawilska JB, Berezinska M, Rosiak J, Vivien-Roels B, Skene DJ, Pevet P, Nowak JZ. Daily variation in the concentration of melatonin and 5-methoxytryptophol in the goose pineal gland, retina, and plasma. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2003;134:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(03)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JW, Yang XL. Glutamate transporter EAAC1 is expressed on Muller cells of lower vertebrate retinas. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:89–95. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]