Abstract

The carotid body (CB) is an arterial chemoreceptor, bearing specialized type I cells that respond to hypoxia by closing specific K+ channels and releasing neurotransmitters to activate sensory axons. Despite having detailed information on the electrical and neurochemical changes triggered by hypoxia in CB, the knowledge of the molecular components involved in the signalling cascade of the hypoxic response is fragmentary. This study analyses the mouse CB transcriptional changes in response to low PO2 by hybridization to oligonucleotide microarrays. The transcripts were obtained from whole CBs after mice were exposed to either normoxia (21% O2), or physiological hypoxia (10% O2) for 24 h. The CB transcriptional profiles obtained under these environmental conditions were subtracted from the profile of control non-chemoreceptor adrenal medulla extracted from the same animals. Given the common developmental origin of these two organs, they share many properties but differ specifically in their response to O2. Our analysis revealed 751 probe sets regulated specifically in CB under hypoxia (388 up-regulated and 363 down-regulated). These results were corroborated by assessing the transcriptional changes of selected genes under physiological hypoxia with quantitative RT-PCR. Our microarray experiments revealed a number of CB-expressed genes (e.g. TH, ferritin and triosephosphate isomerase) that were known to change their expression under hypoxia. However, we also found novel genes that consistently changed their expression under physiological hypoxia. Among them, a group of ion channels show specific regulation in CB: the potassium channels Kir6.1 and Kcnn4 are up-regulated, while the modulatory subunit Kcnab1 is down-regulated by low PO2 levels.

The sympathoadrenal lineage of the neural crest gives rise to the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and the carotid body. Although they share a common developmental origin, the two neuronal cell types become specialized for different physiological roles. The adrenal medulla (AM) is involved in catecholamine release in response to stress. The carotid body (CB) is an arterial chemoreceptor composed of modified neurones, the glomus type I cells, that respond to hypoxia by closing specific K+ channels and releasing neurotransmitters to activate sensory axons (Gonzalez et al. 1994; Peers, 2004). In turn, the neural processing of this signal sets the appropriate respiratory response.

We are interested in the process of oxygen sensing by CB chemoreceptor cells. This process is turned on after birth in mammals, and accounts for the respiratory and cardiovascular compensatory adaptations organized in response to both acute (lasting seconds to minutes) hypoxia (Prabhakar, 2000) and the sustained hypoxia experienced during acclimatization to high altitudes (Bisgard, 2000). In spite of the detailed knowledge of the electrophysiological and neurochemical changes in CB function generated by hypoxia (Gonzalez et al. 2003), the molecular nature of the components of the signalling cascade responsible for the hypoxic response is partially known (Prabhakar, 2001; Paulding et al. 2002).

In this work we have undertaken a global survey of hypoxia-dependent transcriptional changes to search for the components of the functional module of proteins participating in the physiological response to low PO2. In order to uncover genes differentially expressed in CB cells, we use the hybridization of CB mRNA with oligonucleotide microarrays of mouse genes. The transcripts are obtained from mice that were exposed to either normoxia (21% O2) or to physiological hypoxia (10% O2) for 24 h. The transcriptional profiles obtained for CB cells under these environmental conditions are compared and subtracted from the profile of control (non-chemoreceptor) AM cells exposed to the same PO2 conditions. The subsequent bioinformatical analysis reveals genes involved in the hypoxic response.

Methods

Congenic C57BL/6J01aHsd littermate female mice of 12 weeks of age were obtained from Harlan Laboratories. The experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Valladolid.

Three experiments were performed. In each, two groups of five mice were subjected to normoxia (21%) or hypoxia (10%), for 24 h in a modified plethysmography cage. The groups subjected to normoxia or hypoxia will hereafter be referred to as control and experimental groups. All animals were maintained on a 12 h-light cycle, with food and water ad libitum during the experimental period.

After the experiment, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the adrenal medulla and carotid bodies were dissected and stored in RNAlater™ (Ambion) at 4°C prior to the RNA purification step carried out 24 h later. The organs from each experiment were pooled according to each experimental condition. All the carotid body organs (a total of 10 per experimental group) were used for the RNA preparation. Only one adrenal medulla from each mouse (a total of 5 per group) was used, to compensate for the tissue size difference. The remainder of the adrenal medulla samples were stored at –20°C in RNAlater for future use.

RNA purification, amplification and labelling

RNA was purified from the tissue samples using the RNAqueous kit (Ambion), which included a DNAseI treatment to avoid genomic DNA contamination. The quality and purity of the adrenal medulla RNA was assayed by OD measurement at 260 and 280 nm and by electrophoresis on agarose gels. The RNA yields from carotid body samples were too low for detection on gels (approximately 200 ng/10 carotid bodies). An assumption was made that the quality would be similar to the adrenal medulla sample processed in parallel. The whole carotid body total RNA preparation proceeded directly to the amplification phase. Five hundred nanograms of adrenal medulla total RNA was used for amplification.

Two rounds of linear amplification by in vitro transcription were performed following a protocol based on the ‘Eberwine method’ (Eberwine et al. 1992). Briefly, double stranded cDNA was synthesized using the total RNA as template primed with an oligonucleotide containing the T7 RNA polymerase recognition site plus an oligo-dT segment in order to select for the polyA-mRNA population. After purification, this cDNA was in vitro transcribed resulting in the first amplification step. A second round of amplification followed, using 500 ng of the amplified RNA from each sample. Then, a first strand of cDNA was synthesized from the amplified RNA using random hexamers as primers. This resulted in an estimated average size of cDNA fragments of 600 bp. The second cDNA strand was primed with the T7-oligodT primer and the fragments produced were subjected to in vitro transcription using a biotinylated mix of nucleotides. Therefore, we were linearly amplifying fragments of similar size from the 3′ ends of the mRNAs present in the original sample. The biotinylated RNA was ready for hybridization to the chips.

We used the MessageAmp kit (Ambion) for the first round of amplification and the generation and purification of cDNA from the amplified RNA. The Enzo kit (Affymetrix) was used for the second in vitro transcription RNA amplification and biotin labelling.

Oligonucleotide array hybridization and detection

Fifteen micrograms of the biotinylated and fragmented probes were hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse MOE430A arrays at 45°C for 16 h, following the manufacturer's protocols. After washes, the arrays were labelled with anti-biotin–streptavidin–phycoerythrin antibody and scanned with an Agilent Gene Scanner G2500A.

Microarray data analysis

The analysis of single array gene expression and the comparative expression between samples was performed with the statistical algorithms implemented in the Affymetrix Microarray Analysis Suite v5.0 (MAS 5.0). Global scaling was carried out for each pair of probe arrays using an arbitrary target intensity of 100. The MAS 5.0 statistically determined the presence of a transcript on a given chip (detection P-value cut-offs α1 and α2 were 0.05 and 0.065, respectively). The detection call (presence, P, versus absence, A) was used to assemble the gene expression profile of each tissue under study.

After robust normalization with a perturbation factor of 1.1, the signal intensity values for each pair of control/experimental arrays in a given experiment were used to estimate a change P-value and its associated change call in gene expression. A quantitative estimation of the change in gene expression was derived from the signal-log ratio value calculated in MAS 5.0. Only genes that showed consistent change calls in their expression in the three experiments were selected for further study.

In parallel to the above MAS 5.0-based analysis, we performed an automatic study in GenePublisher (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/GenePublisher) (Knudsen et al. 2003) in order to compare both types of analysis and extract the most significant changes in gene expression.

Descriptions for genes selected for analysis were obtained from the Affymetrix Analysis Center. Data mining with gene ontology classification of the selected transcripts, and gene ontology comparisons between tissues were carried out in the FatiGO server (http://fatigo.bioinfo.cnio.es) (Al-Shahrour et al. 2004).

The software PATHWAYASSIST and the ResNet™ database (Stratagene) were used to explore the networks of interactions where the physiological hypoxia-regulated genes are potentially involved.

Real time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from normoxic and hypoxic adrenal medulla with the RNaqueous micro kit (Ambion). The RNA samples were treated with deoxyribonuclease I (Ambion) to avoid contaminating genomic DNA (given the intronless nature of the mouse GAPDH gene). cDNA synthesis was performed with MuLV-RT from 1 μg total RNA. Primer sets and TaqMan probes for two selected control genes were: mGAPDH: 5′- TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTG-3′, 5′-GATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTT-3′ and 5′-FAM-TGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATGATGACATCA-BHQ2-3′; mGus: 5′-CAATGGTACCGGCAGCC-3′, 5′-AAGCTAGAAGGGACAGGCATGT-3′ and 5′-FAM-TACGGGAGTCGGGCCCAGTCTTG-BHQ2-3′. Real-time amplifications were carried out in a Rotor-Gene RG3000 (Corbett Research) thermocycler.

Primer sets and TaqMan probes for experimental genes (Agouti-related protein, Peroxisomal Δ3, and Serpinh1) were obtained as ‘Assays-on-demand’ kits Mm00475829 g1, Mm00478725 m1, and Mm438056 m1 from ABI.

Amplifications were performed in 25 μl final volume, using 12.5 μl of Absolute QPCR dUTP mix (ABgene), 0.5 μl of UNG (1 μμl−1, ABI), 1 μl of the corresponding primer/probe mix and 1 μl of template DNA (70 ng μl−1). Cycling conditions were: 2 min at 50°C, 15 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s followed by 60°C for 1 min. Amplification efficiencies for all the genes studied were determined by serial dilutions of template cDNA. All samples were amplified in triplicates and the mean critical threshold (CT) value for each transcript was normalized to m-Gus because of its constant expression in our microarray experiments, and the lack of a reported regulation by changes in environmental PO2. As reaction efficiencies were similar (differences < 0.1), the ΔΔCT method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001) was used to study variations in gene expression in the two conditions tested (normoxia and hypoxia).

Results

Experimental design

The transcriptional profiles of tissues and cells exposed to low PO2 levels have been already documented using microarray chip technologies (e.g. Beitner-Johnson et al. 2001; Gilbert et al. 2003; Hoshikawa et al. 2003; Koike et al. 2004; Aravindan et al. 2005). However, the low PO2 levels (< 20 mmHg), sometimes strict anoxia, used in some studies trigger a general cellular stress response in every tissue.

We are interested in the transcriptional changes generated by levels of hypoxia that would only generate a response in chemosensory organs. This range of PO2, about 10% (70 mmHg) for CB chemoreceptor cells, is considered a physiological hypoxia (Gonzalez, 1998), and mimics the oxygen levels found by an organism at high altitude. Thus, the selection of this PO2 will allow us to differentially identify the molecular components of the signalling cascade related to the sensitivity to physiological hypoxia.

We have selected for this study a hypoxia level of 10%PO2 that produces compensatory hyperventilation reflexes without generating a broad hypoxic cellular stress. The respiratory response to this PO2 level on C57BL/6J01aHsd mice was verified by plethysmography (results not shown). We selected a sustained hypoxia protocol because it mimics the PO2 stimulus that an organism experiences upon exposure to high altitude (at around 5000 meters above sea level). The selection of 24 h as the time of exposure for the experiments was due to the reported decline in transcription of hypoxia-regulated genes after 24 h of hypoxia treatment (Czyzyk-Krzeska et al. 1994).

The selection of the adrenal medulla as a control tissue for subtractive filtering of the CB array data is based on their common developmental origin, their neural and catecholamine-releasing phenotype, and their differential sensitivity to changes in environmental PO2. During embryonic life, the AM chromaffin cells respond to low PO2 to secrete catecholamines (Slotkin & Seidler, 1988). However, in adult life the AM cells are not sensitive to hypoxia levels in the physiological range for a chemoreceptor (Thompson & Nurse, 2000). Moreover, this hypoxia level fails to induce the transcription of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the limiting enzyme of the catecholamine synthesis pathway, in AM and superior cervical ganglion cells, while triggering a consistent increase in transcription in CB chemoreceptor cells (Czyzyk-Krzeska et al. 1992).

General description of microarray parameters

The two rounds of linear amplification rendered around 30 μg of double stranded cDNA, with 260/280 absorbance ratios of 2.02–2.08 indicating a high level of RNA purity. The preparation of total RNA showed tight and clear bands at the expected size for the ribosomal RNA with no signs of degradation.

The quality for the hybridization signals obtained in the microarrays was evaluated through the standard Affymetrix guidelines. Table 1 shows these parameters. The M/3′ values measured in the mouse GAPDH control probe sets point to a good amplification of the transcripts. The 5′/3′ ratio was not used since we are amplifying fragments from the 3′ end of each mRNA. The percentage of present (P) calls (average 50.2%) is also in the accepted range by Affymetrix. The reliability index for triplicates is 0.98, which indicates an adequate level of reproducibility. This is also evidenced by the number of concordant calls in the triplicates, which averages 84.2%.

Table 1.

Parameters used to evaluate the quality of the microarray hybridization signals

| Scale factor | M/3′ | Present calls | Concordant calls | Reliability index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB normoxia | 0.73 | 3.87 | 47.40 | 84.5 | 0.98 |

| CB hypoxia | 0.77 | 3.17 | 49.57 | 85 | 0.99 |

| AM normoxia | 0.55 | 1.80 | 51.80 | 83 | 0.98 |

| AM hypoxia | 0.78 | 1.76 | 51.47 | 84.3 | 0.98 |

The M/3′ value was obtained from the m-GAPDH control probe sets. The reliability index is the Cronbach's α coefficient estimated from multiple regression analysis of the triplicate hybridization values.

Gene expression profiles of carotid body and adrenal medulla under normoxia

The detection call assigned by MAS 5.0 revealed 9286 transcripts of the MOE430A chip expressed in the mouse CB, and 9975 transcripts expressed in AM.

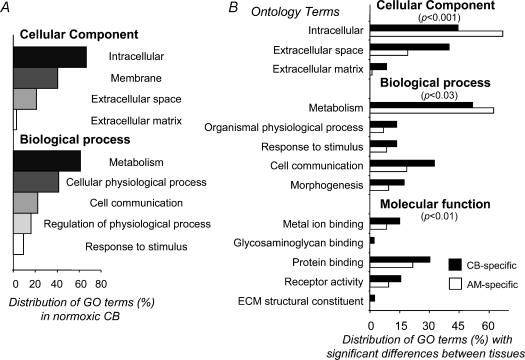

The gene expression profiles of the two organs (genes with P calls in the three chips) were studied by gene ontology (GO) classification (as defined by the GO consortium, http://www.geneontology.org; Ashburner et al. 2000). The overall profiles show a similar GO distribution in the three general ontology classes. Figure 1A shows this distribution for CB as an example.

Figure 1. Gene ontology comparisons of CB and AM gene expression under normoxic conditions.

A, general ontology classification of CB-expressed genes in two ontology terms. B, comparisons of GO distributions among CB and AM-specific genes. The P-values calculated for each comparison represent the statistical significance of the paired distributions, as evaluated with Fisher's exact test for 2 × 2 contingency tables with a P-value adjusted for multiple testing using the FDR procedure (Reiner et al. 2003). Only those GO terms with significant differences (P < 0.05) are shown in the figure.

A remarkably different pattern was observed after exclusion of genes expressed in both organs. This procedure rendered 800 genes specifically expressed in CB, while 1449 genes were found to be AM-specific. These profiles show significant differences in their distribution of gene ontology terms (Fig. 1B). Differences were evaluated with Fisher's exact test for 2 × 2 contingency tables with the P-value adjusted for multiple testing using the false discovery rate procedure (Reiner et al. 2003). Classification according to the cellular compartment ontology level showed a higher proportion of CB-specific gene products associated with the extracellular space and matrix, while AM gene expression resulted in a higher abundance of intracellular proteins.

Of special interest for this work was an enrichment of CB gene expression in genes related to cell communication and response to stimulus (biological process ontology), and metal-ion binding, protein binding, and receptor activity (molecular function ontology) (Fig. 1B).

Analysis of carotid body gene expression in response to physiological hypoxia

We selected probe sets that consistently showed a change in expression in the three experiments based on the change calls (increase, I; decrease, D; or no change, NC) generated by MAS 5.0 (see Methods). The change calls defined as medium increment (MI) or medium decrement (MD) were considered as NC. Entries with three equivalent change calls were considered for further analysis.

The selection of CB genes showing changes in gene expression under hypoxia treatment provided a list of 404 probe sets that increased their expression, and 391 probe sets that decreased their expression.

Because of the non-chemosensory nature of several cell types present in the whole CB tissue used for our array experiments, we designed a subtractive analysis of the transcriptional changes obtained in response to physiological hypoxia. We selected the probe sets in AM chips with consistent changes in gene expression upon physiological hypoxia. Sixty-three probe sets present in AM cells showed an increased gene expression, while 177 probe sets reduced their expression in response to hypoxia.

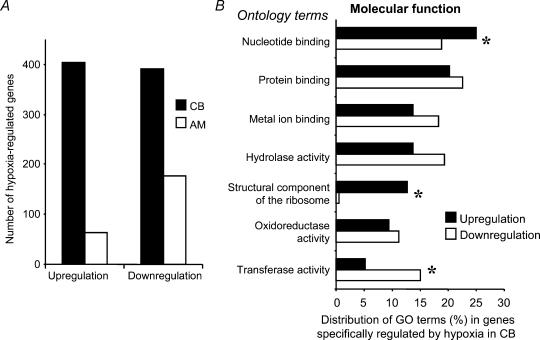

A fundamental, though expected, conclusion can be deduced from these numbers when compared to those obtained for CB (Fig. 2A): the adult carotid body is more sensitive than the adrenal medulla to physiological hypoxia, corroborating the ‘adequate’ stimuli classical theory (Sherrington, 1947), and this sensitivity is reflected in assessable transcriptional changes.

Figure 2. Changes in CB gene transcription under 10% O2 hypoxia.

A, comparison of the total number of genes regulated by hypoxia between CB and AM. B, gene ontology classification of genes regulated by hypoxia specifically in the CB. The main ontology classes based on molecular function are represented separately as up-regulated or down-regulated gene groups. Statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences in some gene ontology groups are marked by asterisks.

The genes showing hypoxia regulation in non-chemosensory tissues were then subtracted from the CB gene list in order to highlight physiological hypoxia-specific CB genes. After performing this specificity filter, we ended up with 388 probe sets with increased, and 363 probe sets with decreased, signal.

The GO classification of the genes regulated specifically in the CB reveals genes mainly related to protein and nucleotide binding, hydrolase activity, and interestingly in the context of oxygen sensing, genes related to metal ion binding and oxidoreductase activity (Fig. 2B).

A comparison of the ontology terms that define the hypoxia up- and down-regulated CB genes demonstrated significant differences (asterisks in Fig. 2B) in genes participating in nucleotide binding, in the structural constituent of the ribosome (both more abundant in the up-regulated gene list), and in transferase activity (more abundant in the down-regulated gene list). A catalogue of hypoxia-regulated CB genes with consistent change calls, change fold > 2.5, and change P-values < 0.001 is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genes of the CB up-regulated or down-regulated in response to 10% O2 hypoxia for 24 h

| Probe set ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Fold | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant 2.5-fold increase P-value < 0.001 | ||||

| 1438211_s_at | D site albumin promoter binding protein | Dbp | 13.03 | 0.000021 |

| 1448276_at | transmembrane 4 superfamily member 7 | Tm4sf7 | 7.09 | 0.000020 |

| 1451185_at | Splicing factor 3b, subunit 5 | 1110005L13Rik | 6.31 | 0.000721 |

| 1451208_at | eukaryotic translation termination factor 1 | Etf1 | 5.84 | 0.000892 |

| 1427747_a_at | lipocalin 2 | Lcn2 | 5.78 | 0.000085 |

| 1428942_at | metallothionein 2 | Mt2 | 5.36 | 0.000020 |

| 1422185_a_at | diaphorase 1 (NADH) | Dia1 | 4.66 | 0.000020 |

| 1449036_at | ring finger protein 128 | Rnf128 | 4.59 | 0.000148 |

| 1422557_s_at | metallothionein 1 | Mt1 | 4.21 | 0.000020 |

| 1423145_a_at | titin-cap | Tcap | 4.04 | 0.000020 |

| 1452777_a_at | NUB1, a NEDD8-interacting protein | 6330412F12Rik | 4.03 | 0.000669 |

| 1449525_at | flavin containing monooxygenase 3 | Fmo3 | 3.91 | 0.000027 |

| 1426464_at | nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1 | Nr1d1 | 3.84 | 0.000098 |

| 1449851_at | period homolog 1 (Drosophila) | Per1 | 3.77 | 0.000129 |

| 1418318_at | ring finger protein 128 | Rnf128 | 3.13 | 0.000148 |

| 1435386_at | Von Willebrand factor homolog | Vwf | 3.07 | 0.000020 |

| 1418936_at | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene, protein F | Maff | 3.07 | 0.000020 |

| 1448181_at | Kruppel-like factor 15 | Klf15 | 2.92 | 0.000036 |

| 1442025_a_at | expressed sequence AI467657 | AI467657 | 2.91 | 0.000037 |

| 1418025_at | basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 | Bhlhb2 | 2.83 | 0.000094 |

| 1453678_at | methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1 | Mbd1 | 2.79 | 0.000512 |

| 1428955_x_at | solute carrier family 9, isoform 3 regulator 2 | Slc9a3r2 | 2.78 | 0.000021 |

| 1451121_a_at | glioma tumour suppressor candidate region gene 2 | Gltscr2 | 2.74 | 0.000037 |

| 1418296_at | FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 5 | Fxyd5 | 2.72 | 0.000020 |

| 1432466_a_at | apolipoprotein E | Apoe | 2.71 | 0.000024 |

| 1426383_at | cryptochrome 2 (photolyase-like) | Cry2 | 2.70 | 0.000033 |

| 1436046_x_at | ribosomal protein L29 | Rpl29 | 2.68 | 0.000036 |

| 1448839_at | DNA segment, Chr 17, ERATO Doi 288, | D17Ertd288e | 2.66 | 0.000168 |

| 1449461_at | retinol binding protein 7, cellular | Rbp7 | 2.63 | 0.000250 |

| 1419674_a_at | dipeptidase 1 (renal) | Dpep1 | 2.63 | 0.000026 |

| 1416125_at | FK506 binding protein 5 | Fkbp5 | 2.61 | 0.000666 |

| 1451130_at | RIKEN cDNA 2010315L10 gene | 2010315L10Rik | 2.61 | 0.000020 |

| 1448862_at | intercellular adhesion molecule 2 | Icam2 | 2.60 | 0.000020 |

| 1419874_x_at | zinc finger protein 145 | Zfp145 | 2.58 | 0.000338 |

| 1428538_s_at | retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) 2 | Rarres2 | 2.56 | 0.000543 |

| 1423233_at | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), delta | Cebpd | 2.56 | 0.000020 |

| 1436586_x_at | ribosomal protein S14 | Rps14 | 2.52 | 0.000023 |

| 1452674_a_at | RIKEN cDNA 1200009C21 gene (eIF-3 p25) | 1200009C21Rik | 2.52 | 0.000020 |

| Concordant 2.5-fold decrease P-value < 0.001 | ||||

| 1420465_s_at | major urinary protein 1 | Mup1 | −9.83 | 0.000020 |

| 1450779_at | fatty acid binding protein 7, brain | Fabp7 | −4.91 | 0.000049 |

| 1427884_at | procollagen, type III, alpha 1 | Col3a1 | −3.49 | 0.000023 |

| 1420855_at | elastin | Eln | −3.10 | 0.000020 |

| 1425425_a_at | Wnt inhibitory factor 1 | Wif1 | −3.09 | 0.000073 |

| 1448755_at | procollagen, type XV | Col15a1 | −2.89 | 0.000202 |

| 1424556_at | pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 | Pycr1 | −2.79 | 0.000113 |

| 1422789_at | aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1, subfamily A2 | Aldh1a2 | −2.78 | 0.000767 |

| 1417403_at | ELOVL family member 6 | Elovl6 | −2.74 | 0.000201 |

| 1420725_at | trimethyllysine hydroxylase, epsilon | Tmlhe | −2.70 | 0.000022 |

| 1426460_a_at | UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 | Ugp2 | −2.60 | 0.000569 |

| 1419519_at | insulin-like gth factor 1 | Igf1 | −2.57 | 0.000046 |

| 1418937_at | deiodinase, iodothyronine, type II | Dio2 | −2.51 | 0.000025 |

The genes selected for the table are the ones that show consistent (equivalent change calls), > 2.5-fold, and significant (P < 0.001) changes in transcription.

Although the absent (A) call assigned by MAS 5.0 to some probe sets might be due to unreliable hybridization, we studied those probe sets with concordant absent calls (three A) in either control or experimental CB chips that consistently change their expression in the opposing O2 condition in a tissue-specific manner. This strategy identifies CB genes that are switched-ON and -OFF under physiological hypoxia. We found 18 genes switched-ON and 3 genes switched-OFF in CB (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genes switched-ON and OFF in the CB transcriptome in response to physiological hypoxia

| Probe set ID | Gene name | Gene symbol | Fold |

|---|---|---|---|

| CB hypoxia switched-ON genes | |||

| 1451185_at | RIKEN cDNA 1110005L13 gene | 1110005L13Rik | 6.31 |

| 1451208_at | eukaryotic translation termination factor 1 | Etf1 | 5.84 |

| 1452777_a_at | RIKEN cDNA 6330412F12 gene | 6330412F12Rik | 4.03 |

| 1426464_at | nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1 | Nr1d1 | 3.84 |

| 1419100_at | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade A, member 3 N | Serpina3n | 3.12 |

| 1418936_at | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene, protein F | Maff | 3.07 |

| 1430838_x_at | methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1 | Mbd1 | 2.63 |

| 1420772_a_at | delta sleep inducing peptide, immunoreactor | Dsip1 | 2.58 |

| 1427367_at | cDNA sequence BC026645 | BC026645 | 2.35 |

| 1448643_at | RIKEN cDNA 1110003H09 gene | 1110003H09Rik | 2.30 |

| 1416080_at | a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 15 (metargidin) | Adam15 | 2.28 |

| 1422257_s_at | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily b, polypeptide 20 | Cyp2b20 | 2.08 |

| 1460371_at | heat shock protein 12B | Hspa12b | 1.99 |

| 1436828_a_at | tumour protein D52-like 2 | Tpd52l2 | 1.88 |

| 1427034_at | angiotensin converting enzyme | Ace | 1.84 |

| 1423122_at | arginine vasopressin-induced 1 | Avpi1 | 1.84 |

| 1419722_at | protease, serine, 19 (neuropsin) | Prss19 | 1.81 |

| 1455741_a_at | endothelin converting enzyme 1 | Ece1 | 1.73 |

| CB hypoxia switched-OFF genes | |||

| 1426154_s_at | major urinary protein 1 | Mup1 | −9.83 |

| 1425673_at | LIM domain containing preferred translocation partner in lipoma | Lpp | −2.19 |

| 1440201_at | mitogen activated protein kinase 10 | Mapk10 | −1.59 |

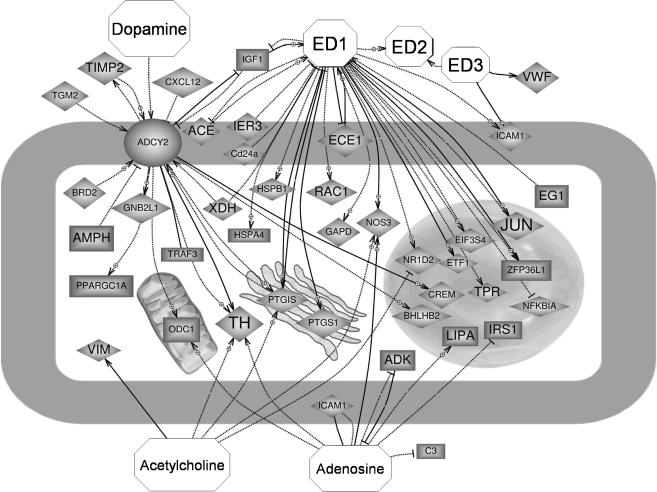

Besides cataloguing CB genes regulated by hypoxia, we looked at the functional interactions between those genes in order to highlight putative signalling cascades involved in the hypoxic response. Using the software PATHWAYASSIST and the ResNet™ database we mined CB hypoxia-regulated genes identified in our microarray experiments that bear direct functional interactions with molecules known to be players in the chemoreception pathway in the CB. Figure 3 shows, as an example, the interaction network resulting from selecting genes functionally related to the neurotransmitters dopamine, acetylcholine and adenosine, and the angiogenic peptide endothelin. Other networks identified for VEGF, NO and H2O2 are presented as online Supplemental material.

Figure 3. Functional interactions among genes specifically regulated in the CB under physiological hypoxia with molecules (octagons) known to be released by type I cells upon hypoxic activation.

Up-regulated genes are shown as diamonds and down-regulated ones as rectangles. Dashed and continuous lines represent different ways of molecular interaction. Arrows point to positive regulation, while blunt-end lines reflect negative regulation. Gene names and references to interactions shown can be found in the Supplemental material. Other networks are also attached as Supplemental material.

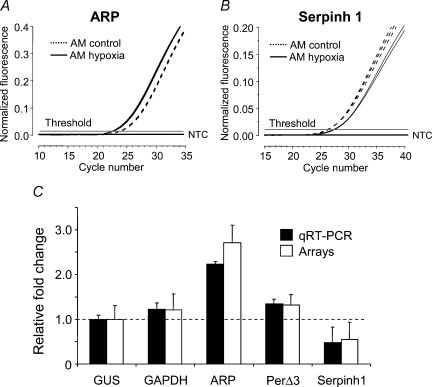

Array validation by real-time RT-PCR

Three genes were selected for qRT-PCR experiments based on their consistent change in expression under hypoxia in both organs studied, as determined by the array experiments. Two control genes were selected for standardization of gene expression: glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-glucuronidase (Gus), based on their presumed lack of transcriptional regulation under the experimental conditions tested in our experiments. However, GAPDH, though widely used as a standard for quantitative gene expression studies, is known to change its transcriptional levels under hypoxia (Zhong & Simons, 1999). Our array experiments showed a mild increase in GAPDH expression (1.2-fold) in response to physiological hypoxia.

The lack of change of Gus in response to physiological hypoxia in our arrays led us to select this gene as a control for normalization.

Figure 4 shows the qRT-PCR results, after normalization, in comparison with the transcriptional changes evidenced by the chip arrays. The fold-changes obtained in these experiments are comparable to those obtained in the array experiments for each gene studied. This demonstrates the reliability of the arrays hybridization, and supports the biological information extracted from the data.

Figure 4. Quantitative real-time PCR to test our microarray results for consistency.

A and B, amplification curves for genes ARP and Serpinh1 from AM total RNA exposed to normoxia (dashed lines) or 10% O2 (continuous lines) for 24 h. C, relative quantification of mRNA expression by PCR for five genes was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method using m-Gus as an internal control. Error bars represent standard deviations obtained from triplicate amplifications. These results are shown compared to gene transcription obtained in our array experiments relative to m-Gus. The dashed line marks the baseline for transcription set by the internal control mRNA.

Discussion

This work represents a genomic-scale approach aimed at the identification of genes that show a regulated expression under physiological hypoxia in CB chemoreceptor cells.

We have to take into account that the tissues used for generating the hybridizing probes for our arrays are composed of several cell types. Thus, the transcriptional profiles we have obtained correspond in the CB to those of type I chemoreceptor cells, type II glia-like sustentacular cells, and blood vessel cells. In the AM they represent chromaffin cells, blood vessel cells, and some sympathetic neurones.

Both the CB type II cells and the chromaffin AM cells do not respond to physiological hypoxia (Lopez-Barneo et al. 1988; Thompson & Nurse, 2000). Also, the sympathetic neurones of the AM have not been reported to be oxygen sensors in the hypoxia range applied in our experiments. Thus, only blood and blood vessel cells, some of them known to respond to physiological hypoxia (Weir et al. 2002), might be obscuring the transcriptional changes of CB chemosensory cells. However, the analytical substraction of hypoxia-regulated genes from AM is expected to enrich the search by revealing genes involved in hypoxic transduction in CB cells.

Several laboratories have established that the effects on gene regulation upon environmental oxygen changes are associated with changes in the redox state of the cell. As an example, exposure to 10% O2 of a hypoxia-tolerant fish revealed, in several tissues, up-regulated genes such as lactate dehydrogenase A, enolase, triosephosphate isomerase, haeme-oxygenase-1, ferritin, transferrin, glucose-6-phosphatase, IGFBP-1, Erb-B2, and the MAP-kinase MKP-1 (Gracey et al. 2001). Similarly, both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of several genes have been demonstrated in oxygen-sensing cells (reviewed by Seta & Millhorn, 2004). Genes such as the angiogenic factor VEGF, the dopamine D2 receptor, the potassium channel Kvα1.2, the vascular endothelium EPAS-1 (HIF-2α), erythropoietin, c-fos, Bnip-3 and serpine1 are reported to be up-regulated by very low (1–2%) O2 levels (Premkumar et al. 2000; Seta & Millhorn, 2004). Many of these changes in expression are linked to the stabilization of the transcription factor HIF-1α, which organizes the early response to extreme decreases in O2 (reviewed by Sharp & Bernaudin, 2004). Also, NF-κB transcription and function is affected by oxygen, and thus by the intracellular redox state (reviewed by Haddad, 2004). A twofold change in TH expression is reached after 1 h exposure to 5% O2 in PC12 cells (Czyzyk-Krzeska et al. 1994). Also, moderate hypoxia levels (10% O2) up-regulate the CB transcription of TH (reviewed by Millhorn et al. 2000; Paulding et al. 2002).

Because of these studies, we searched our microarray CB data for changes in genes known to change their expression under hypoxia. We found consistent changes in the expression level under physiological hypoxia of: TH (1.84-fold increase), ferritin (2.16-fold increase), and triosephosphate isomerase (2.01-fold increase). A group of genes known to increase their transcription in response to hypoxia showed analogous but non-consistent changes in our CB microarray experiments. The genes c-fos, Bnip-3, serpine1, lactate dehydrogenase A, and MKP-1 have two I and one NC change calls in our experiments. However, the transcriptional regulation of these genes occurs under more extreme hypoxic conditions.

The ventilatory acclimation occurring under maintained and moderate hypoxia is associated with a sensitization of CB chemosensory cells. These processes participate in the physiological adaptation of organisms to high-altitude environments. Under these conditions, the CB experiences a hyperplasia due to an increase in the number and size of chemosensory cells (Arias-Stella & Valcarcel, 1976; Laidler & Kay, 1978). Moreover, an increase in expression of Na+ channels and connexin 43, as well as in neurotransmitter release and afferent discharges, are part of the response to sustained hypoxia (Gonzalez-Guerrero et al. 1993; Stea et al. 1995; Chen et al. 2002a).

In this context, and though our experiments are not designed to reveal transcriptional changes related to chronic hypoxia and CB hyperplasia, we looked for regulated genes of potential interest for understanding the process of hypoxic chemotransduction in the CB cells. We focused on two main groups: (i) neurotransmitters and neurotransmitter receptors that have been reported to contribute to the low- PO2 secretory response of the organ, and (ii) membrane ion channels that could participate in the early events of the hypoxic transduction cascade.

Given the prominent role of dopamine in the chemosensory process (Gonzalez et al. 1995), and the reported hypoxia regulation of the enzyme TH (see above), we searched for genes involved in the catecholamine metabolism. As mentioned, TH consistently increased its expression in our arrays, and we found a moderate decrease in expression of the noradrenaline synthesizing enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase. This suggests that physiological hypoxia favours the sustained presence of dopamine in the synaptic environment, where it functions as a neurotransmitter on afferent nerve endings. However, the dopamine D2 receptor, which has been reported to be up-regulated by hypoxia (Huey & Powell, 2000; Bairam et al. 2003), did not show expression changes under our hypoxia protocol.

The gene endothelin I (ET-1) enhances the excitability of and has a mitogenic effect on CB glomus cells under chronic hypoxia (10% O2), roles that have been ascribed to an up-regulation of the ET receptor A and ET-1 itself (Chen et al. 2002b, c). Our results show the presence in mouse normoxic CB of ET-1, and of ET-2 and the ET-receptor B at a lower level. However, none of these genes showed regulation upon 24 h of exposure to hypoxia. Notwithstanding, the ET converting enzyme (ECE-1), a zinc metalloprotease involved in the processing of endothelins to biologically active peptides, increases its expression (1.73-fold) under physiological hypoxia. We found a similar effect of hypoxia on angiotensin. This is in agreement with the local angiotensin functional system that has been reported in the chemosensory cells of the CB (reviewed by Leung et al. 2003), which is associated with up-regulation of angiotensin II receptors (AT1 type) upon chronic (7–28 days) hypoxia (Leung et al. 2000). Angiotensinogen and the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) are expressed in CB type I cells, and the ACE activity also increases under chronic hypoxia (Lam et al. 2004). Our microarray data reveal that ACE increases 1.87-fold specifically in mouse CB in response to 24 h of physiological hypoxia. Also, it is important to mention that these two genes (ECE-1 and ACE) are, in fact, switched-ON in our experiments (see Table 3).

The up-regulation by hypoxia of the enzymes carrying out the proteolytic processing of both ET-1 and angiotensin I suggests a hypoxia-mediated control process that would result in local high levels of active ET-1and angiotensin II in chemosensory cells. Of special interest for chemosensory transduction pathways is the common signalling pathway shared by ET-1 and angiotensin II, involving an IP3-mediated increase of [Ca2+]i that could enhance CB chemosensory cells excitability.

Serotonin generates a higher excitability in CB cells (reviewed by Bisgard, 2000) and is possibly involved in the transduction of the hypoxia stimulus. Our expression profile data reveal that serotonin receptors 1a, 3a, and 2c are expressed in mouse CB, and that the 5HT3a receptor expression is consistently down-regulated (1.55-fold) under 10% O2.

Adenosine receptor A2a is expressed in rat CB chemoreceptor cells (Gauda et al. 2000), and is up-regulated by chronic hypoxia in PC12 cells (Kobayashi et al. 2000). Our data show A2b to be present in normoxic mouse CB, in agreement with our experiments using A2b blockers (S. Conde, A. Obeso & C. González, unpublished observations). However, this receptor appears moderately down-regulated by 10%PO2 in our mouse arrays (two D and one NC change calls).

Also, CB cells show an up-regulation of VEGF and its receptor VEGFR-2 under chronic hypoxia in rat (Chen et al. 2003). Our array data show the presence of VEGF-C and the receptors VEGFR-1, 2, and 4 in normoxic CB. However, only the VEGFR-1 is up-regulated upon 24 h of physiological hypoxia, as is also the case for CB under chronic hypoxia (Tipoe & Fung, 2003).

Regarding the hypoxic regulation of membrane ion channels, our microarray data reveal the up-regulation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel Kir6.1 and the intermediate-conductance and Ca2+-activated K+ channel Kcnn4.

The up-regulation (1.65-fold) of Kir6.1 is in agreement with knockout mice experiments that have implicated this channel in responses to metabolic stress by hypoxia and glucose deprivation (Seino & Miki, 2004), its transcription being induced by hypoxia (Melamed-Frank et al. 2001). Kcnn4 has been reported as a marker for cellular proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells (Kohler et al. 2003). This role agrees with the consistent up-regulation (2.16-fold) we detect for Kcnn4 in CB subjected to hypoxia, which in turn could underlie the potent angiogenic effect produced by hypoxia on CB (reviewed by Fung, 2003).

Finally, we also found a consistent decrease (1.56-fold) in expression levels of the potassium channel modulatory subunit Kvβ1 (Kcnab1) by 10% O2. Kvβ associates with Kv1α subunits to induce fast inactivation in non-inactivating Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 channels, or to accelerate the fast inactivation of Kv1.4. Although these interactions were originally thought to be Kv1 subfamily-specific in heterologous systems, Kvβ subunits also interact with Kvα subunits in other subfamilies (Aimond et al. 2005). The data currently available regarding the functional role of Kcnab1 obtained from knock-out mice are contradictory: while Kcnab1-deficient mice show alterations in the firing discharges of hipoccampal neurones due to a reduction in the proportion of fast inactivating current (Giese et al. 1998), targeted disruption of Kcnab1 in myocardial cells results in a decreased membrane expression of Kv4.3 channels and increased membrane expression of Kv2.1 channels without altering Kv1 subunit-encoded currents (Aimond et al. 2005). Clearly, in order to infer the functional role of its hypoxic down-regulation in our preparation, we will need to study the partners of Kcnab1 in CB cells and their cellular location. However, this down-regulation by sustained hypoxia, together with the fact that Kvb1.2 has been reported to confer oxygen sensitivity to Kv4.2 channels in heterologous systems (Perez-Garcia et al. 1999), could reflect an important role of this gene in the regulation of hypoxic sensitivity.

These findings differ from those of our recent report (Perez-Garcia et al. 2004) demonstrating the expression of Kv2 and Kv3 subfamilies in mouse CB chemoreceptor cells, and the modulation of Kv3 by acute hypoxic exposure. Several Kv2 and Kv3 subfamily members were detected in our CB arrays in normoxia, but we found no changes in their expression in response to physiological sustained hypoxia. These results suggest that different sets of channels are transducing the response of CB chemoreceptor cells upon acute versus sustained hypoxia, as we have recently documented for rabbit CB glomus cells (Kääb et al. 2005).

In summary, we present the first reported transcriptional profile of mouse CB in response to physiological sustained hypoxia. An interesting finding of our work is the fact that many of the genes we have identified as hypoxia regulated in CB are, in fact, functionally related to molecules known to be released by type I cells upon low O2 stimulation (see Supplemental material). These results also suggest that given our whole-organ approach and the long-term hypoxia exposure used, our microarray experiments are identifying not only the genes directly regulated by oxygen, but other genes regulated by molecules released as a consequence of CB activation. Obviously, these genes can be present both in type I cells and vascular vessels, but the subtractive approach followed in the analysis suggests that their regulation is CB specific and that those genes present in vascular cells are changing their expression as a consequence of paracrine factors released by type I cells in response to physiological hypoxia. Additionally, our results identify a new group of CB ion channels experiencing transcriptional changes under hypoxia. The expression of these channels needs to be demonstrated in chemosensory cells, but their regulation after the analytical subtraction from other hypoxia-exposed tissues suggests they are present in CB neural cells.

The data generated in this analysis will lead to future testing of the role of the candidate genes using neurochemical and electrophysiological experiments at the cellular level. In addition, these experiments could exploit the potential of the mouse model system by using mice carrying mutations that will alter their expression or function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a JCyL grant VA037/03 to D.S. Additional support came from the following agencies: Start-up grants to D.S and M.D.G. from the Ramón y Cajal Program (MEC); MEC grant BFU2004-06394/BFI to C.G.; DGICYT grant BFU2004-05551 to M.T.P.G; Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant G03/011 (Red Respira) to C.G.; Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant G03/045 (Red Heracles), and DGICYT grant BFU2001-1691 to J.R.L.L; MCyT grant TIC2003-09331-CO2-01. We thank Dr E. Fermiñan, of the Genomics Facility of the Centro de Investigación del Cáncer (Salamanca) for technical assistance and advice. We also thank E. Alonso for technical help with qRT-PCR.

Supplemental material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088815 http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2005.088815/DC1 and contains supplementalmaterial showing other interaction networks among CB genes regulated under hypoxia.

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Aimond F, Kwak SP, Rhodes KJ, Nerbonne JM. Accessory Kvβ1 subunits differentially modulate the functional expression of voltage-gated K+ channels in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2005;96:451–458. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156890.25876.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahrour F, Diaz-Uriarte R, Dopazo J. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:578–580. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravindan N, Williams MT, Riedel BJ, Shaw AD. Transcriptional responses of rat skeletal muscle following hypoxia-reoxygenation and near ischaemia-reperfusion. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183:367–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2005.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Stella J, Valcarcel J. Chief cell hyperplasia in the human carotid body at high altitudes; physiologic and pathologic significance. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:361–373. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(76)80052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairam A, Lajeunesse Y, Joseph V, Labelle Y. Time dependent regulation of dopamine D1- and D2-receptor gene expression in the carotid body of developing rabbits by hypoxia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;536:541–547. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9280-2_68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Seta K, Yuan Y, Kim H, Rust RT, Conrad PW, Kobayashi S, Millhorn DE. Identification of hypoxia-responsive genes in a dopaminergic cell line by subtractive cDNA libraries and microarray analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2001;7:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(00)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE. Carotid body mechanisms in acclimatization to hypoxia. Respir Physiol. 2000;121:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Dinger B, Jyung R, Stensaas L, Fidone S. Altered expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and FLK-1 receptor in chronically hypoxic rat carotid body. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;536:583–591. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9280-2_74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, He L, Dinger B, Stensaas L, Fidone S. Chronic hypoxia upregulates connexin43 expression in rat carotid body and petrosal ganglion. J Appl Physiol. 2002a;92:1480–1486. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00077.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, He L, Dinger B, Stensaas L, Fidone S. Role of endothelin and endothelin A-type receptor in adaptation of the carotid body to chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002b;282:L1314–L1323. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00454.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tipoe GL, Liong E, Leung S, Lam SY, Iwase R, Tjong YW, Fung ML. Chronic hypoxia enhances endothelin-1-induced intracellular calcium elevation in rat carotid body chemoreceptors and up-regulates ETA receptor expression. Pflugers Arch. 2002c;443:565–573. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Bayliss DA, Lawson EE, Millhorn DE. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the rat carotid body by hypoxia. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1538–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Furnari BA, Lawson EE, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia increases rate of transcription and stability of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:760–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Yeh H, Miyashiro K, Cao Y, Nair S, Finnell R, Zettel M, Coleman P. Analysis of gene expression in single live neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung ML. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1: a molecular hint of physiological changes in the carotid body during long-term hypoxemia? Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2003;3:254–259. doi: 10.2174/1568006033481447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauda EB, Northington FJ, Linden J, Rosin DL. Differential expression of A2a, A1-adenosine and D2-dopamine receptor genes in rat peripheral arterial chemoreceptors during postnatal development. Brain Res. 2000;872:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese KP, Storm JF, Reuter D, Fedorov NB, Shao LR, Leicher T, Pongs O, Silva AJ. Reduced K+ channel inactivation, spike broadening, and after-hyperpolarization in Kvβ1.1-deficient mice with impaired learning. Learn Mem. 1998;5:257–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert RW, Costain WJ, Blanchard ME, Mullen KL, Currie RW, Robertson HA. DNA microarray analysis of hippocampal gene expression measured twelve hours after hypoxia-ischemia in the mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1195–1211. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000088763.02615.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C. Sensitivity to physiologic hypoxia. In: Lopez-Barneo J, Weir EK, editors. Oxygen Regulation of Ion Channels and Gene Expression. Armonk, NY, USA: Futura Publishing Co; 1998. pp. 321–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:829–898. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Lopez-Lopez JR, Obeso A, Perez-Garcia MT, Rocher A. Cellular mechanisms of oxygen chemoreception in the carotid body. Respir Physiol. 1995;102:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Rocher A, Zapata P. Arterial chemoreceptors: cellular and molecular mechanisms in the adaptative and homeostatic function of the carotid body. Rev Neurol. 2003;36:239–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guerrero PR, Rigual R, Gonzalez C. Effects of chronic hypoxia on opioid peptide and catecholamine levels and on the release of dopamine in the rabbit carotid body. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1769–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracey AY, Troll JV, Somero GN. Hypoxia-induced gene expression profiling in the euryoxic fish Gillichthys mirabilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1993–1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad JJ. Oxygen sensing and oxidant/redox-related pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:969–977. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshikawa Y, Nana-Sinkam P, Moore MD, Sotto-Santiago S, Phang T, Keith RL, Morris KG, Kondo T, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Geraci MW. Hypoxia induces different genes in the lungs of rats compared with mice. Physiol Genomics. 2003;12:209–219. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00081.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey KA, Powell FL. Time-dependent changes in dopamine D2-receptor mRNA in the arterial chemoreflex pathway with chronic hypoxia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;75:264–270. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kääb S, Miguel-Velado E, Lopez-Lopez JR, Perez-Gaiúa MT. Down regulation of kv 3.4 channels by chronic hypoxia increases acute oxygen sensitivity in rabbit carotid body. J. Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085837. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen S, Workman C, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Friis C. GenePublisher: Automated analysis of DNA microarray data. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:3471–3476. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Conforti L, Millhorn DE. Gene expression and function of adenosine A2A receptor in the rat carotid body. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L273–L282. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.2.L273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R, Wulff H, Eichler I, Kneifel M, Neumann D, Knorr A, Grgic I, Kampfe D, Si H, Wibawa J, Real R, Borner K, Brakemeier S, Orzechowski HD, Reusch HP, Paul M, Chandy KG, Hoyer J. Blockade of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel as a new therapeutic strategy for restenosis. Circulation. 2003;108:1119–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086464.04719.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T, Kimura N, Miyazaki K, Yabuta T, Kumamoto K, Takenoshita S, Chen J, Kobayashi M, Hosokawa M, Taniguchi A, Kojima T, Ishida N, Kawakita M, Yamamoto H, Takematsu H, Suzuki A, Kozutsumi Y, Kannagi R. Hypoxia induces adhesion molecules on cancer cells: a missing link between Warburg effect and induction of selectin-ligand carbohydrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidler P, Kay JM. A quantitative study of some ultrastructural features of the type I cells in the carotid bodies of rats living at a simulated altitude of 4300 metres. J Neurocytol. 1978;7:183–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01217917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SY, Fung ML, Leung PS. Regulation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme activity by a time-course hypoxia in the carotid body. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:809–813. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00684.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PS, Fung ML, Tam MS. Renin-angiotensin system in the carotid body. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:847–854. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PS, Lam SY, Fung ML. Chronic hypoxia upregulates the expression and function of AT1 receptor in rat carotid body. J Endocrinol. 2000;167:517–524. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1670517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barneo J, Lopez-Lopez JR, Urena J, Gonzalez C. Chemotransduction in the carotid body: K+ current modulated by PO2 in type I chemoreceptor cells. Science. 1988;241:580–582. doi: 10.1126/science.2456613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed-Frank M, Terzic A, Carrasco AJ, Nevo E, Avivi A, Levy AP. Reciprocal regulation of expression of pore-forming KATP channel genes by hypoxia. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;225:145–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1012286624993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhorn DE, Beitner-Johnson D, Conforti L, Conrad PW, Kobayashi S, Yuan Y, Rust R. Gene regulation during hypoxia in excitable oxygen-sensing cells: depolarization-transcription coupling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:131–142. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulding WR, Schnell PO, Bauer AL, Striet JB, Nash JA, Kuznetsova AV, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Regulation of gene expression for neurotransmitters during adaptation to hypoxia in oxygen-sensitive neuroendocrine cells. Hypoxia-induced regulation of mRNA stability. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:178–187. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C. Interactions of chemostimuli at the single cell level: studies in a model system. Exp Physiol. 2004;89:60–65. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2003.002657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia MT, Colinas O, Miguel-Velado E, Moreno-Dominguez A, Lopez-Lopez JR. Characterization of the Kv channels of mouse carotid body chemoreceptor cells and their role in oxygen sensing. J Physiol. 2004;557:457–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia MT, Lopez-Lopez JR, Gonzalez C. Kvβ1.2 subunit coexpression in HEK293 cells confers O2 sensitivity to kv4.2 but not to Shaker channels. J General Physiol. 1999;113:897–907. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.6.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing by the carotid body chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:2287–2295. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing during intermittent hypoxia: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1986–1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Adhikary G, Overholt JL, Simonson MS, Cherniack NS, Prabhakar NR. Intracellular pathways linking hypoxia to activation of c-fos and AP-1. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:101–109. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Identifying differentially expressed genes using false discovery rate controlling procedures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S, Miki T. Gene targeting approach to clarification of ion channel function: studies of Kir6.x null mice. J Physiol. 2004;554:295–300. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seta KA, Millhorn DE. Functional genomics approach to hypoxia signaling. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:765–773. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00836.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Bernaudin M. HIF1 and oxygen sensing in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington C. The Integrative Action of the Nervous System. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. Adrenomedullary catecholamine release in the fetus and newborn: secretory mechanisms and their role in stress and survival. J Dev Physiol. 1988;10:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Jackson A, Macintyre L, Nurse CA. Long-term modulation of inward currents in O2 chemoreceptors by chronic hypoxia and cyclic AMP in vitro. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2192–2202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02192.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Nurse CA. O2-chemosensitivity in developing rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:601–609. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipoe GL, Fung ML. Expression of HIF-1α, VEGF and VEGF receptors in the carotid body of chronically hypoxic rat. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;138:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir EK, Hong Z, Porter VA, Reeve HL. Redox signaling in oxygen sensing by vessels. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;132:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Simons JW. Direct comparison of GAPDH, β-actin, cyclophilin, and 28S rRNA as internal standards for quantifying RNA levels under hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:523–526. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.