Abstract

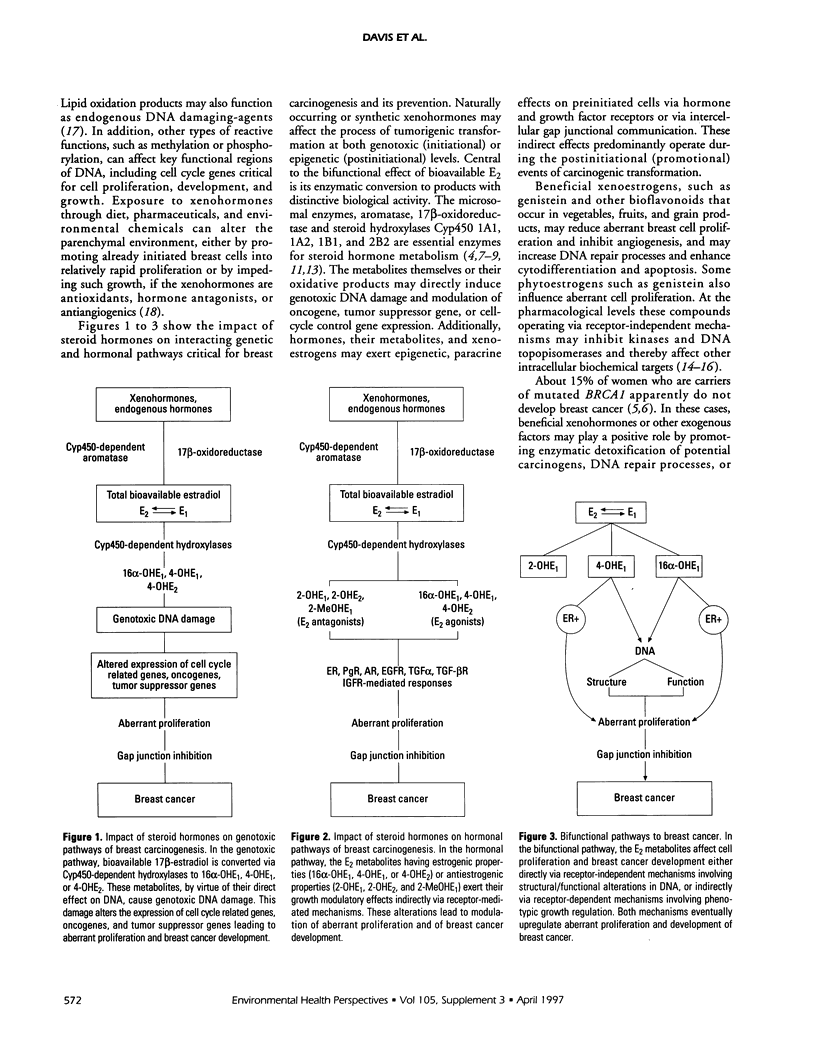

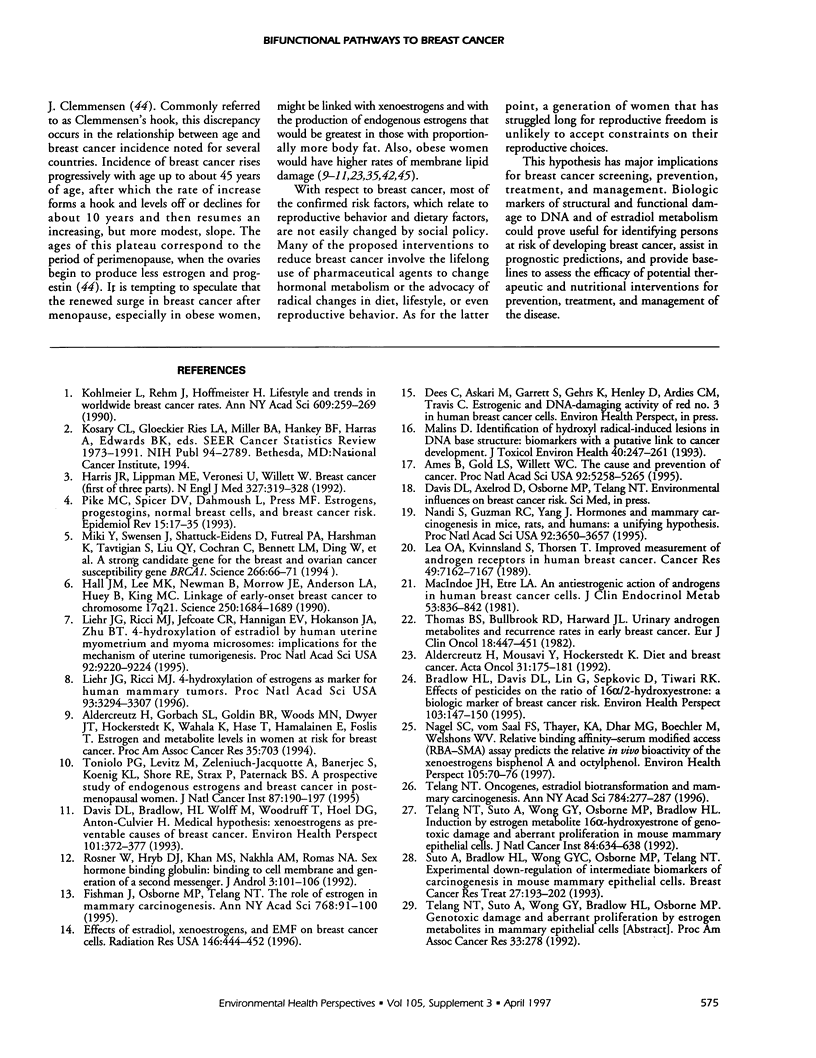

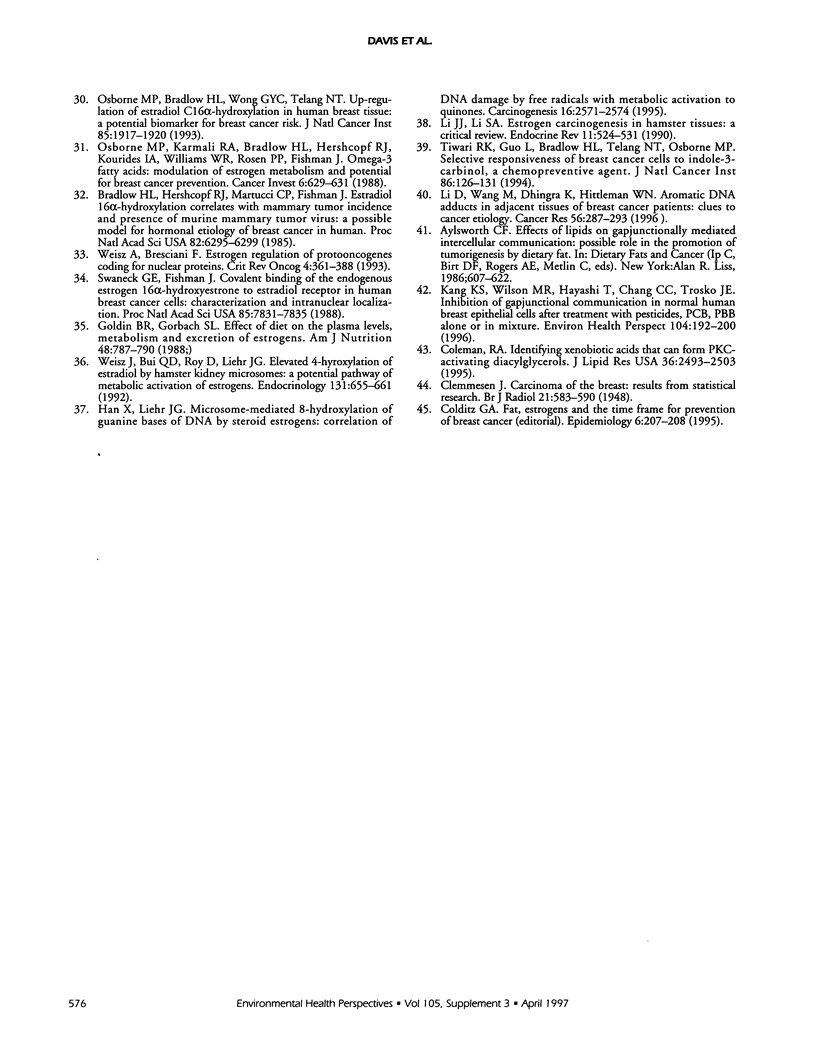

As inherited germ line mutations, such as loss of BRCA1 or AT, account for less than 5% of all breast cancer, most cases involve acquired somatic perturbations. Cumulative lifetime exposure to bioavailable estradiol links most known risk factors (except radiation) for breast cancer. Based on a series of recent experimental and epidemiologic findings, we hypothesize that the multistep process of breast carcinogenesis results from exposure to endogenous or exogenous hormones, including phytoestrogens that directly or indirectly alter estrogen metabolism. Xenohormones are defined as xenobiotic materials that modify hormonal production; they can work bifunctionally, through genetic or hormonal paths, depending on the periods and extent of exposure. As for genetic paths, xenohormones can modify DNA structure or function. As for hormonal paths, two distinct mechanisms can influence the potential for aberrant cell growth: compounds can directly bind with endogenous hormone or growth factor receptors affecting cell proliferation or compounds can modify breast cell proliferation altering the formation of hormone metabolites that influence epithelial-stromal interaction and growth regulation. Beneficial xenohormones, such as indole-3-carbinol, genistein, and other bioflavonoids, may reduce aberrant breast cell proliferation, and influence the rate of DNA repair or apoptosis and thereby influence the genetic or hormonal microenvironments. Upon validation with appropriate in vitro and in vivo studies, biologic markers of the risk for breast cancer, such as hormone metabolites, total bioavailable estradiol, and free radical generators can enhance cancer detection and prevention.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adlercreutz H., Mousavi Y., Höckerstedt K. Diet and breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1992;31(2):175–181. doi: 10.3109/02841869209088899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B. N., Gold L. S., Willett W. C. The causes and prevention of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Jun 6;92(12):5258–5265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylsworth C. F. Effects of lipids on gap junctionally-mediated intercellular communication: possible role in the promotion of tumorigenesis by dietary fat. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1986;222:607–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow H. L., Davis D. L., Lin G., Sepkovic D., Tiwari R. Effects of pesticides on the ratio of 16 alpha/2-hydroxyestrone: a biologic marker of breast cancer risk. Environ Health Perspect. 1995 Oct;103 (Suppl 7):147–150. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow H. L., Hershcopf R. J., Martucci C. P., Fishman J. Estradiol 16 alpha-hydroxylation in the mouse correlates with mammary tumor incidence and presence of murine mammary tumor virus: a possible model for the hormonal etiology of breast cancer in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Sep;82(18):6295–6299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. L., Bradlow H. L., Wolff M., Woodruff T., Hoel D. G., Anton-Culver H. Medical hypothesis: xenoestrogens as preventable causes of breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1993 Oct;101(5):372–377. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P. F., Chou S. C., Ranasinghe A., Coleman R. A. Metabolism of fenbufen by cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes: synthesis and metabolism of xenobiotic glycerolipids. J Lipid Res. 1995 Dec;36(12):2493–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman J., Osborne M. P., Telang N. T. The role of estrogen in mammary carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995 Sep 30;768:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb12113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin B. R., Gorbach S. L. Effect of diet on the plasma levels, metabolism, and excretion of estrogens. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Sep;48(3 Suppl):787–790. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. M., Lee M. K., Newman B., Morrow J. E., Anderson L. A., Huey B., King M. C. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990 Dec 21;250(4988):1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Liehr J. G. Microsome-mediated 8-hydroxylation of guanine bases of DNA by steroid estrogens: correlation of DNA damage by free radicals with metabolic activation to quinones. Carcinogenesis. 1995 Oct;16(10):2571–2574. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.10.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. R., Lippman M. E., Veronesi U., Willett W. Breast cancer (1) N Engl J Med. 1992 Jul 30;327(5):319–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207303270505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. S., Wilson M. R., Hayashi T., Chang C. C., Trosko J. E. Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication in normal human breast epithelial cells after treatment with pesticides, PCBs, and PBBs, alone or in mixtures. Environ Health Perspect. 1996 Feb;104(2):192–200. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeier L., Rehm J., Hoffmeister H. Lifestyle and trends in worldwide breast cancer rates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;609:259–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb32073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea O. A., Kvinnsland S., Thorsen T. Improved measurement of androgen receptors in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1989 Dec 15;49(24 Pt 1):7162–7167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Wang M., Dhingra K., Hittelman W. N. Aromatic DNA adducts in adjacent tissues of breast cancer patients: clues to breast cancer etiology. Cancer Res. 1996 Jan 15;56(2):287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J., Li S. A. Estrogen carcinogenesis in hamster tissues: a critical review. Endocr Rev. 1990 Nov;11(4):524–531. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-4-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr J. G., Ricci M. J. 4-Hydroxylation of estrogens as marker of human mammary tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Apr 16;93(8):3294–3296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr J. G., Ricci M. J., Jefcoate C. R., Hannigan E. V., Hokanson J. A., Zhu B. T. 4-Hydroxylation of estradiol by human uterine myometrium and myoma microsomes: implications for the mechanism of uterine tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Sep 26;92(20):9220–9224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIndoe J. H., Etre L. A. An antiestrogenic action of androgens in human breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981 Oct;53(4):836–842. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-4-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malins D. C. Identification of hydroxyl radical-induced lesions in DNA base structure: biomarkers with a putative link to cancer development. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1993 Oct-Nov;40(2-3):247–261. doi: 10.1080/15287399309531792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y., Swensen J., Shattuck-Eidens D., Futreal P. A., Harshman K., Tavtigian S., Liu Q., Cochran C., Bennett L. M., Ding W. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994 Oct 7;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel S. C., vom Saal F. S., Thayer K. A., Dhar M. G., Boechler M., Welshons W. V. Relative binding affinity-serum modified access (RBA-SMA) assay predicts the relative in vivo bioactivity of the xenoestrogens bisphenol A and octylphenol. Environ Health Perspect. 1997 Jan;105(1):70–76. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9710570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi S., Guzman R. C., Yang J. Hormones and mammary carcinogenesis in mice, rats, and humans: a unifying hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Apr 25;92(9):3650–3657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne M. P., Bradlow H. L., Wong G. Y., Telang N. T. Upregulation of estradiol C16 alpha-hydroxylation in human breast tissue: a potential biomarker of breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Dec 1;85(23):1917–1920. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike M. C., Spicer D. V., Dahmoush L., Press M. F. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):17–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W., Hryb D. J., Khan M. S., Nakhla A. M., Romas N. A. Sex hormone-binding globulin. Binding to cell membranes and generation of a second messenger. J Androl. 1992 Mar-Apr;13(2):101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto A., Bradlow H. L., Wong G. Y., Osborne M. P., Telang N. T. Experimental down-regulation of intermediate biomarkers of carcinogenesis in mouse mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993 Sep;27(3):193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00665689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaneck G. E., Fishman J. Covalent binding of the endogenous estrogen 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone to estradiol receptor in human breast cancer cells: characterization and intranuclear localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Nov;85(21):7831–7835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telang N. T. Oncogenes, estradiol biotransformation, and mammary carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996 Apr 30;784:277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb16242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telang N. T., Suto A., Wong G. Y., Osborne M. P., Bradlow H. L. Induction by estrogen metabolite 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone of genotoxic damage and aberrant proliferation in mouse mammary epithelial cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992 Apr 15;84(8):634–638. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B. S., Bulbrook R. D., Hayward J. L., Millis R. R. Urinary androgen metabolites and recurrence rates in early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1982 May;18(5):447–451. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(82)90112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari R. K., Guo L., Bradlow H. L., Telang N. T., Osborne M. P. Selective responsiveness of human breast cancer cells to indole-3-carbinol, a chemopreventive agent. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994 Jan 19;86(2):126–131. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toniolo P. G., Levitz M., Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A., Banerjee S., Koenig K. L., Shore R. E., Strax P., Pasternack B. S. A prospective study of endogenous estrogens and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Feb 1;87(3):190–197. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke J. P. How much of the cardioprotective effect of postmenopausal estrogens is real? Epidemiology. 1995 May;6(3):207–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz A., Bresciani F. Estrogen regulation of proto-oncogenes coding for nuclear proteins. Crit Rev Oncog. 1993;4(4):361–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J., Bui Q. D., Roy D., Liehr J. G. Elevated 4-hydroxylation of estradiol by hamster kidney microsomes: a potential pathway of metabolic activation of estrogens. Endocrinology. 1992 Aug;131(2):655–661. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1386303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]