Abstract

Structural and dynamic properties of a partially folded conformation (A-state) of ubiquitin are studied using amide hydrogen exchange in solution (HDX) and mass spectrometric detection. A clear distinction between the native state of the protein and the A-state can be made when HDX is carried out in a semi-correlated regime. Convoluted exchange patterns are interpreted with the aid of HDX simulations in a three-state system (highly structured-partially unstructured-fully unstructured states). The data clearly indicate a highly dynamic character of the non-native state. Furthermore, combination of HDX and protein ion fragmentation in the gas phase (by means of collision-induced dissociation, CAD) is used to evaluate conformational stability of various protein segments specifically in the molten globular state. Chain flexibility appears to be distributed very unevenly in this non-native conformation. The highest degree of structural disorder is displayed by the C-terminal segment (Gly53→Gly76), which was previously suggested to form a transient α-helix. The least dynamic segment of ubiquitin in the A-state is Thr9→Glu18 (which was previously suggested to form a stable native-like β-strand), with the adjacent segments exhibiting somewhat diminished conformational stability. The study also demonstrates the power of mass spectrometry as a tool to provide conformer-specific information on structure and dynamics of both native and non-native protein states co-existing in solution under equilibrium.

Keywords: protein dynamics; protein unfolding; protein conformation; equilibrium states; energy landscapes; molten globule; hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX); mass spectrometry (MS); electrospray ionization (ESI); fragmentation, protein ion; collision-activated dissociation (CAD); Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT ICR MS)

Molten globule is a term that is often used to describe a class of compact non-native protein states that are often thought to be general intermediates in protein folding, which are characterized by a substantial degree of secondary structure and nearly total absence of a native tertiary fold (1). Extensive studies of molten globular states of a variety of proteins were initially catalyzed by the realization that elucidating their structural and dynamic features may provide important clues for solving the protein folding problem (2, 3). Since the kinetic folding intermediates are populated only transiently during the protein folding process, properties of molten globular states are often studied using the equilibrium models. In fact, it is the partially unfolded equilibrium intermediates that were initially proposed to belong to a common physical state of globular proteins, for which the term molten globular state was coined. More recently, renewed interest in properties and behavior of molten globular states was instigated by a growing understanding that structural disorder is quite ubiquitous in vivo and often plays an important role in a variety of physiological processes (4). Such partially unstructured protein states have been implicated in a variety of processes ranging from protein translocation through membranes to ordered oligomerization, recognition, signaling and even catalysis.

The experimental tools employed in the studies of molten globular states include circular dichroism spectroscopy and calorimetric characterization, with NMR and small-angle X-ray scattering rapidly gaining popularity in this field as well. A major difficulty associated with the experimental studies of the molten globular states under equilibrium conditions is due to the impossibility to force the entire ensemble of protein molecules to the molten globular state. Indeed, while the molten globular state is separated from the native state by a highly-cooperative first-order phase transition, a collapse of random coil to the molten globule should be a second-order transition and, therefore, lack cooperativity (5). As pointed out by Privalov, a continuous distribution of microstates becomes populated at equilibrium in the case of a second-order transition, which is manifested kinetically as a gradual (non-cooperative) transformation of the macroscopic states (5). It is the significant degree of structural heterogeneity and dynamic character of the molten globular state that often make its detailed structural characterization difficult (6). Mass spectrometry has emerged in the past decade as a powerful alternative tool to study structural and dynamic properties of biopolymers (7). One particularly attractive experimental technique is hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) used in combination with mass spectrometric detection (8, 9), which in many cases provides a unique opportunity to detect and characterize protein dynamics in a conformer-specific fashion (10, 11). Such state-specific characterization becomes possible only in the so-called correlated exchange regime, in which a group of backbone amides become solvent-exposed simultaneously upon transition from a more structured state to a less structured one, while the intrinsic exchange rate of the exposed amides is high enough to afford labeling of this entire group during a single opening event (a condition commonly referred to as EX1 mechanism (10)). Furthermore, combination of HDX in solution and protein ion fragmentation (by means of collision-induced dissociation, CAD) in the gas phase allows the dynamic events to be probed in a segment-specific fashion (12).

HDX MS has been used in the past by several groups to study behavior of molten globules at equilibrium (13, 14), although the experiments were typically carried out under conditions that prevent distinct detection of different proteins states. Indeed, molten globular states of many proteins are known to be favored in acidic solutions, where the intrinsic exchange rates of unprotected amides is decreased very dramatically (15). Low intrinsic exchange rates typically cause HDX to follow the so-called EX2 exchange regime (16), which always results in uncorrelated HDX MS patterns, hence the inability to track protein behavior in a conformer-specific fashion. A recent attempt to characterize a molten globular state of creatine kinase by HDX MS under conditions favoring EX1 exchange regime has failed to detect any measurable protection against the exchange (17). Such apparent lack of protection (despite significant helical content) was interpreted in terms of a highly dynamic character attributed to this state in the absence of stabilizing tertiary contacts.

Structural fluidity is indeed considered one of the general characteristics of molten globular states, however there are several well-documented examples when a certain segment of a protein does maintain a more or less stable structure. In particular, the methanol-induced A-state of a small protein ubiquitin was shown to retain a significant proportion of its native tertiary structure in the N-terminal segment, which was stable enough to allow the 1H-1H nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) to be observed in NMR spectra (18). Interestingly, the C-terminal part of ubiquitin was found to be highly dynamic, despite a uniformly high propensity for non-native helical structure. This finding contradicted earlier studies of the same protein, which concluded that the C-terminal part largely retained a native-like format (19). The conflicting views of the structure of ubiquitin A-state may be caused in part by interference of both native and fully denatured state of this protein with the measurements of properties of a partially folded molten globular state. Indeed, solution conditions that are typically used to populate the A-state (low salt, pH 2, 60% methanol by volume) do not result in complete elimination of other states of ubiquitin. In fact, both natively folded and fully unfolded protein states are present in solution in considerable amounts under these conditions, as suggested by the analysis of charge state distribution of ubiquitin ions in electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra (20). It is one of the goals of this work to assess the utility of HDX MS as a means of obtaining both structural and dynamic characteristics of a molten globular state. This is accomplished by carrying out the experiments under conditions favoring the EX1 exchange regime, which allows the distinction to be made between the native and non-native states of ubiquitin. Uncorrelated and rapid (but measurable) loss of 2H content in the A-state is ascribed to the fact that its transition to the random coil state is a second-order transition. Finally, a combination of HDX in solution and protein ion fragmentation in the gas phase allows us to localize a stable core of the A-state, which appears to comprise a significant segment of the N-terminal half of the protein (forming a β-strand and an internal α-helix in the native form of ubiquitin).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials. Ubiquitin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and was used without further purification. Deuterium oxide (99% 2H) and d4-acetic acid were purchased from Cambride Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade or higher.

HDX MS and HDX CAD MS measurements. Complete deuteration of ubiquitin prior to HDX experiments was achieved by incubating the denatured protein in 2H2O at pD 2 (unadjusted for the isotope effect) and 45°C for 1 h followed by lyophilization. This procedure was repeated at least three times to ensure complete replacement of all labile hydrogen atoms with 2H (completeness of protein deuteration was also verified by ESI MS). The pD of the final stock solution of deuterated ubiquitin in 2H2O was adjusted to 6.8 using d4-acetic acid. HDX MS measurements were performed on an Apex III (Bruker Daltonics, Inc., Billerica, MA) FT ICR mass spectrometer equipped with a standard ESI source and a 4.7T actively shielded magnet. HDX reactions were initiated by diluting an aliquot of the 350 μM solution of deuterated ubiquitin in 10mM ammonium acetate solution (pH 6.8) at a 1:50 ratio (v/v). Collision-activated dissociation (CAD) of protein ions was achieved by increasing the capillary-exit potential from 90 V to 300 V and increasing the hexapole accumulation time from 0.5 sec to 1 sec. Eight scans (with a total acquisition time of ca. 45 sec) were averaged to record each CAD spectrum to insure adequate signal-to-noise ratio. Calculations of the distributions of deuterium content within various protein segments were carried out using a deconvolution procedure developed in our laboratory.

HDX MS simulation. Simulation of HDX MS patterns for a three-state protein was carried out by extending the model, which was initially developed for a two-state protein and is described in detail elsewhere (11) (see the Supporting Information section for more detail).

RESULTS

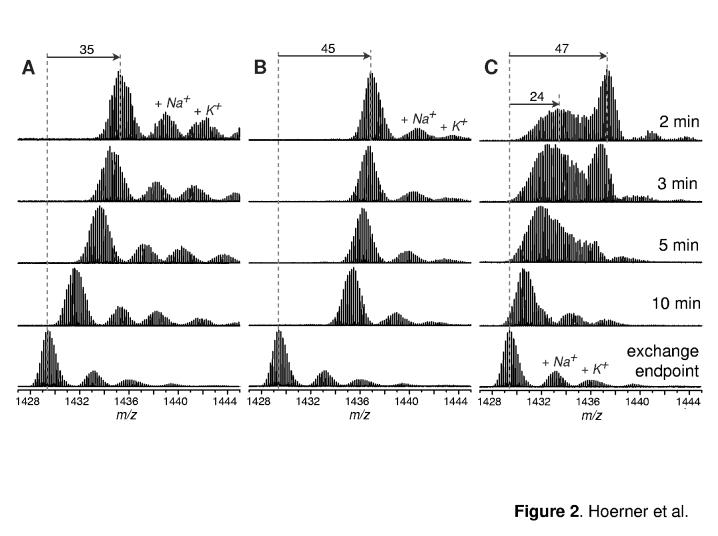

HDX MS patterns: global dynamics of ubiquitin under non-native conditions. The A-state of ubiquitin is typically induced by acidification of the protein solution to pH 2 under low salt conditions and in the presence of alcohol (60% by volume) (18). Amide exchange of Ub under such conditions is clearly uncorrelated, as suggested by the appearance of isotopic distributions of protein ions in ESI mass spectra (Figure 2A). Although the appearance of HDX MS profiles under these conditions is qualitatively similar to those observed under native conditions (Figure 2B), significant destabilization of Ub at pH 2 and high alcohol content can be inferred indirectly by comparing the two sets of spectra. Indeed, the exchange occurs much faster under acidic conditions, despite a dramatic decrease of the intrinsic exchange rate (over three orders of magnitude). The difference in exchange kinetics was used in the past to study dynamics of non-native protein states. For example, Deinzer and co-workers studied acid-induced intermediate states of cytochrome c at low pH and noticed that HDX MS can provide indirect information on various non-native protein states by comparing the exchange kinetics at neutral and acidic pH (13). However, the uncorrelated character of the exchange reactions does not allow different protein states to be detected directly, even though they are significantly populated under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Evolution of isotopic distributions of intact Ub ions (charge state +6) throughout the course of hydrogen exchange in solution initiated by diluting a deuterated protein solution in protiated exchange buffer at pH 2, 60% MeOH (A); pH 7, 0% MeOH (B); and pH 7, 60% MeOH (C).

Since the major goal of the present work was direct observation and characterization of the A-state of Ub, we have examined a range of mildly denaturing conditions, which may favor correlated or semi-correlated exchange. Correlated exchange patterns can only be observed when HDX follows EX1 mechanism (i.e., intrinsic exchange rate exceeds protein refolding rate) (10, 11). Since the acid catalysis of amide exchange reactions is much less efficient than the base catalysis (15), the EX1 exchange regime is typically achieved when HDX measurements are carried out at elevated pH. The results of our previous work indicate that a partially structured non-native state of Ub becomes populated at neutral pH upon addition of alcohol to the protein solution at a level exceeding 40% by volume (20). A detailed analysis of charge state distributions of Ub ions in electrospray ionization mass spectra under these conditions indicated that this non-native state displays the same degree of compactness as the A-state of the protein (which was determined to be the principal, although not the only, Ub species at pH 2, 60% methanol).

While the exchange under these conditions is relatively fast and is usually completed within less than one hour, the recorded mass spectra clearly show bimodal isotopic distributions during first ten minutes of exchange in solution (Figure 2C). We note, however, that we have not been able to observe fully correlated exchange, a pattern exhibited by small two-state proteins under similar conditions (11). Instead, the isotopic envelop corresponding to the less protected protein species indicates some residual protection, which is gradually lost (notice a continuous shift of this envelop towards the lower m/z values in Figure 2C). While similar semi-correlated exchange patterns can in fact be displayed by two-state proteins (an intermediate exchange regime identified as EXX), it only occurs within a narrow range of conditions separating EX1 and EX2 exchange regimes (11). The persistence of the semi-correlated exchange pattern in the case of Ub at high pH is surprising and will be discussed in the following sections.

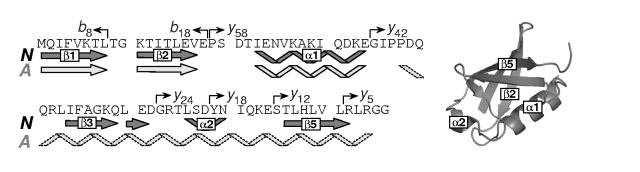

HDX CAD MS patterns: local dynamics of ubiquitin under non-native conditions. HDX MS measurements described in the previous paragraph provide information on the global dynamics of the protein in a state-specific fashion. Local information can be obtained by introducing a protein fragmentation step prior to MS detection. This can be done either proteolytically under slow exchange conditions in solution (21) or by inducing protein ion fragmentation in the gas phase (12). The latter offers an advantage of much shorter data acquisition times and also avoids problems associated with back exchange, although it may in some instances suffer from the limitations imposed by internal hydrogen exchange in the gas phase prior to the dissociation event (the so-called hydrogen scrambling). In this work we used collision-activated dissociation (CAD) of protein ions in the ESI interface region, which has been shown before to minimize hydrogen scrambling (12, 22), in order to obtain segment-specific information on deuterium retention by different states of the protein. Overall, over 32 fragment ions have been detected, although only eight most abundant ones (b8+, b182+, y585+, y424+, y242+, y182+, y122+, and y5+) were used to characterize structure and dynamics of the non-native state of Ub. This set of fragment ions provides fairly even coverage of the protein sequence with segments ranging in length from seven to eighteen amino acid residues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence and secondary structure of natively folded ubiquitin. Previously postulated secondary structure of the A-state (18, 26) is shown in a lighter shade of gray. The diagram on the right represents the tertiary fold of native ubiquitin. Arrows indicate positions of ubiquitin fragment ions discussed in the text.

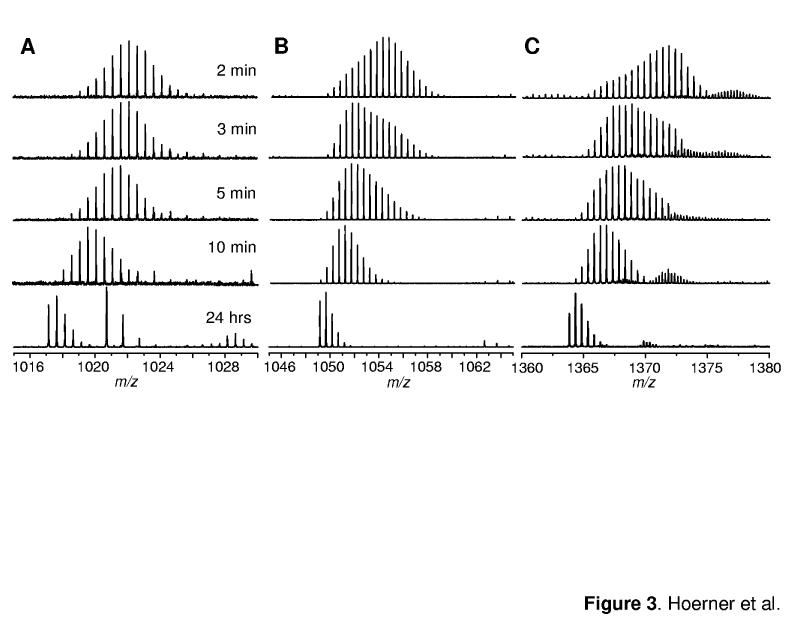

Even a simple comparison of evolution of the isotopic distributions of y- and b-ions provides clear indication of how different the dynamic behavior of various segments of Ub is (e.g., compare the isotopic distributions of b182+ and y182+ fragment ions in Figure 3A and B). Accurate calculations of the isotopic content of any protein segment flanked by two fragment ions require that the actual isotopic distribution of the two fragments, rather than their average deuterium content, be taken into consideration. For example, deuterium content of the [Gly53→Asp58] segment can be deconvoluted from the experimentally measured isotopic distributions of y242+ and y182+ fragment ions. The deconvolution was carried out using a procedure developed in our laboratory, which is based on the maximum entropy routine and will be reported elsewhere (Abzalimov, manuscript in preparation).

Figure 3.

Evolution of isotopic distributions of selected fragment ions following initiation of HDX in solution at pH 7, 60% MeOH: b182+(A); y182+ (B), and y242+ (C).

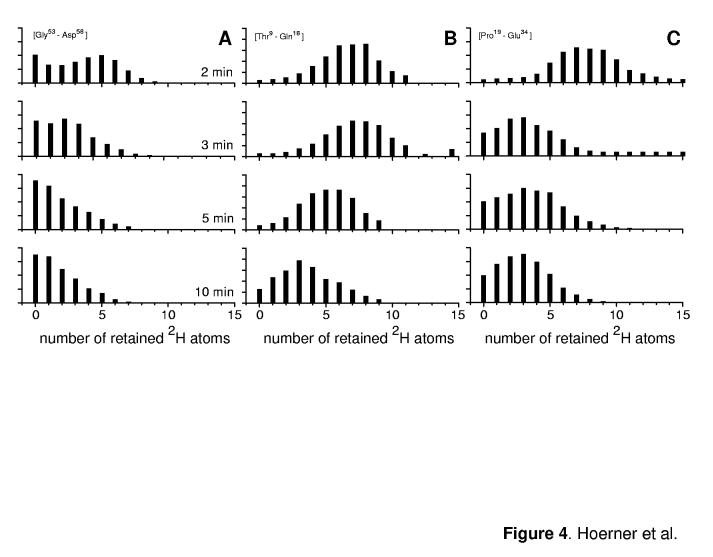

The results of deconvolution are shown in Figure 4, where panel A represents time evolution of the deuterium content of the Gly53→Asp58 segment. The deuterium distribution is clearly bimodal and, in contrast to the global HDX patterns presented in Figure 2C, the exchange within this segment of the protein is correlated. Indeed, a prominent maximum in the distribution corresponding to zero retained 2H atoms can be seen at the earliest time-point (2 min of exchange in solution, upper graph in Figure 4A). This part of the distribution corresponds to a conformer that fails to provide any protection within the Gly53→Asp58 segment. The other part of the distribution has a maximum, whose position indicates full protection of the segment at the time of the initial measurement (six protected amides following 2 min of exchange). Position of this maximum shifts over time, suggesting that the protection is lost due to fast structural fluctuations. This occurs in parallel with the exchange through global opening events, which is responsible for the observed correlated character of the exchange within this segment.

Figure 4.

Deconvolution of deuterium contents of several Ub segments based on experimentally measured isotopic distributions of overlapping fragment ions: [Gly53→Asp58] (A); [Thr9→Glu18] (B), and [Pro19→Glu34] (C).

Not all protein segments exhibit full (or even significant) protection at the time of the initial measurement. Less than half of the amides remain protected in Ser65→Leu71 and Arg72→Gly76 segments following 2 min of exchange (Figure 7). One feature, however, is common to all segments in the C-terminal half of Ub, namely the presence of fully exchanged species. This feature is notably missing in the exchange patterns of protein segments in the N-terminal part of the protein, e.g. Thr9→Gln18 and Pro19→Gln34 (Figure 4 B and C). The distributions are not bimodal, and their maxima gradually shift towards lower 2H content, indicating exchange through fluctuations without any contributions from the global opening events.

Figure 7.

Deconvolution of deuterium contents of several Ub segments based on experimentally measured isotopic distributions of overlapping fragment ions following 2 minutes of exchange in solution: [Gly53→Asp58] (A); [Tyr59→Glu64] (B); [Ser65→Leu71] (C); and [Arg72→Gly76] (D).

DISCUSSION

Ubiquitin is a highly conserved small single domain protein, which mediates proteasomal degradation in eukaryotic cells and is also intimately involved in a variety of other cellular processes (23, 24). One intriguing feature of Ub is its ability to populate a partially folded state (the so-called A-state) under a variety of non-native conditions. While the canonical conditions that are most frequently used to study the A-state of Ub are 60% methanol (by volume) at pH 2, it can also be populated to a certain degree in the presence of alcohol at higher pH (25). Contrary to the classical view of the molten globular state, many studies indicate that the A-state of Ub is in fact a partially unfolded state, where the near-native structure is largely preserved in the N-terminal portion of the protein, while the C-terminal segment becomes highly dynamic (18). Far UV CD measurements indicate that the helical content of Ub is significantly higher under conditions stabilizing the A-state, which had been attributed to high helical propensity of the dynamic non-native C-terminal segment forming a transient helix (18). However, earlier studies concluded that this segment actually maintains a near-native conformation in the A-state (19). More recently, Cordier and Grzesiek were able to characterize the network of hydrogen bonds in the A-state by measuring scalar couplings between 15N nuclei of H-bond donors (amides) and 13C nuclei of H-bond acceptors (carbonyls) of Ub at pH 2 60% methanol (26). These measurements indicated that the H-bond network within the N-terminal part of Ub is largely preserved (although somewhat weakened) in the A-state, while the C-terminal portion undergoes significant re-arrangement, giving rise to a helical connectivity pattern NiH→Oi-4 (26).

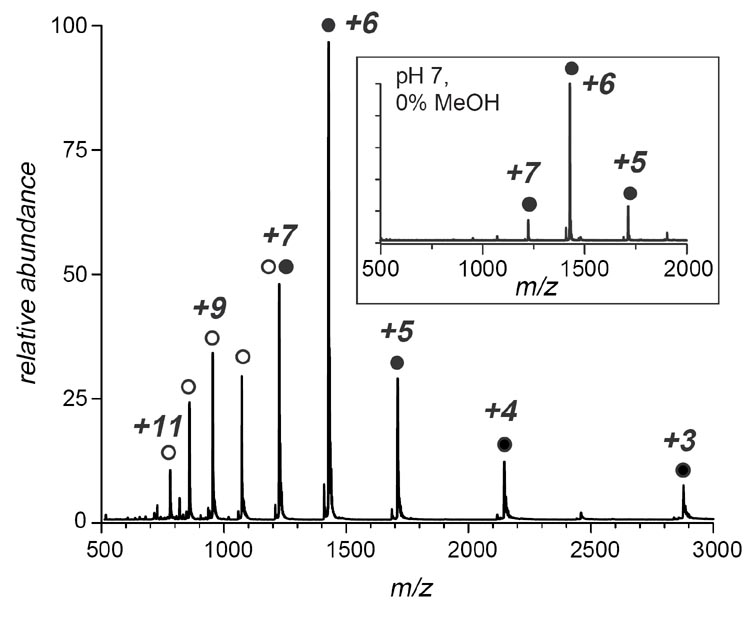

One of the major factors likely contributing to the apparent contradictions regarding the structure of Ub A-state is the difficulty associated with characterization of a specific protein state when other states may be present as well. Indeed, the solution conditions that are commonly used to "stabilize" the A-state of Ub do not result in complete disappearance of the native state of this protein. Analysis of protein ion charge state distributions in ESI mass spectra of Ub acquired at pH 2 60% methanol suggest that two other conformers (native state and random coil) are present in solution alongside the A-state at equilibrium, although the latter is the principal species (20). Since most biophysical methods do not afford clear distinction among various protein states coexisting under equilibrium, any signal arising from the native protein (or indeed random coil) may interfere with characterization of the A-state.

We sought to exploit the unique ability of mass spectrometry to study the equilibrium states in a distinct fashion, so that characterization of the native-like structural features of Ub A-state is unaffected by the signal from the native state of the protein. Distinct detection of different conformers can be afforded in HDX MS measurements only under conditions favoring correlated exchange, when the distinction among the conformers is made based upon the differences in their exposure to solvent. Since correlated exchange patterns can only be observed when the intrinsic exchange rate of unprotected amides exceeds the refolding rate (conditions known as EX1 regime), our measurements had to be carried out at elevated pH (neutral and above) to insure efficient base catalysis of the intrinsic exchange reactions. Previously we have used ESI MS and CD spectroscopy to demonstrate that in the presence of alcohol (over 40% by volume) a significant fraction of Ub molecules populate an intermediate state, which had been identified as the A-state (20). HDX MS profiles of Ub acquired at pH 7 60% methanol are clearly bimodal during the first several minutes of protein exposure to the exchange buffer (Figure 2C). Two Ub species can be easily distinguished from one another, based on the significant difference of their backbone protection (47 amides for the one of the species and 24 for another following 2 min of protein exposure to exchange buffer). Based on the measured protection of the amide backbone, these two Ub species are assigned as the native state (N-state) and the A-state. An intriguing feature of this set of spectra is the absence of the signal corresponding to the fully exchange protein molecules. This is surprising, since analysis of Ub ion charge state distributions in ESI mass spectra suggest that a minor fraction of the protein does populate the random coil state. Therefore, fully correlated exchange was expected to reveal presence of all three conformers, as indicated on the simulated profiles presented in Figure 5A, which were calculated under the assumption that amide exchange within this system follows an ideal EX1 scenario. In other words, it was assumed that a fraction of amides become unprotected and exchange cooperatively upon protein transition to the A-state from the native conformation, while the rest of amides exchange cooperatively upon unfolding of the A-state (see Supplementary Information for a more detailed discussion of HDX simulation presented in Figure 5).

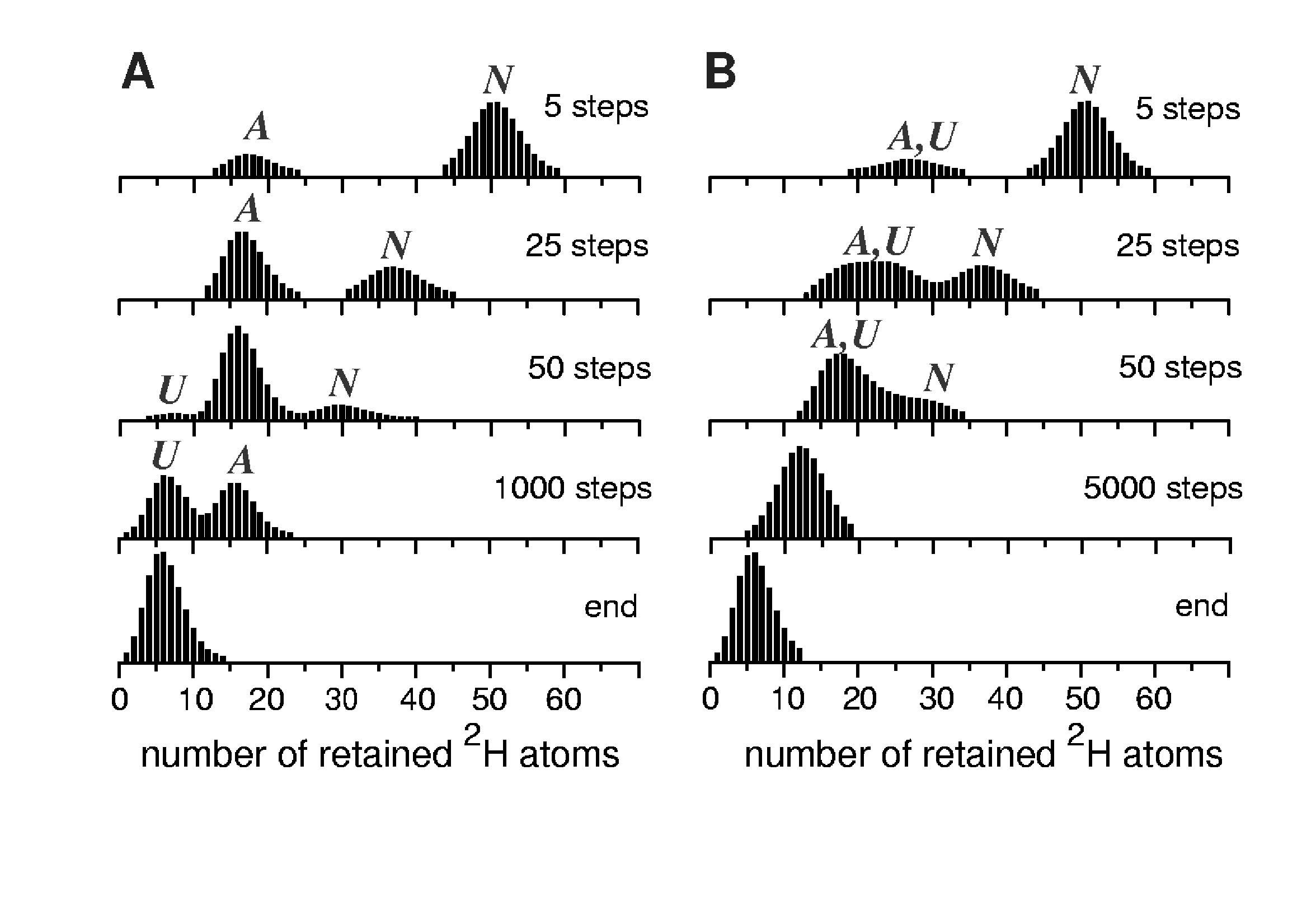

Figure 5.

Simulated exchange for a model three-state system: fully correlated exchange (A) and semi-correlated exchange (B). The single major difference between these two sets is that the residence time of the protein in the U-state was very short in the latter case, thus limiting the extent of amide exchange accompanying unfolding of the A-state (see Supporting Information for more detail).

Further increase of pH (up to pH 9) resulted in overall acceleration of HDX without changing the bimodal character of the observed exchange profiles (data not shown). Tt must be noted that fast intrinsic exchange alone is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for observing fully correlated exchange patterns. Indeed, each opening event must expose a set of amides to solvent simultaneously (cooperative unfolding), or else the observed exchange pattern will be uncorrelated even if labeling of each exposed amide is a very fast process. For example, gradual shift of the isotopic cluster corresponding to the highly protected Ub species towards lower m/z likely corresponds to amide exchange from the native state through local structural fluctuations (27), analogous to behavior observed for two-state proteins (11). At the same time, gradual decline of the intensity of the isotopic cluster corresponding to the N-state and an increase of the abundance of the cluster corresponding to the A-state is indicative of a first-order transition between these two states. Apparently, the reverse activation energy barrier separating A-state from the global free energy minimum (N-state) is high enough, so that each Ub molecule visiting the A-state becomes trapped in it long enough to allow complete (or near-complete) exchange of all amides that become exposed to solvent upon the N → A transition.

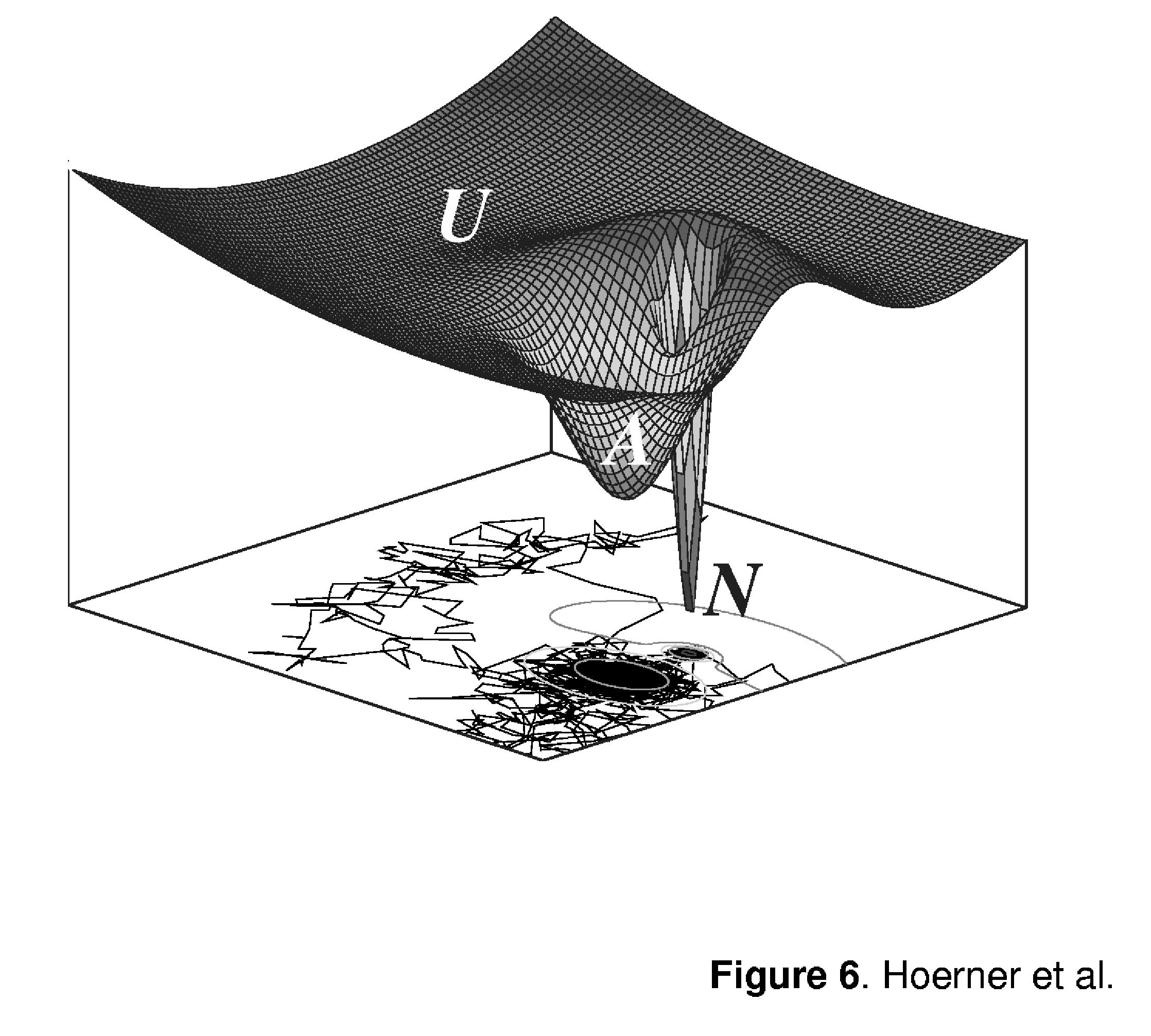

Gradual shift of the isotopic cluster corresponding to the A-state towards lower m/z is indicative of continuous uncooperative exchange of amides that initially remained protected upon the N → A transition. These processes may be viewed as structural fluctuations within the A-state, similar to those occurring in the fully structured N-state of the protein (vide supra). Unlike the local dynamics within the N-state of the protein, structural fluctuations in the A-state seem to affect all amides, as the entire isotopic cluster gradually shifts over time towards the endpoint of the exchange. This actually makes it impossible to distinguish these fluctuations of the A-state from short-lived transitions to the unstructured state of the protein (random coil, or U). Although the random coil is often perceived as a protein state lacking any stable structure and, therefore, protection, a brief sampling of this state by a protein does not necessarily expose all of the backbone amides to solvent simultaneously. Since the random coil is a macrostate representing an enormous ensemble of microstates, many of which exhibit some degree of structure and, therefore, protection (28), brief sampling of the U-state does not necessarily lead to a complete exchange of the entire backbone even if the intrinsic exchange rate is very high. This situation can be illustrated using a minimalist representation of a model energy landscape similar to that depicted in Figure 6, which utilizes a Brownian-dynamic view of protein conformational kinetics (29). A protein molecule is perceived as a particle moving along the protein free energy surface, which is comprised of several basins of attraction corresponding to various states (three in the case of Ub). The narrow potential well on the diagram shown in Figure 6 corresponds to the N-state of the protein, a more diffuse higher energy local minimum corresponds to the A-state, and the third basin of attraction comprises a collection of microstates, which collectively represent the random coil, or U-state.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional representation of a minimalist energy landscape for a three-state protein. Traces at the bottom of the three-dimensional diagram represent projections of a simulated motion of a Brownian particle on this potential surface. Densities of trajectories within various basins of attraction represent Boltzmann weights of the corresponding states, while the number of steps between two successive crossings of the basin boundaries are indicative of the particle residence time within these states.

While the relative occupancies of these states are determined in thermally equilibrated systems by Boltzmann statistics (i.e., free energies of the states), the frequency of traversing the boundaries separating various states will depend upon the ratio of temperature to activation energy. Very low (or indeed non-existent) reverse activation energy barrier separating the U-state from the basin of attraction of the A-state makes any transitions to the former relatively short-lived and allows the protein to sample only a small fraction of microstates within the random coil conformation before it returns to a partially protected A-state. In this view of protein dynamics, the difference between local structural fluctuations within the A-state and short-lived A → U transitions (with zero reverse activation energy barrier) appears to be largely semantic. Indeed, a limited number of backbone amides exposed to solvent each time U-state is sampled can be viewed as a local fluctuation. This, of course, would make the exchange from the U-state uncooperative, despite high intrinsic exchange rate of unprotected amides. Simulations of the exchange reactions in this model (EX1 regime for amides becoming exposed upon N → A transition and EX2 regime for the rest of the amides, i.e. A → U transition) yield HDX patterns, which are qualitatively very similar to those observed experimentally (Figure 5B, see also Supporting Information for a more detailed discussion of HDX simulation).

Our interpretation of the experimentally obtained HDX data and comparison with the simulation of exchange processes in the model system invokes the notion of a short-lived conformational transition from A to U as a process responsible for the completion of the amide exchange. The uncorrelated character of the exchange is caused by the inability of the protein molecule to sample an adequate number of microstates within the macrostate U during a single unfolding event, a view consistent with the notion of a second-order transition. Since only a limited number of amides are affected during each opening event, such transient samplings of the U-state can also be viewed as local structural fluctuations within the A-state.

Local backbone dynamics in the A-state of ubiquitin. The analysis of global dynamics of Ub presented in the previous section suggests that the two distinct isotopic clusters in the bimodal isotopic distribution of Ub ions visible in ESI mass spectra during first several minutes of exchange in solution correspond to the N-state (a narrow cluster at higher m/z) and the A-state of the protein (more diffuse cluster at lower m/z). While evolution of the backbone protection pattern of the A-state is obviously influenced by frequent sampling of the U-state (vide supra), it does not contain any contributions from the N-state of the protein. Therefore, HDX MS measurements provide a unique opportunity to investigate the properties of a dynamic A-state without any interference from the native protein. In addition to this global dynamics information, combining HDX in solution with protein ion fragmentation in the gas phase allows the A-state structure to be probed selectively (i.e., without interference from the N-state).

One intriguing feature of the isotopic distributions of Ub fragment ions is that the bimodal character, which is so prominently displayed by the intact protein ions (Figure 2C), can only be seen for fragment ions derived from the C-terminal part of the protein (y-ions). At the same time, fragment ions derived from the N-terminal half of the protein (b-ions) display single-modal isotopic clusters. Comparison of evolution of isotopic distributions of b182+and y182+fragment ions (Figure 3) clearly shows that amide exchange within these two similarly sized segments proceeds through different mechanisms. The exchange within the C-terminal segment exhibits correlated character, while the N-terminal segment of the same size undergoes only slow uncorrelated exchange.

Deconvolution of isotopic distributions of overlapping fragment ions allows the exchange behavior to be studied at the level of relatively short segments covering the entire protein sequence. In this work our attention was focused on several segments that form distinct elements of secondary structure in the native conformation of Ub. Specifically, we examined behavior of the following segments: [Thr9→Glu18] (based on b18 an b8), [Pro19→Glu34] (based on y58 an y42), and [Gly53→Asp58] (based on y24 an y18). The first two of these three segments represent a β-strand (β2) and a helix (α1) in the native conformation of Ub, which were both previously postulated to be preserved in the A-state (18, 26). The third segment, on the other hand, represents a helix-turn-helix motif in the native conformation, which was postulated to become a part of a transient helix in the A-state of the protein (18, 26). Evolution of the deuterium content for each of these three segments is shown in Figure 4. Only the [Gly53→Asp58] segment has a bimodal deuterium distribution during first several minutes of exchange. The two maxima in the initial distribution (upper trace in Figure 4A) correspond to a fully exchanged segment (zero retention) and fully protected (five out of six amides) segment. This second cluster rapidly diminishes in abundance and also shifts to lower deuterium content, suggesting that the corresponding protein species exchanges through both global opening events (which leaves no protected amides) and local structural fluctuations (which expose only a fraction of the segment's amides to solvent at a time). The single maximum of the initial isotopic distribution of the [Thr9→Glu18] segment of Ub (upper trace in Figure 4B) also corresponds to a high degree of protection (seven amides out of ten). This protection is gradually lost through uncorrelated exchange, suggesting that in both A- and N-states of Ub amide exchange within this segment proceeds only through local structural fluctuations and is not aided by any cooperative unfolding events. The adjacent segment, [Pro19→Glu34], is only partially protected at the time of the initial measurement (eight amides out of fifteen, upper trace in Figure 4C), but it also loses its protection only through uncorrelated exchange without any evidence for cooperative unfolding of this segment in either A- or N-state of the protein.

The absence of a bimodal character among the isotopic distributions of the segments of Ub located in the N-terminal half of the protein is very telling, as it clearly indicates that their behavior is identical in both N- and A-states of the protein. This is in sharp contrast with the [Gly53→Asp58] segment derived from the C-terminal half of the protein, for which a very clear distinction can be made between the two states of the protein. Furthermore, other segments in the C-terminal region also display bimodal isotopic distributions (Figure 7), allowing a distinction between the two states to be made. Importantly, some of these segments (e.g., [Tyr59→Glu64]) have considerable number of amides protected in the N-state, while none of the segments appears to have any protection in the A-state of the protein, at least on the time scale of our measurements.

Absence of any detectable protection in the C-terminal part of the protein that could be ascribed solely to formation of the non-native structure specific to the A-state (transient helix) is in line with recent observations by Forest, Smith and co-workers, who noted that "this paradox, the presence of significant residual secondary and tertiary structures detected by optical probes and the total deuteration of its amide protons detected by H-D exchange and mass spectrometry, could be explained by a highly dynamic [character of] molten globule" (17). At the same time, we note that the N-terminal half of Ub is quite stable in the A-state of the protein, as its dynamic characteristics appear to be indistinguishable from those of the same element in the native conformation of the protein. In fact, the A-state of Ub does not fit a classical definition of a molten globular state, and would probably be better described as a partially folded state of the protein. What makes it very unusual is the fact that part of the protein, which is not natively folded, also assumes certain (non-native) structure, even though it is highly dynamic and eludes straightforward characterization by HDX MS. Furthermore, Ub is a very small protein, and the presence within a single domain of two distinct parts that display such dramatic difference upon mild denaturation is indeed rather intriguing.

Until recently, there was a consensus view that renaturation of Ub is a simple two-state process, which does not involve any kinetic intermediates. This view is beginning to change now following a report by Konermann and co-workers, who detected a kinetic intermediate state during Ub refolding (30). Even earlier peptide dissection studies hinted that Ub folding may proceed through formation of a transient species in which N-terminal part acquires near-native structure (31). It remains to be seen if the kinetic folding intermediate detected by Konermann and co-workers is identical or similar to the A-state of Ub, a task that can be accomplished by combining Konermann's pulsed HDX MS technique (9, 32) and protein ion fragmentation in the gas phase. Finally, Ernst and co-workers noted that at least some biological functions of Ub involve large-scale intramolecular motions and, therefore, must require a much higher degree of protein flexibility than is available in the native conformation (18). It is possible that such flexibility is attained via transient sampling of the A-state. Indeed, all but one of the key hydrophobic residues (Leu8, Leu43, Ile44 Leu50, Leu69, Val70, and Leu71) of Ub, which are known collectively as the hydrophobic patch and are critical for proteasomal degradation, endocytosis and virus budding (33-35), are confined to the protein segment that becomes highly dynamic in the A-state. The Lys48 residue, whose side chain is used to form polyubiquitin chains which target proteins for proteasomal degradation, is also located within this segment of the protein. Therefore, increased dynamics within this region may be an important facilitator of Ub binding to a variety of its partners in numerous interaction networks that involve this protein (36).

CONCLUSIONS

Molten globule, as well as other non-native states, possesses inherent plasticity and cannot be isolated physically for direct characterization by most biophysical techniques without interference from other equilibrium states. HDX MS measurements carried out in a semi-correlated exchange regime are unique in that they allow for both native and partially unfolded states of Ub to be observed and characterized both globally and locally. The results of the present work indicate that the A-state of Ub does not fit a classical definition of a molten globular state, but rather has characteristics of a partially unfolded state. While the results of HDX MS measurements of Ub global backbone dynamics do suggest that unfolding of the A-state is a slow second-order transition, the non-natively folded segment of the A-state (a transient helix) does not have any detectable amide protection. At the same time, the dynamic behavior of the N-terminal segment of the protein is identical to that of the natively folded conformer under the same conditions. The surprisingly uneven distribution of the backbone flexibility in the non-native state of Ub may be an important structural feature, which was evolutionary optimized to facilitate its interactions with a variety of its partners in a plethora of cellular processes in which this protein is utilized.

Supporting Information 1.

ESI MS of ubiquitin at pH 7, 60% MeOH acquired with a JMS-700 MStation (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) two-sector mass spectrometer. Bimodal charge state distribution indicates that a significant fraction of protein molecules assumes non-native conformation in solution (represented by protein ion peaks +7 through +11). A reference mass spectrum of ubiquitin acquired under near-native conditions (no alcohol used as a co-solvent) is shown in the boxed inset. A detailed description of protein ion charge state distribution analysis can be found in Mohimen, et al., Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 4139

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.K.H. was supported in part through a UMass-sponsored Chemistry-Biology Interface Program fellowship. The authors wish to thank Dr. Rinat R. Abzalimov for his help in deconvoluting the deuterium distributions of Ub segments and Dr. Stephen J. Eyles for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R01 GM61666

N is the total number of amides in the model protein and L is the number exchangeable through local structural fluctuations in the native state

time increment τ (a simulation step) is defined as , where both kcl and kop refer to the N → U transition (assumed to be the slowest transition in the system)

ABBREVIATIONS: HDX, hydrogen/deuterium exchange; MS, mass spectrometry; ESI, electrospray ionization; CAD, collision-activated dissociation; NOE, Nuclear Overhouser Enhancement; Ub, ubiquitin

Supporting Information

Simulation of HDX MS patterns for a three-state protein was carried out using an algorithm developed as an extension of our model of a two-state system, which was described in detail elsewhere (11). The extension of the two-state model was accomplished by introducing an intermediate state (which accounts for the A-state of Ub in this work), to which a limited exchange competence was assigned. The limited exchange competence means that only K (L < K < N) amides can be exchanged from this state.1 The exchange kinetics from the intermediate state is determined by both PA(probability that a protein molecule samples this A-state during time interval τ)2 and PAex, probability of exchange of any single amide (from the pool of K identical ones) during lifetime of the protein in the A-state:

| (1) |

where kclA is a rate constant for the A → N transition. This situation corresponds to a potential energy diagram depicted in Figure 6. In this case a peak I(M,tx), corresponding to a protein species retaining M (M ≤ N) 2H atoms at time tx, will be transformed at time to a distribution that can be calculated using a rather straightforward expansion of equations (21-22) from our earlier work (11):

if M>N-L;

if N-K < M ≤ N-L; and

if M ≤ N-K.

A more realistic generalization of this rather simplistic three-state model needs to account for structural fluctuations of the A-state. This can be done in a fashion similar to that used for treatment of structural fluctuations in the native state (11) with one important exception. The full range of fluctuations within the native state (L) was assumed to be rather limited due to the presence of stable tertiary structure, since there is abundant evidence that such fluctuations primarily affect amides that are positioned close to the protein surface (27). If the A-state lacks a stable hydrophobic core (26), the range of structural fluctuations within the A-state should be unlimited (i.e., any one of the N-K protected amides can be exchanged from the A-state through fluctuations). This, of course, would make the activated A-state indistinguishable from the fully unstructured U-state (as shown in Figure 6). Exchange kinetics within the A-state occurring via structural fluctuations will depend on PA→U (probability of sampling U from A during lifetime of the latter), PUex (probability of exchange for any single amide out the pool of N-K identical ones during such fluctuation event):

| (5) |

There are two refolding rate constants in the denominator of (5), since there are two channels of the U-state deactivation (return to either A or N). The former would almost always be preferred under mildly denaturing conditions, since the corresponding reverse activation energy barrier ΔG‡U→A is zero or very close to zero. The two de-activation channels will compete under near-native conditions, when ΔG‡U→N is also expected to be insignificant. Equations (2-4) can now be easily generalized to account for structural fluctuations within the A-state:

if M>N-L;

if N-K < M ≤ N-L; and

if M ≤ N-K.

Equations (6-8) were used to calculate the exchange profiles shown in Figure 5. HDX simulation represented by the profiles shown in Figure 5A (correlated exchange) was carried out using the following set of parameters: probability of sampling U-state from N-state during time interval τ, PN→U= 0.0001; probability of sampling A-state from N-state during the same time interval, PN→A= 0.005; probability of sampling U-state from A-state during the lifetime of the latter, PA→U= 0.02; probability for a any single amide from a set of L identical ones to be exchanged during the time interval τ (exchange through local fluctuations within the N-state), PNex = 0.005; probability for any single amide from a set of K identical ones to be exchanged during the lifetime of A-state (exchange through local fluctuations within the A-state), PAex = 0.95; and probability for any single amide from a set of K identical ones to be exchanged during the lifetime of U-state (exchange through unfolding of the A-state), PUex = 0.90. Simulation of semi-correlated exchange (Figure 5B) was carried out using the following set of parameters: probability of sampling U-state from N-state during time interval τ, PN→U= 0.0001; probability of sampling A-state from N-state during the same time interval, PN→A= 0.005; probability of sampling U-state from A-state during the lifetime of the latter, PA→U= 0.02; probability for any single amide from a set of L identical ones to be exchanged during the time interval τ (exchange through local fluctuations within the N-state), PNex = 0.005; probability for any single amide from a set of K identical ones to be exchanged during the lifetime of U-state (exchange through local fluctuations within the A-state), PAex = 0.02; and probability for any single amide from a set of K identical ones to be exchanged during the lifetime of U-state (exchange through unfolding of the A-state), PUex = 0.10. In both cases, the number of amides amenable to exchange through local structural fluctuations within the N-state was assumed to be L = 20; the number of amides protected within the A-state was assumed to be K = 30; and the total number of exchangeable amides was assumed to be N = 50. The single major difference between these two sets of conditions is that the residence time of the protein in the U-state was very short in the latter case, thus limiting the extent of amide exchange accompanying unfolding of the A-state.

All calculations were carried out using FORTRAN90. Complete listings of the programs are available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ptitsyn OB. How the molten globule became. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:376–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ptitsyn OB. Molten globule and protein folding. Adv. Protein Chem. 1995;47:83–229. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arai M, Kuwajima K. Role of the molten globule state in protein folding. Adv. Protein Chem. 2000;53:209–82. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(00)53005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z. Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/bi012159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Privalov PL. Intermediate states in protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;258:707–25. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redfield C. Using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study molten globule states of proteins. Methods. 2004;34:121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltashov IA, Eyles SJ. Mass spectrometry in molecular biophysics : conformation and dynamics of biomolecules. John Wiley; Hoboken, N.J: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaltashov IA, Eyles SJ. Studies of biomolecular conformations and conformational dynamics by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2002;21:37–71. doi: 10.1002/mas.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konermann L, Simmons DA. Protein-folding kinetics and mechanisms studied by pulse-labeling and mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2003;22:1–26. doi: 10.1002/mas.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaltashov IA. Probing protein dynamics and function under native and mildly denaturing conditions with hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2005;240:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao H, Hoerner JK, Eyles SJ, Dobo A, Voigtman E, Mel′cuk AI, Kaltashov IA. Mapping protein energy landscapes with amide hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry: I. A generalized model for a two-state protein and comparison with experiment. Protein Sci. 2005;14:543–557. doi: 10.1110/ps.041001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaltashov IA, Eyles SJ. Crossing the phase boundary to study protein dynamics and function: combination of amide hydrogen exchange in solution and ion fragmentation in the gas phase. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002;37:557–565. doi: 10.1002/jms.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maier CS, Kim O-H, Deinzer ML. Conformational properties of the A-state of cytochrome c studied by hydrogen/deuterium exchange and electrospray mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 1997;252:127–135. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Last AM, Schulman BA, Robinson CV, Redfield C. Probing subtle differences in the hydrogen exchange behavior of variants of the human α-lactalbumin molten globule using mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:909–19. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempsey CE. Hydrogen exchange in peptides and proteins using NMR-spectroscopy. Progr. Nucl. Magn. Res. Spectrosc. 2001;39:135–170. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna MMG, Hoang L, Lin Y, Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazon H, Marcillat O, Forest E, Smith DL, Vial C. Conformational dynamics of the GdmHCl-induced molten globule state of creatine kinase monitored by hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5045–54. doi: 10.1021/bi049965b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brutscher B, Bruschweiler R, Ernst RR. Backbone dynamics and structural characterization of the partially folded A state of ubiquitin by 1H, 13C, and 15N nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13043–13053. doi: 10.1021/bi971538t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan Y, Briggs MS. Hydrogen exchange in native and alcohol forms of ubiquitin. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11405–11412. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohimen A, Dobo A, Hoerner JK, Kaltashov IA. A chemometric approach to detection and characterization of multiple protein conformers in solution using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:4139–4147. doi: 10.1021/ac034095+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engen JR, Smith DL. Investigating protein structure and dynamics by hydrogen exchange MS. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:256A–265A. doi: 10.1021/ac012452f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoerner JK, Xiao H, Dobo A, Kaltashov IA. Is there hydrogen scrambling in the gas phase? Energetic and structural determinants of proton mobility within protein ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7709–7717. doi: 10.1021/ja049513m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roos-Mattjus P, Sistonen L. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Ann. Med. 2004;36:285–295. doi: 10.1080/07853890310016324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jourdan M, Searle MS. Insights into the stability of native and partially folded states of ubiquitin: effects of cosolvents and denaturants on the thermodynamics of protein folding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10317–25. doi: 10.1021/bi010767j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordier F, Grzesiek S. Quantitative comparison of the hydrogen bond network of A-state and native ubiquitin by hydrogen bond scalar couplings. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11295–301. doi: 10.1021/bi049314f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maity H, Lim WK, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Protein hydrogen exchange mechanism: local fluctuations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:153–160. doi: 10.1110/ps.0225803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith LJ, Fiebig KM, Schwalbe H, Dobson CM. The concept of a random coil. Residual structure in peptides and denatured proteins. Fold. Des. 1996;1:R95–R106. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(96)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian H. From discrete protein kinetics to continuous Brownian dynamics: A new perspective. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1–5. doi: 10.1110/ps.18902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan J, Wilson DJ, Konermann L. Pulsed hydrogen exchange and electrospray charge-state distribution as complementary probes of protein structure in kinetic experiments: implications for ubiquitin folding. Biochemistry. 2005;44 doi: 10.1021/bi050575e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolton D, Evans PA, Stott K, Broadhurst RW. Structure and properties of a dimeric N-terminal fragment of human ubiquitin. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:773–787. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmons DA, Dunn SD, Konermann L. Conformational dynamics of partially denatured myoglobin studied by time-resolved electrospray mass spectrometry with online hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5896–5905. doi: 10.1021/bi034285e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sloper-Mould KE, Jemc JC, Pickart CM, Hicke L. Distinct functional surface regions on ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30483–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang RS, Daniels CM, Francis SA, Shih SC, Salerno WJ, Hicke L, Radhakrishnan I. Solution structure of a CUE-ubiquitin complex reveals a conserved mode of ubiquitin binding. Cell. 2003;113:621–630. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher RD, Wang B, Alam SL, Higginson DS, Robinson H, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Structure and ubiquitin binding of the ubiquitin-interacting motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:28976–28984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoemaker BA, Portman JJ, Wolynes PG. Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: the fly-casting mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:8868–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160259697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]