Abstract

We have investigated the apical membrane permeability for CO2 of intact epithelia of proximal and distal colon of the guinea pig. The method used was the mass spectrometric 18O-exchange technique previously described. In a first step, we determined the intraepithelial carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity by studying vital isolated colonocytes before and after lysis with Triton X-100. Intraepithelial CA activity was found to be 41 000 and 900 for proximal and distal colon, respectively. Then 18O-exchange measurements were done with stripped intact epithelial layers, which on their apical side were exposed to the reaction solution containing 18O-labelled CO2 and HCO3−. The mass spectrometric signals in these measurements are determined by the intracellular epithelial CA activity, and by the apical membrane permeabilities for CO2 and HCO3−, PCO2 and PHCO3. From the signals, we calculated the two permeabilities while inserting the CA activities obtained from isolated colonocytes. From layers of intact colon epithelium, the apical PCO2 was determined to be 1.5 × 10−3 cm s−1 for proximal and 0.77 × 10−3 cm s−1 for distal colon. These values are ≥200 times lower than the PCO2 of the human red cell membrane as studied with the same technique (0.3 cm s−1). We conclude that the apical membrane offers a significant resistance towards CO2 diffusion, which implies that a major drop in CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) will occur across the apical membrane when luminal pCO2 is higher than basolateral or capillary pCO2. In view of the very high pCO2 that can occur in the colonic lumen, this property of the apical membrane constitutes a significant protection of the cell against the high acid load associated with high pCO2.

It has been reported that the epithelial cells of isolated gastric glands fail to exhibit the changes in intracellular pH after step increases in luminal partial pressure of ammonia or CO2 (pNH3 or pCO2), as they are to be expected when the apical membrane is permeable to these gases (Boron et al. 1994; Waisbren et al. 1994). Similarly, it has been observed that intracellular pH of the epithelial cells of isolated colonic crypts does not increase when pNH3 in the lumen is raised, but does so immediately when pNH3 is raised on the basolateral side (Singh et al. 1995). In both cases, the authors concluded that there must be a permeability barrier to gases in the apical membrane of these epithelia. Bacteria can generate high concentrations of ammonia/ammonium in the colon from nitrogen-containing substances (Lin & Visek, 1991), and bacterial metabolism can produce pCO2 of up to 0.5 atm (50.66 kPa) in the lumen of the colon of several species (Rasmussen et al. 1999, 2002). High pNH3 can have toxic effects and an extreme pCO2 can constitute a severe acid load for epithelial cells if these gases can freely permeate into the intracellular spaces. Thus it appears to be physiologically useful if the apical membrane constitutes a gas barrier that protects the cells from these gases. Other apical membranes in the kidney and in the urinary bladder have also been reported to present diffusion resistances towards ammonia (Kikeri et al. 1989; Negrete et al. 1996; Rivers et al. 1998). We wanted to investigate the behaviour of the apical membranes of proximal and distal colon towards the diffusion of CO2 using a mass spectrometric technique to measure CO2 permeability of biological membranes.

We have observed by a mass spectrometer the exchange of 18O between CO2, HCO3− and H2O occurring in a bathing solution that is in contact with the intracellular epithelial compartment via the apical membrane. This technique has previously been applied to guinea-pig colon, a piece of which was slid over a solid cylinder after having been inverted to expose the apical side of the mucosa to the surrounding bath, and in this configuration it allowed us to measure the intracellular carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity and the bicarbonate permeability of the apical membrane of colonic epithelium (Böllert et al. 1997a, b). In the theory used to evaluate the data of these previous studies, an important parameter that was assumed to be not rate-limiting was the CO2 permeability of the membrane. We have now developed an extension of the theory of the process of 18O exchange in the presence of cells that treats the CO2 permeability of the membrane as a parameter that can also be a limiting step in the overall process (Wunder et al. 1997; Wunder & Gros, 1998; Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). We have applied this theory to a series of mass spectrometric measurements of 18O exchange across the apical membrane of colonic mucosa from the guinea pig, and this allows us to report here values of the CO2 and HCO3− permeability of this membrane. The contribution of the intracellular epithelial compartment to 18O exchange depends essentially on three parameters, namely intracellular CA activity and membrane CO2 and HCO3− permeability. Therefore, in order to restrict the number of parameters derived from one type of experiment, we have determined, in a first step, intracellular epithelial CA activity in isolated colonocytes, and then used this figure to obtain the two parameters CO2 and HCO3− permeability from measurements of intact mucosa with the apical side exposed to the bath. This is justified as it has been shown that all intracellular CA present in guinea pig colon is localized within epithelial cells (Lönnerholm, 1977; Lönnerholm et al. 1988). While we obtain a HCO3− permeability of the apical membrane that is similar to the value reported previously (Böllert et al. 1997a, b), we find a CO2 permeability for this membrane that is >100 times lower than the CO2 permeability we have measured with the same technique in human red cells (Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations).

Methods

Solutions and chemicals

Standard reaction solution contained (mm): 103.6 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 0.8 HCl, 2.4 NaH2PO4, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 10 sodium butyrate. Osmolarity of the solution was adjusted to 300 mosmol l−1 using mannitol. pH was adjusted to 7.4.

Rinsing buffer contained (mm): 144 NaCl, 0.5 d, l-dithiotreitol (DTT), 40 mg l−1phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 sodium butyrate.

Buffer solution A, similar to that described by Stieger et al. (1986), contained (mm): 30 NaCl, 5 Na3EDTA, 8 Hepes, 8 Tris, 0.5 DTT, 40 mg ml−1 PMSF, 10 sodium butyrate.

PMSF and DTT were purchased from Sigma; 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-2,2′-stilbenedisulphonate (DIDS) was from Molecular Probes (USA). The extracellular CA sulphonamide inhibitor 1-[5-sulphamoyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl-(aminosulphonyl-4-phenyl)]-2,4,6-trimethyl-pyridinium perchlorate (STAPTPP) was a kind gift from Dr Claudiu T. Supuran (Firenze). 18O-labelled bicarbonate, NaHC18O16O2, was prepared as described by Itada & Forster (1977) from H218O (Euriso-Top, Gif-Sur-Yvette, France). Trypan Blue stain was from Merck. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from Merck.

Mass spectrometric determination of intracellular CA activity and the permeabilities of CO2 and HCO3−

Principle

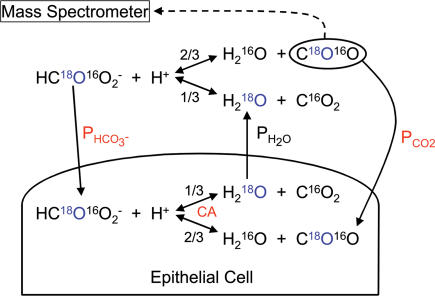

In principle, we used the technique described by Itada & Forster (1977) to study the exchange of 18O-labelled CO2 and HCO3− between an extracellular solution and the intracellular space of cells containing CA activity (Fig. 1). Itada & Forster (1977) showed with red cells that by observing the time course of the species C18O16O (mass/charge, m/z, 46) peak height in a cell suspension with a mass spectrometer, it is possible to determine the intracellular CA activity (Ain) and the bicarbonate permeability (PHCO3) of the cell membranes. The new feature of the present approach is the theoretical treatment of the process of 18O exchange, which does not assume, as Itada and Forster did, that CO2 is infinitely permeable across the membrane. As already reported, in normal human red cells the permeation of CO2 across the cell membrane has a detectable effect on the kinetics of 18O exchange, and thus it is possible to determine the membrane CO2 permeability from measurements of these kinetics (Wunder et al. 1997; Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). Figure 3 shows a set of equations that we use to estimate CO2 permeability (PCO2) from the kinetics of the extracellular concentration of C18O16O. The time course of C18O16O in the extracellular fluid, which is either in contact with the apical side of intact mucosa or contains isolated colonocytes in suspension, is followed by a mass spectrometer using the special inlet system developed by Itada & Forster (1977).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of reactions and transport processes associated with 18O exchange of colon epithelial cells, either in the intact epithelial sheet or as isolated colonocytes in suspension.

The partial pressure of C18O16O in the fluid sample is followed continuously by mass spectrometry. The fractions 2/3 and 1/3 indicate that in each dehydration reaction step there is a 2/3 chance that the 18O of HC18O16O2− ends up in CO2, and a 1/3 chance that it is transferred into water. Because the water pool is very much greater than the pool of CO2/HCO3−, eventually almost all of the 18O will disappear into the water pool. The crucial parameters describing the overall process in the presence of cells are: (1) the intracellular activity of carbonic anhydrase (CA), which is determined in an independent experiment from colonocytes in suspension; (2) the membrane CO2 permeability (PCO2) and; (3) the membrane HCO3− permeability (PHCO3); the latter two are determined from the recorded time course of C18O16O from experiments such as in Figs 4B and 5. The water permeability PH2O of red cells is so high that it does not become rate limiting in these measurements.

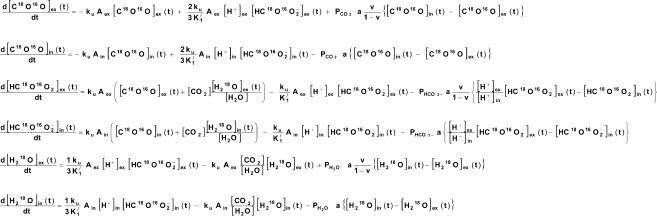

Figure 3. System of six equations describing the processes of Fig. 1 in terms of intra- and extracellular concentration changes over time of labelled CO2, HCO3− and water.

These differential equations are solved by numerically solving the Eigenvalues using the MatLab program package (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). A least-squares method was used to fit ‘theoretical’ curves to the experimental curves of the time course of C18O16O by determining the best values of PCO2 and PHCO3. Aex is extracellular CA activity; Ain, intracellular activity of CA, which is determined from experiments with isolated colonocytes in absence and presence of Triton X-100; ku, velocity constant of the (uncatalysed) CO2 hydration reaction; K1′, first apparent dissociation constant of carbonic acid; v, volume fraction of cells, a surface-to-volume ratio of cells. PH2O, the water permeability of the membrane, is taken to be not rate-limiting.

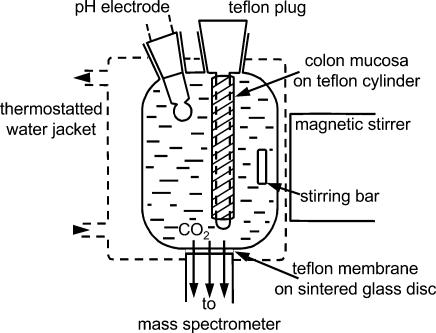

Measuring chamber and inlet system

The measuring chamber is similar to the one described by Wunder et al. (1997). As shown in Fig. 2, it is equipped with a pH electrode, and temperatures can be maintained as desired (20°C). Total reaction volume is 1.7 ml, and it is continuously stirred by a stirring bar driven by an external magnetic stirring device. Mounted into the bottom of the chamber is the inlet system consisting of a 25-µm-thick Teflon membrane that covers and is mechanically supported by a sintered glass disk. The space under the disk is connected directly to the high vacuum of the mass spectrometer by metal tubing. Because the Teflon has a high permeability for gases, there is a continuous diffusion of C18O16O, C16O2 and other gases towards the ion source of the mass spectrometer, giving a continuous signal that is proportional to the respective partial pressure prevailing in the fluid of the measuring chamber. Although the diffusion rates are large enough to give excellent signals in the mass spectrometer, they are small enough to avoid noticeable loss of the gas in the reaction chamber. This can be seen in the signal of C16O2, which remains constant throughout the experiment (30 min). The mass spectrometer (Stable Isotope Detector; Europa Scientific Ltd, Crewe, UK) was set to record continuously and simultaneously the masses m/z 44 (C16O2) and 46 (C18O16O). The response time of the mass spectrometer output after a sudden change in CO2 concentration in the reaction chamber was 3 s.

Figure 2. Inlet system to mass spectrometer.

Slow diffusion of gases dissolved in the reaction solution occurs across a 25-µm-thick Teflon membrane sitting on a sintered glass disk into the high vacuum of the mass spectrometer, and allows continuous recording of the partial pressures of C16O2 (mass 44) and C18O16O (mass 46). The colon epithelium has been stripped from the submucosa and is slid tightly over the Teflon cylinder. In the experiments reported here the mucosal layer is inverted such that the apical membranes face the reaction solution containing C16O2 and C18O16O. The exchanges of the labelled species are then observed across the apical membranes.

To perform experiments, NaHCO3 labelled with 18O was dissolved in the standard reaction solution from which NaHCO3 had been omitted. Temperature was 20°C. The solution was immediately filled into the reaction chamber, and 2 m HCl was added via a pluggable access to the chamber until a pH of 7.40 was established in the solution. The slow (uncatalysed) decay of the C18O16O signal, which was observed therafter, corresponded to the first phase of recordings, such as that of Fig. 4. In one type of experiment, after ∼2 min, a suitable volume of isolated colonocytes was added into the reaction chamber to give a known cytocrit, upon which the biphasic accelerated further decay of C18O16O was seen, which is characteristic of CA-containing cells (Fig. 4). In another type of experiment, a piece of stripped colon with known surface area was slid onto a Teflon cylinder of suitable diameter and length, and introduced into the reaction chamber as illustrated in Fig. 2. This was also followed by a biphasic further decay of C18O16O (Fig. 5). The two phases seen after the initial slow uncatalysed decay were used to calculate PCO2 as explained in the following.

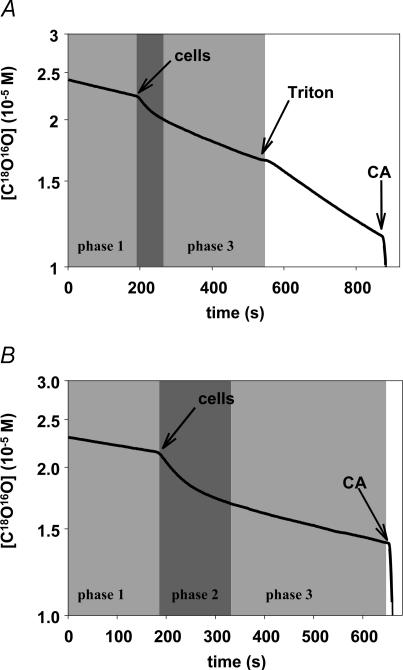

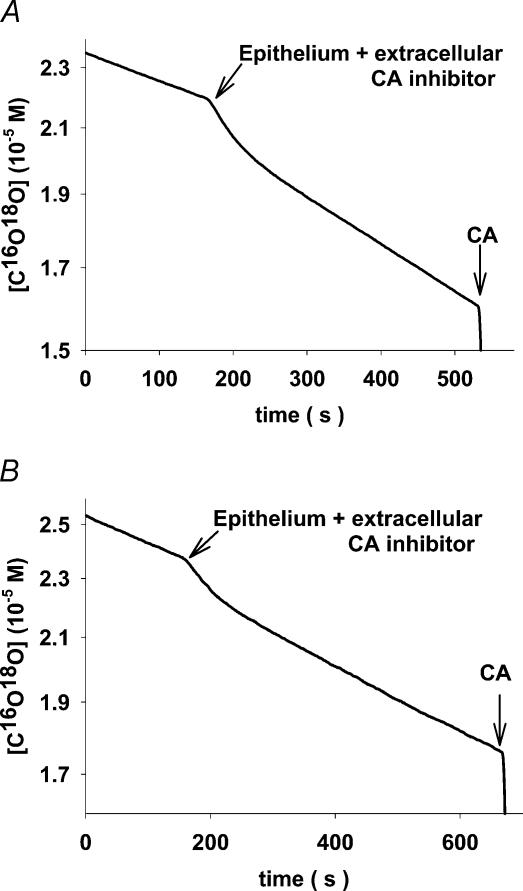

Figure 4. Original mass spectrometric recordings of the decay of C18O16O concentration in suspensions of isolated proximal colonocytes.

The first phase (phase 1) reflects the spontaneous decay of labelled CO2 in the absence of cells and of CA. After the additions of colonocytes, the second phase (phase 2, middle shaded area) exhibits a rapid fall in C18O16O, which is due to fast entry of C18O16O into the cells where it is rapidly converted into HC18O16O2− (this process requiring high membrane PCO2 and high intracellular CA activity). The subsequent slower phase (phase 3), among other processes, represents influx of HC18O16O2− into the cells and is governed by the membrane permeability for HCO3−. A, cells added at the arrow are isolated proximal colonocytes, no extracellular CA inhibitor is present. After addition of Triton X-100, all CA, extra- as well as intracellular, is directly accessible from the reaction solution and behaves therefore as CA in solution, giving a linear slope in the semi-logarithmic plot. The slope of this line over the slope of the initial phase in the figure represents total CA activity of the cells. B, proximal colonocytes were added at the arrow after having been pre-incubated in 10−5m STAPTPP, which continued to be present during the mass spectrometric experiment. Because Aex is inhibited here, the exchange process is determined by Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3. At the end of both experiments, soluble CA is added in excess to rapidly establish isotopic equilibrium.

Figure 5. Original mass spectrometric recordings of intact stripped colonic epithelium exposing the apical side to the reaction solution.

The inverted mucosal layer is slid over the Teflon cylinder as shown in Fig. 2. All experiments are in the presence of the extracellular CA inhibitor STAPTPP. A, proximal colon; B, distal colon. From these types of curve, the apical values of PCO2 and PHCO3 were calculated.

Calculation of CA activities, and CO2 and HCO3− permeabilities, from time courses of C18O16O

As shown in Fig. 1, labelled HCO3−, after having been dissolved, reacts to give either labelled CO2 and unlabelled water (probability 2/3) or unlabelled CO2 and labelled water (probability 1/3). This process implies a depletion of 18O from the CO2/HCO3− pool with almost all of the 18O finally ending up in the water pool, because the latter is about 2000 times greater than the former. The depletion is very slow as long as the CO2 hydration reaction is uncatalysed, as is seen from the initial phase (phase 1) in the recording of Fig. 4. When cells are introduced into this solution, labelled CO2 diffuses rapidly into the cells until intracellular CO2 and HCO3− are labelled to the same extent as the extracellular CO2. This process is rapid when both PCO2 and intracellular activity of CA are high. It causes a substantial decay of the extracellular C18O16O because not only intracellular CO2, but also the 20 times higher intracellular HCO3−, have to be labelled with 18O by means of the extracellular C18O16O that diffuses into the cells. This process is represented mainly by the first rapid phase of the accelerated C18O16O decay observed after the addition of cells (phase 2 of the recordings of Fig. 4). At this point, the extracellular concentration of labelled HCO3− is much greater than its intracellular concentration, and there is disequilibrium between the extracellular labelled species CO2 and HCO3−. Therefore, predominantly during the second slower phase of C18O16O decay after addition of the cells (phase 3 in Fig. 4), labelled HCO3− moves from the extracellular solution into the cells. For these reasons, mainly the first fast phase observed after addition of cells (phase 2 in Fig. 4) allows one to calculate Ain and PCO2, and mainly the second slower phase (phase 3 in Fig. 4) allows one to calculate PHCO3. It is apparent from Fig. 1 that the hydration–dehydration reaction occurs essentially inside the cells because only there is CA activity present. Therefore, the transfer of the label 18O from CO2 to water occurs almost exclusively inside cells. The labelled water then equilibrates between the intra- and the extracellular space.

This process is mathematically formulated by the equations given in Fig. 3. The first two equations describe the change in the concentration of labelled CO2 with time in the extra- and in the intracellular space. They contain the contribution of the hydration and the dehydration reaction to this quantity, and the rate of diffusion of labelled CO2 between extra- and intracellular spaces. The third and fourth equations describe the rate of change of the concentrations of labelled HCO3− in the extra- and intracellular spaces. Again, the contribution of the hydration and the dehydration reaction is considered, and it is taken into account that labelled HCO3− can be generated from labelled CO2 and unlabelled water, or from unlabelled CO2 and labelled water. The last term of these equations describes the transfer of labelled HCO3− across the cell membrane; because in the case of HCO3−, due to its pH-dependent distribution, diffusion does not lead to equal intra- and extracellular concentrations, a correction is applied to the actual extracellular HCO3− concentration as employed by Itada & Forster (1977). The fifth and sixth equations describe the rate of change of the concentration of labelled water, taking into account that dehydration of labelled HCO3− produces labelled water with a probability of 1/3, and hydration of unlabelled CO2 consumes a labelled water with a probability of [H218O]/[H216O]. The constants a (surface to volume ratio of epithelial cells), ku (velocity constant of CO2 hydration), K1′ (first apparent dissocation constant of carbonic acid) and water permeability of the membrane (PH2O; which can be shown to be two orders of magnitude higher than would be critical for the overall rate of the 18O exchange process) were taken from the literature; v (volume of intracellular water per unit volume of suspension) was determined from cytocrit and intracellular water fraction; the extracellular CA activity was usually represented by an acceleration factor (Aex) of 1 (implying zero activity) when no extracellular CA was present. The term av/(1 –v) that appears in the diffusion term of three of the six equations is an approximation of the ratio cellular surface area per extracellular volume. It may be noted that the permeabilities employed in the equations of Fig. 3 do not refer to a specific transport mechanism, but provide an empirical description of the global transport capacity of the membrane for the substance considered.

The system of differential equations of Fig. 3 was solved by numerically solving the Eigenvalues using the MatLab program package (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). A principle used throughout was to avoid calculation of more than two parameters from one type of experiment. In the case of intact mucosa, the extracellular inhibitor STAPTPP was always present, so the parameters determining these recordings (Fig. 5) are intracellular CA activity (Ain) and the permeabilities PCO2 and PHCO3. To determine Ain independently, the following procedure was chosen: isolated colonocytes were measured in suspension without any additions (recordings being determined by Aex, Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3; Fig. 4A, first part); to this suspension Triton X-100 was added later in the experiment to produce complete lysis, which in a semilogarithmic plot gives a linear curve of C18O16O decay (the slope being solely determined by the total, i.e. sum of extracellular and intracellular CA activity of the colonocytes; Fig. 4A, second part); then colonocytes in suspension were studied in the presence of the extracellular CA inhibitor STAPTPP (recordings now being determined by Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3; Fig. 4B). This indicates that it is possible to derive from these data (i) total CA activity and (ii) extracellular activity, the difference giving the intracellular CA activity. All three types of mass spectrometric experiments were subjected to sequential fitting procedures, with the goal to determine the common set of parameter values that gives a best fit for the combined three types of experiments. The results of these calculations are given in Table 1. The intracellular CA activity obtained in this way was then inserted into the fitting procedure by which PCO2 and PHCO3 were calculated from measurements of intact colonic mucosa.

Table 1.

Permeabilities and carbonic anhydrase (CA) activities of isolated epithelial cells from the proximal and distal colon of the guinea pig

| PCO2 | PHCO3 | Ain | Aex | Atot | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | 17 × 10−3 | 10 × 10−4 | 41 000 | 2.5 | 10 | 23 |

| colonocytes | ±9 × 10−3 | ±6 × 10−4 | ±16 000 | ±0.5 | ±3 | |

| Distal | 1.0 × 10−3 | 0.62 × 10−4 | 900 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 14 |

| colonocytes | ±0.9 × 10−3 | ±0.40 × 10−4 | ±630 | ±0.2 | ±0.8 |

PCO2 and PHCO3 are permeabilities of CO2 and HCO3− measured in centimetres per second. Given are means ±s.d.Atot is the total CA activity of isolated colonocytes, intra- plus extracellular CA. Ain is intracellular, Aex is extracellular CA activity. n is the number of mass spectrometric determinations. Temperature was 20°C.

Preparation of intact colon epithelium and of isolated colonocytes

Guinea pigs

Adult female guinea pigs of body weight 550–700 g were fed a pelleted standard diet. Water and food were available ad libitum. The animals were maintained in a 12 h light: 12 h dark photocycle. They were anaesthetized with ether and killed by cervical dislocation between 08.00 and 10.00 h. The procedures conformed with state and federal legislation.

Intact mucosal epithelium

Proximal and distal colon were quickly removed from the guinea pigs, and flushed with ice-cold carbogen-gassed standard reaction solution to remove luminal contents, and then stored in ice-cold carbogen-gassed standard reaction solution. Segments of intact colon (3 cm long) were cut, placed in standard reaction solution, and the muscle layer was manually dissected away using a forceps. The stripped colon epithelium was then checked for visible damage under a stereomicroscope. In several cases, the integrity of the stripped colon was further tested by staining with Trypan Blue before and after mass spectrometry. The colon segments were stained whilst on the Teflon cylinder, then removed from the cylinder, put into liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. From these colon segments, 10 µm thick sections were cut on a cryomicrotome, studied and photographed under the microscope. No visible Trypan Blue entry into the cells was observed either before or after mass spectrometry. The colon segments were inverted before being placed onto the Teflon cylinder, when 18O exchange was to be studied across the apical membrane of the epithelium.

The calculations of Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3 require knowledge of the volume of cell water and of the surface area of the epithelial cells exposed to the reaction mixture. Mucosal surface area was determined morphometrically as decribed before (Böllert et al. 1997a), and was found to be 1.4 times the surface area of the cylinder onto which the piece of colon had been slid in the case of proximal, and 1.5 times in the case of distal colon. A 10% overestimation of the surface area will lead to a 10% underestimation of CO2 as well as HCO3− permeability. The volume of the epithelial cells participating in 18O exchange was obtained by multiplying the epithelial surface area by the average height of the epithelial cells of the mucosa in the proximal and distal parts of the guinea-pig colon (Luciano et al. 1984). The water fraction of these cellular volumes was taken to be 0.85 (Böllert et al. 1997a). It may be noted that the present method actually determines the product of permeability times surface area, such that an underestimation of the area results in an identical overestimation of permeability. In contrast, an error in the cellular water fraction affects both cellular volume and surface-to-volume ratio, and therefore does not influence permeability.

Isolated colonocytes

Immediately after removal of the proximal and the distal colon segments, they were rinsed with standard reaction solution and put on ice. Before the start of trypsinization, the segments were rinsed twice with rinsing buffer followed by two rinses with buffer A. They were then mounted between two tubings and put into a glass vessel filled with carbogen-gassed ice-cold buffer A. The tubing was then perfused by a pump with buffer A, to which 0.125% trypsin had been added, which had been prewarmed to 37°C. During the first 2–3 min, the perfusate leaving the colon segment was discarded, then a closed-loop recirculation of a total buffer A volume of 150 ml continued for 20–30 min. The recirculating solution was gassed continuously. Thereafter trypsinization was rapidly terminated by a first centrifugation at 1000 g for 7 min (0°C) and removal of the supernatant. After resuspension of the pellet in HCO3−-free standard reaction solution, two further centrifugations followed, and all cell pellets were combined. The pellet was weighed and resuspended in standard reaction solution to give the desired cytocrit. An aliquot of the cell suspension was exposed to Trypan Blue, giving a vitality of ∼90%. Another aliquot was used to count the number of cells at the given cytocrit, from which the average cell volume was derived under the assumption that the extracellular space in the pellet comprises 70% of pellet volume (Böllert et al. 1997a). Cell surface of isolated colonocytes was calculated from cell volume assuming spherical shape. The colonocytes were used for mass spectrometric measurements during the subsequent 4 h. Trypan Blue exclusion was found in 80–90% of the cells after the mass spectrometric measurement had been completed. The effect of a 20% loss in intact cells is an underestimation of permeability by ∼20% (because this loss causes a 20% reduction in cellular volume without affecting surface-to-volume ratio).

Results

CA activities and permeabilities of CO2 and HCO3− in isolated colonocytes

Figure 4A shows an 18O-exchange experiment with isolated colonocytes from proximal colon in the absence of CA inhibitor. After the addition of the cells, a biphasic time course was seen, whose first phase was less pronounced than that of Fig. 4B, because in Fig. 4A, but not in Fig. 4b, substantial extracellular CA activity occurs, presumably representing the membrane-bound extracellular CA that has been reported to be present in colon epithelium (Fleming et al. 1995). After addition of Triton X-100 at a final concentration of 0.1%, all CA of the cells was accessible from the extracellular space, yielding a linear time course in the semilogarithmic plot. The ratio of the slope of this linear portion over the slope of the uncatalysed initial part of the recording simply constitutes the total CA activity or acceleration factor exhibited by the lysed colonocytes in the reaction volume of the chamber. The time course of 18O decay observed after addition of cells, before Triton was added, depends on the four parameters Aex, Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3.

Figure 4B gives a recording obtained in the presence of isolated colonocytes preincubated with the extracellular CA inhibitor STAPTPP at a concentration of 10−5m (sufficient to inhibit extracellular CA by >95%). A pronounced biphasic time course was seen which was determined by Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3. The first phase of 18O decay here was greater than in Fig. 4A, because the extracellular CO2 hydration reaction was uncatalysed, i.e. much slower, and therefore competed with the catalysed intracellular CO2 hydration reaction to a much lesser extent than in Fig. 4A.

The three types of experiments: (a) intact cells, (b) cells with Triton X-100, and (c) cells with STAPTPP, were used to calculate Aex, Ain, PCO2 and PHCO3 in the following manner. Data from (a) were used to calculate Aex and Ain after inserting arbitrary estimates of PHCO3 and PCO2. The value of Aex obtained thereby was used to calculate a new estimate of Ain by subtraction from the total colonocyte CA activity (Atot) obtained from experiment (b). This value of Ain was inserted into analysis of experiment (c), yielding new estimates of PCO2 and PHCO3. These values constituted the basis for new guesses of PCO2 and PHCO3 that were inserted into analysis of (a). This cycle of calculations was repeated until the guessed starting values of all parameters agreed with the calculated values obtained from the fitting procedure. This set of parameter values represented the best-fit description of all three types of experiments.

Table 1 gives the parameter values obtained in this way. It may be seen that the HCO3− permeability of proximal colonocytes was >10 times greater than that of distal colonocytes, and both values were in the range of figures reported previously (Böllert et al. 1997a). CO2 permeabilities were >10 times greater than HCO3− permeabilities. While the extracellular CA activities of proximal and distal epithelial cells were similar, the intracellular activities were >40 times greater in the proximal than in the distal epithelium. The intracellular activities of 41 000 for proximal and 900 for distal epithelial cells were used in the following calculations to evaluate data for intact colon epithelium.

CO2 and HCO3− permeabilities of the apical membranes in intact colon epithelium

Figure 5A and B shows original recordings with epithelium from the proximal and distal guinea-pig colon. In all experiments sufficient STAPTPP was present to inhibit all extracellular CA. When the apical side of the epithelia was exposed to the reaction solution, this extracellular CA was substantial in the absence of STAPTPP, which was probably due to residual colonic mucus that possesses high CA activity as shown previously (Böllert et al. 1997a; Kleinke et al. 2005).

Table 2 gives the results of the fitting procedures applied to the data with intact epithelium. Aex was 1 (indicating zero CA activity) due to the presence of the CA inhibitor; Ain values were taken from Table 1. Thus, only the values of PCO2 and PHCO3 given in Table 2 were calculated from these data obtained from intact epithelial sheets. The CO2 permeabilities were 25% to 10 times lower than in isolated colonocytes, whereas HCO3− permeabilities were similar in intact epithelium and in isolated epithelial cells. The differences in PCO2 may reflect different properties of apical and basolateral membranes, as the former are observed in intact epithelium, while a combination of both is observed in isolated colonocytes.

Table 2.

CO2 and HCO3− permeability of the apical membrane of intact guinea-pig colon

| PCO2 | PHCO3 | Ain | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact proximal colon | 1.5 × 10−3 ±0.7 × 10−3 | 6.3 × 10−4 ±4.0 × 10−4 | 41 000 | 40 |

| ±0.7 × 10−3 | ±4.0 × 10−4 | |||

| Intact distal colon | 0.77 × 10−3 ±0.21 × 10−3 | 0.87 × 10−4 ±0.56 × 10−4 | 900 | 23 |

| ±0.21 × 10−3 | ±0.56 × 10−4 |

PCO2 and PHCO3 are measured in centimetres per second. Given are means ±s.d.Ain is from Table 1. Temperature was 20°C.

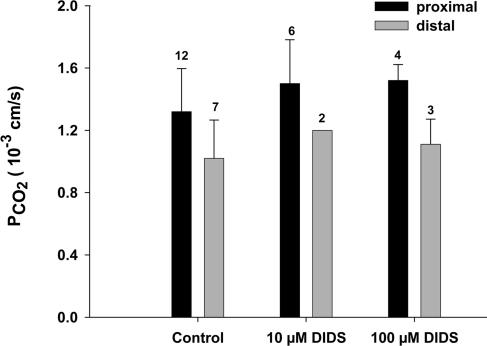

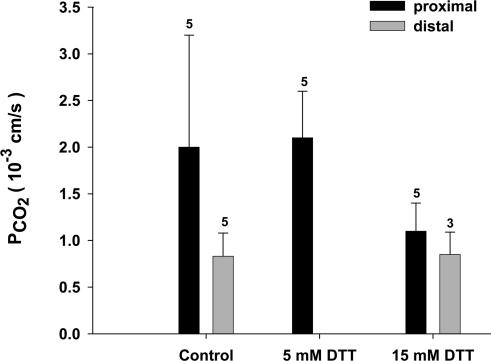

No effects of DTT and DIDS on PCO2

DIDS is an inhibitor of several anion exchange proteins, and in the case of the red cell has been shown to block a CO2 channel that is constituted by AE1 in this membrane (Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). Figure 6 shows that DIDS has no marked effect on PCO2, neither in the distal nor in the proximal colon. This pathway for CO2 that is important in the red cell does not seem to be present in the colon. Figure 7 shows the effects of incubation of the apical sides of proximal and distal colon epithelium with 5 mm or 15 mm DDT. DDT is known to break up native colonic mucus and render the apical surfaces mucus-free (Genz et al. 1999). This was done in order to determine a possible contribution of the mucus layer to the CO2 barrier at the apical side of the colon. Figure 7 shows that in all cases no major deviations from the control values of PCO2 (and PHCO3) are observed.

Figure 6. Effect of DIDS on the CO2 permeabilities of the apical membrane in proximal and distal colon.

DIDS does not cause significant effects on PCO2 at either concentration. HCO3− permeabilities are between 0.5 and 1.2 × 10−3 cm s−1 for controls of proximal, and 0.1 and 0.2 × 10−3 cm s−1 for controls of distal colon, and also exhibit no significant effects of DIDS. Error bars represent standard deviation values, numbers represent n values.

Figure 7. Effect of dithiotreitol (DTT) on the CO2 permeabilities of the apical membrane in proximal and distal colon.

DTT does not cause a significant effect on PCO2 at either concentration. HCO3− permeabilities are 0.7 × 10−3 cm s−1 for controls of proximal and 0.12 × 10−3 cm s−1 for controls of distal colon, and also exhibit no significant effects of DTT. Error bars represent standard deviation values, numbers represent n values.

Discussion

Epithelial CA activities

Intracellular CA

This parameter is of crucial importance as it is used here to determine PCO2 from the mass spectrometric measurements with intact stripped mucosa. Its determination depends on the impermeabilities of the isolated colonocytes and the intact stripped colonic epithelium to the CA inhibitor STAPTPP. This has been tested with red cells and colonocytes, which both show no dependence of intracellular CA activity for a time of exposure to STAPTPP up to at least 40 min, a period that markedly exceeds the time of exposure occurring in the mass spectrometer experiments. It should be noted that the intracellular activities given in Table 1 are 7–80 times greater than those reported previously (Böllert et al. 1997a). This is essentially due to the fact that the algorithm previously used to determine Ain and PHCO3 was based on the assumption that PCO2 is infinite and does not limit overall 18O exchange (Böllert et al. 1997a; Itada & Forster, 1977). In the equation system of Fig. 3, this assumption is no longer made and CO2 fluxes are correctly treated in terms of the CO2 permeability of the cell membrane (Wunder et al. 1997; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). In the previous algorithm, an entry of CO2 into the cell that is slowed by a diffusion resistance of the membrane was interpreted as a reduced intracellular CA activity. Therefore, the much higher CA activies of Table 1 represent the correct values; in the case of proximal colon, the activity is even greater than the CA activity in the human red cell. It may be noted that the lower values reported by Böllert et al. (1997a) would not add up to the total CA activities measured in the present study in the presence of Triton (Table 1).

The approximately 40 times higher CA activity seen in Table 1 for the proximal colon compared with the distal colon agrees qualitatively with earlier reports (Carter & Parsons 1970a, b; Lönnerholm, 1977), which found that cytosolic CA activity is greater in the proximal than in the distal colon of the guinea pig.

Extracellular CA activity

The data of Table 1 show that both proximal and distal colonocytes possess substantial extracellular CA activity. This is in qualitative agreement with immunocytochemical results of Fleming et al. (1995), who report high levels of extracellular apical CA IV in rat and human colonic epithelium. In addition, some membrane-bound CA IX has been observed in the mouse colon (Hilvo et al. 2004). In intact epithelium, the apical extracellular CA activity could not be measured, as all experiments were carried out in the presence of STAPTPP.

Epithelial HCO3− permeability

HCO3− permeability of isolated colonocytes

The values of proximal and distal PHCO3 in Table 1 are both somewhat higher than the values of 1 × 10−4 cm s−1 and 0.2 × 10−4 cm s−1 that we have reported previously for guinea-pig colonocytes (Böllert et al. 1997a), which is due to the improved mathematical model. The present values reflect a markedly greater transport capacity for bicarbonate in the proximal than in the distal colon. In both cases, the permeabilities are similar to those reported in Table 2 for the apical membrane. This would suggest that HCO3− permeabilities are similar in the basolateral and apical epithelial cell membranes.

HCO3− permeability of the apical membrane

It is noteworthy that apical PHCO3 is 10 times greater in the proximal than in the distal colon (Table 2). In both colon segments the apical membranes possess Cl−–HCO3− exchange activity (Mahajan et al. 1996; Rajendran et al. 2000; Vidyasagar et al. 2004; Charney et al. 2004) and an exchange mechanism of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) against HCO3− (Mascolo et al. 1991; Vidyasagar et al. 2004). Because in the proximal colon a major fraction of SCFA is transported by exchange for HCO3−, while in the distal colon a majority of SCFAs are absorbed by diffusion of the undissociated form (von Engelhardt & Rechkemmer, 1992; von Engelhardt et al. 1993, 1994), the overall transport capacity for HCO3− may have to be much greater in the apical membrane of the proximal colon than of the distal colon. In addition, the difference may reflect the fact that absorptive fluxes generally are larger in the proximal than in the distal colon.

It may be noted that in the present mass spectrometric experiments there is chemical equilibrium between H+, HCO3− and CO2, and equilibrium between intra- and extracellular spaces at all times. Thus no net fluxes of total HCO3− and CO2 can occur. However, gradients exist for the 18O-labelled species HCO3− and CO2, and identical gradients of unlabelled HCO3− and CO2 of an opposite sign. Thus, the Cl−–HCO3− exchanger is expected to operate in the mode of HC18O16O2–HC16O3− self-exchange, and the SCFA–HCO3− exchanger may operate in both directions with zero net flux of SCFA and fluxes of labelled HCO3− in one, and unlabelled HCO3− in the other direction.

Epithelial CO2 permeability

CO2 permeability of isolated colonocytes

The values of 17 × 10−3 cm s−1 for proximal and 1.0 × 10−3 cm s−1 for distal colonocytes are 20–300 times lower than the value measured by the same technique for the CO2 permeability of the red cell, i.e. 0.3 cm s−1 (Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). It thus appears that the membrane resistance towards CO2 is much greater in colon epithelial membranes than in the red cell membrane, where it appears to be exceptionally low. Table 1 shows that there is a considerable, and statistically significant, 17-fold difference between proximal and distal PCO2 values, although the distal value is rather uncertain.

CO2 permeability of the apical membrane

The apical CO2 permeability of the distal colon, 0.77 × 10−3 cm s−1, is about two times lower than that of the proximal colon, 1.5 × 10−3 cm s−1 (Table 2). More importantly, both values are ≥200 times lower than PCO2 of the red cell membrane (Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). The absolute permeabilities of the apical membranes are subject to some uncertainty because only a rough estimate of the effective apical surface area of the epithelium is employed. In this estimate, we neglect entirely the surface enhancement by the microvilli, which, if taken into account, would further reduce the calculated PCO2. It can be concluded that, in spite of these uncertainties, the apical CO2 permeability appears to be far lower than the PCO2 of red cells. Thus, while the membrane of the red cells is apparently optimized in terms of its CO2 permeability, the apical membranes of the proximal as well as the distal colon constitute a significant barrier for the permeation of CO2.

Possible role of unstirred layers

It may be asked, whether the low CO2 permeability can be an artifact due to an unstirred layer covering the apical membranes of the epithelium, or the colonocyte membranes, respectively. This might cause an apparent low membrane permeability. If the true apical CO2 permeability were the same as that of the red cell, 0.3 cm s−1, offering a diffusion resistance of 1/0.3 s cm−1, an unstirred water layer (lH2O) of 113 µm thickness would produce a resistance in series to that of the membrane of lH2O/DCO2= 0.0113/1.7 × 10−5 cm s cm−2= 664 s cm−1 (DCO2 from Gros & Moll, 1971). The resistances of the membrane and the water layer would add up to 667 s cm−1, and this total resistance would correspond to a permeability value of 1.5 × 10−3 cm s−1, the value measured for the apical membrane of the proximal colon. In the case of proximal colonocytes, the analogous calculation leads to an unstirred layer of 9.4 µm, which corresponds about to the diameter of these cells (∼10–20 µm). In other words, 113 µm and 9.4 µm of unstirred water layer, respectively, would then be necessary to explain the very low PCO2 values observed.

We exclude this possibility in view of recent results with human red cells using the same technique (Wunder et al. 1997; Forster et al. 1998; Endeward et al., in preparation). The experiments with red cells were conducted under conditions identical to those for colonocytes, and yielded the much higher permeability value of 0.3 cm s−1. Even if this figure is interpreted to represent entirely the resistance of an unstirred layer (assuming that the membrane exhibits zero resistance), an unstirred layer thickness lH2O of no more than DCO2/PCO2= 1.7 × 10−5/0.3 cm = 0.6 µm is postulated. This is 16 times less than the unstirred layer thickness that would have to be postulated in the case of colonocytes, and 180 times less than the unstirred layer thickness postulated for intact colon epithelium. It is unlikely that identical stirring conditions produce dramatically different unstirred layers in red cells and in isolated colonocytes. The very high permeability of the red cell membrane suggests therefore that analysis of the 18O experiments is not affected by insufficient stirring in the present technique. This lack of an effect of the unstirred layers, although expected to be present to some extent, may be attributed to the fact that in the fluid immediately surrounding the cells – as in the rest of the extracellular fluid – there is ∼20 times more (labelled) HCO3− than CO2, providing a large reservoir for the replenishment of CO2 that has diffused into the cell. Thus, the insensitivity of the present method to unstirred layers seems to reflect a special property of gaseous CO2 dissolved in water.

Apical versus basolateral CO2 permeability

The CO2 permeability of the membrane of the isolated proximal colonocyte (17 × 10−3 cm s−1; Table 1) is 10 times greater compared to that of the proximal apical membrane (1.5 × 10−3 cm s−1; Table 2). This very likely is due to different CO2 permeabilities of the apical and basolateral membranes of these cells. When the apical and basolateral portions are assumed to constitute 25% and 75% of the colonocyte membrane, respectively, and behave towards CO2 diffusion as resistances in parallel, these figures can be explained quantitatively by a baslolateral PCO2 of 22 × 10−3 cm s−1 together with an apical PCO2 of 1.5 × 10−3 cm s−1. This would imply a 14 times greater PCO2 in the basolateral than in the apical membrane, and would be in qualitative agreement with the previous observation that the basolateral membrane exhibits a much greater permeability to NH3 than the apical membrane (Singh et al. 1995). In the distal colon, this difference would be smaller, suggesting that the basolateral membrane of distal colon may have a similarly low CO2 permeability as the apical membrane; however, the standard deviation of the experimental data for distal colonocytes is far greater (Table 1).

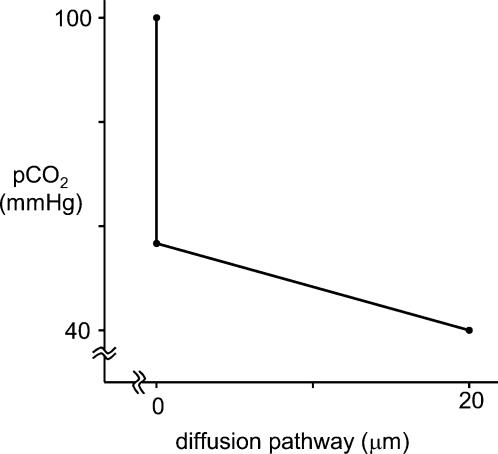

Physiological consequence of the apical CO2 barrier

What follows from the high resistance of the apical membrane for the gradient of pCO2 across the epithelial cell when a high luminal CO2 occurs in conjunction with a normal capillary pCO2 of 40 mmHg? The parameters determining this gradient are the diffusion resistances constituted by the apical membrane (Rap) and by the interior of the epithelial cell (Rcell). The former is given by the apical permeability:

| (1) |

which in the case of proximal intact colon is:

| (2) |

The latter resistance is given by the height h of the epithelial cell, taken to be 20 µm, and by the intracellular CO2 diffusion coefficient, DCO2, that is estimated from the data compiled by Gros & Moll (1971) for various tissues to be 8.1 × 10−6 cm s−1:

| (3) |

In other words, in the proximal colon the apical membrane constitutes 73% (84% in the distal colon) of the total resistance of the epithelial cell towards CO2 diffusion. Accordingly, the apical membrane will be responsible for 73 or 84% of a pCO2 gradient existing between colonic lumen and capillary. This is visualized for proximal colon in Fig. 8, which shows the pCO2 gradient as calculated from these data when luminal pCO2 is 100 mmHg and capillary pCO2 is 40 mmHg. It is apparent that the cell interior is not exposed to most of the high luminal CO2 level, i.e. the cell interior is ‘protected’ against high luminal pCO2 by the apical gas barrier. It is evident that, under even higher pCO2 levels of up to 0.5 atm (50.66 kPa) as they may occur in the lumen of the colon (Rasmussen et al. 1999, 2002), this protective effect of the apical membrane saves the cell quite effectively from an extreme load of volatile acid. It may be noted that the barrier visualized in Fig. 8, while very markedly reducing the pCO2 acting on the cell, does not make the cell impermeable to CO2 and still allows significant CO2 absorption rates.

Figure 8. The CO2 partial pressure gradient across the epithelial cell, as calculated with the known diffusion resistance of the cell interior and the resistance of the apical membrane, as determined here.

Assumed are a luminal pCO2 of 100 mmHg and a capillary (basal) pCO2 of 40 mmHg.

A breakdown of this CO2 barrier may have an important pathophysiological role in chronic colonic inflammation. For urinary bladder, Lavelle et al. (1998) have shown that a moderate inflammation elicited immunologically can damage several elements of the epithelial barrier, such as disruption of tight junctions and loss of apical membrane architecture. When this is associated with enhanced access of high luminal CO2 partial pressures to the intracellular epithelial spaces, the ensuing cellular acid load may exacerbate inflammation and damage of the epithelium. Thus, an incipient inflammation may be aggravated by the diminished self-protection of the epithelial cells against CO2 and possibly other gases. An analogous mechanism is conceivable for ammonia, which can also occur in high concentrations in the colon and the stomach.

Nature of the apical gas barrier

Several possibilities have to be considered that might contribute to the high apical diffusion resistance observed in the present experiments. Firstly, the possible function of the colonic mucus as CO2 barrier has to be discussed. We have recently shown, on the basis of a theoretical model (Endeward et al. 2003), that colonic mucus can keep the pCO2 on the epithelial surface low even though the luminal pCO2 is high. This is brought about by the following properties of colonic mucus: (1) it possesses high activities of a distinct mucus CA (Kleinke et al. 2005), (2) it exhibits a high proton buffer capacity (Schreiber & Scheid, 1997), and (3) it is secreted from the epithelium and therefore moves continuously from the epithelial surface towards the lumen. These three properties would tend to cause a fall in pCO2 cross the apical mucus layer in the following way: (i) CO2 diffuses from the lumen into the mucus layer, where due to the high CA activity it is rapidly hydrated to give HCO3− and H+; (ii) H+ is bound by the mucus; and (iii) both HCO3− and buffered H+ move along with the flow of mucus towards the lumen. This represents convectional transport of the two species. Thus, because the reaction products of CO2 hydration are effectively removed from the epithelial surface, pCO2 will for reasons of chemical equilibrium remain low on the epithelial surface. The quantitative contribution of this mechanism depends on the rate of mucus production and flow. We have attempted here to experimentally test the significance of this mechanism by breaking up the mucus with DTT, which is followed by loss of the mucus layer. It is not clear, however, how much mucus was present on the colon mucosa before the exposure to DTT was started. As seen in Fig. 7, DTT treatment did not result in a change in the measured apical PCO2. This suggests that under the present experimental conditions mucus does not significantly contribute to the low PCO2 of the apical face of the epithelium.

It has previously been shown that aquaporin 1 acts as a CO2 channel and that both aquaporin 1 and anion exchanger 1 contribute to the high CO2 permeability of the red cell membrane (Nakhoul et al. 1998; Cooper & Boron, 1998; Forster et al. 1998; V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations). Conversely, absence of these proteins from the membrane may be expected to result in a low CO2 permeability. While an apical anion exchanger has also been reported for the apical membrane of the proximal colon (Mahajan et al. 1996), the anion exchanger 1 has only been identified in apical membranes of crypt cells of the distal colon (Rajendran et al. 2000). The presence of aquaporin 1 in colon epithelium is controversial; it has been localized to the apical epithelial membrane in human colon by Hasegawa et al. (1994) and in Octodon degus colon by Gallardo et al. (2002), but has been reported to be entirely absent from the epithelial membranes in rat colon (Nielsen et al. 1993). In contrast to the apical membrane, the basolateral membrane of rat colonic and rectum surface epithelium expresses aquaporin 3 abundantly (Matsuzaki et al. 1999, 2004; Kierbel et al. 2000). It appears possible, therefore, that the apical (and also the basolateral) membranes of colon epithelium lack aquaporin 1, which is the only aquaporin isoform that has been associated with CO2 transport. Thus, at least the apical membrane of the proximal colon may not have any CO2 transporting protein at all. This is in accordance with the low PCO2 value observed here, and with the lack of an effect of DIDS on apical CO2 permeability of proximal colon (Fig. 6). However, as may be noted from Fig. 6, we also observe no effect of DIDS on apical PCO2 in distal colon.

The absolute apical CO2 permeability measured here, ∼0.001 cm s−1, is one order of magnitude lower than the pCO2 value reported by Endeward et al. (V. Endeward, L. Virkki, L. S. King, C. T. Supuram, W. F. Bordu and G. Gros, unpublished observations) for aquaporin-1-deficient red cells whose anion exchanger 1 was inhibited by DIDS, and which thus possessed neither of the two CO2 channels in an active state. The resistance of the apical membranes of the colon might be increased by a special composition of their membrane lipids. Busche et al. (2002) have shown that apical membrane vesicles from the proximal colon exhibit a greater resistance towards the permeation of neutral (protonated) SCFA than basolateral membrane vesicles. This difference could not be attributed to the differences in cholesterol content, but other lipid components were not determined. Hill & Zeidel (2000) have shown that vesicles whose composition imitates the exofacial membrane leaflet of the apical membrane of a barrier epithelium, Madin-Darby canine kidney type 1 cells, have an ∼80 times lower permeability for gaseous NH3 than vesicles modelling the cytoplasmic leaflet of these membranes. This shows that lipid composition can make a very marked difference in gas permeability. Whether this holds also for molecular CO2 has yet to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for support of this project under SFB 280/261 (Project C05). We are indebted to Frau Sisko Bauer and Frau Stephanie Reuß for expert technical assistance. We thank Professor W. von Engelhardt and Dr R. Busche (Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover) for frequent advice and stimulating discussions. We are grateful to Professor Robert E. Forster (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) for most helpful discussions of basic aspects of the 18O exchange method.

References

- Böllert P, Peters T, Gros G. Determination of intracellular carbonic anhydrase activity and bicarbonate permeability in intact colon epithelia by observation of the 18O-labelling of CO2. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 1997b;33:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Böllert P, Peters T, von Engelhardt W, Gros G. Mass spectrometric determination of HCO3− permeability and carbonic anhydrase activity in intact guinea-pig colon epithelium. J Physiol. 1997a;502:679–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.679bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF, Waisbren SJ, Modlin IM, Geibel JP. Unique permeability barrier of the apical surface of parietal and chief cells in isolated perfused gastric glands. J Exp Biol. 1994;196:347–360. doi: 10.1242/jeb.196.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche R, Dittmann J, Meyer zu Düttingdorf HD, Glockenthör U, von Engelhardt W, Sallmann HP. Permeability properties of apical and basolateral membranes of the guinea pig caecal and colonic epithelia for short-chain fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1565:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MJ, Parsons DS. The carbonic anhydrase of some guinea-pig tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970a;206:190–192. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(70)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MJ, Parsons DS. The purification and properties of carbonic anhydrases from guinea-pig erythrocytes and mucosae of the gastrointestinal tract. Biochem J. 1970b;120:797–808. doi: 10.1042/bj1200797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney AN, Egnor RW, Henner D, Rashid H, Cassai N, Sidhu GS. Acid–base effects on intestinal Cl− absorption and vesicular trafficking. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1062–1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00454.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GJ, Boron WF. Effect of PCMBS on CO2 permeability of Xenopus oocytes expressing aquaporin 1 or its C189S mutant. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;275:C1481–1486. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward V, Kleinke T, Gros G. Carbonic anhydrase in the gastrointestinal mucus of mammals. Possible protective role against carbon dioxide. Comp Biochem Physiol. 2003;136:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt W, Burmester M, Hansen K, Becker G, Rechkemmer G. Effects of amiloride and ouabain on short-chain fatty acid transport in guinea-pig large intestine. J Physiol. 1993;460:455–466. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt W, Gros G, Burmester M, Hansen K, Becker G, Rechkemmer G. Functional role of bicarbonate in propionate transport across guinea-pig isolated caecum and proximal colon. J Physiol. 1994;477:365–371. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt W, Rechkemmer G. Segmental differences of short-chain fatty acid transport across guinea-pig large intestine. Exp Physiol. 1992;77:491–499. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1992.sp003609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming RE, Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Rajaniemi H, Waheed A, Sly WS. Carbonic anhydrase IV expression in rat and human gastrointestinal tract regional, cellular, and subcellular localization. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2907–2913. doi: 10.1172/JCI118362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster RE, Gros G, Lin L, Ono Y, Wunder M. The effect of 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonate on CO2 permeability of the red blood cell membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15815–15820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo P, Olea N, Sepulveda V. Distribution of aquaporins in the colon of Octodon degus, a South American desert rodent. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R779–788. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00218.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genz AK, von Engelhardt W, Busche R. Maintenance and regulation of the pH microclimate at the luminal surface of the distal colon of guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1999;517:507–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0507t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros G, Moll W. The diffusion of carbon dioxide in erythrocytes and hemoglobin solutions. Pflugers Arch. 1971;324:249–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00586422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Lian SC, Finkbeiner WE, Verkman AS. Extrarenal tissue distribution of CHIP28 water channels by in situ hybridization and antibody staining. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1994;266:C893–903. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.4.C893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WG, Zeidel ML. Reconstituting the barrier properties of a water-tight epithelial membrane by design of leaflet-specific liposomes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30176–30185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilvo M, Rafajova M, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Parkkila S. Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX in mouse tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:1313–1322. doi: 10.1177/002215540405201007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itada N, Forster RE. Carbonic anhydrase activity in intact red blood cells measured with 18O exchange. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:3881–3890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierbel A, Capurro C, Pisam M, Gobin R, Christensen BM, Nielsen S, Parisi M. Effects of medium hypertonicity on water permeability in the mammalian rectum: ultrastructural and molecular correlates. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s004240000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikeri D, Sun A, Zeidel L, Hebert SC. Cell membranes impermeable to NH3. Nature. 1989;339:478–480. doi: 10.1038/339478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinke T, Wagner S, John H, Hewett-Emmett D, Parkkila S, Forssmann WG, Gros G. A distinct carbonic anhydrase in the mucus of the colon of humans and other mammals. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:487–496. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle JP, Apodaca G, Meyers SA, Ruiz WG, Zeidel ML. Disruption of guinea pig urinary bladder permeability barrier in noninfectious cystitis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F205–214. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.1.F205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Visek W. Large intestinal pH and ammonia in rats: dietary fat and protein interactions. J Nutr. 1991;121:832–843. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.6.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnerholm G. Carbonic anhydrase in the intestinal tract of the guinea pig. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;99:53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnerholm G, Midtvedt T, Schenholm M, Wistrand PJ. Carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes in the caecum and colon of normal and germ-free rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1988;132:159–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1988.tb08313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano L, Reale E, Rechkemmer G, von Engelhardt W. Structure of zonulae occludentes and the permeability of the epithelium to short-chain fatty acids in the proximal and the distal colon of guinea-pig. J Membr Biol. 1984;82:145–156. doi: 10.1007/BF01868939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan RJ, Baldwin ML, Harig JM, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. Chloride transport in human proximal colonic apical membrane vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1280:12–18. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascolo N, Rajendran VM, Binder HJ. Mechanism of short-chain fatty acid uptake by apical membrane vesicles of rat distal colon. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki T, Suzuki T, Koyama H, Tanaka S, Takata K. Water channel protein AQP3 is present in epithelia exposed to the environment of possible water loss. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1275–1286. doi: 10.1177/002215549904701007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki T, Tajika Y, Ablimit A, Aoki T, Hagiwara H, Takata K. Aquaporins in the digestive system. Med Electron Microsc. 2004;36:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s00795-004-0246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhoul NL, Davis BA, Romero MF, Boron WF. Effect of expressing the water channel aquaporin-1 on the CO2 permeability of Xenopus oocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C543–548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete HO, Lavelle JP, Berg J, Lewis SA, Zeidel ML. Permeability properties of the intact mammalian bladder epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1996;271:F886–894. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.4.F886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Smith BL, Christensen EI, Agre P. Distribution of the aquaporin CHIP in secretory and resorptive epithelia and capillary endothelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7275–7279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran VM, Black J, Ardito TA, Sangan P, Alper SL, Schweinfest C, Kashgarian M, Binder HJ. Regulation of DRA and AE1 in rat colon by dietary Na depletion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G931–942. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H, Kvarstein G, Johnsen H, Dirven H, Midtvedt T, Mirtaheri P, Tønnessen TI. Gas supersaturation in the cecal wall of mice due to bacterial CO2 production. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1311–1318. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H, Mirtaheri P, Dirven H, Johnsen H, Kvarstein G, Tønnessen TI, Midtvedt T. PCO2 in the large intestine of mice, rats, guinea pigs, and dogs and effects of the dietary substrate. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:219–224. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00190.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers R, Blanchard A, Eladari D, Leviel F, Paillard M, Podevin R-A, Zeidel ML. Water and solute permeabilities of medullary thick ascending limb apical and basolateral membranes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F453–462. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.3.F453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S, Scheid P. Gastric mucus of the guinea pig: proton carrier and diffusion barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1997;272:G63–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.1.G63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Binder HJ, Geibel JP, Boron WF. An apical permeability barrier to NH3/NH4+ in isolated, perfused colonic crypts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11573–11577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieger B, Marxer A, Hauri HP. Isolation of brush-border membranes from rat and rabbit colonocytes - is alkaline phosphatase a marker enzyme. J Membr Biol. 1986;91:19–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01870211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar S, Rajendran VM, Binder HJ. Three distinct mechanisms of HCO3− secretion in rat distal colon. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C612–621. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00474.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisbren SJ, Geibel JP, Modlin IM, Boron WF. Unusual permeability properties of gastric gland cells. Nature. 1994;368:332–335. doi: 10.1038/368332a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder M, Böllert P, Gros G. Mathematical modelling of the role of intra- and extracellular activity of carbonic anhydrase and membrane permeabilities of HCO3−, H2O, and CO2 on 18O exchange. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 1997;33:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder M, Gros G. 18O exchange in suspensions of red blood cells: determination of parameters of mass spectrometer inlet system. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 1998;34:303–310. doi: 10.1080/10256019808234064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]