Abstract

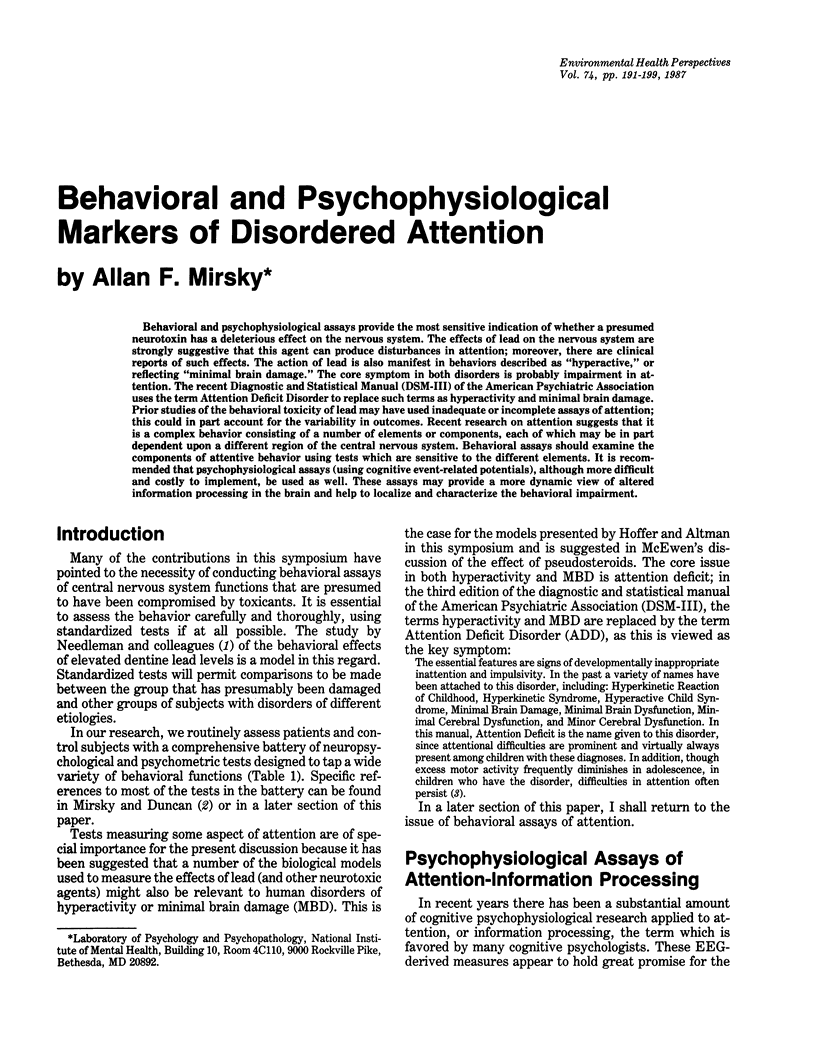

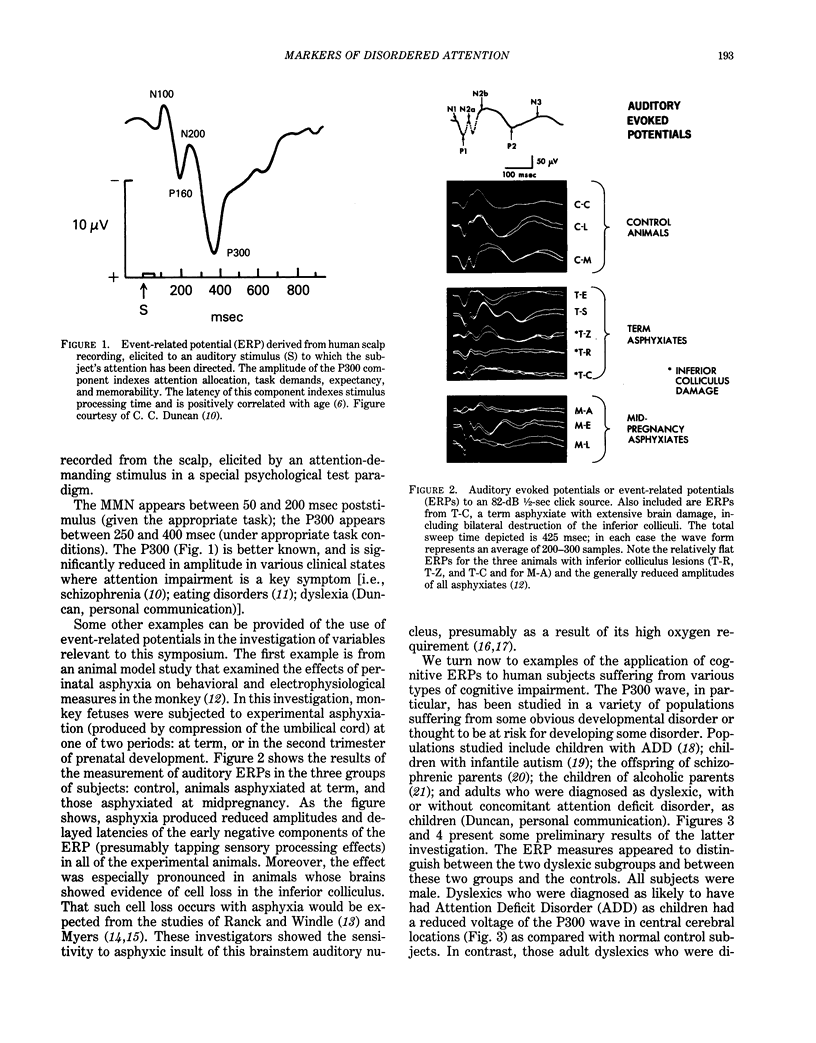

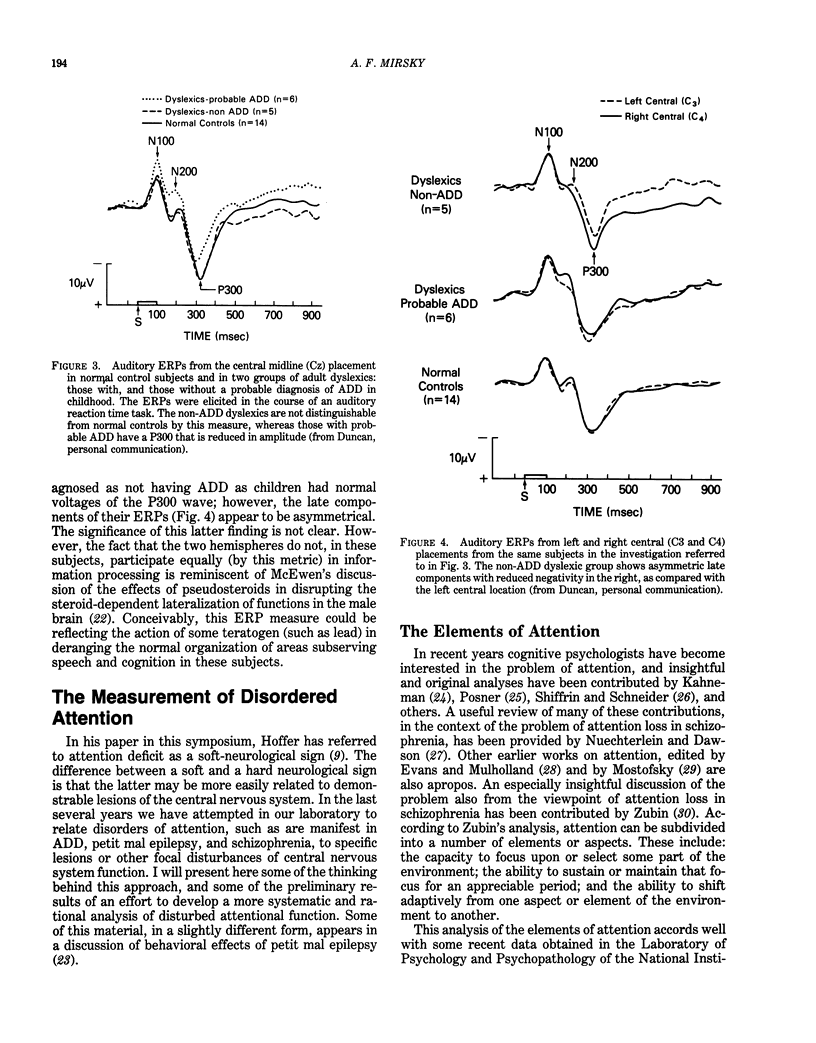

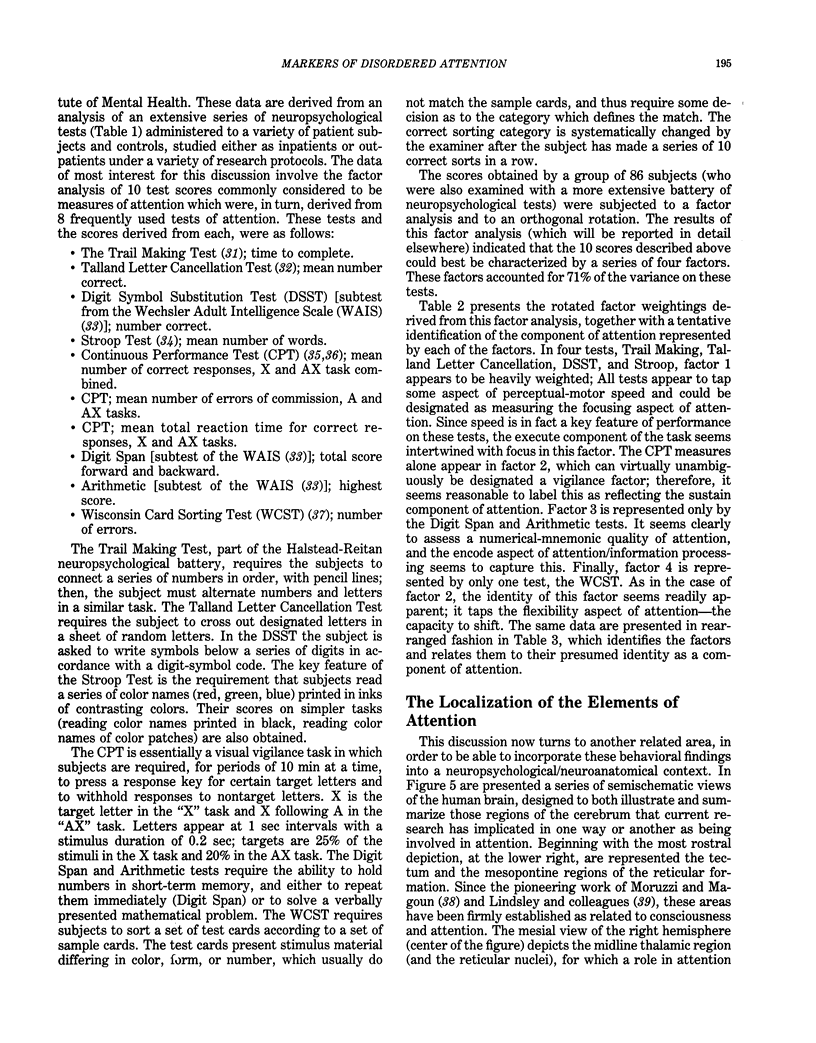

Behavioral and psychophysiological assays provide the most sensitive indication of whether a presumed neurotoxin has a deleterious effect on the nervous system. The effects of lead on the nervous system are strongly suggestive that this agent can produce disturbances in attention; moreover, there are clinical reports of such effects. The action of lead is also manifest in behaviors described as "hyperactive," or reflecting "minimal brain damage." The core symptom in both disorders is probably impairment in attention. The recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III) of the American Psychiatric Association uses the term Attention Deficit Disorder to replace such terms as hyperactivity and minimal brain damage. Prior studies of the behavioral toxicity of lead may have used inadequate or incomplete assays of attention; this could in part account for the variability in outcomes. Recent research on attention suggests that it is a complex behavior consisting of a number of elements or components, each of which may be in part dependent upon a different region of the central nervous system. Behavioral assays should examine the components of attentive behavior using tests which are sensitive to the different elements. It is recommended that psychophysiological assays (using cognitive event-related potentials), although more difficult and costly to implement, be used as well. These assays may provide a more dynamic view of altered information processing in the brain and help to localize and characterize the behavioral impairment.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ajmone Marsan C. The thalamus. Data on its functional anatomy and on some aspects of thalamo-cortical integration. Arch Ital Biol. 1965 Dec 10;103(4):847–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. Morphological and behavioral markers of environmentally induced retardation of brain development: an animal model. Environ Health Perspect. 1987 Oct;74:153–168. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8774153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECK L. H., BRANSOME E. D., Jr, MIRSKY A. F., ROSVOLD H. E., SARASON I. A continuous performance test of brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1956 Oct;20(5):343–350. doi: 10.1037/h0043220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H., Porjesz B., Bihari B., Kissin B. Event-related brain potentials in boys at risk for alcoholism. Science. 1984 Sep 28;225(4669):1493–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.6474187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E., Lincoln A. J., Kilman B. A., Galambos R. Event-related brain potential correlates of the processing of novel visual and auditory information in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1985 Mar;15(1):55–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01837899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Johnson C. C., Donchin E. The P300 component of the event-related brain potential as an index of information processing. Biol Psychol. 1982 Feb-Mar;14(1-2):1–52. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(82)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D., Cornblatt B., Vaughan H., Jr, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Event-related potentials in children at risk for schizophrenia during two versions of the continuous performance test. Psychiatry Res. 1986 Jun;18(2):161–177. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E., Squires N. K., Wilson C. L., Rohrbaugh J. W., Babb T. L., Crandall P. H. Endogenous potentials generated in the human hippocampal formation and amygdala by infrequent events. Science. 1980 Nov 14;210(4471):803–805. doi: 10.1126/science.7434000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healton E. B., Navarro C., Bressman S., Brust J. C. Subcortical neglect. Neurology. 1982 Jul;32(7):776–778. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.7.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer B. J., Olson L., Palmer M. R. Toxic effects of lead in the developing nervous system: in oculo experimental models. Environ Health Perspect. 1987 Oct;74:169–175. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8774169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klorman R., Salzman L. F., Bauer L. O., Coons H. W., Borgstedt A. D., Halpern W. I. Effects of two doses of methylphenidate on cross-situational and borderline hyperactive children's evoked potentials. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983 Aug;56(2):169–185. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANSDELL H., MIRSKY A. F. ATTENTION IN FOCAL AND CENTRENCEPHALIC EPILEPSY. Exp Neurol. 1964 Jun;9:463–469. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(64)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRSKY A. F., PRIMAC D. W., MARSAN C. A., ROSVOLD H. E., STEVENS J. R. A comparison of the psychological test performance of atients with focal and nonfocal epilepsy. Exp Neurol. 1960 Feb;2:75–89. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(60)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRSKY A. F., VANBUREN J. M. ON THE NATURE OF THE "ABSENCE" IN CENTRENCEPHALIC EPILEPSY: A STUDY OF SOME BEHAVIORAL, ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHIC AND AUTONOMIC FACTORS. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1965 Mar;18:334–348. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(65)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. Steroid hormones and brain development: some guidelines for understanding actions of pseudohormones and other toxic agents. Environ Health Perspect. 1987 Oct;74:177–184. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8774177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky A. F., Duncan C. C. An introduction to modern techniques of clinical neuropsychology. Adv Psychosom Med. 1987;17:167–184. doi: 10.1159/000414012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky A. F., Orren M. M., Stanton L., Fullerton B. C., Harris S., Myers R. E. Auditory evoked potentials and auditory behavior following prenatal and perinatal asphyxia in rhesus monkeys. Dev Psychobiol. 1979 Jul;12(4):369–379. doi: 10.1002/dev.420120411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman H. L., Gunnoe C., Leviton A., Reed R., Peresie H., Maher C., Barrett P. Deficits in psychologic and classroom performance of children with elevated dentine lead levels. N Engl J Med. 1979 Mar 29;300(13):689–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903293001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K. H., Dawson M. E. Information processing and attentional functioning in the developmental course of schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(2):160–203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANCK J. B., Jr, WINDLE W. F. Brain damage in the monkey, macaca mulatta, by asphyxia neonatorum. Exp Neurol. 1959 Jun;1(2):130–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(59)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REITAN R. M., TARSHES E. L. Differential effects of lateralized brain lesions on the trail making test. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1959 Sep;129:257–262. doi: 10.1097/00005053-195909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reivich M., Jehle J., Sokoloff L., Kety S. S. Measurement of regional cerebral blood flow with antipyrine-14C in awake cats. J Appl Physiol. 1969 Aug;27(2):296–300. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]