Abstract

The calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) provides a fundamental mechanism for diverse cells to detect and respond to modulations in the ionic and nutrient compositions of their extracellular milieu. The roles for this receptor are largely unknown in the intestinal tract, where epithelial cells are normally exposed to large variations in extracellular solutes. Here, we show that colonic CaSR signaling stimulates the degradation of cyclic nucleotides by phosphodiesterases and describe the ability of receptor activation to reverse the fluid and electrolyte secretory actions of cAMP- and cGMP-generating secretagogues, including cholera toxin and heat stable Escherichia coli enterotoxin STa. Our results suggest a paradigm for regulation of intestinal fluid transport where fine tuning is accomplished by the counterbalancing effects of solute activation of the CaSR on neuronal and hormonal secretagogue actions. The reversal of cholera toxin- and STa endotoxin-induced fluid secretion by a small-molecule CaSR agonist suggests that these compounds may provide a unique therapy for secretory diarrheas.

Keywords: cholera, diarrhea, STa toxin, quanylin, forskolin

The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR; ref. 1) is an ancient G protein-coupled cell surface receptor that is expressed in diverse tissues in mammalian (2) and marine (3) species and is a key regulator of organismal responses crucial for calcium homeostasis (4), salt and water balance (5, 6), and osmotic regulation (3). The primary physiological ligand for the CaSR is extracellular ionized calcium, providing a mechanism for calcium to function as a first messenger. The CaSR also functions as a more general sensor of the extracellular milieu due to allosteric modification of calcium affinity by polyamines, l-amino acids, pH and ionic strength (7). Epithelial cells along the entire length of the intestine express the CaSR (8–10); however, the functions of this receptor in the gastrointestinal tract are only beginning to be understood (11). The CaSR has been identified on both the luminal and basolateral sides of human (10, 12) and rat colonocytes (8, 10), and receptors on both sides of this polarized epithelium can be activated by extracellular calcium and other polycations like spermine (9, 10). CaSR activation of Gq in colonocytes (10), as well as other cell types (2), results in a rise in intracellular Ca2+ via activation of phospholipase C (PLC), formation of IP3, and subsequent Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive cytosolic stores (10).

Previous observations that the CaSR could modulate cyclic nucleotide metabolism in the kidney thick ascending limb and parathyroid gland chief cells (2, 13) suggested that the CaSR might be a potent general regulator of cyclic nucleotide-dependent electrolyte transport in intestinal epithelia. Intestinal fluid and electrolyte losses resulting from Vibrio cholerae cholera toxin (CTX; cholera) and Escherichia coli heat stable enterotoxin (STa; traveler's or epidemic infant diarrhea) remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially in developing countries or after natural disasters (14, 15). CTX is a potent activator of membrane bound adenylyl cyclase leading to elevated intracellular levels of cAMP (14, 16), whereas STa enhances cGMP accumulation through activation of the guanylyl cyclase C-type guanylin receptor (17). Reducing the life-threatening intestinal fluid loss in toxin-induced diarrheas remains a major challenge.

Results

Extracellular Ca2+ or the Small-Molecule CaSR Agonist, R-568, Abrogates Secretagogue-Induced Fluid Secretion.

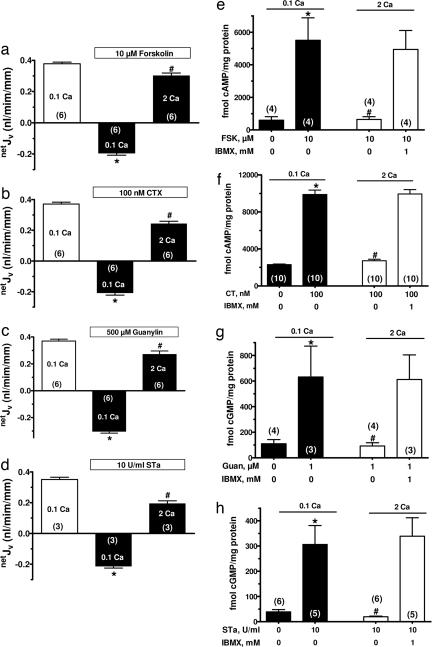

Cyclic nucleotide-dependent fluid loss in secretory diarrheas occurs through reductions in absorptive, and increases in secretory, processes (18, 19). Colonic epithelial crypts provide a model for understanding intestinal fluid transport as they simultaneously absorb and secrete fluid with the direction of net fluid movement (netJV) depending on the relative magnitudes of these two processes (9, 20). To study the effects of CaSR activation on responses of the intestine to bacterial secretagogues, we used isolated colonic crypts in which changes in fluid transport can be temporally monitored while providing access to both luminal and basolateral receptors. In the absence of hormones, secretagogues, or bacterial toxins, net fluid transport was absorptive at an extracellular Ca2+ concentration of 0.1 mM (netJV in the first bars in Fig. 1a–d). This concentration of Ca2+ is sufficient to maintain epithelial integrity without activating the CaSR (EC50 = 0.75 mM; ref. 9). Exposure to cAMP-generating (forskolin or CTX; Fig. 1 e and f) or cGMP-generating (guanylin or STa; Fig. 1 g and h) factors increased cyclic nucleotide accumulation in colonocytes severalfold (Fig. 1 e–h) and shifted netJV from absorptive to secretory (second bars in Fig. 1 a–d). Even in the continued presence of each secretagogue, raising extracellular Ca2+ in the basolateral bath from 0.1 to 2 mM abrogated the net secretory responses to these agents (Fig. 1 a–d). The extracellular Ca2+-mediated reversal of the secretory response to each secretagogue was associated with a reduction in the corresponding cyclic nucleotide accumulation (Fig. 1 e–h).

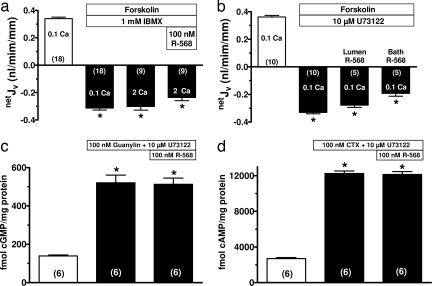

Fig. 1.

Increasing extracellular Ca2+ abrogates secretagogue-stimulated netJV and cyclic nucleotide accumulation. (a–d) Effects of raising basolateral bath Ca2+ on net fluid transport (netJV) in rat perfused crypts after cAMP (forskolin or cholera toxin, CTX) or cGMP (guanylin or STa endotoxin) generating secretagogues. Positive and negative values for netJV represent net absorption and secretion, respectively. (e–h) Secretagogue-stimulated increases in cyclic nucleotides are abrogated by raising extracellular Ca2+ to 2 mM, and this effect was absent after exposure to the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. Values in are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.01 compared with 0.1 mM Ca2+ without secretagogue; #, P < 0.01 compared with 0.1 mM Ca2+ plus secretagogue. The number in parentheses is the number of crypts (a–d) or tissues (e–h) studied. Calcium (Ca) concentrations are in millimolar.

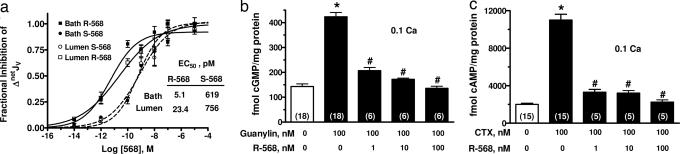

Because increasing extracellular Ca2+ can have effects on cells independent of an activation of the CaSR, we determined whether the R/S enantiomers of 568 (21), a specific small molecule receptor agonist, also modulated secretagogue-induced netJV and cyclic nucleotide accumulation. Calcimimetic compounds like R/S568 are small phenylalkylamine derivatives that bind to the CaSR and increase the affinity of the receptor for Ca2+ (i.e., function as allosteric modulators of the CaSR). Either luminal or basolateral application of R- or S-568 reversed the net fluid secretion induced by forskolin (Fig. 2a) with pM EC50 values. However, the R enantiomer of 568 was 30- to 100-fold more potent than the S enantiomer in reducing colonic fluid secretion, a stereospecific characteristic of the action of this compound on the CaSR (22). Similar to 2 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 1 e–h), R-568 dose-dependently reduced cGMP and cAMP accumulations induced by guanylin and CTX, respectively (Fig. 2 b and c).

Fig. 2.

The CaSR allosteric agonist, R-568, abrogates secretagogue-stimulated fluid secretion and cyclic nucleotide accumulation in rat colonic crypts. (a) Concentration dependence of R and S enantiomers of 568 in lumen or bath perfusate on 10 μM forskolin-stimulated net fluid secretion (netJV) in rat perfused colonic crypts. (b and c) R-568 dose-dependently reduced cyclic nucleotide accumulation stimulated by 500 μM guanylin or 100 nM cholera toxin, respectively. Values are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.01 compared with no secretagogue; #, P < 0.01 compared with secretagogue without CaSR agonist. The number in parentheses is the number of crypts (a) or tissues (b and c) studied. Calcium (Ca) concentrations are in millimolar.

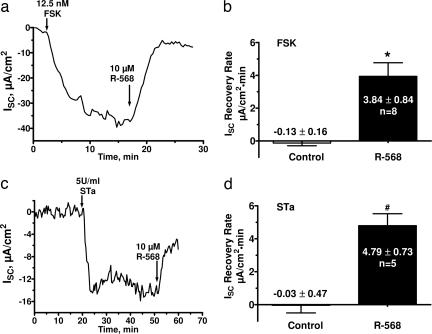

We also assessed the effects of Vmax concentrations of R-568 on forskolin and STa-stimulated short circuit current, ISC, in distal colon. Addition of 10 μM R-568 to the serosal bath rapidly modulated secretagogue-stimulated ISC (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

R-568 reverses the short circuit current, ISC, induced by forskolin (FSK) or STa. Rat distal colonic strips (0.3 cm2) with the muscle layer removed were mounted in an Ussing chamber in symmetrical Hepes-buffered ringers at 37°C and gassed with 100% O2. (a and c) Representative current traces showing the change in ISC induced by serosal bath additions of 12.5 nM FSK (a) or 5 units/ml STa (c) and the reversal of secretagogue-induced ISC by serosal 10 μM R-568. (b and d) Summary of the rate of reduction in negative ISC induced by 10 μM R-568. Control rates were obtained from the steady state ISC values 2–5 min before adding R-568. Data are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.005 vs. control; #, P < 0.02 vs. control.

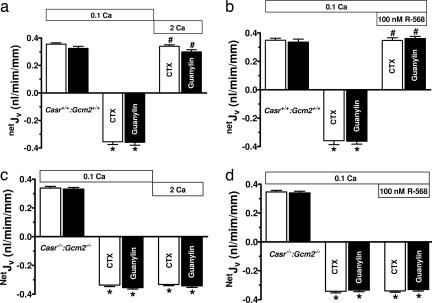

Effects of Ca2+ and R-568 on Fluid Transport Are Absent in CaSR-Null Mice.

Deletion of the Casr gene results in early postnatal mortality from the toxic effects of unregulated release of parathyroid hormone (PTH) from parathyroid chief cells as well as from the pathological effects of the consequent hypercalcemia (23). Glial cells missing 2 (Gcm2) is a regulatory gene critical for parathyroid gland development, and deletion of Gcm2 results in mice having no parathyroid glands (24). However, these Gcm2−/− mice exhibit a low circulating level of PTH, probably emanating from the thymus sufficient to maintain skeletal integrity, and this source of PTH is not regulated by the CaSR (24, 25). Thus, deletion of Gcm2 eliminates the early mortality in Casr-null mice (25). Therefore, we used these double knockout, Casr−/−::Gcm2−/−, mice to assess the effects of extracellular Ca2+ or R-568 on secretagogue-stimulated net fluid secretion in colonic crypts. Colonic crypts from wild-type Casr+/+::Gcm2+/+ mice exhibited similar rates of basal net fluid absorption and secretory responses to CTX and guanylin (Fig. 4) as observed in rats. Whereas either 2 mM Ca2+ or 100 nM R-568 abolished the fluid secretory responses to these toxins in Casr+/+::Gcm2+/+ mice (Fig. 4 a and b), the effects of these receptor agonists on toxin-stimulated net fluid secretion were completely absent in Casr−/−::Gcm2−/− mice (Fig. 4 c and d).

Fig. 4.

Absence of effects of 2 mM Ca2+ or R-568 on secretagogue-stimulated net fluid secretion in CaSR null mice. (a and b) Increasing bath Ca2+ to 2 mM (a) or bath addition of 100 nM R-568 (b) reversed the net fluid secretion induced by 100 nM CTX (open bars; n = 8) or 500 μM guanylin (filled bars; n = 9) in perfused colonic crypts from wild-type mice, Casr+/+::Gcm2+/+. (c and d) The ability of bath 2 mM Ca2+ or bath 100 nM R-568 failed to reverse fluid secretion induced by secretagogues (n = 18) in the CaSR receptor knockout mouse, Casr−/−:Gcm2−/−. Values are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.001 compared with no secretagogue; #, P < 0.01 compared with secretagogue without CaSR agonist. Calcium (Ca) concentrations are in millimolar.

Effects of the CaSR Mediated by Ca2+-Dependent Phosphodiesterases.

CaSR-mediated reductions in cyclic nucleotide accumulations in colonocytes could be due to reduced production by cyclases and/or increased degradation by phosphodiesterases (PDEs). The CaSR can activate pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibitory G proteins (26) in certain cells [e.g., Gαi2 in parathyroid gland cells (2) and epithelial cells in the kidney (13)], which decreases adenylyl cyclase activity, and consequently, cAMP accumulation. However, CTX functions as an irreversible direct activator of adenylyl cyclase, which should be unaffected by Gαi interactions. In addition, inhibitory Gαi proteins would not be expected to alter guanylyl cyclase C-type guanylin receptor activated by STa. These observations suggested that the CaSR-mediated reductions in toxin-stimulated cyclic nucleotide accumulation (Fig. 1 e–h) and netJV (Fig. 1 a–d) may have resulted from increased cyclic nucleotide degradation, rather than reduced generation of these nucleotides. In support of a role for CaSR-mediated enhanced cyclic nucleotide degradation in colonic crypts, the isoform-nonspecific PDE inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) abolished the ability of 2 mM Ca2+ to reduce secretagogue-induced increases in cyclic nucleotide accumulation (Fig. 1 e–h). In addition, IBMX abolished the ability of 2 mM Ca2+ to reverse forskolin-stimulated fluid secretion even in the presence of 100 nM R-568 (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

IBMX and PLC inhibition abrogates the effects of R-568 on netJV and cyclic nucleotide accumulation in rat colonic crypts. (a) IBMX abolished the effects of 2 mM Ca2+ and/or 100 nM R-568 to reverse the effect of 10 μM forskolin on netJV. (b) The phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122 abolishes the ability of lumen or bath R-568 to reverse forskolin-stimulated fluid secretion. PLC inhibition blocked the ability of 100 nM R-568 to reverse cGMP or cAMP accumulation in colonic crypt cells induced by guanylin (c) or cholera toxin (CTX; d), respectively. Values are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.001 compared with no secretagogue. The number in parentheses is the number of crypts (a and b) or tissues (c and d) studied. Calcium (Ca) concentrations are in millimolar.

Stimulation of the CaSR in virtually all cells increases cytosolic Ca2+ via activation of PLC by Gαq. Because the PLC inhibitor U73122 abolishes the ability of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ to increase intracellular calcium in rat crypts (10), we used this inhibitor to examine whether a receptor-mediated rise in cytosolic Ca2+ was critical for the action of lumen or bath R-568 on forskolin-stimulated fluid secretion. Fig. 5b shows that PLC inhibition with U73122 had no effect on the ability of forskolin to induce a fluid secretory response, but significantly reduced the effect of lumen or bath R-568 to reverse fluid secretion. Because a fall in cyclic nucleotide accumulation accompanies the CaSR-mediated modulation of fluid secretion (Figs. 1 and 5a), the effect of U73122 on netJV suggested that a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ may be required to activate colonic PDEs. To examine this possibility, we assessed the effects of U73122 on the ability of R-568 to reduce cyclic nucleotide accumulations with guanylin and CTX. In the presence of this PLC inhibitor, R-568 no longer reduced cyclic nucleotide accumulations (Fig. 5 c and d compared with Fig. 2 b and c), supporting the need for an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in the activation of IBMX-sensitive PDE by the CaSR in colonocytes.

CaSR Mediates Inhibition of Basolateral NCKK1 Activity.

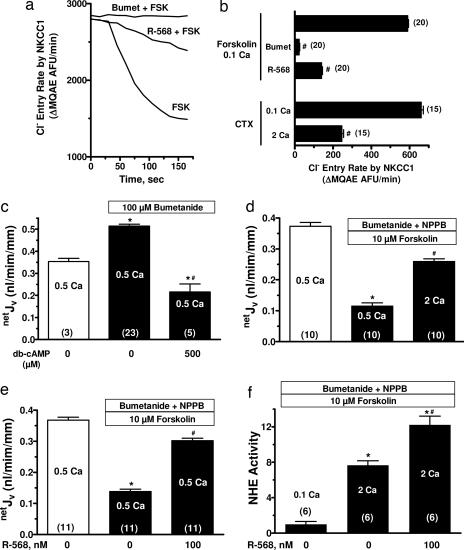

Fluid secretion into the lumen of colonic crypts depends on movement of chloride ions (Cl−) across the luminal plasma membrane through the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels (CFTR) (27), and mice deficient in CFTR lack a secretory response to CTX (28). Secretagogue-induced increases in cellular accumulation of cAMP or cGMP enhances PKA and PKG (19, 27) phosphorylation processes, respectively, which drives translocation of activated CFTR channels to the luminal plasma membrane. Equally critical for transepithelial Cl− transport during secretagogue-stimulated fluid secretion is increased Cl− entry into cells from the basolateral fluid via the bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC1; ref. 27). Adult mice lacking NKCC1 exhibit impaired secretory responses to cAMP and STa (29). In rat perfused colonic crypts, basolateral addition of 10−4 M bumetanide abolished forskolin-stimulated basolateral Cl− entry into colonic crypt cells (Fig. 6a and b). Addition of 100 nM R-568 to the basolateral fluid also significantly reduced the rate of forskolin-stimulated Cl− entry (Fig. 6 a and b). A similar inhibition of Cl− entry via NKCC1 was seen in the presence of CTX with increasing Ca2+ from 0.1 to 2 mM (Fig. 6b). Thus activation of the CaSR inhibits NKCC1 activity, a critical component of the fluid secretory mechanism.

Fig. 6.

Extracellular Ca2+ or R-568 reverses secretagogue-induced inhibition of fluid absorption in rat colonic crypts. (a and b) Cl− entry into rat crypt cells, monitored by the rate of decrease in MQAE fluorescence, is increased by 10 μM forskolin (FSK) and 100 nM CTX, and this increase was inhibited by bumetanide, 2 mM Ca2+, or 100 nM R-568. (c) Bumetanide increased absorptive netJV in the absence of secretagogues, and this absorptive flux was reduced after addition of dibutyryl-cAMP (db-cAMP). (d and e) 2 mM Ca2+ or R-568 reversed forskolin-inhibited net fluid absorption in the presence of bath bumetanide and a luminal Cl− channel inhibitor (100 μM NPPB). (f) Forskolin inhibited Na+-H+ exchanger (NHE3) activity was reversed by 2 mM Ca2+ or R-568. Cell acid loading was accomplished by exposure to NH4Cl, and Na+-dependent cell pH recovery after removal of NH4Cl was assessed as an index of Na+/H+ activity (51).Values are mean ± SEM; ∗, P < 0.01 compared with no secretagogue; #, P < 0.01 compared with secretagogue without inhibitor or CaSR agonist. The number in parentheses is the number of crypts studied. Calcium (Ca) concentrations are in millimolar.

CaSR Enhances Fluid Absorption.

Secretory diarrheas result not only from enhanced fluid secretion, but also from reduced fluid absorption (27, 30). A major component of fluid absorption in the colon (and small intestine) is mediated by parallel Na+/H+ (sodium–hydrogen exchanger, NHE) and Cl−/HCO3− exchange located at the apical plasma membranes (27, 30). Cyclic nucleotides reduce this Na+-dependent fluid absorption by inhibiting NHE activity (31). In the absence of secretagogues, addition of bumetanide to the basolateral bath of perfused crypts slightly increased the positive or absorptive netJV due to inhibition of a small remaining fluid secretion (Fig. 6c). This basal fluid secretion was likely due to the low levels of cell cyclic nucleotides that remain even in the absence of secretagogues (Fig. 1 e–h). Thus, in the presence of bumetanide, netJV measurements represent the absorptive component of fluid transport. This absorptive fluid movement was substantially reduced by addition of cAMP (Fig. 6c) or forskolin (Fig. 6d), which would importantly contribute to secretagogue-induced diarrheas. Either increasing extracellular Ca2+ to 2 mM (Fig. 6d) and/or addition of R-568 (Fig. 6e) to the basolateral bath significantly abrogated the cAMP-mediated reduction in fluid absorption. To examine whether this latter effect of CaSR agonists resulted from modulation of NHE activity, we assessed the effects of Ca2+ or R-568 on Na+-dependent proton extrusion from colonocytes in the presence of forskolin. NHE activity was increased 8-fold by raising basolateral bath Ca2+ from 0.1 to 2 mM, and addition of R-568 to the 2 mM Ca2+-containing bath resulted in a further increase in NHE activity (Fig. 6f).

Discussion

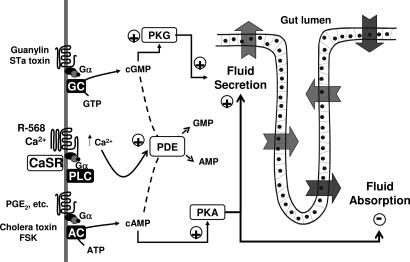

Neurogenic and local hormonal factors regulate the production of cyclic nucleotides in intestinal epithelial cells to promote net fluid secretion during normal digestion. This physiological regulation of intestinal secretion occurs by distinct ion transport processes (27, 32) that increase the secretory component and reduce the absorptive component (27) of transepithelial fluid movement. A model for the effects of CaSR activation on fluid transport by colonic crypts is shown in Fig. 7. Our study in colonic crypts shows that CaSR activation abrogated net fluid secretion and cyclic nucleotide accumulation induced by synthetic/natural secretagogues like forskolin (33) and guanylin (34), which generate cAMP and cGMP, respectively. Intestinal enterocytes express a functional CaSR on both luminal or basolateral membranes of these polarized cells (10), and CaSR agonists have been shown to be similarly effective from the perfusate and bath in perfused colonic crypts. Accordingly, local solute signals from both the gut luminal and tissue compartments can activate the CaSR to function as a negative modulator of physiological neurogenic and local hormonal secretory actions and provide a mechanism for fine tuning of net fluid movement during normal digestion. Enteric bacterial pathogens elaborate factors like cholera (35) and STa (36) toxins that exploit this cyclic nucleotide cell signaling system to cause severe diarrhea (37). CaSR agonists modulate cyclic nucleotide accumulation even in the presence of these toxigenic secretagogues showing that CaSR action in colonic crypts is independent of the mechanism of cAMP or cGMP generation. Both increased fluid secretion and reduced fluid absorption contribute to the profound fluid losses in toxigenic diarrheas (27, 38), and both components of intestinal fluid movement were reversed by increasing extracellular Ca2+ or addition of the small-molecule receptor agonist or calcimimetic, R-568. This negative regulatory action of the CaSR on intestinal fluid secretion would contribute to the constipating effect of increasing oral calcium intake and the ameliorating effect of oral calcium on the severity of diarrhea resulting from entertoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in humans (39).

Fig. 7.

Model for CaSR-mediated abrogation of secretagogue effects on fluid transport by colonic crypts. cAMP and cGMP are generated by activation of receptors coupled to adenylyl cyclase (AC) and guanylyl cyclase (GC), respectively. Stimulation of either receptor pathway [guanylin or STa toxin for cGMP; cholera toxin or forskolin (FSK) for cAMP] enhances fluid secretion and reduces fluid absorption. Activation of the CaSR by Ca2+ or R-568 stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) activity that generates IP3, resulting in the release of Ca2+ from thapsigargin-sensitive stores. Ca2+-dependent activation of phosphodiesterases (PDE) in crypt cells metabolizes cyclic nucleotides and reverses the effect of secretagogues on fluid transport.

Several observations support our conclusion that the parallel reductions in secretagogue-stimulated cyclic nucleotide accumulation and net fluid secretion depend on CaSR activation. First, increases in extracellular Ca2+ or addition of R-568 were ineffective in modulating the actions of secretagogues in CaSR-null mice. Second, both the pM affinity of R-568 and the 2- to 3-log difference in affinities for the R and S enantiomers of this compound support a specific action of this calcimimetic on the intestinal CaSR (22). Finally, the agonist-mediated modulations of secretagogue effects in rat colonocytes could be abolished by inhibition of PLC, a lipase universally activated by the CaSR via Gαq (2, 7).

At least three mechanisms account for effects of CaSR on net fluid transport in colonic crypts. First, CaSR agonists enhanced cyclic nucleotide destruction via activation of PDEs. Consistent with this notion, we showed that the effects of CaSR agonists on net fluid secretion correlated with reductions in cyclic nucleotide accumulations and that the isoform-nonspecific PDE inhibitor IBMX abolished the effects of Ca2+ or R-568 on toxigenic fluid secretion and cyclic nucleotide accumulations. There are 11 families of cyclic nucleotide PDEs, each exhibiting specific affinities for degrading cAMP and/or cGMP (40, 41). Although little information is available on the specific PDE genes expressed in intestinal epithelial cells, PDE1–5 isoforms have been identified in human colon cancer cells (42, 43) and each of these PDEs is sensitive to IBMX. Because inhibition of PLC signaling abolishes CaSR effects on cAMP and cGMP accumulation, activation of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent PDE1 family members (40) appear to be involved in receptor-mediated increases in cyclic nucleotide destruction.

A second mechanism contributing to the CaSR-induced abrogation of net fluid secretion is inhibition of basolateral Na-K-2Cl (NKCC1) activity, which mediates Cl− entry into crypt cells required for sustained chloride and fluid secretion. Although increases in cAMP-dependent PKA activity are associated with phosphorylation, and thereby stimulation, of NKCC1 in secretory epithelia, the mechanism is believed to be indirect (38, 44). The increase apical insertion of activated CFTR by cAMP-PKA enhances cell Cl− exit and lowers cytosolic Cl− activity. The latter stimulates the phosphorylation-activation of NKCC1 by the STE-20 kinase, SPAK (45, 46). Because CaSR agonists reduce cyclic nucleotide accumulation, diminution in CFTR activity would increase cell Cl− and inhibit NKCC1. However, the results in Fig. 6 a and b were obtained under reduced cell Cl− conditions, suggesting that CaSR agonists also inhibit NKCC1 by an alternative mechanism. CaSR agonists generate a myriad of 2nd messenger signals in different cells via activation of PLC, cPLA2, and PLD (2, 7) and the array of downstream effector pathways have yet to be fully elucidated. Although our results do not define the specific cell signaling pathway mediating the inhibition of NKCC1 by CaSR agonists, a reduction in cotransporter function would contribute to reducing intestinal fluid secretion.

A third mechanism contributing to the CaSR-induced abrogation of net fluid secretion in colonic crypts is activation of fluid absorption. Elevations in cAMP and cGMP inhibit intestinal NaCl absorption in ileum and colon by reducing NHE activity (47), and this event contributes importantly to severity of fluid and electrolyte losses in secretory diarrheas (27, 38). Our studies demonstrate that activation of the CaSR reverses the cyclic nucleotide-mediated reductions in the absorptive components of net fluid transport. Activation of apical NHE is responsible for a major component of intestinal fluid absorption and both the rise in cell calcium and the reduction in cAMP associated with CaSR activation would provide mechanisms for increasing apical NHE activity in intestinal epithelia.

In conclusion, the colonic luminal- and interstitial-side CaSRs function as negative modulator of the action of cAMP- or cGMPgenerating secretagogues on intestinal fluid transport by stimulating the degradation of these cyclic nucleotides by phosphodiesterases. We propose that small-molecule CaSR agonists (i.e., calcimimetics) may provide a therapy for secretory diarrheas resulting from bacterial toxins, neuronal or hormonal secretagogues, or other cyclic-nucleotide generating mechanisms. Although the CaSR is expressed in many tissues and cell types in mammals, intestinal luminal-side receptor activation by nonabsorbable calcimimetics would provide one means for achieving potent antidiarrheal effects that would avoid systemic CaSR activation.

Materials and Methods

Colonic Crypt Isolation.

Overnight fasted male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–250 g) and Casr+/+::Gcm2+/+ or Casr−/−::Gcm2−/− mice were euthanized and colonic crypts isolated as described (10) and in accordance with the humane practices of animal care established by the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee. To obtain isolated crypts for perfusion or measurement of cell pH, colonic segments were hand dissected. For measurement of cyclic nucleotide accumulations or determination of crypt cell chloride, colonic segments were everted and incubated for 15 min at 37°C in Na-EDTA buffer containing 96 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM KCl, 21 mM Na EDTA, 55 mM sorbitol, 22 mM sucrose, and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 followed by vigorous agitation for 30 s to release individual crypts. Crypts were collected by centrifugation (2,000 rpm for 5 min in Beckman Coulter Allegra 6R Centrifuge), washed three times in basal Ringer's solution in which Ca2+ and Mg2+ were reduced to 0.1–0.5 mM, and then resuspended in basal Ringer's solution. Released crypts were immediately mixed with 2 volumes of standard Ringers solution containing 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO2, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM d-glucose, and 32 mM Hepes, pH 7.4.

Crypt Perfusion and JV Measurement.

Single, hand-dissected crypts were placed in a temperature-controlled chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope and perfused in vitro as described (20). Briefly, crypts were perfused (4–10 nl/min) with a solution containing exhaustively dialyzed methoxy-[3H]inulin (10 μCi/ml; PerkinElmer; 1 Ci = 37 GBq). The effluent was sampled with a volume-calibrated pipette. netJV (nl/min per mm of crypt length) was determined from the length and diameter of the crypt, the rate at which the effluent accumulates in the collection pipette and from the activity of methoxy-[3H]inulin in the perfusate and effluent. Bath was also collected for each experiment; experiments were discarded whenever bath [methoxy-[3H]inulin] exceeded background. Each data point consisted of the average of three 5-min collections of effluent. At least five crypts from at least three animals were studied in each experimental protocol. Crypt viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. All secretagogues were added to the bath perfusate. CaSR agonists were added to the luminal, bath, or both perfusates as indicated.

cAMP and cGMP Measurements.

Colonic crypt suspensions were incubated at 37°C with forskolin for 15 min, cholera toxin for 90 min, or guanylin or STa for 45 min in the presence or absence of 1 mM IBMX. Crypts were exposed to a Hepes buffer containing either 0.1 or 2 mM Ca2+ where indicated. Reactions were terminated by addition of 2 ml of ice-cold pure (100%) ethanol to 1 ml of crypt cell suspensions, resulting in a final suspension volume of 66% (vol/vol) ethanol. The resulting precipitate was washed one time with ice-cold 66% (vol/vol) ethanol. The extracts were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm (201 × g) for 15 min at 4°C and then lyophilized under 65°C vacuum. cAMP and cGMP (femtomoles per mg of protein) were measured by enzyme immunoassay (cAMP Biotrak Enzymeimmunoassay System, Amersham Pharmacia).

Cl− Measurements.

Cell Cl− influx measurements (48) were performed on isolated superfused colonic crypts on glass coverslips coated with Cell-Tak (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) and loaded with 20 mM MQAE [(N-6-methoxyquinolyl) acetoethyl ester; Molecular Probes]. After dye loading, crypts were incubated in a Cl−-free Hepes buffer until stable high baseline fluorescence intensity was achieved. Rates of cell Cl− influx were monitored as rates of reductions in arbitrary MQAE fluorescent units (ΔAFU/min; Ex, 346 nm; Em, 460 nm).

Intracellular pH Measurements.

Intracellular pH measurements (49) were used to assess Na+-dependent, amiloride-sensitive Na+/H+ exchanger activity in apical membranes of isolated perfused colonic crypts loaded with 5 μM BCECF-AM (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence intensity ratio data (490 nm/440 nm) were converted to pH values by using the nigericin calibration technique (49).

Short Circuit Current.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 150–300 g were euthanized, and muscle-stripped segments of distal colon isolated as described (50) and in accordance with the humane practices of animal care established by the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee. Segments of 0.3 cm2 surface area were mounted in modified Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA), bathed in Hepes-buffered saline solution containing 110 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, and 22 mM Hepes (pH 7.4 when gassed with 100% O2 at 37°C). Short circuit current, ISC (μA/cm2), was monitored and recorded by computer every 10–20 s. Rates of change in ISC (μA/cm2 · min) were determined before and after additions of R-568 or vehicle and significance tested by using the paired Student's t test.

Chemicals.

Forskolin, cholera toxin, guanylin, STa, IBMX, and bumetanide were obtained from Sigma, and stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). NPPB [5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid] was obtained from Calbiochem. Final concentrations of DMSO never exceeded 0.1% (vol/vol). R-568 and S-568 were from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA).

Statistical Analysis.

One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's multiple comparison tests were used for paired or unpaired data comparisons.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. D. Quarles (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City) for the kind gift of the Casr−/−::Gcm2−/− double knockout mice23 and a Casr+/−::Gcm2+/− breeder pair used in these studies, and Lieqi Tang and Qingshang Yan for mouse genotyping. S.C.H. and J.G. thank Amgen for research support. This work was supported in part by a gift from Amgen.

Abbreviations

- CaSR

calcium-sensing receptor

- CTX

cholera toxin

- STa

E. coli heat stable enterotoxin

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- PDE

phosphodiesterases

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- NHE

sodium–hydrogen exchanger.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: S.C.H. is an inventor on patents covering CaSR active molecules, receives royalties on calcimimetics, and is a consultant on calcimimetics at Amgen, Inc. This work was supported in part by a gift from Amgen.

See accompanying Profile on page 9387.

References

- 1.Abbott G. W. S. Cell. 1999;97:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown E. M., MacLeod R. J. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:239–297. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nearing J., Betka M., Quinn S., Hentschel H., Elger M., Baum M., Bai M., Chattopadyhay N., Brown E. M., Hebert S. C., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9231–9236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152294399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown E. M., Gamba G., Riccardi D., Lombardi M., Butters R., Kifor O., Sun A., Hediger M. A., Lytton J., Hebert S. C. Nature. 1993;366:575–580. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riccardi D., Park J., Lee W. S., Gamba G., Brown E. M., Hebert S. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:131–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sands J. M., Naruse M., Baum M., Jo I., Hebert S. C., Brown E. M., Harris H. W. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1399–1405. doi: 10.1172/JCI119299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tfelt-Hansen J., Brown E. M. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2005;42:35–70. doi: 10.1080/10408360590886606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chattopadhyay N., Cheng I., Rogers K., Riccardi D., Hall A. E., Diaz R., Hebert S. C., Soybel D. I., Brown E. M. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:G122–G130. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng S. X., Geibel J. P., Hebert S. C. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:148–158. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S. X., Akuda M., Hall A. E., Geibel J. P., Hebert S. C. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;283:G240–G250. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert S. C., Cheng S. X., Geibel J. P. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheinin Y., Kallay E., Wrba F., Kriwanek S., Peterlik M., Cross H. S. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2000;48:595–602. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jesus Ferreira M. C., Helies-Toussaint C., Imbert-Teboul M., Bailly C., Verbavatz J. M., Bellanger A. C., Chabardes D. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15192–15202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raufman J. P. Am. J. Med. 1998;104:386–394. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qadri F., Svennerholm A. M., Faruque A. S., Sack R. B. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:465–483. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.465-483.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banwell J. G., Pierce N. F., Mitra R. C., Brigham K. L., Caranasos G. J., Keimowitz R. I., Fedson D. S., Thomas J., Gorbach S. L., Sack R. B., et al. J. Clin. Invest. 1970;49:183–195. doi: 10.1172/JCI106217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaandrager A. B. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2002;230:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas M. L. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;90:7–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golin-Bisello F., Bradbury N., Ameen N. Am. J. Physiol. 2005;289:C708–C716. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00544.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh S. K., Binder H. J., Boron W. F., Geibel J. P. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:2373–2379. doi: 10.1172/JCI118294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemeth E. F., Steffey M. E., Hammerland L. G., Hung B. C., Van Wagenen B. C., DelMar E. G., Balandrin M. F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammerland L. G., Garrett J. E., Hung B. C., Levinthal C., Nemeth E. F. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho C., Conner D. A., Pollak M. R., Ladd D. J., Kifor O., Warren H. B., Brown E. M., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:389–394. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunther T., Chen Z. F., Kim J., Priemel M., Rueger J. M., Amling M., Moseley J. M., Martin T. J., Anderson D. J., Karsenty G. Nature. 2000;406:199–203. doi: 10.1038/35018111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu Q., Pi M., Karsenty G., Simpson L., Liu S., Quarles L. D. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1029–1037. doi: 10.1172/JCI17054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neves S. R., Ram P. T., Iyengar R. Science. 2002;296:1636–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.1071550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunzelmann K., Mall M. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:245–289. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabriel S. E., Brigman K. N., Koller B. H., Boucher R. C., Stutts M. J. Science. 1994;266:107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.7524148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flagella M., Clarke L. L., Miller M. L., Erway L. C., Giannella R. A., Andringa A., Gawenis L. R., Kramer J., Duffy J. J., Doetschman T., et al. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26946–26955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donowitz M., Welsh M. J. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1986;48:135–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yun C. H. C., Oh S., Zizak M., Steplock D., Tsao S., Tse C.-M., Weinman E. J., Donowitz M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3010–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett K. E., Keely S. J. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:535–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seamon K. B., Daly J. W. J. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1981;7:201–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currie M. G., Fok K. F., Kato J., Moore R. J., Hamra F. K., Duffin K. L., Smith C. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:947–951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores J., Sharp G. W. Ciba Found. Symp. 1976:89–108. doi: 10.1002/9780470720240.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Field M., Graf L. H., Jr, Laird W. J., Smith P. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uzzau S., Fasano A. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:83–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Field M. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI18326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bovee-Oudenhoven I. M., Lettink-Wissink M. L., Van D. W., Witteman B. J., van der M. R. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beavo J. A. Physiol. Rev. 1995;75:725–748. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon Y. H., Heo Y. S., Kim C. M., Hyun Y. L., Lee T. G., Ro S., Cho J. M. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1198–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4533-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soh J. W., Mao Y., Kim M. G., Pamukcu R., Li H., Piazza G. A., Thompson W. J., Weinstein I. B. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:4136–4141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Grady S. M., Jiang X., Maniak P. J., Birmachu W., Scribner L. R., Bulbulian B., Gullikson G. W. J. Membr. Biol. 2002;185:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haas M., Forbush B., III Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:515–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowd B. F., Forbush B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:27347–27353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piechotta K., Garbarini N., England R., Delpire E. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52848–52856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zachos N. C., Tse M., Donowitz M. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:411–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.153004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egan M. E., Glockner-Pagel J., Ambrose C., Cahill P. A., Pappoe L., Balamuth N., Cho E., Canny S., Wagner C. A., Geibel J., et al. Nat. Med. 2002;8:485–492. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binder H. J., Singh S. K., Geibel J. P., Rajendran V. M. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1997;118:A265–A269. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Binder H. J., Rawlins C. L. Am. J. Physiol. 1973;225:1232–1239. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.5.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh S. K., Binder H. J., Geibel J. P., Boron W. F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11573–11577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]