Abstract

A process for preparation of amides from unactivated esters and amines has been developed using a catalytic system comprised of group (IV) metal alkoxides in conjunction with additives including 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt). In general, ester–amide exchange proceeds using a variety of structurally diverse esters and amines without azeotropic reflux to remove the alcohol byproduct. Initial mechanistic studies on the Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt system revealed that the active catalyst is a novel, dimeric zirconium complex as determined by X-ray crystallography.

Introduction

The carboxamide is an important functional group which exists in numerous natural products and synthetic molecules. Although direct transformation of esters to amides is a potentially valuable process for synthesis of complex molecules, stoichiometric amounts of promoters or metal mediators1 are typically required. Limited examples have been reported involving catalytic ester–amide exchange. In this regard, Yamamoto and co-workers have reported the intramolecular, metal-templated macrolactamization of tetra-amino esters using stoichio-metric amounts of Sb(OEt)3 as well as several catalytic, intermolecular examples involving azeotropic removal of methanol.2 During the course of a total synthesis effort, we considered development of a catalytic method for intramolecular ester–amide exchange to prepare macrolactams. Herein, we report our initial studies regarding development of an ester–amide exchange process catalyzed by zirconium (IV) tert-butoxide in conjunction with activators including 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt) as well as initial studies to probe the reaction mechanism.

Results and Discussion

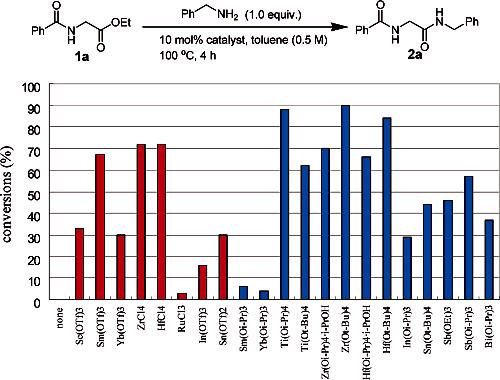

Catalyst Screening. On the basis of literature precedent for the catalytic condensation of carboxylic acids with amines3 and alcohols,4 transesterification,5 ester–amide exchange,2 and transamidation,6 we first evaluated two classes of metal catalysts: Lewis acidic metal triflates/halides and bifunctional metal alkoxides. The catalytic efficiency of metal complexes was first evaluated for condensation of the model amino ester 1a and benzylamine in toluene at 100 °C (Figure 1). A control experiment showed no conversion and established the requirement for the metal catalyst to afford amide 2a. In general, group (IV) metal catalysts were found to be superior, and Ti(Oi-Pr)4, Zr(Ot-Bu)4, and Hf(Ot-Bu)4 afforded optimal conversions.

Figure 1.

Results of catalyst screening for ester–amide exchange using benzylamine and ethyl hippurate. Conversion based on 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

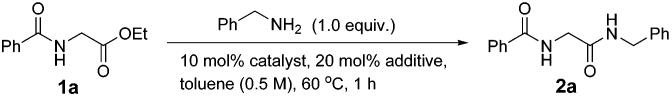

Evaluation of Additive and Solvent Effects. To further improve the catalytic ester–amide exchange process, we anticipated that addition of catalytic amounts of activators as additives7 may lead to higher reaction efficiency. For example, use of DMAP has been reported to enhance the reactivity in Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed acylation of tertiary alcohols.8 Activators including HOBt,9 HOAt,10 PFP,11 and HYP12 are widely used in standard amide coupling for both rate acceleration and suppression of racemization. Our initial supposition was that such activators may cooperate with the metal alkoxides to produce activated ester intermediates in situ.13 A variety of activators were thus evaluated in combination with group (IV) metal alkoxides (Table 1); none showed noticeable improvement for Ti(Oi-Pr)4. However, except for DMAP, O-based activators significantly enhanced the reaction efficiency for both Zr(Ot-Bu)4 and Hf(Ot-Bu)4 in which the combination of Zr(Ot-Bu)4 and HOAt showed optimal conversions.14 Other metal–oxybenzotriazolates15 including Cu(OBt)2,16 previously used to minimize racemization in peptide coupling, were found to be less effective.17

Table 1.

|

| none | HOBt | HOAt | PFP | HYP | DMAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti(Oi-Pr)4 | 30 | 24 | 17 | 11 | 30 | 34 |

| Zr(Ot-Bu)4 | 33 | 79 | 90 | 81 | 85 | 24 |

| Hf(Ot-Bu)4 | 38 | 80 | 84 | 77 | 75 | 35 |

Reaction conditions: ethyl hippurate (0.50 mmol), benzylamine (0.50 mmol), catalyst (0.05 mmol), additive (0.10 mmol), toluene (1 mL), 60 °C, 1 h. Percent conversion based on 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

HOBt = 1-hydroxybenzotriazole, HOAt = 1-hydroxy-7-azaben-zotriazole, PFP = pentafluorophenol, HYP = 2-hydroxypyridine, DMAP = 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine.

Further examination of the ratio of catalyst and activator indicated that a 1:1 ratio of Zr(Ot-Bu)4 and HOAt afforded optimal conversion using toluene as solvent (Table 2, entry 2). After solvent screening, we found that the ester–amide exchange proceeded well in a number of aprotic solvents including benzene, DCE, THF, dioxane, and CH3CN.

Table 2.

Evaluation of Catalyst Composition and Reaction Solventa

| entry | Zr(Ot-Bu)4: HOAt | solvent | conditions | conversionb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2:1 | toluene | 60 °C, 1 h | 85 |

| 2 | 1:1 | toluene | 60 °C, 1 h | 96 |

| 3 | 1:2 | toluene | 60 °C, 1 h | 90 |

| 4 | 1:3 | toluene | 60 °C, 1 h | 85 |

| 5 | 1:4 | toluene | 60 °C, 1 h | 78 |

| 6 | 1:1 | toluene | rt, 12 h | 97c (92d) |

| 7 | 1:1 | benzene | rt, 12 h | 97c |

| 8 | 1:1 | DCE | rt, 12 h | 85c |

| 9 | 1:1 | THF | rt, 12 h | 95c |

| 10 | 1:1 | 1,4-dioxane | rt, 12 h | 80c |

| 11 | 1:1 | CH3CN | rt, 12 h | 85c |

Reaction conditions: ethyl hippurate (0.50 mmol), benzylamine (0.50 mmol), Zr(Ot-Bu)4 (0.05 mmol), HOAt and solvent (1 mL).

Conversion based on 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

1.1 equiv of benzylamine employed.

Isolated yield after purification by silica gel chromatography.

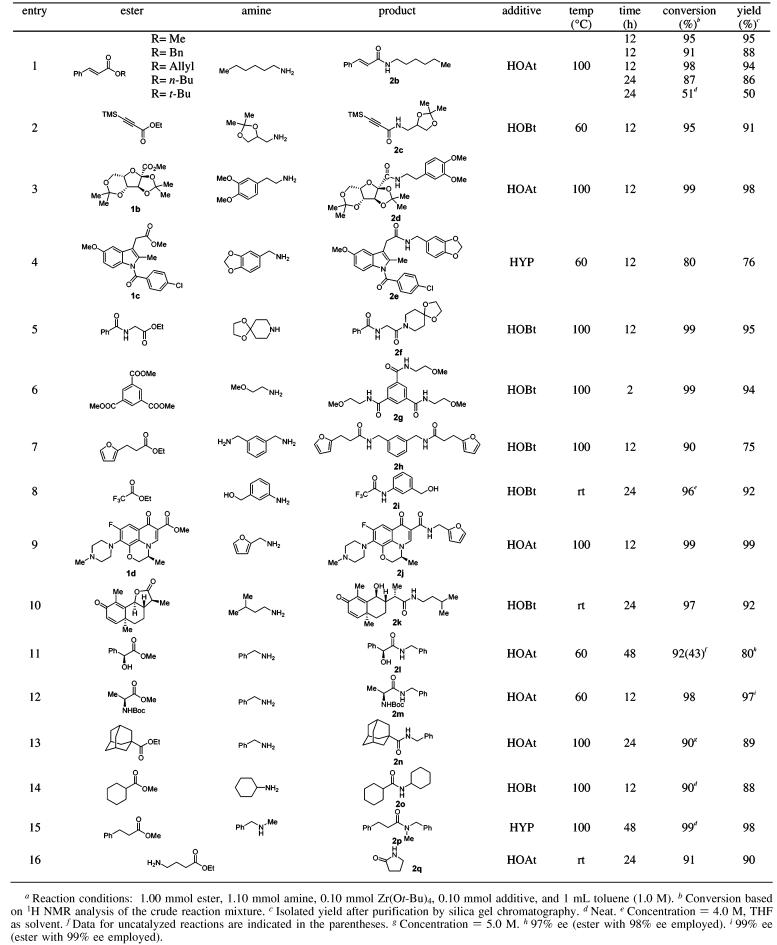

Scope and Limitations. The scope of the zirconium-catalyzed ester–amide exchange was examined by reaction of a number of structurally diverse esters and amines using 10 mol % Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt or HOBt (Table 3). HOBt was chosen as a suitable, less expensive alternative to HOAt. Our overriding interest was to determine the utility of ester–amide exchange using complex substrates. In all cases, reactions proceeded smoothly between both aliphatic and aromatic substrates without azeotropic removal of the corresponding alcohol byproducts, and control experiments indicated that the reactions did not proceed without catalyst.18 It should be noted that the ester scope is not limited to simple methyl or ethyl esters. With the exception of the sterically hindered tert-butyl ester, all cinnamic acid esters examined (methyl, benzyl, allyl, n-butyl) showed good reactivity (Table 3, entry 1). The reaction conditions were found to be slightly basic, since a number of acid-sensitive (acetals and ketals) and base-sensitive (trimethylsilyl) functional groups were unaffected (entries 2–5) except for the exceedingly base-sensitive Fmoc group. Another attractive feature of the transformation is its excellent chemoselectivity as illustrated in entries 8 (aromatic amine vs aliphatic alcohol), 9 and 10 (ester and lactone vs conjugate ketone). Little or no epimerization was observed for optically active, N-Boc protected α-amino and α-hydroxy esters under the reaction conditions (entries 11–12). High concentration was found to be beneficial for reactions involving less reactive or sterically hindered esters and amines (entries 13–15). We found that 2-hydroxypyridine was more effective than HOAt as additive in certain cases (cf. entries 4 and 15). An intramolecular lactam formation also proceeded smoothly at room temperature (entry 16).

Table 3.

Ester–Amide Exchange: Reaction Scopea

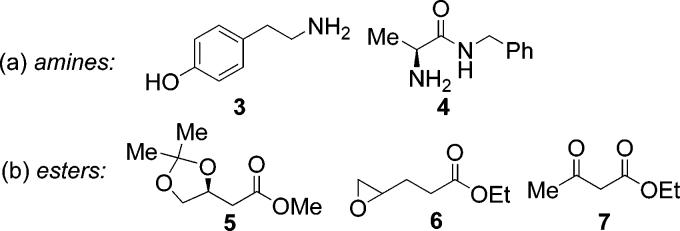

Although most ester–amide exchange reactions proceeded well for a variety of substrates, in initial experiments we have observed some limitations. For example, acidic phenols (cf. Figure 2, 3) were not tolerated due to their likely interaction with the zirconium catalyst. α-Amino amide 4 and β-alkoxy ester 5 showed low reactivity due to probable chelation between the substrate and catalyst. Ester–amide exchange of esters containing terminal epoxides such as 6 afforded a mixture of the desired epoxy-amide and amide in which epoxide ring-opening had occurred.19 Use of β-keto esters such as 7 led to clean formation of enamino esters which is well-precedented in the literature.20

Figure 2.

Substrate limitations.

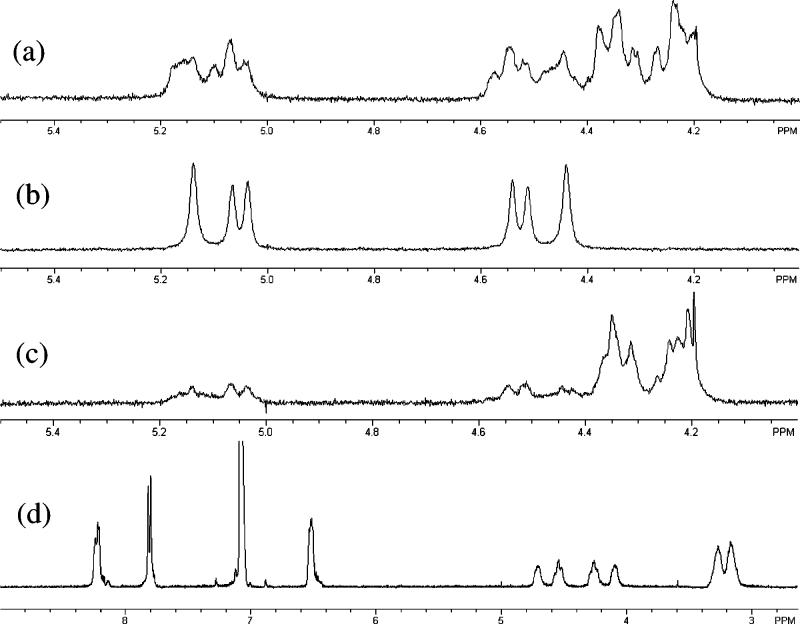

Figure 3.

1H NMR studies in benzene-d6. (a) Zr(Ot-Bu)4 + HOAt + PhCH2NH2 (1:1:1). (b) Zr(Ot-Bu)4 + HOAt + PhCD2NH2 (1:1:1). (c) Zr(Ot-Bu)4 + HOAt + PhCH2ND2 (1:1:1). (d) Zr(Ot-Bu)4 + HOAt + n-hexylamine (1:1:1).

Mechanistic Studies. (a) Preliminary NMR Studies. To gain insight into the reaction mechanism and role of additives in the Zr(Ot-Bu)4-catalyzed ester–amide exchange, we performed 1H NMR studies using HOAt as additive in benzene-d617 (Figure 3). The spectrum of HOAt was not available as a control due to its poor solubility in benzene-d6. However, when 1.0 equiv of Zr(Ot-Bu)4 was added to HOAt, peaks corresponding to the aromatic protons of HOAt appeared, indicating the formation of a soluble zirconium oxy-7-azabenzotriazolate (OAt) species via ligand exchange. Time-dependent experiments using Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt (1:1) revealed that the two sets of aromatic protons of HOAt reached equilibrium after approximately 5 h at room temperature with one dominant set observed shortly after mixing. Moreover, addition of 1.0 equiv of Zr(Ot-Bu)4 to benzylamine led to a downfield shift for the methylene protons of benzylamine from δ 3.48 to 3.83 which may be caused by coordination of benzylamine to the zirconium metal center. Further addition of HOAt (1.0 equiv) to the Zr(Ot-Bu)4–benzylamine (1:1) mixture resulted in formation of a series of downfield-shifted peaks (δ 4.23–5.14) (Figure 3a). Further experiments using α,α-dideuteriobenzylamine21 and N,N-dideuteriobenzylamine22 facilitated assignment of the N–H (δ 5.14, 5.05, 4.53, 4.44) (Figure 3b) and methylene protons (δ 4.34, 4.23) (Figure 3c). Use of n-hexylamine (Figure 3d) simplified the aromatic region in the 1H NMR spectrum indicating an apparent single 7-aza-1-oxybenzotriazolate species. Although a downfield shift of the methylene protons of benzylamine (δ CH2) 4.23 and 4.34) was diagnostic of the formation of a zirconium benzylamido species,19b,23 no definitive conclusion was made at this stage.

Interestingly, in contrast to our original hypothesis (vide supra), formation of an activated 1-oxy-7-azabenzotriazolate (OAt) ester was not observed after addition of methyl 3-phenyl-propionate (1.0 equiv) to a 1:1 Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt mixture in benzene-d6.17 Thus, our initial results indicated that the additive HOAt facilitates formation of zirconium amido or amine complexes (vide infra). Preliminary NMR experiments using HOBt and 2-hydroxypyridine (HYP) as additives were also performed in a similar manner. Comparable results were obtained for HOBt; however, neither a significant downfield shift of the methylene protons of benzylamine nor an active 2-pyridyl ester was observed using HYP as additive. Future experiments will address detailed mechanistic issues employing HYP as additive.

To further understand the catalytic system for ester–amide exchange, we performed 1H NMR experiments in benzene-d6 to monitor the reaction of methyl 3-phenylpropionate and benzylamine using 10 mol % Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt.17 During the reaction, signals corresponding to tert-butyl alcohol (δ CH3 = 1.08) appeared, and those corresponding to zirconium tert-butoxide disappeared. Similar results were also obtained by deliberate addition of MeOH into a mixture of Zr(Ot-Bu)4, HOAt, and benzylamine. The above results indicate that ligand exchange occurs between the byproduct methanol and the tert-butoxide ligand of the zirconium species during the reaction reinforcing the dynamic nature of the ester–amide exchange process.

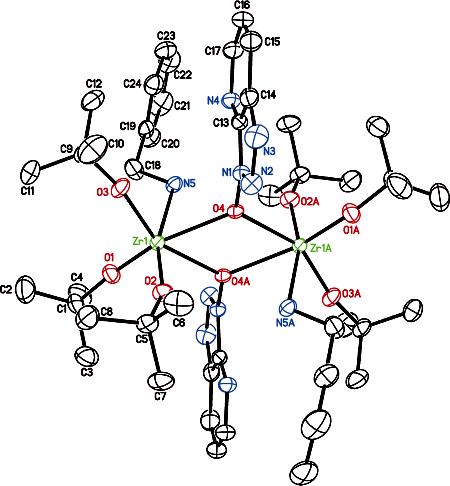

(b) X-ray Crystallography. During our NMR studies employing α,α-dideuteriobenzylamine (cf. Figure 3b), we serendipitously observed formation of crystals in NMR samples which were subsequently evaluated by single-crystal X-ray structure analysis. The molecular structure of 8 obtained by X-ray diffraction of the crystal obtained from a 1:1:1 mixture of Zr(Ot-Bu)4, HOAt and α,α-dideuteriobenzylamine is shown in Figure 4. The molecular structure shows a centrosymmetric dimer with two Zr(Ot-Bu)3(NH2CD2Ph) units bridged by two oxygen atoms of the OAt ligands. The Zr–N bond distance (2.41 Å) is also consistent with a Zr–NH2R species24 rather than a zirconium amido.23 More importantly, a crystal of the dimeric zirconium complex 8 was found to be catalytically active in the ester–amide exchange reactions. There is ample literature precedent for X-ray crystal structures of zirconium dimer complexes.25

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of dimeric zirconium species 8 with 50% probability ellipsoids. Selected bond distances (Å): Zr(1)–O(1) = 1.9147(15); Zr(1)–O(2) = 1.9386(14); Zr(1)–O(3) = 1.9233(15); Zr(1)–O(4) = 2.2881(14); Zr(1)–O(4A) = 2.2906(14); Zr(1)–N(5) = 2.4127(19). Selected angles (deg): O(1)–Zr(1)–O(4) = 154.71(6); O(2)–Zr(1)–O(4) = 89.42(6); O(3)–Zr(1)–O(4) = 94.15(6); O(4)–Zr(1)–O(4A) = 63.67(6); O(1)–Zr(1)–N(5) = 89.60(7); O(3)–Zr(1)–N(5) = 85.26(7); O(2)–Zr(1)–N(5) = 164.60(7); O(4)–Zr(1)–N(5) = 76.27(6); O(4A)–Zr(1)–N(5) = 76.89(6).

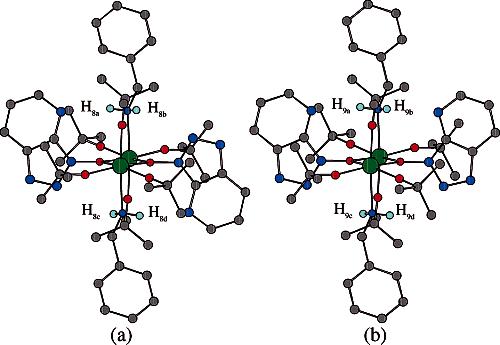

(c) Further NMR Studies. The X-ray crystal structure of 8 provides important insight into the 1H NMR spectrum of the zirconium complexes shown in Figure 3b. Regarding the predicted N–H proton patterns for the 1H NMR spectrum of 8 (cf. Figure 5a), the H8a and H8b protons are magnetically nonequivalent and likely account for the two coupled, doublet peaks at δ 5.05 and 4.53. The geminal coupling constant (Jab = 11.2 Hz) is similar to that reported for zirconium–amine complexes in the literature.24d At this point, we speculated that the downfield shift of the methylene protons of benzylamine is likely caused by the deshielding effect of the aromatic rings of the OAt ligands. We also suspected that the two additional singlet peaks in Figure 3b (δ 5.14 and 4.44) may be derived from additional zirconium species.

Figure 5.

Molecular model (Chem3D) of structure 8 (a) and proposed conformer 9 (b).

Further NMR experiments were conducted to understand the solution-phase zirconium catalyst structure.17 First, over a magnitude of concentration (0.005–0.05 M) or in the presence of varying amount of amine (1.0–5.0 equiv), 1H NMR spectra of Zr(Ot-Bu)4/HOAt/PhCH2NH2 (cf. Figure 3a) did not show any observable changes which rules out the possibility of an equilibrium between monomeric and multimeric zirconium species. Second, the 1H NMR spectrum of the mother liquor after crystallization of 8 was identical to homogeneous solutions of 8, which excludes the possibility of two distinct zirconium complexes which are not interconvertible at room temperature. On the basis of these results, we speculate that complex 8 is likely in equilibrium with conformer 9 (Figure 5b) which may be derived from 180° rotation of the N–O bond of 8. In proposed conformer 9, the two N–H protons on the same amine (H9a and H9b;H9c and H9d) are equivalent, but the N–H protons on different amines are nonequivalent, which is consistent with the observation of two singlet peaks in Figure 3b (δ 5.14 and 4.44).

Variable-temperature NMR experiments from −50 to +85 °C were conducted in toluene-d8 to support exchange between structures 8 and 9.17 Although coalescence was not reached for the NH protons even at 85 °C, apparent coalescence was observed for the aromatic protons ortho to the N atom of the OAt ligands. As the temperature increases, the two doublet peaks average progressively through coalescence to one doublet peak which represents the average line shape of 8 and 9. Moreover, two-dimensional T-ROESY26 exchange spectra were acquired at different temperatures.17 At 30 °C, exchange cross-peaks were observed between all possible amine hydrogen atoms (H8a–d and H9a–d) both within each conformer and between both conformers, while no cross-peaks were found below 0 °C. The relative intensity of the exchange cross-peaks, as well as the temperature-dependent behavior, strongly supports a dynamic process in solution phase between structures 8 and 9. Therefore, conformers 8 and 9 of the dimeric zirconium complexes are apparently the only catalyst forms found in a 1:1:1 mixture solution of Zr(Ot-Bu)4, HOAt, and benzylamine over a concentration range of 0.005–0.05 M.

At this stage, due to the anticipated high energy barrier for the simple N–O bond rotation mechanism, we speculate that N–O bond rotation occurs through a complex mechanism likely involving Zr–O or Zr–N bond dissociation/reassociation27 and nitrogen pseudorotation. Further studies will be needed to determine the operative mechanisms for this dynamic process.

(d) Kinetic Studies. To further understand the mechanism of the zirconium-catalyzed ester–amide exchange process, we performed preliminary kinetic studies using in situ FTIR spectroscopy28 by monitoring the reaction at room temperature between methyl 3-phenylpropionate and benzylamine. Because of the dynamic nature of the ester–amide process, initial rate kinetics was conducted to understand the catalyst and substrate behavior during a short beginning period in which the catalyst structure is assumed to be constant. In all cases, the initial rates under certain substrate and catalyst concentration were obtained by monitoring the formation of the product amide via the C=O stretch at 1681 cm−1. The reaction rate was found to exhibit first-order dependence on both ester and amine concentration at 5 mol % catalyst loading. The rate dependence on zirconium concentration was also found to be first order.17 This result, taken together with the fact that only dimeric zirconium species 8/9 were observed over a magnitude of concentration in the NMR spectroscopic studies, indicates that the active catalyst is likely the dimeric zirconium complexes 8/9 rather than a homolytic monomer.29

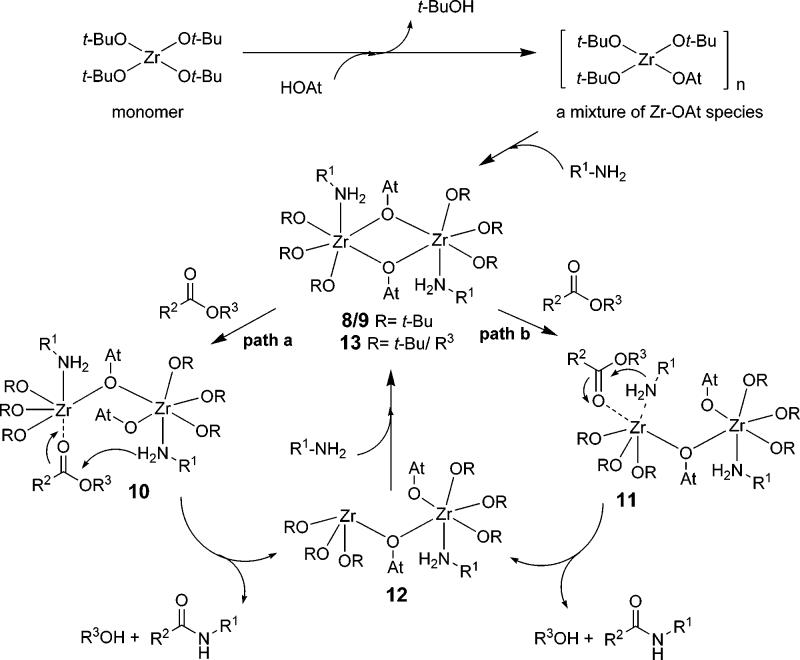

(e) Summary of Initial Mechanistic Studies. In line with the available mechanistic, structural, and kinetic data, we propose the generalized reaction pathway for ester–amide exchange as shown in Scheme 1. Ligand exchange of HOAt with tert-butyl alcohol results in a dynamic mixture of Zr–OAt species which may afford the dimeric zirconium species30 8 and 9 in the presence of amines. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the nitrogen atom of the OAt ligand and the amine NH31 may enhance the nucleophilicity of the amines and self-assembly to form dimers 8/9 in which both zirconium metal centers are hexacoordinate.24c,25b–d

Scheme 1.

Generalized Reaction Pathway

Coordination of an ester to one zirconium metal center32 results in formation of dimeric species 10 or 11 by breaking a bridging Zr–O bond. The amine in 10/11 then may attack the coordinated ester in an intramolecular fashion through a six-member (path a) or four-member (path b) transition state to afford the amide product. The OAt ligand may also serve as an internal general base33 to facilitate amide formation. Subsequent exchange of the tert-butoxide of the zirconium complex 12 by the byproduct alcohol in the presence of amines would regenerate the dynamic species 13 for further catalysis.

Conclusions

We have developed an efficient catalytic ester–amide exchange process by employing group (IV) metal alkoxides in conjunction with activators including HOAt, HOBt, and HYP. The reactions proceed smoothly over a wide range of structurally diverse esters and amines without removal of alcohol byproducts. Applications involving acid- or base-sensitive and complex substrates fully demonstrate the potential value of the methodology in the synthesis of complex molecules. Preliminary mechanistic studies on the Zr(Ot-Bu)4–HOAt system indicate that the active catalyst is likely a dimeric zirconium species based on X-ray crystallographic analysis. Further applications of the ester–amide exchange to complex molecule synthesis and additional mechanistic studies are currently in progress and will be reported in future publications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Professors Scott Schaus, John Caradonna, John Snyder, and Nolan McDougal (Boston University) and Professor John Turner and Mr. Mike Blanchard (University of Tennessee) for helpful discussions. We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM-62842) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (Unrestricted Grant in Synthetic Organic Chemistry, J.A.P, Jr.) for research support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds, including X-ray crystal structure coordinates for 8; X-ray crystallographic data (CIF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.(a) Basha A, Lipton M, Weinreb SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:4171. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang W-B, Roskamp EJ. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:6101. [Google Scholar]; (c) Williams JM, Jobson RB, Yasuda N, Marchesini G, Dolling U-H, Grabowski EJJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5461. [Google Scholar]; (d) Shimizu T, Osako K, Nakata T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:2685. [Google Scholar]; (e) Varma RS, Naicker KP.Tetrahedron Lett 1999406177references therein [Google Scholar]; (f) Kurosawa W, Kan T, Fukuyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8112. doi: 10.1021/ja036011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ishihara K, Kuroki Y, Hanaki N, Ohara S, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1569. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuroki Y, Ishihara K, Hanaki N, Ohara S, Yamamoto H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1998;71:1221. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Mader M, Helquist P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:3049. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishihara K, Ohara S, Yamamoto H.J. Org. Chem 1996614196references therein [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Srinivas KVNS, Das B. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:1165. doi: 10.1021/jo0204202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Ishihara K, Ohara S, Yamamoto H. Science. 2000;290:1140. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishihara K, Nakayama M, Ohara S, Yamamoto H.Tetrahedron 2002588179and references therein [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Otera J. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1449. Reviews: [Google Scholar]; (b) Grasa GA, Singh R, Nolan SP. Synthesis. 2004:971. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eldred SE, Stone DA, Gellman SH, Stahl SS.J. Am. Chem. Soc 20031253422and references therein [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogl EM, Gröger H, Shibasaki M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:1570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1570::AID-ANIE1570>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Greenwald RB, Pendri A, Zhao H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:915. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao H, Pendri A, Greenwald RB. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:7559. doi: 10.1021/jo981161c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.König W, Geiger R. Chem. Ber. 1970;103:788. doi: 10.1002/cber.19701030319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpino LA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:4397. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacs J, Kisfaludy L, Ceprini MQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:183. doi: 10.1021/ja00977a059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morley JS, Dutta AS. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1971;17:2896. doi: 10.1039/j39710002896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.König W, Geiger R. Chem. Ber. 1973;106:3626. doi: 10.1002/cber.19731060122. For use of N-hydroxy compounds as catalysts for aminolysis of activated esters, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Yamasaki S, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1256. doi: 10.1021/ja005794w. For representative catalytic methods employing Zr(Ot-Bu)4, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schneider C, Hansch M. Chem. Commun. 2001:1218. [Google Scholar]; (c) Okachi T, Murai N, Onaka M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:85. doi: 10.1021/ol027261t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kobayashi S, Ueno M, Saito S, Mizuki Y, Ishitani H, Yamashita Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307870101. references therein. For a review on zirconium alkoxides in catalysis, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yamasaki S, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:4066. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011001)7:19<4066::aid-chem4066>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Tangoulis V, Raptopoulou CP, Psycharis V, Terzis A, Skorda K, Perlepes SP, Cador O, Kahn O, Bakalbassis EG. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:2522. doi: 10.1021/ic991149i. For reports concerning metal–oxybenzotriazolate complexes, see: Copper: Nickel: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Diamantopoulou E, Raptopoulou CP, Terzis A, Tangoulis V, Perlepes SP. Polyhedron. 2002;21:2117. [Google Scholar]; (c) Diamantopoulou E, Perlepes SP, Raptis D, Raptopoulou CP. Transition Met. Chem. 2002;27:377. Manganese: [Google Scholar]; (d) Papaefstathiou GS, Vicente R, Raptopoulou CP, Terzis A, Escuer A, Perlepes SP. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002:2488. Vanadium and tin: [Google Scholar]; (e) Gordetsov AS, Zimina SV, Kulagina NV. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2001;71:1255. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Califano JC, Devin C, Shao J, Blodgett JK, Maki RA, Funk KW, Tolle JC. Peptides 2000, Proceedings of the 26th European Peptide Symposium. Montpellier, France: 2001. p. 99. [Google Scholar]; (b) Van Den Nest W, Yuval S, Albericio F. J. Pept. Sci. 2001;7:115. doi: 10.1002/psc.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ingenito R, Wenschuh H. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4587. doi: 10.1021/ol035742m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.See Supporting Information for further details

- 18.One exception is indicated in Table 3 (entry 11)

- 19.(a) Chakraborti AK, Kondaskar A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8315. For selected references concerning zirconium-mediated epoxide opening, see: [Google Scholar]; (b) Blum SA, Walsh PJ, Bergman RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14276. doi: 10.1021/ja037267t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Swamy RN, Goud VT, Reddy MS, Krishnaiah P, Venkateswarlu Y. Synth. Commun. 2004;34:727. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Maguire AR, Plunkett SJ, Papot S, Clynes M, O'Connor R, Touhey S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:745. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu Z, Alesso S, Pears D, Worthington PA, Luke RWA, Bradley M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2001:1947. doi: 10.1021/cc010045b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Agami C, Dechoux L, Hebbe S. Synlett. 2001:1440. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sleath PR, Noar JB, Eberlein GA, Bruice TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:3328. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prepared by hydrogen–deuterium exchange of benzylamine with CD3OD

- 23.(a) Frömberg W, Erker G. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985;280:355. For spectral characterization of zirconium benzylamido complexes, see: [Google Scholar]; (b) Gibson VC, Long NJ, Marshall EL, Oxford PJ, White AJP, Williams DJ. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001:1162. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cortright SB, Huffman JC, Yoder RA, Coalter JN, III, Johnston JN. Organometallics. 2004;23:2238. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Rogel F, Corbett JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8198. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ciruelos S, Cuenca T, Gómez R, Gómez-Sal P, Manzanero A, Royo P. Organometallics. 1996;15:5577. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen L, Cotton FA. J. Cluster Sci. 1998;9:63. [Google Scholar]; (d) Höltke C, Erker G, Kehr G, Fröhlich R, Kataeva O. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002:2789. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Mu Y, Piers WE, Macgillivray LR, Zaworotko MJ. Polyhedron. 1995;14:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans WJ, Ansari MA, Ziller JW. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1160. doi: 10.1021/ic981201v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fleeting KA, O'Brien P, Otway DJ, White AJP, Williams DJ, Jones AC. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1432. [Google Scholar]; (d) Patil U, Winter M, Becker H-W, Devi A. J. Mater. Chem. 2003;13:2177. [Google Scholar]; (e) Utko J, Przybylak S, Jerzykiewicz LB, Szafert S, Sobota P. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:181. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang T-L, Shaka AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:3157. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shao P, Gendron RAL, Berg DJ. Can. J. Chem. 2000;78:255. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Aggarwal VK, Sheldon CG, Macdonald GJ, Martin WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10300. doi: 10.1021/ja027061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Darensbourg DJ, Yarbrough JC, Ortiz C, Fang CC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7586. doi: 10.1021/ja034863e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kimura M, Seki M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3219. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cornell CN, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2796. doi: 10.1021/ja043203m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle TJ, Eilerts NW, Heppert JA, Takusagawa F. Organometallics. 1994;13:2218. For first-order kinetics of an active, dimeric titanium catalyst, see: [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCleland BW, Nugent WA, Finn MG. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6656. For examples of binuclear zirconium catalysts, see ref 14a and: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann F, Griehl C. J. Mol. Struct. 1998;440:113. For hydrogen bonding of the N atom of HOBt, see: [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Sobota P, Mustafa MO, Lis T. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989;377:69. For X-ray examples of zirconium-ester complexes, see: [Google Scholar]; (b) Young DA. J. Mol. Catal. 1989;53:433. [Google Scholar]; (c) Takahashi T, Xi C, Ura Y, Nakajima K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3228. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murakami A. Pept. Chem. 1980;17:89. For postulated general base catalysis in the aminolysis of HOBt esters, see: ref 9 and Horiki, K. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.