Abstract

The TREK-1 channel is a temperature-sensitive, osmosensitive and mechano-gated K+ channel with a regulation by Gs and Gq coupled receptors. This paper demonstrates that TREK-1 qualifies as one of the molecular sensors involved in pain perception. TREK-1 is highly expressed in small sensory neurons, is present in both peptidergic and nonpeptidergic neurons and is extensively colocalized with TRPV1, the capsaicin-activated nonselective ion channel. Mice with a disrupted TREK-1 gene are more sensitive to painful heat sensations near the threshold between anoxious warmth and painful heat. This phenotype is associated with the primary sensory neuron, as polymodal C-fibers were found to be more sensitive to heat in single fiber experiments. Knockout animals are more sensitive to low threshold mechanical stimuli and display an increased thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia in conditions of inflammation. They display a largely decreased pain response induced by osmotic changes particularly in prostaglandin E2-sensitized animals. TREK-1 appears as an important ion channel for polymodal pain perception and as an attractive target for the development of new analgesics.

Keywords: pain, potassium channel, TREK-1

Introduction

Ion channels play a very important role in the detection of pain (McCleskey and Gold, 1999; Julius and Basbaum, 2001; Wood et al, 2004; Bourinet et al, 2005). The TREK-1 channel is a member of the 2P-domain K+ channel (K2P) family, and it was the first mammalian mechanosensitive K+ channel to be identified at the molecular level (Patel et al, 1998). It is present in the peripheral sensory system, particularly in small dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Maingret et al, 2000) that are associated with nociception. It is axonally transported towards terminals in the sciatic nerve (Bearzatto et al, 2000). This channel also has a steep temperature sensitivity, between ∼15 and ∼40°C, making it a candidate for detection of cold and/or heat (Maingret et al, 2000) in addition to mechanical stimuli.

The TREK-1 channel is inhibited by agonists acting on both Gs and Gq receptors (Maingret et al, 2000; Chemin et al, 2003; Murbatian et al, 2005), and is therefore a natural target of mediators of pain that exert their action via these pathways such as PGE2 (Maingret et al, 2000; Moriyama et al, 2005) or serotonin (Chen et al, 1998).

The first purpose of this work was to examine in detail the exact localization of the TREK-1 channel in the different subtypes of sensory neurons, especially in relation with TRPV1, an Na+ and Ca2+ permeable channel expressed in small diameter DRG neurons associated with the detection of noxious heat (Caterina et al, 1997; Julius and Basbaum, 2001) and activated by the noxious ligand capsaicin (Caterina et al, 1997; Voets et al, 2004).

The second purpose of this work was to make use of TREK-1 knockout mice to evaluate the exact role of this temperature-, mechano- and osmo-sensitive K+ channel in pain perception associated with these different types of stimuli.

Results and discussion

TREK-1 localization in sensory neuron subtypes

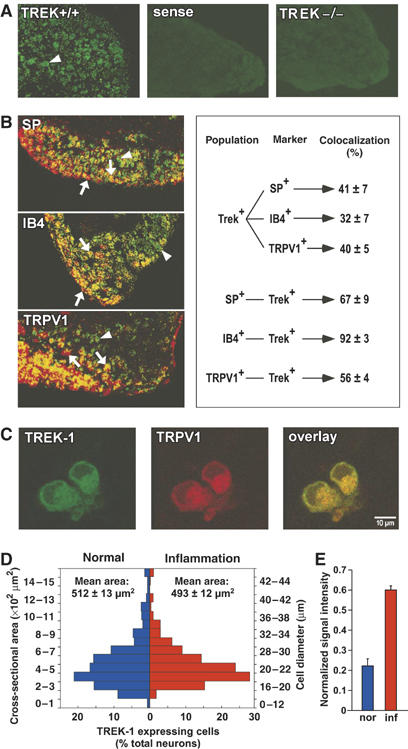

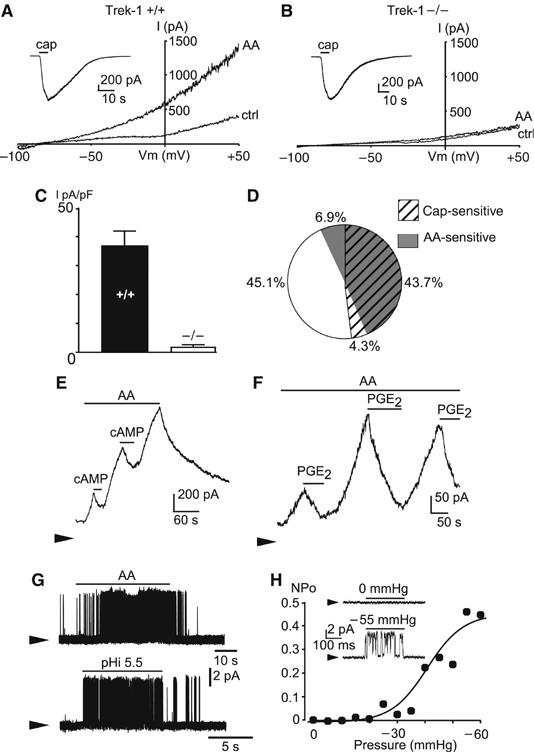

The localization of TREK-1 positive sensory neurons in DRG is shown in Figure 1. Sixty percent of sensory neurons express TREK-1 mRNA in normal conditions. These neurons have a mean cell body area of 512±13 μm2 (Patel et al, 1998; Maingret et al, 2000), corresponding to diameters from small to medium-large (i.e. from 15 to 35 μm) (Figure 1D). Among these neurons, 41±7% are associated with peptidergic substance P (SP)-positive fibers and 32±7% are associated with nonpeptidergic IB4-positive C-fibers (Figure 1B). Moreover, 40±5% of the DRG neurons that express TREK-1 also express the thermal sensor TRPV1 (Figure 1B), and ∼60% of the neurons that express TRPV1 also express TREK-1. Reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR reveals that inflammation produces a 3.0±0.7-fold increase of TREK-1 mRNA level (Figure 1E) with no change in the neuronal distribution of TREK-1 mRNA (Figure 1D). Immunological techniques that previously indicated the predominant presence of TREK-1 in small sensory neurons (Patel et al, 1998; Maingret et al, 2000) also indicate an extensive colocalization of TREK-1 and TRPV1 in DRG neurons in culture (Figure 1C). Real-time quantitative RT–PCR analysis (Supplementary Figure 1) indicates that deletion of the TREK-1 gene does not drastically alter expression levels of the different thermosensors of the TREK/TRAAK family or of the TRP family in DRG neurons. This coexpression of TREK-1 and TRPV1 is fully confirmed by electrophysiological studies. Direct electrophysiological demonstration of the presence of TREK-1 in small diameter DRG neurons, considered as C-fiber nociceptors (capacitance <30 pF), is presented in Figure 2. Large capsaicin-sensitive currents (Figure 2A and B, inset) were recorded from both TREK-1+/+ (in 48% of the recorded neurons, Icapsaicin=1491±399 pA, n=30) and TREK-1−/− mice (in 53% of the recorded neurons, Icapsaicin=1085±334 pA, n=21). The deletion of TREK-1 does not bring a significant change in currents induced by capsaicin (P=0.47, t-test). To avoid contamination by Na+ or Ca2+ currents, the holding potential was normally maintained at 0 mV or long-lasting voltage ramps were used to inactivate these currents. TREK-1 is potently activated by arachidonic acid (AA) and this property was used for channel identification (Fink et al, 1996; Patel et al, 1998; Fioretti et al, 2004). An AA-activated K+ channel was recorded from 50.6% of wild-type DRG neurons (IAA=36.5±5.3 pA/pF, n=30) but was not observed in DRG neurons from TREK-1−/− mice (n=21; Figure 2A and B). In TREK-1+/+ DRG cells in culture, TREK-like currents were expressed in as many as ∼90% of the capsaicin-sensitive neurons (Figure 2D, n=63). As expected for a TREK-1 channel (Patel et al, 1998; Maingret et al, 2000), AA-activated currents in TREK-1+/+ DRG neurons were reversibly inhibited by cAMP (inhibition: 56.6±8.2%, n=12) (Figure 2E) as well as by PGE2 (Figure 2F; inhibition: 50.2±4.4%, n=15). Another property for the identification of TREK-1 is its ability of being potently activated by intracellular acidification (Bearzatto et al, 2000). A K+ channel activated by intracellular acidification with properties similar to recombinant TREK-1 (Maingret et al, 1999) is observed in TREK-1+/+ DRG neurons (Figure 2G). The mechanosensitivity of this particular channel is shown in Figure 2H. Other electrophysiological properties of DRG neurons from TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice are presented in Supplementary Table I. These results do not reveal changes of membrane potential associated with TREK-1 deletion in mice DRGs in culture. They probably mean that other K+ channels are more important than TREK-1 in imposing the resting potential of the cell body, but the cell body is most probably distinct in its properties from the free nerve terminal that serves as the primary detector of pain stimuli, particularly heat. In addition, DRG neurons in culture probably do not reflect the exact in vivo situation. It is for all these reasons that we decided to analyze potential differences between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice using a skin-nerve preparation (see below).

Figure 1.

TREK-1 mRNA expression in sensory neurons. (A) TREK-1 mRNA localization in DRG of wild-type mice with an antisense probe (TREK+/+) and a control sense probe (sense), and in DRG of knockout mice with an antisense probe (TREK−/−) showing labeled neurons in green (as indicated by an arrowhead). (B) TREK-1 mRNA colocalization with SP, isolectin B4 (IB4) and TRPV1. TREK-1 mRNA labeling appears in green and other markers in red. Coexpressing neurons appear in yellow. A downward pointing arrow shows a double-labeled neuron, an arrowhead a TREK-1 expressing neuron and an upward pointing arrow indicates an SP-, IB4- or TRPV1-labeled neuron. The diagram on the right side indicates the percentage of coexpressing cells in each neuronal population in normal conditions. (C) The representative picture of TREK-1 (green) identified with a previously described antibody (Maingret et al, 2000) and TRPV1 (red) channels expression shows a colocalization (yellow) in small neuron bodies in DRG neurons in culture. (D) Distribution of TREK-1 mRNA positive neurons relative to their cross-sectional area and diameter in both normal and inflammatory conditions; n=3–4 mice, with at least 400–600 cells counted per condition. (E) Semiquantitative RT–PCR results of TREK-1 mRNA levels in normal (nor) and inflammatory (inf) conditions expressed as signal intensity normalized to actin control (n=3 mice).

Figure 2.

TREK-1 like currents in mouse small diameter DRG neurons. (A) Activation of TREK-1 like currents by 10 μM AA in DRG neurons from TREK-1+/+ mice. Currents were elicited by voltage ramps of 1 s duration, from −100 to +50 mV. Holding potential was −80 mV. Results were obtained in the whole-cell configuration and at room temperature (20–22°C). Inset: Capsaicin-sensitive currents recorded at −50 mV (elicited by 10 μM capsaicin, cap) in the same neuron. (B) The absence of AA-activated currents in DRG neurons from TREK-1−/− mice (same experiments as in (a)). (C) Mean density of AA-sensitive currents (measured at 0 mV) in capsaicin-sensitive DRG neurons from TREK-1+/+ (n=30) and TREK-1−/− mice (n=21). (D) Percentage of small diameter DRG neurons expressing capsaicin- and AA-sensitive currents from TREK-1+/+ mice (n=63). (E) Activation of TREK-1 like potassium currents by 10 μM AA and inhibition by 500 μM CPT-cAMP in TREK-1+/+ DRG neurons. Membrane potential was 0 mV, the zero current is indicated by an arrow, results shown are typical of 12 experiments. (F) Activation of TREK-1 like potassium currents by 10 μM AA and inhibition by 5 μM PGE2 in TREK-1+/+ DRG neurons. Membrane potential was 0 mV, results shown are typical of 15 experiments. (G) Activation of TREK-1 like currents by 10 μM AA and pH 5.5 in inside-out patches from TREK-1+/+ mouse DRG neurons. Membrane potential was 0 mV, results shown are typical of 18 experiments. (H) Dose–response curve for TREK-1 like current activation (inside-out configuration) by membrane stretch (NPo was calculated assuming a single channel current of 5 pA at 0 mV). Inset: Reversible activation of the native current by a membrane stretch to −55 mmHg. Membrane potential was 0 mV, results shown are typical of five experiments.

TREK-1 is a member of a subfamily that includes TREK-2 and TRAAK that are also mechanosensitive (Patel et al, 2001), temperature sensitive (Kang et al, 2005) and expressed in DRG neurons (Medhurst et al, 2001; Talley et al, 2001; Kang and Kim, 2006). Analysis of channel conductances has suggested that TREK-2 is probably the most highly expressed of these three channels in rat DRGs from neonatal animals maintained in culture in the presence of NGF (Kang et al, 2005). It may be that different animal species, at different stages of development (we use 7–10-week-old mice), in different culture conditions (we are not exposing DRG neurons to NGF) might express primarily different types of K2P channels. It may also be that TREK-1 and TREK-2 have the capacity to form heterodimers as previously observed for TASK subunits (Czirjak and Enyedi, 2002).

TREK-1 contribution to peripheral C-fiber nociceptor thermosensitivity

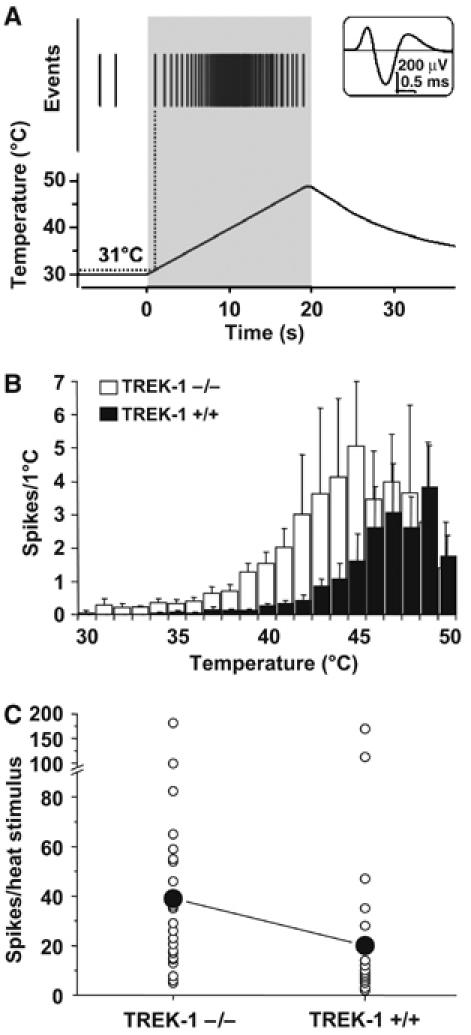

TREK-1 contribution to peripheral C-fiber heat nociceptor was tested using the isolated skin-saphenous nerve preparation (Reeh, 1986). Single action potentials from slowly conducting velocity (CV <1.2 m/s) C-fibers were recorded and their receptive fields in the skin were probed for their modal sensitivity (Kress et al, 1992). Figure 3A shows individual C-fiber response to noxious heat. The threshold for heat induced spike firing is 36.5±0.8°C (n=24) for TREK-1−/− mice and 41.7±0.7 (n=28) for TREK-1+/+ mice (P<0.001, t-test). Nociceptors from TREK-1−/− mice showed much larger responses than TREK-1+/+. They fire more action potentials in response to heat (heat ramps from 30 to 50°C in 20 s; TREK-1−/− 39±8 spikes, n=24; TREK-1+/+ 20±7 spikes, n=28; P<0.001, one-tailed Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U-test) (Figure 3C). The difference between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice is most pronounced at temperatures between 30 and 45°C (Figure 3B). This indicates the important role of the TREK-1 channel in C-fiber sensing in this temperature range that corresponds closely to the temperature range (30–45°C) at which we observed major increases of TREK-1 activity (Maingret et al, 2000). At temperatures above 45°C, differences between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice are abolished. In addition, C-fibers from knockout mice did not show a significant difference with normal mice in spike firing in response to a challenge to cold temperature (31–10°C in 60 s; TREK-1−/− 13±2 spikes, n=10; TREK-1+/+ 9±2 spikes, n=23; P>0.05, U-test) (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Heat responses of saphenous nerve C-fibers with receptive fields in isolated hairy skin of TREK-1−/− mice are increased. (A) A representative original recording showing action potentials in response to noxious heat in a single fiber from a TREK-1−/− mouse. Top inset shows an average of 643 action potentials recorded from a CMH unit (conduction velocity 0.46 m/s, von Frey threshold 16 mN). The top of the trace illustrates action potentials (Events), depicted as vertical bars, in response to heat stimulus (lower trace) applied on the chorion side of the skin. (B) Averaged histograms of heat responses of mechano-heat sensitive C-fibers of TREK-1+/+ (n=28, dark bars) and TREK-1−/− (n=24; white bars). Action potentials are binned per °C. (C) Total number of action potentials per heat stimulus across n=24 experiments for TREK-1−/− (white circles, left column) and n=28 experiments for TREK-1+/+ mice (white circles, right column). Means are dark circles.

TREK-1 deleted mice are more sensitive to a variety of pain stimuli

After showing that the TREK-1 channel is present in sensory neurons associated with nociception, the next question was to analyze the sensitivity of TREK-1−/− mice to a variety of pain stimuli.

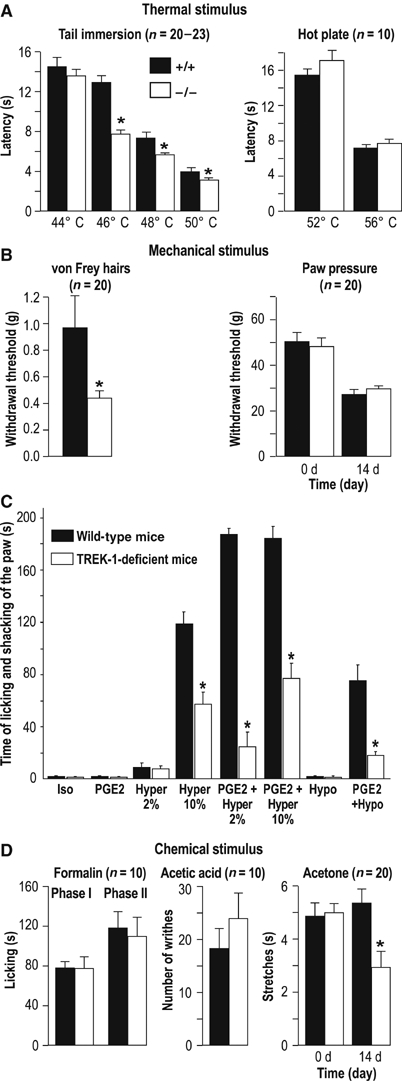

TREK-1−/− mice were hypersensitive to thermal pain. They behaved like TREK-1+/+ mice at 44°C, but they displayed a faster reaction time to withdraw their tail from hot temperature baths at 46, 48 or 50°C (Figure 4A). At higher temperatures (52 or 56°C) in the hot plate test, there was no difference between the two groups (Figure 4A). There are actually two types of noxious heat responses according to sensing fiber types. The first one corresponds to a moderate activation threshold near 40°C, that is, in the range at which we perceive a shift from anoxious warmth to noxious heat. The second one is associated with fibers that respond to a higher threshold (>50°C), and which probably use the TRPV2 channel as a heat detector (Caterina et al, 1999). The easiest explanation of our results is that TREK-1 is mainly associated with the function of the lower threshold fibers, the fibers that have been recorded in Figure 3. Removal of the TREK-1 channel exacerbates responses to heat between 30 and 45°C in the C-fibers experiments and in a window of temperatures between 45–46 and 50–51°C in the tail immersion assay. The temperature ranges in the two assays are not exactly the same, but this is not very surprising as (i) it is likely that bath temperature in the tail immersion assay does not exactly reflect the temperature at C-fiber terminals in the tail dermis and epidermis. In the skin-nerve assay, the warmth fluid is applied directly on the chorion side of the skin; (ii) the tail immersion test corresponds to an integrated physiological response not necessarily linearly related to responses in the peripheral C-fibers.

Figure 4.

Comparison of nociceptive behavior of TREK-1+/+ (black bars) and TREK-1−/− (white bars) mice to noxious (a, b, d) and osmotic (c) stimuli. (A) Withdrawal and paw licking latencies to noxious thermal stimulus (tail immersion test, hot plate test, respectively) are given as mean±s.e.m. (B) Paw withdrawal thresholds (mean±s.e.m) to mechanical stimulation were determined with the von Frey test (performed in healthy mice) (left) and the paw pressure assay in TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice. The paw pressure test was performed before (0 day) and after (14 days) sciatic nerve ligation. (C) In the flinch test (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003, 2005), Iso corresponds to injection of 10 μl of isotonic solution (0.9% NaCl) in the hindpaw, Hypo to an injection of 10 μl of hypotonic solution (deionized water), Hyper to an injection of 10 μl of hypertonic solution (2 or 10% NaCl). PGE2 (100 ng/paw) was injected alone or 30 min prior to the hypotonic or hypertonic stimulus. (D) Response (mean±s.e.m.) to chemical stimuli; duration of licking and biting the hindpaw induced by formalin, number of abdominal writhings induced by acetic acid and duration of acetone-induced hindpaw stretches. Acetone experiments were carried out on non-neuropathic animals (0 day) as well as on mononeuropathic mice, 14 days after sciatic nerve ligation. P<0.05 versus wild-type animal on TREK-1+/+ animal scores, n=10–20 per group.

The next step was to compare responses of TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice to mechanical stimuli. The first analysis was made by touching the skin with von Frey hairs of increasing stiffness, which exert defined levels of force as they are pressed into the plantar surface of the paw. TREK-1−/− mice were much more sensitive to this type of mechanical stimulus than TREK-1+/+ mice (Figure 4B). The withdrawal threshold decreases from 0.97 to 0.43 g in TREK-1−/− mice. This is even lower than the withdrawal threshold of 0.60±0.01 g (n=8) measured in mononeuropathic TREK-1+/+ mice 14 days after ligature. These results suggest that TREK-1 deletion results in allodynia in this range of mechanical stimulus. We next exposed the mice to the paw pressure assay (Randall and Selitto, 1957), which involves a stronger mechanical stimulus. In that case responses of TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice were essentially the same (Figure 4B).

All these results taken together suggest that TREK-1 is important in nociceptors for the perception of low-threshold but not high-threshold thermal and mechanical stimuli.

The extensive colocalization of TREK-1 and TRPV1 channels (that can reach up to ∼90% in small DRG neurons in culture (Figure 1C)) is particularly striking and interesting since capsaicin-sensitive primary afferents are known to have an important role in heat pain in man (Khalili et al, 2001). It may provide an explanation for the observed role of TREK-1 in C-fiber thermosensitivity, particularly between 40 and 45°C (Figure 3). This explanation would be that in most capsaicin-sensitive TRPV1 containing nociceptors, the depolarization induced by TRPV1 is compensated or controlled, in this limited range of temperature, by a hyperpolarizing contribution of TREK-1. The different temperature dependences of TRPV1 (a threshold near 40°C and then a steep increase of activity at higher temperatures at least to 48–50°C (Caterina et al, 1997; Tominaga et al, 1998)) and of TREK-1 (an activity that starts near 30°C and then strongly peaks at about 42–45°C) would define a sensory window near the threshold for thermal pain. However, the role of TRPV1 as a major pain thermosensor (Caterina et al, 1997) has been recently discussed (Woodbury et al, 2004). It might be that other thermosensors are also involved, probably also from the TRP channel family (Guler et al, 2002; Nilius et al, 2003). The same type of mechanism could also hold for mechanosensitivity. Most C-fiber nociceptors are polymodal receptors that respond to both noxious mechanical and thermal stimuli, and many of these mechano-heat sensitive nociceptors are also activated by capsaicin (Szolcsanyi et al, 1988; Drew et al, 2002). The nonselective mechanosensitive ion channels that function as mechanosensors have not yet been definitely identified at a molecular level although they may well also belong to the TRPV channel family (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003). We propose that it is the balance between the respective contributions of the nonselective mechanosensitive channels with their depolarizing effect and the mechanosensitive K+ channel TREK-1 with its hyperpolarizing effect that determines nociceptor excitability in response to relatively low threshold mechanical stimuli.

Osmotic stimuli excite nociceptors and can produce high levels of pain sensation after sensitization with PGE2 (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003, 2005). Injection of mild hypertonic saline stimulates C-fiber afferents, and is used as a model of muscle and joint pain in humans (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2005). We have used two levels of hypertonicity by injecting either 2% NaCl (607 mOsm) or 10% NaCl (3250 mOsm) in the hind paw of mice. As it can be seen from Figure 4C, there are large differences between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice in pain perception associated with the highest level (10%) of hypertonicity, TREK-1−/− mice being less sensitive than control mice. The lower level of hypotonicity (2%) produces a milder pain sensation that does not appear to be different in TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice. However, as previously described by Alessandri-Haber et al (2005) sensitization with PGE2 considerably increases pain perception associated with intradermal injection of 2% NaCl. TREK-1−/− mice experience a much lower level of pain sensation than TREK-1+/+ mice in this experimental situation that mimicks some of the aspects of inflammatory pain. Sensitization with PGE2 also increases pain perception produced by 10% NaCl and again TREK-1+/+ mice are much more sensitive than TREK-1−/− mice. This difference between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice is also marked for pain associated with hypo-osmotic stimuli appearing after PGE2 treatment (Figure 4C). TRPV4, a channel from the TRP family, is involved in osmotic perception (Liedtke and Friedman, 2003; Liedtke et al, 2003), and has been reported to be important for pain perception associated with both hyper and hypo-osmotic stimuli (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003, 2005) particularly after PGE2 sensitization. It is striking to observe that mice lacking the TRPV4 channel are similar in their phenotype, with respect to pain, to mice lacking the TREK-1 channel (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003, 2005) in being much less sensitive to painful osmotic stimuli. Therefore, it is tempting to propose that TRPV4 and TREK-1 work in concert to sense painful stimuli associated with osmolarity disturbances, at least after exposure to PGE2, but of course more work is needed to prove this point directly since other channels from the TRP family might also be candidates for this function. An interesting observation is that sensitivity to osmolarity changes in small diameter sensory neurons is present in capsaicin-sensitive nociceptors (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003), which, as shown in this work, also express the TREK-1 channel.

TREK-1 has also been considered as a possible candidate for cold sensing (Maingret et al, 2000; Reid and Flonta, 2001; Viana et al, 2002). We have observed no difference between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice in their sensitivity to cold induced by a drop of acetone (Kontinen et al, 1999) to the dorsal surface of the paw. This is consistent with the previously discussed results of C-fiber recordings (Supplementary Figure 2). This is also consistent with the lack of difference observed in the tail immersion assay between 44 and 5°C (not shown). However, a decreased sensitivity to acetone is observed in the TREK-1−/− animals when mice are made mononeuropathic (Figure 4D), suggesting that TREK-1 then becomes involved in cold sensing. This particular point will have to be explored further since neuropathic pain patients exhibit both cold allodynia and cold hyperalgesia (Woolf and Mannion, 1999).

Other painful chemical stimuli such as those induced by subcutaneously injected formalin or by acetic acid injected in the peritoneal cavity to activate visceral nociceptors failed to reveal a difference between TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice (Figure 4D).

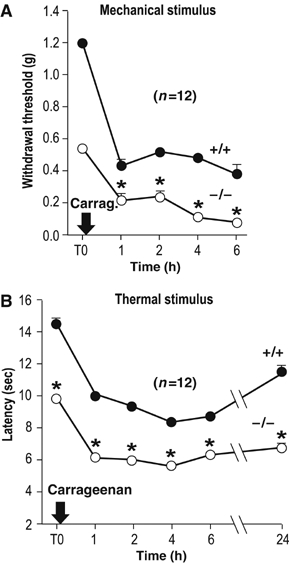

The key role of TRPV1 and by consequence of TRPV1-expressing nociceptors in inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia is well established (Julius and Basbaum, 2001). The heat response of TRPV1 is drastically shifted towards lower temperatures by a number of mediators associated with tissue injury and inflammation and in particular by bradykinin (Cesare et al, 1999; Prescott and Julius, 2003; Moriyama et al, 2005). PGE2, which is a major inflammatory mediator, has been shown to sensitize TRPV1 via PKA/PKC pathways, lowering the temperature threshold for TRPV1 activation below 35°C (Moriyama et al, 2005). We previously showed that cAMP via kinase A leads to an inhibition of TREK-1 (Patel et al, 1998). We have shown in the present work that this inhibitory effect occurs in capsaicin-sensitive DRG neurons exposed to PGE2 (Figure 2F). Both TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice, injected intraplantarly with carrageenan to produce inflammation showed thermal hyperalgesia (46°C—Figure 5A). Mechanical hyperalgesia in carrageenan-treated TREK-1+/+ and TREK-1−/− mice in response to tactile stimuli was also observed (Figure 5B). The carrageenan-induced decrease in reaction scores was lower in TREK-1−/− mice, suggesting that TREK-1 is, at least in part, involved in the peripheral sensitization of nociceptors due to inflammation. Mediators of pain acting at receptors that are coupled to Gs proteins such as PGE2 (Maingret et al, 2000) or to Gq proteins (Chemin et al, 2003) will produce an inhibition of TREK-1. It is particularly interesting to note that the same types of mediators are potent sensitizers of TRPV1 (Moriyama et al, 2005).

Figure 5.

Compared mechanical and thermal inflammatory hyperalgesia of TREK-1−/− (white circle) and TREK-1+/+ (black circle) mice. Withdrawal thresholds to tactile stimulation (von Frey filaments) of the right hindpaw (A) and withdrawal latencies to noxious thermal stimulus (right hindpaw immersion, 46°C) (B) were determined before and after injection of carrageenan in the right hindpaw. P<0.05 compared to TREK-1+/+ mice, n=12 per group.

Conclusion

This work shows that the TREK-1 channel is involved in the perception of various painful stimuli, and it will be interesting to analyze the functions associated with parent K2P channels such as TREK-2 and TRAAK channels that are also expressed in DRG neurons using TREK-2−/− and TRAAK−/− mice. Our results also suggest that noxious heat, and/or mechanical and osmotic sensitivity is not strictly associated with a specific transduction macromolecule, but rather results from a delicate combination of ionic channels expressed in particular subsets of sensory neurons. The observation that the TREK-1 channel is important for painful thermal perception near the threshold between anoxious warmth and noxious heat and is more generally involved in polymodal pain sensations makes it possible that an abnormal function and/or regulation of this particular K+ channel is involved in a variety of pain states in humans. Thus, TREK-1 appears as an interesting potential target for the development of new analgesics.

Materials and methods

In situ hybridization

L4-6 DRG sections (12 μm) were fixed and hybridized (52°C) with 5 ng/μl biotinylated antisense oligonucleotide (same as the antisense oligonucleotide used in PCR) in 12.5% formamide, 4 × SSC, 2.5 × Denhardt's solution, 250 μg/ml herring sperm DNA. TREK-1 expressing cell distribution was performed with NIH 1.2 image software on diaminobenzidine-labeled slides and revealed with Dako GenPoint kit. Fluorescent detection of TREK-1 transcripts was carried out with an ELF-97 mRNA in situ hybridization kit (Molecular Probes).

TREK-1, SP and TRPV1 immunochemistry and IB4 binding

After in situ hybridization, slides were treated with anti-SP (1:200; Sigma) or anti-TRPV1 (1:1000; Abcam or 1:400, Chemicon) antibodies and revealed with anti-IgG Alexa 594-coupled antibodies (1:400; Molecular Probes). FITC-coupled IB4 was applied at 12.5 μg/ml, and the green signal turned to red with Adobe PhotoShop 5.0 before superimposition with TREK-1-labeled pictures. Immunohistochemical specificity was assessed by omitting primary antibodies (data not shown).

For colocalization experiments in DRG neurons, cells were cultured in the same conditions as for electrophysiology experiments. The cells were fixed in 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.3% Tween-20/PBS, blocked with 5% horse serum/PBS for 2 h at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-TREK-1 antibody (Maingret et al, 2000) (1:15000) overnight. The cells were then incubated with anti-IgGAlexa 488-coupled antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in 5% normal goat serum for 1 h. Afterward, the cells were incubated with a goat polyclonal TRPV1 antibody (Santa Cruz, diluted 1/300) in 5% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-IgGAlexa 595-coupled antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Labeling was visualized using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Imaging photomicroscope.

RT–PCR experiments

Total RNA (2 μg) from L4-6 DRGs was reverse-transcribed (First-strand cDNA synthesis kit, Amersham). One-tenth was used per PCR condition. Results were analyzed with the NIH 1.2 Image program and normalized with β-actin signal. Primers used were (5′–3′, sense/antisense): TREK-1 TCAAGCACATAGAAGGCTGG/ACGGATGTGGCAG CGTGG, β-actin GTGCCCATCTATGAGGGTTACGCG/GGAACCGCT CATTGCCGATAGTG.

Mice

All experiments were performed on 20–24 g male mice of the N10F2 backcross generation to C57Bl/6J congenic strain. The detailed experimental methodology used to generate and genotype TREK-1 knockout mice has been previously described (Heurteaux et al, 2004). We observed no compensatory upregulation of genes for other neuronal K2P channels in DRGs of TREK-1−/− mice particularly those that are closest in structure to TREK-1 such as TREK-2 and TRAAK (Supplementary Figure 1), as also previously demonstrated by us in brain and cerebellum (Heurteaux et al, 2004). TREK-1−/− mice also express essentially unchanged levels of TRP channels, TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPV4, that have been associated with thermal perception (Supplementary Figure 1). All mice were acclimatized to the laboratory conditions for at least 1 week prior to testing. They were housed in grouped cages in a temperature-controlled environment with food and water ad libitum. The behavioral experiments were performed blind to the genotype, in a quiet room, by the same experimenter for a given test taking great care to avoid or minimize discomfort of the animals. Unilateral peripheral mononeuropathy (Bennett and Xie, 1988) was induced in mice anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) with four chromic gut (5–0) ligatures tied loosely (with about 1 mm spacing) around the common sciatic nerve. The nerve was constricted to a barely discerning degree, so that circulation through the epineural vasculature was not interrupted. All experiments were conducted following the Guidelines of the Committee for Research and Ethical Issue and in full compliance with institutional regulation on animal care and use.

Electrophysiological recordings

DRG neurons were obtained from 7- to 10-week-old wild type (C57Bl/6J) and TREK-1−/− mice. Patch-clamp experiments were performed 4 days after plating. External solution contained (in mM): 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 glucose and 10 mM TEACl, 3 mM 4AP and 10 μM glibenclamide (pH 7.3 adjusted with NaOH, 300 mOsm). After dissection and enzymatic trituration, DRG neurons were plated in 35 mm Petri dishes previously coated with poly-(L)-lysine (Sigma) and cultivated in Ham F12 complemented with 10% inactivated foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Patch pipettes had a resistance of 1.5–2.5 MΩ when filled with (mM) 155 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH, 310 mOsm). AA and PGE2 were dissolved at 100 mM in ethanol, diluted in the saline solution and sonicated 15 min on ice.

Skin nerve preparation and single-C fiber electrophysiology

The mouse isolated skin-saphenous nerve preparation and the single-fiber recording technique were previously described (Reeh, 1986; Kress et al, 1992). In brief, the skin of the lower hind paw of male mice was dissected subcutaneously together with the attached saphenous nerve. The skin was placed inside-up in an organ chamber and superfused (16 ml/min) with temperature controlled (30±1°C) carbogenated synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF). SIF composition was in mM: 107 NaCl, 3.48 KCl, 26.2 NaHCO3, 1.67 NaH2PO4, 0.69 MgSO4, 9.64 Na-gluconate, 5.5 glucose, 7.6 sucrose, 1.53 CaCl2, pH 7.4 with O2/CO2—95%/5%. Action potentials from isolated C-fiber placed on a gold wire recording electrode were recorded extracellularly. The mechanosensitivity of isolated C-units was characterized by stimulation of their receptive fields with a set of von Frey filaments calibrated from 1 to 256 mN. The median threshold was 22.6 mN (n=28 for TREK-1+/+ and n=24 for TREK-1−/−). The electrical threshold and conduction velocity of each fiber were determined. A cutoff velocity of 1.2 m/s was used to distinguish between myelinated and unmyelinated nociceptors. The receptive field was isolated with a metal ring (200–300 μl internal volume) positioned on the chorion. Noxious heat (30–50°C in 20 s) was applied with a custom made temperature-controlled superfusion system positioned inside the ring (Conrad Electronic, Hirschau, Germany). Cold perfusion was from 30±1 to 11±1°C in 60 s. Threshold for noxious heat or cold responses was admitted as the temperature at which the first spike discharged during the superfusion. The signal was band pass filtered between 100 and 2 kHz, digitized (40 kHz) and further analyzed with the template-based discrimination software DAPSYS (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA). Statistical analysis Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U-test. Numbers are mean±s.e.m.

Mechanical sensitivity

Allodynia was assessed using calibrated von Frey filaments (0.0045–5.4950 g). The filaments, tested in order of increasing stiffness, were applied five times, perpendicularly to the plantar surface of hindpaw and pressed until they bent. The first filament which evoked at least one response was assigned as the threshold (Tal and Bennett, 1994).

The paw pressure test was used as described by Randall and Selitto (1957), by applying increasing pressure to the right hind paw until a paw withdrawal threshold was obtained.

Acetone test

The behavioral signs of cold sensitivity after application of a drop (50 μl) of acetone on the dorsal surface of the right hindpaw (Kontinen et al, 1999) were a sharp withdrawal of the hindpaw. The duration (>1 s) of this behavior was used as a pain parameter.

Hot-plate test

Mice remained on the plate (56°C) until they started licking their forepaws, the latency was taken as a pain parameter (cutoff time: 20 s).

Tail-immersion test

The tail was immersed in a water bath until withdrawal was observed (cutoff time: 30 s) (Janssen et al, 1963). Two separate withdrawal latency time determinations were averaged. A range of different temperatures (0–50°C) was tested.

Writhing test

Acetic acid (0.6% solution, 10 ml/kg) was injected into the peritoneal cavity, wherein it activates nociceptors directly and/or produces inflammation of visceral (subdiaphragmatic organs) and subcutaneous (muscle wall) tissues (Siegmund et al, 1957). The number of these abdominal writhings, determined during 15 min after the injection of the irritant, was used as a pain parameter.

Formalin test

This test (Murray et al, 1988) evaluates behavioral responses to the subcutaneous injection of formaldehyde. Fifteen microliters of 5% formalin was injected subcutaneously into the plantar surface of the right hindpaw. The total time spent in licking and biting the right hindpaw over the next 60 min was determined and used as a pain parameter.

Flinch test

As previously described (Alessandri-Haber et al, 2003, 2005), mice were acclimated for 30 min in a transparent plastic box. Mice were then injected with 10 μl hypertonic (2 or 10% NaCl, respectively, 607 and 3250 mOsm), hypotonic (deionized water, 17 mOsm) or isotonic (0.9% NaCl) solution administered intradermally on the dorsum of the hind paw using a 30-gauge needle connected to a 100 μl Hamilton syringe by PE-10 polyethylene tubing. The behavior of mice was observed and the time of licking and shacking of the paw (s) was recorded for a 5-min period starting immediately after the injection. For the experiments involving sensitization with PGE2, a local intraplantar injection of PGE2 (100 ng, 5 μl) was administrated 30 min prior to injection of the hyper- or hypotonic stimulus at the same injection site.

Carrageenan-induced inflammatory hyperalgesia

Carrageenan (5% in saline) was injected subcutaneously (20 μl) into the right hindpaw (Tonussi and Ferreira, 1992). Mice were submitted to von Frey filament application and tested for thermal sensitivity using immersion in a water bath at 46°C.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean±s.e.m. and analyzed by a Student's t-test in unpaired series to compare scores (raw data or AUC) between TREK-1−/− and TREK-1+/+ animals. In all cases, the significance level was P<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Table I

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the CNRS and the Institut Paul Hamel. We thank Martine Jodar, Gisèle Jarretou and Yvette Benhamou for expert technical assistance. We are very grateful to Dr Valerie Giordanengo for her help with semiquantitative PCR experiments, to Dr Lachlan Rash for all his comments on this paper and to Marc Zanzouri for helpful discussion.

References

- Alessandri-Haber N, Joseph E, Dina OA, Liedtke W, Levine JD (2005) TRPV4 mediates pain-related behavior induced by mild hypertonic stimuli in the presence of inflammatory mediator. Pain 118: 70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri-Haber N, Yeh JJ, Boyd AE, Parada CA, Chen X, Reichling DB, Levine JD (2003) Hypotonicity induces TRPV4-mediated nociception in rat. Neuron 39: 497–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearzatto B, Lesage F, Reyes R, Lazdunski M, Laduron P (2000) Axonal transport of TREK and TRAAK potassium channels in rat sciatic nerves. Neuroreport 11: 927–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Xie YK (1988) A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain 33: 87–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Alloui A, Monteil A, Barrere C, Couette B, Poirot O, Pages A, McRory J, Snutch TP, Eschalier A, Nargeot J (2005) Silencing of the Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel gene in sensory neurons demonstrates its major role in nociception. EMBO J 24: 315–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Rosen TA, Tominaga M, Brake AJ, Julius D (1999) A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature 398: 436–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D (1997) The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389: 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, Dekker LV, Sardini A, Parker PJ, McNaughton PA (1999) Specific involvement of PKC-epsilon in sensitization of the neuronal response to painful heat. Neuron 23: 617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemin J, Girard C, Duprat F, Lesage F, Romey G, Lazdunski M (2003) Mechanisms underlying excitatory effects of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors via inhibition of 2P domain K+ channels. EMBO J 22: 5403–5411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Vasko MR, Wu X, Staeva TP, Baez M, Zgombick JM, Nelson DL (1998) Multiple subtypes of serotonin receptors are expressed in rat sensory neurons in culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 287: 1119–1127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirjak G, Enyedi P (2002) TASK-3 dominates the background potassium conductance in rat adrenal glomerulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 16: 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew LJ, Wood JN, Cesare P (2002) Distinct mechanosensitive properties of capsaicin-sensitive and -insensitive sensory neurons. J Neurosci 22: RC228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Duprat F, Lesage F, Reyes R, Romey G, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M (1996) Cloning, functional expression and brain localisation of a novel unconventional outward rectifier K+ channel. EMBO J 15: 6854–6862 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioretti B, Catacuzzero L, Tata AM, Franciolini R (2004) Histamine activates a background arachidonic acid-sensitive K channel in embryonic chick dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurosciences 125: 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guler AD, Lee H, Iida T, Shimizu I, Tominaga M, Caterina M (2002) Heat-evoked activation of the ion channel, TRPV4. J Neurosci 22: 6408–6414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Guy N, Laigle C, Blondeau N, Mazzuca M, Lang-Lazdunski L, Widmann C, Zanzouri M, Romey G, Lazdunski M (2004) TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in neuroprotection and general anaesthesia. EMBO J 23: 2684–2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, Dony JG (1963) The inhibitory effect of fentanyl and other morphine-like analgesics on the warm water induced tail withdrawl reflex in rats. Arzneimittelforschung 13: 502–507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius D, Basbaum AI (2001) Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature 413: 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Choe C, Kim D (2005) Thermosensitivity of the two-pore domain K+ channels TREK-2 and TRAAK. J Physiol 564: 103–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Kim D (2006) TREK-2(K2P10.1) and TRESK (K2P18) are major background K+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili N, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Simone DA (2001) Influence of thermode size for detecting heat pain dysfunction in a capsaicin model of epidermal nerve fiber loss. Pain 91: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontinen VK, Kauppila T, Paananen S, Pertovaara A, Kalso E (1999) Behavioural measures of depression and anxiety in rats with spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathy. Pain 80: 341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Koltzenburg M, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO (1992) Responsiveness and functional attributes of electrically localized terminals of cutaneous C-fibers in vivo and in vitro. J Neurophysiol 68: 581–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Friedman JM (2003) Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4−/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13698–13703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Tobin DM, Bargmann CI, Friedman JM (2003) Mammalian TRPV4 (VR-OAC) directs behavioral responses to osmotic and mechanical stimuli in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 (Suppl 2): 14531–14536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret F, Lauritzen I, Patel AJ, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honoré E (2000) TREK-1 is a heat-activated background K+ channel. EMBO J 19: 2483–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret F, Patel AJ, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honoré E (1999) Mechano- or acid stimulation, two interactive modes of activation of the TREK-1 potassium channel. J Biol Chem 274: 26691–26696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey EW, Gold MS (1999) Ion channels of nociception. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 835–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst AD, Rennie G, Chapman CG, Meadows H, Duckworth MD, Kelsell RE, Gloger II, Pangalos MN (2001) Distribution analysis of human two pore domain potassium channels in tissues of the central nervous system and periphery. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 86: 101–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Iida T, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Tominaga T, Narumiya S, Tominaga M (2005) Sensitization of TRPV1 by EP1 and IP reveals peripheral nociceptive mechanism of prostaglandins. Mol Pain 1: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murbatian J, Lei Q, Sando JJ, Bayliss DA (2005) Sequential phosphorylation mediates receptor- and kinase-induced inhibition of TREK-1 background potassium channels. J Biol Chem 280: 30175–30184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CW, Porreca F, Cowan A (1988) Methodological refinements to the mouse paw formalin test. An animal model of tonic pain. J Pharmacol Methods 20: 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Watanabe H, Vriens J (2003) The TrpV4 channel: structure–function relationship and promiscuous gating behaviour. Pflügers Arch—Eur J Physiol 446: 298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AJ, Honoré E, Maingret F, Lesage F, Fink M, Duprat F, Lazdunski M (1998) A mammalian two pore domain mechano-gated S-type K+ channel. EMBO J 17: 4283–4290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honoré E (2001) Lipid and mechano-gated 2P domain K+ channels. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13: 422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott ED, Julius D (2003) A modular PIP2 binding site as a determinant of capsaicin receptor sensitivity. Science 300: 1284–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LO, Selitto JJ (1957) A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed tissue. Arch Int Pharmacodyn 61: 409–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW (1986) Sensory receptors in mammalian skin in an in vitro preparation. Neurosci Lett 66: 141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Flonta M (2001) Cold transduction by inhibition of a background potassium conductance in rat primary sensory neurones. Neurosci Lett 297: 171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund E, Cadmus R, Lu G (1957) A method for evaluating both non-narcotic and narcotic analgesics. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 95: 729–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szolcsanyi J, Anton F, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO (1988) Selective excitation by capsaicin of mechano-heat sensitive nociceptors in rat skin. Brain Res 446: 262–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal M, Bennett GJ (1994) Neuropathic pain sensations are differentially sensitive to dextrorphan. Neuroreport 21: 1438–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Solorzano G, Lei Q, Kim D, Bayliss DA (2001) Cns distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J Neurosci 21: 7491–7505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D (1998) The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 21: 531–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonussi CR, Ferreira SH (1992) Rat knee-joint carrageenin incapacitation test: an objective screen for central and peripheral analgesics. Pain 48: 421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F, de la Pena E, Belmonte C (2002) Specificity of cold thermotransduction is determined by differential ionic channel expression. Nat Neurosci 5: 254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Droogmans G, Wissenbach U, Janssens A, Flockerzi V, Nilius B (2004) The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature 430: 748–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JN, Boorman JP, Okuse K, Baker MD (2004) Voltage-gated sodium channels and pain pathways. J Neurobiol 61: 55–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodbury CJ, Zwick M, Wang S, Lawson JJ, Caterina MJ, Koltzenburg M, Albers KM, Koerber HR, Davis BM (2004) Nociceptors lacking TrpV1 and TrpV2 have normal heat responses. J Neurosci 24: 6410–6415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ (1999) Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet 353: 1959–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Table I