Abstract

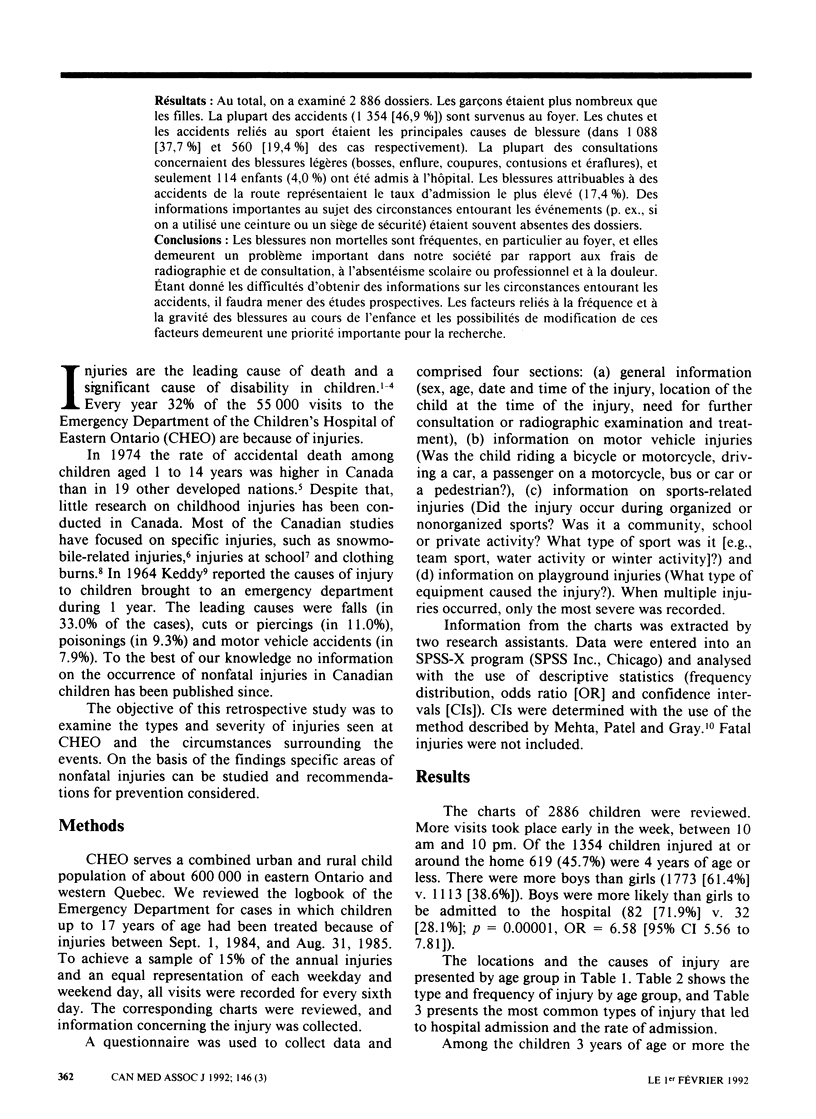

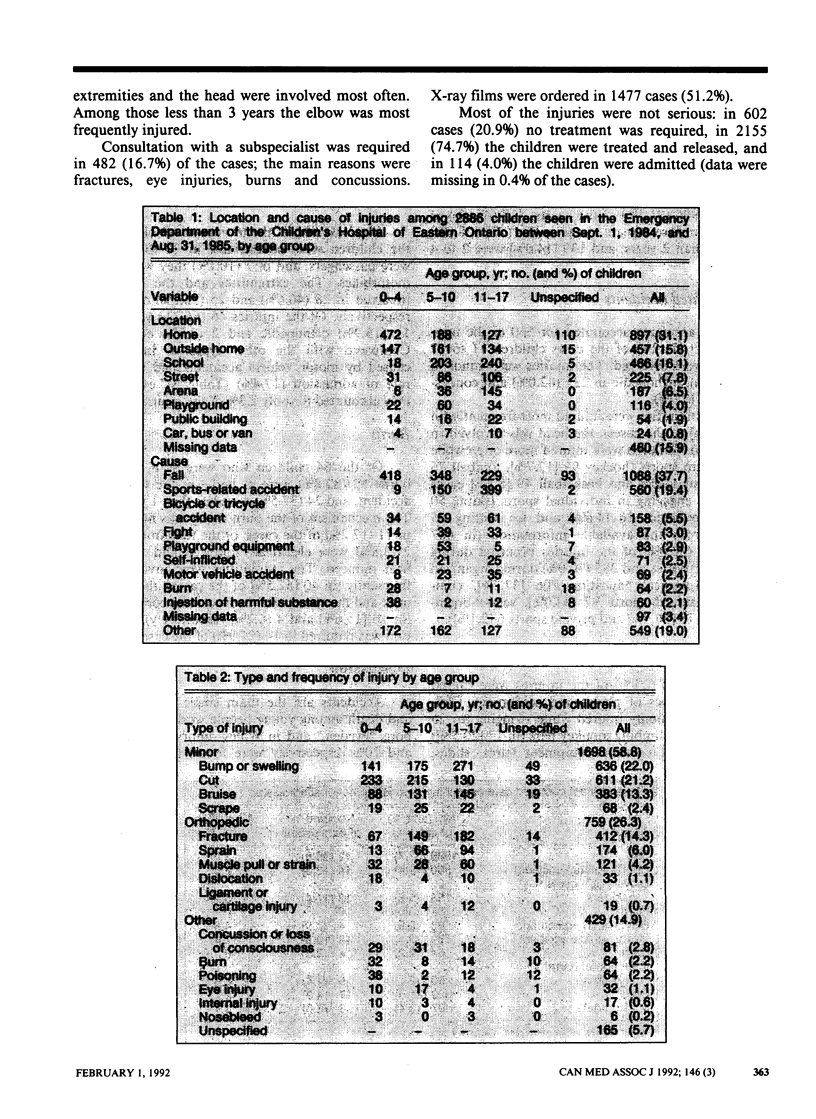

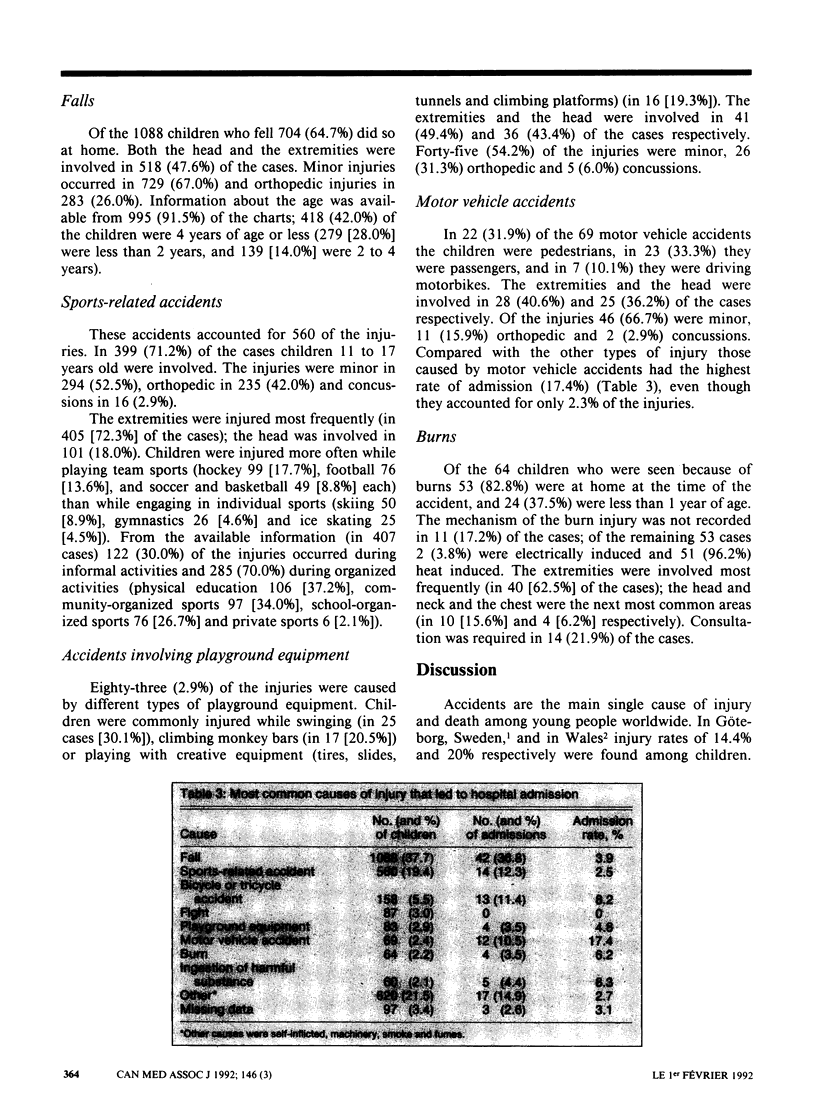

OBJECTIVE: To examine the types and severity of injuries seen in the Emergency Department of the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the circumstances surrounding the events. DESIGN: Chart review. SETTING: A tertiary care hospital that serves a child population of 600,000 in eastern Ontario and western Quebec. PARTICIPANTS: Every sixth day's charts of children up to 17 years of age who visited the Emergency Department because of injuries between Sept. 1, 1984, and Aug. 31, 1985, were examined retrospectively. RESULTS: A total of 2886 charts were reviewed. There were more boys than girls. Most (1354 [46.9%]) of the accidents had occurred at home. Falls and sports-related accidents were the leading causes of injury (in 1088 [37.7%] and 560 [19.4%] of the cases respectively). Most of the visits were for minor injuries (bumps, swellings, cuts, bruises and scrapes), and only 114 (4.0%) of the children were admitted to the hospital. Injuries from motor vehicle accidents accounted for the highest admission rate (17.4%). Important information regarding the circumstances surrounding the events (e.g., whether a seat belt or car seat was used) was frequently missing from the charts. CONCLUSIONS: Nonfatal injuries are common, especially in or around the home, and remain a significant problem in our society in terms of radiographic and consulting fees, time off from school or work and pain. Given the difficulties in obtaining information on the circumstances surrounding the events prospective studies are needed. Factors related to the occurrence and severity of childhood injury and whether these factors can be altered remain a high priority for research.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Done A. K. Aspirin overdosage: incidence, diagnosis, and management. Pediatrics. 1978 Nov;62(5 Pt 2 Suppl):890–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman W., Woodward C. A., Hodgson C., Harsanyi Z., Milner R., Feldman E. Prospective study of school injuries: incidence, types, related factors and initial management. Can Med Assoc J. 1983 Dec 15;129(12):1279–1283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. S., Finison K., Guyer B., Goodenough S. The incidence of injuries among 87,000 Massachusetts children and adolescents: results of the 1980-81 Statewide Childhood Injury Prevention Program Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 1984 Dec;74(12):1340–1347. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.12.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy C. R., Dhir A., Cameron B., Jones H., Fitzgerald G. W. Snowmobile injuries in northern Newfoundland and Labrador: an 18-year review. J Trauma. 1988 Aug;28(8):1232–1237. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198808000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEDDY J. A. ACCIDENTS IN CHILDHOOD: A REPORT ON 17,141 ACCIDENTS. Can Med Assoc J. 1964 Sep 26;91:675–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B., Sein C., McCarthy P. L. Safety education in a pediatric primary care setting. Pediatrics. 1987 May;79(5):818–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B., Chait A., Wootton I. D., Oakley C. M., Krikler D. M., Sigurdsson G., February A., Maurer B., Birkhead J. Frequency of risk factors for ischaemic heart-disease in a healthy British population. With particular reference to serum-lipoprotein levels. Lancet. 1974 Feb 2;1(7849):141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin E., Clarke N., Stahl K., Crawford J. D. One pediatric burn unit's experience with sleepwear-related injuries. Pediatrics. 1977 Oct;60(4):405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan D. Childhood injuries in India: extent of the problem and strategies for control. Indian J Pediatr. 1986 Sep-Oct;53(5):607–615. doi: 10.1007/BF02748664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathorst Westfelt J. A. Environmental factors in childhood accidents. A prospective study in Göteborg, Sweden. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1982;291:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibert J. R., Maddocks G. B., Brown B. M. Childhood accidents--an endemic of epidemic proportion. Arch Dis Child. 1981 Mar;56(3):225–227. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanwick R. S. Clothing burns in Canadian children. Can Med Assoc J. 1985 May 15;132(10):1143–1149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. F., Wells J. K. The Tennessee child restraint law in its third year. Am J Public Health. 1981 Feb;71(2):163–165. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf A., Lewander W., Filippone G., Lovejoy F. Prevention of childhood poisoning: efficacy of an educational program carried out in an emergency clinic. Pediatrics. 1987 Sep;80(3):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]