Abstract

Cationic antimicrobial peptides are believed to exert their primary activities on anionic bacterial cell membranes; however, this model does not adequately account for several important structure-activity relationships. These relationships are likely to be influenced by the bacterial response to peptide challenge. In order to characterize the genomic aspect of this response, transcription profiles were examined for Escherichia coli isolates treated with sublethal and lethal concentrations of the cationic antimicrobial peptide cecropin A. Transcript levels for 26 genes changed significantly following treatment with sublethal peptide concentrations, and half of the transcripts corresponded to protein products with unknown function. The pattern of response is distinct from that following treatment with lethal concentrations and is also distinct from the bacterial response to nutritional, thermal, osmotic, or oxidative stress. These results demonstrate that cecropin A induces a genomic response in E. coli apart from any lethal effects on the membrane and suggest that a complete understanding of its mechanism of action may require a detailed examination of this response.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides are ubiquitous components of host defense mechanisms in multicellular organisms (2, 6, 8, 29). In most cases, peptide sequences are unique to each species or even to a single tissue within a species. Consequently, in nature there exists tremendous sequence diversity among active peptides. This diversity confounds efforts to identify common properties that would lead to detailed insight into their mechanisms of action or into the basis of their selective actions against microorganisms.

It is widely believed that the cationic nature of antimicrobial peptides promotes their association with anionic bacterial cell membranes and that the association with the membrane is followed by various types of membrane-invasive activities (29). Antimicrobial peptides clearly have an affinity for membranes and exert an array of membrane-invasive activities, including folding-insertion reactions (19), channel formation (4), pore formation (21), and complete structural disruption (18). However, there are virtually no reliable data indicating that anionic lipids are present on the extracellular surface of the bacterial cell membrane, and several important structure-activity relationships are not adequately explained by this mechanism. Examples of inadequately explained structure-activity relationships include the following. (i) Single amino acid substitutions entailing no net change in overall charge can dramatically alter the activities of antimicrobial peptides against one bacterial species but have little effect on their activities against another bacterial species (9). (ii) Cecropin A is not active against Staphylococcus aureus and it is not hemolytic, whereas melittin is bactericidal against S. aureus and potently hemolytic. Cecropin A-melittin hybrids that are isoelectric with wild-type cecropin A, however, are active against S. aureus, yet they remain nonhemolytic (3, 9, 25, 26). (iii) Cecropin A associates much more avidly with anionic membranes than with neutral membranes, but it is just as effective at creating ion channels in neutral membranes (20, 21). (iv) For some classes of peptides, systematic studies of their abilities to depolarize bacterial membranes illustrate a striking lack of correlation of their depolarization abilities with their antibacterial activities (27, 28).

Thus, antimicrobial peptides exhibit a specificity of interaction that cannot be explained by electrostatic charge and a mechanism of action that cannot be explained solely by membrane invasion. These observations, among others, have prompted some to doubt whether the cytoplasmic membrane is the most important target site of action for cationic antimicrobial peptides (27, 28). Transcript profiling by use of microarray technology enables us to examine the response of the bacterial genome to antimicrobial peptide treatment for clues to the mechanism of action of the peptide and for evidence that alternative targets exist. If other targets exist, one would expect peptides to evoke some degree of cellular response even if they were present at sublethal concentrations. Therefore, we hypothesized that antimicrobial peptides would cause selective and consistent alterations in the bacterial gene transcript profile at sublethal concentrations. Such alterations would imply that the peptide interacts directly or indirectly with regulatory mechanisms, and these interactions may affect the susceptibilities of bacteria to its antimicrobial action. We chose to study cecropin A because it is linear, naturally occurring, and among the most thoroughly studied antimicrobial peptides (7, 10, 22, 23). It has potent activity against Escherichia coli, resistance has not been observed to develop in susceptible strains, and whole-genome microarrays are commercially available.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial culture and survival assay.

E. coli K-12 MG1655 (17) was inoculated into 50 ml of Luria-Bertani broth and grown at 37°C with shaking to an optical density at 620 nm of 0.8 to 0.9. Bacteria were harvested via centrifugation and resuspended in the same volume of 30 mM 3n-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid-150 mM NaCl at pH 7.0 (isolation buffer). Ninety microliters of this suspension was placed into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Cecropin A was prepared as a stock solution of 10 mg/ml in water and diluted so that when 10-μl aliquots from each well were mixed with 90 μl of the bacterial suspension the final concentrations ranged from 0.3 to 10 μg/ml. Bacterial survival was assayed after 10 min by counting of colonies from serial dilutions that had been plated on Luria-Bertani agar plates after overnight incubation at 30°C.

RNA isolation.

Aliquots (18 ml) of bacteria in isolation buffer and 2 ml of cecropin A at 2.5 or 50 μM in water were mixed with shaking in small flasks and incubated at 38°C. After 10 min, 10 ml of the treated bacterial culture was added to 2 ml of lysis buffer, composed of 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) with 10 mM EDTA and 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate. This mixture was placed in a boiling water bath for 2 min, cooled for 3 min, and added to 1 ml of 2 M sodium acetate and 10 ml of phenol. After 5 min of vigorous shaking, 10 ml of chloroform was added and the mixture was shaken for another 10 min. This solution was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min, and the top layer (∼10 ml) was removed. The RNA was precipitated with ethanol-sodium acetate overnight at −70°C and centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was resuspended in RNALater (Ambion) and transferred into 2-ml Eppendorf tubes. TRIzol reagent (1.5 ml; Gibco BRL) was added, and the solution was incubated at 37.5°C for 10 min. Chloroform (0.3 ml) was then added, and the solution was incubated for another 10 min at 37.5°C. This solution was centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was removed and added to 0.75 ml of cold isopropanol in 2-ml Eppendorf tubes, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was removed, and the RNA pellet was washed twice with cold 70% ethanol and resuspended in 50 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. The amount of RNA in a small portion of this sample was measured by determining the absorbance at 260 nm. Samples of the RNA were separated by electrophoresis in agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide so that the 16S and 23S ribosomal bands could be used as indicators of RNA purity and integrity. rRNA was then removed by using RNA primers and a protocol supplied by Affymetrix Corporation Inc. (Santa Clara, Calif.).

Biotin labeling, fragmentation, hybridization of the enriched mRNA onto Affymetrix E. coli genome arrays, and fluorescent tagging with streptavidin-phycoerythrin were also done by the protocols supplied by Affymetrix.

Data analysis.

Chips were analyzed with a GeneArray scanner, GeneChip Fluidics Station 400, and GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640, all of which were from Affymetrix. Data were processed by using Microarray Suite, version 5.0 (MAS5), also from Affymetrix. GeneChip expression arrays are composed of 11 to 20 pairs of specific and unique 25-mer oligonucleotide probes. Hybridization specificity controls, consisting of oligonucleotides with single base substitutions, are included in the array. The combination of cDNA oligonucleotides with a perfect match and a single base pair mismatch is termed a probe set.

The mean signal intensity for all probe sets on each chip was calculated, and the signal intensities on each chip were normalized by applying a scale factor that adjusts the mean signal intensity on each chip to a common arbitrary value. Hybridization quality was judged by using 76 internal negative control genes and the uniformity of the overall signal. All negative controls were uniformly judged to be absent by the criteria applied in Affymetrix MAS5 microarray analysis software. A set consisting of one untreated sample, one sample treated with a sublethal concentration, and one sample treated with a lethal concentration was processed on each of 5 separate days. Among the five untreated samples, 17 to 35% of the 4,347 total genes were judged to be present by analysis with MAS5 software, while the presence of 3 to 5% of the genes was judged to be marginal (the remainder were designated absent). The number of genes judged to be present in each sample treated with a sublethal concentration was within 1 to 3% of that judged to be present in the untreated sample processed on the same day. The number of genes judged to be present in the samples treated with a lethal concentration was more variable. One of the samples treated with a lethal concentration yielded only 3% of the genes judged to be present and was not analyzed further. The number of genes judged to be present in each of the four remaining samples treated with a lethal concentration was within 4 to 14% of that judged to be present in the untreated sample processed on the same day.

Significant changes in expression were identified by two different statistical tests. The first test involved the simple calculation of the mean signal intensities for each set of samples (untreated samples, samples treated with a sublethal concentration, and samples treated with a lethal concentration) and application of a two-tailed Student's t test to evaluate the differences between the means.

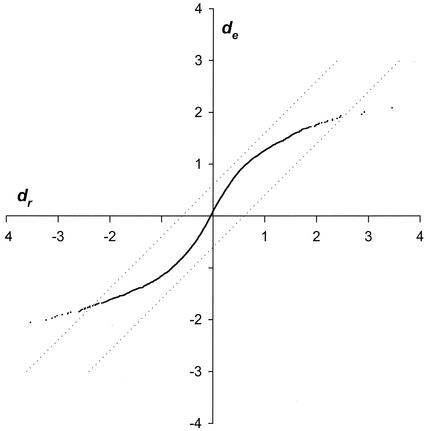

The second test closely followed the statistical assessment of microarrays (SAM) method of Tusher et al. (24). SAM analysis tends to be conservative because it assigns the greatest uncertainty to the greatest change, even if the uncertainty arises from different genes. The five untreated samples and the five samples treated with a sublethal concentration, each taken four at a time, yielded 25 different combinations or experiments in which four untreated samples and four samples treated with a sublethal concentration were compared. The mean signal intensities for the treated and untreated samples [x̄U(i) and x̄T(i), respectively], the standard deviation for the set of eight measurements [σ(i)], and relative differences {dr(i) = [x̄U(i) − x̄T(i)/σ(i)]} were calculated for each gene i in each experiment. An average relative difference for each gene [r(i)] was determined for the 25 experiments, and the results were sorted such that r(j) represented the jth largest relative difference.

Control experiments were created by calculating the mean intensity for two untreated samples and two treated samples [x̄A(i)] and for two of the remaining untreated samples and two of the remaining treated samples [x̄B(i)] and calculating an expected difference {de(i) = [x̄A(i) − x̄B(i)/σ(i)]} for each gene. Given five untreated and five treated samples, it is possible to create 900 different control experiments of this type. These control experiments were generated by means of a computer program, and the expected differences for each gene were sorted so that de(j) represented the jth largest expected difference. Finally, an average expected difference [e(j)] was calculated for all 900 control experiments. A critical difference [dc(j) = r(j) − e(j)] was calculated for each gene, and genes for which expression levels changed significantly were identified by setting threshold values (Δ+ and Δ−) and finding genes for which c was <Δ− or c was >Δ+. Genes for which de(j) − e(j) was <Δ− or de(j) − e(j) was >Δ+ in any single control experiment were deemed false discoveries. The false discovery rate for a given value of Δ was the number of false discoveries for this threshold, averaged over all the control experiments, divided by the number of genes for which |c| was >Δ. An analysis comparing untreated samples and samples treated with a lethal concentration was performed in a similar manner, except that the availability of data from only four samples treated with a lethal concentration yielded 180 control experiments.

RESULTS

Bactericidal activity of cecropin A.

In previous studies (21), E. coli ML-35p exhibited rates of survival of 50 and 10% following 10-min incubations in 3.6 and 6.8 μg of cecropin A per ml, respectively, while 50% of isolates of a K1 strain of E. coli survived a 10-min incubation with 6.8 μg of cecropin A per ml and 50% of isolates of a K-12 strain survived a 10-min incubation with 2.8 μg of cecropin A per ml (20). With respect to 10-min treatments, the present data indicate that 0.25 μg/ml is the highest concentration at which no bactericidal activity is observed, whereas 5 μg/ml is the lowest concentration at which <1% of the bacteria survive. On the basis of these results, the former concentration was used for treatments with a sublethal concentration, and the latter was used for treatments with a lethal concentration.

Treatment with a sublethal concentration.

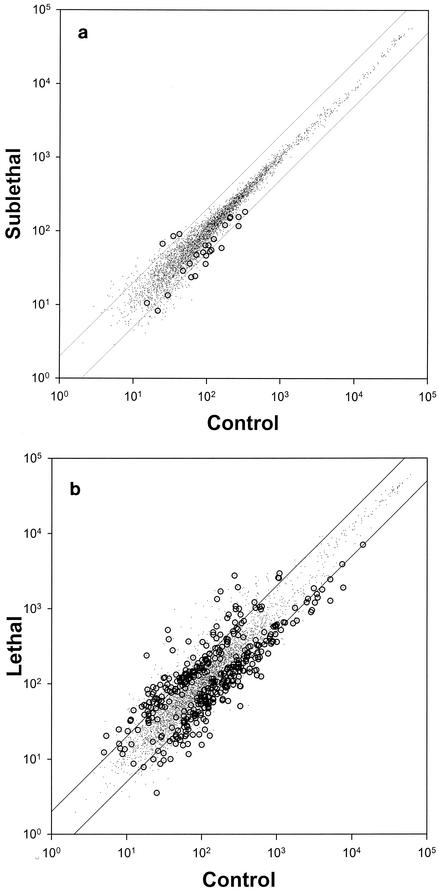

t-test analysis (P < 0.05) of the transcript profile data for untreated bacterial cultures and bacterial cultures treated with a lethal concentration indicated that the transcript levels increased for 5 genes and decreased for 31 genes in response to treatment. SAM analysis of genes with a c value <0 and a Δ value equal to −0.5 yielded 33 genes, but with a false discovery rate of 42%. Therefore, we set Δ equal to −0.6, for which the yield was 23 genes and the false discovery rate was <1%. SAM analysis of genes with a c value >0 and a Δ value equal to 0.5 yielded six genes, with a false discovery rate of >200%, but at Δ equal to 0.6, the analysis yielded three genes and the false discovery rate dropped to <1%. Thus, SAM analysis with thresholds of ±0.6 suggests that treatment with cecropin A at a sublethal concentration causes a significant change in the transcript levels for 26 genes (Table 1, Fig. 1a and 2). All 26 genes identified by SAM analysis were among the 36 genes for which P was <0.05 by the t test. By the criteria applied in Affymetrix MAS5 software, all 23 upregulated gene messages were designated present for the untreated samples and all 3 upregulated gene messages were designated present for the treated samples.

TABLE 1.

Genes with significantly altered transcript levels following sublethal treatment a

| Gene | Wisconsin functional group | SL v C | P (SL v C) | L v C | P (L v C) | dr | dc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yacH (b0117) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.62 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| mbhA (b0230) | Cell processes (including adaptation, protection) | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 3.0 | 1.1 |

| yaiL (b0354) | DNA replication, recombination, modification and repair | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| acrB (b0462) | Cell processes (including adaptation, protection) | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| ylcD (b0574) | Putative transport proteins | 0.61 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.82 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| entE (b0594) | Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| ybfC (b0704) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| rh1E (b0797) | Transcription, RNA processing, and degradation | 2.69 | 0.01 | 2.58 | 0.10 | −3.5 | −1.4 |

| ybiA (b0798) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 2.9 | 1.0 |

| ybiX (b0804) | Putative enzymes | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| — (b0817) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| — (b0872) | Energy metabolism | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| csgD (b1040) | Cell structure | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| pin (b1158) | Phage, transposon, or plasmid | 0.74 | 0.03 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| ychK (b1234) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| — (b1364) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.30 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| ydbA 1(b1401) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.35 | 0.05 | 1.08 | 0.88 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| ydcF (b1414) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| fdnH (b1475) | Energy metabolism | 0.57 | 0.00 | 3.16 | 0.36 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

| ynhA (b1679) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| — (b1973) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| hisC (b2021) | Amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism | 2.15 | 0.02 | 1.51 | 0.54 | −2.9 | −0.9 |

| hisH (b2023) | Amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism | 2.43 | 0.01 | 2.80 | 0.04 | −2.9 | −0.9 |

| yiaT (b3584) | Cell structure | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| yjbO (b4050) | Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 0.67 | 0.02 | 2.11 | 0.21 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| iadA (b4328) | Translation, posttranslational modification | 0.61 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

SL v C, ratio of transcript level following treatment with a sublethal concentration relative to the level for control samples; P value, value of Student's two-tailed t statistic for the treated samples versus the control samples; L v C, ratio of transcript level following treatment with a lethal concentration relative to the level for control samples; dr and de are as defined in Materials and Methods and are applied to the samples treated with a sublethal concentration and control samples. Only results with dc a value of ≥0.6 or dc a value of ≤−0.6 are included here.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of transcript levels (arbitrary luminescence units). Small dots, all genes; circled dots, genes with significantly changed transcript levels according to SAM analysis. The parallel lines enclose a region in which changes are less than twofold in either direction. (a) Untreated samples versus samples treated with a sublethal concentration; (b) untreated samples versus samples treated with a lethal concentration.

FIG. 2.

Results of SAM analysis applied to samples treated with a sublethal concentration and control samples. Lines are drawn at dc equal to ±0.6 to indicate the thresholds.

Among the 26 gene transcripts identified by SAM analysis, 11 (42%) corresponded to open reading frames with hypothetical protein products of unknown function, and 2 others (8%) corresponded to reading frames for which an imputed function has been assigned according to its sequence homology. Genome-wide, 37% of the open reading frames in E. coli are hypothetical products of unknown function, and 12% have only an imputed function. None of the 26 genes appear on the lists of 425 genes previously reported to be altered by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (17), heat shock (17), acetate (1), salicylate (15), or superoxide (15) stress. The random likelihood of finding 26 genes not on these lists among the ∼4,400 total genes is approximately 8%.

Several of these hypothetical gene products (e.g., yacH, ychK, yiaT, and b1364) have long hydrophobic segments and are thus likely to be membrane proteins. Two genes (rhlE and ybiA) are adjacent on the chromosome but are separated by 231 bases and are transcribed in opposite directions. All but three of the genes with altered transcript levels are moderately or highly conserved across multiple bacterial species. The three genes with no known sequence homology in other species (yacH, ybfC, and b1364) are all open reading frames with hypothetical products of unknown function.

Two genes (hisC and hisH) are components of the histidine biosynthesis pathway and are among the affected genes that are highly conserved among bacterial species. Together with rhlE (RNA helicase), they are the only three genes whose transcript levels are increased in bacteria treated with sublethal concentrations.

Independent of statistical significance tests, we noted increases and decreases in the levels of expression of several gene clusters. For example, the levels of expression of other genes in the his cluster (hisDBAF) were increased between 1.07- and 1.87-fold. The levels of expression of gene transcripts from the yhf cluster (yhfLMNQR) were elevated between 1.03- and 2.43-fold, with only one exception (yhfP, whose level of expression was decreased 1.3-fold). The levels of expression of genes from the nar cluster (narWYZU) were elevated between 1.10- and 1.70-fold, with one exception (narV, whose level of expression was decreased 1.14-fold). The levels of expression of genes from the lac operon (lacAYZI) were uniformly elevated between 1.35- and 2.45-fold. The levels of expression of gene transcripts from the ydd cluster (yddABC) were elevated between 1.02- and 1.66-fold, while the levels of expression of those from unnamed clusters of seven genes ahead of ydd (b1483 to b1489) and nine genes following ydd (b1498 to b1506) were broadly decreased up to 3.6-fold. Several other such clusters may be identified, and in most cases these correspond to genes whose functions are unknown. While the magnitudes of the transcript level changes for these clusters are not large, the presence of these clusters suggests that they are induced responses to peptide treatment rather than random fluctuations in the data.

Treatment with a lethal concentration.

t-test analysis of transcript profile data for untreated bacterial cultures and bacterial cultures treated with a lethal concentration with P values <0.05 indicated that the transcript levels increased for 70 genes and decreased for 128 genes in response to treatment. SAM analysis of genes with a c value of <0 and a Δ value of −0.4 yielded 238 genes, with a false discovery rate of <1%. SAM analysis of genes with a c value of >0 and a Δ value of 0.4 yielded 178 genes, with a false discovery rate of 3%. Only 161 of the 416 genes exceeding these thresholds according to SAM analysis had a P value <0.05 by the t test. Thus, SAM analysis with threshold of ±0.4 (Fig. 1b) is less conservative than the t test when SAM analysis is applied to a comparison of untreated samples and samples treated with a lethal concentration. This implies that the differences in levels of expression were large relative to the overall variance in the data set. The changes in transcript levels resulting from treatment with a lethal concentration did not parallel the changes resulting from treatment with a sublethal concentration. Indeed, in most cases treatment with a lethal concentration tended to reverse the changes induced by treatment with a sublethal concentration (Table 1).

Transcript levels from genes in the phoPQ and sapABCDF operons, which are implicated in antimicrobial peptide resistance in Salmonella, are unchanged after treatment with a sublethal or a lethal concentration (5). Transcript levels for grpE, recA, katG, inaA, and fabA were unchanged in response to treatment with either a sublethal or a lethal concentration of cecropin A, in agreement with the findings of Oh et al. (12-14). Our results also agree with theirs in that we found that transcript levels for osmY increased 1.3-fold upon treatment with a lethal concentration. This increase, however, did not meet the criteria for significance by the t test (P = 0.70) or SAM analysis (c = 0.2), and expression levels were unchanged upon treatment with a sublethal concentration. The previous studies used an intermediate concentration of peptide (0.4 μM) and a different strain of E. coli, so that precise comparisons are not possible. Furthermore, Oh et al. (12-14) used a measure of transcriptional activity, whereas the microarrays used in this work are a measure of transcript levels.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that cecropin A induces a nonlethal response with intracellular consequences in E. coli. This response takes the form of altered transcript levels for a distinct and rather small set of genes. Although the effects documented herein are nonlethal, they suggest that more extensive changes may occur at higher peptide concentrations. Such changes may regulate or even determine the susceptibility of the organism.

The chief pitfall that one must avoid with transcript profiling is that changes that appear to be significant may arise from random fluctuations in the large amount of data generated. To avoid this outcome, we have applied statistical procedures that help estimate an upper limit for the rate of false positivity. Close inspection of the data in Fig. 2 shows that the threshold levels determined by SAM analysis are positioned at natural breakpoints where the magnitude of relative differences outstrips the magnitude of expected differences. This and the many instances in which gene clusters appear to be upregulated or downregulated in concert support the validity of the results.

We have focused on the nonlethal effects of peptide action rather than the death response. At sublethal peptide concentrations, genes with increased or decreased transcript levels are not necessarily implicated in the antimicrobial mechanism of cecropin A, and the changes may even represent an adaptive response to peptide-induced stress. We observed nearly threefold reductions in the levels of several gene transcripts following treatment with a sublethal concentration, and these reductions evidently did not diminish the rate of bacterial survival. It remains possible, however, that the more complete shutdown of one or more of these genes may be lethal, or this degree of downregulation may be lethal under less artificial growth conditions.

Since E. coli can replicate with a generation time of 20 min, a 10-min exposure to peptide is relatively long in the life cycle of the organism. This exposure was the shortest that could be performed with multiple simultaneous samples. It is noteworthy, however, that treatment with lethal doses of peptide caused a significant change in only ∼10% of the 4,290 genes in the E. coli genome. This indicates that we succeeded in isolating transcripts before global shutdown of the genomic machinery or extensive degradation of RNA transcripts had occurred. It is also noteworthy that most genes regulated in one direction after treatment with a sublethal concentration were regulated in the opposite direction after treatment with a lethal concentration (Table 1). While we cannot explain this specific pattern, it constitutes evidence that the changes observed after treatment with a sublethal concentration did not merely represent the lethal response by a small number of bacteria.

Efforts to explain the mechanisms of action of antimicrobial peptides have focused on the physical consequences of their interactions with cell wall components and, specifically, with cell membranes. These consequences have included ion channel formation, aqueous pore formation, blebbing followed by osmotic rupture of the membrane, as well as generalized disruption of the membrane architecture. These are certainly real consequences of peptide action; at least in some cases, however, these consequences often do not account for the lethal activities of the antimicrobial peptides or for the remarkable specificities of their actions against bacteria. The data reported herein suggest that the antimicrobial mechanism of cecropin A may also involve effects on gene regulation.

There is precedent for an effect of sublethal concentrations of antimicrobial peptides on intracellular protein concentrations, in that bactericidal membrane permeability-increasing protein and polymyxin B at sublethal concentrations both alter the concentrations of several proteins in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (16). Intracellular effects imply that cecropin A has penetrated the outer membrane and cell wall at sublethal concentrations and that it has reached the inner cell membrane. Since it is unlikely that the peptide passed through outer membrane porins, this also suggests that cecropin A can penetrate the outer bacterial membrane without a measurable adverse effect on survival. Thus, it may also penetrate the inner cell membrane and reach intracellular targets without a measurable adverse effect on survival.

Cecropin A might affect gene transcript levels in several ways. One is direct action on a cellular target. Other than the lipid membrane or structural components of the cell wall, however, no targets have been identified for any of the hundreds of cationic antimicrobial peptides. Moreover, it seems unlikely that antimicrobial peptides specifically bind to protein receptors because they exhibit broad sequence diversity and because all-d and all-l forms appear to have equal potencies (26). A second way in which cecropin A might alter transcript levels is through some form of nonlethal physical perturbation of the cell membrane. Clear instances of increased membrane permeability caused by the peptide at sublethal concentrations have been described (27, 28). In this case, the altered transcriptional profile might represent a reaction to the stress of increased permeability. However, the transcript profile of E. coli treated with cecropin A does not overlap its profile under conditions of nutritional, thermal, osmotic, or oxidative stress (1, 12-15, 17). Moreover, this explanation for altered transcript levels does not help explain the specificity of antimicrobial peptide action.

A third way in which cecropin A might alter transcript levels is by interfering with normal interactions between membrane lipids and membrane-bound proteins. Diffusible membrane-bound cations are a distinctly foreign chemical entity in a bacterial membrane, and their positive charge may be the basis for semispecific interactions with negatively charged membrane proteins. For example, altered gene expression may result from interference with membrane-bound sensory components of two-component signaling systems. Conversely, the inherent resistance of some organisms to peptide action may be due to the absence of sensitive two-component signaling systems. This has precedent in Streptococcus pneumoniae, in which the lethal action of vancomycin involves a membrane-bound sensory protein and signal transduction pathways (11).

In summary, the data presented here illustrate the complexities of the bacterial response to antimicrobial peptides that are not generally considered when investigators attempt to understand their mechanisms of action. It is prudent to distinguish between the site of peptide action and the mechanism of its action. The lethality of the antimicrobial mechanism may be strongly influenced by the adaptive or maladaptive nature of the bacterial response. Consequently, the ability of a peptide to induce a response (as demonstrated herein) may be an important aspect of its antimicrobial mechanism and may determine its spectrum of activity. Thus, the search for antimicrobial peptide targets should be broadened beyond lipids of the cell membrane to include other cell components both within and outside of the membrane. Additional studies of the effects of antimicrobial peptides on gene expression are clearly warranted and should focus on the effects of other peptides on transcript levels and on the adaptive or maladaptive role of genes whose transcript levels are altered by peptide action.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Affymetrix for providing E. coli GeneChip microarrays; Lewis Chodosh, Elizabeth Keiper, and Kate Dugan for microarray hybridization and processing; Don Baldwin and Katherine Li for assistance in data processing; Michael Sebert for critical reading of the manuscript; and Ponzy Lu for advice and encouragement.

We thank the Roy and Diana Vagelos Scholars Program in the Molecular Life Sciences for financial support of R.W.H. J.N.W. is supported by NIH grants AI38436 and AI44231. P.H.A. is supported by NIH grants GM54617 and AI43412 and the American Heart Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, C. N., J. McElhanon, A. Lee, R. Leonhart, and D. A. Siegele. 2001. Global analysis of Escherichia coli gene expression during the acetate-induced acid tolerance response. J. Bacteriol. 183:2178-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boman, H. G. 1995. Peptide antibiotics and their role in innate immunity. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 13:61-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boman, H. G., D. Wade, I. A. Boman, B. Wahlin, and R. B. Merrifield. 1989. Antibacterial and antimalarial properties of peptides that are cecropin-melittin hybrids. FEBS Lett. 259:103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen, B., J. Fink, R. B. Merrifield, and D. Mauzerall. 1988. Channel-forming properties of cecropins and related model compounds incorporated into planar lipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:5072-5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groisman, E. A., F. Heffron, and F. Solomon. 1992. Molecular genetic analysis of the Escherichia coli phoP locus. J. Bacteriol. 174:486-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock, R. E. W., and D. S. Chapple. 1999. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 43:1317-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hultmark, D., H. Steiner, T. Rasmuson, and H. G. Boman. 1980. Insect immunity. Purification and properties of three inducible bactericidal proteins from hemolymph of immunized pupae of Hyalophora cecropia. Eur. J. Biochem. 106:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehrer, R. I., T. Ganz, and M. E. Selsted. 1990. Defensins: natural peptide antibiotics from neutrophils. ASM News 56:315-318. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maloy, W. L., and U. P. Kari. 1995. Structure-activity studies on magainins and other host defense peptides. Biopolymers 37:105-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrifield, R. B., L. D. Vizioli, and H. G. Boman. 1982. Synthesis of the antibacterial peptide cecropin A(1-33). Biochemistry 21:5020-5031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak, R., B. Henriques, E. Charpentier, S. Normark, and E. Tuomanen. 1999. Emergence of vancomycin tolerance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature 399:590-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh, J. T., Y. Cajal, P. S. Dhurjati, T. K. Van Dyk, and M. K. Jain. 1998. Cecropins induce the hyperosmotic stress response in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1415:235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh, J. T., Y. Cajal, E. M. Skowronska, S. Belkin, J. H. Chen, T. K. Van Dyk, M. Sasser, and M. K. Jain. 2000. Cationic peptide antimicrobials induce selective transcription of micF and osmY in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1463:43-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh, J. T., T. K. Van Dyk, Y. Cajal, P. S. Dhurjati, M. Sasser, and M. K. Jain. 1998. Osmotic stress in viable Escherichia coli as the basis for the antibiotic response by polymyxin B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 246:619-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pomposiello, P. J., M. H. J. Bennik, and B. Demple. 2001. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J. Bacteriol. 183:3890-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi, S. Y., Y. Li, A. Szyroki, I. G. Giles, A. Moir, and C. D. Oconnor. 1995. Salmonella-Typhimurium responses to a bactericidal protein from human neutrophils. Mol. Microbiol. 17:523-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richmond, C. S., J. D. Glasner, R. Mau, H. F. Jin, and F. R. Blattner. 1999. Genome-wide expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3821-3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shai, Y. 1999. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by alpha-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:55-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silvestro, L., and P. H. Axelsen. 2000. Membrane-induced folding of cecropin A. Biophys. J. 79:1465-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvestro, L., K. Gupta, J. N. Weiser, and P. H. Axelsen. 1997. The concentration-dependent membrane activity of cecropin A. Biochemistry 36:11452-11460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silvestro, L., J. N. Weiser, and P. H. Axelsen. 2000. Antibacterial and antimembrane activities of cecropin A in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 44:602-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner, H. 1982. Secondary structure of the cecropins: antibacterial peptides from the moth Hyalophora cecropia. FEBS Lett. 137:283-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner, H., D. Hultmark, Å. Engström, H. Bennich, and H. G. Boman. 1981. Sequence and specificity of two antibacterial proteins involved in insect immunity. Nature 292:246-248.7019715 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tusher, V. G., R. Tibshirani, and G. Chu. 2001. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5116-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade, D., D. Andreu, S. A. Mitchell, A. M. V. Silveira, A. Boman, H. G. Boman, and R. B. Merrifield. 1992. Antibacterial peptides designed as analogs or hybrids of cecropins and melittin. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 40:429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wade, D., A. Boman, B. Wåhlin, C. M. Drain, D. Andreu, H. G. Boman, and R. B. Merrifield. 1990. All-d amino acid-containing channel-forming antibiotic peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4761-4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, M. H., and R. E. W. Hancock. 1999. Interaction of the cyclic antimicrobial cationic peptide bactenecin with the outer and cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu, M. H., E. Maier, R. Benz, and R. E. W. Hancock. 1999. Mechanism of interaction of different classes of cationic antimicrobial peptides with planar bilayers and with the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 38:7235-7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]