Abstract

The bacterial DnaA protein binds to the chromosomal origin of replication to trigger a series of initiation reactions, which leads to the loading of DNA polymerase III. In Escherichia coli, once this polymerase initiates DNA synthesis, ATP bound to DnaA is efficiently hydrolyzed to yield the ADP-bound inactivated form. This negative regulation of DnaA, which occurs through interaction with the β-subunit sliding clamp configuration of the polymerase, functions in the temporal blocking of re-initiation. Here we show that the novel DnaA-related protein, Hda, from E.coli is essential for this regulatory inactivation of DnaA in vitro and in vivo. Our results indicate that the hda gene is required to prevent over-initiation of chromosomal replication and for cell viability. Hda belongs to the chaperone-like ATPase family, AAA+, as do DnaA and certain eukaryotic proteins essential for the initiation of DNA replication. We propose that the once-per-cell-cycle rule of replication depends on the timely interaction of AAA+ proteins that comprise the apparatus regulating the activity of the initiator of replication.

Keywords: AAA+ protein/cell cycle/DnaA/Escherichia coli/replication

Introduction

Chromosome replication is tightly regulated to ensure that the initiation reaction of replication takes place only once during the cell cycle (Diffley, 1996; Messer and Weigel, 1996). Part of the regulation involves the inactivation of the replication origin and the proteins required for initiation, at specific times once the process has begun. In eukaryotic cells, a major mechanism establishing this once-per-cell-cycle rule is termed ‘licensing’ (Blow and Laskey, 1988). It depends on the limited assembly of the pre-replication complex in late M or G1. That is because of the degradation of the Cdc6 protein during G1 (Donovan et al., 1997; Tanaka et al., 1997). The Cdc6 protein allows loading of the components of the pre-replication complex, termed MCM (mini-chromosome maintenance) proteins, onto the replication origins. At least in yeast, some MCM proteins are transported to the cytoplasm in S phase and that is also important for licensing (Tye, 1999).

In prokaryotes, the DnaA protein, widely conserved among bacterial species, plays a key role in the initiation process (Messer and Weigel, 1996). The Escherichia coli DnaA protein cooperatively binds to the chromosomal replication origin (oriC), opens the duplex, and guides entry of the DnaB helicase onto the single-stranded DNA. This unwound region is then expanded to allow the loading of primase and DNA polymerase (pol) III holoenzyme, also known as the chromosomal replicase (Messer and Weigel, 1996). The initial reaction in the loading of the replicase involves the formation of the so-called sliding clamp, which is made up of a ring-shaped dimer of the β-subunit (DnaN protein) of the pol III holoenzyme. After encircling the DNA strand, the clamp stabilizes the replicase to enable processive replication (Kelman and O’Donnell, 1995). These mechanisms initiating DNA replication are essentially the same in eukaryotic cells (Baker and Bell, 1998).

In E.coli, at least three systems for blocking multiple replication events have been found (Boye et al., 2000). First, immediately after initiation, oriC is temporarily inactivated by the SeqA protein (Lu et al., 1994; von Freiesleben et al., 1994). This protein preferentially binds to the hemimethylated form of the oriC that is produced by replication of the fully methylated form (Brendler and Austin, 1999). The hemimethylated state of oriC is maintained for only 10 min in cells dividing every 30 min. In experiments where the seqA gene is disrupted, re-initiation of the origin occurs at a significant rate (Lu et al., 1994; Boye et al., 1996). In Gram-positive bacteria, a Dam-like methylation system and a SeqA homolog are both absent, suggesting that this may not be a generalized mechanism among bacteria (Seror et al., 1994).

Secondly, DnaA titration on the datA locus of the chromosome prevents the occurrence of extra initiations (Kitagawa et al., 1996, 1998). Deletion of this locus, which contains a cluster of high affinity binding sites (9mer or DnaA box) for the DnaA protein, induces over-initiation at a level similar to that found following seqA deletion (Kitagawa et al., 1998). The level of free DnaA protein in the cytosol may be reduced by the datA locus so that DnaA molecules accessible to oriC are limited.

Thirdly, the DnaA protein is inactivated soon after initiation has occurred. This negative regulation of initiator function has been termed ‘the regulatory inactivation of DnaA (RIDA)’ (Katayama et al., 1998). The DnaA protein forms a stable complex with ATP or ADP, and only the ATP-bound form is active in initiation (Sekimizu et al., 1987). Studies using replication cycle-synchronized cultures suggest that the number of ATP–DnaA molecules increases prior to initiation, and that ATP–DnaA is converted to the inactive ADP form after initiation (Kurokawa et al., 1999). In the dnaAcos mutant, which is defective in RIDA, there are excessive rounds of initiation during the cell cycle, leading to inhibition of cell division and cell growth (Kellenberger-Gujer et al., 1978; Katayama, 1994; Katayama and Kornberg, 1994; Katayama and Crooke, 1995).

The timely inactivation of proteins involved in initiation of replication, which acts as a negative controlling system, appears to exist ubiquitously among prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. DnaA in prokaryotes and several factors involved in the initiation of replication in eukaryotes, such as the origin recognition complex (ORC), Cdc6 and MCM proteins, are classified into the same protein family, named AAA+ (Neuwald et al., 1999). The ATP-binding property of these AAA+ proteins is considered to have a regulatory role for their functions (Lee and Bell, 2000). The mechanism of RIDA in E.coli may be used as a model to predict how systems that employ AAA+ proteins to regulate the initiation of replication operate.

In RIDA, hydrolysis of DnaA-bound ATP yields the ADP-bound inactive form. This reaction is promoted in vitro by the β-subunit sliding clamp of the pol III holoenzyme (Katayama et al., 1998). As the β-subunit sliding clamp is formed upon loading of the replicase, DnaA becomes inactivated. This inactivation is directly linked to the initiation of replication, and coordinates switching from the initiator activity to the replication process. The interaction between the β-subunit and DnaA requires an unidentified factor tentatively named IdaB.

Here we show that a novel protein, Hda, mediates the interaction of DnaA with the β-subunit sliding clamp to promote hydrolysis of DnaA-bound ATP as well as the cellular fraction containing IdaB. Hda is essential for the control of initiation of DNA replication by inhibiting re-initiation of replication.

Results

Identification of the hda gene

We isolated E.coli mutants that were defective in the stable maintenance of a single-copy plasmid, mini-F, at 30°C to identify the factors essential for its replication and partition. From these mutants, we selected ones that did not form colonies at 42°C on non-selective medium. We then identified genes that were able to rescue the cell growth of these mutants at 42°C by transforming cells with an E.coli chromosome library constructed in the multicopy plasmid pACYC184.

Using this method, we identified many genes essential for chromosomal replication (dnaA, dnaB, etc.), segregation (genes for topoisomerases; gyrB, parC, parE) and some novel genes (data not shown). One of these genes is a putative E.coli gene, f248c (b2496). Sequence analysis showed that the f248c gene codes for a protein structurally related to DnaA (Figure 1A); we named the f248c gene hda (homologous to DnaA). The homology with DnaA is highest in the DnaA domain III region containing the ATP binding site. This region bears common motifs seen in the AAA+ protein superfamily to which both proteins belong (Figure 1B). The homology between DnaA and Hda in this region is significantly higher than with other proteins belonging to this superfamily (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Escherichia coli Hda is homologous to DnaA. (A) The homologous region between DnaA (467 amino acids) and Hda (248 amino acids) is shown. I, II, III and IV represent the domains of DnaA (Messer and Weigel, 1996). The amino acid positions are also shown. Identities and similarities (in parenthesis) between the two proteins are indicated by percent values. (B) The regions including AAA+ motifs in DnaA and Hda with identical and similar amino acids (+) are shown. Amino acids are designated by the single-letter code. The numbers indicate amino acid positions in each protein. Defined AAA+ motifs are also shown (Neuwald et al., 1999).

We further analyzed the temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant that was rescued by the wild-type hda (hda+) gene, and found that the mutant gene present in these cells was a novel allele of the dnaN gene (dnaN36), which codes for the pol III β-subunit. This indicated that the hda gene was its multicopy suppressor. Whereas the wild-type hda gene suppressed the dnaN36 mutation at 42°C and allowed growth, the wild-type dnaA gene inhibited growth of the mutant even at 30°C (data not shown). These results suggest that the Hda and DnaA proteins have opposite functions in spite of their structural homology.

Hda is essential for cell growth

The natural hda gene present on the bacterial chromosome was deleted and replaced with a CmR gene, in cells carrying the hda+ mini-F plasmid, as described in Materials and methods. Next, the resultant Δhda::CmR mutation was transferred by P1 phage-mediated transduction into a strain with or without the hda-complementing plasmid (Table I, Experiment A). Transduction of the Δhda::CmR mutation depended on the presence of the complementing plasmid, indicating that the hda gene was essential for cell growth.

Table I. Transduction of the Δhda::CmR mutation.

| Experiment | Recipient strain | Temperature (°C) | Transduction frequency (relative efficiency) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | C600/mini-F | 37 | 2.0 × 10–8 (1) |

| C600/mini-F-hda+ | 37 | 5.0 × 10–6 (250) | |

| B | C600 | 37 | 2.2 × 10–7 (1) |

| C600 ΔrnhA | 37 | 1.5 × 10–7 (0.7) | |

| C600 ΔrnhA dnaA::Km | 37 | 6.4 × 10–5 (290) | |

| C600 ΔrnhA dnaA::Tc | 37 | 4.2 × 10–5 (191) | |

| C600 rnhA::Ap | 37 | 0.9 × 10–7 (0.4) | |

| C600 rnhA::Ap dnaA::Tc | 37 | 4.3 × 10–5 (195) | |

| C600 rnhA::Ap dnaA(Ts) | 30 | 1.0 × 10–7 (0.5) | |

| 40 | 8.5 × 10–5 (386) | ||

| C600 ΔrnhA ΔoriC | 37 | 2.9 × 10–5 (193) | |

| C600 ΔrnhA ΔoriC dnaA::Km | 37 | 2.9 × 10–5 (193) |

Mini-F-hda+, pJK286-hda+; dnaA::Km and dnaA::Tc, dnaA insertion mutations constructed by Y.Sakakibara (unpublished data); rnhA::Ap, rnhA17::Tn3; ΔrnhA, rnhA deletion mutation constructed by J.Kato (unpublished data); ΔoriC, oriC del-1071::Tn10; dnaA (ts), dnaA167.

Hda is involved in replication from oriC

Based on the finding that Hda is homologous to DnaA, we asked whether Hda is involved in the initiation events of chromosomal replication. To clarify the function of Hda, we first analyzed genetically the interaction between the hda gene and the other genes involved in replication. In E.coli, lack of RNaseH, the rnhA gene product, provokes initiations at sites (oriK) other than oriC, which enables the chromosome to replicate in a manner independent of the dnaA gene and oriC (Kogoma, 1997). Therefore, if Hda is essential for initiation at oriC, disruption of the rnhA gene should rescue cell growth in the Δhda mutants as well as in the dnaA mutants. When the Δhda::CmR was transferred into a rnhA mutant by P1 transduction, the transduction frequency was as low as that with a control rnhA+ strain (Table I, Experiment B). These results indicate that the hda disruption is not suppressed by the rnhA mutation, and suggest that Hda plays a role other than that of the initiator.

Next, we examined the effects of the dnaA or oriC mutation on disruption of the hda gene. As described above, dnaA and oriC are essential for cell viability in a rnhA+ strain, but not in a rnhA– strain. The Δhda::CmR was transferred into the rnhA dnaA or rnhA oriC double mutants or the rnhA dnaA oriC triple mutant. As shown in Table I (Experiment B), colonies of tranductants were formed efficiently, in contrast to those of the rnhA single mutants. When an rnhA dnaAts mutant was used as a recipient, efficient transduction was seen only at the non-permissive temperature (Table I, Experiment B). These results indicate that the hda gene is dispensable for the viability of rnhA dnaA, rnhA oriC and rnhA dnaA oriC mutants. This suppression of the hda disruption, through depletion of the dnaA/oriC functions, correlates with the lack of dnaA-dependent replication from oriC. This suggests that Hda is involved in the replication from oriC. One explanation for the results is that the hda disruption leads to abnormal dnaA-dependent replication, such as over-initiation, from oriC. If lack of Hda leads to excessive initiation, then the hda disruption may be suppressed by the mutations inhibiting dnaA-dependent replication from oriC.

Hda is required for the regulation of DnaA protein by nucleotide binding

We then asked what role does Hda play in the initiation of replication from oriC? We noticed that the suppression of the hda disruptant resembled that of the dnaAcos mutant, which was deficient in RIDA. In this dnaAcos mutant, over-initiation from oriC occurs at the non-permissive temperature, but the oriC-deletion mutation suppresses this dnaA mutation (Katayama and Kornberg, 1994). Therefore, we speculated that Hda is involved in RIDA. The finding that the hda gene is a multicopy suppressor of the dnaN mutant adds strength to this hypothesis, because DnaN, which codes for the β-subunit of pol III, is an essential factor for RIDA (Katayama et al., 1998). To investigate this possibility further, we determined the in vivo levels of the nucleotide-bound DnaA forms using the hda-disrupted mutant cells. In randomly dividing cell cultures of wild-type strains, the ATP–DnaA level was only ∼20% of the total number of ATP/ADP–DnaA molecules (Kurokawa et al., 1999). Disruption of rnhA or both rnhA and oriC did not significantly affect this level (Kurokawa et al., 1999).

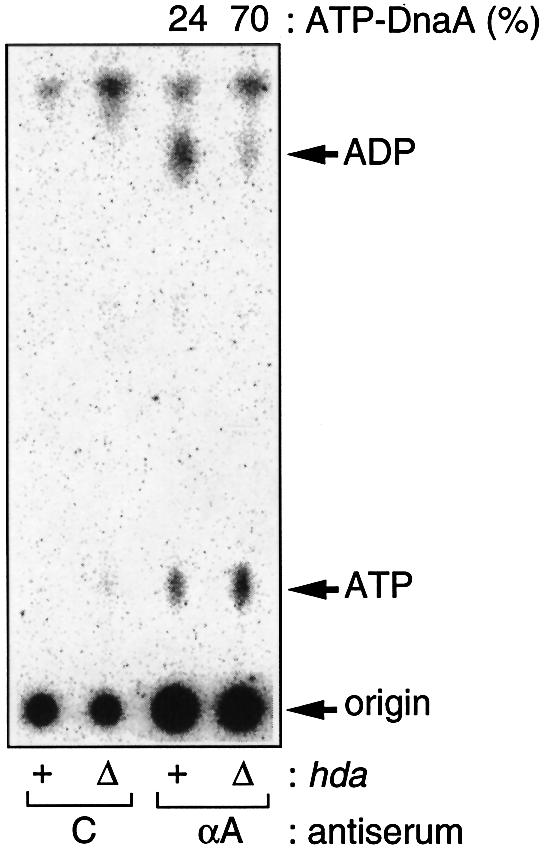

Cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate during growth at 37°C, and the nucleotides bound to the DnaA protein were assessed by immunoprecipitation and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Kurokawa et al., 1999). Results indicated that disruption of the hda gene in the oriC rnhA double mutant increased the level of ATP–DnaA to 70% (Figure 2). As the level in the oriC rnhA double disruptant in the same background strain was only 24%, as reported previously, it appears that the abundance of ATP–DnaA molecules depends on the absence of the functional hda gene (Figure 2). The total cellular content of the nucleotide-bound DnaA was not significantly affected by the hda mutation (data not shown). These findings suggest that Hda plays an essential role in the RIDA system in vivo.

Fig. 2. Accumulation of ATP–DnaA in the hda mutant. MG1655-derivative rnhA::Tn3 ΔoriC::TcR cells bearing Δhad::CmR (Δ) or hda+ (+) were grown to an optical density (A660) of 0.15 at 37°C in the presence of [32P]orthophosphate (Kurokawa et al., 1999). Nucleotide-bound DnaA protein was immunochemically isolated from cell lysates, and the recovered nucleotides were analyzed. Proportions (%) of ATP–DnaA comprising the total amount of ATP/ADP–DnaA molecules are shown. C, control using pre-immune serum; αA, anti-DnaA antiserum was used. The total cellular content of the nucleotide-bound DnaA was not significantly affected by the hda mutation. The origin and migration positions of ATP and ADP on this TLC plate are indicated. Most of the radioactivity at the origin on the TLC sheet is derived from phospholipids that bind to the DnaA protein and protein A–Sepharose specifically or non-specifically (T.Katayama, unpublished data).

Direct involvement of Hda in RIDA

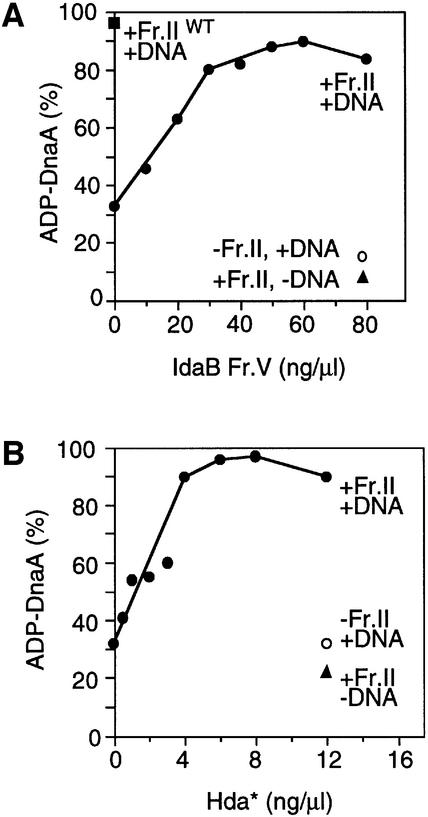

To investigate the function of Hda in the RIDA system, first, we examined the RIDA activity in the Δhda mutant extract in vitro, using conditions described previously (Katayama and Crooke, 1995; Katayama et al., 1998). Under these conditions, the RIDA reaction proceeds in a DNA replication-independent manner, presumably because high DNA concentrations and low salt conditions allow loading of the β-clamps (Katayama and Crooke, 1995). Low salt conditions allow the γ complex of pol III* to interact with DNA non-specifically, resulting in clamp loading on the supercoiled form plasmids (Stukenberg et al., 1991; Yao et al., 2000). The hydrolysis of DnaA-bound [α-32P]ATP in the presence of extracts prepared from the Δhda dnaA rnhA mutant or the parental dnaA rnhA mutant was assessed. Results revealed that the extract prepared from the Δhda strain had very little activity to promote DnaA–ATP hydrolysis, unlike that from the isogenic hda+ strain (Figure 3A, in the absence of IdaB Fr. V). These results suggest that the Hda protein is essential for RIDA, which explains the increase in level of ATP–DnaA in vivo as a consequence of the defect in RIDA function (Figure 2).

Fig. 3. In vitro complementation of RIDA activity of the hda mutant by the IdaB fraction and purified tagged Hda. (A) Extract from an hda mutant lacks IdaB activity. Crude cell extracts (fraction II) were prepared by ammonium sulfate (0.23 g/ml) precipitation of cleared lysates isolated from MG1655-derivative rnhA::Tn3 dnaA::TcR mutants bearing Δhda::CmR or hda+, as described (Katayama and Crooke, 1995). [α-32P]ATP-bound DnaA (0.6 pmol) was incubated for 20 min at 30°C in the presence (+) or absence (–) of fraction II proteins (8.0 µg) prepared from a Δhda dnaA rnhA mutant (Fr.II) or its hda+ parental strain (Fr.IIWT), M13E10 oriC plasmid (200 ng or 38 fmol as circle; DNA) and indicated amounts of partially purified IdaB fraction (IdaB Fr.V; previously designated as IdaB FT) (Katayama and Kornberg, 1994). Buffer for the reaction (5.0 µl) contained 40 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.6, 2 mM ATP, 40 mM phosphocreatine, 100 µg/ml creatine kinase, 11 mM magnesium acetate, 7% polyvinyl alcohol, and purified β-subunit (300 ng; 3.8 pmol as dimer) of pol III. The proportions (%) of ADP–DnaA comprising the total amount of ATP and ADP–DnaA molecules are plotted. The slight increase in levels of ADP–DnaA in the absence of IdaB or Hda can be attributed to the weak intrinsic ATPase activity of DnaA (Sekimizu et al., 1987; Katayama et al., 1998). (B) Tagged Hda complements the RIDA activity in the hda mutant extract. Similar experiments were carried out using the indicated amounts of purified tagged Hda (Hda*). The tagged Hda was purified as described in Materials and methods.

We suspected that the Hda protein bears IdaB activity within the RIDA system, because, among the RIDA essential factors, only the IdaB fraction had not been characterized. We examined the effect of addition of the IdaB fraction on RIDA activity. The lack of RIDA activity in the Δhda mutant extract was complemented by the IdaB protein fraction prepared from an hda wild-type strain (Figure 3A). Neither pol III* nor β-subunit alone, or both combined, complemented the defect of the mutant extract (data not shown). These results show that the hda mutant lacks IdaB activity.

In order to confirm the specific role of the Hda protein in RIDA, we constructed and purified a tagged Hda protein (Hda*). The N-terminal end of Hda was conjugated to a maltose-binding protein and purified by affinity chromatography using an amylose-conjugated resin. When purified Hda* was added to the reaction with the Δhda mutant extract, it was determined to have the same activity as that of the IdaB fraction (Figure 3B), suggesting that Hda is directly involved in RIDA and that the Hda protein itself bears IdaB activity. The specific activity of Hda* in this reaction was only ∼8-fold higher than that of the IdaB fraction. The IdaB fraction contains a protein that is detected with anti-Hda* antiserum and has the same molecular mass as the calculated mass of Hda; the content of this protein in the fraction, judged from an SDS– polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomasie Blue, seemed much less than 10% (M.Su’etsugu, A.Mizokoshi and T.Katayama, unpublished data). It is possible that modification of Hda for affinity purification decreases its activity. Polypeptides used for tagging Hda*, which were required for construction of the overproducing plasmid (see Materials and methods), may also partially interfere with its function.

Reconstitution of RIDA with purified proteins and coupling with DNA replication

In order to distinguish between the possibilities that only the Hda protein is required for IdaB activity or that it cooperates with other factors present in the Δhda mutant extract, we determined whether the RIDA reaction could be reconstituted with purified pol III*, the β-subunit and Hda* protein. We have previously reconstituted this reaction using the crude IdaB fraction and purified pol III* plus the β-subunit (Katayama et al., 1998). The same conditions were used here except for Hda*. Under these conditions, the DNA-loaded β-clamps were formed in the absence of concomitant DNA replication, due to high concentrations of the β-subunit and low salt concentrations (Katayama et al., 1998).

Results indicated that purified Hda* protein, on its own, promotes the efficient hydrolysis of DnaA-bound ATP in a manner dependent on the other RIDA components (Figure 4A). The increase in specific activity seen with Hda* was ∼6-fold, which was comparable to that obtained by the assay that included the mutant extract (Figure 3B). This suggests that the extract does not include an Hda*-specific activator or stimulator. Consistent with these results was the finding that when plasmid DNA was also concentrated to the level used in the crude extract assay (Figure 3), the concentration of Hda* required for this reconstituted RIDA reaction was much the same as that for the crude extract assay (Figure 4A, insert).

Fig. 4. In vitro reconstitution of RIDA activity using purified tagged Hda protein. (A) RIDA activity depends on the presence of tagged Hda in the system reconstituted with purified proteins. Reaction mixture (25 µl) contained purified β-subunit (3.8 pmol as dimer) and pol III* fraction V (22 U), in the presence of the indicated amounts of purified tagged Hda (Hda*; MBP-Hda-Myc′ His) or partially purified IdaB fraction (IdaB Fr.V). pol III* is a subassembly of pol III holoenzyme lacking the β-subunit. In the absence (–) of either one of pol III* (pol), the β-subunit (β), and oriC-plasmid (DNA), Hda*-dependent RIDA was not seen, as previously noted for IdaB Fr.V. The insert shows results of similar experiments carried out using a 5 µl reaction volume. (B) RIDA activity depends on tagged Hda in the DNA replication-coupled system with purified proteins. [α-32P]ATP-bound DnaA (1.0 pmol) was added to a minichromosomal replication system, along with the indicated amounts of tagged Hda (Hda*) or IdaB fraction (IdaB Fr.V), then incubated for 30 min at 30°C in the presence (+) or absence (–) of 25 µM each of the four deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs). This reaction (25 µl) contained DnaB helicase, DnaC helicase loader, DnaG primase, single strand binding protein, HU protein, gyrase and pKE101 oriC plasmid (200 ng; 600 pmol as nucleotide) in buffer, as described (Katayama et al., 1998), in addition to the β-subunit (2.5 pmol) and pol III* fraction V (34 U). Replication activity depends on the presence of dNTPs, and sliding clamps formed on nascent DNA strands are required for RIDA. (C) Depletion of tagged Hda reduces the RIDA activity. Buffer M (Katayama et al., 1998) (total 13 µl) including (+) or excluding (–) purified Hda* (1 µg), Ni-NTA–agarose (5 µl of 50% slurry in buffer M), and imidazole (200 mM) were incubated on ice for 1 h with mixing every 10 min. The supernatants were obtained by brief centrifugation, and portions (3.2 µl) were added to the reconstituted RIDA system (25 µl) excluding Hda*, as in (B) of this figure, and incubated for 20 min at 30°C. In the experiment of lane 4, Hda* (250 ng) was added back to the RIDA system before incubation. Hda* contains a histidine tag at the C-terminal and imidazole is a binding competitor for Ni-NTA (Qiagen).

We also found that the Hda* protein can function in promoting DnaA–ATP hydrolysis in a manner coupled with DNA replication (Figure 4B). For this experiment, we used a minichromosome replication system reconstituted with purified proteins (Ogawa et al., 1985; van der Ende et al., 1985; Crooke, 1995). In this replication system, there is a limited concentration of the β-subunit and a physiological salt concentration; therefore, IdaB-dependent DnaA–ATP hydrolysis is observed in a DNA replication-coupled manner (Katayama et al., 1998). Under these conditions, the RIDA reaction proceeded in a manner dependent on both the presence of the Hda* protein and concomitant DNA replication (Figure 4B). In addition, when Hda* was selectively depleted from the preparation using its tag’s affinity for a specific ligand, RIDA was severely inhibited, indicating an essential role for this protein, but not contaminant proteins in the preparation, in RIDA (Figure 4C). Taken together, these observations indicate that the Hda protein is a necessary factor that acts alone in the DNA replication-coupled, regulatory inactivation of DnaA in the presence of the pol III holoenzyme.

Over-initiation in the hda mutant and abortive elongation of the additional forks

As over-initiation occurs in the RIDA-deficient mutant (Kellenberger-Gujer et al., 1978), all of the above results suggest that Hda is required for repression of over-initiation of chromosomal replication. To investigate this theory at the chromosomal level, we isolated ts mutants of the hda gene (see Materials and methods). Using Southern blot hybridization, we examined the copy number ratio of oriC to terC (replication termination region) of a hdats (hda86) mutant and its control strain before and after incubation at the non-permissive temperature (42°C). If over-initiation occurs, the ratio of oriC to terC will increase compared with the control strain, as previously shown in over-initiating dnaA mutants (Kellenberger-Gujer et al., 1978; Atlung et al., 1987).

As shown in Figure 5A, the oriC/terC ratio increased following inactivation of Hda. A 3- to 4-fold increase in this ratio was observed after 1–2 h incubation at 42°C, which was comparable to results obtained when wild-type DnaA protein was overproduced using the phage λ pL promoter (Atlung et al., 1987). Even at the permissive temperature (30°C), the ratio in the hda86 mutant was slightly higher than that in the control strain; the mutant Hda might be partially denatured at this low temperature, but not enough to affect growth as the rate of growth of the mutant cells at 30°C was comparable to that of the control strain (data not shown). The cellular DnaA content in the hda86 mutant was similar to that in the control strain at 30 and 42°C (data not shown). When the wild-type hda-bearing plasmid was introduced into the hda86 mutant, the increase in the oriC/terC ratio was not observed (Figure 5B). This indicates that the increase in the ratio is a result of the defect of the hda gene. One interpretation for these results is that over-initiation occurs in the hda mutant at 42°C.

Fig. 5. Over-initiation and abortive elongation in the hda mutant. (A) Growing cultures of the hdats and hdatr strains at 30°C were shifted similarly to 42°C, and at the indicated times portions of the culture were harvested to quantify the copy numbers of the chromosomal oriC and terC sites in a Southern hybridization experiment using specific probes. The ratio of the oriC/terC sites in the hdatr strain at time 0 is defined as 1.0, and the relative values are shown. Results shown are the averages of data from independently duplicated experiments, the error range being ±15%. (B) Similar analyses of the quantitative Southern hybridization experiments were carried out using the strains containing pACYC184-hda+ (+) or pACYC184-hda– (–). pACYC184-hda– is the pACYC184-hda+ derivative, which has an ApR marker inserted within hda. Cultures harvested at 30°C just before the temperature shift-up (30) and after incubation at 42°C for 2 h (42) were used. The ratio of the oriC/terC sites in the hdatr strain bearing the pACYC184-hda– plasmid at 30°C is defined as 1.0, and relative values are shown. (C) The quantitative dot-blot analyses were performed using hdats and hdatr strains, and the relative copy numbers of the oriC site in a unit cell volume were deduced. Similar calculations were carried out for the terC site.

Studies on the dnaA mutants and a DnaA overproducer have shown that two types of over-initiation can occur: one leading to over-replication of the whole chromosome (Kellenberger-Gujer et al., 1978; Katayama and Kornberg, 1994; Nyborg et al., 2000) and the other leading to over-replication only in the vicinity of the oriC region because of abortive elongation (Atlung and Hansen, 1993; Nyborg et al., 2000). Over-initiation occurring in the dnaAcos mutant is an example of the former type and over-initiation caused by overproduction of wild-type DnaA protein is an example of the latter type. The mechanism responsible for the arrest of the fork movement is unknown; however, it has been proposed that abnormal DnaA–pol III interaction causes this defect (Nyborg et al., 2000). To characterize further the replication pattern of the hda86 mutant, we measured the copy number of the oriC and terC regions per cell mass using quantitative dot-blot analysis. The copy number of oriC was increased abnormally in the mutant (Figure 5C), indicating that over-initiation indeed occurred when Hda was inactivated.

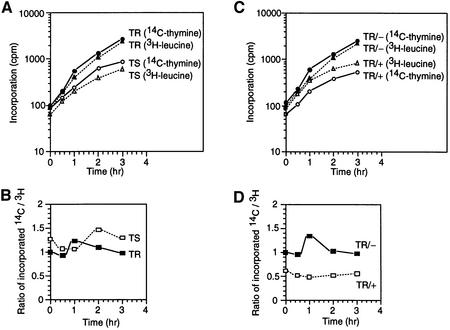

Interestingly, the copy number of the terC region per cell mass was decreased by inactivation of Hda (Figure 5C). We were interested in the bulk rate of DNA replication of the hda86 mutant. When the rates of DNA synthesis and protein synthesis were examined by measuring incorporation of labeled thymine and leucine, the rate of DNA synthesis only increased slightly in the hda86 mutant upon a shift-up in temperature (Figure 6A) as compared with the rate of protein synthesis (Figure 6B). These results indicate that the excessive formation of replication forks was aborted.

Fig. 6. The ratio of DNA replication and protein synthesis activities. Bulk chromosomal replication and protein synthesis were assessed by quantifying incorporation of [14C]thymine and [3H]leucine. Growing cultures of hdats (TS) and hdatr (TR) strains at 30°C were used for temperature shift experiments (A and B). Growing cultures of the hdatr strain (TR) containing pACYC184-hda+ (+) or pACYC184-hda– (–) were diluted and shifted to 42°C at time 0 (C and D). Incorporation into portions of cells (A and C) and the ratios of chromosome replication and protein synthesis activities (B and D) at the indicated times are shown.

Although the initiated replication was abortive, the chromosome replication was over-initiated in the hda mutant, indicating that in the initiation step, Hda represses the initiation of replication in vivo. This negative role for Hda in chromosome replication was also supported by findings from the experiment on the bulk rate of DNA replication in a Hda overproducer. The rate of DNA synthesis was decreased by a moderate oversupply of Hda using the multicopy hda plasmid (Figure 6C), which was evident when compared with the rate of protein synthesis (Figure 6D).

Discussion

By screening for genes involved in the stable maintenance of the mini-F plasmid, we have identified a novel essential gene, hda, which codes for a protein structurally related to the DnaA protein. We showed in vivo that the active form of the DnaA protein was excessively increased in the hda disruptant. Furthermore, we demonstrated in vitro that an extract of the hda-disruptant cells was unable to produce RIDA activity and that this defect could be complemented by the IdaB fraction prepared from a hda wild-type strain or by the purified tagged Hda protein. With the purified tagged Hda and other purified proteins, we were also able to reconstruct the RIDA reaction. These results indicate that the Hda protein is an essential factor for RIDA. Moreover, we showed that over-initiation occurs in the hdats mutant at the non-permissive temperature. Therefore, this protein must play a key role in the control switch of the chromosomal replication cycle by timely inactivation of the initiator so that the once-per-cell-cycle rule of replication is ensured.

Until now, the crude IdaB fraction was necessary for the in vitro RIDA assay. Purification of the essential factor(s) from this IdaB fraction has not been successful. However, in this study, following identification of Hda, the crude IdaB fraction could be replaced by purified tagged Hda and the RIDA activity reconstituted with purified proteins in vitro. The Hda protein was identified in the IdaB fraction by immunoblotting (M.Su’etsugu, A.Mizokoshi, and T.Katayama, unpublished data). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other regulatory factors are present in the IdaB fraction. Further characterization of the IdaB fraction will be necessary to clarify its functions in RIDA.

Abortive elongation has previously been observed in cells oversupplied with wild-type DnaA (Atlung and Hansen, 1993; Nyborg et al., 2000). This was also observed in the hda mutant (with a wild-type dnaA gene), but not in the dnaAcos (Katayama and Kornberg, 1994) mutant or the multicopy dnaA46 strain (Nyborg et al., 2000) (Figure 8). Therefore, wild-type DnaA is likely to be involved in the control of the elongation rate of replication. These two mutant DnaA proteins lack affinity for ATP/ADP (Katayama, 1994; Messer and Weigel, 1996), suggesting that the nucleotide-bound form of DnaA is involved in the control of movement of the replisome. DnaA might affect the processivity of the replicase through interaction with the β-subunit of the sliding clamp.

Although over-initiation was observed in the hda mutant, the apparent level of over-initiation was lower than that of the dnaAcos mutant (Kellenberger-Gujer et al., 1978). The level in the hda mutant may be an underestimate because of the abortive elongation resulting in degradation of the partially replicated molecules. Alternatively, the initiation may be repressed by a system other than RIDA, and the DnaAcos protein also may be defective in that system.

Hda is a member of the chaperone-related AAA+ family. The Hda protein may interact with ATP, resulting in hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond (Neuwald et al., 1999). The overall sequence of the Hda protein has significant similarity to the DnaA domain III (Figure 1) rather than to other members of the AAA+ family. Several proteins in this family function as homo- or hetero-oligomers, acquiring a hexameric ring form with enhanced ATPase activity (Matveeva et al., 1997; Babst et al., 1998; Cai, 1998; Schirmer et al., 1998). With this background in mind, we may speculate that on the ring-shaped sliding clamp, the Hda protein would form a hetero-oligomer with DnaA to create a catalytic center for efficient hydrolysis of DnaA-bound ATP.

Potential Hda homologs, identified as proteins structurally related to DnaA domain III with a molecular mass similar to that of the E.coli Hda protein, have been found in completely sequenced genomes of E.coli O157:H7, Haemophilus influenzae, Xylella fastidiosa, Neisseria meningitidis MC58, N.meningitidis Z2491 and Rickettsia prowazekii. In 22 other sequenced prokaryotic genomes, we could not find any candidates. Proteins with different structural features may play the same role as Hda. Alternatively, the regulatory system involving Hda– DnaA may be specific to some groups of bacteria.

In eukaryotes, many AAA+ proteins participate in the (pre)replicative complex formation for initiation of chromosome replication, e.g. three subunits of ORC (Orc1p, Orc4p and Orc5p), Cdc6p, and all six subunits of MCM2-7 (Stillman, 1996; Baker and Bell, 1998; Neuwald et al., 1999). ORC, Cdc6p and MCMs are most likely functional counterparts of DnaA, DnaC and DnaB, respectively (Baker and Bell, 1998). There may also be functionally analogous subunits to DnaA and Hda in ORC. As E.coli pol III* and the β-subunit are structural and functional homolog of RF-C-associated DNA pol δ and the sliding clamp protein PCNA (Stillman, 1994; Baker and Bell, 1998), the system for regulating inactivation of the initiator may be conserved throughout evolution. Interestingly, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Orc1p protein binds and hydrolyzes ATP, and ATP binding is necessary for the ORC to bind to the origin of replication (Lee and Bell, 2000). The human Cdc6p protein (HuCdc6p) also binds and hydrolyzes ATP (Herbig et al., 1999). The binding of ATP and its hydrolysis have separate roles during DNA replication, which is consistent with the results of studies on the mutations in S.cerevisiae Cdc6p (Perkins and Diffley, 1998; Wang et al., 1999; Weinreich et al., 1999). Based on these results, it is believed that ATP regulates activity of these replication proteins (Lee and Bell, 2000). The regulatory system, in which ATP binding and hydrolysis by AAA+ ATPases acts as a molecular switch, may control the initiation of DNA replication in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Materials and methods

Identification of hda

Mutants, in which a mini-F plasmid was not stably maintained, were isolated at 30°C, essentially as described (Niki et al., 1988). The cells of strain C600 lacI::KmR rpsL recAΔ::Tn10 carrying a mini-F plasmid with the lacIq gene, pXX325Iq, were mutagenized with 5% ethyl-methane sulfonate for 30 min at 30°C. The cells were washed, suspended in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin (Ap), and incubated overnight at 30°C. The culture was diluted, spread on LB plates containing Ap and X-gal, and incubated at 30°C. Pale blue mutants were isolated and, from these, ts mutants were selected at 42°C and transformed with an E.coli DNA library constructed with pACYC184 vector. The mutant genes and suppressing genes were identified by the method of insertion of ApR gene cassettes, as described (Yokochi et al., 1996). The plasmid pXX325Iq was constructed by cloning a lacIq fragment into the SalI site of pXX325 (Ogura and Hiraga, 1983). The lacIq fragment was prepared by PCR with the oligonucleotides lacICX (5′-CCCTCGAGACATTAATTGCGTTGCGCTCA-3′) and lacINX (5′-CCCTCGAGGGATGTTGATGCAATGGTGG-3′) as primers and cell suspensions of JM109 as templates. Product was digested with XhoI.

Disruption of hda on the chromosome

The hda DNA fragment, amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 336-1 (5′-CCAAGCTTGTATCTCGATCTGGCTACTG-3′) and 336-2 (5′-CCAAGCTTTTATCGTGAAGAAAGCGGGG-3′) as primers and digested with HindIII, was cloned into the HindIII site of pUC19. Using this as a template, the Δhda fragment lacking most of the hda coding region was prepared by PCR with oligonucleotides 336-15 (5′-CCGCGGCCGCGGTGTTTATTGTCGGATGCG-3′) and 336-16 (5′-CCGCGGCCGCTACCACAGAATCCCATGATG-3′) as primers, and then ligated with a CmR cassette. The resultant Δhda::CmR plasmid was introduced into a polAts mutant containing the hda+-mini-F plasmid, and the hda disruptant was isolated by replacing the chromosomal hda+ with Δhda::CmR as described (Kato et al., 1985).

In vitro analyses of RIDA

Nucleotide-bound DnaA was isolated by specific immunoprecipitation and recovered nucleotides were separated using polyethylenimine (PEI)–cellulose TLC, as described (Katayama et al., 1998). Relative amounts of radioactivity for ATP and ADP were quantified using a Bioimage analyzer BAS 2500 (Fujix, Japan). The low level of ADP–DnaA is caused by weak ATPase activity intrinsic in DnaA (Sekimizu et al., 1987).

Construction and purification of the tagged Hda

The plasmid for producing the tagged Hda (MBP-Hda-Myc′ His) was constructed as follows: a hda DNA fragment was prepared by PCR with oligonucleotides 336-9 (5′-CCCTGCAGCAACTTCAGAATTTCTTTCACA-3′) and 336-5 (5′-CCCTGCAGTAGTTCGGATAAGGCGTTC-3′) as primers, and then ligated with a plasmid fragment of pBAD/Myc His A (Invitrogen, CA). Using the ligation products as a template, the hda-myc′ His DNA fragment was prepared by PCR with oligonucleotides 336ATG (5′-ATGGTAAACTTCTCGCGATTTTG-3′) and MycXba (5′-CCTCTAGATTCGCAACGTTCAAATCCGC-3′) as primers and ligation with the StuI–XbaI fragment of the plasmid pMAL-c (NEB, Beverly, MA). The structure of the cloned hda fragment and activity of the tagged Hda protein were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing and a complementation test for hdats mutants in the absence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, respectively. The tagged Hda protein was purified essentially according to the manufacturer’s protocol for pMAL-c. We could obtain the plasmid for MBP-Hda-Myc′ His as above, but not the plasmids for the other tagged Hda (MBP-Hda and Hda-Myc′ His). This was probably because MBP-Hda-Myc′ His was less active. The purity of Hda* was >90%, as judged by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining.

In vivo analysis for DnaA forms

MG1655-derivative rnhA::Tn3 ΔoriC mutants bearing Δhda::CmR or hda+, constructed by P1 transduction, were grown at 37°C in a supplemented TG medium excluding NaCl and containing [32P]ortho phosphate (0.4 mCi/ml), as described (Katayama et al., 1998). Nucleotides bound to the DnaA protein were isolated by immunoprecipitation of DnaA from cleared lysates, and analyzed using PEI–cellulose TLC, as described (Katayama et al., 1998).

Isolation of the hdats mutant

The hdats mutant was isolated by plasmid shuffling (Kato and Ikeda, 1996). The hda DNA fragment was prepared by error-prone PCR in the presence of 0.2 mM MnCl2 with the oligonucleotides 336-17 (5′-CCGGATCCGTATCTCGATCTGGCTACTG-3′) and 336-18 (5′-CCGGATCCTTATCGTGAAGAAAGCGGGG-3′) as primers, and cloned into a mini-F vector, pJK282 (KmR) (Kato et al., 1988) The resultant plasmid was introduced into the strain MG1655 Δhda recA/mini-F-hda+ (ApR). The KmR ApS transformants were isolated at 30°C and ts mutants were selected at 42°C. The hdats fragments were amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 336-12 (5′-CCATCGATTTATCGTGAAGAAAGCGGG-3′) and 336-4 (5′-CCGCGGCCGCTAGTTCGGATAAGGCGTTCG-3′) as primers. The chromosomal DNA fragment containing the hda-downstream region was also amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 336-13 (5′-CCAAGCTTAGCCAATGAGGCGATCAATC-3′) and 336-14 (5′-CCGGATCCTCCATAGTATTCGTAGGCCG-3′) as primers. These two fragments were ligated to yield a ‘hdats-KmR-ApR-downstream region’, and the fragment was amplified by PCR. The resultant product was introduced into the strain for ‘ET cloning’ (Zhang et al., 1998), MG1655 rpsL thyA leu/pBAD-ETγ Cm, a CmR ApS derivative (J.Kato, unpublished data) of pBAD-ETγ (Zhang et al., 1998), and ApR colonies were isolated. ts and temperature-resistant (tr) colonies were selected and used as the hdats and hdatr strains, respectively. The hdats allele used was hda86.

In vivo analyses of DNA replication

To measure the rates of chromosomal DNA replication and protein synthesis, early stationary phase culture was diluted 40-fold in Antibiotic medium 3 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) containing [14C]thymine (23.6 µCi/ml) and [3H]leucine (47.2 µCi/ml), and incubated at 30°C for 3 h. This culture was again diluted 20-fold in the same medium and incubated at 42°C. Portions were withdrawn at intervals, and incorporated radioactivities were measured by liquid scintillation counting.

For analysis of the copy number ratio of oriC to terC, cells were grown in LB medium containing 40 µg/ml thymine for 2 h at 30°C, diluted 20-fold in NaCl-depleted LB medium containing 40 µg/ml thymine and grown at 42°C. Portions were withdrawn at intervals, and chromosomal DNA was prepared using the DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), digested with BamHI, and analyzed by Southern hybridization using probes obtained by PCR with primer oligonucleotides 451-25 (5′-CTGTGAATGATCGGTGATCC-3′) and 451-26 (5′-AGCTCAAACGCATCTTCCAG-3′) for detection of the oriC region, and 254-1 (5′-CAGAGCGATATATCACAGCG-3′) and 254-2 (5′-TATCTTCCT GCTCAACGGTC-3′) for the terC region.

For measurement of gene dosages of oriC and terC per cell mass, cells were grown under the same conditions as above. The total cell mass was normalized between the hdats and hdatr strains, then samples were incubated in 50 µl of the lysozyme solution, boiled for 5 min in the presence of 0.5 N NaOH (400 µl), and used for dot-blotting and hybridiz ation with the primers described above (Katayama and Nagata, 1991).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs S.Hiraga and T.Miki for support in this work, to Dr T.Ogura for valuable comments on AAA+ proteins, and to Dr Y.Sakakibara for gifts of strains and for helpful discussion. We also thank Drs T.Kawabata and K.Nishikawa for helpful comments on the structure of Hda, D.Aoki, Y.Aoyagi, T.Mizuno, Y.Imai, N.Chiku and T.Ikegami for technical assistance, and M.Ohara for language assistance. This study was supported in part by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

References

- Atlung T. and Hansen,F.G. (1993) Three distinct chromosome replication states are induced by increasing concentrations of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 175, 6537–6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlung T., Lobner-Olesen,A. and Hansen,F.G. (1987) Overproduction of DnaA protein stimulates initiation of chromosome and minichromosome replication in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 206, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M., Wendland,B., Estepa,E.J. and Emr,S.D. (1998) The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J., 17, 2982–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T.A. and Bell,S. (1998) Polymerases and the replisome: machines within machines. Cell, 92, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow J.J. and Laskey,R.A. (1988) A role for the nuclear envelope in controlling DNA replication within the cell cycle. Nature, 332, 546–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boye E., Stokke,T., Kleckner,N. and Skarstad,K. (1996) Coordinating DNA replication initiation with cell growth: differential roles for DnaA and SeqA proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 12206–12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boye E., Lobner-Olesen,A. and Skarstad,K. (2000) Limiting DNA replication to once and only once. EMBO Rep., 1, 479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendler T. and Austin,S. (1999) Binding of SeqA protein to DNA requires interaction between two or more complexes bound to separate hemimethylated GATC sequences. EMBO J., 18, 2304–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. (1998) ATP hydrolysis catalyzed by human replication factor C requires participation of multiple subunits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11607–11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke E. (1995) DNA synthesis initiated at oriC: in vitro replication reactions. Methods Enzymol., 262, 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley J.F. (1996) Once and only once upon a time: specifying and regulating origins of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev., 10, 2819–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan S., Harwood,J., Drury,L.S. and Diffley,J.F. (1997) Cdc6p-dependent loading of Mcm proteins onto pre-replicative chromatin in budding yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 5611–5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbig U., Marlar,C.A. and Fanning,E. (1999) The Cdc6 nucleotide-binding site regulates its activity in DNA replication in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 2631–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T. (1994) The mutant DnaAcos protein which overinitiates replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome is inert to negative regulation for initiation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 22075–22079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T. and Crooke,E. (1995) DnaA protein is sensitive to a soluble factor and is specifically inactivated for initiation of in vitro replication of the Escherichia coli minichromosome. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 9265–9271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T. and Kornberg,A. (1994) Hyperactive initiation of chromosomal replication in vivo and in vitro by a mutant initiator protein, DnaAcos, of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 12698–12703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T. and Nagata,T. (1991) Initiation of chromosomal DNA replication which is stimulated without oversupply of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 226, 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T., Kubota,T., Kurokawa,T., Crooke,E. and Sekimizu,K. (1998) The initiator function of DnaA protein is negatively regulated by the sliding clamp of the E.coli chromosomal replicase. Cell, 94, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J. and Ikeda,H. (1996) Construction of mini-F plasmid vectors for plasmid shuffling in Escherichia coli. Gene, 170, 141–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J., Suzuki,H. and Hirota,Y. (1985) Dispensability of either penicillin-binding protein-1a or 1b involved in the essential process for cell elongation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 200, 272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J., Nishimura,Y., Yamada,M., Suzuki,H. and Hirota,Y. (1988) Gene organization in the region containing a new gene involved in chromosome partition in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 170, 3967–3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger-Gujer G., Podhajska,A.J. and Caro,L. (1978) A cold sensitive dnaA mutant of E.coli which overinitiates chromosome replication at low temperature. Mol. Gen. Genet., 162, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman Z. and O’Donnell,M. (1995) DNA polymerase III holoenzyme: structure and function of a chromosomal replicating machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 64, 171–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa R., Mitsuki,H., Okazaki,T. and Ogawa,T. (1996) A novel DnaA protein-binding site at 94.7 min on the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol. Microbiol., 19, 1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa R., Ozaki,T., Moriya,S. and Ogawa,T. (1998) Negative control of replication initiation by a novel chromosomal locus exhibiting exceptional affinity for Escherichia coli DnaA protein. Genes Dev., 12, 3032–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogoma T. (1997) Stable DNA replication: interplay between DNA replication, homologous recombination and transcription. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 61, 212–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K., Nishida,S., Emoto,A., Sekimizu,K. and Katayama,T. (1999) Replication cycle-coordinated change of the adenine nucleotide-bound forms of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 18, 6642–6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.G. and Bell,S.P. (2000) ATPase switches controlling DNA replication initiation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Campbell,J.L., Boye,E. and Kleckner,N. (1994) SeqA: a negative modulator of replication initiation in E.coli. Cell, 77, 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva E.A., He,P. and Whiteheart,S.W. (1997) N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein contains high and low affinity ATP-binding sites that are functionally distinct. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 26413–26418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer W. and Weigel,C. (1996) Initiation of chromosome replication. In Neidhardt,F.C. et al. (eds), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 1579–1601.

- Neuwald A.F., Aravid,L., Spouge,J.L. and Koonin,E.V. (1999) AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res., 9, 27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki H., Ichinose,C., Ogura,T., Mori,H., Morita,M., Hasegawa,M., Kusukawa,N. and Hiraga,S. (1988) Chromosomal genes essential for stable maintenance of the mini-F plasmid in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 170, 5272–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg M., Atlung,T., Skovgaard,O. and Hansen,F.G. (2000) Two types of cold sensitivity associated with the A184→V change in the DnaA protein. Mol. Microbiol., 35, 1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Baker,T.A., van der Ende,A. and Kornberg,A. (1985) Initiation of enzymatic replication at the origin of the Escherichia coli chromosome: contributions of RNA polymerase and primase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 3562–3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T. and Hiraga,S. (1983) Partition mechanism of F plasmid: two plasmid gene-encoded products and a cis-acting region are involved in partition. Cell, 32, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins G. and Diffley,J.F. (1998) Nucleotide-dependent prereplicative complex assembly by Cdc6p, a homolog of eukaryotic and prokaryotic clamp-loaders. Mol. Cell, 2, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer E.C., Queitsch,C., Kowal,A.S., Parsell,D.A. and Lindquist,S. (1998) The ATPase activity of Hsp104, effects of environmental conditions and mutations. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 15546–15552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimizu K., Bramhill,D. and Kornberg,A. (1987) ATP activates dnaA protein in initiating replication of plasmids bearing the origin of the E.coli chromosome. Cell, 50, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seror S.J., Casaregola,S., Vannier,F., Zouari,N., Dahl,M. and Boye,E. (1994) A mutant cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase affecting timing of chromosomal replication initiation in B. subtilis and conferring resistance to a protein kinase C inhibitor. EMBO J., 13, 2472–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman B. (1994) Smart machines at the DNA replication fork. Cell, 78, 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman B. (1996) Cell cycle control of DNA replication. Science, 274, 1659–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenberg P.T., Studwell-Vauqhan,P.S. and O’Donnell,M. (1991) Mechanism of the sliding β-clamp of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 11328–11334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Knapp,D. and Nasmyth,K. (1997) Loading of an Mcm protein onto DNA replication origins is regulated by Cdc6p and CDKs. Cell, 90, 649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye B.K. (1999) MCM proteins in DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 68, 649–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ende A., Baker,T.A., Ogawa,T. and Kornberg,A. (1985) Initiation of enzymatic replication at the origin of the Escherichia coli chromosome: primase as the sole priming enzyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 3954–3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Freiesleben U., Rasmussen,K.V. and Schaechter,M. (1994) SeqA limits DnaA activity in replication from oriC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 14, 763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Feng,L., Hu,Y., Huang,S.H., Reynolds,C.P., Wu,L. and Jong,A.Y. (1999) The essential role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC6 nucleotide-binding site in cell growth, DNA synthesis and Orc1 association. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 8291–8298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich M., Liang,C., Stillman,B. (1999) The Cdc6p nucleotide-binding motif is required for loading mcm proteins onto chromatin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao N., Leu,F.P., Anjelkovic,J., Turner,J. and O′Donnell,M. (2000) DNA structure requirements for the Escherichia coliγ complex clamp loader and DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 11440–11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokochi T., Kato,J. and Ikeda,H. (1996) Construction of β-lactamase-encoding ApR gene cassettes for rapid identification of cloned genes. Gene, 170, 143–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Buchholz,F., Muyrers,J.P.P., Stewart,A.F. (1998) A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nature Genet., 20, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]