Abstract

Most of the approaches used to correct gene mutations in mammalian cells involve the targeting of short nucleotide molecules to homologous chromosomal sequences and the replacement of resident sequences via homologous recombination and mismatch repair. The limited efficiency and inconsistent reproducibility of these techniques are major constraints to their use in gene therapy. One of the main problems is that it is impossible to obtain reproducible results when the targeted gene loci differ. We investigated the effects of flanking sequences on homologous recombination by means of an in vitro assay of the efficiency of oligonucleotide targeting to its homologous sequence on a large duplex molecule in a reaction catalysed by the Escherichia coli RecA protein. We demonstrated that polypurine·polypyrimidine tracts (PPTs) in duplex DNA strongly stimulate the formation of D-loops with short oligodeoxynucleotides. This result was reproduced with various PPT sequences and oligonucleotides. The stimulatory effect was observed at loci as far as 4000 bp from the PPT. The formation of complexes between the oligonucleotide and the duplex molecule depended on the extent of sequence similarity between the two DNAs and the presence of the RecA protein. The stimulatory effect was inhibited by excess RecA and restored by adding heterologous DNA. We suggest that PPT sequences induce conformational changes in duplex DNA, leading to the aggregation of molecules, facilitating homology searches. We com pared, in vivo, the efficiency of the oligonucleotide-mediated correction of a URA3 chromosomal mutation for sequences with and without a PPT sequence in the vicinity. Consistent with our in vitro results, the efficiency of correction was eight times higher in the presence of the PPT sequence.

INTRODUCTION

Many ‘gene repair’ approaches have been developed with the aim of correcting point mutations in eukaryotic cells. Most of these approaches involve the targeting of short nucleic acid ‘correcting’ molecules to the homologous chromosomal sequence and replacement of the resident sequence via homologous recombination and mismatch repair. Various types of ‘correcting’ molecule have been used, including small DNA fragments (1), RNA–DNA chimeric oligonucleotides (2), triple helix-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) for mutagenesis (3) and short DNA fragments or oligonucleotides directed by triple helix-forming molecules (4–6). In each case, the method has drawbacks, such as limited efficiency and lack of reproducibility. Despite increasing evidence that homologous recombination occurs in all living cells, very little is known about the factors affecting its efficiency. The delivery of the ‘correcting’ sequence to the nucleus is one of the key problems. However, even if this step is successful, the efficiency of correction remains low and unpredictable. The efficiency of homologous recombination depends on a number of factors: the type of cell transfected, position in the cell cycle at the time of transfection, the accessibility of the targeted sequence, the target sequence and the chemical nature of the ‘correcting’ molecule.

The process by which a DNA fragment finds its homologous site in mammalian cells is not fully understood, but it is thought that RecA-like factors (such as Rad51) catalyse a homology search and mediate DNA pairing in an intricate, energy-dependent manner. RecA catalyses the binding of oligonucleotides to complementary sequences in DNA (7). However, it is difficult to use this method for gene therapy. The strictness of Watson–Crick base pairing can be overcome by displacement loop (D-loop) formation, which should not place limits on the targeting sequence. However, this process is hindered by a number of major thermodynamic and kinetic barriers. These barriers could be overcome if the rate of D-loop formation could be accelerated and if the D-loop could be stabilised. Various studies have helped to identify the factors affecting recombination in vitro. The main approach used has been to study strand exchange, a process requiring the enzyme-catalysed hybridisation of a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecule to its complementary sequence within a duplex DNA molecule (8–10). We chose to study this reaction, using oligonucleotides in reactions catalysed by RecA. The RecA protein initiates pairing by binding to ssDNA, forming a helical nucleoprotein filament (11). Stoichiometric measurements have indicated that the ratio of protein to DNA is approximately one monomer of RecA per 3 or 4 nt (12). A nucleoprotein filament as short as 15 bases long can pair with a homologous duplex DNA sequence, yielding synaptic complexes consisting of the oligonucleotide and duplex DNA stabilised by RecA. The homologous DNAs remain paired to each other after the removal of RecA if the homologous region is at least 26 bp long (7). This intermediate is probably formed in vivo, and provides a substrate for the resolution of junctions and mismatch repair of the heteroduplex.

Polypurine·polypyrimidine tract (PPT) sequences can be recognised by an oligonucleotide from the major groove, resulting in formation of a triple-helical nucleic acid structure, in which the oligonucleotide forms Hoogsteen or reverse Hoogsteen base pairs with the purines already engaged in Watson–Crick base pairs. This property has been used to enhance gene targeting by homologous recombination (13), as the ‘correcting’ sequence in this case was carried by a TFO, binding in the vicinity of the target sequence. This association greatly stimulated D-loop formation in vitro (6) and recombination ex vivo (4). However, these studies did not investigate the specific effect of the PPT sequence on D-loop formation in the absence of TFO. Here, we demonstrate that the presence of a PPT sequence in duplex DNA strongly stimulates the formation of D-loops with short oligodeoxyribonucleotides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurogentec (Sering, Belgium) and purified on fine quick-spin Sephadex G-25 columns (Boehringer, Mannheim). Concentrations were determined at 25°C by measuring molar extinction coefficients at 260 nm, calculated by a nearest-neighbour method (14).

Seven oligonucleotides identical in sequence to sequences located at positions on the YEpURA plasmid were used for D-loop experiments (see Fig. 1). Their sequences are: 40Y2, 5′-CGC GTG GCC AGC TAC ATA TAA GTA ACG TGC TGC TAC TCA T-3′; 40Y3, 5′-AGA ACA AAA ACT AGC AGG AAA CGA AGA TAA ATC ATG ATC G-3′; 40Y43, 5′-CCT AGT CCT GTT GCT GCC TAG CTA TTT AAT ATC ATG CAC G-3′; 40y83, 5′-AAA AGC AAA CAA ACT TGT GTG CTT GAT TGG ATG TTC GTA C-3′; 40Y123, 5′-CAC CAA GGA ATT ACT GGA GTA AGT TGA AGC ATT AGG TCC C-3′; 40Y382, 5′-CCA GGT ATT GTT AGC GGT TTG AAG CAG GCG GCA GAA GAA G-3′; 40Y3460, 5′-TAT TGT TCA CTA TCC CAA GCG ACA CCA TCA CCA TCG TCT T-3′. The number at the end of each oligonucleotide name indicates the distance (in bases) between the polypurine· polypyrimidine sequence and the oligonucleotide. Another oligonucleotide R60, 5′-AAT ATC GCG GCT CAG TTC GAG CAT GCT GTT TCT GGT CTT CAC CCA CCG GTA CGG GTC TT-3′ is homologous to the pCH110 sequence. TFO1 (Acr-5′-uOuuuTOTuuuGgGGgG-3′) consists of 5-propynyl-deoxyuracils (u), 5-methyl-deoxycytosines (O), deoxyguanines (G), 7-deazadeoxyguanine (g) and 5′-tethered acridine derivatives (Acr), as previously described (6).

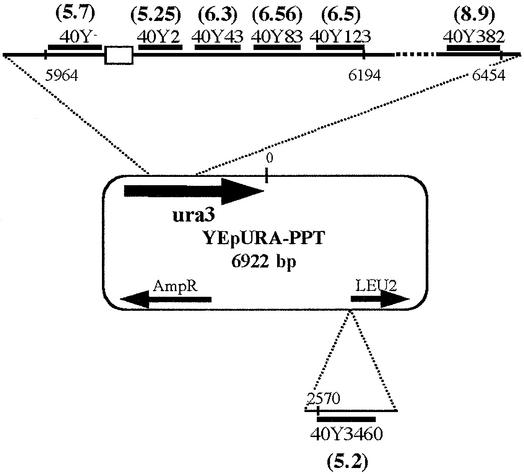

Figure 1.

Location of the various oligonucleotides tested for joint molecule formation with YEpURA plasmids. The numbers in parentheses indicate the extent to which joint molecule formation was stimulated (as a factor), as estimated from the ratio of the number of joint molecules formed with the YEpURA-PPT plasmid to the number of complexes formed with the YEpURA plasmid.

The EB34 oligonucleotide was used in vivo for URA3-CT correction: 5′-CGC GTG GCC AGC TAC ATA TAA GTC ACG TGC TGC TAC TCA T-3′. It restores the reading frame of the URA3 gene by removing the two-base insertion in the URA3-CT mutant at position 21 with respect to the ATG of the coding sequence.

Plasmids and strains

Two sets of plasmids were used to prepare duplex DNA. One set was derived from YEpURA3.22 (6922 bp), and the other from pCH110 (7128 bp). The YEpURA-PPT plasmid was constructed by introducing a 42 bp sequence, containing an 18 bp oligopyrimidine·oligopurine tract (5′-AGAAAAGAA AAGGGGGGA-3′) five codons after the ATG initiation codon of the URA3 gene in YEpURA3.22 (a gift from Dr Barre). YEpURA was obtained by removing the 31 bp MluI restriction fragment, containing the PPT, from YEpURA-PPT. pCH110-PPT was constructed by introducing a 48 bp sequence containing another 17 bp oligopyrimidine·oligopurine tract (5′-AAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGG-3′) 40 codons after the ATG codon of the lacZ gene in pCH110. pUC19, M13mp19, YEpLEU and a λ DNA PCR fragment were used as heterologous DNA. The 2962 bp λ PCR fragment was amplified, using 5′-TGGTGATGCCGAGAA-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GCCCGTGCCGTGGAG-3′ as the reverse primer.

Strain ORT3453 was constructed by introducing the PPT sequence of the YEPURA-PPT plasmid into the URA3 gene of the ORT3458 strain. The ORT3458 strain is a derivative of S288c, with a HindIII restriction site at position 21 in the URA3 gene. The chromosomal sequence of both strains that is corrected by EB34 is 5′-CGC GTG GCC AGC TAC ATA TAA GCT TC ACG TGC TGC TAC TCA T-3′.

Joint molecule assays

We first incubated 0.5 µM labelled ssDNA with 20 mM Tris–HCl and 12.5 mM MgCl2 (D-loop buffer) in the presence or absence of 7 µM RecA, 0.3 mM ATP-γ-S and 1.1 mM ADP, at 37°C for 10 min. The plasmid (0.01 µM) was then added (time zero). Concentrations of DNA are expressed in micromoles of DNA molecules. The final reaction volume was 10 µl. At the indicated time, one volume of stop buffer (1% SDS, 20 mM EDTA) was added to the reaction mixture. The samples were subjected to electrophoresis at 4°C for 2 h (150 mA) in a 0.8% agarose gel containing Tris-borate buffer (pH 8) supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2. The gel was then dried and analysed with a phosphorimager.

Protein binding assays

We used a BIAcore 2000 (BIAcore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) to analyse protein binding. The fluid system consisted of four detection surfaces located in separate flow cells accessible either individually or serially in multichannel mode. Oligonucleotides were immobilised on the detection surfaces and proteins were continuously passed over the surface together with buffer A [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2), 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2], at a flow rate of 10 µl/min and a temperature of 37°C. The proteins and buffer A were injected at time zero. If RecA was used, 0.5 mM ATP-γ-S was added. Surfaces were regenerated between each binding experiment by injecting 5 µl of 0.05% SDS. The SPR response, expressed in resonance units (RU), depends on the refractive index close to the surface and is therefore directly correlated with the concentration of molecules in the surface layer (1 RU = 1 pg/mm2). Equivalent amounts of each biotin-labelled oligonucleotide (400 RU) were captured on sensor surfaces on which streptavidin had previously been fixed in our laboratory (sensor chip CM5, BIAcore). A flow cell without bound oligonucleotide was used as a reference to correct for bulk refractive index contributions, related to differences in the composition of injected samples. The complementary non-biotin-labelled oligonucleotides were hybridised in each flow cell at a flow rate of 2 µl/min.

Gene targeting assay

Exponentially growing ORT3453 and ORT3458 Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were washed in DTT (25 mM) for 10 min, and resuspended in electroporation buffer (0.25 M saccharose, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 1 mM MgCl2) at a concentration of 109 cells/ml. The pLeu plasmid and the EB34 oligonucleotide were added at final concentrations of 10 and 1 µg/ml, respectively. Cells were then electroporated with the mixture in a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad) apparatus. We added 1 M sorbitol and cells were plated on a specific medium to select for LEU+ or URA+ prototrophy. The efficiency of gene targeting was calculated as the ratio of URA+ to LEU+ colonies.

RESULTS

High efficiency of D-loop formation with duplex DNA carrying a PPT sequence

Synaptic complexes were formed following the incubation of duplex DNA, such as supercoiled plasmid DNA, with a homologous oligonucleotide and RecA (Fig. 2A). RecA dissociated from these synaptic complexes following the addition of EDTA and SDS. The resulting deproteinated complexes were bound to the 32P-labelled oligonucleotide. When subjected to electrophoresis, this complex migrated to the same position as the duplex DNA. Our main aim was to estimate the efficiency of formation of synaptic complexes or closely related structures that might be intermediates in the strand exchange reaction. It was therefore useful that these structures formed stable complexes consisting solely of the two paired DNAs when RecA was removed. As very few complexes formed when RecA and the DNA substrates were incubated together in the presence of ATP (data not shown), the experiments were carried out in the presence of ATP-γ-S. The oligonucleotides were 40 nt long, providing a length of homologous sequence largely sufficient for the formation of complexes (7). To optimise complex recovery, we added 5 mM MgCl2 to the electrophoresis buffer to stabilise DNA interactions.

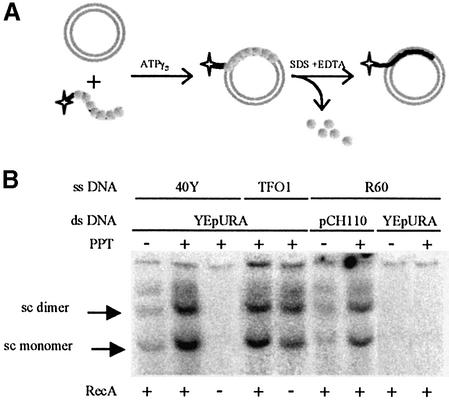

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic representation of the D-loop assay. (B) Joint molecules were formed between short oligonucleotides (40Y2, TFO1 and R60) and target duplex plasmids (YEpURA and pCH110) with and without the PPT sequence. Nucleoprotein filaments were formed by incubating 0.5 µM oligonucleotides with 7 µM RecA protein or no RecA protein. The arrows indicate the positions to which the supercoiled forms of the plasmids migrate.

Two plasmids were used as targets. The YEpURA-PPT plasmid carries a PPT sequence starting 2 nt away from the sequence homologous to the 40Y2 oligonucleotide. The YEpURA plasmid is identical to YEpURA-PPT except that it does not contain the PPT insert. Both plasmids were incubated with the labelled 40Y2 oligonucleotide and complex formation was assessed by quantifying the labelled oligonucleotides migrating with the plasmids. Plasmid concentration and migration were checked by ethidium bromide staining before radioactivity analysis. If a ratio of one RecA monomer to three nucleotides was used, five times more complexes were formed with YEpURA-PPT than with YEpURA (Fig. 2B). We investigated whether this was due to the presence of the PPT sequence by repeating the assay with pCH110-PPT, which contains a polypurine·polypyrimidine sequence different from that of YEpURA-PPT (see Materials and Methods). The abilities of the two PPT sequences to form triple helices with TFOs have been compared, and no significant differences were observed (unpublished data). We compared the complex formation abilities of pCH110-PPT and pCH110, using the R60 oligonucleotide, which targets a sequence in the vicinity of the PPT. As for the YEpURA plasmids, pCH110-PPT formed considerably more complexes than pCH110 (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that complex formation is more efficient in the presence of polypurine·polypyrimidine sequences and does not depend on the plasmid carrying these sequences or on the specific sequence of the PPT.

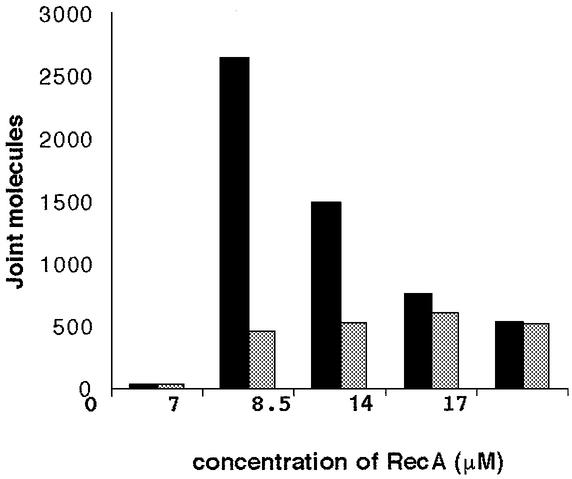

The stimulation of complex formation by PPT sequences is inhibited by excess RecA

To investigate the mechanism involved in the formation of complexes between PPT sequences and duplex DNA, we investigated the effects of various concentrations of RecA on the formation of joint molecules. As expected, no joint molecules were detected in the absence of RecA (Fig. 2B). Thus, the formation of joint molecules with YEpURA-PPT requires the RecA protein. We used four different concentrations of RecA, corresponding to nucleotide/RecA monomer ratios of 3:1, 2.5:1, 1.5:1 and 1:1. RecA protein concentration did not affect the formation of D-loops in the absence of the PPT sequence. Surprisingly, the stimulatory effect of PPT decreased with increasing RecA concentration (Fig. 3). If the protein/nucleotide ratio was 1:1, the efficiency of complex formation was similar in the presence and absence of PPT. Similar results were obtained with the R60 oligonucleotide, pCH110-PPT and pCH110 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

We assessed the number of joint molecules formed between the 40Y2 oligonucleotide and the YEpURA plasmid (black) or the YEpURA-PPT plasmid (grey). Reactions were performed with 0.5 µM oligonucleotides and various concentrations of RecA: 0, 7, 8.5, 14 and 17 µM. The values indicated on the y-axis are arbitrary units, obtained by phosphorimager analysis. All the measurements were made on the same gel.

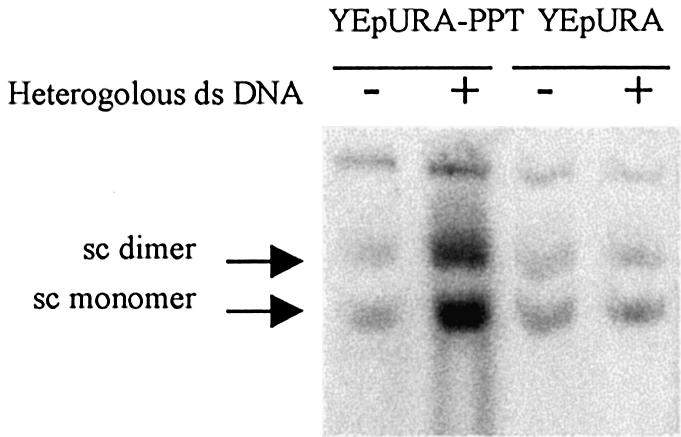

In the cell, oligonucleotides recombine with chromosomal DNA, whereas non-homologous duplex DNA is present in a huge excess over the homologous target. To mimic this situation, we assessed D-loop formation after adding heterologous duplex DNA. A supercoiled plasmid was added to the reaction to compete with the target sequence, thereby decreasing the percentage of the target sequence from 0.5 to 0.05% of the total duplex DNA present in the reaction mixture. The addition of heterologous DNA did not affect the formation of complexes with the YEpURA plasmid. It has been reported that the dilution of a homologous sequence with up to a 200 000-fold excess of heterologous DNA does not affect the efficiency of D-loop formation with long ssDNA (15). In contrast, for D-loops formed with the YEpURA-PPT plasmid, adding heterologous DNA duplex strongly stimulated the formation of joint molecules (Fig. 4). This stimulation was observed even if the heterologous DNA was present in 25 000-fold excess over the target sequence. We checked that sequence context and supercoiling of the heterologous DNA did not affect the formation of joint molecules with YEpURA-PPT. Previous assays used the supercoiled plasmid pUC19 as the heterologous competitor DNA. We tested the effect of similar amounts of other heterologous DNAs: the YEpLEU plasmid, the replicative form of M13 phage and a linear fragment of DNA (2962 bp) generated by amplifying a phage λ chromosome. In all cases, the addition of heterologous DNA stimulated joint molecule formation with YEpURA-PPT and had little effect on complex formation with YEpURA (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Joint molecules were formed by incubating 0.5 µM oligonucleotides and 17 µM RecA with a 0.01 µM solution of plasmid molecules. Where indicated, 5 µg of heterologous DNA was added to the reaction, increasing total DNA concentration by a factor of 10.

Excess RecA does not prevent the formation of triple helix at a PPT locus

As the PPT can form a triple helix upon binding of a TFO, we tested the effect of excess RecA on oligonucleotide-directed triple helix formation between TFO1 and YEpURA-PPT. Consistent with previous reports (6), we found that the TFO1 formed a triple helix with YEpURA-PPT in the presence and absence of RecA. Triple helix formation was not affected by the concentration of RecA (Fig. 2B) or by the addition of heterologous DNA. Thus, excess RecA does not prevent PPT from stimulating the formation of D-loops by altering the triple helix-forming properties of the PPT sequence. Moreover, as many joint molecules formed between the YEpURA-PPT plasmid and the 40Y oligonucleotide as triplex joints formed between YEpURA-PPT and a TFO1 oligonucleotide (Fig. 2B).

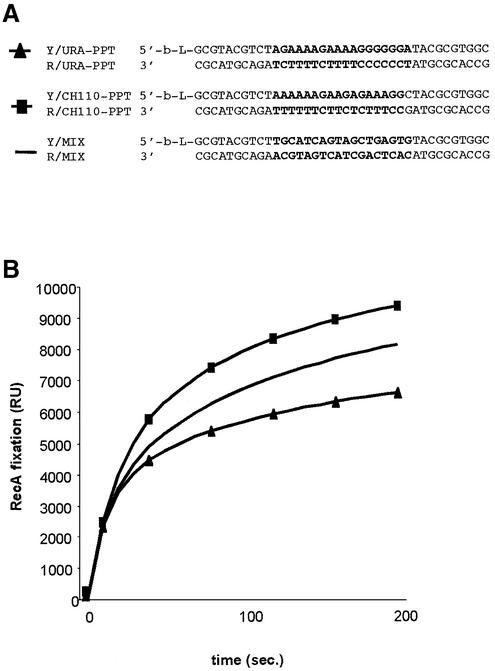

RecA does not preferentially bind to PPT sequences

We previously demonstrated that the affinity of RecA for ssDNAs depends on the sequence of the DNA used (16). We used a technique based on the detection of surface plasmon resonance (BIAcore) to compare the kinetics of RecA binding to PPT duplex sequences and random sequences. The concentration of immobilised biotinylated oligonucleotides (38 bp) and was determined by assessing binding of the single strand binding (SSB) protein, as described previously (16). Complementary oligonucleotides were annealed to the bound sequences and various concentrations of RecA were injected. We then followed the binding kinetics in real time. The only differences in the sequences were in the central 18 bp, corresponding to the PPT sequences of YEpURA-PPT and pCH110-PPT. Although the kinetics of association and dissociation of the protein with the PPT sequence and the two random control sequences were not similar, there was no clear evidence that RecA preferentially bound to a short duplex DNA with a PPT sequence (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Sequences of the duplex DNA bound on the surface (-b-L-: biotinylated cytosine). (B) Binding of RecA to the three duplex sequences. The RU are directly correlated with the concentration of molecules in the surface layer (1 RU = 1 pg/mm2). Flowcell surfaces were bound with 800 RU duplex DNA corresponding to 0.8 ng/mm2 and we injected 2 µM RecA.

The stimulatory effect of the PPT sequence is not local

In the experiments described above, the PPT sequence was located 2 bp downstream from the target sequence. We assessed the formation of complexes between YEpURA-PPT and homologous oligonucleotide targeting sequences located at various positions with respect to the PPT: 3 bp upstream from the PPT and 43, 83, 123, 382 and 3460 bp downstream from the PPT (Fig. 1). All of these sequences are present on the YEpURA plasmid and were tested in parallel with YEpURA-PPT and YEpURA, to determine the specific effect of the PPT sequence. The addition of heterologous DNA stimulated the formation of joint molecules at the various positions in YEpURA-PPT, by a factor of five to eight. No stimulatory effect was observed for complexes formed with the YEpURA plasmid at any position. However, if the heterologous DNA was pCH110-PPT, which carries a PPT sequence, then the formation of complexes with YEpURA was stimulated, indicating that the PPT sequence may also act in trans in this assay (data not shown).

The PPT sequence stimulates gene targeting in vivo

We investigated the effect of the PPT sequence on the correction of a mutation, an AG dinucleotide insertion, in the URA3 gene of S.cerevisiae. No spontaneous reversion of this mutation was observed during our experiments. To correct the mutation, we used the EB34 oligonucleotide carrying the 40Y sequence with the modification introduced via the HindIII construct, but not the AG insertion. The mutation to correct was 23 bp from the end of the PPT sequence. Two strains (ORT3453 and ORT3458) were co-transformed with the EB34 oligonucleotide and a replication-competent plasmid (pLeu). The efficiency of transfection was estimated from the number of LEU+ clones. The efficiency of gene correction was estimated as the ratio of corrected URA+ cells divided by the number of transfected LEU+ cells. The experiments were repeated four times and inter-experiment variability was very low. The mean frequency of gene correction was 0.017 in the ORT3453 strain, which contains the PPT, and 0.002 in ORT 3458, which does not. Thus, the presence of the PPT sequence increased the level of targeted gene correction by a factor of eight.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the effects of a PPT on the pairing of homologous DNAs, focusing on two related issues. First, there is considerable evidence to suggest that RecA nucleoprotein filaments target short oligonucleotides to their complementary sequences on large duplex DNA molecules. We investigated whether this reaction was affected by the presence of a PPT sequence on the targeted duplex. Secondly, we characterised the mechanism involved in the stimulation of D-loop formation by the PPT sequence, with various substrate sequences and reaction conditions.

We found that the presence of a PPT sequence on the target duplex stimulated the formation of joint molecules between the large duplex DNA and a short homologous oligonucleotide, regardless of their sequences. As two different PPT sequences carried by different duplexes had similar stimulatory effects, these effects are unlikely to be sequence specific. Polypurine·polypyrimidine sequences have special physicochemical properties facilitating the formation of triple helices. Indeed, in the presence of magnesium ions, a 30 bp poly(dG)-poly(dC) sequence can form an intramolecular triple-helical structure (H-DNA) (17). These structures contain a triplex and a displaced ssDNA corresponding to the fourth strand, which is not involved in triplex formation. Similar structures can also be generated from two duplex molecules carrying PPT sequences (18). Hampel et al. (19) described plasmid dimerisation mediated by the formation of a triplex between two linear DNAs carrying PPT sequences.

When coated with RecA, ssDNA molecules form large aggregates with naked duplex DNA, regardless of their sequences (12). A variety of conditions that increase or inhibit aggregation also affect homologous pairing (20). By adding various amounts of homologous ssDNA, Honigberg et al. demonstrated that RecA nucleoprotein filaments mostly search neighbouring duplex molecules (15). With short ssDNA, aggregation becomes limiting. Low pairing efficiency may therefore be due to a lack of large aggregates. The PPT sequences that interact with other duplex DNA sequences may be involved in DNA aggregation in the presence of RecA. Electron microscopy showed that plasmids with PPT sequences form large aggregates (unpublished results). The addition of RecA increased the size and the number of aggregates. However, it was not possible to investigate the organisation of the molecules within the aggregates. Goobes et al. observed unique patterns of condensation between short DNAs carrying PPT sequences (21). They accounted for this tendency to self-assemble by the presence of strong attractive interactions resulting from enhanced ion correlations.

Excess RecA inhibits the stimulation of joint molecule formation by the PPT sequence. In the presence of high concentrations of RecA, corresponding to conditions in which joint molecules are formed equally efficiently in the presence and absence of PPT, RecA monomers are present in 2.5-fold excess with respect to the minimal concentration required to cover all the oligonucleotides completely. Excess RecA does not affect joint molecule formation in the absence of a PPT sequence and no inhibitory effects have been reported in previous studies in similar experimental conditions (7). The analysis of RecA binding to short duplex DNA molecules showed that RecA does not preferentially bind to PPT sequences. However, it is highly unlikely that specific DNA structures induced by the PPT sequence were formed on short duplex DNA molecules. This rate-limiting structural transition may involve the transient local denaturation of dsDNA, resulting in ssDNA that is efficiently bound by RecA (22). The addition to duplex DNA of a ssDNA tail or a ssDNA gap strongly stimulates RecA binding (23). We suggest that the PPT sequence locally denatures the duplex DNA, thereby acting as a nucleation locus for the loading of RecA (24). This would account for the observation that excess RecA had an inhibitory effect only in the presence of a PPT sequence. The addition of heteroduplex DNA restored PPT-dependent stimulation in the presence of high concentrations of RecA. The simplest hypothesis is that the duplex DNA traps the excess RecA. High concentrations of RecA may prevent the formation of aggregates, by inactivating the PPT region. In these conditions, few complexes would be formed in the presence of the PPT plasmid, as with the control plasmid, which does not contain a PPT sequence. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the excess of free RecA proteins changes the environmental conditions required for PPT sequence self-assembly. The self-assembly of PPT sequences has been shown to be very sensitive to salt concentrations and spermine (21). The aggregation model is attractive as it explains why stimulation was almost as efficient in the vicinity of the PPT sequence as at a distant position on the plasmid. The concentration of plasmids in the aggregates should increase the density of target sequences, regardless of their position on the plasmid.

In conclusion, our data suggest that PPT sequences stimulate complex formation via the aggregation of duplex DNA in a network facilitating homology searches by short nucleoprotein filaments. It is unclear how such properties affect recombination in vivo. An unequal sister chromatid exchange locus in a mouse myeloma cell line has been reported to contain a PPT sequence (25). Friedreich’s ataxia, a degenerative human disease, is associated with very large expanses of a PPT sequence composed of GAA repeats (26). Although the mechanism involved is unclear, unequal recombination may be responsible for the unstable nature of this sequence. In very similar experimental conditions, we have shown that the PPT-dependent stimulation of joint molecule formation, as observed in vitro, increases recombination in vivo. Our results suggest that, in vivo, PPT sequences may exert their effect through local secondary structure modifications. A recent study reported the detection of triplex DNA molecules on the chromosomes of living human cells and suggested that these molecules may be involved in the spatial association of chromosomes (27). Thus, even very short motifs may significantly affect the packaging state of the genome and modulate general DNA processes.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank M. Pierre and N. Thiercelin for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from CNRS ‘Programme Physique et Chimie du Vivant’ (97-178), the ‘Programme Incitatif Collaboratif’ from Institut Curie and the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. E.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunzelmann K., Legendre,J.Y., Knoell,D.L., Escobar,L.C., Xu,Z. and Gruenert,D.C. (1996) Gene targeting of CFTR DNA in CF epithelial cells. Gene Ther., 3, 859–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole-Strauss A., Yoon,K., Xiang,Y., Byrne,B.C., Rice,M.C., Gryn,J., Holloman,W.K. and Kmiec,E.B. (1996) Correction of the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia by an RNA-DNA oligonucleotide. Science, 273, 1386–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan P.P. and Glazer,P.M. (1997) Triplex DNA: fundamentals, advances, and potential applications for gene therapy. J. Mol. Med., 75, 267–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan P.P., Lin,M., Faruqi,A.F., Powell,J., Seidman,M.M. and Glazer,P.M. (1999) Targeted correction of an episomal gene in mammalian cells by a short DNA fragment tethered to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 11541–11548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culver K.W., Hsieh,W.T., Huyen,Y., Chen,V., Liu,J., Khripine,Y. and Khorlin,A. (1999) Correction of chromosomal point mutations in human cells with bifunctional oligonucleotides. Nat. Biotechnol., 17, 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biet E., Maurisse,R., Dutreix,M. and Sun,J. (2001) Stimulation of RecA-mediated D-loop formation by oligonucleotide-directed triple-helix formation: guided homologous recombination (GOREC). Biochemistry, 40, 1779–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh P., Camerini-Otero,C.S. and Camerini-Otero,R.D. (1992) The synapsis event in the homologous pairing of DNAs: RecA recognizes and pairs less than one helical repeat of DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 6492–6496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holliday R. (1974) Molecular aspects of genetic exchange and gene conversion. Genetics, 78, 273–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meselson M.S. and Radding,C.M. (1975) A general model for genetic recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 72, 358–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szostak J.W., Orr-Weaver,T.L., Rothstein,R.J. and Stahl,F.W. (1983) The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell, 33, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leahy M.C. and Radding,C.M. (1986) Topography of the interaction of recA protein with single-stranded deoxyoligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 6954–6960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsang S.S., Muniyappa,K., Azhderian,E., Gonda,D.K., Radding,C.M., Flory,J. and Chase,J.W. (1985) Intermediates in homologous pairing promoted by recA protein. Isolation and characterization of active presynaptic complexes. J. Mol. Biol., 185, 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knauert M.P. and Glazer,P.M. (2001) Triplex forming oligonucleotides: sequence-specific tools for gene targeting. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 2243–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantor C.R., Warshaw,M.M. and Shapiro,H. (1970) Oligonucleotide interactions. 3. Circular dichroism studies of the conformation of deoxyoligonucleotides. Biopolymers, 9, 1059–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honigberg S.M., Rao,B.J. and Radding,C.M. (1986) Ability of RecA protein to promote a search for rare sequences in duplex DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 9586–9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biet E., Sun,J.-S. and Dutreix,M. (1999) Conserved sequence preference in DNA binding among recombination proteins: an effect of ssDNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohwi Y. and Kohwi-Shigematsu,T. (1988) Magnesium ion-dependent triple-helix structure formed by homopurine-homopyrimidine sequences in supercoiled plasmid DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 3781–3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen D. and Gilbert,W. (1988) Formation of parallel four-stranded complexes by guanine-rich motifs in DNA and its implications for meiosis. Nature, 334, 364–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampel K.J., Burkholder,G.D. and Lee,J.S. (1993) Plasmid dimerization mediated by triplex formation between polypyrimidine-polypurine repeats. Biochemistry, 32, 1072–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow S.A. and Radding,C.M. (1985) Ionic inhibition of formation of RecA nucleoprotein networks blocks homologous pairing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 5646–5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goobes R., Cohen,O. and Minsky,A. (2002) Unique condensation patterns of triplex DNA: physical aspects and physiological implications. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 2154–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowalczykowski S.C., Clow,J. and Krupp,R.A. (1987) Properties of the duplex DNA-dependent ATPase activity of Escherichia coli RecA protein and its role in branch migration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 3127–3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaner S.L. and Radding,C.M. (1987) Translocation of Escherichia coli recA protein from a single-stranded tail to contiguous duplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 9211–9219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leger J.F., Robert,J., Bourdieu,L., Chatenay,D. and Marko,J.F. (1998) RecA binding to a single double-stranded DNA molecule: a possible role of DNA conformational fluctuations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 12295–12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinreb A., Collier,D.A., Birshtein,B.K. and Wells,R.D. (1990) Left-handed Z-DNA and intramolecular triplex formation at the site of an unequal sister chromatid exchange. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 1352–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campuzano V., Montermini,L., Molto,M.D., Pianese,L., Cossee,M., Cavalcanti,F., Monros,E., Rodius,F., Duclos,F., Monticelli,A. et al. (1996) Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science, 271, 1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno M., Fukagawa,T., Lee,J.S. and Ikemura,T. (2002) Triplex-forming DNAs in the human interphase nucleus visualized in situ by polypurine/polypyrimidine DNA probes and antitriplex antibodies. Chromosoma, 111, 201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]