Abstract

The polymorphism of a new microsatellite locus (CAI) was investigated in a total of 114 Candida albicans strains, including 73 independent clinical isolates, multiple isolates from the same patient, isolates from several episodes of recurrent vulvovaginal infections, and two reference strains. PCR genotyping was performed automatically, using a fluorescence-labeled primer, and in the 73 independent isolates, 26 alleles and 44 different genotypes were identified, resulting in a discriminatory power of 0.97. CAI was revealed to be species specific and showed a low mutation rate, since no amplification product was obtained when testing other pathogenic Candida species and no genotype differences were observed when testing over 300 generations. When applying this microsatellite to the identification of strains isolated from recurrent vulvovaginal infections in eight patients, it was found that 13 out of 15 episodes were due to the same strain. When multiple isolates, obtained from the same patient and plated simultaneously, were typed for CAI, the same genotype was found in each case, confirming that the infecting population was clonal. Moreover, the same genotype appeared in isolates from the rectum and the vagina, revealing that the former could be a reservoir of potentially pathogenic strains. This new microsatellite proves to be a valuable tool to differentiate C. albicans strains. Furthermore, when compared to other molecular genotyping techniques, CAI proved to be very simple, highly efficient, and reproducible, being suitable for low-quantity and very-degraded samples and for application in large-scale epidemiological studies.

It is known that opportunistic yeast pathogens are common residents of the mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary system, and oral cavity in warm-blooded animals. Although several yeast species can be associated with infection, the predominant causal agent of candidiasis is Candida albicans. This yeast causes several infections in humans, including a wide variety of life-threatening conditions triggered by bloodstream infections, especially in immunocompromised patients. Since pathogenicity and antifungal susceptibility often vary among strains, a rapid and accurate identification of the disease-causing strains of C. albicans is crucial for clinical treatment and epidemiological studies.

Advances in molecular biology in the last 2 decades have allowed the development of rapid molecular genotyping techniques for clinical and epidemiological analysis. Several molecular typing methods have been developed to differentiate C. albicans strains, including electrophoretic karyotyping (2), the use of species-specific probes such as Ca3 or 27A in restriction enzyme analysis (20, 23, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35), and PCR-based methods (1, 10, 21, 24, 28, 37). More recently, short tandem repeats (STRs) or microsatellites have assumed increasing importance as molecular markers in fields so diverse as oncogenetics, population genetics, and strain identification and characterization. They occur in several thousands of copies dispersed throughout the genome and display high polymorphism, Mendelian codominant inheritance, and PCR typing simplicity. Only a few polymorphic microsatellite loci have been identified so far in the C. albicans genome, most of them located near or inside coding regions and exhibiting a discriminatory power between 0.77 and 0.91 (3, 4, 7, 19, 25). However, it is known that the degree of polymorphism is much higher in microsatellite loci from noncoding regions, and to date, few studies have been developed for the analysis of loci from those regions in C. albicans (18, 19).

The aim of this work was to identify and describe a new highly informative microsatellite locus (CAI), outside a known coding region, in the genome of the pathogenic yeast C. albicans and evaluate its applicability to accurately differentiate strains. Another goal of this study was to use this microsatellite marker to assess the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates obtained from sequential episodes of recurrent vaginal candidosis and from multiple simultaneous isolations from the same patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microsatellite selection and design of PCR primers.

A search in C. albicans genome sequences, available in databases from Stanford's DNA Sequencing and Technology Center (http://www.sequence.stanford.edu/group/candida), was conducted for sequences containing microsatellite repeats. The aim of this search was to select repetitive sequences that were expected to have a very high degree of polymorphism, based on two criteria: the number of simple repeat units (more than 20) and the location, outside a coding region. Ten microsatellites were selected and primers were designed, in the nonvariable flanking regions, for locus-specific amplification. Based on the results of preliminary studies on amplification efficiency, species specificity, and observed polymorphism, a sequence containing 32 CAA repeats, 396062C04.s1.seq, was selected for further characterization and for application in strain identification purposes.

Yeast strains.

A total of 112 clinical isolates of C. albicans, obtained from two hospitals and a health center located in Braga and Porto (north Portugal), the reference strain WO-1, and the type strain PYCC 3436 (ATCC 18804), were selected for this study. All isolates were previously identified by their assimilation patterns on ID 32C strips (Biomerieux, SA, Marcy-L'Étoile, France) and by PCR fingerprinting with primer T3B using the methodology described by Thanos et al. (37). The type strains of C. parapsilosis PYCC 2545 (ATCC 22019), C. krusei PYCC 3343 (ATCC 6258), C. tropicalis PYCC 3097 (ATCC 750), C. glabrata PYCC 2418 (ATCC 2001), C. guilliermondii PYCC 2730 (ATCC 6260), C. lusitaniae PYCC 2705 (ATCC 34449), and C. dubliniensis CBS 7987 (ATCC MYA-646) were also tested. All reference strains were obtained from the Portuguese Yeast Culture Collection, New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, except the isolates of C. dubliniensis, which were from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands. Stock cultures were maintained on Sabouraud glucose agar medium at 4°C.

DNA isolation and PCR amplification.

Prior to DNA isolation, cells were grown overnight on Sabouraud medium at 30°C. DNA extraction followed procedures previously described (15). PCRs were performed in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 1× PCR buffer (20 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl), a 0.2 mM concentration of each of four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega), a 0.25 μM concentration of each primer (forward, 5′-ATG CCA TTG AGT GGA ATT GG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGT GGC TTG TGT TGG GTT TT-3′), 25 ng of genomic DNA, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco). For automatic allele size determination, the forward primer was 5′ fluorescently labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein.

Amplification was carried out in a DNA thermocycler (model 2400; AB Applied Biosystems) with a program consisting of an initial denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C.

Fragment size determination.

For allele size determination, the PCR products were run in an ABI 310 genetic analyzer (AB Applied Biosystems). Fragment sizes were determined automatically using the GeneScan 3.1 Analysis software. Alleles have been designated according to the number of trinucleotide repeats (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Frequency of genotypes identified for CAI microsatellite

| Observed genotype | No. of strains | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 11-18 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 11-28 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 13-32 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 16-27 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 17-17 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 17-21 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 17-23 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 18-18 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 18-25 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 18-27 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 18-34 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 18-47 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 20-20 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 20-27 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 20-28 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 20-37 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 21-21 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 21-22 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 21-25 | 6 | 0.082 |

| 21-26 | 4 | 0.055 |

| 21-27 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 22-22 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 22-23 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 22-34 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 23-24 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 23-27 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 24-24 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 24-26 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 24-27 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 25-25 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 25-26 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 25-27 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 26-26 | 3 | 0.041 |

| 26-33 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 27-27 | 2 | 0.027 |

| 27-42 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 27-45 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 27-47 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 27-49 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 28-28 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 28-47 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 30-30 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 36-36 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 39-46 | 1 | 0.014 |

DNA sequence analysis.

After PCR amplification, DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 6% polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions (6.5 M urea) using the buffer systems described by Gusmão et al. (12) and visualized by the silver staining method (5). Allele bands were cut individually from the gel, eluted in 250 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer, frozen and thawed three times, reamplified, and purified with Microspin S-300 HR columns (Pharmacia). The purified products were subjected to a dideoxy cycle sequencing reaction using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (AB Applied Biosystems). Sequence analysis was performed on an ABI 377 genetic analyzer using the Data Collection Software 377-18.

Stability.

To test the stability of the marker, three different clinical isolates and the type strain were grown in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 500 ml of Sabouraud medium and incubated at 30°C in an orbital shaker (160 rpm). At the end of the exponential phase, a 1/10 dilution with new medium was made in order to allow continuing of cell duplication. This procedure went on for 4 weeks until completion of around 300 generations. Cells were harvested at the end of approximately 100, 200, and 300 generations, and DNA was extracted for amplification.

Reproducibility.

Reproducibility of the method was assessed by testing three strains 10 times in three separate experiments.

Statistical analysis.

Genotype frequencies were estimated by genotype counting. Statistical analysis for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was performed using an exact test (11), running the statistical software package GENEPOP. The discriminatory power of the marker was calculated according to the method of Hunter and Gaston (14).

RESULTS

With the aim of identifying highly informative microsatellite polymorphisms for molecular discrimination of C. albicans, a search for short repetitive sequences was conducted as described in Materials ands Methods. It is well established that a higher degree of polymorphism is expected for microsatellites outside coding regions (26) as well as for long tracts of simple repeats (34). For these reasons, our search was based upon the number of uninterrupted repeats outside known coding regions. Dinucleotide repeats were not considered, since they are described as being more prone to stutter bands due to DNA polymerase slippage during amplification (9).

For the 10 sequences selected with more than 20 uninterrupted tri- to pentanucleotide repeat units, specific primers were designed, for annealing in the nonvariable flanking regions, and used for preliminary studies on amplification efficiency and specificity and for evaluation of the informative content of polymorphism. Only a sequence containing 32 CAA units showed the required characteristics and was selected for further studies and to address the question of applicability in the differentiation of related strains. This new microsatellite locus was designated CAI.

Sequence analysis.

Sequencing analysis of 37 amplified fragments revealed that the consensus structure was in accordance with that originally published (396062C04.s1.seq), confirming locus-specific amplification and structure of the alleles. The variation in length of the CAI alleles was always due to differences in the number of trinucleotide repeat units, and therefore, the alleles were designated by the total number of trinucleotide repeats. For instance, allele 21 was given this designation when it was shown to be of a size consistent with that number of repetitions independently of the structure variation. The sequence analysis revealed three different levels of polymorphism in CAI, (i) the number of repeats, (ii) the structure of the repeated region, and (iii) point mutations outside the repeated region (data not shown). In the context of this work, the genotyping was done based only on the first level of polymorphism, but the second and third levels of variation may contribute to further differentiation of C. albicans strains.

CAI locus analysis.

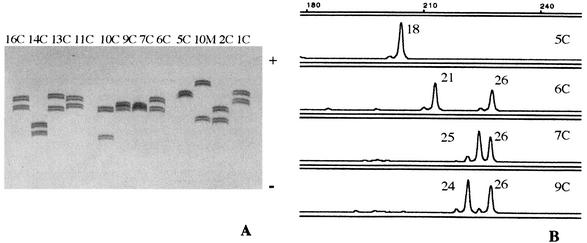

One hundred and twelve clinical isolates of C. albicans and two reference strains were genotyped for CAI (examples shown in Fig. 1A). For an easier and more accurate size determination, genotype analysis was performed automatically using a fluorescent labeled primer (Fig. 1B). In order to check for method reproducibility, for each of four selected samples, the PCR was performed at least 10 different times (including different DNA extractions), always displaying the same result.

FIG. 1.

(A) Denaturing gel electrophoresis of the fragments obtained by PCR of 12 C. albicans clinical isolates for CAI marker. (B) GeneScan profiles corresponding to four of the strains shown in panel A, depicting the results of automatic fragment sizing.

The PCR products obtained consisted of fragments with different lengths, varying between 189 bp (11 repeats) and 303 bp (49 repeats). Since C. albicans is thought to be diploid, each fragment was assigned to an allele and the strains showing two PCR products were typed as heterozygous (72.6%), while when a single amplification product was detected they were considered to be homozygous.

Using the results obtained for the sample of 73 nonrelated strains, isolated from nonrelated patients, a significant departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium expectations was found (P < 0.001). This finding supports the previous conclusions (10, 17) that the inheritance in C. albicans is mainly clonal. For this reason, the CAI diversity content and discriminatory power can only be evaluated using genotype frequencies rather than allele frequencies. In the 73 nonrelated strains, a total of 26 different alleles and 44 distinct genotypes were observed. The genotype frequencies vary between 0.014 and 0.082. The most frequent genotype (21-25) was present in only 6 out of the 73 nonrelated strains (Table 1). The number of CAI genotypes is much higher than the ones described so far for other loci (3, 4, 6, 7, 13, 18, 19, 25, 34), resulting in a discriminatory power of 0.97.

Stability and specificity.

In vitro stability of the CAI marker was tested by growing four independent strains over 300 generations. For all the strains tested the genotypes were the same after these generations, suggesting that CAI has an expected mutation rate less than 3.33 × 10−3.

The CAI microsatellite also appeared to be species specific, since no amplification products were obtained when using the described primers in the amplification of other pathogenic Candida species, namely, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. guilliermondii, C. lusitaniae, and C. dubliniensis (data not shown). It is noteworthy to mention that the CAI microsatellite was absent in C. dubliniensis, which is very closely related to C. albicans and only very recently was recognized as a different species (36).

Similar results were found in previously described STRs, by testing other Candida species: C. krusei, (7), C. tropicalis and C. glabrata (4), and C. dubliniensis (25).

The use of CAI for strain distinction.

CAI genotyping results obtained in eight cases of multiple isolates from the same patient and plated at the same time are shown in Table 2. As can be observed, in each case, all the strains isolated showed exactly the same genotype, suggesting that only one strain is present in the infecting population.

TABLE 2.

Multiple strains isolated from the same patient and cultured simultaneouslya

| Patient | Isolate | Body location or specimen | CAI genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1M | Urine | 21-25 |

| 2M | Urine | 21-25 | |

| 31M | Urine | 21-25 | |

| B | 4M | Peritoneal exudate | 26-26 |

| 15M | Peritoneal exudate | 26-26 | |

| 17M | Peritoneal exudate | 26-26 | |

| 19M | Peritoneal exudate | 26-26 | |

| C | 10M | Upper respiratory tract | 17-17 |

| 12M | Upper respiratory tract | 17-17 | |

| D | 52M | Urine | 21-21 |

| 55M | Urine | 21-21 | |

| E | 41M | Urine | 21-22 |

| 43M | Urine | 21-22 | |

| 45M | Urine | 21-22 | |

| 47M | Urine | 21-22 | |

| 48M | Urine | 21-22 | |

| F | 82M | Urine | 18-47 |

| 84M | Urine | 18-47 | |

| G | 49M | Urine | 36-36 |

| 51M | Urine | 36-36 | |

| H | 69M | Upper respiratory tract | 21-25 |

| 75M | Upper respiratory tract | 21-25 | |

| 86M | Upper respiratory tract | 21-25 | |

| I | 64M | Upper respiratory tract | 22-22 |

| 67M | Upper respiratory tract | 22-22 | |

| 88M | Urine | 20-28 | |

| J | 33M | Vagina | 23-24 |

| 37M | Urine | 17-23 |

Each patient is referred by a letter (A to J), and the isolates are distinguished by a number followed by an M (laboratory designation).

To verify whether the infecting population is the same at different body locations, multiple isolates were taken from the patients displaying multiple local infections. The results showed that two strains from patient I, isolated from the upper respiratory tract, were identical, although different from the urine isolate. The same occurred for patient J, where distinct genotypes were observed for the two strains isolated, one from the vagina and the other from urine. These results show clearly that in different body sites, patients can harbor distinct clones but the infecting population at each body site is monoclonal.

The analysis of 15 cases of recurrent vulvovaginal infections in eight patients revealed that the infecting C. albicans strains isolated sequentially at different relapses displayed the same CAI genotype, except in two cases (Table 3). The second and third isolates from patients L and N presented a different genotype from isolates from the first episode, indicating possible cases of strain replacement. However, further analysis with three additional STRs, including the one described by Bretagne et al., EF3 (4), confirmed that all three L isolates had the same genotype (data not shown). Thus, most probably, they do not represent different strains and just differ by a mutation at CAI locus. The microvariation observed inside one of the alleles, from 30 to 32 repetitions, shows a different scenario of recurrent vaginitis with maintenance of a strain which is undergoing microevolution that might have been induced by antifungal treatment. For patient N, a true case of strain replacement really occurred, which was confirmed with further analysis using the same additional STRs (results not shown). These observations are in accordance with the literature (16), where three basic scenarios are described for the genetic relatedness of strains isolated from patients with recurrent vaginitis: (i) maintenance of the same strain, (ii) maintenance of a strain which is undergoing microevolution, and (iii) strain replacement.

TABLE 3.

CAI genotypes of sequential isolates from vulvovaginal recurrent infections and anorectal or vulvovaginal body locationsa

| Strain category and patient | Isolate | CAI genotype |

|---|---|---|

| Recurrent | ||

| K | 3J | 17-23 |

| 4J | 17-23 | |

| 5J | 17-23 | |

| 6J | 17-23 | |

| L | 7J | 30-30 |

| 8J | 30-32 | |

| 9J | 30-32 | |

| M | 12J | 18-25 |

| 13J | 18-25 | |

| 14J | 18-25 | |

| 15J | 18-25 | |

| 16J | 18-25 | |

| N | 17J | 21-21 |

| 18J | 20-29 | |

| 19J | 20-29 | |

| O | 20J | 26-26 |

| 21J | 26-26 | |

| P | 22J | 23-27 |

| 23J | 23-27 | |

| Q | 27J | 22-23 |

| 28J | 22-23 | |

| S | 29J | 20-20 |

| 30J | 20-20 | |

| Vagina or rectum | ||

| T | 31J-V | 21-26 |

| 32J-R | 21-26 | |

| U | 35J-V | 25-25 |

| 36J-R | 25-25 | |

| V | 37J-V | 18-27 |

| 38J-R | 18-27 | |

| X | 39J-V | 21-22 |

| 40J-R | 21-22 | |

| Z | 41J-Ra | 23-27 |

| 42J-Rb | 23-27 | |

| 43J-V | 23-27 |

Each patient is referred to by a letter (K to Z), and the isolates are distinguished by a number followed by a J (laboratory designation). An additional letter was added to designations for strains from the vagina (V) or rectum (R).

In five patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis, anorectal and vulvovaginal isolates were simultaneously obtained and typed with CAI (results in Table 3). In all cases, the strains shared the same genotype, confirming that the anorectal region might represent a reservoir of C. albicans infecting strains, in accordance with previous observations (16, 31, 33).

DISCUSSION

Many investigations were undertaken in order to search for molecular variation in the genome of C. albicans for a large set of applications, such as identification, phylogenetic analysis, resistance development, and gene association studies (4, 17, 25). As referred to in the introduction, nowadays there are different DNA-based methodologies available for these purposes. It has been demonstrated that STR-PCR-based methods have several advantages over the other methodologies used in strain identification, since microsatellites are known to be highly polymorphic, the PCR is a less time-consuming technique, and results can be easily reproduced and compared between laboratories (4, 6).

Numerous microsatellites have been reported in various organisms (8, 13, 34, 38), but until now, only a few polymorphic microsatellite loci were described in C. albicans, most of them located near (EF3 [4], CDC3, and HIS3 [3]) or inside (ERK1, 2NF1, CCN2, CPH2, and EFG1 [25]) coding regions. The discriminatory power calculated for these STRs was between 0.77 (for CDC3) and 0.91 (for HIS3), and the most discriminant microsatellite approach was obtained when combining three STRs in a single multiplex amplification reaction, yielding a discriminatory power of 0.97 (3), the same obtained for CAI in the present work. Thus, CAI appears to be more polymorphic than other STRs described for C. albicans. This result confirms the criteria we defined in choosing this microsatellite are robust enough for epidemiological studies. A probable explanation lies in the fact that CAI is, as far as it is now known, probably located in a noncoding region, making it less prone to selective forces (26), and presents a long noninterrupted repetitive tract, as evidenced by its accumulated diversity.

This high degree of polymorphism exhibited by CAI could be correlated with a high mutation rate, which would limit its use in strain identification. However, our results demonstrate that CAI is relatively stable not only in laboratory culture but also in vivo, since in the cases of recurrent infections studied we found the same CAI genotype, with a single exception, suggesting that this marker could be used for epidemiological tracing.

Development of multiplex systems, coamplifying several STRs, in order to test rapidly and reproducibly a great number of isolates, is of great importance in biomedical mycology. CAI and EF3 STRs clearly stand out as candidates to be included in such a multiplex system since they are very well characterized and the same typing methodology is used. Special care must be paid to typing standardization, since the use of different primers or separation techniques has been shown to produce different results from the same locus, preventing their comparison in parallel. Standardization of allele nomenclature, based on the repeat number rather than fragment size, is also essential for the construction of public databases in light of what is already in current use in human genetics (22, 30).

It is clear that the analysis of multiple STR loci may enable high-speed typing in the near future. The number of currently available markers allows a selection of the best markers, based on typing performance, mutation rates, and discriminative power, to be included in multiplex tests. Furthermore, they can be used to complement other molecular studies such as random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis and DNA fingerprinting to distinguish evolutionarily related strains and define microevolutionary events (4, 25).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) through a multiyear contract with Centro de Ciências do Ambiente (CCA), Universidade do Minho.

We are indebted to Adelaide Alves (Hospital de S. Marcos, Braga) for providing clinical isolates for this study and to Judite Almeida and Alexandra Correia for isolating the strains from Centro de Saúde do Carandá.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barchiesi, F., L. F. Di Francesco, P. Compagnucci, D. Arzeni, O. Cirioni, and G. Scalise. 1997. Genotypic identification of sequential Candida albicans isolates from AIDS patients by polymerase chain reaction techniques. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barchiesi, F., R. J. Hollis, M. Del Poeta, D. A. McGough, G. Scalise, M. G. Rinaldi, and M. A. Pfaller. 1995. Transmission of fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans between patients with AIDS and oropharyngeal candidiasis documented by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21:561-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botterel, F., C. Cesterke, C. Costa, and S. Bretagne. 2001. Analysis of microsatellite markers of Candida albicans used for rapid typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4076-4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretagne, S., J. M. Costa, C. Besmond, R. Carsique, and R. Calderone. 1997. Microsatellite polymorphism in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 gene of Candida albicans as the basis for a typing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1777-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budowle, B., R. Chakraborty, A. M. Giusti, A. J. Eisenberg, and R. C. Allen. 1991. Analysis of the VNRT locus D1S80 by the PCR followed by high resolution PAGE. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 48:137-144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalle, F., N. Franco, J. Lopez, O. Vagner, D. Caillot, P. Chavanet, B. Cuisenier, S. Aho, S., Lizard, and A. Bonnin. 2000. Comparative genotyping of Candida albicans bloodstream and nonbloodstream isolates at a polymorphic microsatellite locus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4554-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field, D., L. Eggert, D. Metzgar, R. Rose, and C. Wills. 1996. Use of polymorphic short and clustered coding-region microsatellites to distinguish strains of Candida albicans. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 15:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field, D., and C. Wills. 1996. Long polymorphic microsatellite in simple organisms. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 263:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gendrel, C.-G., and M. Dutreix. 2001. (GA/TG) Microsatellite sequences escape the inhibition of recombination by mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159:1539-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graser, Y., M. Volovsek, J. Arrington, G. Schonian, W. Presber, T. G. Mitchell, and R. Vilgalys. 1996. Molecular markers reveal the population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:12473-12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo, S. W., and E. A. Thompson. 1992. Performing the exact test of Hardy-Weinberg proportions for multiple alleles. Biometrics 48:361-372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gusmão, L., M. J. Prata, A. Amorim, F. Silva, and I. Bessa. 1997. Characterisation of four short tandem repeat loci (TH01, VWA31/A, CD4 and TP53) in Northern Portugal. Hum. Biol. 69:31-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennequin, C., A. Thierry, G. F. Richard, G. Lecointre, H. V. Nguyen, C. Gaillardin, and B. Dujon. 2001. Microsatellite typing as a new tool for identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:551-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson′s index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser, C., S. Michaelis, and A. Mitchell. 1994. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y.

- 16.Lockhart, S. R., B. D. Reed, C. L. Pierson, and D. R. Soll. 1996. Most frequent scenario for recurrent Candida vaginitis is strain maintenance with “sub shuffling”: demonstration by sequential DNA fingerprinting with probes Ca3, C1, and CARE2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:767-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lott, T. J., B. P. Holloway, D. A. Logan, R. Fundyga, and J. Arnold. 1999. Towards understanding the evolution of the human commensal yeast Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:1137-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lott, T. J., and M. M. Effat. 2001. Evidence for a more recently evolved clade within a Candida albicans North American population. Microbiology 147:1687-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunel, F. V., L. Licciardello, S. Stefani, H. A. Verbrugh, W. J. Melchers, J. F. Meis, S. Scherer, and A. van Belkum. 1998. Lack of consistent short sequence repeat polymorphisms in genetically homologous colonizing and invasive Candida albicans strains. J. Bacteriol. 180:3771-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magee, B. B., T. M. Souza, P. T. Magee. 1987. Strain and species identification by restriction length polymorphism in the ribosomal DNA repeats of Candida species. J. Bacteriol. 169:1639-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mannarelli, B. M., and C. P. Kurtzman. 1998. Rapid identification of Candida albicans and other human pathogenic yeasts by using short oligonucleotides in a PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1634-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, P. D., H. Schmitter, and P. M. Schneider. 2001. A brief history of the formation of DNA databases in forensic science within Europe. Forensic Sci. Int. 119:225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullough, M. J., B. C. Ross, B. D. Dwyer, and P. C. Reade. 1994. Genotype and phenotype of oral Candida albicans from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Microbiology 140:1195-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullough, M. J., B. C. Ross, and P. C. Reade. 1995. Genetic differentiation of Candida albicans strains by mixed-linker polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Med. Vet. Mycol. 33:77-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzgar, D., A. van Belkum, D. Field, R. Haubrich, and C. Wills. 1998. Random amplification of polymorphic DNA and microsatellite genotyping of pre- and posttreatment isolates of Candida sp. from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients on different fluconazole regimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2308-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzgar, D., J. Bytof, and C. Wills. 2000. Selection against frameshift mutations limits expansion in coding DNA. Genome Res. 10:72-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaller, M. A., S. R. Lockhart, C. Pujol, J. A. Swails-Wenger, S. A. Messer, M. B. Edmond, R. N. Jones, R. P. Wenzel, and D. R. Soll. 1998. Hospital specificity, region specificity and fluconazole resistance of Candida albicans bloodstream isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1518-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto de Andrade, M., G. Schonian, A. Forche, L. Rosado, I. Costa, M. Muller, W. Presber, T. G. Mitchell, and H. J. Tietz. 2000. Assessment of genetic relatedness of vaginal isolates of Candida albicans from different geographical origins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pujol, C., S. Joly, B. Nolan, T Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1999. Microevolutionary changes in Candida albicans identified by the complex Ca3 fingerprinting probe involve insertions and deletions of the full-length repetitive sequence RPS at specific genomic sites. Microbiology 145:2635-2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roewer, L., M. Krawczak, S. Willuweit, M. Nagy, C. Alves, A. Amorim, K. Anslinger, C. Augustin, A. Betz, E. Bosch, A. Cagliá, A. Carracedo, D. Corach, T. Dobosz, B. M. Dupuy, S. Füredi, C. Gehrig, L. Gusmão, J. Henke, L. Henke, M. Hidding, C. Hohoff, B. Hoste, M. A. Jobling, H. J. Kärgel, P. de Knijff, R. Lessig, E. Liebeherr, M. Lorente, B. Martínez-Jarreta, P. Nievas, M. Nowak, W. Parson, V., L. Pascali, G. Penacino, R. Ploski, B. Rolf, A. Sala, U. Schmidt, C. Schmitt, P. M. Schneider, R. Szibor, J. Teifel-Greding, and M. Kayser. 2001. Online reference database of European Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat (STR) haplotypes. Forensic Sci. Int. 118:106-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohatiner, J. J. 1966. Relationship of Candida albicans in the genital and anorectal tracts. Br. J. Vener. 42:197-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmid, J., S. Herd, P. R. Hunter, R. D. Cannon, M. S. Yasin, S. Samad, M. Carr, D. Parr, W. McKinney, M. Schousboe, B. Harris, R. Ikram, M. Harris, A. Restrepo, G. Hoyos, and K. P. Singh. 1999. Evidence for a general purpose genotype in Candida albicans, highly prevalent in multiple geographic regions, patient types and types of infection. Microbiology 145:2405-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroppel, K., M. Rotman, R. Galask, K. Mac, and D. R. Soll. 1994. Evolution and replacement of Candida albicans strains during recurrent vaginitis demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2646-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shemer, R., Z. Weissman, N. Hashman, and D. Kornitzer. 2001. A highly polymorphic degenerate microsatellite for molecular strain typing of Candida krusei. Microbiology 147:2021-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherer, S., and D. A. Stevens. 1987. Applications of DNA typing methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:675-679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan, D. J., T. J. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennett, and D. C. Coleman. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterisation of a novel species associated with oral candidiasis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141:1507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thanos. M., G. Schonian, W. Meyer, C. Schweynoch, Y. Graser, T. G. Mitchell, W. Presber, and H. J. Tietz. 1996. Rapid identification of Candida species by DNA fingerprinting with PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:615-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tóth, G., Z. Gáspári, and J. Jurka. 2000. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 10:967-981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]