Abstract

The yeast high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) signaling pathway can be activated by either of the two upstream pathways, termed the SHO1 and SLN1 branches. When stimulated by high osmolarity, the SHO1 branch activates an MAP kinase module composed of the Ste11 MAPKKK, the Pbs2 MAPKK, and the Hog1 MAPK. To investigate how osmostress activates this MAPK module, we isolated both gain-of-function and loss-of-function alleles in four key genes involved in the SHO1 branch, namely SHO1, CDC42, STE50, and STE11. These mutants were characterized using an HOG-dependent reporter gene, 8xCRE-lacZ. We found that Cdc42, in addition to binding and activating the PAK-like kinases Ste20 and Cla4, binds to the Ste11–Ste50 complex to bring activated Ste20/Cla4 to their substrate Ste11. Activated Ste11 and its HOG pathway-specific substrate, Pbs2, are brought together by Sho1; the Ste11–Ste50 complex binds to the cytoplasmic domain of Sho1, to which Pbs2 also binds. Thus, Cdc42, Ste50, and Sho1 act as adaptor proteins that control the flow of the osmostress signal from Ste20/Cla4 to Ste11, then to Pbs2.

Keywords: HOG pathway, MAP kinase, signal transduction, yeast

Introduction

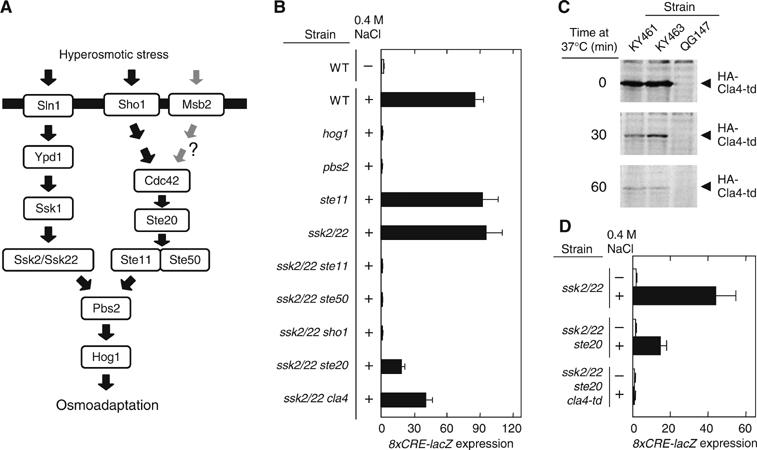

When exposed to hyperosmotic extracellular environments, the budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) activates the high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) signaling pathway, which culminates in phosphorylation, activation, and nuclear translocation of the Hog1 MAP kinase (MAPK). Activated Hog1 initiates an adaptive program that includes adjustments in cell cycle progression, regulation of protein translation, induction or repression of various genes, and synthesis and intracellular retention of the compatible osmolyte glycerol (Gustin et al, 1998; Hohmann, 2002). The current view of the HOG pathway is summarized in Figure 1A. Yeast has two putative osmosensors, Sln1 and Sho1, and perhaps a third one, Msb2, which are all structurally distinct and functionally independent of each other (Maeda et al, 1994, 1995; O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2002). Signals emanating from these sensors converge at a common MAPK kinase (MAPKK), Pbs2, which is the specific activator of Hog1 (Brewster et al, 1993; Maeda et al, 1994, 1995). The entire signal pathway from the cell surface sensors to the Hog1 MAPK will be referred to as the HOG pathway, while the branches upstream of Pbs2 are called the SLN1 and SHO1 branches, respectively.

Figure 1.

Ste20 and Cla4 are redundant in the HOG pathway. (A) Schematic model of the yeast HOG signal pathway. The horizontal bar represents the plasma membrane. The role of Msb2 in HOG pathway is unclear (O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2002; Cullen et al, 2004). (B) 8xCRE-lacZ expression accurately reflects the osmotic activation of the HOG pathway. Wild-type (TM141) and its derivatives with the indicated genotypes were transformed with the pRS414-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed before (−) or after (+) 30 min exposure to 0.4 M NaCl. Strains used are TM141, QG137, TM260, FP54, TM257, FP75, FP67, QG153, QG147, and QG148. (C) Degradation of Cla4-td at a nonpermissive temperature. KY461 (ssk2/22 ste20 cla4-td), KY463 (STE11-Q301P ssk2/22 ste20 cla4-td), and QG147 (ssk2/22 ste20) were grown exponentially at 25°C, transferred to 37°C, and at the indicated times, cell extracts were prepared. The HA-tagged Cla4-td protein was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. (D) Ste20 and Cla4 are redundant in the SHO1 branch. Exponentially growing cells of the indicated genotypes carrying the pRS414-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid were transferred from 25°C to 37°C 1 h before osmostress was applied. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed before (−) or after (+) 30 min exposure to 0.4 M NaCl. Strains used are TM257, QG147, and KY461.

The Sho1 osmosensor contains four transmembrane segments and a cytoplasmic SH3 domain that binds a proline-rich motif in the N-terminal region of Pbs2 (see Figure 5A). Sho1 is predominantly localized to the cytoplasmic membrane at regions of polarized growth, such as the emerging bud and the bud neck (Raitt et al, 2000; Reiser et al, 2000, 2003). Sho1 is absolutely required for activation of Hog1 via the SHO1 branch. In addition, Cdc42, Ste20, Ste50, and Ste11 have also been implicated in the SHO1 pathway (Posas and Saito, 1997; O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 1998; Posas et al, 1998; Raitt et al, 2000; Reiser et al, 2000). Cdc42 is a Rho-type small G-protein, and binds and activates Ste20, a prototype of the PAK family protein kinases (Lamson et al, 2002; Ash et al, 2003). Activated Ste20 phosphorylates the MAPKK kinase (MAPKKK) Ste11 on Ser-281, Ser-285, and Thr-286, and thus dissociates the Ste11 N-terminal inhibitory domain from its C-terminal catalytic domain (van Drogen et al, 2000). Ste50, an SAM (Sterile Alpha Motif) domain-containing protein, binds Ste11, itself another SAM domain-containing protein, via a heterotypic SAM–SAM interaction (Posas et al, 1998; Ramezani Rad et al, 1998; Grimshaw et al, 2004).

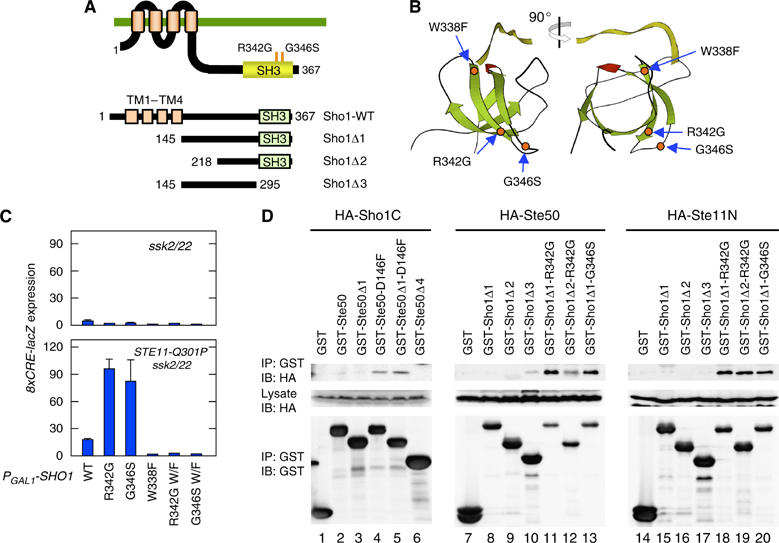

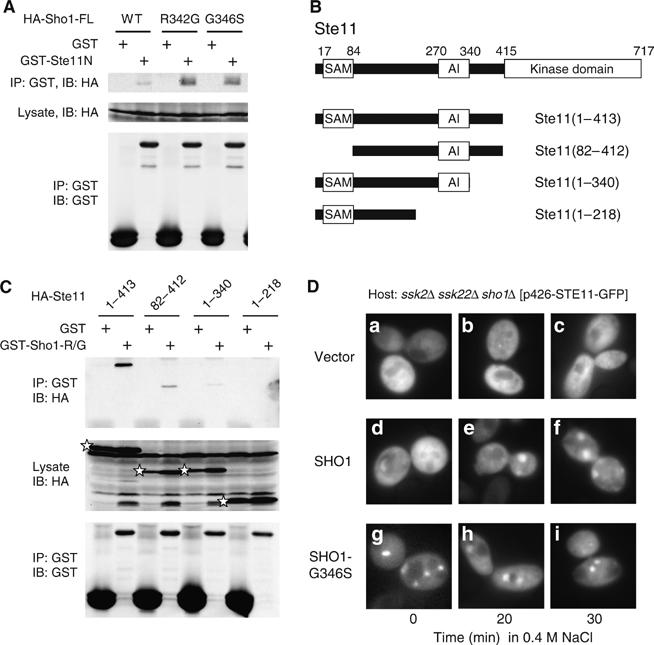

Figure 5.

Constitutively active Sho1 mutants. (A) Schematic diagrams of the Sho1 mutants used in this work. TM, transmembrane segment. (B) The predicted three-dimensional locations of the constitutively active Sho1 mutations R342G and G346S in the SH3 domain. The location of W338F that abrogates Pbs2 binding is also shown. The crystallographic structure of the human Fyn SH3 domain (green) complexed with a ten-residue proline-rich peptide (yellow) was used as a homologous model (PDB ID=1FYN). (C) Constitutively active Sho1 mutants induce 8xCRE-lacZ reporter expression in the presence of Ste11-Q301P. TM257 (ssk2 ssk22) and KT018 (STE11-Q301P ssk2 ssk22) carrying the pRS414-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid were transformed with pRS416-GAL1-SHO1 or one of its derivatives containing the indicated mutations. The Sho1 proteins were induced by 2% galactose for 2 h before cell extracts were prepared for β-galactosidase assay. W/F, W338F. (D) Binding of Sho1 to Ste50 and Ste11. KT045 (sho1 ste11 ste50 pbs2) was co-transformed with a YCpIF16-based plasmid (GAL1 promoter) for expression of HA-tagged protein and a pTEG1-based plasmid (TEF promoter) for expression of GST-fusion protein. HA-Sho1C includes residues 145–367, HA-Ste50 contains the entire Ste50 coding region (1–346), and HA-Ste11N contains residues 1–413. Cells were grown in CARaf medium, and expression of the fusion proteins was induced for 4 h by 2% galactose. GST-fusion proteins were captured by glutathione-Sepharose beads, and co-precipitated HA-tagged protein was detected by immunoblotting.

Many of these proteins are also involved in other MAPK pathways in yeast. Sho1, Cdc42, Ste20, Ste50, and Ste11, have been implicated in the filamentous growth (FG) pathway, and at least Cdc42, Ste20, and Ste11 are also essential in the mating pheromone responsive MAPK pathway (Dohlman and Thorner, 2001). In spite of the involvement of these molecules in multiple pathways, there is no nonphysiological crosstalk activation between the pathways. Thus, pheromone stimulation activates only the Fus3/Kss1 MAPKs, and osmotic stimulation normally activates only the Hog1 MAPK (Posas and Saito, 1997).

Specific docking interactions appear to play a critical role in the prevention of crosstalk between different MAPK pathways. We have shown that mammalian MAPKKs have a conserved docking site termed DVD (domain for versatile docking) at or near their C-terminus. Without the DVD site, mammalian MAPKKs cannot be bound to and phosphorylated by their specific MAPKKKs (Takekawa et al, 2005). Similarly, the yeast Ssk2 and Ssk22 MAPKKKs bind Pbs2 by a direct and specific docking interaction (Tatebayashi et al, 2003). However, a direct docking interaction with a MAPKK might be unsuitable for Ste11, because Ste11 is activated by several different upstream signals, and interacts with at least two different downstream MAPKKs (Pbs2 and Ste7) depending on the context of stimulation. In this paper, we analyzed two key steps in the SHO1 branch, namely activation of Ste11 by its upstream kinases (Ste20/Cla4), and activation of a downstream kinase (Pbs2) by activated Ste11. We demonstrate how Ste11 interacts with its upstream and downstream kinases by the adaptor functions of Cdc42, Ste50, and Sho1.

Results

An improved reporter for HOG pathway activation

We developed a new reporter gene for the HOG pathway activation, termed 8xCRE-lacZ, which contains eight tandem repeats of the ENA1-derived CRE sequence (Supplementary Figure S1A). In wild-type cells, a 30 min treatment with 0.4 M NaCl induced the reporter gene expression 50- to 100-fold (Supplementary Figure S1B). Although 8xCRE-lacZ is a simple quadruplication of the previously published 2xCRE-lacZ reporter (Proft et al, 2001), 8xCRE-lacZ has a better stimulated-to-basal signal ratio. Since the CRE-containing promoters are regulated both positively and negatively by the Sko1 transcription factor (Proft et al, 2001; Rep et al, 2001), induction of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter by osmostress is also dependent on the activator function of Sko1 (Supplementary Figure S1C). When unstimulated, 8xCRE-lacZ is fully repressed even in the absence of Sko1, whereas the 2xCRE-lacZ reporter gene is derepressed (Supplementary Figure S1C).

Disruption of a gene that is common to both the SLN1 and SHO1 branches, for example, hog1Δ or pbs2Δ, completely abolished reporter expression (Figure 1B). Inactivation of genes specific to either the SHO1 branch (e.g., ste11Δ) or to the SLN1 branch (e.g., ssk2Δ ssk22Δ; henceforth abbreviated as ssk2/22) had no discernible effect. In contrast, combinations of gene disruptions that inactivate both branches (e.g., ssk2/22 ste11, ssk2/22 ste50, or ssk2/22 sho1) completely abolished reporter expression. Thus, 8xCRE-lacZ is a faithful reporter of the HOG pathway activation.

Ste20 and Cla4 can independently activate the Ste11 MAPKKK in the SHO1 branch

In the pheromone MAPK pathway, the Ste20 PAK-like kinase is the activator of the Ste11 MAPKKK (Leberer et al, 1992). Analysis of HOG pathway signaling using this new reporter indicated, however, that the ssk2/22 ste20 mutant could still show a significant response to an osmotic stimulus (Figure 1B), indicating that Ste20 is not solely responsible for the SHO1 branch. Yeast has another PAK-like kinase that is very similar to Ste20, namely Cla4. These kinases share a common essential function, because their simultaneous loss is lethal (Cvrckova et al, 1995). Disruption of the CLA4 gene had a moderate effect on the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter induction (Figure 1B). To test if Ste20 and Cla4 are redundant in the SHO1 pathway, the effect of the ste20 cla4 double mutation, which is lethal, was tested using the temperature-sensitive cla4-td mutant (Holly and Blumer, 1999). The Cla4-td protein is not only inactivated rapidly at nonpermissive temperatures, but it is also degraded (Figure 1C). 8xCRE-lacZ reporter expression is completely abolished in the ssk2/22 ste20 cla4-td mutant, thus providing evidence that Ste20 and Cla4 are functionally redundant in the SHO1 branch (Figure 1D).

Ste50 and Sho1 are required in the HOG pathway downstream of Ste11 activation

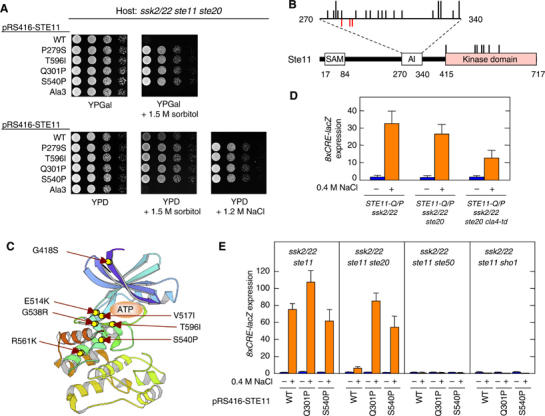

To study the activation mechanism of the SHO1 pathway, we isolated mutants that obviated the need for Ste20/Cla4 for 8xCRE-lacZ expression by osmostress. This was performed by screening for osmoresistant ‘revertants' of an ssk2/22 ste20 strain on YPGal+1.5 M sorbitol plates, where the endogenous CLA4 gene is insufficient to sustain cell growth (Raitt et al, 2000). Growth characteristics of some of the mutants are shown in Figure 2A. All the mutants thus isolated had a mutation in the STE11 gene; in all, 29 different STE11 alleles were found among 54 mutants analyzed (Supplementary Figure S2). Twenty-two alleles were clustered around the Ste20 phosphorylation sites (Figure 2B), and are likely to mimic the effect of phosphorylation by activated Ste20/Cla4 (van Drogen et al, 2000). These mutations collectively define the auto-inhibitory (AI) domain to be between amino acid residues 270 and 340. Seven additional alleles were in the C-terminal kinase catalytic domain; one of these (T596I) was identical to the previously known STE11-4 (Stevenson et al, 1992). The kinase domain mutations are clustered near the ATP-binding cleft (Figure 2C), and are thus likely to escape inhibition by the AI domain (van Drogen et al, 2000).

Figure 2.

Characterization of constitutively active Ste11 mutants. (A) Suppression of ste20Δ by constitutively active STE11 mutations. KY218 (ssk2 ssk22 ste11 ste20) carrying pRS416-STE11 or its derivatives was spotted on the indicated plates. Ala3 is a triple mutant of Ste20 phosphorylation sites, S281A S285A T286A. (B) Distribution of the constitutively active STE11 mutations. Below is the schematic diagram of Ste11 showing the SAM, autoinhibitory (AI) and kinase domains. AI domain is expanded above the diagram. Each black vertical bar represents a constitutively active STE11 mutation. Short bars indicate one allele at the position, while longer bars indicate two different alleles. Red bars below the horizontal line indicate phosphorylation sites. (C) The predicted three-dimensional locations of the constitutively active Ste11 mutations in the kinase domain. The crystallographic structure of the human PAK1 kinase domain was used as a model (PDB ID=1F3M). (D) Constitutively active Ste11 mutant bypasses both Ste20 and Cla4. Exponentially growing cells of the indicated genotypes carrying the pRS414-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid were transferred from 25°C to 37°C 1 h before osmostress was applied. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed before (−) or after (+) 30 min exposure to 0.4 M NaCl. Strains used are KT018, KT031, and KY463. (E) Constitutively active Ste11 mutants require Ste50 and Sho1 for 8xCRE-lacZ induction. Mutant strains of the indicated genotypes carrying a 8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid and pRS416-STE11 or its indicated derivative were grown exponentially and incubated for 30 min with (+) or without (−) 0.4 M NaCl, before preparation of cell extracts for β-galactosidase assay. Strains used are FP75, KY213, KY444, and KY452.

When a constitutively active STE11 allele was expressed from the native STE11 gene locus, the HOG pathway was activated by osmostress in the absence of both Ste20 and Cla4, as we expected (Figure 2D). However, 8xCRE-lacZ expression was induced only when hyperosmotic stress was applied. This result was unexpected, because we and others have shown previously that constitutively active Ste11 mutants (e.g., Ste11ΔN or Ste11-Asp3) could activate the Hog1 MAPK in the absence of stress (Posas and Saito, 1997; van Drogen et al, 2000). We found that the expression level of Ste11 mutant protein was responsible for these different results. Thus, if Ste11-Q301P was sufficiently overexpressed, it could induce the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter without any external osmostress (Supplementary Figure S3A), even in ste50Δ or sho1Δ cells (Supplementary Figure S3B). Correspondingly, overexpression of Ste11-Q301P rescued the osmosensitivity of both ssk2/22 ste11 ste50 and ssk2/22 ste11 sho1 mutants (Supplementary Figure S4A and B). These results give the misleading impression that neither Ste50 nor Sho1 is needed once Ste11 is activated. In contrast, when hyperactive STE11 mutant genes (STE11-Q301P and STE11-S540P) were expressed from the native STE11 promoter, induction of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter depended absolutely on the presence of both Ste50 and Sho1, and stress (Figure 2E). Consistently, none of the hyperactive Ste11 mutations could rescue the osmosensitive growth defect of ssk2/22 ste11 ste50 and ssk2/22 ste11 sho1 mutants (Supplementary Figure S4C, and data not shown). Thus, only by expression of the constitutively active Ste11 mutant proteins at physiologically relevant levels, a more subtle regulation of HOG pathway activation become discernible.

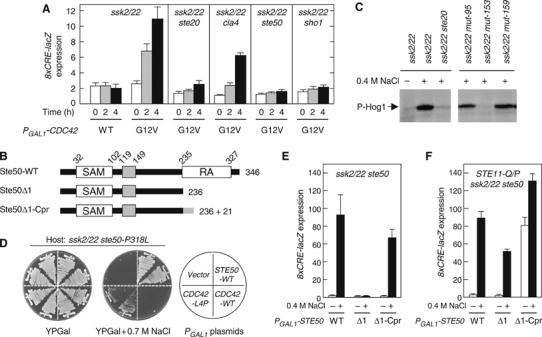

To further analyze the role of Ste50 and Sho1 in Ste11 function, we tested the necessity for Ste50 and Sho1 for expression of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter following activation of Ste11 by Ste20/Cla4. Activation of Ste20 and Cla4 by expression of the constitutively active Cdc42-G12V, which binds to their CRIB domains (Lamson et al, 2002), induced the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter (Figure 3A). This induction was inhibited significantly by ste20Δ and moderately by cla4Δ. More important, both Ste50 and Sho1 were needed for the 8xCRE reporter expression by constitutively activated Cdc42 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Interaction between Cdc42 and Ste50. (A) Induction of the HOG reporter by the constitutively active Cdc42-G12V. Strains of the indicated genotypes were transformed with an 8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid and pYES2 (a multicopy plasmid with the GAL1 promoter) encoding either the wild-type Cdc42 (WT) or Cdc42-G12V. Expression of the Cdc42 protein was induced for 0, 2, or 4 h by 2% galactose, before preparation of cell extracts for β-galactosidase assay. Strains used are TM257, QG147, QG148, FP67, and QG153. (B) Schematic diagram of Ste50. Boxes indicate the SAM and RA domains and a central conserved region. Deletion (Δ1) and membrane-targeting (Δ1-Cpr) mutants are also shown. Cpr, C-terminal prenylation signal of Ras2. (C) The mut-153 (ste50-P318L) strain is defective in Hog1 phosphorylation. Exponentially growing cells were stimulated with 0.4 M NaCl for 5 min before cell extracts were prepared. Phosphorylated Hog1 was probed by immunoblotting using anti-phospho p38 antibody. Control cells on the left panel are TM252 and FP53. mut-95 and mut-159 are irrelevant control mutants isolated in the same screening. (D) Suppression of the osmosensitivity of ste50-P318L mutant cells by CDC42-L4P. FP67 (ssk2 ssk22 ste50) carrying pRS416-ste50-P318L was transformed with YCpIF16 (a single-copy vector with the GAL1 promoter) encoding the indicated gene, and streaked on YPGal plates with or without 0.7 M NaCl. (E, F) A membrane-targeting signal functionally substitutes for the Ste50 RA domain. Host strains of the indicated genotypes (FP67 and KT049) carrying pRS416-8xCRE-lacZ were transformed with YCpIF16-STE50 or its mutant derivatives. Cells were grown exponentially in CARaf, induced for Ste50 expression for 1.5 h by adding galactose to 2%, and incubated for an additional 30 min with (+) or without (−) 0.4 M NaCl in the media.

These results demonstrate that both Ste50 and Sho1 are required even after Ste11 has been activated by Ste20/Cla4. We call such functions their post-Ste11 functions. Both Ste50 and Sho1, however, also have functions upstream of Ste11 activation, which we call their pre-Ste11 functions. In order to clearly understand how these molecules work in the HOG pathway, it is necessary to distinguish their two functional aspects. In the next section, we will define the pre-Ste11 function of Ste50. The pre-Ste11 function of Sho1, namely its osmosensor function, will be described elsewhere.

Interaction between Cdc42 and Ste50

Ste50 comprises three conserved domains (Ramezani-Rad, 2003): the N-terminal SAM domain (amino acids 32–102), which interacts constitutively with the SAM domain in Ste11; a central conserved domain of previously unknown function (amino acids 119–149); and the C-terminal Ras-association (RA) domain (amino acids 235–327) (Figure 3B). For the FG pathway, it was recently demonstrated that binding of Cdc42 to the Ste50 RA domain was essential for signaling (Truckses et al, 2006). Either the GTP or the GDP form of Cdc42 can bind the RA domain. As Cdc42 is membrane-anchored by prenylation (Johnson, 1999), binding of Cdc42 to the Ste50 RA domain will translocate the otherwise cytoplasmic Ste11–Ste50 complex to the plasma membrane, where the Cdc42-bound Ste20 is also localized. Co-localization of activated Ste20 and the Ste11–Ste50 complex activates Ste11.

We therefore examined whether the Cdc42–Ste50 interaction is also involved in the HOG pathway. In a genetic screening designed to isolate mutants defective in the SHO1 branch, we found a ste50 mutant in which Pro-318 in the RA domain was altered to Leu. The ssk2/22 ste50-P318L strain was defective in Hog1 phosphorylation when stimulated by osmotic stress (Figure 3C). Although it was less osmosensitive than the null ssk2/22 ste50Δ mutant, the ssk2/22 ste50-P318L mutant failed to grow on relatively stringent osmotic conditions, such as YPGal+0.7 M NaCl (Figure 3D). Overexpression of the wild-type CDC42 gene did not suppress the osmosensitive phenotype of ssk2/22 ste50-P318L. However, we could isolate CDC42 mutants that suppressed the osmosensitivity of ssk2/22 ste50-P318L. Fourteen independently isolated CDC42 mutants all had in common a Leu-4 to Pro (L4P) mutation, suggesting that Cdc42-L4P restores the lost Ste50–Cdc42 interaction caused by Ste50-P318L.

Interestingly, Leu-4 lies very close to Ile-46 on the predicted three-dimensional structure of Cdc42 based on the homologous human Cdc42Hs (Supplementary Figure S5). The Ile-46 to Met (I46M) substitution in Cdc42 inhibits the binding between Cdc42 and the Ste50 RA domain, and cdc42-I46M mutant cells are defective in the FG response (Mösch et al, 2001; Truckses et al, 2006). The positions of Leu-4 and Ile-46 are far from the GTP binding/hydrolysis domains and the effector binding regions called Switch I (residues 26–40) and Switch II (residues 58–76) (Johnson, 1999). It is therefore likely that Cdc42 binds to the Ste50 RA domain and to the Ste20/Cla4 CRIB domain via different regions of the molecule.

To test if a membrane-targeting signal could functionally substitute for the Ste50 RA–Cdc42 interaction, we made Ste50 RA deletion mutants without (Ste50Δ1) or with (Ste50Δ1-Cpr) the Ras2 C-terminal prenylation site (Bhattacharya et al, 1995) (see Figure 3B). Ste50Δ1-Cpr transduces the SHO1 branch signal efficiently when stimulated by 0.4 M NaCl (Figure 3E). In contrast, the Ste50Δ1 mutant is totally defective in this respect. However, in cells that express constitutively active Ste11 (such as Q301P), the Ste50Δ1 mutant can transduce the HOG signal, because co-localization of the Ste11–Ste50 complex with Ste20 (or Cla4) is unnecessary for Ste11 activation (Figure 3F). Thus, one role of Ste50 seems to be to localize the Ste11–Ste50 complex on the membrane by binding to the membrane-linked Cdc42. As Cdc42-bound Ste20 and Cla4 are also localized on the membrane, the upstream enzyme (Ste20 or Cla4) and downstream substrate (the Ste11–Ste50 complex) will be both concentrated on the membrane. Alternatively, a single molecule of Cdc42 might bind both Ste20 (or Cla4) and the Ste11–Ste50 complex, bringing them very close together.

Constitutively active Ste50 mutants

Expression of Ste50Δ1 in the STE11-Q301P mutant cells still requires osmostress stimulation to induce the reporter gene (Figure 3F), whereas expression of Ste50Δ1-Cpr in the same cells spontaneously induces 8xCRE-lacZ expression without osmostress, indicating that membrane-targeting of the Ste11–Ste50 complex mimics another essential event in the SHO1 branch that occurs after Ste11 has been activated. Since the Ste50Δ1 mutant protein lacks the RA domain, this second membrane-targeting event is independent of the RA domain. To identify the nature of this post-Ste11 event, we screened for STE50 mutants that had a phenotype similar to STE50Δ1-Cpr; that is, a capacity to spontaneously induce the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter when co-expressed with a constitutively active Ste11. Seven such STE50 mutants were isolated, all of which had a mutation at Asp-146 in the conserved central domain: five were D146V, one was D146A, and another was D146Y. The equivalent position of D146 in the Ste50 orthologs of other yeasts is often occupied by the conserved Glu residue (Ramezani-Rad, 2003). Co-expression of STE50-D146V and constitutively active STE11-Q301P induced the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter in the absence of any osmostress stimulus (Figure 4A). Site-directed mutagenesis of Ste50 Asp-146 to Cys, Leu, or Phe also created mutants of a similar phenotype, whereas mutations to Ser or Asn had little or no effect (Figure 4A and data not shown). We chose the strongest allele, STE50-D146F (STE50-D/F), for further characterization.

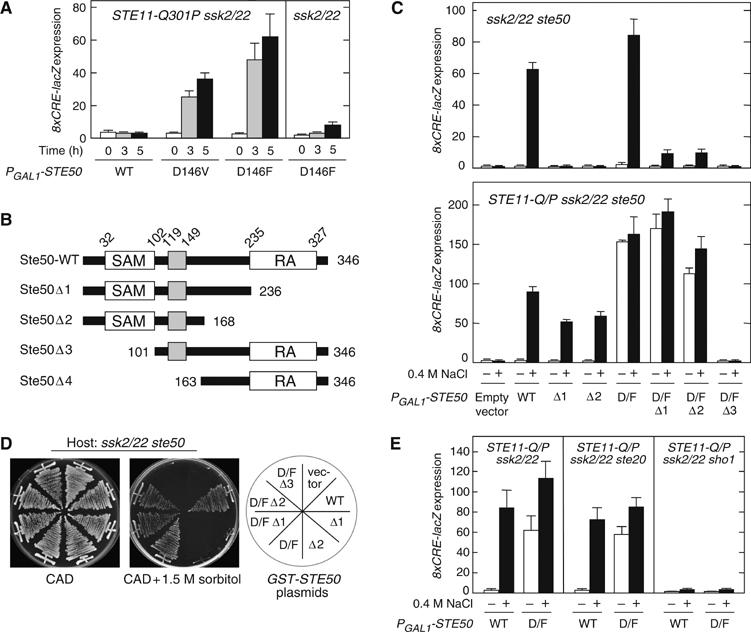

Figure 4.

Constitutively active Ste50 mutant. (A) Constitutively active Ste50 mutants. KT018 (STE11-Q301P ssk2 ssk22) and TM257 (ssk2 ssk22) carrying the pRS416-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid were transformed with YCpIF16-STE50 or its derivative as indicated. Ste50 expression was induced by 2% galactose for 0, 3, and 5 h before cell extracts were prepared for β-galactosidase assay. (B) Schematic diagrams of the Ste50 deletion constructs used in this work. (C) Induction of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter by the constitutively active Ste50-D146F mutant. FP67 (ssk2 ssk22 ste50) and KT049 (STE11-Q301P ssk2 ssk22 ste50) carrying the pRS416-8xCRE-lacZ reporter plasmid were transformed with YCpIF16-STE50 or one of its derivatives containing the indicated mutations. Cells were grown exponentially in CARaf, induced for Ste50 expression for 1.5 h by 2% galactose, and incubated for additional 30 min with (+) or without (−) 0.4 M NaCl in the media, before cell extracts were prepared for β-galactosidase assay. D/F, D146F. (D) Intragenic suppression of the Ste50 RA domain deletion mutants by D146F. FP67 (ssk2 ssk22 ste50) was transformed with YCpIF16 (a single-copy vector with the GAL1 promoter) encoding the indicated gene, and streaked on CAD plates with or without 1.5 M sorbitol. (E) Constitutively active Ste50-D146F requires Sho1 for 8xCRE-lacZ reporter expression. Cells of the indicated genotypes (KT018, KT031, and KT028) carrying pRS416-8xCRE-lacZ were transformed with either YCpIF16-Ste50 (WT) or YCpIF16-Ste50-D146F (D/F). Cell extracts for β-galactosidase assay were prepared as in (C).

Spontaneous induction of 8xCRE-lacZ by Ste50-D146F was dependent on the simultaneous presence of activated Ste11, because no induction of the reporter occurred in the STE11 wild-type cells (Figure 4A). To examine if induction of 8xCRE-lacZ expression by STE50-D146F plus STE11-Q301P requires the Ste50 RA or SAM domain, we used the Ste50 Δ1, Δ2, and Δ3 mutants shown in Figure 4B. The SAM-mediated Ste11–Ste50 association is essential, because Ste50-D146F Δ3 cannot induce the reporter in STE11-Q301P cells (Figure 4C, lower panel). In contrast, the RA domain is dispensable, as both Ste50-D146F Δ1 and Ste50-D146F Δ2 induced the reporter as strongly as the parental Ste50-D146F in STE11-Q301P cells. Even in the STE11 wild-type cells, the STE50-D146F mutation significantly improved the signaling efficiencies of RA domain deletion mutants (Δ1 and Δ2) under osmostress conditions (Figure 4C, upper panel). Consistent with these results, STE50-D146F Δ1 and STE50-D146F Δ2 mutant cells were osmoresistant, whereas the corresponding ste50 Δ1 and ste50 Δ2 mutants were osmosensitive (Figure 4D). The phenotypic similarity between STE50-D146F Δ1 and STE50 Δ1-Cpr suggests that the STE50-D146F mutation induces Ste50 membrane-localization, independently of the RA domain.

Consistent with the model that Ste20 is needed only to activate Ste11, expression of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter is induced by the combination of Ste11-Q301P and Ste50-D146F in the absence of Ste20 (Figure 4E, middle panel). In contrast, Sho1 is essential under the same conditions (Figure 4E, right panel), suggesting that Sho1 has a function downstream of Ste11 activation, possibly in the predicted membrane-targeting of the Ste11–Ste50 complex.

Constitutively active Sho1 mutants

To determine if Sho1 mediates membrane-targeting of Ste50, we screened for SHO1 mutants that have a similar phenotype to STE50-D146F, namely, induction of the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter when co-expressed with constitutively active Ste11-Q301P (see Materials and methods). Two SHO1 alleles, R342G and G346S, were thus isolated. Both mutations are in the SH3 domain (Figure 5A and B). The equivalent position of R342 in the Sho1 orthologs of other yeasts and fungi, such as Kluyveromyces and Aspergillus, is either arginine or lysin, while that of G346 seems even more conserved. Co-expression of Ste11-Q301P and either Sho1-R342G or Sho1-G346S induced 8xCRE-lacZ reporter expression (Figure 5C, lower panel). External osmostress did not further increase reporter expression, indicating that the SHO1 branch was maximally activated by the combination of a hyper-active Sho1 mutation and a hyper-active Ste11 mutation (Supplementary Figure S6A). In STE11 wild-type cells, however, neither Sho1-R342G nor Sho1-G346S could spontaneously induce 8xCRE-lacZ reporter expression (Figure 5C, upper panel). Both R342G and G346S, when located on the three-dimensional structure of the homologous Fyn SH3 domain (Noble et al, 1993), are diametrically opposite to the binding site for proline-rich peptides, suggesting that these mutations affect a function of Sho1 different from Pbs2 binding (Figure 5B). Because phenotypic manifestation of the SHO1-R342G and SHO1-G346S mutations depends on the presence of hyperactive Ste11, they likely affect a post-Ste11 event.

Neither Sho1-R342G nor Sho1-G346S could induce the 8xCRE-lacZ reporter in ste50Δ mutant cells, even in the presence of hyperactive Ste11-Q301P (Supplementary Figure S6B). Thus, there are interesting similarities between Ste50-D146F and Sho1-R342G/Sho1-G346S: (1) they induce the reporter only in the presence of a constitutively active Ste11; (2) they are mutually dependent—Ste50-D146F requires Sho1 for reporter induction, and Sho1-R342G/Sho1-G346S requires Ste50; and (3) they are not synergistic—co-expression of Ste50-D146F and Sho1-R342G/Sho1-G346S did not induce reporter expression (Supplementary Figure S6C). Furthermore, these phenotypes are similar to the phenotype induced by membrane-targeting of Ste50 by attachment of a prenylation site. Thus, we hypothesized that the three mutations, Ste50-D146F, Sho1-R342G, and Sho1-G346S lie in regions that coordinate to target the Ste11–Ste50 complex to the membrane, perhaps by binding the Ste11–Ste50 complex to Sho1.

Interaction between Ste50 and Sho1

To test the above hypothesis, we first examined whether Ste50-D146F binds Sho1. GST-tagged Ste50 constructs (see Figure 4B), with or without the D146F mutation, were individually co-expressed with an HA-tagged Sho1 cytoplasmic region (HA-Sho1C, residues 145–367). We used a sho1Δ ste11Δ ste50Δ pbs2Δ host strain to prevent any indirect tethering of the Ste50 and Sho1 fusion proteins by endogenous proteins. The GST-Ste50 fusion proteins were captured by glutathione-beads, and co-precipitated HA-Sho1C was detected by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 5D (left panel), either GST-Ste50-D146F or GST-Ste50Δ1-D146F co-precipitated HA-Sho1C (lanes 4 and 5), while the wild-type GST-Ste50 or GST-Ste50Δ1 did not (lanes 2 and 3). GST-Ste50Δ4, which lacks the SAM and the central conserved domains, also did not bind HA-Sho1C. This pattern, as well as the location of the activating D146F mutation, suggests that the central conserved domain is important for Ste50–Sho1 binding.

Next, to locate the Ste50 binding site in Sho1, we tested several GST-tagged Sho1 deletion constructs (Figure 5A). GST-Sho1 constructs, with or without an activating mutation (R342G or G346S), were individually co-expressed with HA-Ste50 (full-length), in a sho1Δ ste11Δ ste50Δ pbs2Δ host. The GST-Sho1 fusion proteins were captured by glutathione-beads, and co-precipitated HA-Ste50 was detected. GST-Sho1Δ3 bound Ste50 very weakly (Figure 5D, lane 10). More stable binding was observed when either the R342G or G346S mutation was included in the Sho1 SH3 domain (Figure 5D, lanes 11–13). Deletion of the Sho1 residues 145–218 weakened the Ste50 binding significantly (lane 12). Thus, the strongest interaction between Sho1 and Ste50 occurred when both the residues 145–218 and an activating mutation in the SH3 domain (R342G or G346S) are present in Sho1. A plausible interpretation of these results is that Sho1 has two separate Ste50 binding sites: a weak constitutive binding site between residues 145–218, and a stronger but inducible binding site within the SH3 domain.

Direct interaction between Ste11 and Sho1

Zarrinpar et al (2004) reported that Sho1 directly bound the Ste11 N-terminal domain. Their in vivo binding experiments, however, were performed in a host that expressed Ste50, which might have tethered Sho1 and Ste11 under certain conditions. Thus, we re-examined the possible Sho1–Ste11 interaction in a mutant cell (sho1Δ ste11Δ ste50Δ pbs2Δ) that lacked all the known Sho1 interacters. In this mutant host, none of the GST-Sho1 constructs without an activating mutation bound the HA-tagged Ste11 N-terminal domain (HA-Ste11N) (Figure 5D, lanes 15–17). In contrast, constructs with an activating mutation, namely GST-Sho1Δ1-R342G, GST-Sho1Δ2-R342G, and GST-Sho1Δ1-G346S, did strongly bind HA-Ste11N (Figure 5D, lanes 18–20). In fact, GST-Sho1Δ1-R342G bound stronger to HA-Ste11N than to HA-Ste50 when both were co-expressed in the same cell (Supplementary Figure S7). According to Zarrinpar et al (2004), the major Ste11 binding site in Sho1 is located within residues 172–211. We did not, however, find any interaction between Sho1Δ3, which includes the putative binding site, and HA-Ste11N (Figure 5D, lane 17). To test the possibility that there is a weak basal interaction between Sho1 and the Ste11–Ste50 complex, and also to see if the full-length membrane-bound Sho1 can bind Ste11–Ste50, we co-expressed GST-Ste11N and HA-tagged full-length Sho1 (HA-Sho1-FL) with or without an activating mutation (R342G or G346S), in a wild-type yeast host. The wild-type Sho1 weakly bound to Ste11N, whereas the two SH3 domain mutants (R342G and G346S) bound to Ste11N more strongly (Figure 6A). These results suggest that the hyperactive phenotype of SHO1-R342G and SHO1-G346S is due to the higher affinities of the Sho1 mutant proteins for both Ste50 and Ste11. It is likely that these Sho1 mutants mimic the osmostress-stimulated state of the wild-type Sho1 protein. We could not, however, demonstrate an osmostress-induced association of the full-length wild-type Sho1 protein to Ste11N (data not shown), possibly because such an interaction is too fragile for detection unless locked in by constitutively activating mutations.

Figure 6.

Interaction between Sho1 and Ste11. (A) Binding of the full-length Sho1 to Ste11. TM141 (wild-type) cells were co-transformed with a YCpIF16-based plasmid that encodes HA-tagged full-length Sho1 protein with the indicated mutation, and pTEG1-STE11N, which encodes GST-Ste11N. See the Figure 5D legend for other details. (B) Schematic diagram of the Ste11 deletion constructs used for the co-immunoprecipitation assays in (C). Boxes indicate the SAM, AI, and kinase catalytic domains. (C) Binding of Ste11 N-terminal fragments to Sho1C-R342G. KT045 (sho1 ste11 ste50 pbs2) was co-transformed with a YCpIF16-based plasmid (GAL1 promoter) for expression of HA-tagged Ste11 N-terminal fragments as indicated, and a pTEG1-based plasmid (TEF promoter) for expression of GST-Sho1C-R342G (R/G) or GST alone. Cells were grown in CARaf medium, and expression of the fusion proteins was induced for 4 h by 2% galactose. GST-fusion proteins were captured by glutathione-Sepharose beads, and co-precipitated HA-tagged protein was detected by immunoblotting. The positions of HA-Ste11 proteins in the total lysate are indicated by stars: other bands are background. (D) QG153 (ssk2 ssk22 sho1) carrying pRS426-Ste11-GFP (in which Ste11-GFP is expressed under the control of the STE11 promoter) was co-transformed with a pRS414-based plasmid encoding either Sho1-WT or Sho1-G346S under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Cells were grown in CARaf to log phase, galactose was added to a final concentration of 2%, grown for 3 h, and stimulated with 0.4 M NaCl for indicated time. Cells were kept at the room temperature (23°C) after the NaCl addition.

The two constitutively activating Sho1 mutations are located diagonally opposite from the Pro-rich peptide binding (i.e., Pbs2 binding) site on the surface of the Sho1 SH3 domain (Figure 5B). This raises the interesting possibility that Sho1 might be able to bind both Ste11–Ste50 and Pbs2 simultaneously. To test this, we did the experiment shown in Figure 5C (bottom). In this experiment, the host cells express the wild-type Sho1 protein, which should be able to bind to Pbs2, but not to Ste11, in the absence of osmostress. In contrast, the plasmid-encoded Sho1-R342G W338F or Sho1-G346S W338F double mutant protein should constitutively bind to the Ste11–Ste50 complex, but not to Pbs2 because of the W338F mutation in the Pro-rich peptide binding site. Thus, there should be two populations of the Sho1 molecules in these cells: one bound only to Pbs2, and another bound only to the Ste11–Ste50 complex. The co-existence of the two separate complexes, however, was not sufficient to activate the HOG pathway, even in the presence of the hyperactive Ste11-Q301P (Figure 5C, bottom, rightmost two lanes). Thus, both the Ste11–Ste50 complex and Pbs2 might bind simultaneously to one Sho1 molecule to form a Ste11–Ste50–Sho1–Pbs2 complex, in order for Ste11 to activate Pbs2.

Finally, we mapped the Sho1 binding site in Ste11 using a series of deletion constructs (Figure 6B). HA-Ste11(82–413), which lacks the SAM domain, could still bind to GST-Sho1C-R342G, whereas HA-Ste11(1–340) and HA-Ste11(1–218) could not appreciably bind to GST-Sho1-R342G (Figure 6C). Furthermore, neither HA-Ste11(82–269) nor HA-Ste11(1–119) could bind to GST-Sho1-R342G (data not shown). Thus, we can tentatively conclude that the catalytic domain-proximal region of Ste11N (residues 340–413) is important for the direct Ste11–Sho1 interaction, although contributions from other regions cannot be excluded. The overall affinity between Sho1 and Ste11 in intact cells might also be bolstered by the interaction of Sho1 to Ste50, which is constitutively bound to Ste11.

Altered subcellular localization of Ste11 in Sho1 mutant cells

Ste11 and Ste50 are diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm in unstressed cells, but both proteins rearrange to a punctate pattern when cells are exposed to osmotic stress (Posas et al, 1998). To test if this re-localization is a consequence of Ste11 activation by the SHO1 branch, we examined the subcellular distribution of Ste11-GFP in sho1Δ mutant cells as well as in cells that express a hyperactive Sho1 mutant protein (Figure 6D). In cells that express the wild-type Sho1, localization of Ste11-GFP changes from the uniform cytoplasmic distribution to a punctate pattern upon osmostress stimulation (panels d–f). In contrast, in sho1Δ cells, no re-distribution of Ste11-GFP occurred (panels a–c). More important, in cells that express the hyperactive Sho1-G346S protein, Ste11-GFP formed the punctuate pattern without osmotic stress (panels g–i). Sho1-R342G had the same effect (data not shown). Thus, the observed Ste11 re-localization is a consequence of the Ste11 activation, induced either by osmotic stress or by a hyperactive Sho1 mutation. In either case, however, membrane localization of Ste11-GFP was not so apparent. This might imply either that recruitment of the Ste11–Ste50 complex to the membrane by Cdc42 and Sho1 is a short-lived process, or that a relative small subpopulation of the Ste11–Ste50 complex is recruited to the membrane. A new approach will be needed to address this problem.

Discussion

In this paper, we described the two crucial activation steps in the SHO1 branch of the HOG pathway: the first step being activation of Ste11 by the PAK-like kinases Ste20/Cla4, and the second step that of Pbs2 by activated Ste11.

Initially, we developed an improved reporter for the HOG pathway activation, 8xCRE-lacZ. It has a better stimulated-to-basal signal ratio than the previously reported 2xCRE-lacZ reporter (Proft et al, 2001), apparently because 8xCRE-lacZ is repressed even in the absence of the Sko1 repressor-activator. The mechanism of Sko1-independent repression of 8xCRE-lacZ is unknown at the moment. Although useful, 8xCRE-lacZ has also limitations common to many gene expression-based reporters. For example, its response is delayed compared to phosphorylation of the Hog1 MAPK. Also, because β-galactosidase is a stable enzyme, it is not suitable for studying adaptive mechanisms. Nonetheless, the use of this reporter was instrumental to many findings described in this paper.

We can summarize the activation mechanism of the SHO1 pathway, based on the previous knowledge and the current data, as follows (Figure 7A; steps correspond to the numbers in parentheses in the figure). Initially, by an as yet unknown mechanism, osmostress converts Cdc42 to its active, GTP-bound, form. Cdc42-GTP then binds to either Ste20 or Cla4 and activates these kinases (steps 1–2). Our result showing that Ste20 and Cla4 are redundant in the HOG pathway explains why ssk2/22 ste20 mutants are less osmosensitive than ssk2/22 ste11 mutants (Posas and Saito, 1997; Raitt et al, 2000). More important, it indicates that there is a difference in the mechanisms of Ste11 activation between the pheromone MAPK pathway, which is totally dependent on Ste20, and the HOG MAPK pathway that can use either Ste20 or Cla4. In the mating pathway, Cla4 is not activated by the mating factors, perhaps because it does not have a Gβ/γ-binding site (Leeuw et al, 1998). In contrast, in the HOG pathway, both Ste20 and Cla4 seem to be activated by Cdc42.

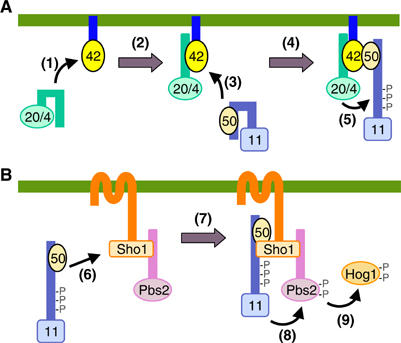

Figure 7.

Schematic model of the sequential docking interactions in the SHO1 pathway. (A) Activation of Ste11 by Ste20 is mediated by indirect docking via Ste50 and Cdc42. (B) Activation of Pbs2 by Ste11 is mediated by indirect docking via Ste50 and Sho1. The green horizontal bars represent the plasma membrane. 11, Ste11; 20/4, Ste20/Cla4; 42, Cdc42; 50, Ste50. The parenthesized numbers in the figure correspond to the step numbers in the text.

At the same time as the above steps, or perhaps somewhat later, Cdc42-GTP binds to the RA domain in Ste50 (step 3). As Ste50 is constitutively bound to Ste11, these interactions will localize the activated enzyme (Ste20 or Cla4) and their specific substrate (Ste11) in the same area of the plasma membrane. We might even speculate that one molecule of Cdc42 binds both Ste20 (or Cla4) and the Ste11–Ste50 complex (step 4). In either case, Ste20/Cla4 phosphorylates the residues in the auto-inhibitory domain of Ste11, leading to its activation (step 5). A relatively weak affinity between Cdc42 and Ste50 might ensure that the activated Ste11–Ste50 complex can detach from Cdc42, and participate in the following steps (Figure 7B). Thus, in the next step, stimulated Sho1 binds the activated Ste11–Ste50 complex (step 6). As Sho1 also binds to Pbs2, these interactions bring the activating enzyme (Ste11) and its specific substrate (Pbs2) together (step 7). Ste11 phosphorylates residues in the activation loop of Pbs2, leading to its activation (step 8). Activated Pbs2 then phosphorylates and activates the Hog1 MAPK (step 9).

Thus, unlike other MAPKKKs studied so far, Ste11 uses an indirect docking mechanism to bind its specific substrate Pbs2. In the mating pathway, Ste11 interacts with its substrate MAPKK Ste7 by docking to the Ste5 scaffold protein. By the adaptor proteins (Sho1 and Ste5) that interact with both Ste11 and one of its substrate MAPKKs (Pbs2 and Ste7), Ste11 can thus change its MAPKK partners depending on the incoming stimulus.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains

All yeast mutants used in this work are derivatives of the S288C strain (Table I).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this work

| Strain | Genotype | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| FP53 | MATa ura3 leu2 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷HIS3 | F Posas |

| FP54 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ste11∷HIS3 | Posas et al (1998) |

| FP58 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ste20∷HIS3 | Raitt et al (2000) |

| FP66 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ste50∷HIS3 | Posas et al (1998) |

| FP67 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste50∷HIS3 | Raitt et al (2000) |

| FP75 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷HIS3 | Posas et al (1998) |

| KT007 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 pbs2∷HIS3 FUS1-lacZ∷LEU2 | Tatebayashi et al (2003) |

| KT018 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 | K Tatebayashi |

| KT028 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 sho1∷HIS3 | K Tatebayashi |

| KT029 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste50∷hisG | K Tatebayashi |

| KT031 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷HIS3 | K Tatebayashi |

| KT045 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 sho1∷HIS3 ste11∷KanMX6 ste50∷hisG pbs2∷LEU2 | K Tatebayashi |

| KT049 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste50 ∷HIS3 | K Tatebayashi |

| KT051 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 sho1∷hphMX4 ste11∷KanMX6 ste50∷hisG pbs2∷LEU2 | K Yamamoto |

| KT500 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 pbs2∷HIS3 | Tatebayashi et al (2003) |

| KY163 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷KanMX6 | K Yamamoto |

| KY213 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷hisG ste20∷KanMX6 | K Yamamoto |

| KY218 | MATa ura3 leu2 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷hisG ste20∷KanMX6 | K Yamamoto |

| KY444 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷KanMX6 ste50∷HIS3 | K Yamamoto |

| KY452 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷HIS3 sho1∷KanMX6 | K Yamamoto |

| KY457 | MATa ura3 lue2 trp1∷hisG his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷hisG ste20∷KanMX6 lys2∷8xCRE-CYC-HIS3 | K Yamamoto |

| KY461 | MATα leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷KanMX6 cla4∷HIS3 URA3∷cla4-75-td | K Yamamoto |

| KY463 | MATα leu2 trp1 his3 STE11-Q301P ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷KanMX6 cla4∷HIS3 URA3∷cla4-75-td | K Yamamoto |

| MA001 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste11∷HIS3 | T Maruoka |

| QG137 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 hog1∷LEU2 | Q Ge |

| QG147 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 ste20∷HIS3 | Q Ge |

| QG148 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 cla4∷HIS3 | Q Ge |

| QG153 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 sho1∷HIS3 | Q Ge |

| TA014 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 sko1∷KanMX6 | K Tanaka |

| TM141 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 | Posas et al (1996) |

| TM252 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 | Maeda et al (1995) |

| TM257 | MATα ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 | T Maeda |

| TM258 | MATa ura3 leu2 ssk2∷LEU2 ssk22∷LEU2 | T Maeda |

| TM260 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 pbs2∷LEU2 | Maeda et al (1995) |

| TM286 | MATa ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 sho1∷HIS3 | T Maeda |

Media and buffers

CAD medium consists of 0.67% yeast nitrogen base (Sigma), 2% glucose, 0.5% casamino acid (Sigma) and appropriate supplements. SRaf medium consists of 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% raffinose with appropriate yeast synthetic dropout medium supplement. Other yeast media, buffers, and standard genetic procedures were as described previously (Rose and Broach, 1991; Tatebayashi et al, 2003).

Plasmids

Deletion and missense mutants were constructed by a PCR-based strategy and/or by oligonucleotide-based mutagenesis. All mutations were confirmed by nucleotide sequence determination.

Reporter assay

At least three independent transformants were freshly grown, and induced for reporter expression as described in each figure legend. β-Galactosidase activities were assayed as we described previously (Tatebayashi et al, 2003).

Isolation of Ste11, Sho1, Ste50, and Cdc42 mutants

Details of mutant isolation is available in the Supplementary data available at The EMBO Journal Online.

In vivo co-precipitation assay

In vivo co-precipitation assays were conducted essentially as described previously (Posas et al, 1996). In typical experiments, a 500 μg aliquot of protein was incubated with 50 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads for 3 h at 4°C before washing. Proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane, probed with the B14 anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody (Roche), and developed by the ECL reagent (Amersham Biosciences). Digital images were captured using Fuji LAS-1000.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence images were captured using a Nikon TE-2000 inverted microscope equipped with a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ CCD camera, the Nikon B-2E/C filter set, and the Universal Imaging Metamorph software.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgments

We thank T Maeda, Q Ge and F Posas (former members of the Saito laboratory) for previously unpublished yeast strains, K Tanaka (Hokkaido University) for a plasmid, Y Tsukamoto (Iwate College of Nursing) for a genomic DNA library, J Thorner (UC Berkeley) for sending a manuscript before publication, P O'Grady for editing the manuscript, and M Imai for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and a grant from the Salt Science Research Foundation (No. 0420).

References

- Ash J, Wu C, Larocque R, Jamal M, Stevens W, Osborne M, Thomas DY, Whiteway M (2003) Genetic analysis of the interface between Cdc42p and the CRIB domain of Ste20p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 163: 9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Chen L, Broach JR, Powers S (1995) Ras membrane targeting is essential for glucose signaling but not for viability in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 2984–2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster JL, de Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC (1993) An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science 259: 1760–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen PJ, Sabbagh W Jr, Graham E, Irick MM, van Olden EK, Neal C, Delrow J, Bardwell L, Sprague GF Jr (2004) A signaling mucin at the head of the Cdc42- and MAPK-dependent filamentous growth pathway in yeast. Genes Dev 18: 1695–1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvrckova F, De Virgilio C, Manser E, Pringle JR, Nasmyth K (1995) Ste20-like protein kinases are required for normal localization of cell growth and for cytokinesis in budding yeast. Genes Dev 9: 1817–1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman HG, Thorner JW (2001) Regulation of G protein-initiated signal transduction in yeast: paradigms and principles. Annu Rev Biochem 70: 703–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw SJ, Mott HR, Stott KM, Nielsen PR, Evetts KA, Hopkins LJ, Nietlispach D, Owen D (2004) Structure of the sterile α motif (SAM) domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-modulating protein Ste50 and analysis of its interaction with the Ste11 SAM. J Biol Chem 279: 2192–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin MC, Albertyn J, Alexander M, Davenport K (1998) MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 1264–1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann S (2002) Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66: 300–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly SP, Blumer KJ (1999) PAK-family kinases regulate cell and actin polarization throughout the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 147: 845–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DI (1999) Cdc42: an essential Rho-type GTPase controlling eukaryotic cell polarity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63: 54–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamson RE, Winters MJ, Pryciak PM (2002) Cdc42 regulation of kinase activity and signaling by the yeast p21-activated kinase Ste20. Mol Cell Biol 22: 2939–2951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leberer E, Dignard D, Harcus D, Thomas DY, Whiteway M (1992) The protein kinase homologue Ste20p is required to link the yeast pheromone response G-protein βγ subunits to downstream signalling components. EMBO J 11: 4815–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuw T, Wu C, Schrag JD, Whiteway M, Thomas DY, Leberer E (1998) Interaction of a G-protein β-subunit with a conserved sequence in Ste20/PAK family protein kinases. Nature 391: 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Takekawa M, Saito H (1995) Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science 269: 554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Saito H (1994) A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature 369: 242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mösch H-U, Köhler T, Braus GH (2001) Different domains of the essential GTPase Cdc42p required for growth and development of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 21: 235–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble MEM, Musacchio A, Saraste M, Courtneidge SA, Wierenga RK (1993) Crystal structure of the SH3 domain in human Fyn; comparison of the three-dimensional structures of SH3 domains in tyrosine kinases and spectrin. EMBO J 12: 2617–2624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke SM, Herskowitz I (1998) The Hog1 MAPK prevents cross talk between the HOG and pheromone response MAPK pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 12: 2874–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke SM, Herskowitz I (2002) A third osmosensing branch in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires the Msb2 protein and functions in parallel with the Sho1 branch. Mol Cell Biol 22: 4739–4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Saito H (1997) Osmotic activation of the HOG MAPK pathway via Ste11p MAPKKK: scaffold role of Pbs2p MAPKK. Science 276: 1702–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Witten EA, Saito H (1998) Requirement of STE50 for osmostress-induced activation of the STE11 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase in the high-osmolarity glycerol response pathway. Mol Cell Biol 18: 5788–5796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Maeda T, Witten EA, Thai TC, Saito H (1996) Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1-YPD1-SSK1 ‘two-component' osmosensor. Cell 86: 865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft M, Pascual-Ahuir A, de Nadal E, Arino J, Serrano R, Posas F (2001) Regulation of the Sko1 transcriptional repressor by the Hog1 MAP kinase in response to osmotic stress. EMBO J 20: 1123–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitt DC, Posas F, Saito H (2000) Yeast Cdc42 GTPase and Ste20 PAK-like kinase regulate Sho1-dependent activation of the Hog1 MAPK pathway. EMBO J 19: 4623–4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani Rad M, Jansen G, Bühring F, Hollenberg CP (1998) Ste50p is involved in regulating filamentous growth in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and associates with Ste11p. Mol Gen Genet 259: 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani-Rad M (2003) The role of adaptor protein Ste50-dependent regulation of the MAPKKK Ste11 in multiple signalling pathways of yeast. Curr Genet 43: 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser V, Raitt DC, Saito H (2003) Yeast osmosensor Sln1 and plant cytokinin receptor Cre1 respond to changes in turgor pressure. J Cell Biol 161: 1035–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser V, Salah SM, Ammerer G (2000) Polarized localization of yeast Pbs2 depends on osmostress, the membrane protein Sho1 and Cdc42. Nat Cell Biol 2: 620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rep M, Proft M, Remize F, Tamas M, Serrano R, Thevelein JM, Hohmann S (2001) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sko1p transcription factor mediates HOG pathway-dependent osmotic regulation of a set of genes encoding enzymes implicated in protection from oxidative damage. Mol Microbiol 40: 1067–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Broach JR (1991) Cloning genes by complementation in yeast. Methods Enzymol 194: 195–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson BJ, Rhodes N, Errede B, Sprague GF Jr (1992) Constitutive mutants of the protein kinase STE11 activate the yeast pheromone response pathway in the absence of the G protein. Genes Dev 6: 1293–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M, Tatebayashi K, Saito H (2005) Conserved docking site is essential for activation of mammalian MAP kinase kinases by specific MAP kinase kinase kinases. Mol Cell 18: 295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Takekawa M, Saito H (2003) A docking site determining specificity of Pbs2 MAPKK for Ssk2/Ssk22 MAPKKKs in the yeast HOG pathway. EMBO J 22: 3624–3634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truckses DM, Bloomekatz JE, Thorner J (2006) The RA domain of Ste50 adaptor protein is required for delivery of Ste11 to the plasma membrane in the filamentous growth signaling pathway of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 26: 912–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Drogen F, O'Rourke SM, Stucke VM, Jaquenoud M, Neiman AM, Peter M (2000) Phosphorylation of the MEKK Ste11p by the PAK-like kinase Ste20p is required for MAP kinase signaling in vivo. Curr Biol 10: 630–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinpar A, Bhattacharyya RP, Nittler MP, Lim WA (2004) Sho1 and Pbs2 act as coscaffolds linking components in the yeast high osmolarity MAP kinase pathway. Mol Cell 14: 825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures