Abstract

Coat protein (COP)–coated vesicles have been shown to mediate protein transport through early steps of the secretory pathway in yeast and mammalian cells. Here, we attempt to elucidate their role in vesicular trafficking of plant cells, using a combined biochemical and ultrastructural approach. Immunogold labeling of cryosections revealed that COPI proteins are localized to microvesicles surrounding or budding from the Golgi apparatus. COPI-coated buds primarily reside on the cis-face of the Golgi stack. In addition, COPI and Arf1p show predominant labeling of the cis-Golgi stack, gradually diminishing toward the trans-Golgi stack. In vitro COPI-coated vesicle induction experiments demonstrated that Arf1p as well as coatomer could be recruited from cauliflower cytosol onto mixed endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi membranes. Binding of Arf1p and coatomer is inhibited by brefeldin A, underlining the specificity of the recruitment mechanism. In vitro vesicle budding was confirmed by identification of COPI-coated vesicles through immunogold negative staining in a fraction purified from isopycnic sucrose gradient centrifugation. Similar in vitro induction experiments with tobacco ER/Golgi membranes prepared from transgenic plants overproducing barley α-amylase–HDEL yielded a COPI-coated vesicle fraction that contained α-amylase as well as calreticulin.

INTRODUCTION

Protein trafficking in the secretory and endocytotic pathways is facilitated by coated vesicles (Rothman and Wieland, 1996; Robinson et al., 1998). Research on mammalian and yeast cells has established that two different types of non-clathrin-coated vesicles are responsible for transport events occurring between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi apparatus and for intra-Golgi transport. Whereas investigators generally agree that COPII–coated vesicles bud from the ER and transport proteins in the anterograde direction (Barlowe et al., 1994; Bannykh and Balch, 1998), the function of COPI-coated vesicles remains controversial. Strong evidence suggests that COPI-coated vesicles are responsible for the recycling of escaped ER-resident proteins from post-ER compartments (Letourneur et al., 1994), but data have also been presented supporting a role in anterograde transport of proteins, especially within the Golgi stack (Orci et al., 1997; Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1998).

The formation of both types of COP-coated vesicles involves the recruitment of a coat protein complex (coatomer for COPI-coated vesicles, Sec23/24 and Sec13/31 dimers for COPII-coated vesicles) by a membrane-associated GTP binding protein (Arf1p and Sar1p for COPI and COPII, respectively; Schekman and Orci, 1996). Both Arf1p and Sar1p exist in the cytosol as GDP-bound forms and become converted to the GTP form through the action of a membrane-associated exchange factor, guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Helms and Rothman, 1992). For Sar1p, this is Sec12p, a transmembrane protein of the ER (Barlowe and Schekman, 1993); for Arf1p, the most likely candidates are Gea1/2p and ARNO (ARF nucleotide binding site opener; Chardin et al., 1996; Peyroche et al., 1996). Regarding COPI-coated vesicles, coatomer also interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of two types of transmembrane proteins: either a member of the p23/24 protein family (Bremser et al., 1999; Lavoie et al., 1999) or a dilysine motif present on type I membrane-spanning ER resident proteins (Cosson and Letourneur, 1994).

Coatomer has been isolated from mammalian (Waters et al., 1991) and yeast (Duden et al., 1994) cells and consists of seven polypeptides: α-COP (Ret1p), 135 kD; β-COP (Sec26p), 107 kD; β'-COP (Sec27p), 102 kD; γ-COP (Sec21p), 97 kD; δ-COP (Ret2p), 57 kD; ɛ-COP (Sec28p), 36 kD; and ζ-COP (Ret3p), 21 kD. γ-COP contains a binding site for both dilysine retrieval motifs and the diphenylalanine motif of p23 (Harter and Wieland, 1998). Structural homologies but not functional similarities exist between β-COP and the β-adaptins of clathrin-coated vesicles (Duden et al., 1991), between δ-COP and the μ-adaptins (Faulstich et al., 1996), and between ζ-COP and the σ-adaptins (Kuge et al., 1993).

Coatomer is assembled in the cytosol from its subunit polypeptides within 1 to 2 hr after their translation, is recruited onto membranes (Hara-Kuge et al., 1994), and is a stable structure for >50 hr (Lowe and Kreis, 1996), which suggests that the protein can be used in many cycles of vesicle formation. The initial binding of one coatomer to the cytoplasmic domain of p23 (in a tetrapeptide conformation) apparently induces the attachment of further coatomers and is considered the underlying mechanism for COPI-coated vesicle formation (Harter, 1999). As shown by immunogold electron microscopy, the membrane-bound coatomer in mammalian cells is localized mainly to the periphery of Golgi cisternae (Duden et al., 1991; Oprins et al., 1993; Orci et al., 1997) and occasionally to special domains of the ER (Orci et al., 1994). In addition, coatomer is prominent on membranes of the so-called ER–Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) (Oprins et al., 1993; Griffiths et al., 1995; Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999), a compartment for which plants have no direct structural counterpart.

Plant ARF1, Sar1, and Sec12 genes and proteins have been identified (d'Enfert et al., 1992; Regad et al., 1993; Bar-Peled and Raikhel, 1997). In addition, knowledge on the targeting and fusion machinery for transport vesicles in plants is rapidly expanding (reviewed in Robinson et al., 1998; Sanderfoot and Raikhel, 1999). Recently, we presented evidence for the existence of homologs of γ-COP (Sec21p) and Sec23p in cauliflower inflorescence and showed that these polypeptides are part of cytosolic complexes having the properties of coatomer and the Sec23/24 dimer (Movafeghi et al., 1999). Nevertheless, plant COPI- and COPII-coated vesicles have yet to be identified in situ and isolated. Isolation of such vesicles would facilitate the analysis of their biochemical composition, which in turn would help resolve the controversy over cargo selection and bulk flow models (Vitale and Denecke, 1999). Here, in an important step toward achieving this aim, we present biochemical and ultrastructural evidence for coatomer recruitment to donor membranes and COPI-coated vesicle budding in vitro.

RESULTS

Identification of Plant δ- and ɛ-COP Homologs and Cross-Reactivity of Antisera

Maize homologs of the coatomer components δ- and ɛ-COP were identified from the DuPont database of expressed sequence tags by homology with known sequences in GenBank. At the protein level, the 58-kD δ-COP was 88% identical and 91% similar to the previously elucidated δ-COP sequence for rice in GenBank (accession number E209222). The 31-kD maize ɛ-COP was 77% identical and 90% similar to the Arabidopsis sequence (GenBank accession number AX004238). Interestingly, both of the higher plant δ-COP sequences have greater similarity to the higher eukaryotic sequences (human δ-COP, X81197; and bovine δ-COP, X94265) than to the putative yeast δ-COP (yfr05c). Similarly, the higher plant ɛ-COP sequences were ∼45% identical to the higher eukaryotic ɛ-COP protein sequences in the public database.

The two plant COP-coated vesicle GTPases showed even greater homology with their yeast and mammalian counterparts. Thus, the Arabidopsis ARF1 sequence (M95166) encodes a protein that is 78% identical to yeast ARF1 (B36167) and 88% identical to mouse (JC4945) and human (A33283) ARF1. Arabidopsis Sar1p (M95795) is somewhat less homologous, being 64% identical to Sar1p from yeast (A33619) and 59% identical to Sar1p from mouse (S39543).

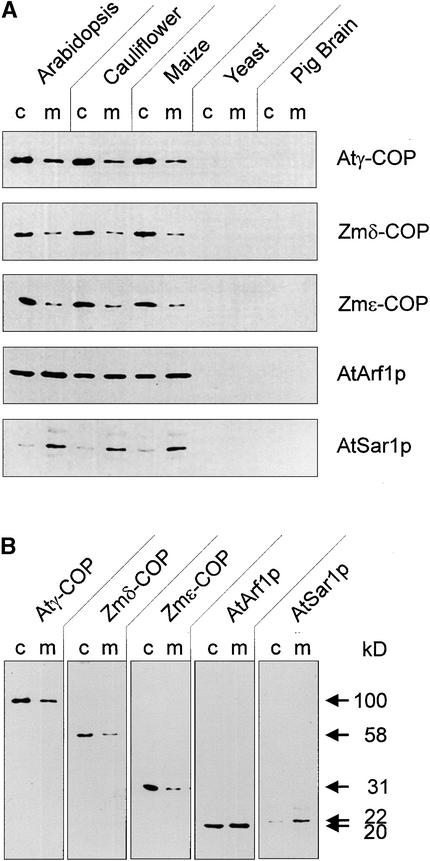

Polyclonal antibodies raised against recombinant Zmδ- and ɛ-COPs recognize polypeptides of the expected molecular masses (58 and 31 kD, respectively) in total membrane and cytosolic extracts from roots of maize and Arabidopsis as well as from cauliflower inflorescence (Figure 1A). In protein gel blots with equal amounts of protein, the signal in the cytosolic fractions was always stronger than in the membrane fractions. With the GTPase antisera, however, the signal for AtArf1p was roughly similar for both fractions, and that for AtSar1p was even stronger in the membrane fractions. A similar distribution has been reported for Sar1p in yeast (Barlowe et al., 1993). Interestingly, overexpression of Sar1p in Arabidopsis alters this relationship, such that considerably more AtSar1p is present in the cytosol than on the membranes (Bar-Peled and Raikhel, 1997).

Figure 1.

Cross-Reactivities of Antisera Raised against Recombinant Proteins Prepared from cDNA Clones for Atγ-, Zmδ-, and ɛ-COP, AtARF1p, and AtSar1p.

(A) Cytosolic proteins and total membranes from the organisms indicated were prepared as described in Methods and probed with the above antisera. Equal amounts of protein were added to each lane (30 μg). c, cytosol; m, membrane.

(B) Complete lanes and molecular masses of the Arabidopsis cytosol and membranes indicate specific recognition of a single antigen of the corresponding size for each of the above-listed antisera.

Although we had previously obtained weak cross-reactions with AtSec23p antibodies against polypeptides present in membrane or cytosolic fractions prepared from yeast and pig brain (Movafeghi et al., 1999), none of the plant COPI or GTPase antisera reacted in this way (Figure 1A). This suggests that the major antigenic determinants are localized to nonhomologous domains of COP-vesicle coat proteins. In addition, the antibodies recognized only one defined band (Figure 1B), confirming their suitability for immunocytochemistry.

Localization of Plant Coatomer

Because attempts to localize membrane-bound plant COPs by immunogold labeling of sections prepared from chemically fixed and plastic-embedded material were repeatedly unsuccessful, we applied the more sensitive Tokuyasu technique (Tokuyasu, 1986). Here, we present localization data on root tip cells from Arabidopsis and maize, the two organisms from which cDNAs were used to generate recombinant proteins and subsequently antibodies.

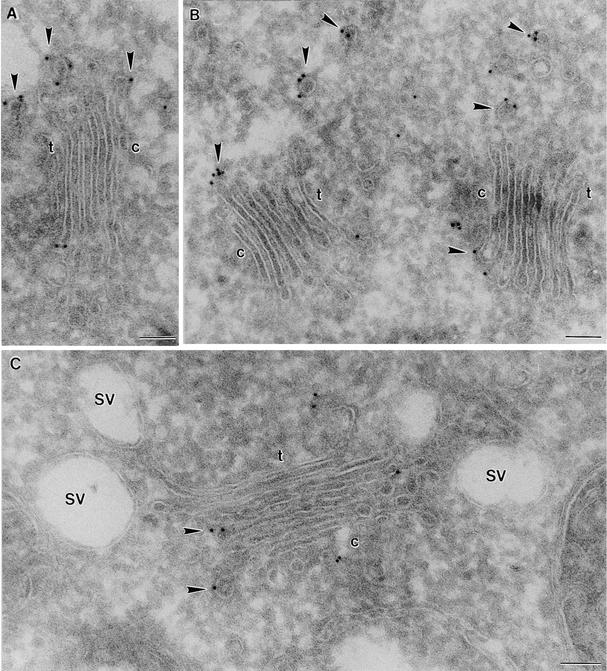

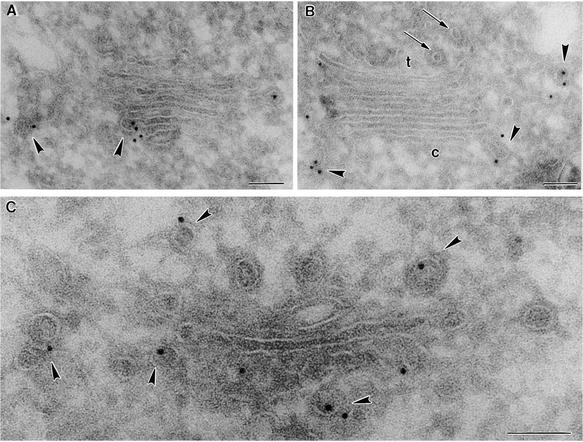

Immunogold labeling with all of the COP antisera (Atγ-COP, Zmδ-COP, Zmɛ-COP) and by Arf1p antibodies on the root tip cells of both species was highly specific: gold particles were found only on, or in the immediate vicinity of, Golgi stacks (Figures 2 to 4). Gold label was generally absent from the central portion of the cisternae, being instead restricted mostly to the rims. This peripheral labeling was often very clearly directed to small (∼60 nm in diameter) budding vesicles (see Figures 2A, 2B, 3A to 3C, and 4A). These vesicles possessed a thin (15-nm thick), irregularly shaped coat on their cytoplasmic surface and closely resembled the COPI-coated vesicles depicted by this method in mammalian cells (see, e.g., Orci et al., 1997). Profiles of similarly coated vesicles lying close to Golgi stacks were also labeled with different COP antisera (Figures 2B and 3B). Those vesicles differed from clathrin-coated vesicles, which had a thicker (25 to 30 nm) coat and a trans-Golgi position (Figure 3A). Neither the clathrin-coated vesicles nor the large, slime-filled vesicles (Figure 2C) typical of the Golgi apparatus in maize root cap cells (Mollenhauer and Morré, 1994) were labeled by COPI-immunogold.

Figure 2.

Immunogold Labeling of Cryosections with Plant COP Antibodies I.

Shown is the distribution of Atγ-COP homolog in maize roots.

(A) and (B) Golgi stacks from cells near the meristem.

(C) Golgi stack from a root cap cell.

Arrowheads point to labeled budding and released COPI-coated vesicles. c, cis-face of a Golgi stack; t, trans-face of a Golgi stack; SV, slime-containing secretory vesicle.  .

.

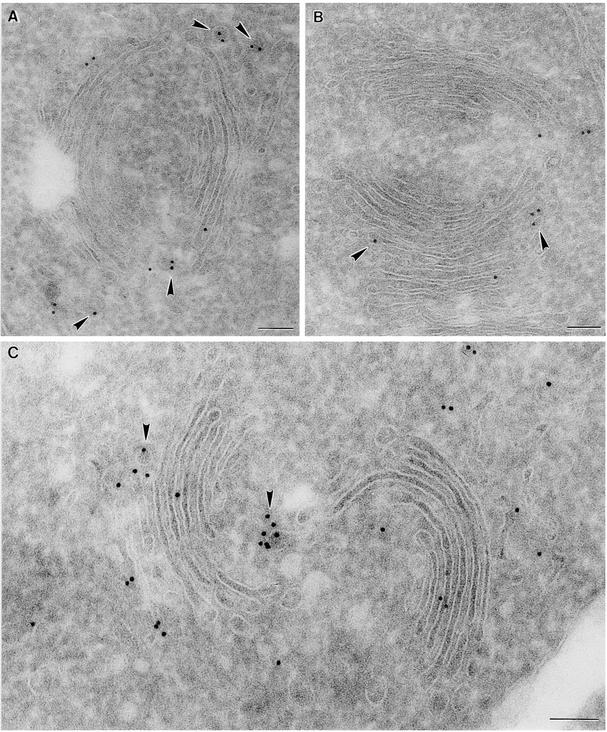

Figure 4.

Immunogold Labeling of Cryosections with Plant COP Antibodies III.

Shown is labeling of Arabidopsis root Golgi stacks.

(A) Labeling with Atγ-COP antibodies.

(B) Labeling with Zmδ-COP antibodies.

(C) Labeling with Zmɛ-COP antibodies.

Arrowheads point to budding COPI-coated vesicles.  .

.

Figure 3.

Immunogold Labeling of Cryosections with Plant COP Antibodies II.

Shown is labeling of maize root Golgi stacks from cells near the meristem.

(A) and (B) Labeling with Zmδ- and Zmɛ-COP antibodies, respectively.

(C) Labeling with AtArf1p antibodies.

Arrows point to clathrin-coated vesicles; arrowheads indicate budding COPI-coated vesicles. c, cis-face of a Golgi stack; t, trans-face of a Golgi stack.  .

.

To ascertain the localization of coatomer within the plant Golgi stack, we statistically analyzed the immunogold-COPI labeling on a large number of dictyosomes (Table 1). For this, we counted gold particles on budding vesicles still attached to cisternae as well as on putative COPI-coated vesicles lying in the areas adjacent to the polar trans-face and on the respective cis- and trans-sectors around the Golgi stack. It was immediately apparent that the majority of gold particles are associated with coated vesicles with no obvious cisternal attachment. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these vesicles may have connections to cisternae of neighboring Golgi stacks that are out of the plane of the section. Nevertheless, such “released” vesicles were rarely detected at the trans-face, and those present in the cis-sector slightly outnumbered those in the trans-sector. On the other hand, the distribution of cisternal rim COPI labeling was clearly weighted toward the cis side of the Golgi stack, such that the most label was associated with the cis-most cisternae.

Table 1.

Distribution of Immunogold Labling with Plant COP Antibodies

| Antibody | Golgi Stacks Observed |

Gold Particles on Cisternaea

|

Gold Particles on Vesiclesa

|

Total Gold Particles | Gold Particles per Stack |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Most | cis | Median | trans | TGNb | cis-Half | trans-Half | |||||

| Maize | |||||||||||

| Atγ-COP | 25 | 9 (5.2) | 8 (4.7) | 6 (3.5) | 6 (3.5) | 3 (1.8) | 78 (45.3) | 62 (36.0) | 172 | 6.88 | |

| Zmδ-COP | 25 | 8 (8.2) | 5 (5.1) | 4 (4.1) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (2.0) | 42 (42.8) | 33 (33.7) | 98 | 3.92 | |

| Zmɛ-COP | 25 | 9 (6.0) | 4 (2.7) | 4 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 68 (45.3) | 59 (33.3) | 150 | 6.00 | |

| Arabidopsis | |||||||||||

| Atγ-COP | 25 | 6 (3.3) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 95 (52.8) | 71 (39.4) | 180 | 7.20 | |

| Zmδ-COP | 25 | 5 (6.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 44 (55.0) | 26 (32.5) | 80 | 3.20 | |

| Zmɛ-COP | 25 | 10 (5.8) | 5 (2.9) | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | 99 (55.6) | 54 (31.5) | 171 | 6.84 | |

Numbers in parentheses are percentages.

TGN, trans-Golgi network.

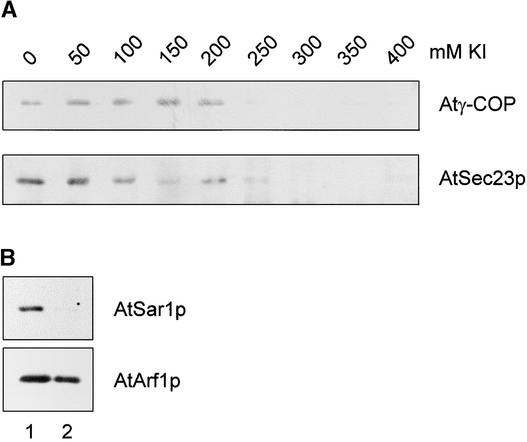

Selective Removal of Membrane-Associated COP-Vesicle Coat Proteins but Not AtArf1p Homolog

Because we had previously characterized Atγ-COP and AtSec23p homologs from cauliflower inflorescence, which has decided advantages as a potential source of plant coatomer, we continued to use this tissue in our biochemical work. To ascertain whether cytosolic nonclathrin coat protein complexes from cauliflower florets can be recruited onto endomembranes from the same tissue, we first had to determine the conditions under which endogenous COP-vesicle coat proteins could be removed from the membranes. For this, we used the chaotrope KI, which has previously been used successfully to gently dissociate nonintegral proteins from plant membranes (Hinz et al., 1997). As seen in Figure 5A, a 30-min treatment with 300 mM KI is sufficient to quantitatively dissociate both the Atγ-COP and AtSec23p homolog proteins from cauliflower membranes. The antisera prepared against these two COP-coat polypeptides recognize protein complexes in cauliflower cytosol corresponding to coatomer and the Sec23/24 dimer of the COPII coat (Movafeghi et al., 1999). The membrane fraction used was enriched in Golgi membranes, as shown previously (Movafeghi et al., 1999). Although coatomer and the COPII coat were effectively removed from cauliflower membranes through KI treatment, the two GTPases known to be involved in COP-vesicle coat protein recruitment were affected differently. The cauliflower AtArf1p homolog was not dissociated by 300 mM KI, whereas the AtSar1p homolog was completely removed from the membranes (Figure 5B). This difference most probably indicates that Arf1p, but not Sar1p, is anchored into the membrane by its myristoylated N terminus (Kahn et al., 1992).

Figure 5.

KI Dissociation of COPI- and COPII-Coat Proteins from Cauliflower Inflorescence Membranes.

(A) A Golgi-enriched fraction was treated with increasing concentrations of KI, as described in Methods, and then centrifuged to separate the membranes from the extraction medium. The pelleted membranes were then probed for the presence of coat proteins.

(B) Golgi-enriched membranes were treated as in (A), but with 300 mM KI, and then were probed with GTPase antisera. Lane 1, native membranes; lane 2, KI-stripped membranes.

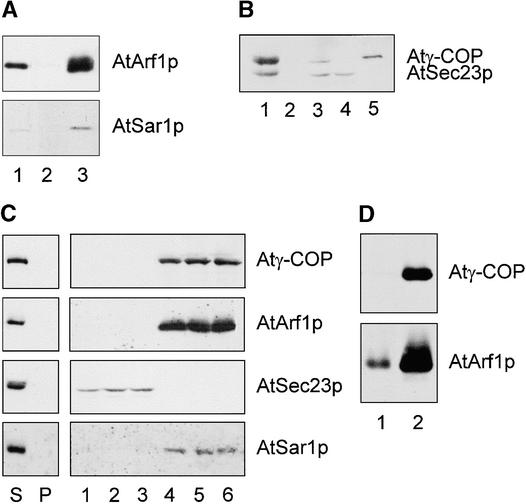

Selective Recruitment of Coatomer but not of AtSec23/24 Complex

To reconstitute the first step of vesicle budding, we incubated KI-stripped cauliflower membranes with concentrated cytosolic proteins in the presence of GTPγS and an ATP-regenerating system. Membrane recruitment was monitored by centrifugation through a sucrose step gradient in which membranes and recruited proteins are obtained in the centrifuged pellet whereas unbound proteins remain in the supernatant. These two fractions were probed for GTPases, coatomer, and the Sec23/24 complex. Our results show that both the cauliflower Arf1p and Sar1p homologs and the Sec21 homolog accumulated in the pellets as a result of the incubation (Figures 6A and 6B). In particular, all three cytosolic components were depleted from the cytosol (cf. Figure 1A cauliflower with that in Figures 6A and 6B), suggesting a highly efficient recruitment process. In contrast to coatomer, however, the Sec23/24 complex was not recruited and sedimented, even though Sar1p was (Figures 6A and 6B). The substitution of GMP-PNP (5-guanylyl-imidodiphosphate), another nonhydrolyzable analog of GTP, for GTPγS in the reaction mixture (Barlowe et al., 1994) also failed to induce recruitment of the AtSec23/24 dimer (data not shown). The lack of Sec23p sedimentation again suggests that recruitment of Sec21p is specific.

Figure 6.

In Vitro Recruitment of Cytosolic COPI-Vesicle Coat Proteins onto KI-Stripped Membranes.

(A) Recruitment of GTPases onto cauliflower membranes. KI-stripped membranes were incubated with cytosol, ATP-regenerating system, and GTPγS for 25 min at 20°C. Membranes with bound proteins were separated from unbound proteins by centrifugation. Small GTPases in each fraction were detected in a protein gel blot with specific antibodies against AtArf1p and AtSar1p. Lane 1 contains KI-stripped membranes before incubation with cytosolic proteins; lane 2, the supernatant after recruitment; and lane 3, the pelleted membranes after recruitment.

(B) Selective recruitment of coatomer onto cauliflower membranes. KI-stripped membranes were incubated as described in (A), and the sediment and supernatant proteins were screened by protein gel blotting with Atγ-COP and AtSec23p antibodies. Lane 1 contains native membranes; lane 2, KI-stripped membranes; lane 3, cytosolic proteins; lane 4, supernatant after recruitment; and lane 5, pelleted membranes after recruitment.

(C) Absence of precipitable Atγ-COP, AtArf1p, AtSec23p, and AtSar1p in cytosol only (left). Nonsaturation of coat protein recruitments onto cauliflower membranes (right). The ratio of cytosolic:membrane proteins in the recruitment assay was increased by 30% (lanes 1 and 4), 100% (lanes 2 and 5), and 200% (lanes 3 and 6) over the standard values (6 mg mL−1:0.2 mg L−1). Lanes 1 to 3 represent the supernatant fractions after recruitment; lanes 4 to 6, the corresponding pelleted membrane fractions. S represents the supernatant, P the pellet after recruitment in the absence of membranes. Membranes, medium, incubation, and other conditions were as described in (A). Antibody screening was as described in (A) and (B).

(D) Heterologous recruitment of COPI-vesicle coat proteins from cauliflower cytosol onto Golgi/ER membranes from tobacco mesophyll. Tobacco membranes were isolated as described in Methods, incubated with cauliflower cytosol, and subsequently screened with antibodies under the conditions used in (A). Lane 1 contains KI-stripped membranes; lane 2, pelleted membranes after recruitment.

To rule out nonspecific sedimentation of aggregates as an explanation for the intensifying effect on the bands observed for the membrane pellets, we repeated the experiment under the same conditions but omitting membranes. Figure 6C clearly shows that cytosol itself does not contain sedimentable coatomer, Arf1p, or Sar1p, confirming that sedimentation must have occurred as a result of membrane recruitment and sedimentation of the membrane.

To determine the saturability of the coatomer association, we performed recruitment assays with various ratios of cytosolic to membrane proteins. Even with fourfold more cytosolic protein than membrane protein, the coatomer binding was still unsaturated (Figure 6C). This indicates that the concentration of coat components in the cytosolic fraction was probably a limiting factor in the recruitment assay.

Although cauliflower cytosol represents a nearly optimal source of plant coatomer, easily transformed plants such as tobacco will be more important for answering questions as to the nature of the cargo and the direction of COP-coated vesicle transport. Accordingly, we attempted the heterologous recruitment of coatomer from cauliflower cytosol onto membranes isolated from tobacco mesophyll. We prepared a Golgi/ER fraction from tobacco leaves, stripped the endogenous coat proteins with KI, and performed an in vitro recruitment with cauliflower cytosol, as described above. Figure 6D convincingly demonstrates the interchangeability of coatomer among dicotyledonous plants.

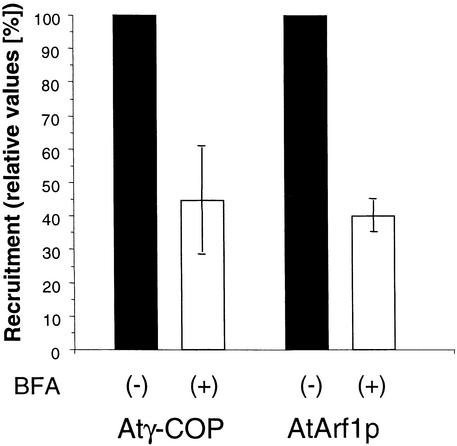

Inhibition of Coat Protein Recruitment by Brefeldin A

Treating plant and animal cells with the fungal metabolite brefeldin A (BFA) is known to inhibit anterograde protein transport and results in incorporation of the Golgi membranes and content into the ER (Klausner et al., 1992; Boevink et al., 1998). Studies on mammalian cells have established that BFA interacts with guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Helms and Rothman, 1992), thereby inhibiting Arf1p recruitment onto Golgi membranes and thus preventing coatomer attachment (Dascher and Balch, 1994). For reasons not entirely understood, there is a discrepancy between the concentrations of BFA that are effective in vivo (∼20 μM) and in vitro (200 μM) in mammalian cells (Torii et al., 1995; Peyroche et al., 1999). In plant cells, the concentration of BFA required to elicit a response in vivo usually is between 2 and 100 μM (Satiat-Jeunemaitre et al., 1995). As shown in Figure 7, concentrations >200 μM are required to inhibit the in vitro recruitment of AtArf1p and coatomer. These results also confirm the specificity of the recruitment reaction.

Figure 7.

BFA Inhibits Recruitment of Coatomer and AtArf1p in Cauliflower Recruitment Assay.

Bound coatomer/Arf1p in control and BFA-treated samples was quantified by densitometry of protein gel blots of samples of equal volume. Shown are the results of four separate experiments whose average is given as columns; the error bars represent the extent of the variation between experiments. (+) denotes the presence of 300 μM BFA and (−) the absence of BFA in the incubation media.

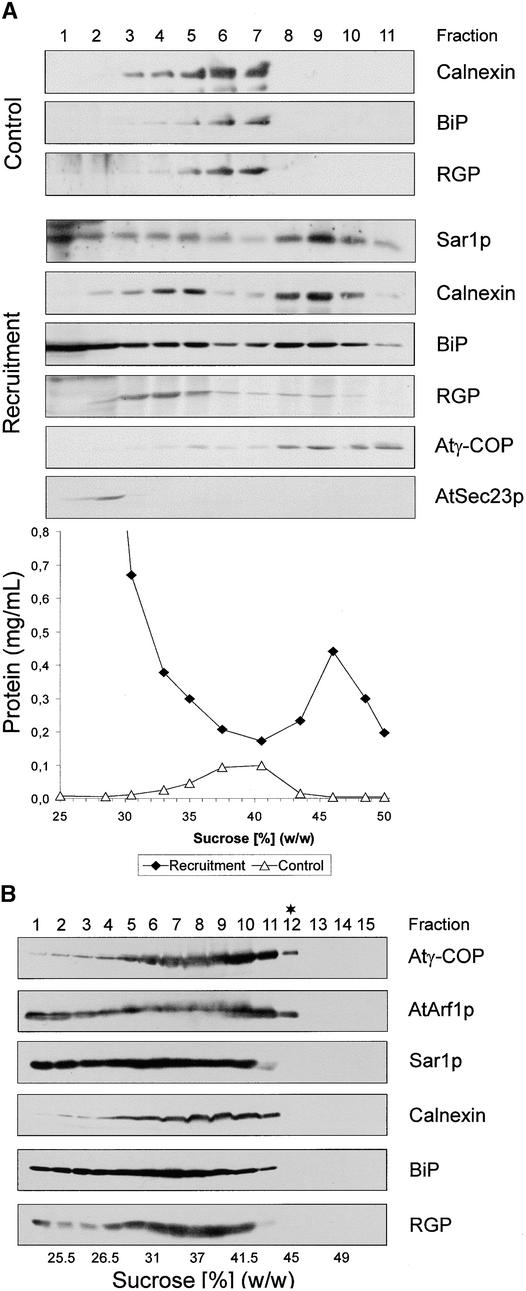

COPI-Coated Vesicle Formation in Vitro

KI-stripped Golgi-enriched membrane fractions from cauliflower inflorescence have a higher isopycnic density in sucrose after being incubated with cytosolic proteins in the presence of GTPγS (Figure 8A). Compared with control membranes exposed to buffer and GTPγS, incubation with cytosolic proteins led to a density increase of 8 to 10% (sucrose equivalents). This shift in density could be attributed to the recruitment of AtArf1p and coatomer onto Golgi membranes. Although the AtSec23p homolog stayed in the overlay, the attachment of AtSar1p homolog to the ER could also result in such a shift. Indeed, protein gel blots with antisera against suitable marker proteins showed that Golgi membranes, as judged by the Golgi marker reversibly glycosylated protein (RGP) (Movafeghi et al., 1999) and the ER markers binding protein (BiP) and calnexin, shifted to greater densities. However, we considered recruitment of the AtSar1p homolog to be insufficient to cause such a massive increase in isopycnic density of the ER. Instead, we surmised that this shift might have resulted from the attachment of Golgi-derived COPI-coated vesicles, which, because of their Arf1p-bound GTPγS, cannot dissociate their coat and are therefore unable to fuse. This, in fact, was the basic premise that led to the first successful isolation of COPI-coated vesicles from mammalian cells (Malhotra et al., 1989).

Figure 8.

Detection of in Vitro–Formed COPI-Coated Vesicles.

(A) Recruitment of coatomer onto KI-stripped membranes leads to an increase in their equilibrium density. Stripped membranes from cauliflower inflorescence were incubated in the absence or presence of cauliflower cytosolic proteins, as described for Figure 6A. The incubation mixtures were then layered onto sucrose density gradients and centrifuged to equilibrium, as described in Methods. Fractions were screened with antibodies against ER (calnexin, BiP), Golgi (RGP), and COPI/COPII coat proteins (Atγ-COP, AtSec23p). As depicted, stripped membranes banded at densities ∼10% (w/w) less than those at which the recruited membranes did.

(B) Isolation of COPI-coated vesicles. KI-stripped cauliflower membranes were incubated with cauliflower cytosol under standard conditions, extracted with high-salt reagent (250 mM KCl) for 30 min at 4°C, and centrifuged at 30,000g; the membranes in the supernatant were subjected to isopcynic sucrose density gradient centrifugation as in (A). Equal-volume fractions were then monitored in protein gel blots with the antisera described above. The asterisk denotes the putative COPI-coated vesicle–containing fraction used for Figure 9.

To release bound COPI-coated vesicles, we therefore treated recruited cauliflower membranes with 250 mM KCl. The high-salt mixture was then centrifuged at 30,000g for 30 min to remove most of the ER and Golgi membranes. Membranes in the 30,000g supernatant were subsequently subjected to an isopycnic sucrose density gradient centrifugation. As shown in Figure 8B, despite the precentrifugation at 30,000g, considerable amounts of Golgi and ER markers were still carried over in the high-salt extract. Nevertheless, at least one fraction (no. 12, at 45% sucrose) exhibited a clear signal in protein gel blots with AtArf1p and Atγ-COP antisera; this density corresponded to that reported for mammalian COPI-coated vesicles (42 to 45% [w/w] sucrose) (Malhotra et al., 1989). Fraction 12 did not, however, contain detectable amounts of BiP, calnexin, or Golgi (RGP) proteins. Therefore, we further analyzed this fraction by negative staining as well as by immunogold negative staining because the very low amounts of protein precluded examination by sectioning procedures.

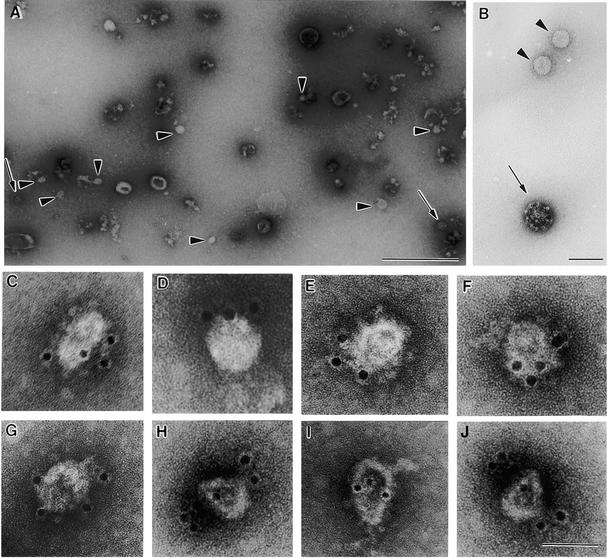

For the immunogold labeling, we used Zmɛ-COP antibodies, since ɛ-COP is more exposed at the surface of coatomer than are the other COPs (Duden et al., 1998). Using this method of visualization, we found that the fraction was not homogeneous. In addition to small numbers of 50- to 60-nm-diameter vesicles, fraction 12 contained undefined particle aggregates and small membrane fragments as well as clathrin-coated vesicles (Figures 9A and 9B). However, only the 50- to 60-nm-diameter non-clathrin-coated vesicles reacted specifically with Zmɛ-COP antibodies (Figures 9C to 9J), confirming their identity as COPI-coated vesicles.

Figure 9.

Immunogold Negative Staining of the Contents of Fraction 12 from the Gradient Shown in Figure 8B.

(A) Overview of normal negative staining. Putative COPI-coated vesicles are indicated with arrowheads, clathrin-coated vesicles with arrows.

(B) Comparison of clathrin- and COP-coated vesicles. Arrows and arrowheads are as in (A).

(C) to (J) Gallery of negatively stained putative COPI-coated vesicles decorated with gold-coupled Zmɛ-COP antibodies.

;

;  ;

;  .

.

Heterologous Recruitment of Cauliflower Coatomer onto Tobacco ER/Golgi Membranes

To rule out that the vesicles detected in Figure 9 could have originated from the cauliflower cytosol, we prepared a Golgi/ER fraction from tobacco plants that overproduced the soluble secretory marker α-amylase tagged to the C-terminal tetrapeptide HDEL (Crofts et al., 1999). To maximize vesicle production and to avoid nonspecific recruitment of coatomer to naked membranes, we did not strip the ER/Golgi fraction with KI but incubated it directly with cauliflower cytosol in the presence or absence of ATP, the ATP-regenerating system, and GTPγS.

After the induction, the membranes were purified by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose layer onto a 60% sucrose cushion to remove unbound coatomer. Membranes were then recovered, stripped with 250 mM KCl to release COPI-coated vesicles, and separated through a 42% sucrose layer onto a linear sucrose gradient (43 to 50%). We omitted the precentrifugation at 30,000g used in the experiment shown in Figure 8B to obtain a relative distribution of cargo in donor membranes and recruited membranes at greater densities throughout the whole density range. Figure 10A clearly shows that in the presence of ATP, the ATP-regenerating system, and GTPγS, Sec21p was recruited and recovered in a high-density membrane fraction that also contained the most α-amylase–HDEL and calreticulin. In the absence of ATP/GTP (Figure 10B), only small amounts of these three proteins were detected in that fraction. This result confirms the dependence of recruitment on ATP/GTP; it also rules out the possibility that the dense membranes were of cytosolic origin, because α-amylase activity was present only in tobacco membranes. The formation of nonspecific coatomer aggregates is also excluded because Atγ-COP was detected in the middle of the gradient and not at the bottom, where any sediments would have been found. These data set the stage for future experiments with respect to the specificity of cargo recruitment.

Figure 10.

Heterologous in Vitro Induction of COPI-Coated Vesicles from Cauliflower Cytosol and Tobacco Membranes from Plants Expressing α-Amylase–HDEL.

(A) Incubation performed in the presence (+) of ATP/GTPγS. The histogram represents the profile of α-amylase activity. The protein gel blots of the corresponding fractions document the distributions of calreticulin and Atγ-COP in relation to α-amylase activity.

(B) Incubation performed in the absence (−) of ATP/GTPγS.

All incubations and membrane separations were as given in Figure 8B. Activity measurements were performed in triplicate; error bars represent the extent of variation.

DISCUSSION

COPI-Coated Vesicles and the Plant Golgi Apparatus

Several morphological and biochemical characteristics differentiate the plant Golgi apparatus from its counterpart organelle in mammalian cells and yeast (Andreeva et al., 1998; Dupree and Sherrier, 1998; Robinson and Hinz, 1999). Many of these distinguishing features relate to the predominant function of the plant Golgi apparatus in synthesis of cell wall polysaccharides, especially during cell division, and to the necessity for directing proteins to two rather than one vacuolar compartment (Robinson and Hinz, 1997, 1999). In addition, the individual Golgi stacks of the plant cell appear to be in continuous movement throughout the cytoplasm along an anastomosing network of ER/actin filaments (Boevink et al., 1998) and are generally dispersed throughout the cytoplasm. In mammalian cells, however, the Golgi is restricted to a defined position near the nucleus. Despite these differences, plant cells are generally assumed not to differ fundamentally from other eukaryotes in terms of ER–Golgi transport, intra-Golgi transport, and recycling (Andreeva et al., 1998; Dupree and Sherrier, 1998).

Here, we have established that COPI-coated vesicles in plants are predominantly formed by the cis- and medial Golgi cisternae, although they are also detected at the margins of trans-cisternae. Coatomer is also localized to ERGIC in mammalian cells (Oprins et al., 1993; Griffiths et al., 1995; Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999). This post-ER, pre-Golgi compartment has been described morphologically as consisting of vesicular tubular clusters (Bannykh and Balch, 1998) and is considered to be formed by the homotypic fusion of COPII-coated vesicles (Aridor et al., 1995; Scales et al., 1997). The COPI-coated vesicles formed from this compartment are believed to concentrate membrane proteins destined for recycling to the ER (Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999). Although plant cells have no obvious structural homolog to ERGIC, it is perhaps significant that the cis-most elements of the plant Golgi apparatus often appear as a discontinuous cisterna; this may reflect a fusion site for ER-derived COPII-coated vesicles.

Coatomer Recruitment and COPI-Coated Vesicle Formation

COPI-coated vesicle formation in mammalian cells depends on two cytosolic factors: the GTPase Arf1p and coatomer (Orci et al., 1993; Palmer et al., 1993). For coatomer recruitment, Arf1p is in a GTP-bound form, but it is reconverted to the GDP form by a GTPase-activating protein, GAP (Ostermann et al., 1993), at which point coatomer is released. Interestingly, Arf-GAP activity is stimulated by coatomer (Goldberg, 1999). GTP hydrolysis is required for coat protein dissociation (Tanigawa et al., 1993), and the inhibition of GTP hydrolysis by GTPγS blocks uncoating and leads to the accumulation of COPI-coated vesicles in vitro (Melançon et al., 1987; Malhotra et al., 1989). Importantly, high-salt treatment of Golgi membranes does not dissociate anchored Arf1p but does remove Arf-GAP and is thought to enhance even more accumulation of COPI-coated vesicles (Ostermann et al., 1993). For this reason, we used KI-stripped instead of native membranes in our first recruitment experiments.

KI-stripped cauliflower membranes still possessed an AtArf1p homolog but lacked coatomer, and incubation of these membranes with concentrated cauliflower cytosol in the presence of GTPγS led to the binding of coatomer. This recruitment was selective: under the same conditions, the AtSec23/24 dimer homolog of COPII-coated vesicles, also shown to be present in cauliflower cytosol (Movafeghi et al., 1999), did not attach. Recruitment was also specific, as judged by the BFA inhibition of both Arf1p and coatomer recruitment.

Why the AtSec23/24p homolog was not recruited is unclear. Although the cauliflower Golgi fraction used might have had insufficient COPII budding sites in the ER membranes to support a COPII coat recruitment, we think it more likely that the explanation involves an aspect of the crucial role Sar1p plays in the production of COPII-coated vesicles (Schekman and Orci, 1996). As with COPI-coated vesicles, binding of Sar1p precludes the recruitment of the Sec23/24 dimer (Barlowe et al., 1994; Aridor et al., 1998); unlike Arf1p, however, Sar1p does not become anchored in the membrane and is released after the assembly of the COPII coat has been completed. Because 80% of Sar1p is membrane bound (Figure 1; for yeast, see also Barlowe et al., 1993), the amount of Sar1p homolog in the cauliflower cytosol may be insufficient to support recruitment of Sec23/24 dimer.

The shift in equilibrium density of KI-stripped cauliflower membranes after incubation with cytosol and GTPγS points to a massive recruitment of coat proteins. This will increase the density of the Golgi membranes but perhaps also indirectly that of the ER. Golgi-derived COPI-coated vesicles formed in the presence of GTPγS may dock onto their target membranes (in part, the ER), but they cannot fuse with that membrane because of their inability to uncoat. As shown by Malhotra et al. (1989), high-salt treatment causes the release of attached, unfused COPI-coated vesicles, which can then be separated from the donor/acceptor membranes by a combination of sequential differential and sucrose density centrifugations. We used conditions similar to those of Malhotra et al. (1989) and were able to visualize COPI-coated vesicles, as defined by labeling with anti–Zmɛ-COP antibodies. However, we could not obtain a homogeneous COPI-coated vesicle fraction as reported by Malhotra et al. (1989), who used a relatively pure rabbit liver Golgi fraction. The cisternal elements of the latter were easily sedimented at low-speed centrifugation (microfuge), whereas in our experiments, centrifugation at 30,000g did not achieve this. Because of their dispersed nature, plant Golgi membranes are difficult to isolate in large quantities, a property that remains an obstacle for future research with purified components.

The interaction between coatomer and dilysine motifs in the cytosolic domain of type I ER membrane proteins has formed the basis for the notion that COPI-coated vesicles are involved in retrograde transport from the Golgi apparatus (Cosson and Letourneur, 1994; Letourneur et al., 1994). Our in vitro data neither confirm nor exclude this possibility, and we point out that the identification of potential cargo molecules in COPI-coated vesicles induced in vitro is made inherently difficult because of a peculiarity of the conditions under which they are formed. Nickel et al. (1998) and Malsam et al. (1999) showed that the uptake of anterograde and retrograde integral membrane reporter molecules into COPI-coated vesicles was markedly diminished when they were formed in the presence of GTPγS rather than GTP. Indeed, Malsam et al. (1999) went so far as to suggest that, when GTP hydrolysis is prevented, coatomer binds instantaneously, leading to the release of cargo-free COPI-coated vesicles. In addition, in vivo experiments with a GTPase-deficient ARFI mutant suggest that when GTP hydrolysis is prevented, cargo-free COPI-coated vesicles are produced (Pepperkok et al., 2000). This would mean that the in vitro approach to determining the cargo content of plant COPI-coated vesicles can be of value only when assays of the induction of COPI-coated vesicles are performed in the presence of GTP. However, such vesicles are inherently more unstable than those produced in the presence of GTPγS.

Interchangeability of Coatomer between Different Plant Species

The ability to visualize the in vitro–induced COPI-coated vesicles encouraged us to test whether cauliflower coatomer could be recruited onto membranes of other origins, such as tobacco, which is more amenable to genetic manipulation. In addition, to confirm the specificity of the in vitro reaction, we tested whether in vitro vesicle budding would be dependent on ATP and GTP. We readily established that this specificity exists and demonstrated that heterologous recruitment of coatomer to membranes from another plant species is possible. In addition, we showed that retrograde transport markers are enriched in the fraction that contains the greatest amounts of recruited Atγ-COP. Our results appear to contrast with those obtained by Pepperkok et al. (2000), who demonstrated that GTP hydrolysis is crucial for cargo loading into COPI-coated vesicles. However, those investigators studied membrane-spanning cargo molecules, whereas we focused on soluble cargo molecules. Nevertheless, whether the cosedimentation of Atγ-COP and soluble retrograde cargo was indeed due to the presence of cargo in COPI-coated vesicles remains to be shown. We cannot exclude the possibility that COPI-coated vesicles attached to ER membranes are responsible for the density shift. Further work will be necessary to clarify this point.

Golgi →ER Protein Recycling

We found our coatomer labeling predominated at the cisternal rims, especially the cis-cisternae, which may be analogous to the observations of Martinez-Menarguez et al. (1999), who localized COPI coats to the tips of ERGIC tubules in pancreatic cells. This might indicate that the cis-most elements of the plant Golgi stack are the plant ERGIC equivalent—a proposal supported by the finding that saturation of ER retention by overexpression of the ER resident protein calreticulin does not result in the accumulation of intracellular endoH-resistant forms of calreticulin, even though the secreted portion is fully modified by Golgi enzymes during transit (Crofts et al., 1999). These results have been interpreted as indicating the existence of a highly efficient cis-Golgi–based retrieval mechanism for ER residents and are supported by the present observations, in which a putative COPI-coated vesicle–containing fraction was shown to contain calreticulin. Pagny et al. (2000), working with suspension-cultured tobacco BY-2 cells, reached a different conclusion, however. They claim that normal ER residents such as calreticulin are actively excluded from ER export and are therefore not recycled from the Golgi apparatus. On the other hand, foreign proteins expressed with an HDEL C-terminal tetrapeptide do leave the ER and may be retrieved even from later Golgi compartments than the cis-cisternae.

Relevant to this controversy is the subcellular distribution of the plant H/KDEL receptor ERD2p. According to the data of Boevink et al. (1998), an ERD2-GFP construct in tobacco mesophyll is distributed throughout the Golgi stack and is detectable in both the central and peripheral portions of the cisternae. Those results were obtained from cells overexpressing ERD2-GFP, however, and such overexpression or the attachment of GFP, or both, might influence the localization of the receptor. Localization of ERD2 in wild-type cells may well be different, possibly even restricted to the cis-cisternae. In the normal physiological state, recycling soluble ER residents by way of the ERD2 pathway may play only a minor role in retention. Hence, retrograde transport of soluble cargo in COPI-coated vesicles may be detectable only in artificial situations in which recycling is increased, that is, during ER stress or in transgenic plants overproducing retrograde cargo molecules such as α-amylase–HDEL or calreticulin.

METHODS

Material

Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var botrytis) inflorescences (10 to 15 cm in diameter) were excised from greenhouse-grown plants, and the woody stalk tissue was removed. Arabidopsis thaliana var Columbia seeds were surface sterilized, transferred to Erlenmyer flasks containing Murashige and Skoog basal medium (no. 5519; Sigma), and shaken at 120 rpm under weak light at 25°C. Seven- to 10-day-old seedlings were harvested. After 24 hr of imbibition under running tap water, maize (Zea mays var mutin) seeds were sown on moist filter paper and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 4 to 6 days. Commercially obtained bakers' yeast (Saccharomyces cereviseae) was cultured in Erlenmeyer flasks, as described by Movafeghi et al. (1999), and the cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation. Pig brain was purchased at a local slaughterhouse, transported on ice, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until required.

Generation of Recombinant Proteins and Preparation of Antisera

COPI Proteins

The open reading frames of maize δ- and ɛ-COPs (coat proteins) (GenBank accession numbers AF216582 and AF216583, respectively) were cloned by standard procedures into the NdeI/BamHI site of the pET-15b vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and expressed in Escherichia coli (strain BL21DE3; 200-mL cultures, 1 hr, 30°C). The His-fusion proteins were recovered in the insoluble pellet. The inclusion bodies were washed and solubilized as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). The recombinant proteins were purified by binding and eluting from a 1-mL HisBand resin column (Novagen) under denaturing conditions, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The identities of the purified proteins were confirmed by N-terminal sequencing after separation by SDS-PAGE and transferring to polyvinylidenedifluoride, as given by Matsudaira (1990). Polyclonal antibodies in rabbits were prepared commercially (Covance, Denver, PA).

GTPases

The AtSar1p encoding region (GenBank accession number M95795) was removed from pJPT1 by cutting with BamHI, subjecting to Klenow treatment, cutting with BglII, and purifying by agarose gel electrophoresis. pGEX-3X was cut with EcoRI, Klenow treated, and cut with BamHI, and the excised fragment ligated onto it. This was followed by dephosphorylation with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase, yielding plasmid pPP2. To specifically amplify the Arf1p coding region (GenBank accession number M95166), we prepared total first-strand cDNA from 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings, as described previously (Denecke et al., 1995). To amplify this cDNA by the polymerase chain reaction, we used GATCAGGGATCCGGTTGTCATTCGG as the sense primer and GCTAGAATTCCATCTATGCCTTGCTTGCGAT as antisense primer in 5′ to 3′ direction. This allowed generation of a BamHI site at the N terminus and an EcoRI site at the C terminus. The amplified fragment obtained was cut with these two restriction enzymes, purified on gel, and ligated into pGEX-3x that had been previously cut with BamHI and EcoRI; this yielded pPP4. Production and purification of recombinant Sar1 and ARF1 recombinant glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins as well as the commercial preparation of antisera were performed as previously described (Movafeghi et al., 1999).

Purification of IgGs

IgGs were separated from crude serum on a protein A–Sepharose CL-4B (no. P3391; Sigma) column and eluted with 100 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.9, as given by Harlow and Lane (1988).

Preparation of a Cytosol Fraction

Five hundred grams of cauliflower floret tissue was homogenized in 500 mL of prechilled medium A (25 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 8.0, 300 mM sucrose, 500 mM KCl, 3 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM o-phenanthroline, 1.4 μg L−1 pepstatin, 0.5 μg L−1 leupeptin, 2 μg L−1 aprotinin, and 1 μg mL−1 trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-(4-guanido)-butane [E-64]) by using a Waring Blendor in three 15-sec bursts. The slurry was then passed through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem) and four layers of gauze. After precentrifugation at 10,000g for 15 min, cell membranes were removed by a further centrifugation at 150,000g for 1 hr. Ammonium sulfate (final concentration, 65% saturated) was then added to the supernatant, and the precipitated proteins were recovered by centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 min. After the pellet was redissolved in 90 mL of medium A, the protein mixture was subjected to dialysis five times (25 min each) against 2 L of medium B (25 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.2, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 10% [v/v] glycerin). Subsequently, the protein solution was centrifuged at 150,000g for 1 hr before subdivision into 2-mL aliquots that were then frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before use. Ordinarily, a standard cytosol preparation had a protein concentration of 17 to 20 mg mL−1.

Preparation of a Golgi-Enriched Fraction and KI Dissociation of Coat Proteins

Thirty-five grams of cauliflower floret tissue was homogenized in 35 mL of prechilled medium A (but at pH 7.5 and minus the KCl and EDTA) by hand-grinding for 10 min with a mortar and pestle. The homogenate was passed through two layers of Miracloth and four layers of gauze and precentrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. The supernatant (25 mL) was then layered onto a sucrose step gradient (5 mL of 30% [w/w] sucrose and 5 mL of 35% [w/w] sucrose) made up in medium C (25 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.2, 20 mM KCl). After centrifugation at 100,000g for 3 hr in a swinging bucket rotor, the membranes collecting at the 30/35% interphase were removed, diluted with an equal volume of medium C, and recentrifuged at 70,000g for 20 min. (Previous measurements of marker enzymes and proteins had indicated that cauliflower Golgi membranes equilibrated at sucrose densities between 30 and 35% [Movafeghi et al., 1999].) Membrane pellets were resuspended in 2 to 4 mL of 300 mM KI (dissolved in medium C containing 200 mM sucrose) and rotated for 45 min at 4°C before being recentrifuged at 70,000g for 20 min. The stripped membranes were resuspended in medium C. The same procedure was used to isolate Golgi membranes from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum var SR1) mesophyll, except that 10 mM ascorbic acid, 2 mM sodium metabisulfite, and 1 g L−1 polyvinylpyrrolidone were added to medium C.

Recruitment Assays

A standard recruitment assay contained in a total volume of 4 mL the following components: 0.8 mg of membranes, 24 mg of cytosolic proteins, 50 μM ATP, 250 μM UTP, 20 μM GTPγS, 200 μM DTT, 28 units of creatine kinase, 2 mM creatine phosphate, and medium C containing 200 mM sucrose. The recruitment was started by adding the membranes, and the assay tubes were gently shaken at 20°C for 25 min. At the end of the recruitment, the contents of each assay tube were layered onto sucrose step gradients (4 mL of 20% [w/w] sucrose and 4 mL of 25% [w/w] sucrose) and centrifuged at 100,000g for 3 hr. The soluble overlay and the pellet were separated, and the soluble proteins were recovered by precipitation with chloroform/methanol according to Wessel and Flügge (1984).

Isolation of COPI-Coated Vesicles

The contents of an 8-mL recruitment mixture (see above) was layered onto two sucrose step gradients (4 mL of recruitment mixture onto 7 mL of 20% [w/w] sucrose and 1 mL of 55% [w/w] sucrose) and centrifuged at 100,000g for 3 hr. The membranes collecting at the interface were diluted with an equal volume of a solution of 500 mM KCl, 300 mM sucrose, and 25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.2, and shaken for 45 min at 4°C. The high-salt mixture was then centrifuged at 30,000g for 30 min, and the supernatant (4 mL) was layered over a sucrose step gradient (8 mL, consisting of five 1.6-mL steps of 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60% [w/w] sucrose dissolved in medium C containing 2.5 mM magnesium acetate), which was then centrifuged at 100,000g for 10 hr. The 0.5-mL fractions collected were analyzed by protein gel blots and negative staining (see below).

Gel Electrophoresis, Protein Gel Blotting, and Protein Determination

Membrane and cytosolic proteins were separated on 10 or 12% minigels by standard procedures, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose by using a semidry blotting apparatus, and visualized with an ECL kit (Amersham Life Sciences, Braunschweig, Germany). The primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: Atγ-COP, 1:2500; AtSec23p, 1:2500; Zmδ-COP, 1:5000; Zmɛ-COP, 1:10,000; AtARF1p, 1:2500; AtSar1p, 1:2500; binding protein (BiP), 1:10,000; calnexin, 1:10,000; and RGP, 1:20,000 (supplied by Dr. K. Dhugga, Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Johnston, IA). Bands on the ECL film were quantified by using the BASYS gel-analyzing system (BioTec Fisher, Reiskirchen, Germany). Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford (1976).

Cryosectioning and Immunogold Labeling

Root tips 2 mm long were excised, immersed in a primary fixative, and infiltrated with sucrose, as described previously (Hinz et al., 1999). The root tips were then mounted onto specimen stubs, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and cut into ultrathin sections at −120°C with a Leica UCT microtome (Leica, Bensheim, Germany). Frozen sections were picked up as described by Liou et al. (1996) and transferred to Formvar-coated nickel grids stabilized with carbon.

Immunogold labeling consisted of the following steps: three 5-min washes in 20 mM glycine/PBS; blocking for 5 min in 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS; 1-hr incubation at room temperature with primary antibody in 1% BSA in PBS; three 5-min washes in 0.1% BSA in PBS; 1-hr incubation at room temperature with gold-coupled secondary antibody in 1% PBS; one 5-min wash in 0.1% BSA; three 5-min washes in PBS; and five 2-min washes in double-distilled water. This was followed by a staining procedure consisting of a 5-min incubation with uranyl acetate/oxalate (in 150 mM oxalic acid, adjusted to pH 7.0 with ammonium hydroxide), two 2-min washes in double-distilled water, and a 5-min incubation in cold 1.8% (w/v) methyl cellulose containing aqueous 0.4% (w/v) uranyl acetate, pH 4.0.

The primary antibodies and their dilutions were as follows: Atγ-COP, 1:200; Zmδ-COP, 1:100; Zmɛ-COP, 1:200; Arf1p, 1:500. Secondary antibodies (goat anti–rabbit IgG) coupled to 10-nm-diameter particles of gold were obtained from BioCell (Cardiff, UK) and diluted 1:30 in PBS containing 1% BSA.

Negative Staining and Immunogold Negative Staining

Negative staining was performed on carbon-coated mica, as described previously (Robinson et al., 1987). Immunogold negative staining was performed as described by Drucker et al. (1995). The membranes in a 10-μL aliquot were allowed to attach to the surface of a carbon-coated Formvar grid and were then stabilized by a 10-sec fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, before exposure to the primary antibody solution (Zmɛ-COP diluted 1:1000) for 1 hr. After washing and blocking, the samples were exposed for 45 min to rabbit IgGs (diluted 1:100) coupled to 10-nm-diameter gold particles before staining for 5 sec in aqueous 3% uranyl acetate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christel Rühling for her technical support in cryosectioning. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 523 and GK “Signalvermittelter Transport von Proteinen und Vesikeln”) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. A.M. was the recipient of a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture and Higher Education of Iran.

References

- Andreeva, A.V., Kutuzov, M.A., Evans, D.E., and Hawes, C.R. (1998). The structure and function of the Golgi apparatus: A hundred years of questions. J. Exp. Bot. 49, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., Bannykh, S.I., Rowe, T., and Balch, W.E. (1995). Sequential coupling between COPII and COPI vesicle coats in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J. Cell Biol. 131, 875–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., Weissman, J., Bannykh, S.I., Nuoffer, C., and Balch, W.E. (1998). Cargo selection by the COPII budding machinery during export from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 141, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannykh, S.I., and Balch, W.E. (1998). Selective transport of cargo between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi compartments. Histochem. Cell Biol. 109, 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., and Schekman, R. (1993). SEC12 encodes a guanine nucleotide exchange factor essential for transport vesicle formation from the ER. Nature 365, 347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., d'Enfert, C., and Schekman, R. (1993). Purification and characterization of SAR1p, a small GTP-binding protein required for transport vesicle formation from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 873–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., Orci, L., Yeong, T., Hosobuchi, M., Hamamoto, S., Salama, N., Rexach, M.F., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., and Schekman, R. (1994). COP II: A membrane coat formed by sec proteins that drives vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 77, 895–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled, M., and Raikhel, N.V. (1997). Characterization of AtSec12 and AtSar1, proteins likely involved in endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi transport. Plant Physiol. 114, 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boevink, P., Oparka, K., Santa Cruz, S., Martin, B., Betteridge, A., and Hawes, C. (1998). Stacks on tracks: The plant Golgi apparatus traffics on an actin/ER network. Plant J. 15, 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremser, M., Nickel, W., Schweikert, M., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., Hughes, C.A., Söllner, T.H., Rothman, J.E., and Wieland, F.T. (1999). Coupling of coat assembly and vesicle budding to packaging of putative cargo receptors. Cell 96, 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardin, P., Paris, S., Antonny, B., Robineau, S., Béraud-Dufuor, S., Jackson, C.L., and Chabre, M. (1996). A human exchange factor for ARF contains Sec7- and pleckstrin-homology domains. Nature 384, 481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson, P., and Letourneur, F. (1994). Coatomer interaction with di-lysine endoplasmic reticulum motifs. Science 263, 1629–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts, A.J., Leborgne-Castel, N., Hillmer, S., Robinson, D.G., Phillipson, B., Carlsson, L., Ashford, D.A., and Denecke, J. (1999). Saturation of the endoplasmic reticulum retention machinery reveals anterograde bulk flow. Plant Cell 11, 2233–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher, C., and Balch, W.E. (1994). Dominant inhibitory mutants of ARF1 block endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport and trigger disassembly of the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 1437–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecke, J., Carlsson, L., Vidal, S., Ek, B., Höglund, A.-S., Van Zeijl, M., Sinjorgo, K.M.C., and Palva, E.T. (1995). The tobacco homolog of mammalian calreticulin is present in protein complexes in vivo. Plant Cell 7, 391–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Enfert, C., Geusse, M., and Gaillardin, C. (1992). Fission yeast and a plant have functional homologues of the Sar1 and Sec12 proteins involved in ER to Golgi traffic in budding yeast. EMBO J. 11, 4205–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, M., Herkt, B., and Robinson, D.G. (1995). Demonstration of a β-type adaptin at the plant plasma membrane. Cell Biol. Int. 19, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Duden, R., Griffiths, G., Frank, R., Argos, P., and Kreis, T.E. (1991). β-COP, a 110 kDa protein associated with non-clathrin-coated vesicles and the Golgi complex, shows homology to β-adaptin. Cell 64, 649–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duden, R., Hosobuchi, M., Hamamoto, S., Winey, M., Byers, B., and Schekman, R. (1994). Yeast beta- and beta'-coat proteins (COP): Two coatomer subunits essential for endoplasmic reticulum–to–Golgi protein traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24486–24495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duden, R., Kajikawa, L., Wuestehube, L., and Schekman, R. (1998). ɛ-COP is a structural component of coatomer that functions to stabilize α-COP. EMBO J. 17, 985–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, P., and Sherrier, D.J. (1998). The plant Golgi apparatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1404, 259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulstich, D., Auerbach, S., Orci, L., Ravazzola, M., Wegehingel, S., Lottspeich, F., Stenbeck, G., Harter, C., Wieland, F.T., and Tschochner, H. (1996). Architecture of coatomer: Molecular characterization of delta COP and protein interactions within the complex. J. Cell Biol. 135, 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, J. (1999). Structural and functional analysis of the ARF1–ARFGAP complex reveals a role for coatomer in GTP hydrolysis. Cell 96, 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, G., Pepperkok, R., Krijnse-Locker, J., and Kreis, T.E. (1995). Immunocytochemical localization of β-COP to the ER–Golgi boundary and the TGN. J. Cell Sci. 108, 2839–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Kuge, S., Kuge, O., Orci, L., Amherdt, M., Ravazzola, M., Wieland, F.T., and Rothman, J.E. (1994). En bloc incorporation of coatomer subunits during the assembly of COP-coated vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 124, 883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, E., and Lane, D. (1988). Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press). pp. 309–312.

- Harter, C. (1999). COPI proteins: A model for their role in vesicle budding. Protoplasma 207, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, C., and Wieland, F.T. (1998). A single binding site for di-lysine retrieval motifs and p23 within the γ-subunit of coatomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11649–11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J.B., and Rothman, J.E. (1992). Inhibition by brefeldin A of a Golgi membrane enzyme that catalyzes exchange of guanine nucleotide bound to ARF. Nature 360, 352–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, G., Menze, A., Hohl, I., and Vaux, D. (1997). Isolation of prolegumin from developing pea seeds: Its binding to endomembranes and assembly into prolegumin hexamers in the protein storage vacuole. J. Exp. Bot. 48, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, G., Hillmer, S., Bäumer, M., and Hohl, I. (1999). Vacuolar storage proteins and the putative vacuolar sorting receptor BP-80 exit the Golgi apparatus of developing pea cotyledons in different transport vesicles. Plant Cell 11, 1509–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R.A., Randazzo, P., Serafini, T., Weiss, O., Rulka, C., Clark, J., Amherdt, M., Roller, P., Orci, L., and Rothman, J.E. (1992). The amino terminus of ADP- ribosylation factor (ARF) is a critical determinant of ARF activities and is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein transport. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 13039–13046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, R.D., Donaldson, J.G., and Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (1992). Brefeldin A: Insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J. Cell Biol. 116, 1071–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuge, O., Hara-Kuge, S., Orci, L., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., Tanigawa, G., Wieland, F.T., and Rothman, J.E. (1993). Zeta-COP, a subunit of coatomer, is required for COP-coated vesicle assembly. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1727–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie, C., Paiement, J., Dominguez, M., Roy, L., Dahan, S., Gushue, J.N., and Bergeron, J.J.M. (1999). Roles for α2p24 and COPI in endoplasmic reticulum cargo exit site formation. J. Cell Biol. 146, 285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneur, F., Gaynor, E.C., Henneke, S., Demolliere, C., Duden, R., Emr, S.D., Riezman, H., and Cosson, P. (1994). Coatomer is essential for retrieval of dilysine-tagged proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 79, 1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou, W., Geuze, H.J., and Slot, J.W. (1996). Improving structural integrity of cryosections for immunogold labeling. Histochem. Cell Biol. 106, 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J., Cole, N.B., and Donaldson, J.G. (1998). Building a secretory apparatus: Role of ARF1/COPI in Golgi biogenesis and maintenance. Histochem. Cell Biol. 109, 449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, M., and Kreis, T.E. (1996). In vivo assembly of coatomer, the COP I coat precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30725–30730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, V., Serafini, T., Orci, L., Shepherd, J.C., and Rothman, J.E. (1989). Purification of a novel class of coated vesicles mediating biosynthetic protein transport through the Golgi stack. Cell 58, 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malsam, J., Gommel, D., Wieland, F.T., and Nickel, W. (1999). A role for ADP-ribosylation factor in the control of cargo uptake during COPI-coated vesicle biogenesis. FEBS Lett. 462, 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Menarguez, J.A., Geuze, H.J., Slot, J.W., and Klumpermann, J.A. (1999). Vesicular tubular clusters between the ER and Golgi mediate concentration of soluble secretory proteins by exclusion from COPI-coated vesicles. Cell 98, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira, P. (1990). Limited N-terminal sequence analysis. Methods Enzymol. 182, 602–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melançon, P., Glick, B.S., Malhotra, V., Weidman, P.J., Serafini, T., Gleason, M.L., Orci, L., and Rothman, J.E. (1987). Involvement of GTP-binding “G“ proteins in transport through the Golgi stack. Cell 51, 1053–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer, H.H., and Morré, D.J. (1994). Structure of the Golgi apparatus. Protoplasma 180, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Movafeghi, A., Happel, N., Pimpl, P., Tai, G.-H., and Robinson, D.G. (1999). Arabidopsis Sec21p and Sec23p homologs. Probable coat proteins of plant COP-coated vesicles. Plant Physiol. 119, 1437–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, W., Malsam, J., Gorgas, K., Ravazzola, M., Jenne, N., Helms, J.B., and Wieland, F.T. (1998). Uptake by COPI-coated vesicles of both anterograde and retrograde cargo is inhibited by GTPγS in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 111, 3081–3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprins, A., Duden, R., Kreis, T.E., Geuze, H.J., and Slot, J.W. (1993). β-COP localizes mainly to the cis-Golgi side in exocrine pancreas. J. Cell Biol. 121, 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci, L., Palmer, D.J., Amherdt, M., and Rothman, J.E. (1993). Coated vesicle assembly in the Golgi requires only coatomer and ARF proteins from the cytosol. Nature 364, 732–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci, L., Perrelet, A., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., Rothman, J.E., and Schekman, R. (1994). Coatomer-rich endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 8611–8615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci, L., Stamnes, M., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., Perrelet, A., Söllner, T.H., and Rothman, J.E. (1997). Bidirectional transport by distinct populations of COPI-coated vesicles. Cell 90, 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann, J., Orci, L., Tani, K., Amherdt, M., Ravazzola, M., Elazar, Z., and Rothman, J.E. (1993). Stepwise assembly of functionally active transport vesicles. Cell 75, 1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagny, S., Cabanes-Macheteau, M., Gillikin, J.W., Leborgne-Castel, N., Lerouge, P., Boston, R.S., Faye, L., and Gomord, V. (2000). Protein recycling from the Golgi apparatus to the endoplasmic reticulum in plants and its minor contribution to calreticulin retention. Plant Cell 12, 739–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D.J., Helms, J.B., Beckers, C.J., Orci, L., and Rothman, J.E. (1993). Binding of coatomer to Golgi membranes requires ADP-ribosylation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 12083–12089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperkok, R., Whitney, J.A., Gomez, M., and Kreis, T.E. (2000). COPI vesicles accumulating in the presence of a GTP restricted Arf1 mutant are depleted of anterograde and retrograde cargo. J. Cell Sci. 113, 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyroche, A., Paris, S., and Jackson, C.L. (1996). Nucleotide exchange on ARF mediated by yeast Gea1 protein. Nature 384, 479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyroche, A., Antonny, B., Robineau, S., Acker, J., Cherfils, J., and Jackson, C.L. (1999). Brefeldin A acts to stabilize an abortive ARF–GDP–Sec7 domain protein complex: Involvement of specific residues of the Sec7 domain. Mol. Cell 3, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regad, F., Bardet, C., Tremousaygue, D., Moisan, A., Lescure, B., and Axelos, M. (1993). cDNA cloning and expression of an Arabidopsis GTP-binding protein of the ARF family. FEBS Lett. 316, 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.G., and Hinz, G. (1997). Vacuolar biogenesis and protein transport to the plant vacuole: A comparison with the yeast vacuole and the mammalian lysosome. Protoplasma 197, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.G., and Hinz, G. (1999). Golgi-mediated transport of seed storage proteins. Seed Sci. Res. 9, 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.G., Ehlers, U., Herken, R., Herrmann, B., Mayer, F., and Schürmann, F.-W. (1987). Methods of Preparation for Electron Microscopy. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag). pp. 1–190.

- Robinson, D.G., Hinz, G., and Holstein, S.E.H. (1998). The molecular characterization of transport vesicles. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 49–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, J.E., and Wieland, F.T. (1996). Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science 272, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Sanderfoot, A., and Raikhel, N.V. (1999). The specificity of vesicle trafficking: Coat proteins and SNAREs. Plant Cell 11, 629–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satiat-Jeunemaitre, B., Cole, L., Bourett, T., Howard, R., and Hawes, C. (1995). Brefeldin A effects in plant and fungal cells: Something new about vesicle trafficking? J. Microsc. 181, 162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales, S.J., Pepperkok, R., and Kreis, T.E. (1997). Visualization of ER-to-Golgi transport in living cells reveals a sequential mode of action for COPII and COPI. Cell 90, 1137–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schekman, R., and Orci, L. (1996). Coat proteins and vesicle budding. Science 271, 1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa, G., Orci, L., Amherdt, M., Ravazzola, M., Helms, J.B., and Rothman, J.E. (1993). Hydrolysis of bound GTP by ARF protein triggers uncoating of Golgi-derived COP-coated vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1365–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyasu, K.T. (1986). Application of cryoultramicrotomy to immunocytochemistry. J. Microsc. 143, 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii, S., Banno, T., Watanabe, T., Ikehara, Y., Murakami, K., and Nakayama, K. (1995). Cytotoxicity of brefeldin A correlates with its inhibitory effect on membrane binding of COP coat proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11574–11580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, A., and Denecke, J. (1999). The endoplasmic reticulum—Gateway of the secretory pathway. Plant Cell 11, 615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, M.G., Serafini, T., and Rothman, J.E. (1991). “Coatomer”: A cytosolic protein complex containing subunits of non-clathrin-coated Golgi-transport vesicles. Nature 349, 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, D., and Flügge, U.I. (1984). A method for the quantitative recovery of proteins in dilute solutions in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal. Biochem. 138, 141–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]