Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease linked to misfolding of the ubiquitous enzyme Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD). In contrast to other protein-misfolding disorders with similar neuropathogenesis, ALS is not always associated with the in vivo deposition of protein aggregates. Thus, under the assumption that all protein-misfolding disorders share at primary level a similar disease mechanism, ALS constitutes an interesting disease model for identifying the yet-mysterious precursor states from which the cytotoxic pathway emerges. In this study, we have mapped out the conformational repertoire of the apoSOD monomer through analysis of its folding behavior. The results allow us to target the regions of the SOD structure that are most susceptible to unfolding locally under physiological conditions, leading to the exposure of structurally promiscuous interfaces that are normally hidden in the protein’s interior. The structure of this putative ALS precursor is strikingly similar to those implicated in amyloid disease.

Keywords: neurodegenerative disease, protein folding, transition state

An increasing number of severe neurodegenerative disorders have been linked to misfolding and subsequent aggregation of proteins (1). In some cases the protein aggregates deposit in the form of highly ordered amyloid fibrils (2), whereas in other cases they appear more granular or even amorphous (3). Even so, the main cause of neurotoxic function seems not to be the macroscopically deposited protein itself but rather a mysterious precursor species in the aggregation pathway (1, 4–6). In this perspective, it is notable that there are also disease cases where in vivo depositions of the disease-associated proteins are hard to find and sometimes are not even observable. Characteristic examples are found among the sporadic cases of Creuzfeldt–Jacob disease and amyotropic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (7). It is further apparent that the ALS-associated enzyme Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) has relatively low propensities to aggregate in vitro: SOD can be produced and analyzed by standard protocols despite being destabilized to the extent that it is half unfolded in physiological buffer at 25°C (8). For comparison there are few nondisease proteins that would resist aggregation under these conditions. The question then arises, do the disease cases with and without in vivo deposition of protein aggregates share at the primary level the same toxicity mechanism? We have previously observed that ALS-provoking SOD mutations produce a common shift of the folding equilibrium toward unfolded and partly folded monomers, implicating that the noxious side reaction emerges from the early folding events. The observation is in full agreement with a series of reports pointing at the immature apoSOD monomer as precursor for cytotoxicity (8–15). Accompanying the shift of the folding equilibrium, the ALS-associated SOD mutations indicate a quantitative relation between decreased protein stability, net charge, and disease progression (8). Taken together, these data suggest a disease mechanism that, at least in the familiar form of ALS, is linked to protein aggregation (16–19) or other associative processes triggered by ruptured structure and decreased repulsive charge, for example, overloading of the molecular chaperons (20) and adverse conglomeration with membrane lipids (21). In this study, we provide molecular detail on the ALS disease mechanisms by mapping out the folding behavior of the apoSOD monomer. The results, which are based on structural characterization of the critical folding nucleus by φ-value analysis (22), reveal not only how the apoSOD monomer gains and loses its native structure but implicates also from what point in the folding pathway the toxic cascade emerges. A key observation is that the apoSOD monomer has an intrinsic weakness in the form of labile edge strands protecting the hydrophobic center of the major β-sheet. Upon local unfolding of these protective strands the structure of SOD is analogous to that of the β2-microglobulin intermediate implicated in dialysis-related amyloidosis (23, 24) and the high-energy intermediate of the D67H lysozyme mutant triggering non-neuropathic systemic amyloidoses (25). It is thus apparent that ALS and fibril deposition conditions share a similar disease-provoking precursor species, despite fundamental differences in the amount, morphology, and cellular location of aggregated material depositing during the pathogenesis.

Results

The ApoSOD Monomer Folds Cooperatively According to a Two-State Transition.

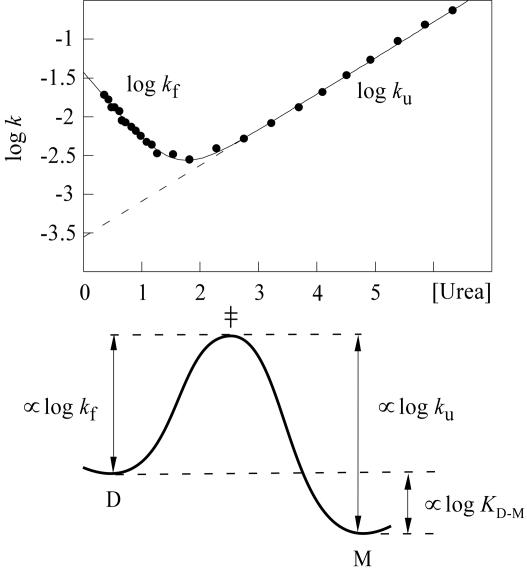

Folding of SOD in vitro is a stepwise reaction that starts with the cooperative formation of apo monomers (12, 26, 27). These marginally stable apo species have also emerged as potential precursors in the ALS mechanism (8–15). As observed for many other small single-domain proteins (28, 29), the apoSOD monomer displays a two-state transition with a characteristic v-shaped chevron plot following Eqs. 1 and 2 (Fig. 1). The absence of populated intermediates indicates that the folding reaction proceeds mainly by high-energy states forming a free-energy barrier between the denatured ensemble (D) and the final monomeric structure (M). In analogy with classical Arrhenius theory, the ensemble of conformations at the top of this barrier is referred to as the transition state or the critical folding nucleus (‡) (30). The position of ‡ relative to D and M on the progress coordinate can either be estimated in terms of exposed surface area from the slopes of the chevron limbs [β‡ = mf/(mf − mu), see Eq. 2] (30) or in terms of contact formation from the slope of a Brönstedt plot, B‡ = −∂Δ log kf/∂Δ log KD-M (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) (31). For the pseudo WT monomer used in this study (i.e., the mutant C6A/C111A/F50E/G51E), the values are β‡ = 0.67 and B‡ = 0.28, respectively, indicating that the barrier top is located approximately halfway through the folding reaction. The folding behavior of this construct is fully analogous to that of the WT monomer but shows no partitioning from erroneous disulphide cross-linking.

Fig. 1.

The chevron plot of the pseudo WT monomer of apoSOD (Upper) illustrating a two-state transition between the denatured (D) and folded monomer (M) proceeding over a single transition state (‡) (Lower).

The φ-Value Analysis.

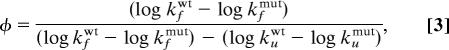

Compared with other proteins associated with misfolding disease the apoSOD monomer offers a considerable advantage: the simplistic two-state behavior allows detailed analysis of its folding reaction by protein engineering. The approach is generally referred to as φ-value analysis (22) and uses truncation of individual side-chain moieties to map out the subset of native-like interactions formed in the transition-state ensemble (‡) at the top of the folding free-energy barrier (Fig. 1). In essence, mutations that decrease the folding rate constant are assumed to target side-chain contacts that are engaged in the transition-state structure and the quality of the targeted contacts is given by the φ value (Eq. 3). A φ value of 1 indicates that the structural environment of the mutated side chain is fully native-like, whereas a φ value of 0 indicates that it is disordered. The mutations used as site-specific probes in this study have been chosen to cover in a comprehensive way the network of tertiary contacts linking the secondary-structure elements of the apoSOD monomer (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To reconstruct as closely as possible the unfolding events taking place under physiological conditions, we have chosen to analyze SOD molecules with the C57–C146 disulphide linkage intact: the most likely starting material for unfolding of the apo monomer in vivo. The successful expression and easy handling of several mutants that are only partly folded in physiological buffer suggest interestingly that SOD has a sequence composition that has been evolved to operate under low-stability conditions. For most other globular proteins such radical destabilization would lead to severe losses because of aggregation. The association between SOD and neurodegenerative disease, however, indicates that this adaptation to resist unwanted side reactions is at some level still insufficient.

The Transition-State Structure of the ApoSOD Monomer.

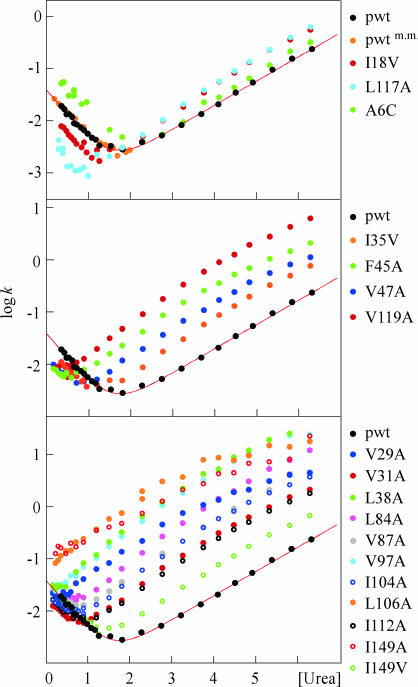

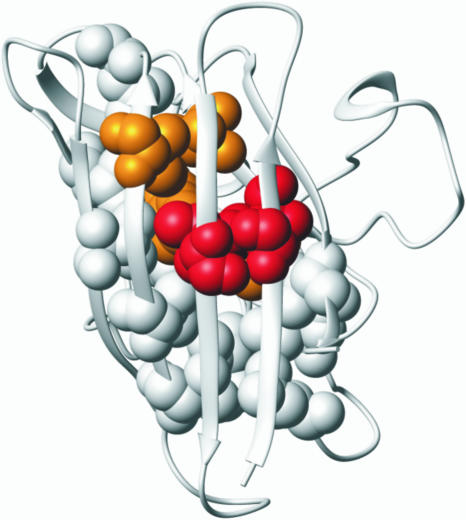

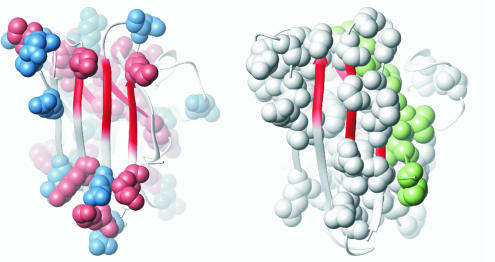

The highest φ values of the apoSOD monomer (φ > 0.6) are observed for the mutations A6C, I18V, and L117A (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The side chains of these residues form a tightly packed triad linking strands β1, β2, and β7 through the center of the hydrophobic core (Fig. 3). Flanking the high-φ triad is a layer of residues with φ values between 0.6 and 0.3, revealed by the mutations I35V in β3, F45A and V47A in β4, and V119A in β7. The mutations with high and intermediate φ values thus define a contiguous cluster of side chains in the shape of a five-stranded motif that embraces the hydrophobic core in a sandwich-like fashion: β1–β2–β3 folds up against β4–β7 (Fig. 3). These are the interactions that define the key topology of the folding nucleus: the set of tertiary contacts needed to overcome the chain entropy to turn the folding free energy profile downhill. A notable feature of the apoSOD nucleus is that the entropic cost of forming the different contacts is markedly different. Condensation of strands β1, β2, β3, and β4 is relatively easy because these are close in the primary sequence, whereas the integration of β7 is more unfavorable because it is distanced by a long loop. There are two immediate implications of this somewhat unusual sequence arrangement. First, the part of the folding nucleus that is close in sequence could be flickeringly present in the denatured ensemble, providing a potential seed for domain-swap reactions (32), i.e., the protein becomes prone to integrate a matching element from a neighboring molecule. Such domain-swap reactions have been implicated as a key event in fibrillation of globular proteins (33, 34) and have been extensively studied for the serpin family where the exchange of individual β-strands also has a regulatory function (35). Second, the considerable sequence distance between β7 and the other nucleating strands provides an explanation for why the folding of the SOD monomer is slower than for most other Ig domains (cf. ref. 36). Capturing β7 is simply difficult for statistical reasons. The integration of strand β7 also seems to be the decisive event that leads to barrier passage and productive folding. To complete the picture, the positions with low φ values (φ < 0.3) are observed in the peripheral strands β5–β6 and β8 that cap either side of the central folding nucleus and at the beginning of β3 (Fig. 3). At the extreme, is the mutation I149V in β8 with a φ value of ≈0, closely followed by L84A and V87A in β5 with φ values near 0.1 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Low φ values for the β8 region and the associated catalytic loop IV have also been inferred independently from the folding behavior of completely cysteine-depleted SOD (12). The results suggest that the envelop of residues that normally protects the hydrophobic interior of the SOD monomer is largely unfolded in the transition-state ensemble. Although the precise nature of this outer boundary of the transition-state structure is intrinsically difficult to pin down (37, 38), it can be safely concluded that the side chains with low φ values consolidate mainly on the downhill side of the folding barrier. Vice versa, these side chains define the regions of the SOD structure that ruptures early in the unfolding process, i.e., what is missing at the top has been lost on the way up.

Fig. 2.

Chevron plots of the mutants in Table 1, grouped according to high (Top), medium (Middle), and low (Bottom) φ values. m.m. denotes data from manual mixing.

Table 1.

Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters

| Mutant | log kfH2O | log kuH2O | log ku3M | mu | Midpoint, M | mD-M | ΔGD-M,H2O kcal·mol−1 | ΔΔG, (kcal·mol−1) | φ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pwt | −1.42 | −3.53 | −2.17 | 0.45 | 1.54 | 1.37 | 2.87 | ||

| A6C | −0.90 | −3.67 | −2.14 | 0.51 | 1.94 | 1.43 | 3.77 | −0.90 | 1.06 |

| I18V* | −1.82 | −3.65 | −1.90 | 0.58 | 1.22 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 0.37 | 0.60 |

| V29A | −1.86 | −1.90 | −0.26 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 1.47 | 0.06 | 2.81 | 0.19 |

| V31A | −1.80 | −2.89 | −1.10 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 1.52 | 1.48 | 1.39 | 0.26 |

| I35V* | −1.68 | −3.31 | −1.67 | 0.55 | 1.11 | 1.47 | 2.21 | 0.66 | 0.35 |

| L38A† | −1.73 | −1.67 | 0.22 | 0.63 | −0.04 | 1.55 | −0.09 | 2.95 | 0.12 |

| F45A | −2.13 | −2.72 | −0.96 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 1.51 | 0.80 | 2.07 | 0.37 |

| V47A | −1.94 | −2.99 | −1.36 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 1.46 | 1.42 | 1.45 | 0.39 |

| F64A | −1.39 | −3.64 | −2.22 | 0.47 | 1.62 | 1.40 | 3.07 | −0.20 | |

| V81A | −1.42 | −3.52 | −2.09 | 0.48 | 1.51 | 1.40 | 2.86 | 0.01 | |

| L84A | −1.65 | −2.40 | −0.46 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 1.56 | 1.02 | 1.85 | 0.12 |

| V87A | −1.59 | −2.52 | −0.81 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 1.49 | 1.26 | 1.61 | 0.11 |

| V97A† | −1.78 | −1.75 | 0.16 | 0.64 | −0.02 | 1.56 | −0.03 | 2.90 | 0.13 |

| I104A | −1.71 | −2.70 | −0.82 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 1.55 | 1.34 | 1.53 | 0.18 |

| L106A† | −1.77 | −1.15 | 0.55 | 0.57 | −0.41 | 1.49 | −0.84 | 3.71 | 0.11 |

| A111C | −1.45 | −3.86 | −2.35 | 0.51 | 1.70 | 1.43 | 3.29 | −0.42 | |

| I112A | −1.69 | −2.88 | −1.20 | 0.56 | 0.80 | 1.48 | 1.61 | 1.25 | 0.22 |

| L117A | −2.64 | −3.45 | −1.85 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 1.45 | 1.09 | 1.78 | 0.80 |

| V119A | −2.27 | −2.51 | −0.62 | 0.63 | 0.15 | 1.55 | 0.32 | 2.55 | 0.35 |

| L144A | −1.54 | −3.74 | −2.33 | 0.47 | 1.59 | 1.39 | 3.00 | −0.13 | |

| I149A | −1.85 | −0.98 | 0.15 | 0.38 | −0.67 | 1.30 | −1.18 | 4.05 | 0.16 |

| I149V | −1.43 | −3.34 | −1.72 | 0.54 | 1.31 | 1.46 | 2.60 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

*The alternative substitutions I18A and I35A could not be expressed in sufficient amounts.

†kf was calculated from ku and the unfolding amplitudes as described in Experimental Procedures.

Fig. 3.

Structural distribution of side-chain mutations with φ >0.6 (red), 0.3 < φ <0.6 (orange), and φ <0.3 (white).

Discussion

Extra Strand and Long Catalytic Loops Yield Characteristic Folding Behavior of the SOD Monomer.

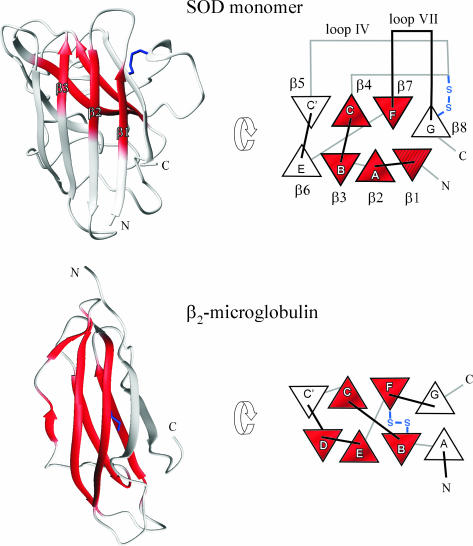

Compared with other proteins in the Ig-like β-sandwich family, the SOD structure shows two features with direct implications for its folding behavior. First, SOD has an additional strand at the N terminus, β1, which interacts directly with the C-terminal strand β8, creating a half-barrel core rather than a typical two-sheet sandwich (39). Second, SOD has two long loops (IV and VII) that extend from either end of the barrel to pinch the active-site metals (39). As a result of these features, the transition-state structure of the apoSOD monomer differs from those of more typical Ig-like proteins (Fig. 4). Most notably, the center of the folding nucleus is shifted toward the C-terminal side of the structure and has an altered sequence separation between the nucleating contacts; the apoSOD nucleus encompasses the consecutive strands β1–β4, plus the distant β7, whereas the Ig-like proteins CD2d1 (40) and Tnfn3 (41) show a common nucleation motif based on two interdigitating hair pins that are symmetrically dispersed in the primary sequence. An explanation for this shifted nucleation pattern is that the additional β1 strand in SOD increases the volume of the hydrophobic core and thereby moves apart the hairpins of the CD2d1 and TNfn3 nuclei. Despite these marked differences between the SOD and CD2d1/Tnfn3 nuclei, it is evident that the side chains with the highest φ values remain within a single packing layer (42) of the proteins’ β-pleated cores (41). The shared nucleation behavior supports the notion that early establishment of correct β register is a key event in the folding of Ig-like proteins (41).

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of the folding nucleus of the apoSOD monomer (red) and the regions that rupture most easily in the unfolding process, i.e., the protective caps (white). Local unfolding of the protective caps through thermal motions of the folded monomer would thus produce a species that closely matches the ordered (red) and disordered (white) regions of the β2-microglobulin intermediate implicated as precursor in dialysis-related amyloidosis. This β2-microglobulin intermediate retains stable structure in five of the seven β-strands (23).

Local Unfolding of Protective Caps Exposes Sticky Edge Strands: Implications for the ALS Mechanism.

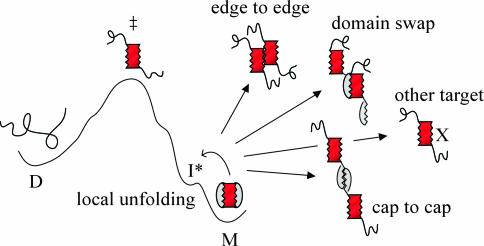

We have previously demonstrated that certain charged side chains at the exposed edge strand of the ribosomal protein S6 are conserved as aggregation gatekeepers (43). Mutational truncation of these gatekeepers has no effect on folding or stability but triggers aggregation of the coil and tetramerization of the native state (43) and amyloid formation on longer time scales (44). Subsequent surveys have shown that such protection of otherwise aggregation-prone edge strands is not unique for S6 but occurs as a general design principle for β proteins (45–47). Consistently, aggregation gatekeepers are also found at the β-sheet edges of the SOD structure (Fig. 5). Strands β5 and β6 at the open-ended side of the half-barrel contain several strategically placed charges and are also partially concealed by loops IV and VII (39). The other critical flank of the protein, involving the interface between the N- and C-terminal strands β1 and β8, is sealed by continuous hydrogen bonding. In terms of edge protection, the folded SOD monomer appears to be a fairly typical protein. When looking at a more global level, however, the charges display an intriguing pattern: strands β1–β3 form a contiguous charge-free segment of mainly hydrophobic side chains at the center of the sheet (Fig. 5). There are two traits of this conspicuous charge distribution that are of particular interest for the ALS mechanism. First, the charge-free segment is capped at either end by the charged strands β6 and β8, and without this edge protection the naked segment constitutes a potential seed for aggregation or other side reactions driven by burial of hydrophobic surface area. Second, the charge pattern coincides with the distribution of high and low φ values: the charge-free segment is part of the folding nucleus, whereas the protective strands β6 and β8 are largely unfolded in the transition-state ensemble. Thus, it is implicated that the protective strands will rupture early in the unfolding process, exposing the edges of the charge-free segment in a series of a high-energy states on the native side of the folding barrier (Fig. 6). If these high-energy states are within close energetic reach of the native structure they are also sampled regularly through thermal fluctuations. Such sampling would be seen as fraying, excessive breathing, or local unfolding of the structure with low φ values (48, 49). Local fluctuations in other directions of the conformations space are also possible but are likely to be more restricted because they do not lead to productive unfolding (50). Minimizing the occupancy of partially unfolded states and residual structure in the denatured ensemble has recently emerged as an important evolutionary determinant that underlies the high folding cooperativity of natural proteins (25, 48). In support of this view, it has been demonstrated that the amyloidogenic properties of β2-microglobulin are linked to local unfolding of the N- and C-terminal strands A and G, producing a precursor state that closely resembles that of the SOD monomer (23) (Fig. 4). Moreover, the in vitro aggregation of a disease-associated mutation of human lysozyme coincides with increased sampling of a partially unfolded state exposing contiguous stretches of sheet residues, again in perfect analogy with the early unfolding of the protective caps of SOD (25, 51). In this perspective it is notable that the β5–β6 cap of the SOD monomer is separated from the sheet by sequence loops that are substantially longer than for other Ig-like proteins (Fig. 4), leading to slower diffusive open and close movements and ruptured states that are relatively long-lived. The susceptibility of SOD to trigger conformational disease could then stem from a built-in compromise between structural integrity and the functional requirement of maintaining long catalytic loops.

Fig. 5.

Positively (red) and negatively (blue) charged residues form a layer of aggregation gatekeepers around the folding nucleus of SOD (red). Upon local unfolding of the protective caps the hydrophobic center of the β-sheet are exposed naked to the solvent, presenting a putative seed for noxious side reactions. The ALS-associated SOD mutations (white) are mainly within or at the interface to the protective caps, and in several ALS-provoking truncation variants the cap protecting the hydrophobic N-terminal strand β1 is completely missing (green).

Fig. 6.

Schematic picture of the SOD unfolding process illustrating the formation of a high-energy intermediate (I*) in which the protective caps are disordered, leading to the exposure of a “sticky” element defined by the folding nucleus (red). As a result of this exposure, it is easy to envisage a series of different side reactions leading to homo aggregation or erroneous interference with other biological macromolecules (X).

ALS-Associated Mutations Mainly Affect Late Folding Events: Perturbation of the Protective Caps.

Sequence analysis of ALS-associated SOD truncations shows that the disease-provoking features of the protein are unlikely at the C-terminal end of the polypeptide chain. Truncated proteins that lack the major part of loop VII and β8 are as disease-competent as the most severe missense mutations (52). Notably, these truncations represent direct mimics of high-energy intermediates with disordered C-terminal cap, exposing the N-terminal edge of the charge-free sheet segment (Fig. 5). A disease model based on local unfolding of the edge strands is further supported by the structural distribution and folding behavior of ALS-provoking point mutations. The majority of the 103 ALS mutations reported to date (52) are located outside of the folding nucleus or at the interface between the folding nucleus and the protective caps (Fig. 5). Even so, there are also clear exceptions, e.g., F20C in β2 producing a large cavity in the center of the hydrophobic core. However, this scattered localization of the ALS mutations is not surprising because (i) the energetic effect of residue substitutions is not easily predicted from crystallographic data alone (30) and (ii) the disease progression has been shown to depend also on nonenergetic factors like the protein’s net charge (8). Consistently, a clearer picture emerges upon direct comparison with the folding behavior of the disease-provoking proteins: the 15 ALS mutations surveyed in ref. 8 perturb predominantly the structure forming after the monomer transition state. In other words, the ALS-associated mutations destabilize selectively the protective caps or otherwise increase the occupancy of partly unfolded monomers through destabilization of species downstream in the SOD maturation process. On this basis we conclude that the apoSOD monomer caused by compromised folding cooperativity is intrinsically susceptible to undergoing promiscuous side reactions and that this susceptibility is augmented by the ALS-associated SOD mutations. Sporadic ALS would thus result from misfolding or aggregation of WT SOD, possibly coupled to sporadic defects in the cellular maintenance systems that normally compensate for the nonideal properties of the SOD molecule. Familial ALS would arise from the increased stickiness of SOD itself, which eventually exhausts even a perfectly healthy cellular maintenance system. Such increased stickiness can result either from mutations that increase the exposure of disease-seeding material (8, 25) or mutations that decrease the protein’s repulsive charge (8, 53). The former group includes mutations that both destabilize the protective caps and rise the total level of monomeric SOD material by weakening the dimer interface (8, 10) and preventing proper ligation of the catalytic metals (39).

Implication of a Mechanistic Link Between ALS and Fibril Deposition Disease.

Taken together, the present data suggest that the actual seed for cytotoxic function in ALS is contained within the charge-free sheet segment involving strands β1, β2, and β3. This putative precursor species is both structurally and mechanistically closely related to the monomeric intermediates implicated as sticky precursors in fibril deposition disease. The resemblance is particularly striking in the case of dialysis-related amyloidosis where the key features of the β2-microglobulin precursor as observed by NMR are virtually identical to the cap-depleted SOD monomer (23, 24). Moreover, the local unfolding reaction of the SOD monomer shows close resemblance with that of the amyloidogenic lysozyme mutant D67H (25). An equally striking difference between ALS and these amyloid diseases is, nevertheless, the amount of deposited protein. In ALS, SOD aggregates are generally difficult to detect and in cases where they do occur they are scattered intracellularly as small granular inclusions (54). In contrast, the disease progression of dialysis-related and systemic amyloidosis is accompanied by massive in vivo deposition of fibrillar structures (2). Following the findings that fibrillation and “amorphous” aggregation are controlled by different sequence determinants (55), it cannot a priori be assumed that the prefibrillar assemblies implicated as principal stepping stones in amyloid disease are also present in protein disease lacking amyloid deposits. Different aggregate morphologies can form by different pathways. Even so, it is apparent that the noxious side reactions in ALS and fibril deposition disease emerge from analogous points in the protein folding process and, thus, start off along similar misfolding pathways. Whether the cytotoxic function that eventually arises along these misfolding pathways is on route to macroscopic aggregation or constitutes a parallel mechanism remains to be established.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Preparation.

The mutants were constructed on a background of C6A/C111A and the dimer-splitting substitutions F50E/G51E, coexpressed with yeast copper chaperone and purified as described (56). F50E/G51E is needed to resolve the monomer unfolding process as the WT unfolding is rate-limited by dimer splitting, and C6A/C111A reduces the extent of erroneous cross-linking. The folding behavior of this construct is indistinguishable from that of the WT monomer (12). Apo protein was prepared as described (12), and the standard buffer was 10 mM Mes (Sigma) at pH 6.3 with 10 mM EDTA to maintain the proteins metal-free in all steps of the analysis. For the mutations L8A, I18A, F20A, and I35A, the expression levels were too low for preparation. For positions 18 and 35 protein was obtained by the alternative substitution to V.

Kinetic Measurements.

Stopped-flow measurements and curve fitting were performed on a SX-17MV stopped-flow spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, U.K.). The excitation was at 280 nm, the emission was collected >305 nm, and the final protein concentration was 2 μM. For the slow-folding mutant L117A, control experiments were conducted by manual mixing. All measurements were done at 25°C, using urea as denaturant (ultra PURE; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH).

Data Analysis.

The SOD monomer was assumed to display minimal two-state behavior,

where ΔGD-M is the protein stability, KD-M = [D]/[M], and ku and kf are the unfolding and refolding rate constants, respectively. The folding and unfolding m values were derived from the linear regime at the bottom of the chevron plots by using the standard equation

|

where kfH2O and kuH2O are the rate constants at [urea] = 0 M, and mf and mu are the slopes of the refolding and unfolding limbs, respectively. In all fits, mf was locked to the WT value to reduce extrapolation errors for mutants with low midpoint. The φ values probing the extent of contact formation in the protein folding transition state (30) were calculated from chevron data according to ref. 57

|

where kf and ku were measured at 0 and 3 M urea, respectively. The φ value for position 6 was calculated from the mutation A6C reintroducing the WT side chain. Calculations of φ by this alternative method are fully analogous to those using side-chain truncations but reverse the effects on the refolding and unfolding rate constants (Fig. 2). To assure accurate results for low-stability mutants with poorly defined kf, i.e., V29A, L38A, V97A, L106A, and I149A, we estimated in these cases kf from unfolding amplitudes and ku alone following Eq. 1. For example, the unfolding amplitude of V97A is 51% of that for the pseudo WT protein, suggesting that the starting material of V97A at 0 M urea is only 51% folded, i.e., KD-M = [D]/[M] = ku/kf = 0.96. With an extrapolated value of ku = 0.018 s−1 this yields φ = 0.13 according to Eq. 3 (Table 1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Marklund and Magnus Lindberg for stimulating discussions and the Bertil Hållsten Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, and the Göran Gustafssons Foundation for financial support.

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- SOD

superoxide dismutase.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Dobson C. M. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westermark P., Benson M. D., Buxbaum J. N., Cohen A. S., Frangione B., Ikeda S., Masters C. L., Merlini G., Saraiva M. J., Sipe J. D. Amyloid. 2005;12:1–4. doi: 10.1080/13506120500032196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefani M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1739:5–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silveira J. R., Raymond G. J., Hughson A. G., Race R. E., Sim V. L., Hayes S. F., Caughey B. Nature. 2005;437:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature03989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman M. Y., Goldberg A. L. Neuron. 2001;29:15–32. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor J. P., Hardy J., Fischbeck K. H. Science. 2002;296:1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson D. Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders. Basel: ISN Neuropath Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg M. J., Bystrom R., Boknas N., Andersen P. M., Oliveberg M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9754–9759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501957102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakhit R., Crow J. P., Lepock J. R., Kondejewski L. H., Cashman N. R., Chakrabartty A. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15499–15504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hough M. A., Grossmann J. G., Antonyuk S. V., Strange R. W., Doucette P. A., Rodriguez J. A., Whitson L. J., Hart P. J., Hayward L. J., Valentine J. S., Hasnain S. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5976–5981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305143101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch S. M., Boswell S. A., Colon W. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16525–16531. doi: 10.1021/bi048831v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindberg M. J., Normark J., Holmgren A., Oliveberg M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15893–15898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403979101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa Y., O’Halloran T. V. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:17266–17274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa Y., Torres A. S., O’Halloran T. V. EMBO J. 2004;23:2872–2881. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnesano F., Banci L., Bertini I., Martinelli M., Furukawa Y., O’Halloran T. V. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47998–48003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruijn L. I., Houseweart M. K., Kato S., Anderson K. L., Anderson S. D., Ohama E., Reaume A. G., Scott R. W., Cleveland D. W. Science. 1998;281:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston J. A., Dalton M. J., Gurney M. E., Kopito R. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12571–12576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220417997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stathopulos P. B., Rumfeldt J. A., Scholz G. A., Irani R. A., Frey H. E., Hallewell R. A., Lepock J. R., Meiering E. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7021–7026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung J., Yang H., de Beus M. D., Ryu C. Y., Cho K., Colon W. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;312:873–876. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okado-Matsumoto A., Fridovich I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9010–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132260399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sparr E., Engel M. F., Sakharov D. V., Sprong M., Jacobs J., de Kruijff B., Hoppener J. W., Killian J. A. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matouschek A., Kellis J. T., Jr., Serrano L., Fersht A. R. Nature. 1989;340:122–126. doi: 10.1038/340122a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McParland V. J., Kalverda A. P., Homans S. W., Radford S. E. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nsb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platt G. W., McParland V. J., Kalverda A. P., Homans S. W., Radford S. E. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:279–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canet D., Last A. M., Tito P., Sunde M., Spencer A., Archer D. B., Redfield C., Robinson C. V., Dobson C. M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nsb768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mei G., Rosato N., Silva N., Jr., Rusch R., Gratton E., Savini I., Finazzi-Agro A. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7224–7230. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stroppolo M. E., Malvezzi-Campeggi F., Mei G., Rosato N., Desideri A. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;377:215–218. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson S. E. Folding Des. 1998;3:R81–R91. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveberg M. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001 doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fersht A. R. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. New York: Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedberg L., Oliveberg M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308497101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rousseau F., Schymkowitz J. W., Itzhaki L. S. Structure (London) 2003;11:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y., Gotte G., Libonati M., Eisenberg D. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:211–214. doi: 10.1038/84941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanova M. I., Sawaya M. R., Gingery M., Attinger A., Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10584–10589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilczynska M., Lobov S., Ohlsson P. I., Ny T. EMBO J. 2003;22:1753–1761. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamill S. J., Cota E., Chothia C., Clarke J. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:641–649. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onuchic J. N., Wolynes P. G. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubner I. A., Oliveberg M., Shakhnovich E. I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8354–8359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401672101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strange R. W., Antonyuk S., Hough M. A., Doucette P. A., Rodriguez J. A., Hart P. J., Hayward L. J., Valentine J. S., Hasnain S. S. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:877–891. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorch M., Mason J. M., Clarke A. R., Parker M. J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1377–1385. doi: 10.1021/bi9817820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamill S. J., Steward A., Clarke J. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;297:165–178. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lesk A. M., Branden C. I., Chothia C. Proteins. 1989;5:139–148. doi: 10.1002/prot.340050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otzen D. E., Kristensen O., Oliveberg M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9907–9912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160086297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otzen D. E., Oliveberg M. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1417–1421. doi: 10.1110/ps.03538904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ventura S., Zurdo J., Narayanan S., Parreno M., Mangues R., Reif B., Chiti F., Giannoni E., Dobson C. M., Aviles F. X., Serrano L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7258–7263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308249101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thirumalai D., Klimov D. K., Dima R. I. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:146–159. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindberg M., Tangrot J., Oliveberg M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nsb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Englander S. W. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke J., Itzhaki L. S. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8:112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dumoulin M., Canet D., Last A. M., Pardon E., Archer D. B., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A., Robinson C. V., Redfield C., Dobson C. M. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:773–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen P. M., Sims K. B., Xin W. W., Kiely R., O’Neill G., Ravits J., Pioro E., Harati Y., Brower R. D., Levine J. S., et al. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003;4:62–73. doi: 10.1080/14660820310011700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiti F., Stefani M., Taddei N., Ramponi G., Dobson C. M. Nature. 2003;424:805–808. doi: 10.1038/nature01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kato S., Nakashima K., Horiuchi S., Nagai R., Cleveland D. W., Liu J., Hirano A., Takikawa M., Kato M., Nakano I., et al. Neuropathology. 2001;21:67–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2001.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rousseau F., Schymkowitz J., Serrano L. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindberg M. J., Tibell L., Oliveberg M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16607–16612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262527099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otzen D. E., Oliveberg M. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:613–627. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.