Abstract

Plant UDP-Glc:phenylpropanoid glucosyltransferases (UGTs) catalyze the transfer of Glc from UDP-Glc to numerous substrates and regulate the activity of compounds that play important roles in plant defense against pathogens. We previously characterized two tobacco salicylic acid– and pathogen-inducible UGTs (TOGTs) that act very efficiently on the hydroxycoumarin scopoletin and on hydroxycinnamic acids. To identify the physiological roles of these UGTs in plant defense, we generated TOGT-depleted tobacco plants by antisense expression. After inoculation with Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), TOGT-inhibited plants exhibited a significant decrease in the glucoside form of scopoletin (scopolin) and a decrease in scopoletin UGT activity. Unexpectedly, free scopoletin levels also were reduced in TOGT antisense lines. Scopolin and scopoletin reduction in TOGT-depleted lines resulted in a strong decrease of the blue fluorescence in cells surrounding TMV lesions and was associated with weakened resistance to infection with TMV. Consistent with the proposed role of scopoletin as a reactive oxygen intermediate (ROI) scavenger, TMV also triggered a more sustained ROI accumulation in TOGT-downregulated lines. Our results demonstrate the involvement of TOGT in scopoletin glucosylation in planta and provide evidence of the crucial role of a UGT in plant defense responses. We propose that TOGT-mediated glucosylation is required for scopoletin accumulation in cells surrounding TMV lesions, where this compound could both exert a direct antiviral effect and participate in ROI buffering.

INTRODUCTION

Plants are characterized by their ability to synthesize numerous different secondary metabolites, among them phenylpropanoids, which are derived from Phe and fulfill a wide range of important biological functions (Dixon and Paiva, 1995). It is well established that phenylpropanoid metabolism is one of the major metabolic pathways stimulated during the hypersensitive response (HR), a very efficient mechanism of induced disease resistance in plants. The HR is characterized by localized cell and tissue death at the site of infection and is associated with the induction of intense metabolic alterations, resulting in confinement of the pathogen (Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996; Fritig et al., 1998). One of the earliest responses underlying HR cell death in plants is the increase in the production of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs), giving rise to the so-called oxidative burst (Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996).

Among the ROIs, O2.− and H2O2 may be key mediators of cell death characterizing the HR (Dangl et al., 1996). On the other hand, H2O2 from the oxidative burst also could act as a diffusible signal for the induction of protectant genes in cells adjacent to HR lesions, thereby limiting oxidant-mediated cell death (Lamb and Dixon, 1997). The cells surrounding the HR lesion actually are stimulated strongly without being destined to die, and they produce a large set of defense responses that contribute to the efficient restriction of pathogen spread (Dorey et al., 1997; Fritig et al., 1998). In tobacco treated with an HR-inducing elicitor, this narrow zone of living cells expressing sustained defense responses is characterized by blue fluorescence under UV light, which is attributable to the accumulation of phenylpropanoids (Dorey et al., 1997).

Many of the pathogen-induced phenylpropanoids (e.g., coumarins and isoflavonoids) are considered phytoalexins because they exhibit antimicrobial properties in vitro and accumulate to antimicrobial concentrations in plant tissues upon infection (Dixon and Paiva, 1995; Kuc, 1995; He and Dixon, 2000). Besides their antimicrobial properties, phenylpropanoids such as the ubiquitous chlorogenic acid (3-caffeoylquinic acid) display antioxidant properties in vitro (Rice-Evans et al., 1997), and hydroxycoumarins such as scopoletin (6-methoxy-7-hydroxycoumarin) have been proposed to act in planta as scavengers of ROI excess produced after triggering of the HR (Chong et al., 1999). Moreover, salicylic acid (SA) originating from the phenylpropanoid pathway (Coquoz et al., 1998; Chong et al., 2001) plays key roles in the signaling network leading to the establishment of both local and systemic resistance (Gaffney et al., 1993; Delaney et al., 1994).

Phenylpropanoids rarely accumulate in their free form in plant cells but often are conjugated to sugars, most often Glc, through the action of UDP-Glc:glucosyltransferases (UGTs) (Vogt and Jones, 2000). Many properties of the aglycones are regulated by glucosylation. Secondary metabolite glucosides generally exhibit reduced chemical reactivity and enhanced water solubility and can act as storage and transport forms (Li et al., 2001). Glucosylation thus plays a general role in the accumulation of phenylpropanoids that would be toxic in their free form; in addition, phenylpropanoid glucosides also are believed to be of importance in plant defense. The 4-O-β-d-glucosides of monolignols are considered to serve as transport forms of lignin monomers into the cell wall, leading to enhanced lignification after pathogen attack (Whetten et al., 1998). Glc esters of hydroxycinnamic acids also are thought to act as intermediates for trans-esterification and impregnation of cinnamate derivatives into the cell wall (Hahlbrock and Scheel, 1989). Moreover, conjugation reactions catalyzed by UGTs may be critical in regulating the levels of signaling compounds such as SA by converting active molecules to inactive conjugated forms (Hennig et al., 1993).

Despite the remarkable capacity of plants to glucosylate a wide range of different chemical structures, UGTs were largely unknown until recently. Analysis of the completed Arabidopsis genome indicates the existence of >100 genes encoding putative glucosyltransferases, but the functions of most of them have not been elucidated (Li et al., 2001). However, within the last 2 years, cloning and substrate specificity analysis of several plant phenylpropanoid UGTs acting on anthocyanidins, flavonoids, and hydroxycinnamic acids have shed new light on the functions of some members of the UGT superfamily (Ford et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 1999; Hirotani et al., 2000; Vogt and Jones, 2000; Lim et al., 2001).

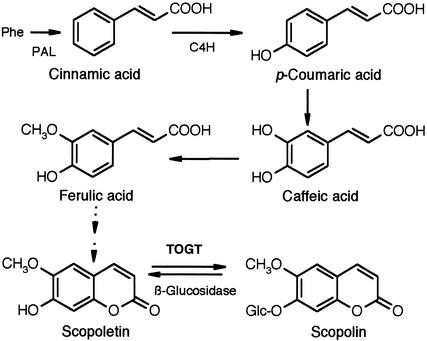

Among the UGTs that could be involved in plant defense, a SA- and pathogen-inducible UGT acting in vitro on the signaling molecules SA, benzoic acid, and cinnamic acid has been isolated in tobacco (Lee and Raskin, 1999). Recently, we showed that two tobacco genes (Togt1 and Togt2), which are induced early by SA and during an HR (Horvath and Chua, 1996; Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), encode UGTs that act efficiently on hydroxycoumarins, especially scopoletin (Figure 1), and on hydroxycinnamic acids (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). These genes are homologous with a glucosyltransferase gene from tomato (Twi1) that responds rapidly to wound- and pathogen-related signals (O'Donnell et al., 1998).

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic Pathway to Scopoletin and Scopolin.

Scopoletin synthesis involves the first catalytic steps of the phenylpropanoid pathway, leading to p-coumaric acid. Ferulic acid has been demonstrated as a scopoletin precursor in cultured tobacco cells (Fritig et al., 1970); however, specific enzymes of scopoletin biosynthesis are not known. In vitro, scopoletin is glucosylated very efficiently by TOGT (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase.

One way of identifying unambiguously the role of UGTs in planta is to manipulate their expression. Until now, the isolation of the maize bronze-1 transposon-tagging mutants was the only example of the unequivocal identification of the function of a flavonol-3-O-glucosyltransferase (Fedoroff et al., 1984). The modulation of a specific UGT in vivo and the study of its effect on phenylpropanoid metabolism and defense mechanisms have not been performed. Using a loss-of-function approach based on tobacco salicylic acid– and pathogen-inducible UGT (TOGT) antisense inhibition in transgenic plants, we show clearly the function of TOGT in hydroxycoumarin glucosylation and the crucial role of this UGT in virus resistance. Our work further assigns new roles for scopoletin in plant defense, as both an antiviral compound and an antioxidant molecule involved in the regulation of ROI accumulation.

RESULTS

Generation of Transgenic Tobacco Plants with Reduced TOGT Levels

We previously showed that TOGT is encoded by two genes, Togt1 and Togt2, in tobacco (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). Both genes are expressed at similar levels upon elicitation of defense responses or treatment with SA, and they share 95% nucleotide identity in the coding region. To downregulate the expression of both Togt genes, the complete coding sequence of Togt1 was introduced in the antisense orientation downstream from the constitutive 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus into tobacco. Togt antisense expression in plants had no effect on normal growth and development.

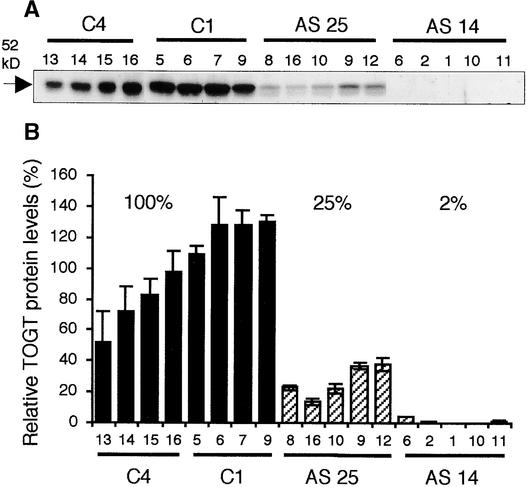

Because Togt gene expression is known to be induced rapidly by SA (Horvath and Chua, 1996; Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), antisense inhibition was evaluated after SA treatment of plantlets. Among the T1 progeny, two lines, AS 14 and AS 25, showed a considerable reduction in TOGT protein levels after treatment with SA (Figure 2A). The segregation analysis further indicated that these lines were single-locus insertions (data not shown). The inhibition was particularly evident in plants of the AS 14 line, in which TOGT was almost undetectable. The amount of residual TOGT protein was measured by quantifying the 52-kD TOGT bands revealed in protein gel blot experiments (Figure 2B). After treatment with SA, when the mean TOGT protein level of plants transformed with the empty vector was set to 100%, the mean TOGT protein levels of the AS 14 and AS 25 lines were 2 and 25%, respectively (Figure 2B). These results indicate that TOGT inhibition is significant among plants of the T1 progeny and show the efficiency of the antisense strategy, even after induction of the endogenous Togt genes.

Figure 2.

Screening of Transgenic Tobacco with Decreased TOGT Levels.

(A) Protein gel blot analysis of TOGT levels in control and TOGT antisense tobacco. Total proteins (3 μg) from leaves of plantlets treated for 16 h with 1 mM SA were analyzed by protein gel blot analysis with polyclonal anti-TOGT serum. Each lane represents an individual plant of the T1 progeny of the C4 and C1 lines (transformed with the empty vector) and the AS 14 and AS 25 lines (transformed with Togt in the antisense orientation).

(B) Relative intensity of the TOGT protein bands as shown in (A) after scanning the protein gel blot. Relative TOGT levels after SA treatment in antisense lines were calculated by comparison with the mean TOGT levels in control plants, which were set to 100%. Values are means ± se of three independent experiments.

TOGT Downregulation Leads to Decreased Scopoletin UGT Activity, Decreased Scopolin and Scopoletin Contents, and Alteration of the Blue Fluorescence Induced by Inoculation with Tobacco mosaic virus

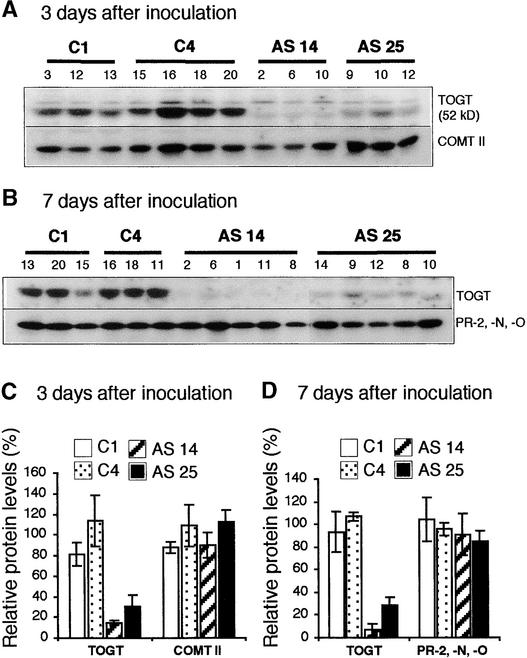

Togt genes are induced rapidly in tobacco after the onset of the HR triggered by Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) or a fungal elicitor (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), whereas no increase in TOGT is observed in TMV-inoculated leaves of susceptible tobacco cultivars (J. Chong, R. Baltz, and P. Saindrenan, unpublished results). Thus, TMV-inoculated plants of the resistant tobacco cv Samsun NN were used as the model system to study the role of TOGT during the induction of defense responses. We determined that TOGT inhibition in antisense adult plants inoculated with TMV was of the same magnitude as the inhibition measured in SA-treated plantlets (Figures 3C and 3D). Levels of residual TOGT protein after TMV inoculation were 7 to 14% and 28 to 30% of those of control plants for the AS 14 and AS 25 lines, respectively (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Analysis of TOGT Inhibition and of Typical Defense Markers in TOGT Antisense Plants Inoculated with TMV.

Total proteins (5 μg) from TMV-inoculated leaves were analyzed by protein gel blotting. Each lane represents an individual T1 plant of the control lines (C1 and C4, transformed with the empty vector) and the AS 14 and AS 25 lines (transformed with Togt in the antisense orientation).

(A) Protein gel blot analysis with anti-TOGT and anti-COMT II sera 3 days after inoculation.

(B) Protein gel blot analysis with anti-TOGT and anti-β-1,3-glucanase sera 7 days after inoculation. Anti-β-1,3-glucanase serum recognizes three isoforms, PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O.

(C) Relative intensity of the TOGT and COMT II protein bands as shown in (A) after scanning the protein gel blot. The mean TOGT and COMT II levels in control lines were set to 100%. Values are means ± se of TOGT and COMT II levels measured in three to four independent plants of the same line.

(D) Relative intensity of the TOGT and PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O protein bands as shown in (B) after scanning the protein gel blot. The mean TOGT and PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O levels in control lines were set to 100%. Values are means ± se of TOGT and PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O levels measured in three to five independent plants of the same line.

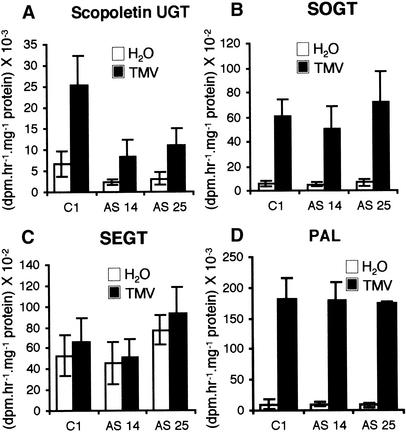

Because scopoletin and SA were shown to be a good and a poor in vitro substrate of recombinant TOGT, respectively (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), UGT activities were measured in control and antisense plants with scopoletin and SA as substrates. In control plants, scopoletin UGT activity exhibited a basal level in mock-inoculated leaves (Figure 4A) and was fourfold higher after TMV inoculation (Figure 4A). We found decreased UGT activity relative to controls with scopoletin as substrate in AS 14 and AS 25 lines in both H2O- and TMV-treated plants (Figure 4A). In TMV-inoculated leaves, the average scopoletin UGT activity was 33 and 43% of that of controls for the AS 14 and AS 25 lines, respectively. However, the induction factor between mock- and TMV-inoculated plants remained the same in antisense plants compared with controls (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Glucosyltransferase and PAL Activities in TOGT-Inhibited Plants.

Activities were measured in empty-vector (C1) and antisense (AS 14 and AS 25) lines 4 days after H2O (white) or TMV (black) inoculation. Values are means ± se of activities measured in six plants from the same line. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

(A) Glucosyltransferase activity forming scopolin.

(B) Glucosyltransferase activity forming SA β-O-d-glucoside.

(C) Glucosyltransferase activity forming salicyloyl Glc ester.

(D) PAL activity.

UGT activity toward SA could be separated into two activities: one forming the SA β-O-d-glucoside (SOGT) and one forming the salicyloyl Glc ester (SEGT). SOGT activity was very low in healthy plants and was strongly induced by TMV inoculation (Figure 4B), whereas SEGT activity displayed a high basal level in noninfected plants and was virtually the same after infection (Figure 4C). Neither SOGT nor SEGT activity was affected substantially in antisense plants relative to empty-vector controls (Figures 4B and 4C). The activity of Phe ammonia-lyase (PAL), the first enzyme of the phenylpropanoid pathway, also was induced to the same extent in the antisense and control lines (Figure 4D).

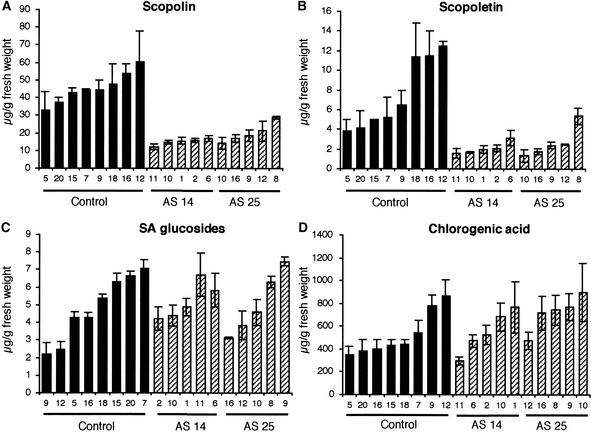

We further examined the effects of TOGT activity inhibition on the levels of soluble free and conjugated phenolic compounds in TMV-inoculated leaves 4 days after inoculation. Preliminary HPLC analyses of total soluble phenolic compounds coupled to fluorescence and UV light detection revealed that a peak corresponding to scopolin was reduced in the antisense lines. Scopolin and scopoletin thus were quantified more precisely in populations of plants from antisense and control lines (Figures 5A and 5B). In mock-inoculated control plants, levels of both scopolin and scopoletin were low (0.73 and 0.02 μg/g fresh weight, respectively). Mock-inoculated antisense transformants showed a twofold decrease in scopolin content compared with control plants (data not shown). In TMV-infected leaves of control plants, scopolin and scopoletin contents were maximal 4 days after inoculation, after the appearance of necrotic lesions.

Figure 5.

Scopolin and Scopoletin Are Reduced in TOGT-Depleted Plants after TMV Inoculation.

Phenolic compounds were determined by HPLC in 10-week-old control (C1 and C4 lines; black bars) and TOGT antisense (AS 14 and AS 25 lines; hatched bars) transformants 4 days after TMV inoculation. Values are means ± se of three independent experiments.

(A) Scopolin.

(B) Scopoletin.

(C) SA glucosides.

(D) Chlorogenic acid.

At the same time, plants of both the AS 14 and AS 25 lines displayed a significant (threefold to fourfold) decrease in scopolin amounts (Figure 5A). Unexpectedly, the pool of the aglycon scopoletin also was reduced in the inhibited plants (Figure 5B). As with scopolin, scopoletin content was threefold to fourfold lower in the antisense lines relative to controls. By contrast, levels of SA glucosides (SA β-O-d-glucoside and salicyloyl Glc ester) after infection were not affected significantly in TOGT-inhibited plants (Figure 5C), and no difference in free SA content between the different lines was observed (data not shown). Chlorogenic acid also accumulated to the same amounts in control and antisense plants (Figure 5D). The contents of ferulic acid and p-coumaric acid, which also are in vitro substrates of TOGT esterified to the cell wall, were analyzed after mild alkaline hydrolysis. However, no differences were found concerning these parietal components between control and TOGT-inhibited plants (data not shown).

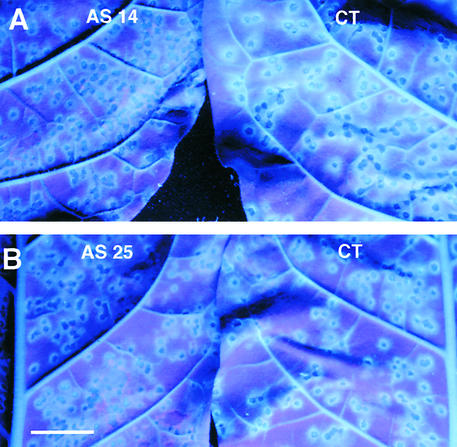

Three to 4 days after TMV inoculation, lesions of control plants observed under UV light were surrounded by a ring of cells characterized by bright blue fluorescence (Figures 6A and 6B). Recently, it was shown that scopolin and scopoletin, which accumulate to high levels during the necrotic response of tobacco to TMV, probably are the major compounds responsible for the blue fluorescence observed under UV light (Costet et al., 2002). Compared with controls, the blue fluorescence around the lesions in antisense plants was reduced dramatically and appeared more diffuse (Figures 6A and 6B). This phenotype demonstrates that the reduction of scopolin and scopoletin contents is reflected by an alteration of the blue fluorescence characterizing living cells adjacent to TMV lesions.

Figure 6.

TOGT Inhibition Leads to Alteration of the Blue Fluorescence around TMV Lesions under UV Light.

The blue fluorescence surrounding TMV lesions was revealed under UV light (365 nm) 4 days after inoculation in AS 14 (A) and AS 25 (B) plants. CT, empty vector–transformed plant. Bar = 2 cm.

Downregulation of TOGT by Antisense Expression Weakens Resistance to TMV

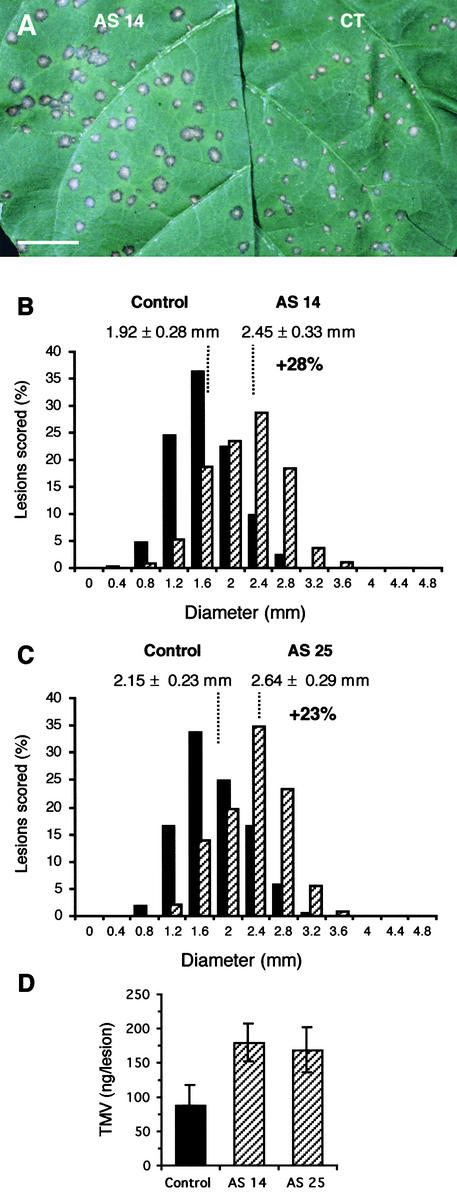

To gain further insight into the role of TOGT in defense response and pathogen resistance, we investigated the effect of antisense transformation on the local lesion response induced by the infection of Samsun NN tobacco with TMV. After TMV inoculation, the leaves of control and antisense lines were scored for disease symptoms (i.e., necrotic lesion size and lesion number). With regard to lesion number, we found no difference between the empty vector–transformed and antisense populations (data not shown). The lesions also appeared at the same time (from 36 to 48 h) in both populations and were indistinguishable in size between 40 and 72 h after inoculation. By contrast, the lesion size was increased significantly in antisense plants compared with controls by 6 to 8 days after inoculation (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Resistance to TMV Is Weakened in TOGT Antisense Plants.

(A) Aspect of lesions under visible light 7 days after TMV inoculation. CT, empty vector–transformed plant. Bar = 2 cm.

(B) and (C) Distribution of lesion sizes for the AS 14 and control populations (B) and for the AS 25 and control populations (C). Two leaves of plants from control lines (C1 and C4; black bars) and from antisense lines (AS 14 and AS 25; hatched bars) were inoculated with TMV and scored for lesion diameter on day 7. For each antisense and control line, 10 plants were inoculated and ∼1000 lesions were scored. Values are mean lesion sizes ± se for the number of lesions measured. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. The distributions of lesion sizes were normal, allowing the comparison of the mean lesion diameter for each population. The mean lesion sizes of the AS 14 and AS 25 populations were significantly different from that of the empty-vector population (Student's t test; P < 0.01).

(D) Effect of Togt antisense transformation on the amount of TMV measured in individual 7-day-old necrotic lesions. TMV was quantified by the double antibody sandwich form of ELISA (see Methods). Values are mean TMV amounts ± se measured in 30 lesions of control and TOGT-inhibited AS 14 and AS 25 populations.

Figures 7B and 7C show the distribution of lesion sizes 7 days after inoculation for the empty-vector controls and for the AS 14 and AS 25 lines. A mean diameter of 1.92 ± 0.28 mm was measured for the lesions of the empty vector–transformed population. For the AS 14 line, which displayed a 90% reduction in TOGT levels, the mean lesion diameter was 2.45 ± 0.33 mm, which corresponds to a statistically significant 28% increase in lesion diameter or a 63% increase in lesion surface relative to control plants (Figure 7B). An increase of 23% in lesion diameter was measured for the AS 25 line (Figure 7C).

Because lesion size is thought to reflect its viral content, we compared the amounts of TMV present in individual necrotic lesions of antisense and empty-vector plants. TMV amounts measured by ELISA in lesions of antisense plants were approximately twofold higher than those measured in lesions of control plants (Figure 7D). Together, these results clearly demonstrate that blocking Togt expression weakens the resistance to TMV infection and strongly suggest an active role for TOGT in the mechanism of resistance to TMV.

To determine if other components of defense responses might be modulated by TOGT inhibition, we tested by protein gel blot analysis the expression of two defense markers induced during the resistance response to TMV, the class II O-methyltransferase (COMT II) (Pellegrini et al., 1993) and acidic β-1,3-glucanases (PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O) (Kauffmann et al., 1987) (Figure 3). Figures 3A and 3C show the inhibition of TOGT accumulation in antisense lines 3 days after inoculation with TMV. COMT II accumulation was not affected significantly in either the AS 14 or the AS 25 line (Figures 3A and 3C). Acidic β-1,3-glucanases also accumulated to similar levels in leaves of control and antisense plants 7 days after TMV inoculation (Figures 3B and 3D). Thus, the effect of TOGT downregulation is specific and does not affect the intensity of expression of two typical markers associated with the HR, reflecting early (COMT II) and late (PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O) events of defense responses, respectively.

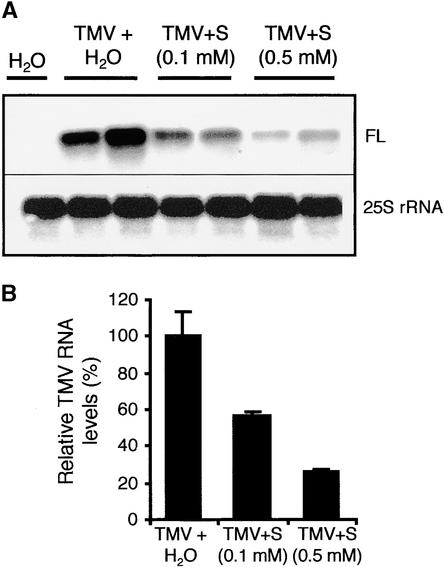

Scopoletin Inhibits TMV Replication in Infected Tobacco Protoplasts

To determine if decreased virus resistance could be related to scopolin/scopoletin depletion, we investigated whether this hydroxycoumarin could inhibit TMV replication in tobacco protoplasts. Tobacco BY2 protoplasts were treated with scopoletin or H2O immediately before their inoculation with TMV. The scopoletin concentrations used did not affect protoplast viability. The accumulation of TMV genomic RNA was examined 48 h after inoculation by RNA gel blot analysis using a cDNA probe specific for full-length TMV RNA (Figure 8). Treatment of protoplasts with scopoletin caused a significant reduction in the accumulation of TMV genomic RNA compared with treatment with H2O (Figure 8A). Quantification of the signal corresponding to TMV full-length RNA (Figure 8B) showed that the inhibitory effect of scopoletin was dose dependent: relative amounts of TMV genomic RNA were 57 and 25% of those of controls with 0.1 and 0.5 mM scopoletin, respectively (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Effect of Scopoletin on the Accumulation of TMV-Specific RNAs in TMV-Inoculated Tobacco Protoplasts.

(A) RNA gel blot analysis was performed with total RNA from healthy and TMV-inoculated tobacco protoplasts treated with H2O or scopoletin (final concentration, 0.1 or 0.5 mM). Protoplasts were treated with scopoletin or H2O immediately before electroporation with TMV and maintained in scopoletin-containing or standard medium for 48 h before harvest. Ten micrograms of total RNA was used per lane. The blot was hybridized successively with a cDNA probe corresponding to a fragment of the gene encoding the 126-kD protein of the replicase complex to detect full-length TMV RNA (FL) and with an Arabidopsis probe specific for 25S rRNA.

(B) Relative quantification of the band corresponding to TMV full-length RNA (FL) shown in (A).

S, scopoletin.

TMV-Induced ROI Accumulation Is Enhanced in TOGT-Inhibited Plants

We showed in a previous study that scopoletin is synthesized in tobacco cells upon elicitation of defense responses and transported as a glucoside to the extracellular space, where it is released in its free form by β-glucosidases (Chong et al., 1999). This extracellular free scopoletin could act as a direct scavenger of H2O2 deriving from the oxidative burst (Chong et al., 1999). To determine if decreased scopolin and scopoletin contents could enhance ROI accumulation in planta, we assayed tobacco plants for the production of ROIs in response to TMV infection. We used the sensitive fluorophore dichlorofluorescin (DCFH), which is oxidized to the highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in the presence of H2O2 and peroxidases, to measure increases in ROIs (Schopfer et al., 2001).

ROIs were measured on foliar discs centered on a single TMV lesion and including 2 mm of surrounding living tissue. To estimate specifically the increase in extracellular ROIs, we used the procedure developed by Schopfer et al. (2001) (see Methods). The kinetics of DCFH oxidation were first assayed with TMV-inoculated discs of wild-type Samsun NN plants 60 h after inoculation. To confirm that DCF fluorescence was indicative of the oxidative burst, we used several ROI inhibitors. Table 1 shows that DCFH oxidation by TMV-inoculated leaf discs could be inhibited by a general antioxidant (Na-ascorbate), by a H2O2 scavenger (catalase), and by peroxidases and NADPH oxidase inhibitors (NaN3 and diphenylene iodonium, respectively). The kinetics of DCFH oxidation then were assayed with TMV-inoculated leaf discs of antisense and control plants 60 and 96 h after inoculation as well as with discs of water-inoculated leaves (Figure 9). No ROI release was measured with discs from nontreated plants (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of ROI Inhibitors on ROI Production by TMV-Inoculated Leaf Discs

| Inhibitor | ROI Production (%) |

|---|---|

| None | 100 ± 2 |

| Catalase (100 μg/ml) | 46 ± 8 |

| Na-ascorbate (10 mM) | 41 ± 3 |

| DPI (100 μM) | 55 ± 1 |

| NaN3 (1 mM) | 50 ± 1 |

The ROI-dependent oxidation of DCFH by 20 TMV-inoculated leaf discs from Samsun NN tobacco 60 h after inoculation was determined after an incubation period of 30 min with DCFH in the presence of various inhibitors. The lesions were preincubated in the inhibitor solution for 15 min before the addition of DCFH. DPI, diphenylene iodonium.

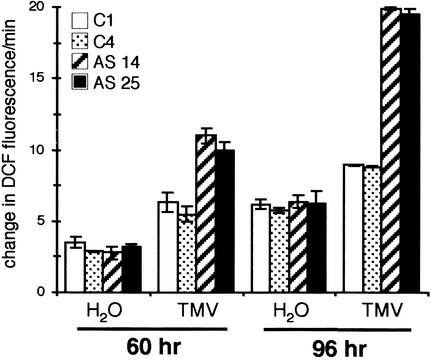

Figure 9.

Decreased Scopolin and Scopoletin Pools in TOGT Antisense Lines Are Correlated with Higher ROI Accumulation after TMV Inoculation.

Time course of DCFH oxidation was determined with 20 TMV- or H2O-inoculated leaf discs 60 and 96 h after inoculation. White bars show the control C1 line, stippled bars show the control C4 line, hatched bars show the antisense AS 14 line, and black bars show the antisense AS 25 line. Values are means ± se of three independent experiments.

In mock-inoculated discs, an increase in ROIs was measured, as a consequence of the effect of wounding with the abrasive, but no difference in ROI accumulation was detected between antisense and control plants (Figure 9). TMV inoculation of control plants induced a greater extracellular ROI accumulation than H2O treatment (Figure 9). However, compared with control plants, the extracellular ROI increase reflected by DCFH oxidation was significantly higher when measured on TMV-inoculated leaf discs from antisense plants (Figure 9). The slopes of curves of DCF fluorescence showed 1.5- and 2.2-fold increases in DCFH oxidation compared with controls in the incubation medium of TOGT-depleted lesions at 60 and 96 h after TMV inoculation, respectively (Figure 9). Hence, the most pronounced differences in ROI accumulation between antisense and control plants were measured 96 h after virus inoculation. Remarkably, they were correlated with the differences in blue fluorescence that developed around lesions and with the changes in scopoletin pools that were observed concomitantly.

DISCUSSION

TOGT Is Involved in Scopoletin Glucosylation

By regulating the solubility, biological activity, and transport of compounds within the cell, glucosyltransferases are crucial in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Despite the number of plant secondary product UGTs, the direct demonstration of their function by altering their expression in transgenic plants has been reported only rarely. Here, we show that inhibition of TOGT, a phenylpropanoid glucosyltransferase acting mostly on hydroxycoumarins in vitro (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), suppressed the accumulation of scopolin by 70 to 75% in tobacco reacting hypersensitively to TMV (Figure 5). Moreover, the close correlation between scopolin depletion and reduced scopoletin UGT activity in the inhibited lines strongly supports the requirement of TOGT for scopoletin glucosylation. Interestingly, the levels of the free form (scopoletin) were reduced to the same extent as the levels of scopolin in inhibited transformants, although one would expect that the inhibition of the conjugation step would trigger the accumulation of the corresponding free form.

Several hypotheses could explain this unexpected reduced scopoletin content. First, it is known that phenolic compounds cannot accumulate to high levels as aglycons in plant cells, because they are very reactive and subject to oxidation. Scopoletin is a reactant of peroxidases in vitro and in vivo (Chong et al., 1999), and it is likely that compromising scopoletin glucosylation could enhance its degradation by cellular oxidases. Second, one part of the scopoletin pool may arise from the cleavage of the glucosylated form (scopolin) by β-glucosidases (Figure 1), as proposed recently for elicited tobacco cells (Chong et al., 1999). The mobilization of the free forms from a pool of conjugated phenolic compounds also was reported in the case of resveratrol glucoside in transgenic alfalfa (Hipskind and Paiva, 2000) and for SA β-O-d-glucoside in tobacco (Seo et al., 1995). Third, TOGT inhibition could alter metabolic flux toward the conjugated form (scopolin), resulting in the feedback inhibition of upstream enzymes of scopoletin biosynthesis.

Studies of transgenic plants downregulated for COMT I, an enzyme involved in lignin biosynthesis, revealed that COMT I inhibition also reduces the expression of caffeoyl CoA-methyltransferase, an enzyme situated upstream of COMT I in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Martz et al., 1998). However, in TOGT antisense lines, PAL induction triggered by infection was the same as that in the control lines, and other phenolic compounds depending on PAL were not modified. Moreover, COMT II is active toward caffeoyl CoA in vitro and might be involved in the synthesis of ferulic acid derivatives (Maury et al., 1999), which are potential precursors of scopoletin (Fritig et al., 1970). The accumulation of COMT II was not modified in TOGT antisense lines after TMV inoculation.

Together, these results do not support an eventual inhibition of other enzymes of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in TOGT downregulated plants, although the inhibition could affect specific enzymes of scopoletin biosynthesis, which are not known. In conclusion, the modification of the scopoletin pool in TOGT-depleted plants strongly suggests that glucosylation is necessary for the accumulation of phenylpropanoids.

The reduction of scopolin and scopoletin contents resulting from TOGT inhibition after TMV infection was correlated with a spectacular reduction of the blue fluorescence in cells surrounding the virus lesions (Figure 6). Scopolin certainly is the major compound responsible for this fluorescence in tobacco, because this coumarin glucoside, which displays strong blue fluorescence, accumulates to very high levels compared with other phenylpropanoids (apart from chlorogenic acid) in the ring of stimulated cells surrounding TMV lesions (Tanguy and Martin, 1972). Moreover, other studies in our laboratory showed that most of the blue fluorescence around HR cells in tobacco was associated with scopolin and scopoletin (Costet et al., 2002).

Other phenolic compound pools that are induced upon infection, such as free SA and SA glucosides (Lee and Raskin, 1998), chlorogenic acid (Tanguy and Martin, 1972), and wall-bound hydroxycinnamic acids, were not affected in TOGT antisense lines. With regard to the SA glucosides, the results are correlated with the glucosyltransferase activities obtained in planta (this study) and in vitro on recombinant TOGT, which exhibits low activity toward SA (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). Recombinant TOGT also produces the Glc esters of p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). Glucosylation of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives is thought to activate the acyl moiety for trans-esterification into the cell wall followed by cross-linking into phenolic polymers (Hahlbrock and Scheel, 1989). However, TOGT inhibition did not affect the wall-bound phenolic profiles of TMV-inoculated leaves after mild alkaline hydrolysis, suggesting that TOGT would not be involved in the production of cell wall impregnation precursors.

In conclusion, our data clearly demonstrate the function in planta of TOGT in scopoletin glucosylation and further indicate that although SA was found to be a strong inducer of Togt expression (Horvath and Chua, 1996; Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998), this UGT apparently is not required for the regulation of the SA signal during plant defense responses. Nevertheless, it should be noted that even when TOGT expression was nearly suppressed in the AS 14 line, the scopolin content was not depleted completely. Similarly, a basal level of scopoletin UGT activity remained in antisense plants. These results indicate that other UGTs may exist in tobacco that are active toward scopoletin, although perhaps with less affinity than TOGT. In support of this idea, a novel glucosyltransferase from tobacco with 45% similarity to TOGT that preferentially glucosylates flavonoids in vitro and to a lesser extent coumarins such as scopoletin was characterized recently (Taguchi et al., 2001).

TOGT Is Required for Full Resistance to TMV

The experiments described here also present direct evidence of the important role of a UGT in virus resistance. We show that a deficiency in TOGT decreased the resistance of tobacco to TMV infection, as determined by the significant increase in lesion surface (+60%) and by the twofold increase in the amount of TMV accumulation in the necrotic lesions. The phenotype of the antisense lines could be associated specifically with TOGT depletion. Indeed, the antisense plants did not seem to be affected significantly in mounting other typical defense reactions, such as the induction of enzymes involved in lignification (COMT II) and the accumulation of pathogenesis-related proteins (β-1,3-glucanases). However, if we consider that the number of TMV-stimulated cells by day 7 after inoculation is enhanced to some extent by the larger size of the lesions in the antisense lines, the accumulation of β-1,3-glucanases should be higher in these plants, but this augmentation probably is too slight to be revealed by protein gel blot analysis.

In tobacco reacting hypersensitively to TMV, the cells beyond necrotic lesions still contain infectious virus particles (Konate et al., 1982). This observation shows that hypersensitive cell death is not sufficient to restrict pathogen spread and that defense responses induced in living cells that surround HR cells are required for full pathogen containment. Dorey et al. (1997) showed that during the HR induced by a fungal elicitor, a low and transient increase was found in total scopoletin in HR cells, whereas a strong accumulation was measured in cells adjacent to the necrosis. Our work strongly suggests that decreased resistance to TMV in antisense lines is a consequence of reduced scopolin and scopoletin contents, principally in living cells surrounding the necrotic zone, which contribute to pathogen spread limitation.

There is substantial evidence that scopolin and scopoletin play an important role in plant disease resistance. Earlier studies demonstrated that scopolin accumulates only in TMV-resistant cultivars after inoculation (Tanguy and Martin, 1972). Moreover, it has been shown that scopoletin possesses antimicrobial activity in vitro and therefore can be considered a phytoalexin (Ahl-Goy et al., 1993; Kuc, 1995). Increased constitutive levels of scopolin and scopoletin also were measured in a Nicotiana hybrid that is resistant to viral, bacterial, and fungal diseases (Ahl-Goy et al., 1993). Phytoalexins generally are believed to exert their antimicrobial activity toward fungi and bacteria. However, our work provides evidence that exogenous scopoletin, at concentrations similar to those of total scopoletin around HR lesions (∼250 μM), was able to inhibit TMV replication in tobacco protoplasts. Thus, scopoletin accumulation could be part of the mechanism of virus restriction in planta.

It is known that phenolic compounds display antiviral activity, especially against animal viruses. For example, phenolic moieties, and particularly compounds containing 4-hydroxycoumarin residues, are inhibitors of the Human immunodeficiency virus integrase required for virus replication (Mazumder et al., 1996). A few studies have demonstrated the antiviral activity of phenylpropanoids toward plant viruses. However, a range of flavonoids inhibit the infectivity of TMV (French et al., 1991). SA also was shown to interfere with TMV replication in compatible interactions with tobacco (Chivasa et al., 1997) and to inhibit the replication of Alfalfa mosaic virus in cowpea protoplasts (Hooft van Huijsduijnen et al., 1986). Thus, the higher virus content in TOGT-inhibited plants may be a consequence of the reduction of the antiviral scopoletin pool, which would allow enhanced TMV replication and accumulation in cells adjacent to HR lesions.

Scopoletin May Represent an Antioxidant in Living Cells Surrounding HR Lesions

Besides the possible antiviral role of scopoletin investigated in this study, this molecule likely represents a potent antioxidant in plant defense responses (Chong et al., 1999), together with scopolin, which can act as a source of scopoletin after its hydrolysis by β-glucosidases. ROIs (O2.− or H2O2) generated via the oxidative burst have been proposed to play a central role in the development of host cell death during the HR (Dangl et al., 1996). Indeed, programmed cell death during the HR was enhanced in transgenic plants with reduced levels of ascorbate peroxidase or catalase, which are unable to properly remove ROIs (Mittler et al., 1999).

It also has been proposed that high levels of ROIs induce cell death typical of HR, whereas lower levels, such as those found at the lesion margin, activate the transcription of genes that code for enzymes involved in the resistance to oxidative damage (e.g., glutathione S-transferases and glutathione peroxidases) (Jabs et al., 1996; Lamb and Dixon, 1997). This arrangement would regulate ROI accumulation, limit the extent of necrosis, and maintain the capacity of surrounding cells to deploy transcription-dependent defenses (Lamb and Dixon, 1997). Thus, it was reported in tobacco that catalase expression and activity decreased in HR cells, whereas catalase activity was induced in living cells beyond HR lesion (Dorey et al., 1998).

Many hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives also can act as scavengers of O2.−, and ascorbate-dependent peroxidases acting on phenolic substrates may remove H2O2 from the apoplasm (Lamb and Dixon, 1997). Our study suggests the hypothesis that scopoletin, together with other antioxidant systems, plays a role in the regulation of ROI accumulation in living cells surrounding necrotic lesions, either as a substrate of peroxidases or as a direct ROI scavenger. This idea is supported by ROI measurements on TMV infected tissues, which revealed a more intense ROI accumulation relative to controls, in antisense plants also characterized by a reduction of antioxidant scopolin and scopoletin pools.

Interestingly, the role of phenolic compounds as endogenous antioxidants has been emphasized in recent work demonstrating that the inhibition of phenolic acid metabolism triggered premature cell death in tobacco leaves, suggesting that the oxidation of phenolic compounds is part of a protective mechanism that reduces the impact of increased ROI levels during senescence (Tamagnone et al., 1998). Moreover, transgenic tobacco plants that accumulate tetrapyrrole intermediates were found to accumulate scopolin constitutively in their leaves (Mock et al., 1999). Because it is known that the toxicity of tetrapyrroles is exerted via ROIs (Mock et al., 1999), scopolin accumulation could represent a means to withstand ROIs in these plants. Our results obtained with TOGT transgenic plants further support the idea of the participation of antioxidant hydroxycoumarins in the control of ROI accumulation during plant–pathogen interactions.

H2O2 has been proposed to act as a signal that activates plant defense responses (Lamb and Dixon, 1997) and resistance in the case of the interaction with avirulent bacteria (Alvarez et al., 1998). The enhanced ROI accumulation in TOGT-downregulated lines may have been expected to enhance the expression of host defense responses and virus resistance. However, it should be noted that H2O2 contents may not be limiting for the induction of defense responses in wild-type plants. Thus, the 1.5- to 2-fold increase in H2O2 observed in antisense plants does not necessarily trigger an increase in defense gene expression. Moreover, because TOGT is likely to play a role in living cells adjacent to HR lesions, the increase in ROI accumulation in inhibited plants does not contradict the decreased TMV resistance. Indeed, ROI accumulation in neighboring cells must be controlled tightly to limit the effects of the oxidative stress and to allow the full expression of defense responses toward TMV.

Conclusion

Our work provides clear evidence of the biological role of a phenylpropanoid UGT in plant defense responses and demonstrates the importance of TOGT in the control of free and conjugated scopoletin pools. This study also sheds new light on the importance of glucosylation in the accumulation of phenylpropanoids that play a dual role in plant defense, as both antiviral agents and antioxidant compounds involved in the maintenance of the cellular redox state. Two nonexclusive hypotheses could explain the phenotype of TOGT antisense lines after virus infection. The greater number of dead cells and the higher virus content reflected by the enlarged lesions may be a consequence of increased virus replication and/or enhanced oxidative stress.

METHODS

Chemicals

Salicylic acid (SA), scopoletin, chlorogenic acid, and UDP-Glc were from Sigma Aldrich Chimie (St. Quentin-Fallavier, France). SA β-O-d-glucoside and salicyloyl Glc ester were kindly provided by Prof. S. Tanaka (University of Kyoto, Japan). Scopolin was obtained enzymatically with recombinant tobacco SA– and pathogen-inducible UGT (TOGT) (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998). 7-14C-Salicylic acid (2 GBq/mmol) and UDP-d-U-14C-Glc (10.6 GBq/mmol) were obtained from DuPont–New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). Dichlorofluorescin-diacetate (DCFH-DA; Sigma) was dissolved in 100% ethanol to produce a 100 mM stock.

Vector Construction

All DNA recombinant procedures were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). The binary vector pFB8 (Atanassova et al., 1995) contains a bacterial neomycin phosphotransferase II gene as a plant-selectable kanamycin resistance marker. The Togt1 full-length cDNA (1428 bp) (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998) was isolated from a pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI). A Togt polymerase chain reaction fragment was generated using primers 5′-GTCCCCCGGATCCTAGACATGGGTCAGCTCCATTTTTTC-3′ and 5′-GCCGCTCGAGCTCTTAATGACCAGTAGAACTATATG-3′ (priming at positions +1 and +1428 relative to the ATG start codon of Togt1, respectively), introducing a XhoI site at the 3′ end and a BamHI site at the 5′ end of the coding region. The fragment was cloned in the antisense orientation downstream from the 420-bp 35S RNA promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus in the XhoI-BamHI sites of pFB8 vector. The binary vector was mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 by electroporation. The integrity of the vector was verified directly by polymerase chain reaction on Agrobacterium.

Plant Transformation and Regeneration

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Samsun NN) was transformed via Agrobacterium and regenerated by a modification of the leaf disc method as described previously (Atanassova et al., 1995). Forty independent transformants were regenerated as well as 20 independent plants transformed with the empty (without insert) vector as controls. The primary transformants (T0) were first screened by protein gel blot analysis for reduced TOGT protein levels in plantlet leaves treated with SA (data not shown). Plantlets of the inhibited lines were transferred to the greenhouse and cultivated in soil under a light/dark period of 16/8 h at 22 ± 4°C until flowering. Plants were allowed to self-pollinate, and T1 seeds were harvested and selected further on germination medium containing kanamycin. The T1 progeny were used in all of the experiments described.

Infection of Tobacco Leaves and Protoplasts with Tobacco mosaic virus

For plant infection, 10-week-old transgenic plants cultivated in the greenhouse were inoculated by rubbing fully expanded leaves with a suspension of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) (U1 strain; 0.1 μg/mL) in water containing celite powder as an abrasive. Leaves rubbed with an aqueous celite suspension were used as wounded controls. Leaves were harvested at different times after inoculation, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

For protoplast infection, the tobacco BY2 cell line was cultured as described by Nagata et al. (1992). Protoplasts were prepared as described by Gaire et al. (1999) and resuspended in 3.6 mM 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.5, containing 0.45 M mannitol and 0.1 mM CaCl2 (solution A). Scopoletin was dissolved in DMSO to produce a stock solution (1 M) and was added to protoplasts to a final concentration of 0.1 or 0.5 mM immediately before electroporation. Control protoplasts were treated with DMSO alone at the same concentration.

Protoplasts (1 × 106 in 0.5 mL) were electroporated with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a 0.4-cm-path-length cuvette at 0.18 kV, 100 Ω, and 125 μF using 1 μg of purified TMV (U1 strain). After electroporation, 1 mL of solution A was added, and the protoplasts were incubated for 30 min on ice before sedimentation. Protoplasts then were cultured at 25°C in 1.5 mL of BY2 culture medium plus 0.45 M mannitol in the presence or absence of scopoletin in 35-mm-diameter Petri dishes containing a bottom layer of 1% agarose. Protoplasts were collected carefully after 48 h by centrifugation at 40g.

SA Treatment

Leaves of 6-week-old in vitro–grown plants were excised, allowed to imbibe a solution of 1 mM potassium salicylate, pH 6.5, and kept under light at 25°C for 16 h. SA-treated leaves were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C.

Protein Gel Blot Analysis

Foliar explants were harvested from 6-week-old in vitro–regenerated T1 plants treated with SA or from 10-week-old TMV-inoculated T1 plants cultivated in the greenhouse. Samples (0.5 g) were ground in liquid N2 and extracted with 1.5 mL of 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 28 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 1% polyclar AT. SDS-PAGE was performed according to standard procedures. Proteins were blotted on Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) as described previously (Baillieul et al., 1995). Detection was realized with the Immun-Star Chemiluminescent Kit (Bio-Rad).

Polyclonal antibodies raised against recombinant TOGT produced in Escherichia coli (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998) were used at a dilution of 1:10,000. Relative TOGT protein amounts were quantified by scanning the protein gel blot and measuring the relative intensity of the 52-kD band corresponding to TOGT using MacBAS software (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan). Polyclonal antibodies raised against class II O-methyltransferase (Pellegrini et al., 1993) and against three acidic β-1,3-glucanase isoforms (PR-2, PR-N, and PR-O) (Kauffmann et al., 1987) purified from tobacco were used at dilutions of 1:5000 and 1:2000, respectively.

Glucosyltransferase and Phe Ammonia-Lyase Activity Measurements

Phe ammonia-lyase activity was extracted and measured as described by Pellegrini et al. (1993). For UGT activity, samples (1 g) were extracted as described by Chong et al. (1999). Scopoletin UGT and SA UGT activities were performed with 30 μL of concentrated extract in 50 μL of reaction mixture containing 100 μM scopoletin, 110 μM UDP-14C-Glc (10.6 GBq/mmol) or 180 μM 7-14C-SA (2 GBq/mmol), and 200 μM unlabeled UDP-Glc. Incubations were terminated by the addition of 50 μL of methanol (MeOH). Reaction products were analyzed on 0.25-mm silica gel thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates according to Fraissinet-Tachet et al. (1998). Radioactivity on TLC plates was visualized and quantified with a Bio-Imager analyzer (Fuji). Reaction products were identified by a combination of cochromatography on TLC plates with authentic compounds and analysis by HPLC with a photodiode array detector (Millenium software; Waters, Milford, MA) as described previously (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998).

Determination of Phenolic Compounds

Plant material (0.5 g) was extracted twice with 1 mL of 90% (v/v) MeOH. Aqueous MeOH was removed under N2, and the dried residue was dissolved in 300 μL of 5% acetonitrile in 25 mM NaH2PO4, pH 3.0, before HPLC analysis. 4-Methylumbelliferone (1 nmol) was added to each sample before extraction as an internal standard. HPLC analysis was performed on a C18 Nova Pak column (particle size, 5 μm; 4.6 × 150 mm; Waters) using a gradient of 25 mM CH3CN in NaH2PO4, pH 3, at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The gradient was 5 to 22% for 35 min and then 22 to 80% for 1 min. Scopolin and scopoletin (retention times, 16.5 and 26.5 min, respectively) were detected by fluorescence (excitation, 290 nm; emission, 402 nm). Chlorogenic acid (retention time, 15 min) was detected by UV light spectrophotometry at 280 nm. Free and conjugated SA were extracted and detected by fluorescence (excitation, 315 nm; emission, 405 nm) as described by Baillieul et al. (1995). Identification of the compounds was further based on cochromatography with authentic standards coupled to a photodiode array detector (detection between 230 and 400 nm; Waters Millenium software). Compounds were quantified by comparison with reference compounds.

Extraction of Total RNA from Infected Tobacco Protoplasts and Detection of Viral RNA

A cDNA probe specific for the TMV genome was used to detect TMV genomic RNA synthesized in protoplasts. The MluI-NheI cDNA fragment (1111 bp) of the TMV 30 B vector (Shivprasad et al., 1999) corresponding to a fragment of the gene encoding the 126-kD protein of the replicase complex was labeled by random priming with 32P-dCTP using Ready-To-Go labeling beads from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech according to the supplier's instructions. Protoplasts (1 × 106) were disrupted in 500 μL of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM LiCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS. Total RNA was extracted twice with phenol:chloroform (1:1, v/v) and precipitated for 12 h on ice with 0.2 M LiCl. The pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in H2O. Total RNA (10 μg) was separated by electrophoresis on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel and blotted for 12 h with 10 × SSC (1 × SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate) to a Hybond N+ membrane. The membrane was hybridized successively according to standard protocols (Sambrook et al., 1989) with the 126-kD probe and with an Arabidopsis 25S rRNA probe provided by the ABRC (Columbus, OH).

Quantification of TMV in Plant Tissue by ELISA

Discs of tissue were cut to a diameter of 6 mm from the center of individual lesions of 7-day-inoculated tobacco leaves. Individual lesions were extracted with 250 μL of 100 mM potassium buffer, pH 6, containing 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for TMV detection. Approximately 30 lesions were tested for each line of antisense and control plants.

The “double antibody sandwich” form of ELISA was used. Polystyrene microtiter plates (microlon 96K; Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) were coated overnight with a solution of chicken anti-TMV IgG (2 μg/mL) in 0.5 M sodium carbonate, pH 9.8. Saturation of aspecific sites was achieved with 1% BSA in PBS-Tween for 1 h at 37°C. Different dilutions in PBS-Tween of the crude extract of lesions (1:20, 1:100, and 1:500) were kept in the wells for 2 h at 37°C. Plates were incubated further with the second antibody (i.e., rabbit anti-TMV IgG; 10 μg/mL) for 2 h. Goat anti-rabbit antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase (2 μg/mL; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) then were added for 1 h. Alkaline phosphatase activity was revealed by adding p-nitrophenylphosphate (1 mg/mL) in 0.1 M diethanolamine buffer, pH 9.8. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm. Plates were washed three times between each step with PBS buffer containing 0.05% Tween. TMV concentration in each extract was determined by comparison with a standard curve obtained with solutions of 1 to 250 ng/mL purified TMV.

In Vivo Detection of H2O2 in Plants

Leaves of 10-week-old antisense and control plants were inoculated with TMV on one half and with water on the other half. Tissue discs were cut to a diameter of 6 mm from the center of individual lesions 60 or 96 h after inoculation. Discs of the same size from water-inoculated half leaves were used as wounded controls. Plants were maintained in the dark for 2 h before harvest to obtain low basal levels of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs). DCFH can be introduced into the cell as esterified DCFH-DA, where it is deacetylated by endogenous esterases and trapped as DCFH, a nonfluorescent compound. To measure increases in extracellular ROIs, the method developed by Schopfer et al. (2001) was used. This method consists of deacetylating DCFH-DA to the membrane-impermeant DCFH before adding it to necrotic lesions incubated in phosphate buffer. In this way, the ROI-dependent oxidation of DCFH to dichlorofluorescein (DCF) reflects the extracellular oxidative burst and can be measured by the increase in DCF fluorescence in the liquid incubation medium of leaf discs.

A 10 mM solution of DCFH-DA in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, was incubated in the dark for 40 min at 25°C with 2 g/L esterase (from hog liver; Sigma Aldrich Chimie) for deacetylation. Before ROI assays, foliar discs were preincubated for 1 h in Petri dishes containing 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6, to remove preformed ROIs. ROI assays then were performed by incubating 20 discs in 6 mL of 100 μM deacetylated DCFH in potassium phosphate buffer at 25°C on a shaker in darkness. At different times after the addition of DCFH, a 1-mL aliquot of the solution was removed, and the increase in fluorescence (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 525 nm) indicating the ROI-dependent oxidation of DCFH to DCF was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Shimadzu RF-500, Kyoto, Japan). ROI inhibitors (catalase and diphenylene iodonium) were obtained from Sigma. The lesions were preincubated in the inhibitor solution for 15 min before the addition of DCFH.

Accession Number

The GenBank accession number for the Togt1 full-length cDNA is AF346431.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Shigeo Tanaka (University of Kyoto) for kindly providing the SA glucosides, to Céline Waeber and Magali Feucht for technical help, and to the ABRC for providing an expressed sequence tag clone corresponding to 25S rRNA. Special thanks to Pierrette Geoffroy for the determination of PAL activity. We thank Richard Wagner, Michel Kerneis, and Sebastien Sterck for taking good care of transgenic tobacco plants. Drs. Thierry Heitz, Marc-Henri Lebrun, Jean-Benoît Morel, and Claire Gachon are thanked for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable discussions. This work was supported by postdoctoral Aventis fellowships (to R.B. and C.S.) and by Grant 97-5-11603 from the French Ministry of Education and Research to J.C.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010436.

References

- Ahl-Goy, P., Signer, H., Reist, R., Aichholz, R., Blum, W., Schmidt, E., and Kessmann, H. (1993). Accumulation of scopoletin is associated with the high disease resistance of the hybrid Nicotiana glutinosa × Nicotiana debneyi. Planta 191, 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.E., Pennell, R.I., Meijer, P., Ishikawa, A., Dixon, R.A., and Lamb, C. (1998). Reactive oxygen intermediates mediate a systemic signal network in the establishment of plant immunity. Cell 92, 773–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanassova, R., Favet, N., Martz, F., Chabbert, B., Tollier, M., Monties, B., Fritig, B., and Legrand, M. (1995). Altered lignin composition in transgenic tobacco expressing O-methyltransferase sequences in sense and antisense orientation. Plant J. 8, 465–477. [Google Scholar]

- Baillieul, F., Genetet, I., Kopp, M., Saindrenan, P., Fritig, B., and Kauffmann, S. (1995). A new elicitor of the hypersensitive response in tobacco: A fungal glycoprotein elicits cell death, expression of defense genes, production of salicylic acid, and induction of systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 8, 551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivasa, S., Murphy, A.M., Naylor, M., and Carr, J.P. (1997). Salicylic acid interferes with tobacco mosaic virus replication via a novel salicylhydroxamic acid–sensitive mechanism. Plant Cell 9, 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J., Baltz, R., Fritig, B., and Saindrenan, P. (1999). An early salicylic acid-, pathogen- and elicitor-inducible tobacco glucosyltransferase: Role in compartmentalization of phenolics and H2O2 metabolism. FEBS Lett. 458, 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J., Pierrel, M.-A., Atanassova, R., Werck-Reichhart, D., Fritig, B., and Saindrenan, P. (2001). Free and conjugated benzoic acid in tobacco plants and cell cultures: Induced accumulation upon elicitation of defense responses and role as salicylic acid precursors. Plant Physiol. 125, 318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquoz, J.-L., Buchala, A., and Métraux, J.-P. (1998). The biosynthesis of salicylic acid in potato plants. Plant Physiol. 117, 1095–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costet, L., Fritig, B., and Kauffmann, S. (2002). Scopoletin expression in elicitor-treated and tobacco mosaic virus infected plants. Physiol. Plant., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dangl, J.L., Dietrich, R.A., and Richberg, M.H. (1996). Death don't have no mercy: Cell death programs in plant–microbe interactions. Plant Cell 8, 1793–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Ukness, S., Vernooij, B., Friedrich, L., Weymann, K., Negrotto, N., Gaffney, T., Gut-Rella, M., Kessmann, H., Ward, E., and Ryals, J. (1994). A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 266, 1247–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R.A., and Paiva, N.L. (1995). Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell 7, 1085–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey, S., Baillieul, F., Pierrel, M.-A., Saindrenan, P., Fritig, B., and Kauffmann, S. (1997). Spatial and temporal induction of cell death, defense genes, and accumulation of salicylic acid in tobacco leaves reacting hypersensitively to a fungal glycoprotein elicitor. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10, 646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Dorey, S., Baillieul, F., Saindrenan, P., Fritig, B., and Kauffmann, S. (1998). Tobacco class I and II catalases are differentially expressed during elicitor-induced hypersensitive cell death and localized acquired resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff, N.V., Furtek, D.B., and Nelson, O.E. (1984). Cloning of the bronze locus in maize by a simple and generalizable procedure using the transposable controlling element Activator (Ac). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 3825–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C.M., Boss, P.K., and Hoj, P.B. (1998). Cloning and characterization of Vitis vinifera UDP-glucose:flavonoid-3-O-glucosyltransferase, a homologue of the enzyme encoded by the maize Bronze-1 locus that may primarily serve to glucosylate anthocyanidins in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9224–9233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraissinet-Tachet, L., Baltz, R., Chong, J., Kauffmann, S., Fritig, B., and Saindrenan, P. (1998). Two tobacco genes induced by infection, elicitor and salicylic acid encode glucosyltransferases acting on phenylpropanoids and benzoic acid derivatives, including salicylic acid. FEBS Lett. 437, 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French, C.J., Elder, M., Leggett, F., Ibrahim, R.K., and Towers, G.H.N. (1991). Flavonoids inhibit infectivity of tobacco mosaic virus. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fritig, B., Heitz, T., and Legrand, M. (1998). Antimicrobial proteins in induced plant defense. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10, 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritig, B., Hirth, L., and Ourisson, G. (1970). Biosynthesis of the coumarins: Scopoletin formation in tobacco tissue cultures. Phytochemistry 9, 1963–1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney, T., Friedrich, L., Vernooij, B., Negrotto, D., Nye, G., Uknes, S., Ward, E., Kessmann, H., and Ryals, J. (1993). Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 261, 754–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaire, F., Schmitt, C., Stussi-Garaud, C., Pinck, L., and Ritzenthaler, C. (1999). Protein 2A of grapevine fanleaf nepovirus is implicated in RNA2 replication and colocalizes to the replication site. Virology 264, 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahlbrock, K., and Scheel, D. (1989). Physiology and molecular biology of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Resistance gene–dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 8, 1773–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X.-Z., and Dixon, R.A. (2000). Genetic manipulation of isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase enhances biosynthesis of 4′-O-methylated isoflavonoid phytoalexins and disease resistance in alfalfa. Plant Cell 12, 1689–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig, J., Malamy, J., Grynkiewicz, G., Indulsky, J., and Klessig, D.F. (1993). Interconversion of the salicylic acid signal and its glucoside in tobacco. Plant J. 4, 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipskind, J.D., and Paiva, N.L. (2000). Constitutive accumulation of a resveratrol-glucoside in transgenic alfalfa increases resistance to Phoma medicaginis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani, M., Kuroda, R., Suzuki, H., and Yoshikawa, T. (2000). Cloning and expression of UDP-glucose:flavonoid-7-O-glucosyltransferase from hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. Planta 210, 1006–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooft van Huijsduijnen, R.A.M., Alblas, S.W., De Rijk, R.H., and Bol, J.F. (1986). Induction by salicylic acid of pathogenesis-related proteins and resistance to alfalfa mosaic virus infection in various plant species. J. Gen. Virol. 67, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, D.M., and Chua, N.H. (1996). Identification of an immediate-early salicylic acid-inducible tobacco gene and characterization of induction by other compounds. Plant Mol. Biol. 31, 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs, T., Dietrich, R.A., and Dangl, J.L. (1996). Initiation of runaway cell death in an Arabidopsis mutant by extracellular superoxide. Science 273, 1853–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann, S., Legrand, M., Geoffroy, P., and Fritig, B. (1987). Biological function of pathogenesis-related proteins: Four PR proteins of tobacco have a β-1,3-glucanase activity. EMBO J. 6, 3209–3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konate, G., Kopp, M., and Fritig, B. (1982). Multiplication du virus de la mosaïque du tabac dans des hôtes systémiques ou nécrotiques: Approche biochimique à l'étude de la résistance hypersensible aux virus. Phytopathol. Z. 105, 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kuc, J. (1995). Phytoalexins, stress metabolism, and disease resistance in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 33, 275–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C., and Dixon, R.A. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 251–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.I., and Raskin, I. (1998). Glucosylation of salicylic acid in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi-nc. Phytopathology 88, 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.I., and Raskin, I. (1999). Purification, cloning, and expression of a pathogen inducible UDP-glucose:salicylic acid glucosyltransferase from tobacco. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36637–36642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Baldauf, S., Lim, E.K., and Bowles, D.J. (2001). Phylogenetic analysis of the UDP-glycosyltransferase multigene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4338–4343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, E.K., Li, Y., Parr, A., Jackson, R.G., Ashford, D.A., and Bowles, D.J. (2001). Identification of glucosyltransferase genes involved in sinapate metabolism and lignin synthesis in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4344–4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz, F., Maury, S., Pinçon, G., and Legrand, M. (1998). cDNA cloning, substrate specificity and expression study of tobacco caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase, a lignin biosynthetic enzyme. Plant Mol. Biol. 36, 427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury, S., Geoffroy, P., and Legrand, M. (1999). Tobacco O-methyltransferases involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism: The different caffeoyl-coenzyme A/5-hydroxyferuloyl-coenzyme A 3/5-O-methyltransferase and caffeic acid/5-hydroxyferulic acid 3/5-O-methyltransferase classes have distinct substrate specificities and expression patterns. Plant Physiol. 121, 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, A., Wang, S., Neamati, M., Nicklaus, M., Sunder, S., Chen, J., Milne, G.W.A., Rice, W.G., Burke, T.R., and Pommier, Y. (1996). Antiretroviral agents as inhibitors of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and protease. J. Med. Chem. 39, 2472–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., Herr, E.H., Orvar, B.L., van Camp, W., Willekens, H., Inze, D., and Ellis, B.E. (1999). Transgenic tobacco plants with reduced capability to detoxify reactive oxygen intermediates are hyperresponsive to pathogen infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14165–14170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock, H.P., Heller, W., Molina, A., Neubohn, B., Sandermann, H., Jr., and Grimm, B. (1999). Expression of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase or coproporphyrinogen oxidase antisense RNA in tobacco induces pathogen defense responses conferring increased resistance to tobacco mosaic virus. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4231–4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, T., Nemoto, Y., and Hasezawa, S. (1992). Tobacco BY-2 cell line as the “Hela” cell in the biology of higher plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 132, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, P.J., Truesdale, M.R., Calvert, C.M., Dorans, A., Roberts, M.R., and Bowles, D.J. (1998). A novel tomato gene that rapidly responds to wound- and pathogen-related signals. Plant J. 14, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, L., Geoffroy, P., Fritig, B., and Legrand, M. (1993). Molecular cloning and expression of a new class of ortho-diphenol-O-methyltransferases induced by infection or elicitor treatment of tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 103, 509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice-Evans, C.A., Miller, N.J., and Paganga, G. (1997). Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Schopfer, P., Plachy, C., and Frahry, G. (2001). Release of reactive oxygen intermediates (superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals) and peroxidase in germinating radish seeds controlled by light, gibberellin, and abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 125, 1591–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S., Ishizuka, K., and Ohashi, Y. (1995). Induction of salicylic acid β-glucosidase in tobacco leaves by exogenous salicylic acid. Plant Cell Physiol. 36, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Shivprasad, S., Pogue, G.P., Lewandowski, D.J., Hidalgo, J., Donson, J., Grill, L.K., and Dawson, W.O. (1999). Heterologous sequences greatly affect foreign gene expression in tobacco mosaic virus-based vectors. Virology 255, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, G., Yazawa, T., Hayashida, N., and Okazaki, M. (2001). Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of novel glucosyltransferases from tobacco cultured cells that have broad substrate specificity and are induced by salicylic acid and auxin. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 4086–4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagnone, L., Merida, A., Stacey, N., Plaskitt, K., Parr, A., Chang, C.-F., Lynn, D., Dow, J.M., Roberts, K., and Martin, C. (1998). Inhibition of phenolic acid metabolism results in precocious cell death and altered cell morphology in leaves of transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Cell 10, 1801–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguy, J., and Martin, C. (1972). Phenolic compounds and the hypersensitive reaction in Nicotiana tabacum infected with tobacco mosaic virus. Phytochemistry 11, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, T., and Jones, P.R. (2000). Glycosyltransferases in plant natural product synthesis: Characterization of a supergene family. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, T., Grimm, R., and Strack, D. (1999). Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding betanidin:5-O-glucosyltransferase, a betanidine- and flavonoid-specific enzyme with high homology to inducible glucosyltransferases from the Solanaceae. Plant J. 19, 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten, R.W., Mackay, J.J., and Sederoff, R.R. (1998). Recent advances in understanding lignin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 585–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]