Abstract

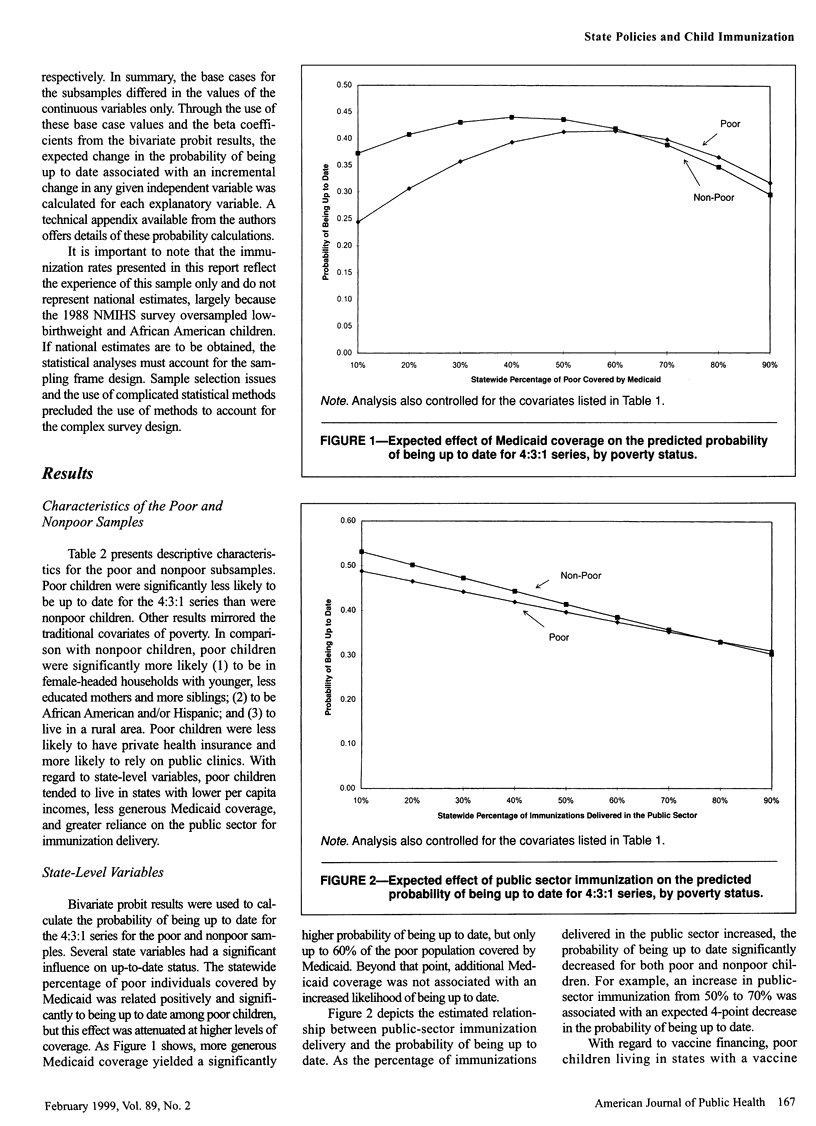

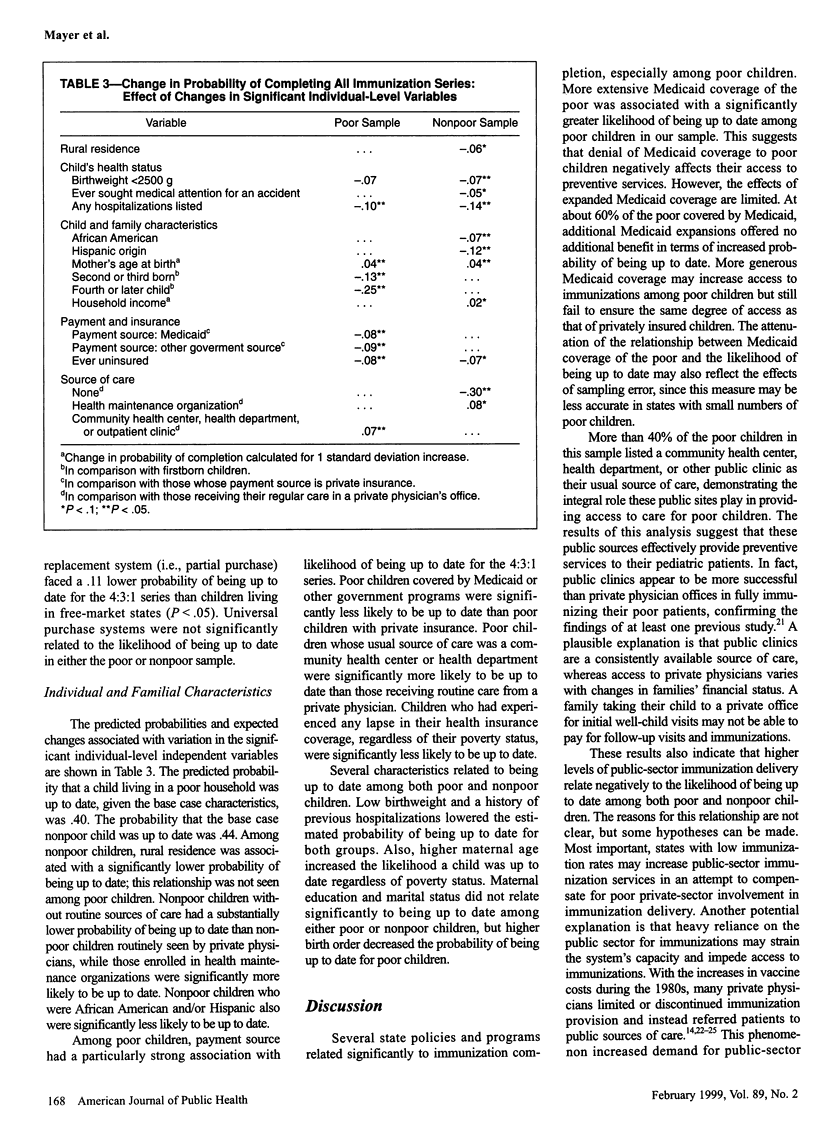

OBJECTIVES: This study assessed the influence of public policies on the immunization status of 2-year old children in the United States. METHODS: Up-to-dateness for the primary immunization series was assessed in a national sample of 8100 children from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey and its 1991 Longitudinal Follow-Up. RESULTS: Documented immunization rates of this sample were 33% for poor children and 44% for others. More widespread Medicated coverage was associated with greater likelihood of up-to-dateness among poor children. Up-to-dateness was more likely for poor children with public rather than private sources of routine pediatric care, but all children living in states where most immunizations were delivered in the public sector were less likely to be up to date. Poor children in state with partial vaccine replacement programs were less likely to be up to date than those in free-market purchase states. CONCLUSIONS: While state policies can enhance immunization delivery for poor children, heavy reliance on public sector immunization does not ensure timely receipt of vaccines. Public- and private-sector collaboration is necessary to protect children from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander C. S., Klassen A. C. Curtailment of well child services by a local health department: impact on rural 2-year-olds. Public Health Rep. 1986 May-Jun;101(3):301–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold P. J., Schlenker T. L. The impact of health care financing on childhood immunization practices. Am J Dis Child. 1992 Jun;146(6):728–732. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180088023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew G. L., Finelli L., Lutz J., DeGraaf J., Siegel B., Spitalny K. Beliefs and practices regarding childhood vaccination among urban pediatric providers in New Jersey. Pediatrics. 1995 Nov;96(5 Pt 1):889–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco W. T., Jr, Recknor J. C., Darden P. M. Who needs an immunization in a pediatric subspecialty clinic? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996 May;150(5):508–511. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170300062012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates A. S., Fitzgerald J. F., Dittus R. S., Wolinsky F. D. Risk factors for underimmunization in poor urban infants. JAMA. 1994 Oct 12;272(14):1105–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo J. K., Gale J. L., Thapa P. B., Wassilak S. G. Risk factors for delayed immunization in a random sample of 1163 children from Oregon and Washington. Pediatrics. 1993 Feb;91(2):308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordley W. C., Freed G. L., Garrett J. M., Byrd C. A., Meriwether R. Factors responsible for immunizations referrals to health departments in North Carolina. Pediatrics. 1994 Sep;94(3):376–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueston W. J., Mainous A. G., 3rd, Farrell J. B. Childhood immunization availability in primary care practices. Effects of programs providing free vaccines to physicians. Arch Fam Med. 1994 Jul;3(7):605–609. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan M. D., Alexander G. R., Teitelbaum M. A., Jack B. W., Kotelchuck M., Pappas G. The effect of gaps in health insurance on continuity of a regular source of care among preschool-aged children in the United States. JAMA. 1995 Nov 8;274(18):1429–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopreiato J. O., Ottolini M. C. Assessment of immunization compliance among children in the Department of Defense health care system. Pediatrics. 1996 Mar;97(3):308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous A. G., 3rd, Hueston W. J. Factors influencing the use of primary care physicians and public health departments for childhood immunization. J Ky Med Assoc. 1993 Sep;91(9):394–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberry P. J., Nickel J. T., Mitch R. Inadequate immunization among 2-year-old children: a profile of children at risk. J Pediatr Nurs. 1994 Jun;9(3):158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M., Placek P. J., Keppel K. G. The 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey: design, content, and data availability. Birth. 1991 Mar;18(1):26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D., Donald-Sherbourne C., Halfon N., Tucker M. B., Ortiz V., Hamlin J. S., Duan N., Mazel R. M., Grabowsky M., Brunell P. Factors related to immunization status among inner-city Latino and African-American preschoolers. Pediatrics. 1995 Aug;96(2 Pt 1):295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D., Halfon N., Sherbourne C., Grabowsky M. Access to infant immunizations for poor, inner-city families: what is the impact of managed care? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1994;5(2):112–123. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman R. K., Giebink G. S., Street H. B., Janosky J. E. Knowledge and attitudes of Minnesota primary care physicians about barriers to measles and pertussis immunization. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995 Jul-Aug;8(4):270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]