Abstract

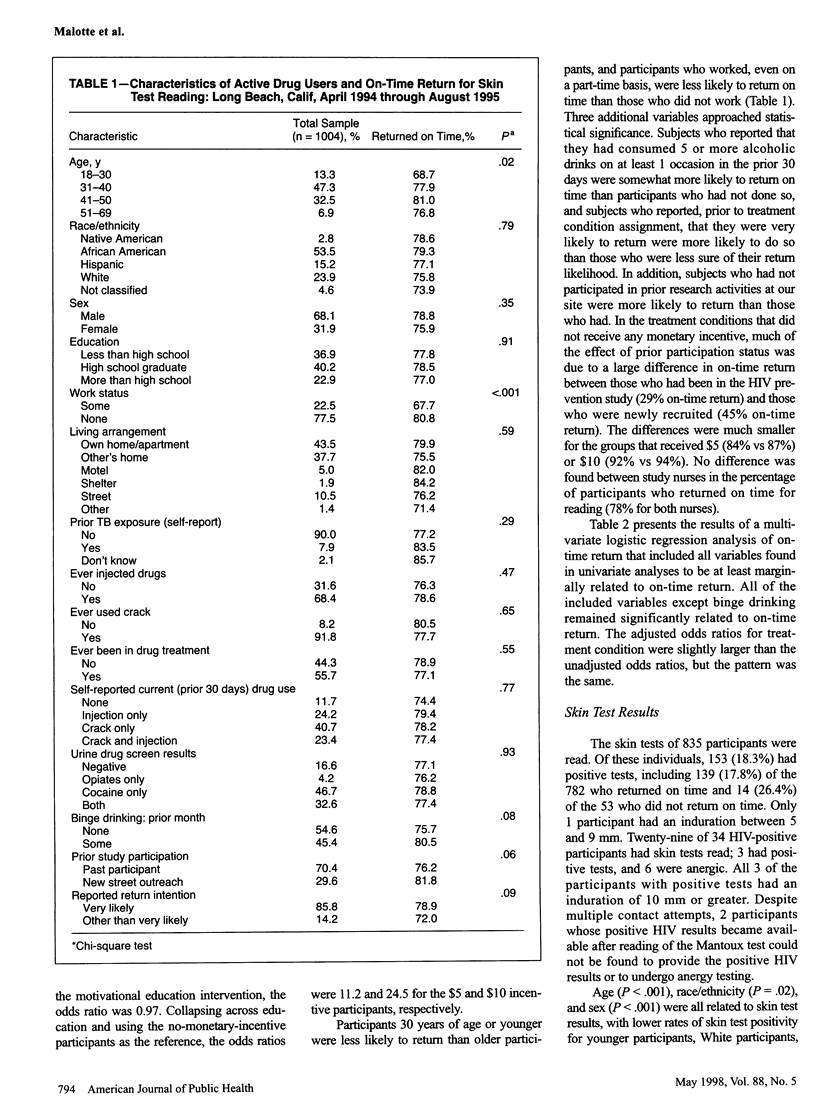

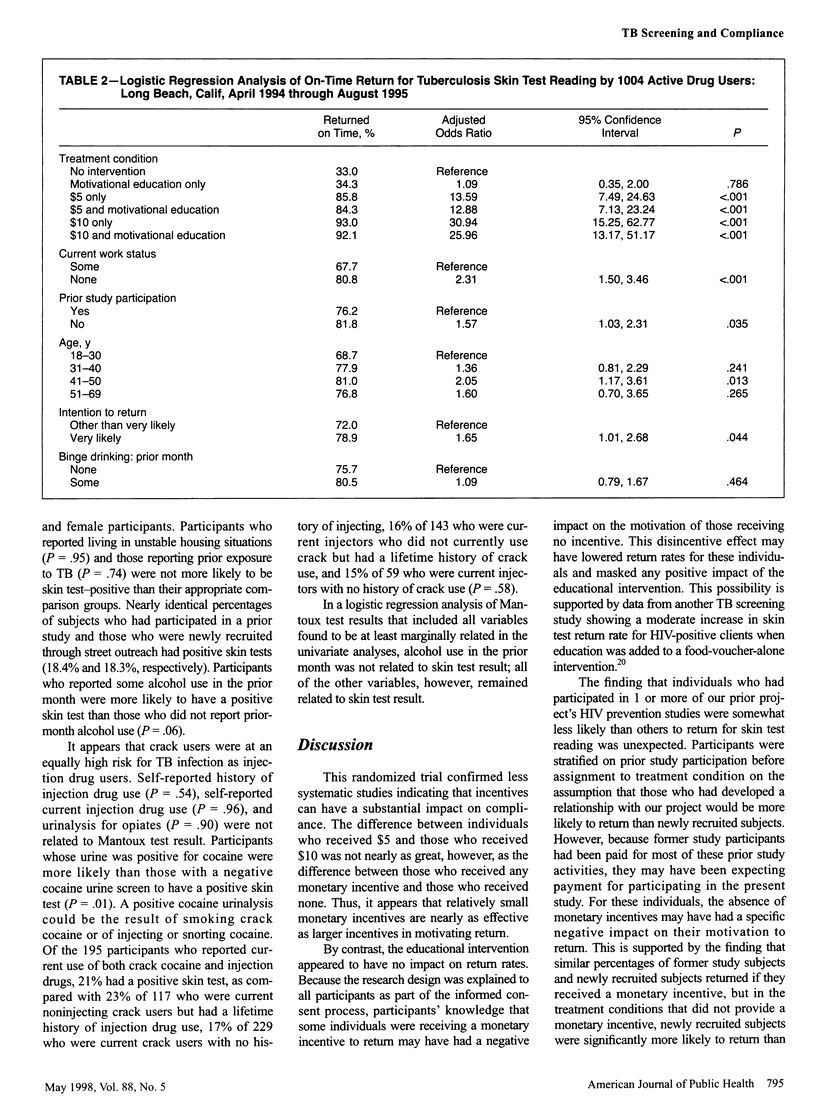

OBJECTIVES: This study assessed the independent and combined effects of different levels of monetary incentives and a theory-based educational intervention on return for tuberculosis (TB) skin test reading in a sample of active injection drug and crack cocaine users. Prevalence of TB infection in this sample was also determined. METHODS: Active or recent drug users (n = 1004), recruited via street outreach techniques, were skin tested for TB. They were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 levels of monetary incentive ($5 and $10) provided at return for skin test reading, alone or in combination with a brief motivational education session. RESULTS: More than 90% of those who received $10 returned for skin test reading, in comparison with 85% of those who received $5 and 33% of those who received no monetary incentive. The education session had no impact on return for skin test reading. The prevalence of a positive tuberculin test was 18.3%. CONCLUSIONS: Monetary incentives dramatically increase the return rate for TB skin test reading among drug users who are at high risk of TB infection.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chaisson R. E., Keruly J. C., McAvinue S., Gallant J. E., Moore R. D. Effects of an incentive and education program on return rates for PPD test reading in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996 Apr 15;11(5):455–459. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuneo W. D., Snider D. E., Jr Enhancing patient compliance with tuberculosis therapy. Clin Chest Med. 1989 Sep;10(3):375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deren S., Stephens R., Davis W. R., Feucht T. E., Tortu S. The impact of providing incentives for attendance at AIDS prevention sessions. Public Health Rep. 1994 Jul-Aug;109(4):548–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham N. M., Nelson K. E., Solomon L., Bonds M., Rizzo R. T., Scavotto J., Astemborski J., Vlahov D. Prevalence of tuberculin positivity and skin test anergy in HIV-1-seropositive and -seronegative intravenous drug users. JAMA. 1992 Jan 15;267(3):369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S. T., Budney A. J., Bickel W. K., Foerg F. E., Donham R., Badger G. J. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Jul;51(7):568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt K. K., Gentile F., Gilbert B. P., Aiken M. A cluster of tuberculosis among crack house contacts in San Mateo County, California. Am J Public Health. 1994 Nov;84(11):1834–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor R. R., Dunbar D., Graziani A. L. Tuberculin reactions among attendees at a methadone clinic: relation to infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1994 Dec;19(6):1100–1104. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D. E., Malotte C. K., Choi P., Davidson P., Rigler S., Sugland B., Langer M. A patient education program to improve adherence rates with antituberculosis drug regimens. Health Educ Q. 1990 Fall;17(3):253–267. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazar-Stewart V., Nolan C. M. Results of a directly observed intermittent isoniazid preventive therapy program in a shelter for homeless men. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Jul;146(1):57–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilote L., Tulsky J. P., Zolopa A. R., Hahn J. A., Schecter G. F., Moss A. R. Tuberculosis prophylaxis in the homeless. A trial to improve adherence to referral. Arch Intern Med. 1996 Jan 22;156(2):161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman L. B., Felton C. P., Edsall J. R. Drug dependence, a possible new risk factor for tuberculosis disease. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Mar;139(3):337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarbaro J. A. Compliance: inducements and enforcements. Chest. 1979 Dec;76(6 Suppl):750–756. doi: 10.1378/chest.76.6_supplement.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider D. E., Jr, Anders H. M., Pozsik C. J., Snijder D. E., Jr Incentives to take up health services. Lancet. 1986 Oct 4;2(8510):812–812. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo E. When tuberculosis treatment fails. A social behavioral account of patient adherence. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993 May;147(5):1311–1320. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis S. E., Slocum P. C., Blais F. X., King B., Nunn M., Matney G. B., Gomez E., Foresman B. H. The effect of directly observed therapy on the rates of drug resistance and relapse in tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994 Apr 28;330(17):1179–1184. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolopa A. R., Hahn J. A., Gorter R., Miranda J., Wlodarczyk D., Peterson J., Pilote L., Moss A. R. HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco's homeless adults. Prevalence and risk factors in a representative sample. JAMA. 1994 Aug 10;272(6):455–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]