Abstract

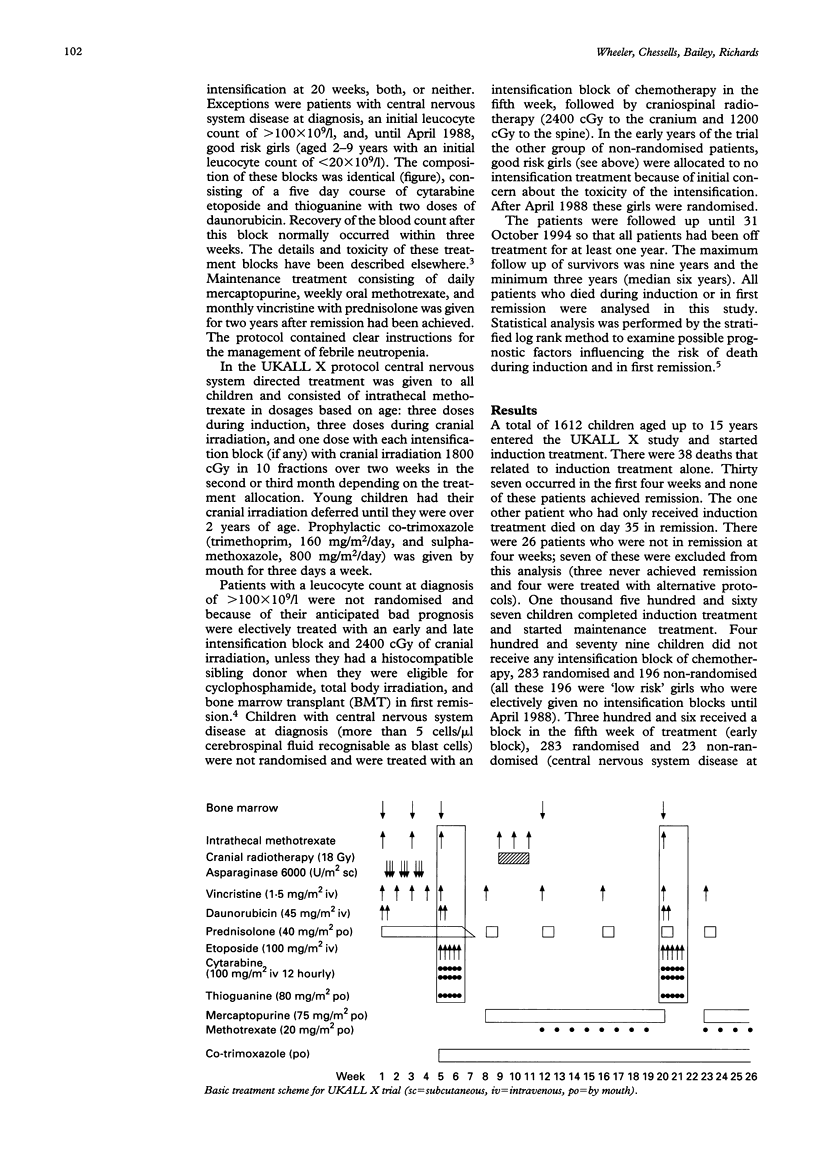

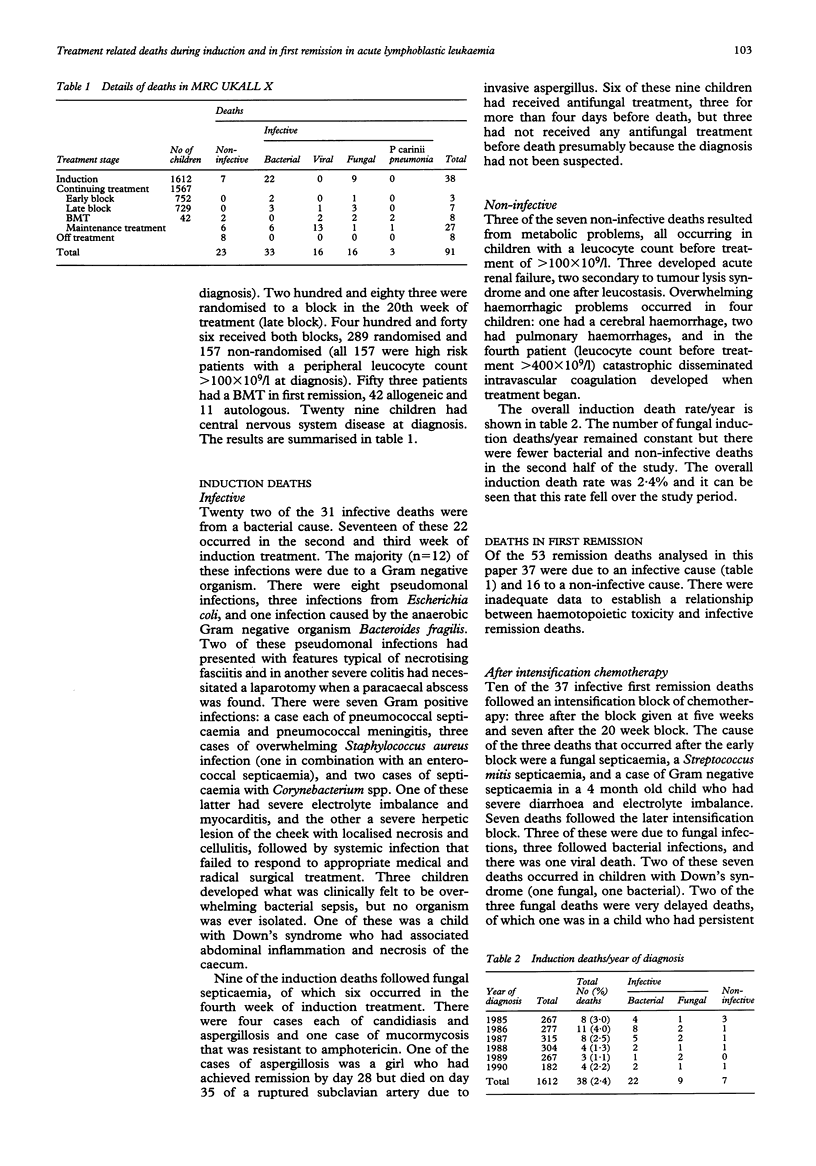

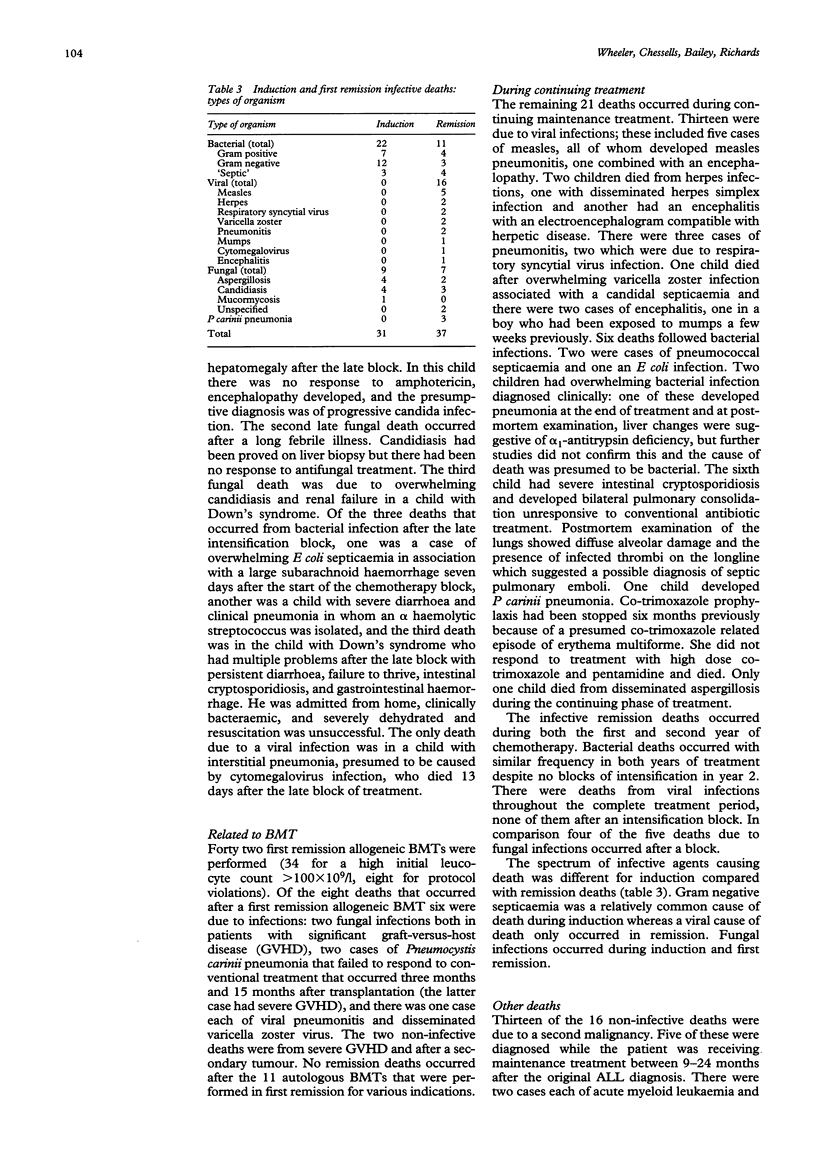

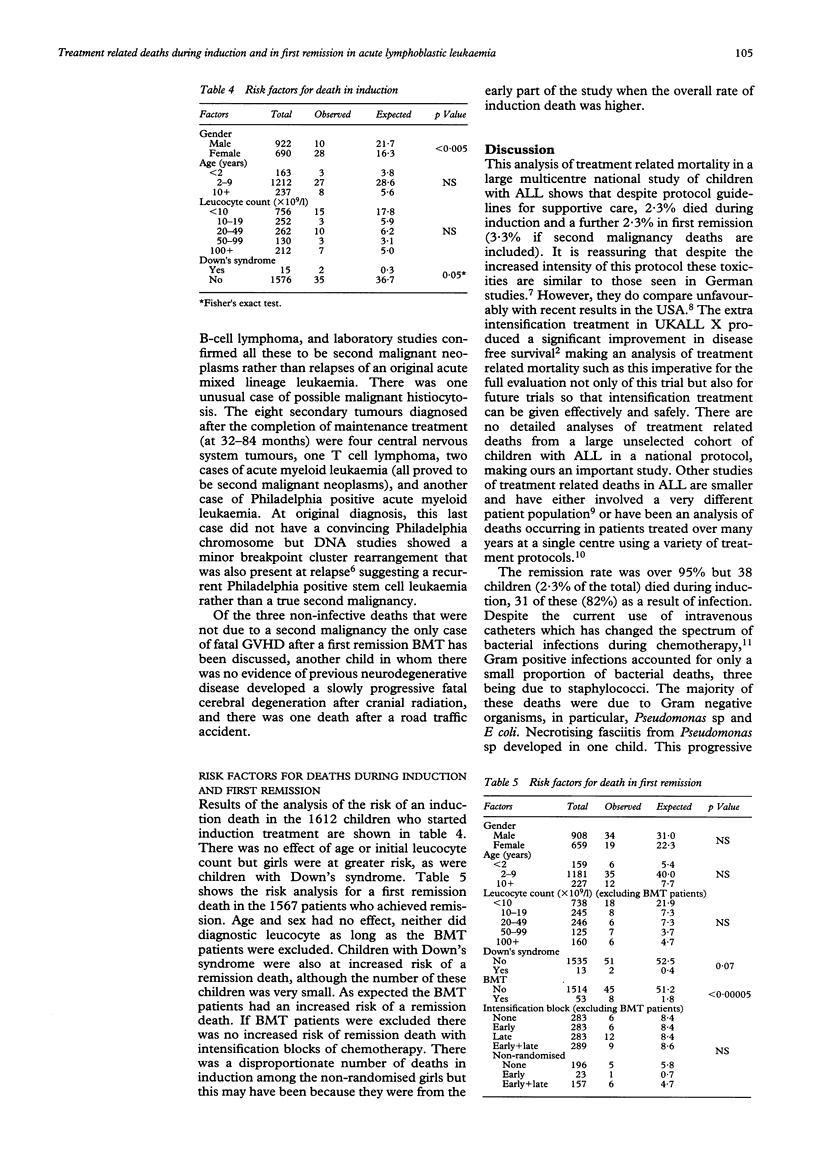

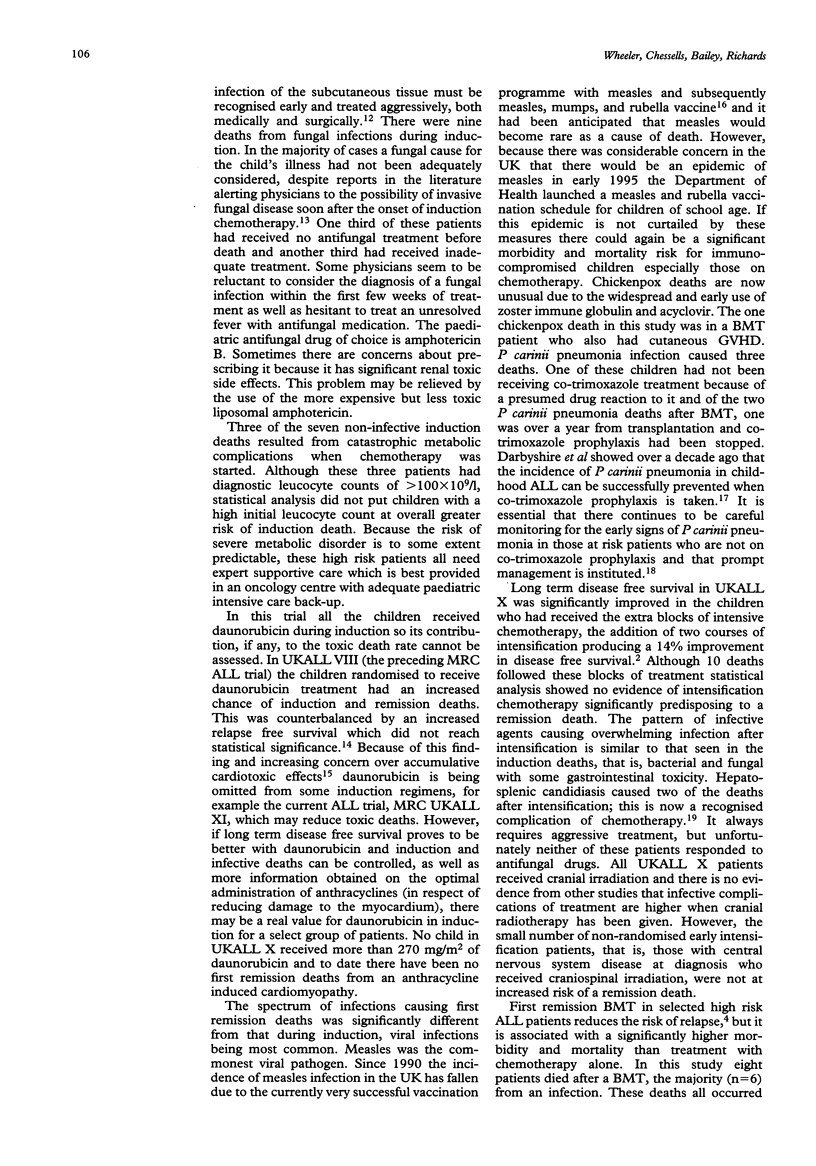

The benefits of achieving a long term event free survival of 60-70% by using increasingly intense treatment regimens must be weighed against the increased risk of treatment toxicity. From 1985 to 1990, 1612 children with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) in the UK were treated on MRC UKALL X with intensive induction therapy, central nervous system directed therapy (cranial irradiation and intrathecal methotrexate), and continuing treatment for two years. There was a randomisation to receive blocks of additional intensification treatment at five weeks, 20 weeks, not at all, or both. The five year disease free survival was 71% for children randomised to two blocks of intensification, a 14% improvement on children randomised to no intensification treatment. Treatment related mortality in this national multicentre study has been analysed for induction and first remission (including those after intensification treatment). There were 38 induction deaths, 2.3% and 53 deaths in first remission, 3.3% (including those from a second malignancy). Thirty one (84%) of the induction deaths followed an infection: bacterial in 22 and fungal in nine. Thirty seven infective remission deaths occurred: bacterial in 11, viral in 16, fungal in seven, and three caused by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Ten of these deaths followed a block of intensification treatment. The majority of noninfective remission deaths followed the development of a second tumour. Risk analysis for an induction death showed girls and children with Down's syndrome to be at greater risk. For deaths in first remission analysis showed an increased risk for bone marrow transplant (BMT) patients and children with Down's syndrome. There was no effect of age and leucocyte count for either group. Most significantly when BMT patients were excluded from the analysis, intensification treatment did not increase the risk of remission death.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Annerén G., Magnusson C. G., Lilja G., Nordvall S. L. Abnormal serum IgG subclass pattern in children with Down's syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1992 May;67(5):628–631. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.5.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atra A., Richards S. M., Chessells J. M. Remission death in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a changing pattern. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Nov;69(5):550–554. doi: 10.1136/adc.69.5.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bömelburg T., Roos N., von Lengerke H. J., Ritter J. Invasive aspergillosis complicating induction chemotherapy of childhood leukaemia. Eur J Pediatr. 1992 Jul;151(7):485–487. doi: 10.1007/BF01957749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessells J. M., Bailey C., Richards S. M. Intensification of treatment and survival in all children with lymphoblastic leukaemia: results of UK Medical Research Council trial UKALL X. Medical Research Council Working Party on Childhood Leukaemia. Lancet. 1995 Jan 21;345(8943):143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessells J. M., Bailey C., Wheeler K., Richards S. M. Bone marrow transplantation for high-risk childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia in first remission: experience in MRC UKALL X. Lancet. 1992 Sep 5;340(8819):565–568. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92103-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry V. P., Krishnamurthy L., Arya L. S., Desai N., Pati H. Causes of mortality in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Indian Pediatr. 1992 Jun;29(6):709–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden O. B., Lilleyman J. S., Richards S., Shaw M. P., Peto J. Results of Medical Research Council Childhood Leukaemia Trial UKALL VIII (report to the Medical Research Council on behalf of the Working Party on Leukaemia in Childhood). Br J Haematol. 1991 Jun;78(2):187–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb04415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haron E., Feld R., Tuffnell P., Patterson B., Hasselback R., Matlow A. Hepatic candidiasis: an increasing problem in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 1987 Jul;83(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins M. M., Draper G. J., Kingston J. E. Incidence of second primary tumours among childhood cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 1987 Sep;56(3):339–347. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson G. H., Middleton P., Prince R., Bown N., Kernahan J., Reid M. M. Philadelphia positive acute leukaemia with minor breakpoint cluster rearrangement may be a stem cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1992 May;81(1):77–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb08175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt G. A., Stiller C. A., Chessells J. M. Prognosis of Down's syndrome with acute leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1990 Feb;65(2):212–216. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J., Low C. H. Necrotising fasciitis in leukaemic children. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1990 Mar;19(2):290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur H. Prevention and treatment of pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1992 Dec 24;327(26):1853–1860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212243272606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neglia J. P., Meadows A. T., Robison L. L., Kim T. H., Newton W. A., Ruymann F. B., Sather H. N., Hammond G. D. Second neoplasms after acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991 Nov 7;325(19):1330–1336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111073251902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R., Pike M. C., Armitage P., Breslow N. E., Cox D. R., Howard S. V., Mantel N., McPherson K., Peto J., Smith P. G. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977 Jan;35(1):1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton C. R., Bowman A., Holtzel H., Chessells J. M. Intensive consolidation chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (UKALL X pilot study). Arch Dis Child. 1987 Jan;62(1):12–18. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera G. K., Pinkel D., Simone J. V., Hancock M. L., Crist W. M. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. 30 years' experience at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. N Engl J Med. 1993 Oct 28;329(18):1289–1295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310283291801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubergen D. G., Gilchrist G. S., O'Brien R. T., Coccia P. F., Sather H. N., Waskerwitz M. J., Hammond G. D. Improved outcome with delayed intensification for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and intermediate presenting features: a Childrens Cancer Group phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Mar;11(3):527–537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscoli C., Castagnola E., Rogers D. Infections in the compromised child. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1991 Apr;4(2):511–543. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]