Abstract

Reversible protein phosphorylation, which is catalyzed by functionally coupled protein kinases and protein phosphatases, is a major signaling mechanism in eukaryotic cellular functions. The red and far-red light–absorbing phytochrome photoreceptors are light-regulated Ser/Thr-specific protein kinases that regulate diverse photomorphogenic processes in plants. Here, we demonstrate that the phytochromes functionally interact with the catalytic subunit of a Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatase 2A designated FyPP. The interactions were influenced by phosphorylation status and spectral conformation of the phytochromes. Recombinant FyPP efficiently dephosphorylated oat phytochrome A in the presence of Fe2+ or Zn2+ in a spectral form–dependent manner. FyPP was expressed predominantly in floral organs. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants with overexpressed or suppressed FyPP levels exhibited delayed or accelerated flowering, respectively, indicating that FyPP modulates phytochrome-mediated light signals in the timing of flowering. Accordingly, expression patterns of the clock genes in the long-day flowering pathway were altered greatly. These results indicate that a self-regulatory phytochrome kinase-phosphatase coupling is a key signaling component in the photoperiodic control of flowering.

INTRODUCTION

Plant growth and development are not only regulated by intrinsic developmental programs but also are affected greatly by various environmental signals (Fankhauser and Chory, 1997). Light is the most critical environmental factor, and it plays two major roles in plants. Plants are photosynthetic and acquire virtually all of the biochemical energy required for survival and propagation solely from light energy. In addition, they constantly monitor the intensity, wavelength, direction, and duration of environmental light. The light signals are integrated subsequently into diverse growth and developmental processes throughout the whole life span, from seed germination to flowering, to achieve optimized growth under a given light condition (Neff et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2001). The light-regulated plant growth and developmental processes collectively are called photomorphogenesis.

Light signaling cascades that govern plant photomorphogenesis have been investigated widely by molecular biological and genetic analyses of various photomorphogenic mutants with altered light responses, mostly in Arabidopsis. A variety of light-signaling mediators, including the photoreceptors, have been identified, and their physiological roles have been elucidated in detail. A currently accepted scheme for plant photomorphogenesis suggests that light signals perceived by the photoreceptors are transmitted through a series of signaling mediators, such as phytochrome-interacting factors (Ni et al., 1998; Choi et al., 1999; Fankhauser et al., 1999), heterotrimeric G-proteins (Okamoto et al., 2001), Ras-like low molecular weight G-proteins (Kang et al., 2001), Ca2+/calmodulin (Neuhaus et al., 1993; Guo et al., 2001), and protein kinases/phosphatases (reviewed by Fankhauser and Chory, 1999), and finally regulate genes involved in photomorphogenic growth and development.

The red and far-red light–sensing phytochromes and the blue light–sensing cryptochromes are two principal photoreceptors in plant photomorphogenesis. In some cases, an individual photoreceptor is sufficient to trigger a specific light response. However, recent genetic analyses of double and triple photoreceptor mutants have shown that the photoreceptors function in a mode of finely tuned coactions (Neff and Chory, 1998; Mockler et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2001; Reeves and Coupland, 2001). The light responses mediated by the phytochromes are influenced significantly by the cryptochromes and vice versa. Moreover, physical and functional interactions between the two photoreceptors have been confirmed biochemically and genetically (Ahmad et al., 1998; Más et al., 2000; Martinez-Hernandez et al., 2002).

The phytochrome photoreceptors are light-regulated Ser/Thr-specific protein kinases (Yeh and Lagarias, 1998; Fankhauser, 2000). Although it is still a matter of some debate, two recent observations strongly support the nature of the phytochrome kinase. A prokaryotic phytochrome, Cph1, from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC6803 has structural and photochemical properties very similar to those of the eukaryotic phytochromes and exhibits light-regulated His kinase activity (Yeh and Lagarias, 1998). The kinase activity of the higher plant phytochromes also has been demonstrated in vitro using highly purified native and recombinant proteins (Yeh and Lagarias, 1998). Besides the phytochrome that is autophosphorylated (Lapko et al., 1999), additional phosphorylation substrates have been identified, including PKS1 (Fankhauser et al., 1999), Aux/IAA (Colon-Carmona et al., 2000), and the cryptochromes (Ahmad et al., 1998). Furthermore, the phytochrome-cryptochrome coactions have been confirmed functionally, especially in flowering time control (Mockler et al., 1999; Más et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2001), suggesting that protein phosphorylation plays a critical role in plant photomorphogenesis. These observations, along with the reversible protein phosphorylations that are well known in many eukaryotic kinase signaling cascades (Stone et al., 1994; Keyse, 2000), necessitate the involvement of protein phosphatases in the phytochrome kinase–mediated light signal transduction (Sheen, 1993; Chandok and Sopory, 1996; Fankhauser, 2000). However, no such protein phosphatases have been identified, and no physiological roles of protein phosphorylation have been elucidated unequivocally at the molecular level.

In this work, we used a series of molecular biological, genetic, and biochemical approaches to demonstrate that reversible protein phosphorylation is a key component of phytochrome-mediated light signal transduction. A Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatase 2A (designated FyPP for flower- specific, phytochrome-associated protein phosphatase) associates with and dephosphorylates the phytochromes in a light wavelength–dependent manner. Arabidopsis plants with reduced FyPP levels exhibited early flowering, whereas those with increased FyPP levels flowered later than control plants. The expression patterns of the circadian clock genes were altered accordingly. In agreement with these findings, the FyPP gene was expressed predominantly in floral organs and influenced significantly by daylength. These results indicate that phytochrome-mediated light signals are further modulated by protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in flowering time control, providing direct molecular evidence for the function of protein phosphorylation in phytochrome kinase signaling.

RESULTS

Phytochromes Associate with a Protein Phosphatase 2A

To search for the protein phosphatase that interacts specifically with the phytochrome kinases, we conducted yeast two-hybrid screens using the C-terminal half (residues 667 to 1122) of the Arabidopsis phytochrome A as bait. We first screened cDNA libraries constructed from Arabidopsis plants but failed to isolate a gene encoding such a phytochrome-interacting protein phosphatase, possibly because its transcript is rare, if it exists, in the mRNA pools used to construct the cDNA libraries. As an alternative, we chose a cDNA library constructed from dark-grown pea seedlings (Kang et al., 2001).

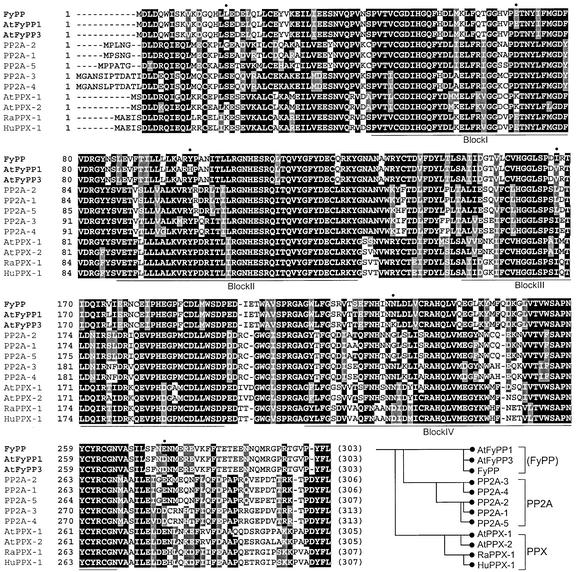

Sequence analysis of the positive cDNA clones (his3+ and lacZ+) identified a group of cDNA clones that contained an uninterrupted open reading frame encoding the catalytic subunit of a Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). The deduced polypeptide consists of 303 residues with an estimated molecular mass of 34.7 kD (Figure 1). It contains all of the structural elements (blocks I to IV) highly conserved among PP2A family members (Virshup, 2000). However, it is somewhat different from other PP2A members, such as PP2A and PPX subfamily members, as indicated by relative sequence similarities, and apparently it belongs to a distinct subfamily. The phytochrome-associated PP2A was designated FyPP.

Figure 1.

Multiple Sequence Alignment of FyPP and Related PP2A Members.

Four protein blocks highly conserved among the PP2A members are underlined (blocks I to IV). Amino acid residues that differ among FyPP, AtFyPP1, and AtFyPP3 are indicated by dots above the FyPP sequence. A phylogenetic tree, showing the interrelationships among the PP2A members, is displayed at bottom right. The PP2A members aligned are Arabidopsis PP2A-1 to PP2A-5, Arabidopsis PPX-1 and PPX-2, human and rat PPX-1s (RaPPX-1 and HuPPX-1), AtFyPP1, AtFyPP3, and FyPP. The sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL W version 1.7 (Thompson et al., 1994).

A putative FyPP gene ortholog also was isolated from Arabidopsis by reverse transcription (RT)–PCR amplification using degenerate primers and poly(A) mRNA (AtFyPP3; Figure 1). It was located on chromosome 3 by sequence comparison with the Arabidopsis genome sequence. Interestingly, further database searches identified one additional Arabidopsis gene on chromosome 1 encoding a polypeptide (designated AtFyPP1) with a sequence identity of >98% to FyPP and AtFyPP3, even with most of the substitutions conserved biochemically among the three FyPP members, such as E69D, I167V, and S219T. The two Arabidopsis polypeptides differ only at two residues, Glu or Asp at position 70 and His or Tyr at position 100 in AtFyPP1 and AtFyPP3, respectively (Figure 1), suggesting that they are FyPP orthologs in Arabidopsis.

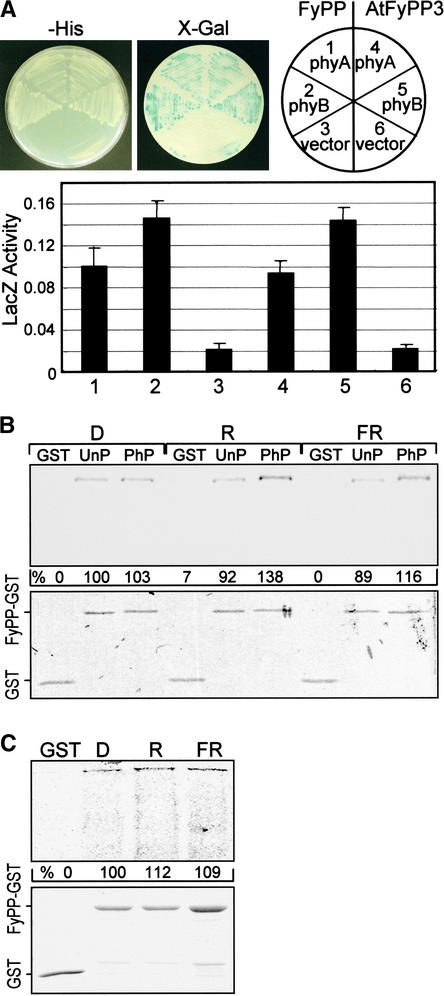

The phytochrome–FyPP interaction was examined further by yeast coexpression (Figure 2A) and by in vitro pulldown assays using a recombinant FyPP–glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein and purified native oat phytochrome A (Figure 2B) or recombinant Arabidopsis phytochrome B (Figure 2C). Phytochrome B was expressed in Escherichia coli cells and reconstituted in vitro with phycocyanobilin for the assays. AtFyPP3 also was included in the assays to examine the molecular equivalence between FyPP and AtFyPPs. FyPP associated with both phytochromes A and B, but it associated 1.4 times more efficiently with the latter (Figure 2A). AtFyPP3 also associated with the phytochromes in patterns identical to that of FyPP. For in vitro pulldown assays, a FyPP-GST fusion protein, in which the GST was fused to the C terminus of the full-size FyPP, was generated and purified in E. coli cells. The FyPP-GST fusion protein efficiently bound oat phytochrome A (Figure 2B) and phytochrome B (Figure 2C). The AtFyPP3-GST fusion protein also showed identical results (data not shown). Therefore, it is evident that FyPP and its putative Arabidopsis orthologs (AtFyPPs) bind both phytochromes A and B, but with an obvious preference for the latter.

Figure 2.

Interactions of FyPP and AtFyPP3 with Phytochromes A and B.

The interactions were examined by yeast coexpression and in vitro pulldown assays.

(A) Yeast coexpression.

(B) Phytochrome A–FyPP interactions. The phytochromes prepared in the dark (D) were treated with either red (R) or far-red (FR) light before use. Bound phytochromes were detected immunologically using a polyclonal anti-phyA antibody. Binding activities were expressed relative to that (100%) of the unphosphorylated phytochrome A in the dark. PhP and UnP, phosphorylated and unphosphorylated oat phytochrome A, respectively.

(C) Phytochrome B–FyPP interactions. A full-size recombinant Arabidopsis phytochrome B from E. coli was reconstituted in vitro with PCB. In vitro pulldown assays were performed as described in (B).

The bottom panels in (B) and (C) show Coomassie brilliant blue–stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

We then examined whether the phytochrome–FyPP interaction was affected by the spectral conformation and phosphorylation status of the phytochromes. FyPP bound the Pfr phytochrome ∼30% more efficiently than the Pr form. Phytochrome phosphorylation status also influenced the interactions. FyPP associated more efficiently with the phosphorylated phytochromes than with the unphosphorylated forms. Phytochrome B also bound FyPP in similar patterns (Figure 2C). These observations indicate that the phytochrome–FyPP interaction is modulated by light wavelength, signifying a role for FyPP in phytochrome-mediated light signaling.

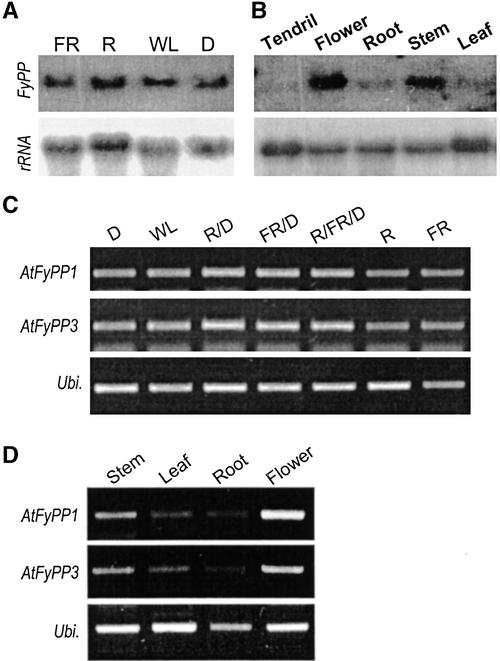

FyPP Is Localized in the Cytoplasm in Floral Organs

The interactions of FyPP with the phytochromes suggested that FyPP gene expression would be regulated by light wavelength. However, RNA gel blot hybridization analysis showed that it was not affected notably by light (Figure 3A). It was expressed to an equal level in all light conditions tested, indicating that the phytochrome–FyPP interaction is regulated by light primarily via the Pr↔Pfr phototransformation of the phytochromes. To obtain clues regarding FyPP's function, FyPP gene expression was examined in different plant organs. It was expressed predominantly in flowers and flowering stems, but the transcript level was relatively very low in other organs (Figure 3B), suggesting a flowering-specific role for FyPP. AtFyPP genes also exhibited identical light-independent (Figure 3C) but floral organ–specific (Figure 3D) expression patterns, supporting the notion that they are FyPP gene orthologs in Arabidopsis. As anticipated from the yeast two-hybrid screens (see above), AtFyPP transcript levels were very low compared with those of FyPP, and they were detected by RT-PCR but not by ordinary RNA gel blot analysis. This distinction may reflect a physiological difference between pea, a short-day plant, and Arabidopsis, a long-day plant.

Figure 3.

Expression Patterns of the FyPP and AtFyPP Genes.

(A) Light effects on FyPP gene expression. Pea plants were grown in far-red light (FR), red light (R), white light (WL), or in the dark (D).

(B) Organ-specific expression of the FyPP gene.

18S rRNA (18S) was probed with 32P-labeled rDNA as a control for constitutive expression in (A) and (B).

(C) AtFyPP gene expression under various light wavelengths.

(D) Organ-specific expression of the AtFyPP genes.

An Arabidopsis ubiquitin gene (Ubi.) was used as a control for constitutive expression in (C) and (D).

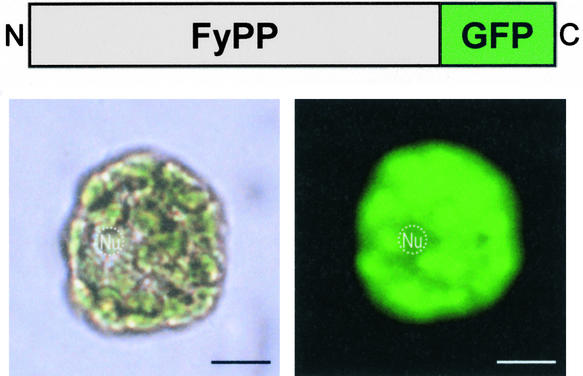

Another clue to FyPP's function was provided by its subcellular localization. Nucleocytoplasmic translocation of the phytochromes is a critical step in phytochrome function. Phytochromes A and B are localized in the cytoplasm under far-red light but translocated into the nucleus under red light (Kircher et al., 1999; Nagy et al., 2000). To examine the subcellular localization of FyPP in plant cells, a green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequence was fused in frame to the 3′ end of the FyPP gene. The FyPP-GFP fusion protein was expressed transiently in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Bright-field and fluorescence microscopy images revealed that FyPP is localized constitutively in the cytoplasm, unlike the phytochromes (Figure 4). The GFP-FyPP fusion protein, in which the GFP was fused to the N terminus of the full-size FyPP, and the FyPP-GUS fusion protein also were localized exclusively in the cytoplasm of onion epidermal cells when expressed transiently (data not shown). These observations indicate that FyPP regulates phytochrome phosphorylation in the cytoplasm, which may be important for the nuclear translocation and/or cytoplasmic function of the phytochromes.

Figure 4.

Subcellular Localization of FyPP.

Bright-field (bottom left) and fluorescent (bottom right) images of Arabidopsis protoplasts expressing the FyPP-GFP fusion protein (top) are shown. Nuclei (Nu) are indicated. Bars = 10 μm.

Additionally, we observed that the FyPP-GFP and FyPP-GUS fusion proteins were unusually unstable. The fusions were visible for only a short time (<1 h) at 7 to 8 h after particle bombardment, and the fluorescent images disappeared completely after that. These findings suggest that FyPP could become stable as it binds the phytochromes or that the phytochrome–FyPP interaction is a subtle step during phytochrome signaling.

Phytochrome Dephosphorylation by FyPP Is Regulated by Light Wavelength

Oat phytochrome A is autophosphorylated at distinct Ser residues, such as Ser-7, Ser-17, and Ser-598, by the intrinsic kinase activity (Yeh and Lagarias, 1998; Lapko et al., 1999). FyPP is a PP2A that interacts directly with the phytochromes (Figures 1 and 2). We tried to determine whether FyPP dephosphorylates the phytochromes. We also reasoned that phytochrome dephosphorylation by FyPP would be modulated by light wavelength if the phytochrome–FyPP interaction is functionally important. 32P-labeled oat phytochrome A was used as a dephosphorylation substrate. FyPP activity was examined using a recombinant FyPP expressed in E. coli cells. Various cations also were included in the assays because PP2A members require diverse cations for full enzymatic activities.

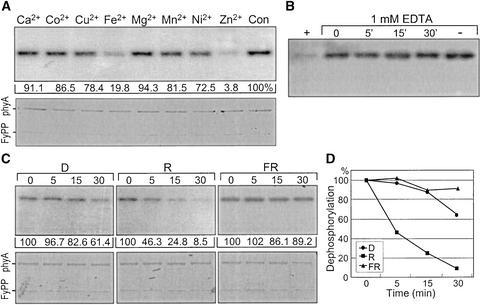

FyPP efficiently dephosphorylated the phosphorylated oat phytochrome A, but only in the presence of Fe2+ or Zn2+ (Figure 5A). Zn2+ was more catalytic than Fe2+ on FyPP activity. By contrast, other cations showed only marginal effects. These results indicate that FyPP is biochemically unique among PP2A family members (Virshup, 2000), which also is consistent with the sequence diversities observed among PP2A members (Figure 1). A divalent cation chelator, EDTA, abolished the dephosphorylation reactions completely, confirming the absolute cation requirement for FyPP activity (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Protein Phosphatase Activity of FyPP.

32P-labeled oat phytochrome A was used as a substrate. Dephosphorylation reactions were performed in the dark (D), in red light (R), or in far-red light (FR).

(A) Divalent cation requirements. Dephosphorylation rates are displayed as the radioactivity remaining after dephosphorylation reactions relative to that (100%) of a control reaction without cation (Con).

(B) EDTA effect. One millimolar EDTA was included as indicated. +, a control reaction without EDTA but with FyPP; −, a control reaction without FyPP but with EDTA.

(C) Spectral form dependence. One millimolar Zn2+ was included in all reactions. The bottom panels show Coomassie brilliant blue–stained SDS polyacrylamide gels.

(D) Time course of the dephosphorylation reactions.

We then tried to determine whether FyPP differentially dephosphorylated the Pfr and Pr phytochromes. The Pfr phytochrome was dephosphorylated more readily than the Pr form by FyPP (Figures 5C and 5D). These findings are related to the facts that the Pfr phytochrome is a physiologically active form in most photomorphogenic responses (Roux, 1994) and that phosphorylation status is important for phytochrome function (Fankhauser, 2000). AtFyPPs also exhibited the same enzymatic activity and cation requirement as FyPP (data not shown). The oat phytochrome A and FyPP proteins themselves were unaffected under the assay conditions used (Figures 6A and 6B, bar graphs at bottom).

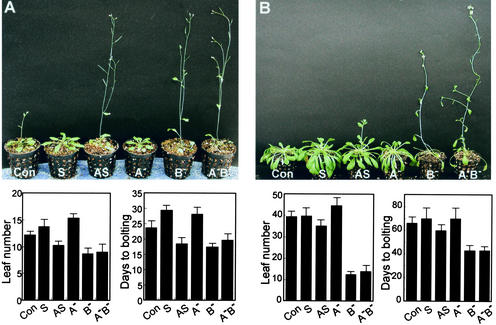

Figure 6.

FyPP Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants.

Transgenic plants were grown in either long days (16 h of light/8 h of dark) or short days (8 h of light/16 h of dark).

(A) Transgenic plants grown in long days.

(B) Transgenic plants grown in short days.

The number of rosette leaves was counted at the day of bolting. Days to bolting refers to the days between the date when plants were put in the light and the date of bolting. Twenty plants were measured for each plant shown. Con, control; S and AS, sense and antisense FyPP transgenic plants, respectively; A−, phytochrome A null mutant; B−, phytochrome B null mutant; A−B−, phytochrome A and B double mutant.

FyPP Modulates Phytochrome Signals in Flowering Time Control

To explore the physiological role of the phytochrome–FyPP interaction, a full-size FyPP gene was introduced into Arabidopsis plants in both the sense and antisense orientations, and homozygotic transgenic lines were obtained. FyPP transgenic plants did not show any discernible phenotypic alterations during the seed germination and seedling growth stages. However, adult plants exhibited a marked phenotypic change. Sense transgenic plants displayed delayed flowering, whereas antisense transgenic plants flowered earlier than control plants in long days (Figure 6A). By contrast, in short days, antisense transgenic plants flowered slightly earlier than control plants, but sense transgenic plants were not noticeably different (Figure 6B). These results demonstrate that FyPP plays a major role in the photoperiodic control of flowering time in long days. The specific role of FyPP in flowering time control also is consistent with its predominant expression in floral organs (Figure 3). FyPP transgenic plants did not show any variations in plant morphology and flower architecture other than altered flowering times, indicating that the primary role of FyPP is to control flowering initiation and that it is not involved directly in other growth and developmental processes.

Interestingly, the delayed flowering phenotype of sense transgenic plants was very similar to that of the phytochrome A null mutant (phyA), whereas the accelerated flowering phenotype of antisense transgenic plants was similar to that of the phytochrome B null mutant (phyB) (Bagnall et al., 1995) (Figure 6). These phenotypic similarities indicate that FyPP functions directly on the phytochromes by dephosphorylating certain Ser residues and acts as a negative regulator in the photoperiodic control of flowering. In agreement with this finding, the cryptochromes, which are phosphorylated by the phytochrome kinases, were not the dephosphorylation substrate for FyPP, and no interactions were detected between them in yeast coexpression assays (data not shown).

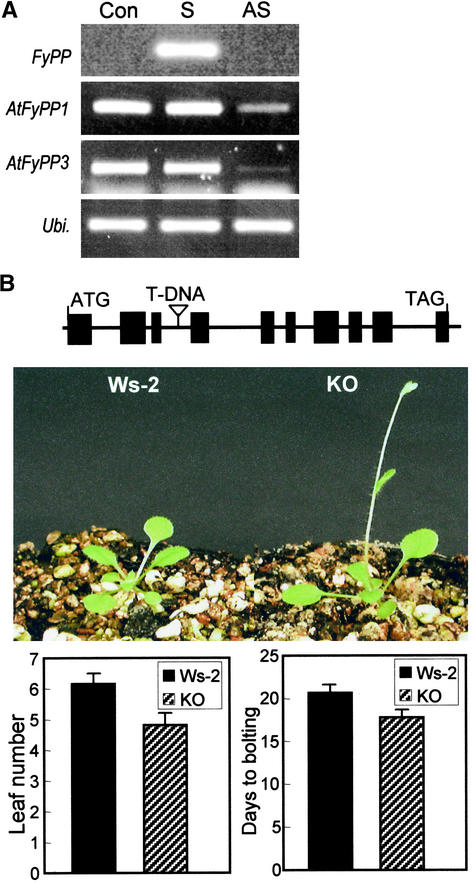

The high amino acid sequence homology (98%) with FyPP (Figure 1), the specific interactions with the phytochromes in a manner similar to that of FyPP (Figure 2), and the similar expression profiles (Figure 3) all strongly supported the idea that AtFyPPs are structurally and functionally homologous with FyPP. To further examine this possibility, the expression patterns of the FyPP transgene and intrinsic AtFyPP genes were analyzed in FyPP transgenic plants. RT-PCR, rather than RNA gel blot analysis, was used to distinguish their expression, because the two AtFyPP gene sequences share 92% identity. PCR primers were designed based on the sequence regions that are most divergent between the two gene sequences, and the expected sizes of the PCR products also were different from each other: 529 bp for AtFyPP1 and 448 bp for AtFyPP3. In antisense transgenic plants that showed early flowering, the two Arabidopsis genes as well as the FyPP antisense transgene were suppressed drastically (Figure 7A). By contrast, expression of the intrinsic AtFyPP genes was unaffected in sense transgenic plants. Together with the observation that AtFyPP genes are expressed predominantly in floral organs, like FyPP (Figure 3D), this result indicates that AtFyPPs are functionally equivalent to FyPP.

Figure 7.

Functional Equivalence between FyPP and AtFyPPs.

(A) AtFyPP gene expression in FyPP transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Con, control; S and AS, sense and antisense FyPP transgenic plants, respectively; Ubi., an Arabidopsis ubiquitin gene.

(B) Phenotype of an AtFyPP3-deficient Arabidopsis knockout plant compared with a wild-type plant. A T-DNA was inserted into the third intron of the AtFyPP3 gene. Plants were grown in long days. Seventy plants of each line were used for each statistical measurement. Number of rosette leaves and days to bolting were as described for Figure 6. KO, knockout plant; Ws-2, wild-type plant (Wassilewskija-2).

To demonstrate unequivocally the functional equivalence, an AtFyPP3-deficient Arabidopsis mutant was isolated from a T-DNA insertion pool (ecotype Wassilewskija-2). DNA sequencing revealed that a T-DNA was inserted in the third intron of the AtFyPP3 gene (Figure 7B, top). The absence of AtFyPP3 gene expression in the knockout mutant was verified by RT-PCR (data not shown). The knockout mutant also exhibited an accelerated flowering phenotype (Figure 7B). However, it was not as prominent as that observed in antisense FyPP transgenic plants (Figure 6), possibly because the parental ecotype used to generate the T-DNA insertion pool was Wassilewskija-2, an early-flowering ecotype. Therefore, we conclude that FyPP and its functional orthologs, the AtFyPPs, play a common role in flowering time control.

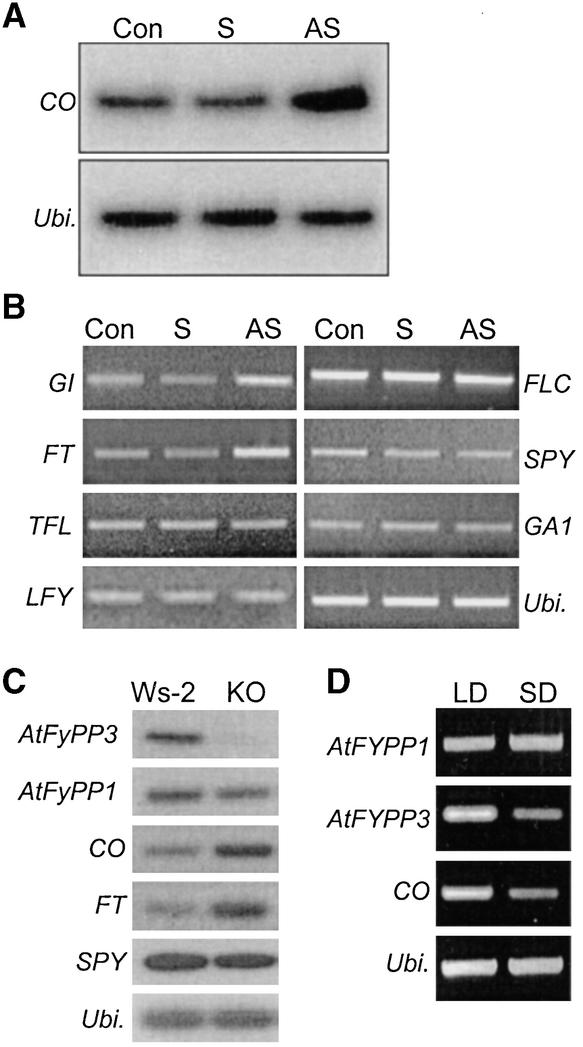

FyPP Functions Primarily through the Long-Day Flowering Pathway

Flowering in Arabidopsis, a facultative long-day plant, is regulated through a complex network of multiple genetic pathways that respond to a wide range of environmental and intrinsic developmental cues (Koornneef et al., 1998; Piñeiro and Coupland, 1998; Blázquez et al., 2001; Simpson and Dean, 2002). The long-day pathway promotes flowering initiation in long days, in which a group of clock genes are involved. The gibberellic acid (GA) pathway is absolutely required for floral induction under noninductive short-day conditions, although the molecular nature of the input signal is unknown. Temperature and plant age and growth status also influence flowering.

CONSTANS (CO) gene expression is regulated by the circadian clock with a peak between 12 h after dawn and subsequent dawn (Suárez-López et al., 2001). It also is regulated by daylength (Koornneef et al., 1998). It is relatively high when Arabidopsis plants are grown in long days but relatively low in short days. Our results indicated that FyPP and AtFyPPs regulate phytochrome-mediated light signals in flowering time control, mainly in long days (Figure 6A). Therefore, it was expected that CO expression, which accelerates flowering initiation exclusively in long days, would be altered in FyPP transgenic plants. To examine this possibility, wild-type and FyPP transgenic plants were grown for 3 weeks in long days, and plant materials were harvested 6 h after dawn. Quantitative RT-PCR/DNA gel blot analysis revealed that the CO transcript level decreased to half of the wild-type level in sense transgenic plants, whereas it increased ∼2.5-fold in antisense transgenic plants (Figure 8A). These observations support the notion that FyPP regulates phytochrome-mediated light signals in the long-day flowering pathway.

Figure 8.

Flowering Time Gene Expression in FyPP Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants.

(A) CO gene expression. Plants were grown for 3 weeks in long days, and total RNAs were isolated from whole plants at 6 h after dawn. The CO transcript level was quantitated by RT-PCR/DNA gel blot analysis.

(B) Flowering time gene expression in FyPP transgenic plants.

(C) Flowering time gene expression in the AtFyPP3-deficient mutant.

(D) Daylength effects on AtFyPP gene expression. Arabidopsis plants were grown in either long days or short days.

Con, control plant; KO, knockout plant; LD and SD, long days and short days, respectively; S and AS, sense and antisense FyPP transgenic plants, respectively; Ubi., an Arabidopsis ubiquitin gene; Ws-2, wild-type plant (Wassilewskija-2).

In addition to altered CO gene expression (Figure 8A), those of other flowering time genes also were influenced (Figure 8B). The transcript levels of the GIGANTEA and FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) genes increased approximately threefold in antisense transgenic plants but decreased to a detectable level in sense transgenic plants. This finding also is consistent with their roles in flowering (Weigel et al., 1992; Bradley et al., 1997; Blázquez and Weigel, 2000).

Recent molecular genetic studies have shown that multiple input signals are integrated via the so-called floral pathway integrators, such as LEAFY (LFY), FT, and AGL20, that are regulated by GA as well as by light (Kobayashi et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2000; Samach et al., 2000). This entails possible cross-talk between light and GA signals in flowering time control, although direct molecular evidence is unavailable at present.

To determine whether GA or other factors are related to the light signals mediated by the phytochrome–FyPP interaction, the expression of the GA1 and SPY genes involved in GA biosynthesis and signaling (Blázquez, 2000; Simpson and Dean, 2002) was analyzed in FyPP transgenic plants. The transcript levels were not significantly different from those in wild-type plants (Figure 8B), indicating that the GA pathway is not under the direct control of FyPP. The transcript levels of the FLOWERING LOCUS C, TERMINAL FLOWER (TFL), and LFY genes also were unaltered in FyPP transgenic plants (Figure 8B). Therefore, it is clear that FyPP plays its role through the long-day flowering pathway. To examine this notion further, the AtFyPP3-deficient plant (Figure 7B) was analyzed in a similar manner. The transcript levels of the CO and FT genes increased significantly, whereas that of the SPY gene did not (Figure 8C), confirming the primary role of FyPP in the long-day flowering pathway.

We then examined whether AtFyPP gene expression was regulated by daylength, as observed with CO gene expression. Interestingly, AtFyPP3 was expressed at a higher level in long days than in short days, like CO, whereas AtFyPP1 did not exhibit such differential expression (Figure 8D). These observations suggest that although AtFyPPs are biochemically equivalent, they play distinct roles in flowering time control. AtFyPP1 may be functional in both long-day and short-day conditions, but AtFyPP3 is required for phytochrome-mediated light signaling specifically in long days.

In conclusion, it is evident that a phytochrome kinase–associated PP2A modulates light signals in the photoperiodic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. The phytochrome–FyPP interaction is specific to the long-day flowering pathway but is not related directly to other genetic pathways in flowering time control. It also is clear that protein phosphorylation is a key molecular event in phytochrome kinase–mediated light signaling in plants, as demonstrated in various eukaryotic kinase signaling pathways.

DISCUSSION

Phytochrome Kinases Interact Functionally with a PP2A

Reversible protein phosphorylation is a feedback-control mechanism in various eukaryotic kinase signaling cascades (Stone et al., 1994; Westphal et al., 1998; Keyse, 2000). Recent molecular biological and biochemical evidence indicates that coordinated interactions between coupled protein kinases and phosphatases also play important roles in plants, especially in cell cycle control, in which a set of cyclin-dependent kinases and protein phosphatases are involved (Meszaros et al., 2000; Boniotti and Griffith, 2002). It also has been suggested that protein phosphorylation is an essential step in light signal transduction in plants and that protein phosphatase(s) possibly is involved in this process (Sheen, 1993; Harter et al., 1994; Chandok and Sopory, 1996; Fankhauser, 2000).

The eukaryotic phytochromes are unique red/far-red light receptors in that they perceive environmental light through the N-terminal chromophore binding domain and exert regulatory roles through the C-terminal domain. The C-terminal domain possesses structural elements required for interactions with downstream signaling mediators (Ni et al., 1998; Choi et al., 1999; Fankhauser et al., 1999). It also contains a motif that is similar to the prokaryotic His kinases. It is now generally accepted that the phytochromes are Ser/Thr-specific protein kinases that are regulated by light (Fankhauser and Chory, 1999). Furthermore, phytochrome autophosphorylation at certain Ser residues and phosphorylation of the phytochrome kinase substrates are essential for phytochrome function (Harter et al., 1994; Roux, 1994; Chandok and Sopory, 1996; reviewed by Nagy et al., 2000). Because the phytochromes are molecular light switches that regulate many photomorphogenic growth and developmental processes, biochemical and physiological activities should be controlled precisely. One potential molecular means to achieve this would be to modulate the phosphorylation status of the phytochromes, which requires that the intrinsic phytochrome kinase activity be coupled with a protein phosphatase(s). The recent identification of the phytochrome kinase substrates further supports this view.

Cryptochrome phosphorylation by the phytochrome kinases is regulated by light wavelength and required for the photoactivation of blue light responses (Ahmad et al., 1998). Notably, the photoactivated cryptochromes downregulate COP1 activity via direct protein–protein interactions in blue light–mediated photomorphogenic responses (Wang et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Therefore, it is assumed that modulation of the phytochrome function by reversible phosphorylation is an essential event that influences diverse plant growth and developmental processes.

Our experimental data demonstrate that FyPP and its functional orthologs in Arabidopsis, the AtFyPPs, are protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate the phytochrome kinases, providing molecular evidence for the presence of functional phytochrome kinase–phosphatase coupling in light signal transduction in plants. The phytochrome–FyPP interaction is influenced by the spectral conformation and phosphorylation status of the phytochromes. FyPP binds both phytochromes A and B, but with a relatively higher affinity for the latter (Figure 2). Transgenic plants with overexpressed or suppressed FyPP levels exhibit delayed- or early-flowering phenotypes (Figure 6) that mimic those observed in the phyA or phyB null mutant, respectively. All of these observations suggest that FyPP modulates both phytochrome A and B signals in flowering time control. However, it seems that FyPP has an opposite effect in each signaling pathway, a negative regulatory role in the former and a positive regulatory role in the latter. This finding may be related to the antagonistic roles played by phytochromes A and B in flowering time control (Mockler et al., 1999), although the exact molecular mechanisms remain to be examined. Genetic crosses between photoreceptor mutants and FyPP transgenic or knockout plants would clarify this point.

It is unlikely that FyPP is the only protein phosphatase that interacts directly with the phytochromes. Because the phytochromes regulate various aspects of plant photomorphogenesis, it is highly possible that more than one protein phosphatase would be involved, each for a specific photomorphogenic process. It will be interesting to determine whether multiple protein phosphatases interact with the same structural motif or with distinct motifs in the phytochrome molecule. This hypothesis reflects the fact that multiple phytochrome-interacting factors with apparently distinct roles interact with the phytochromes.

Reversible Protein Phosphorylation Is a Primary Switch That Initiates Phytochrome Signaling

Phytochromes are autophosphorylated at distinct Ser residues, such as Ser-7, Ser-17, and Ser-598 (Lapko et al., 1999). Phosphorylation at these residues induces subtle conformational changes in the phytochrome molecule, which affect its interactions with downstream signaling mediators. Additionally, analysis of a S598A mutant phytochrome A revealed that phosphorylation at Ser-598 is critical for light regulation of phytochrome autophosphorylation and kinase activity (Fankhauser et al., 1999). Ser-598 is phosphorylated selectively in the Pfr phytochrome. Although it remains to be determined whether Ser-598 is the site dephosphorylated by FyPP or its orthologs, these observations strongly suggest that protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is an early biochemical event that initiates phytochrome signaling in conjunction with Pr↔Pfr phototransformation.

How does FyPP regulate the phytochrome signals? FyPP is localized in the cytoplasm, indicating that FyPP-mediated dephosphorylation of the phytochromes occurs in the cytoplasm. Phytochrome dephosphorylation by FyPP would mediate the light-induced nuclear localization of the phytochromes, as has been suggested (Ni et al., 1998, 1999). Alternatively, it may regulate the cytoplasmic function of the phytochromes. Our experimental data show that expression of the flowering time genes is affected greatly in FyPP transgenic plants with flowering time alterations (Figure 8B), supporting the idea that FyPP regulates the localization of phytochromes into the nucleus, where they function as the components of transcriptional regulator complexes (Ni et al., 1998). FyPP may either directly trigger the nuclear localization of the dephosphorylated phytochromes or indirectly facilitate the nuclear localization by releasing the phytochromes from certain cytoplasmic anchoring proteins, such as PKS1 (Fankhauser et al., 1999).

The physiologically active Pfr phytochrome is more readily dephosphorylated by FyPP (Figure 5). The Pfr phytochrome with an unphosphorylated Ser-598 residue has a reduced affinity for PKS1 (Fankhauser et al., 1999) but exhibits an increased affinity for PIF3 (Ni et al., 1998). It is more readily translocated into the nucleus, where it binds PIF3, Aux/IAA, or other unidentified transcription factors and regulates gene expression. It is possible that the light-activated phytochrome is desensitized by phosphorylation at Ser-598, the only residue that is phosphorylated specifically in the Pfr form, but sensitized by FyPP-mediated dephosphorylation, as has been suggested (Park et al., 2000a). A similar sensitization/desensitization mechanism has been well documented in the animal photoreceptor rhodopsin (Vishnivetskiy et al., 1999).

FyPP Exerts a Flowering-Specific Role

Two major environmental factors that influence flowering time in Arabidopsis are light and temperature (vernalization). Long days and exposure to low temperature induce flowering (Blázquez et al., 2001; Simpson and Dean, 2002). Molecular mechanisms that underlie the photoperiodic control of flowering time have been studied extensively in recent years, and numerous flowering time genes have been identified (for reviews, see Levy and Dean, 1998; Simpson and Dean, 2002). The phytochromes and cryptochromes are involved in flowering time control but exhibit both synergistic and antagonistic coactions (Mockler et al., 1999; Mazzella et al., 2001), indicating that the light-signaling network involved is complicated.

Analyses of transgenic Arabidopsis plants with the FyPP gene demonstrate that the expression level of the FyPP or AtFyPP gene is in inverse proportion to the timing of flowering. Transgenic plants with reduced FyPP levels showed accelerated flowering, whereas those with increased FyPP levels showed delayed flowering, indicating that FyPP negatively regulates flowering initiation. The altered flowering phenotypes observed in antisense and sense transgenic plants are very similar to those seen in the phyA and phyB mutants, respectively (Figure 6). Although the possibility that either phyA or phyB signal is regulated specifically by FyPP still exists, it is more likely that both signals are regulated by FyPP.

Long days represent a critical and sufficient environmental factor that initiates flowering in Arabidopsis. AtFyPP3 is expressed to a higher level in long days than in short days, as observed with CO (Suárez-López et al., 2001). CO has been suggested to control a signaling pathway that links daylength and the timing of flowering through genetic interactions with FT, TFL, and SOC1 (Onouchi et al., 2000; Suárez-López et al., 2001). FyPP and its orthologs may function in a similar manner. However, they do not seem to regulate all of the signaling pathways downstream of CO. FT gene expression was altered greatly in FyPP transgenic plants as well as in AtFyPP3-deficient mutant plants, but expression of the TFL and LFY genes was not (Figures 8B and 8C). AtFyPP1 is identical to AtFyPP3 except for two residues, and they share the same enzymatic activity and cation requirement. Both genes are expressed predominantly in floral organs. Unexpectedly, AtFyPP1 expression was not influenced by daylength, unlike that of AtFyPP3, suggesting that it functions somewhat differently from AtFyPP3. It may play a constitutive role in phytochrome signaling. Therefore, it is assumed that phytochrome phosphorylation by FyPP or its orthologs is modulated precisely by more than one reversible protein phosphorylation event for elaborate control of flowering time in plants, depending on daylength.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana plants (ecotypes Columbia and Wassilewskija-2) were grown in a controlled culture room at 22°C with a photoperiod of 16 h and RH of 70%. Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation was performed by a modified floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). An Arabidopsis AtFyPP3-deficient mutant was isolated from a pool of T-DNA insertion lines (ecotype Wassilewskija-2; Wisconsin Arabidopsis Knockout Facility, Madison, WI). It had a T-DNA insertion in the third intron of the AtFyPP3 gene, as determined by DNA sequencing.

For light treatments, plants were grown in the dark or under various light wavelengths. Continuous white light was provided by fluorescent FLR40D/A tubes (Osram, Seoul, Korea) at 15 μmol·m−2·s−1. Red and far-red light (10 and 7 μmol·m−2·s−1, respectively) were provided by red and far-red light-emitting diodes equipped in a red/far-red E-30LED1 growth chamber (Percival Scientific, Boone, IA).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using the MATCHMAKER Two-Hybrid System (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The C-terminal half (residues 667 to 1122) of the Arabidopsis phytochrome A was fused in frame to the GAL4 DNA binding domain in the bait plasmid pGBT9. A cDNA library was constructed from 5-day-old dark-grown pea (Pisum sativum) seedlings into the phagemid vector pAD-GAL4-2.1 (Kang et al., 2001). Yeast strain HF7c was transformed with the pGBT9 construct and subsequently with the cDNA library phagemid constructs. Positive transformants (his3+ and lacZ+) were selected in the presence of 20 mM 3-aminotriazole to eliminate false-positive results. Phagemid vectors containing the cDNA clones were recovered by back transformation into Escherichia coli strain XL1-Blue and subjected to DNA sequencing.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis and Comparative Reverse Transcription–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from plant materials using the RNeasy Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Routinely, 20 μg of each RNA sample was denatured in the denaturation buffer [20 mM 3-(N-morpholino)-propanesulfonic acid, 8 mM sodium acetate, and 1 mM EDTA] supplemented with 50% (v/v) formamide and 2.2 M formaldehyde at 65°C for 10 min, resolved on a 1.2% denaturing agarose gel, and transferred onto a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membrane then was hybridized with 32P-labeled gene-specific probe.

Comparative reverse transcription (RT)–PCR was used for some quantitative purposes. Total RNA samples were pretreated extensively with RNase-free DNaseI to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA. Primary cDNA was prepared from 2 μg of total RNA using Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in a 20-μL reaction volume, and 2 μL of the reaction mixture was used for subsequent RT-PCR in a 50-μL reaction volume. The RT-PCR runs were 15 to 28 cycles, depending on the linear range of PCR amplification for each gene, each cycle at 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. One additional cycle at 72°C for 7 min was performed after the last run to allow for trimming of incomplete polymerizations.

Preparation of Phytochrome Photoreceptors

Oat (Avena sativa) phytochrome A was isolated from dark-grown oat seedlings for 5 days as described previously (Lapko and Song, 1995). Protein quality and spectral integrity were examined by SDS-PAGE, zinc blot, and spectral measurements. The protein purity was routinely >92%, and the specific absorbance ratio was 1.0 to 1.1.

The full-size Arabidopsis phytochrome B gene was cloned into the pGEM3Z(+) vector and subsequently subjected to in vitro translation using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System according to the procedure provided by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). One microgram of template DNA and 20 μCi of 35S-Met (catalog No. AG1094; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) were used in a 50-μL reaction volume. ATP was included at a final concentration of 1 μM. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 90 min. In vitro reconstitution with phycocyanobilin (PCB) was performed on ice under green safety light as described (Park et al., 2000b). Two microliters of the PCB solution in DMSO at a concentration of 2 mM was used, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h in the dark.

In Vitro Pulldown Assays

Purified phytochrome A from dark-grown oat seedlings and in vitro translated Arabidopsis phytochrome B were used. The phytochromes were either used directly or autophosphorylated in the presence of 0.5 mM cold ATP for 30 min at room temperature before use. They were then treated with red or far-red light to obtain the Pfr or Pr phytochrome, respectively. The FyPP–glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein was expressed and purified from E. coli cells.

The in vitro pulldown assays were performed essentially as described previously (Kang et al., 2001) with some modifications. Briefly, 2 μg of the recombinant FyPP-GST fusion protein in PBS was first bound to glutathione–Sepharose 4B resin (Amersham Pharmacia) at 4°C for 20 min, and 2 μg of oat phytochrome A was added. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The resin then was washed thoroughly three times with PBS containing 5% Triton X-100, and the bound phytochrome A was eluted by boiling in double-distilled water for 10 min. The eluted samples were run on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a Hybond-P+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia), and analyzed immunologically using a polyclonal anti-phytochrome A antibody.

In vitro pulldown assays with phytochrome B were performed in a manner similar to those with oat phytochrome A but using 5 μL of the in vitro translation mixture, which had been reconstituted in vitro with PCB.

Protein Phosphatase Assays

Recombinant protein phosphatases were expressed as GST fusion proteins via the pGEX-4T-1 E. coli expression vector (Amersham Pharmacia). E. coli strain BL21 was used as the host for protein expression. Cell growth and induction conditions were as described previously (Park et al., 2000b). Protein phosphatase assays were performed essentially as described (Hériché et al., 1997) with a few modifications. Autophosphorylated oat phytochrome A was used as a substrate. One microgram of the substrate was incubated with 0.2 μg of protein phosphatase for up to 30 min at room temperature, analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE, dried on 3MM paper, and subjected to autoradiography. An excess amount of cold ATP was included in the reaction mixtures at a final concentration of 1 mM to keep an equilibrating state of the autophosphorylated phytochrome substrate. Dephosphorylation efficiencies were quantified using ImageMaster VDS (Amersham Pharmacia).

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences described in this article are AF305635 (FyPP) and AF275664 (AtFyPP3). The accession numbers for the other sequences shown in Figure 1 are as follows: Q07098, Q07099, Q07100, P48578, and O04951 (Arabidopsis PP2A-1 to PP2A-5, respectively), S42558 and P48528 (Arabidopsis PPX-1 and PPX-2, respectively), S28173 (human PPX-1), AAA41930 (rat PPX-1), and AAD50050 (AtFyPP1).

Acknowledgments

We thank Il-Ha Lee and Jung-Mook Kim for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Joanne Chory and Kunhua Chen for scientific communications. This work was supported by Kumho Petrochemical Co., Ltd. (Publication 59), and by grants from the Korea Research Foundation (to C.-M.P.) and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Evaluation and Planning and Rural Development Administration (to P.-S.S.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.005306.

References

- Ahmad, M., Jarillo, J.A., Smirnova, O., and Cashmore, A.R. (1998). The CRY1 blue light receptor of Arabidopsis interacts with phytochrome A in vitro. Mol. Cell 1, 939–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnall, D.J., King, R.W., Whitelam, G.C., Boylan, M.T., Wagner, D., and Quail, P.H. (1995). Flowering responses to altered expression of phytochrome in mutants and transgenic lines of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Physiol. 108, 1495–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, M., Koornneef, M., and Putterill, J. (2001). Flowering on time: Genes that regulate the floral transition. Workshop on the molecular basis of flowering time control. EMBO Rep. 2, 1078–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, M.A. (2000). Flower development pathways. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3547–3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, M.A., and Weigel, D. (2000). Integration of floral inductive signals in Arabidopsis. Nature 404, 889–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniotti, M.B., and Griffith, M.E. (2002). “Cross-talk” between cell division and development in plants. Plant Cell 14, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D., Ratcliffe, O., Vincent, C., Carpenter, R., and Coen, E. (1997). Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275, 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandok, M.R., and Sopory, S.K. (1996). Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation steps are key events in the phytochrome-mediated enhancement of nitrate reductase mRNA levels and enzyme activity in maize. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251, 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, G., Yi, H., Lee, J., Kwon, Y.-K., Soh, M.-S., Shin, B., Luka, Z., Hahn, T.-R., and Song, P.-S. (1999). Phytochrome signaling is mediated through nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2. Nature 401, 610–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Carmona, A., Chen, D.L., Yeh, K.C., and Abel, S. (2000). Aux/IAA proteins are phosphorylated by phytochrome in vitro. Plant Physiol. 124, 1728–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C. (2000). Phytochromes as light-modulated protein kinases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (1997). Light control of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (1999). Light receptor kinases in plants. Curr. Biol. 9, R123–R126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., Yeh, K.-C., Lagarias, J.C., Zhang, H., Elich, T.D., and Chory, J. (1999). PKS1, a substrate phosphorylated by phytochrome that modulates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 1539–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H., Mockler, T., Duong, H., and Lin, C. (2001). SUB1, an Arabidopsis Ca2+-binding protein involved in cryptochrome and phytochrome coaction. Science 291, 487–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter, K., Frohnmeyer, H., Kircher, S., Kunkel, T., Muhlbauer, S., and Schäfer, E. (1994). Light induces rapid changes of the phosphorylation pattern in cytosol of evacuolated parsley protoplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 5038–5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hériché, J.-K., Lebrin, F., Rabilloud, T., Leroy, D., Chambaz, E.M., and Goldberg, Y. (1997). Regulation of protein phosphatase 2A by direct interaction with casein kinase 2α. Science 276, 952–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.-G., Ju, Y., Kim, D.-H., Chung, K.-S., Fujioka, S., Kim, J.-I., Dae, H.-W., Yoshida, S., Takatsuto, S., Song, P.-S., and Park, C.-M. (2001). Light and brassinosteroid signals are integrated via a dark-induced small G-protein in etiolated seedling growth. Cell 105, 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyse, S.M. (2000). Protein phosphatases and the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, S., Kozma-Bognar, L., Kim, L., Adam, E., Harter, K., Schäfer, E., and Nagy, F. (1999). Light quality–dependent nuclear import of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A and B. Plant Cell 11, 1445–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Y., Kaya, H., Goto, K., Iwabuchi, M., and Araki, T. (1999). A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 286, 1960–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef, M., Alonso-Blanco, C., Peeters, A.J.M., and Soppe, W. (1998). Genetic control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 345–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapko, V.N., Jiang, X.Y., Smith, D.L., and Song, P.-S. (1999). Mass spectrometric characterization of oat phytochrome A: Isoforms and posttransformational modifications. Protein Sci. 8, 1032–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapko, V.N., and Song, P.-S. (1995). A simple and improved method of isolation and purification for native oat phytochrome. Photochem. Photobiol. 62, 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., Suh, S.-S., Park, E., Cho, E., Ahn, J.H., Kim, S.-G., Lee, J.S., Kwon, Y.M., and Lee, I. (2000). The AGAMOUS-LIKE 20 MADS domain protein integrates floral inductive pathways in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 14, 2366–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Y.Y., and Dean, C. (1998). The transition to flowering. Plant Cell 10, 1973–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Li, J., Qu, L., Hager, J., Chen, Z., Zhao, H., and Deng, X.W. (2001). Light control of Arabidopsis development entails coordinated regulation of genome expression and cellular pathways. Plant Cell 13, 2589–2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez, A., Lopez-Ochoa, L., Arguello-Astorge, G., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2002). Functional properties and regulatory complexity of a minimal RBCS light-responsive unit activated by phytochrome, cryptochrome, and plastid signals. Plant Physiol. 128, 1223–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Más, P., Devlin, P.F., Panda, S., and Kay, S.A. (2000). Functional interaction of phytochrome B and cryptochrome 2. Nature 408, 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzella, M.A., Cerdán, P.D., Staneloni, R.J., and Casal, J.J. (2001). Hierarchical coupling of phytochromes and cryptochromes reconciles stability and light modulation of Arabidopsis development. Development 128, 2291–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszaros, T., Miskolczi, P., Ayaydin, F., Pettko-Szandtner, A., Peres, A., Magyar, Z., Horvath, G.V., Bako, L., Feher, A., and Dudits, D. (2000). Multiple cyclin-dependent kinase complexes and phosphatases control G2/M progression in alfalfa cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockler, T.C., Guo, H., Yang, H., Duong, H., and Lin, C. (1999). Antagonistic actions of Arabidopsis cryptochromes and phytochrome B in the regulation of floral induction. Development 126, 2073–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, F., Kircher, S., and Schäfer, E. (2000). Nucleo-cytoplasmic partitioning of the plant photoreceptors phytochromes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, M.M., and Chory, J. (1998). Genetic interactions between phytochrome A, phytochrome B, and cryptochrome 1 during Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 118, 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, M.M., Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (2000). Light: An indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 14, 257–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus, G., Bowler, C., Kern, R., and Chua, N.H. (1993). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent and -independent phytochrome signal transduction pathways. Cell 73, 937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M., Tepperman, J.M., and Quail, P.H. (1998). PIF3, a phytochrome-interacting factor necessary for normal photoinduced signal transduction, is a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein. Cell 95, 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M., Tepperman, J.M., and Quail, P.H. (1999). Binding of phytochrome B to its nuclear signaling partner PIF3 is reversibly induced by light. Nature 400, 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, H., Matsui, M., and Deng, X.W. (2001). Overexpression of the heterotrimeric G-protein α-subunit enhances phytochrome-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1639–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onouchi, H., Igeño, M.I., Périlleux, C., Graves, K., and Coupland, G. (2000). Mutagenesis of plants overexpressing CONSTANS demonstrates novel interactions among Arabidopsis flowering-time genes. Plant Cell 12, 885–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.-M., Bhoo, S.-H., and Song, P.-S. (2000. a). Inter-domain crosstalk in the phytochrome molecules. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.-M., Shim, J.-Y., Yang, S.-S., Kang, J.-G., Kim, J.-I., Luka, Z., and Song, P.-S. (2000. b). Chromophore-apoprotein interactions in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 phytochrome Cph1. Biochemistry 39, 6349–6356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro, M., and Coupland, G. (1998). The control of flowering time and floral identity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 117, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, P.H., and Coupland, G. (2001). Analysis of flowering time control in Arabidopsis by comparison of double and triple mutants. Plant Physiol. 126, 1085–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux, S.J. (1994). Signal transduction in phytochrome responses. In Photomorphogenesis in Plants, 2nd ed, R.E. Kendrick and G.H.M. Kronenberg, eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff), pp. 187–209.

- Samach, A., Onouchi, H., Gold, S.E., Ditta, G.S., Schwarz-Sommer, Z., Yanofsky, M.F., and Coupland, G. (2000). Distinct roles of CONSTANS target genes in reproductive development of Arabidopsis. Science 288, 1613–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, J. (1993). Protein phosphatase activity is required for light-inducible gene expression in maize. EMBO J. 12, 3497–3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, G.G., and Dean, C. (2002). Arabidopsis, the Rosetta stone of flowering time? Science 296, 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, J.M., Collinge, M.A., Smith, R.D., Horn, M.A., and Walker, J.C. (1994). Interaction of a protein phosphatase with an Arabidopsis serine-threonine receptor kinase. Science 266, 793–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-López, P., Wheatley, K., Robson, F., Onouchi, H., Valverde, F., and Coupland, G. (2001). CONSTANS mediates between the circadian clock and the control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature 410, 1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Higgins, D.G., and Gibson, T.J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virshup, D.M. (2000). Protein phosphatase 2A: A panoply of enzymes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnivetskiy, S.A., Paz, C.L., Schubert, C., Hirsch, J.A., Sigler, P.B., and Gurevich, V.V. (1999). How does arrestin respond to the phosphorylated state of rhodopsin? J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11451–11454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Ma, L.-G., Li, J.-M., Zhao, H.-Y., and Deng, X.W. (2001). Direct interaction of Arabidopsis cryptochromes with COP1 in light control development. Science 294, 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, D., Alvarez, J., Smyth, D.R., Yanofsky, M.F., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1992). LEAFY controls floral meristem identity in Arabidopsis. Cell 69, 843–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, R.S., Anderson, K.A., Means, A.R., and Wadzinski, B.E. (1998). A signaling complex of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV and protein phosphatase 2A. Science 280, 1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.-Q., Tang, R.-H., and Cashmore, A.R. (2001). The signaling mechanism of Arabidopsis CRY1 involves direct interaction with COP1. Plant Cell 13, 2573–2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, K.C., and Lagarias, J.C. (1998). Eukaryotic phytochromes: Light-regulated serine/threonine protein kinases with histidine kinase ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13976–13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]