Abstract

We report that disruption of the mouse TOP3β gene encoding DNA topoisomerase IIIβ, one of the two mammalian type IA DNA topoisomerases, leads to a progressive reduction in fecundity. The litter size in crosses of top3β−/− mice decreases over time and through successive generations, and this decrease seems to reflect embryonic death rather than impaired fertilization. These observations are suggestive of a gradual accumulation of chromosomal defects in germ cells lacking DNA topoisomerase IIIβ, and this interpretation is supported by the observation of a high incidence of aneuploidy in the spermatocytes of infertile top3β−/− males. Cytogenetic examination of spermatocytes of wild-type mice also indicates that DNA topoisomerase IIIβ becomes prominently associated with the asynaptic regions of the XY bivalents during pachytene, and that there is a time lag between the appearance of chromosome-bound DNA topoisomerase IIIβ and Rad51, a protein known to be involved in an early step of homologous recombination. We interpret these findings, together with the known mechanistic characteristics of different subfamilies of DNA topoisomerases, in terms of a specific role of a type IA DNA topoisomerase in the resolution of meiotic double-Holliday junctions without crossing over. This interpretation is most likely applicable to mitotic cells as well and can explain the universal presence of at least one type IA DNA topoisomerase in all organisms.

The DNA topoisomerases are enzymes that catalyze the passage of one DNA strand or double helix through another. These enzymes participate in nearly all transactions of intracellular DNA, and four distinct subfamilies of the enzymes, denoted type IA, IB, IIA, and IIB, are known (1–3). Among the four subfamilies, only the type IA enzymes are present in all organisms. Examples are bacterial DNA topoisomerase I and III, yeast DNA topoisomerase III, human DNA topoisomerase IIIα and IIIβ, and the “reverse gyrases” found in archaea (1–3). This omnipresence of the type IA enzymes suggests that they play an essential role in processing intracellular DNA, and genetic studies of microorganisms have provided strong support of this idea. Escherichia coli lacking both of the type IA DNA topoisomerases, for example, is not viable (4). Similarly, yeast top3 mutants lacking DNA topoisomerase III (Top3), the only type IA enzyme in yeasts, exhibit a complex phenotype including slow growth, hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, genome instability, and low viability (5–7).

There is substantial evidence that the requirement of the type IA DNA topoisomerases is related to their role in homologous recombination and recombination-mediated repair. Whereas sporulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae top3 diploids yields no viable spores, this lethality can be prevented by blocking meiotic recombination (7). Concordantly, inactivation of the E. coli recA gene, which is essential for homologous recombination, restores viability of a topA topB double mutant lacking both DNA topoisomerases I and III (4). Earlier studies also showed that the defects of mitotic yeast top3 cells could largely be suppressed by mutations in a helicase of the RecQ family, the Sgs1 protein in S. cerevisiae and the Rqh1 protein in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (6, 8, 9). Extensive studies of physical and functional interactions between the type IA DNA topoisomerases and RecQ helicases have been carried out (6, 9–15), prompted by the identification of the human Bloom and Werner syndrome proteins as RecQ helicases (16, 17). The results of these studies are consistent with a mechanism suggested earlier: a RecQ helicase is involved in the formation of a certain DNA structure, and a type I DNA topoisomerase is required in the subsequent processing of this structure (6). Recent data suggest that this putative DNA structure is an intermediate of homologous recombination, the strongest evidence being the suppression of yeast top3 defects by mutations in a number of known homologous recombination genes (refs. 18 and 19; see ref. 18 for citation of additional references).

The functional importance of the type IA DNA topoisomerases in multicellular organisms is demonstrated by studies in the mouse model. Mouse top3α−/− embryos lacking DNA topoisomerase IIIα (Top3α) were found to die shortly after implantation (20). Whereas top3β−/− animals lacking DNA topoisomerase IIIβ (Top3β) seem to develop to maturity with no apparent defects, the average lifespan of the mutant mice is only half as long as their TOP3β+/+ littermates (21). We report here that disruption of the mouse TOP3β gene also leads to a progressive decrease in litter size, over time and through successive generations. This progressive decrease suggested an accumulation of chromosomal defects in the mutant animals. Indeed, a high incidence of aneuploidy in the germ cells of infertile top3β−/− males was observed. These and other results, together with the known mechanistic characteristics of the various subfamilies of DNA topoisomerases (1–3), led us to propose a molecular model in which a type IA DNA topoisomerase is involved in the resolution of the majority of double-Holliday junctions (DHJ) that are formed in meiotic recombination (22). We believe that this interpretation can be extended to mitotic cells as well and can explain the universal presence of the type IA enzymes in all organisms.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Maintenance and Breeding.

Targeted disruption in the mouse TOP3β gene was reported (21). Mice were housed in microisolation cages and fed ad libitum. Mating of individual pairs was initiated when the animals reached 8 weeks of age, and the litter size from each individual pair was monitored over a period of 6–8 months.

Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization of Meiotic Metaphases.

Chromosome-specific probes were purchased from Cambio (Cambridge, U.K.), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was carried out following the procedure suggested by the supplier of the probes. Fluorescent images were captured at ×1,000 magnification by using an Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Individual images recorded through different filters were false-colored by the use of PHOTOSHOP software (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Antibodies.

Mouse Cor1 antibodies and the centromere-specific human CREST serum were obtained from sources noted (23), and rabbit antibodies against Rad51 were purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). To obtain polyclonal antibodies against mouse Top3β, a DNA fragment corresponding to base pairs 1858–2592 of the mouse TOP3β coding sequence was amplified by the use of a pair of primers 5′-GGGAATTCCATATGCCCCTCTCGCGCTGTGGGAAGT-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCTCATCATACAAAGTAAGCAGCCAGAGCGTAC-3′ in a PCR. The underlined nucleotides introduce a NdeI and a BamHI restriction site into the reaction product. Nucleotide sequencing of the cloned Top3β fragment showed a difference of three base pairs (shown in bold fonts in the primer sequences) from the TOP3β coding sequence reported in GenBank (accession no. NM_011624), which would in turn express a protein with a tyrosyl residue replacing Ser-855 of the reported Top3β protein sequence. This alteration was probably introduced during the PCR. For the purpose of eliciting Top3β-specific polyclonal antibodies, such a change was expected to pose minimal effect and was ignored. The amplified DNA was trimmed at its ends with NdeI and BamHI restriction endonucleases, and cloned into the corresponding sites in pET15b (Invitrogen) to give a plasmid overexpressing a 27-kDa fragment of Top3β that contained residues 620–863 of the intact enzyme plus a hexahistidine tag at the N terminus. The protein was overexpressed in E. coli BL21 cells, purified from cell lysates by chromatography over an Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and used in eliciting rabbit antibodies. The same protein was also immobilized on a Sepharose column for affinity purification of antibodies specific to it. Affinity-purified Top3β antibodies were further concentrated by chromatography over protein A-Sepharose (Invitrogen), dialyzed against standard PBS plus 0.01% sodium azide, and stored at −80°C. The purified antibodies were found to be highly specific to Top3β and showed no crossreactivity to Top3α in mouse cell extracts.

Meiotic Spreads.

Testes cells resuspended in MEM were spread on the surface of 100 mM NaCl and picked up with glass slides. Fixation of cells adhered to the slides was done by immediately dipping the slides in 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde plus 0.03% SDS for 3 min, and then in 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for another 3 min. The slides were rinsed in H2O containing 0.4% Photoflo 200 (Eastman Kodak), briefly air-dried, and then successively washed in PBS plus 0.4% Photoflo 200, PBS plus 0.05% Triton X-100, and PBS plus 10% (vol/vol) antibody dilution buffer [ADB, which is PBS containing 10% (vol/vol) goat serum, 3% (vol/vol) BSA, and 0.05% Triton X-100]. Stocks of antibodies against Top3β and Rad51 were diluted 1:100 with ADB. Mouse antibodies against Cor1 (Scp3) and human CREST sera were diluted 1:500 in ADB. Diluted primary antibodies were incubated with the treated cells on slides overnight at room temperature, and the slides were then washed in the series of PBS solutions described above. Appropriate fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies were diluted 1:500 in ADB and incubated with cells adhered to the slides for 1 h at 37°C. After washing successively in PBS containing 0.4% Photoflo 200, PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, and again in PBS containing 0.4% Photoflo 200, the slides were rinsed three times with 0.4% Photoflo 200 in H2O and mounted in ProLong (Molecular Probes) plus 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma).

Results

Reduction of top3β−/− Litter Size Over Time and Through Generations.

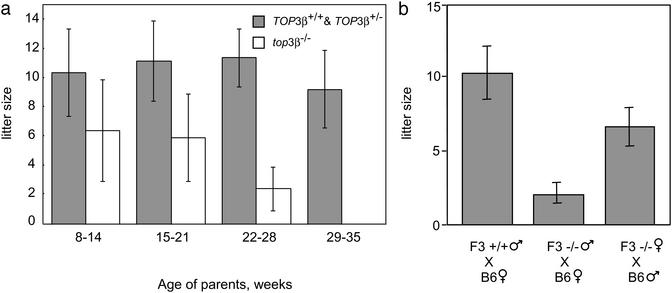

Fig. 1a depicts the average litter size in the mating of F2 top3β−/− siblings over a period of ≈6 months (F2 refers to the second generation offspring of the founding chimeras). Whereas in intercrosses of TOP3β+/+ or top3β+/− animals between 8 and 36 weeks of age the average litter size stayed around 10, in crosses of top3β−/− siblings it dropped from around 6 for mature F2 animals younger than 18 weeks of age to close to 0 for 29- to 35-week-old animals that showed no sign of compromised health or agility. When the F3s derived from breeding of F2 top3β−/− mice were again intercrossed, the average litter size was even lower. For six mating pairs starting from an age of ≈8 weeks, over an 8-month period four produced no offspring, and the other two produced two litters each with an average litter size of 2.5. The reduction in fertility of top3β−/− mice seemed to reflect embryonic death rather than impaired fertilization. Dissection of the females of the F3 breeding pairs that produced no offspring showed that one had five decidual swellings at 10.5 days postcoitus (dpc), and another had two at 13.5 dpc in its uterine horns. No intact embryos were observed in these decidual swellings, most of which were undergoing resorption. By crossing top3β−/− mice with wild-type C57BL/6T animals, it was further observed that fertility was more severely compromised in the mutant males than in the mutant females (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Average litter size as a function of the age of the parents. (a) Each of the mating pairs was kept in a separate cage, and births over a 6-month period were monitored. Data for births during successive 6-week periods (one to two litters) were grouped together, and the average litter size of top3β−/− mice was calculated from data recorded for three mating pairs 8 weeks of age at the start of the experiment. The control group included two TOP3β+/+ and one top3β+/− mating pairs that were littermates of the top3β−/− mice. No significant difference in litter size was observed among the TOP3β+/+ and top3β+/− pairs, and thus data for the control group were combined. Error bars represent SDs. (b) Average litter sizes of crosses between male F3 TOP3β+/+ mice and female C57BL/6T mice (left bar), male F3 top3β−/− and female C57BL/6T mice (middle bar), and female F3 top3β−/− and male C57BL/6T mice (right bar). F3 refers to third generation offspring from the founding chimeras. A minimum of three mating pairs were used in each combination, and mating was started and ended at 8 and 36 weeks of age, respectively. Error bars represent SDs.

Chromosomal Anomalies in top3β−/− Spermatocytes.

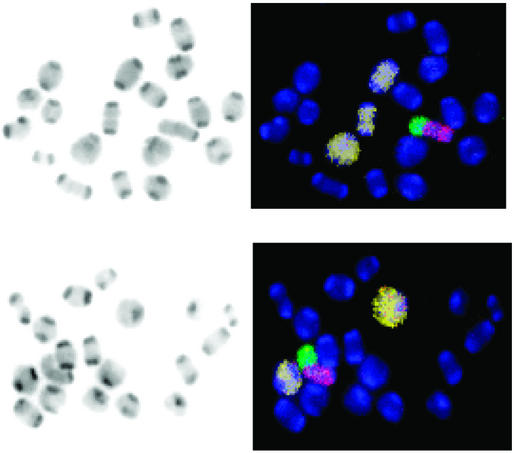

The above results on the progressive reduction in the fertility of top3β−/− mice are suggestive of an accumulation of genetic defects in these animals, over time and through successive generations, particularly in the male germ cells. Therefore, we examined the meiotic metaphases in infertile top3β−/− males and in TOP3β+/+ control animals by fluorescence in situ hybridization. A mixture of differently tagged probes that specifically hybridize to chromosomes 1, 3, and 16 were biotin-tagged for subsequent binding of Cy5-conjugated avidin, and probes specific to the X and Y chromosome were tagged with the fluorescent dye Cy3 and FITC, respectively. Two examples of meiotic metaphase I (M I) chromosome pairs are depicted in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 Left shows the fluorescence image (in black and white) of the DAPI-stained chromosomes of a spermatocyte, and Fig. 2 Right shows the merged fluorescence images of the same set of chromosomes, with the three Cy5-marked autosomes in pale yellow, the Cy3-marked X chromosome in red, and the FITC-marked Y chromosome in green. It can be readily seen that the full complement of 20 chromosome pairs are present in Fig. 2 Upper, but one of the three yellow-painted autosome pairs is absent in Fig. 2 Lower. Examination of the fluorescence-painted chromosomes in a total of 188 sets of TOP3β+/+ M I chromosomes revealed that the vast majority of these (186) showed no anomalies; only one set lacked one of the three painted autosomes, and another set lacked the XY pair. Thus, these TOP3β+/+ metaphases showed a low incidence of aneuploidy among the painted chromosomes (2/188), and no other types of chromosomal anomalies were identifiable. In contrast, for the top3β−/− M I chromosomes, there was a much higher frequency of aneuploidy. For a total of 225 sets counted, 19 showed the loss of one of the painted autosome or sex chromosome pairs, 10 showed a loss of either an X or Y chromosome, and 2 showed the loss of more than one painted chromosome pair. Hyperploidy was also observed in two sets of the chromosomes: one with an extra painted autosome pair, and the other with an extra Y chromosome. Thus, a total of about 15% of the top3β−/− M I sets examined showed aberrations in the painted chromosomes, mostly aneuploidies. Numeric anomalies were again seen in meiotic metaphase II (M II) chromosomes in top3β−/− but not in TOP3β+/+ testicular cells. For 99 sets of TOP3β+/+ M II chromosomes, no anomaly in the painted chromosomes was observed; for a total of 129 sets of top3β−/− M II chromosomes, hypoploidy in the painted chromosomes was found in 10 cells and hyperploidy in 8. Defects other than anomalies in chromosomal numbers, such as chromosomal translocations or fragmentation, were not seen among a total of several hundred sets of the M I and M II chromosomes examined. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Two examples of M I chromosomes of TOP3β+/+ and top3β−/− mouse testicular cells. Two 6-month-old TOP3β+/+ and five 3- to 6-month-old top3β−/− mice were used to generate metaphase chromosomes. Hypotonically treated cells were fixed in methanol:acetic acid (3:1 vol:vol), and chromosome spreads on glass slides were prepared. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with a mixture of differently tagged probes was then carried out, and the chromosomes were also stained with DAPI before viewing in a fluorescence microscope. (Left) The DAPI stain in black and white. (Right) The merged fluorescence images, with the Cy5-painted chromosomes 1, 3, and 16 in pale yellow, the Cy3-painted X chromosome in red, the FITC-painted Y chromosome in green, and the other chromosomes in blue. (Upper) The full complement of 20 chromosome pairs. In the pair of images of chromosomes from a top3β−/− cell (Lower), one of the Cy5-painted autosome pairs is missing.

Table 1.

Anomalies in painted meiotic metaphases from top3β−/− spermatocytes

| Genotype | Meiotic cells | Total no. counted | Observations of the painted chromosomes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal, % | Hypoploidy, % | Hyperploidy, % | |||

| TOP3β+/+ | M I | 188 | 186 (98.9) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| M II | 99 | 99 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| top3β−/− | M I | 225 | 192 (85.3) | 31 (13.8) | 2 (0.9) |

| M II | 129 | 111 (86.0) | 10 (7.8) | 8 (6.2) | |

The cytogenetic results presented above support the notion that infertility of the top3β−/− mice is caused by an accumulation of chromosomal defects, particularly aneuploidies, in germ cells. For animals of the same age, the male germ cells have undergone more cell divisions than female ones, and this difference may account for the more severe infertility in the top3β−/− males than the top3β−/− females of the same age and generation. These results also imply a well-conserved role of the type IA DNA topoisomerases in the proper segregation of chromosomes, in organisms ranging from E. coli (4) and yeast (6–9) to mouse. In humans, aneuploidy is a particularly prevalent cause of infertility and miscarriages (24, 25), although any plausible link to the type IA DNA topoisomerases is yet to be explored.

Localization of DNA Topoisomerase IIIβ on Meiotic Chromosomes.

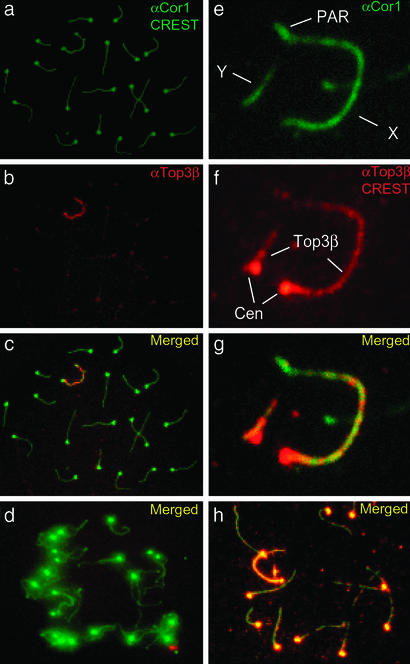

To gain further insight on the cellular roles of Top3β, meiotic chromosome spreads were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy by using antibodies specific to Top3β. In TOP3β+/+ testicular cells, Top3β was prominently localized along the axes of the asynapsed portion of the XY bivalents during pachytene (Fig. 3 a–c); on the autosomes, during pachytene, punctated foci of the protein were visible in fluorescence micrographs after longer exposure (Fig. 3h). During stages other than pachytene, Top3β was largely invisible (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Localization of DNA topoisomerase IIIβ (Top3β) to meiotic chromosomes at pachytene. (a–d) DAPI-stained chromosomes were painted with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies against antibodies that are specific to Cor1, Top3β, or a centromere-associated protein. (a) The axial elements and centromeres are highlighted in green. (b) Top3β is highlighted in red. (c) The images a and b were merged. (d) The merged images of a diplotene cell; little chromosome-associated Top3β signal was discernible in this and other diplotene cells. (e–g) Magnified images of an XY pair. (e) The chromosome axes were marked by antibodies against Cor1, and the asynapsed and the synapsed pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of the XY pair are readily visible. In f and g, the latter being the merged images of e and f, antibodies specific to Top3β were seen to be prominently associated with the asynapsed portion of the XY pair. Cen, centromere. (h) When a longer exposure time was used in imaging, the merged images of the green anti-Cor1 stain and the red anti-Top3β stain revealed punctated red fluorescence foci along the axes of the autosomes. The bright red arc (in the 10 o'clock direction from the center of the micrograph) is the XY pair. In these experiments, mouse antibodies against Cor1, rabbit antibodies against Top3β, and human CREST sera that specifically stain the centromeres were used, and various fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were used to highlight the particular primary antibodies.

As expected, in top3β−/− testicular cells, no Top3β signal was detectable at any stage (data not shown). We have also examined meiotic cells derived from ovaries of TOP3β+/+ E17.5 embryos, and no prominent association of Top3β with the X chromosome was seen during all stages of meiosis (data not shown). Thus, the prominent presence of Top3β on the asynapsed portions of the XY bivalents during pachytene is most likely related to the asynaptic structure of the bivalents rather than other particular properties of the sex chromosomes. This pattern of chromosomal localization is reminiscent of those observed in studies of a number of proteins, including XY40 (26), ATR (27), asynaptin (28), Rad50 and Mre11 (29), Xmr (30), Rad51 (31), and histone H2AX (32). Several of these proteins are well known for their involvement in recombination-repair (33–35).

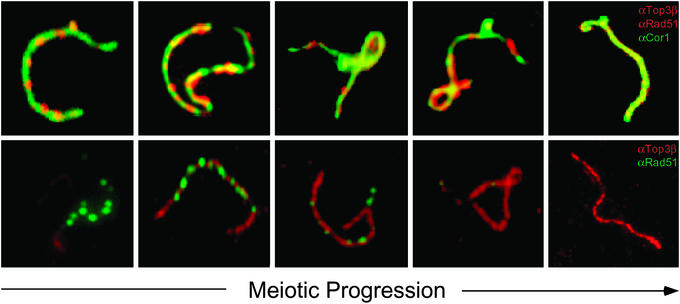

Relative Time of Appearance of DNA Topoisomerase IIIβ and Rad51 During Meiotic Progression.

Because the type IA DNA topoisomerases seem to play a role in homologous recombination (4, 7, 18, 19), we immunostained both Top3β and Rad51, a protein known to be involved in this process (33–35), to determine the relative time of appearance of these two proteins on the XY bivalents. As reported (31), punctate Rad51 foci appeared on the developing chromosome axes at leptotene, persisted on the asynapsed portion of the X chromosome axis after the disappearance of most autosomal Rad51 foci around mid-pachytene, and finally disappeared from the X chromosome at later stages of pachytene. Interestingly, coincident with the disappearance of the Rad51 foci on the X chromosome, Top3β signal progressively spread over the entire asynapsed regions of the XY chromosome axes (Fig. 4). These observations indicate that Top3β is likely to act after Rad51 during meiotic progression, which is consistent with a role of the type IA enzyme in the processing of an intermediate of Rad51-mediated homologous recombination (36). Our observations in mouse meiotic cells are also reminiscent of the finding in mitotic S. pombe cells after inducing double-strand breaks by ionizing radiation (37). In the latter case, Top3 foci appeared significantly later than foci containing Rhp51, the S. pombe homologue of Rad51 (37). Together, these results are suggestive of a well conserved role of the type IA DNA topoisomerases in recombination-repair.

Figure 4.

Relative time of appearance of Top3β and Rad51 on the XY pair during pachytene. (Upper) The chromosome axes were stained green, and both Top3β and Rad51 were stained red. (Lower) The chromosome axes were not stained, Top3β was stained red, and Rad51 was stained green. Staging of meiotic progression was based on the morphology of the Cor1-marked chromosome axes and the known time course of Rad51 appearance (23, 36). (Lower) Clear illustrations of the delayed appearance of the Top3β red fluorescence relative to that of the green Rad51 foci. The same conclusion can be drawn from Upper: whereas Top3β and Rad51 were both painted red, the former showed as patches along the chromosome axes and the latter showed as punctated foci.

Discussion

The high incidence of aneuploidies in top3β−/− spermatocytes, similar to the segregation defect observed in yeast top3 mutants, is likely to reflect a direct role of the type IA DNA topoisomerase in chromosome segregation. What might be the molecular basis of such a role?

Mechanistically, a type IA DNA topoisomerase might participate in the resolution of two types of chromosome junctions: chromosome pairs that are topologically linked by intertwined DNA strands in DNA segments that has yet to replicate (1, 3, 38), and chromosome pairs joined by structures resulting from recombination, such as the Holliday junctions (3, 22, 39, 40). It seems likely, however, that intertwines between unreplicated DNA strands can also be resolved by a pathway that does not require a type IA DNA topoisomerase: the intertwines between complementary DNA strands in an unreplicated DNA segment can be transposed, with the aid of a DNA helicase, into double-stranded intertwines in an adjacent region of newly duplicated DNA, which can then be removed by a type II DNA topoisomerase (41). Thus, the untwining of unreplicated parental DNA strands is unlikely to be the major cellular role of the type IA DNA topoisomerases. Furthermore, any postulate invoking a critical role of a type IA DNA topoisomerase in the resolution of newly replicated chromosome pairs cannot explain the observation that the defects owing to inactivation of these enzymes can be suppressed by mutations in homologous recombination genes (4, 7–9).

The plausible involvement of the DNA topoisomerases in the resolution of chromosomal pairs joined by Holliday junctions has been raised previously, based on genetic data showing that the majority of recombination events do not lead to products with crossovers (40). In mouse meiotic cells, the number of chromosome-associated Rad51 foci was also found to be much higher than the events of reciprocal recombination (36). The DNA topoisomerases are ideal in the resolution of DNA intertwines without crossing over; in a DNA topoisomerase-mediated reaction, no DNA strand exchange occurs, and thus no products with crossovers are formed. Mechanistically, the resolution of a single Holliday junction by branch migration to an existing nick or DNA end might involve a DNA topoisomerase, owing to the supercoiling of DNA during branch migration (40). However, a specific requirement of a type IA enzyme, which is incapable of removing positive supercoils and is marginally effective in removing negative supercoils, would seem rather unlikely in the presence of type IB and IIA DNA topoisomerases that are very efficient in the removal of both positive and negative supercoils (1–3).

The resolution of a DHJ, on the other hand, may specifically involve a type IA enzyme (3). The heteroduplex intertwines in a DHJ cannot be transposed into double-stranded intertwines for resolution by a type II DNA topoisomerase (3). Although a type IB DNA topoisomerase can also catalyze the passage of one DNA single strand through another, its action is believed to require the binding of the enzyme to a short double-stranded DNA segment (2). Therefore, it is likely that a type IB DNA topoisomerase is incapable of removing the last couple of single-stranded intertwines. Thus, among the various DNA topoisomerases, the type IA enzymes seem to be uniquely suited in the complete removal of the heteroduplex intertwines in a DHJ, with the help of one or more DNA helicases (3). In S. cerevisiae, there is strong evidence that meiotic recombination goes through the formation of a double Holliday structure (22). Thus, the specific involvement of a type IA DNA topoisomerase in the resolution of DHJ in meiotic cells is particularly attractive. Our finding that the Top3β protein appears after Rad51 on asynapsed XY chromosomes is entirely consistent with a role of Top3β in resolving the majority of the double-Holliday intermediates that are formed in the Spo11-Rad51 pathway.

We believe that the specific involvement of a type IA DNA topoisomerase in the resolution of DHJ is not limited to meiosis. In mitotic cells, several homologous recombination pathways may be used for the repair of DNA damage, including damaged replication forks (33–35). Some of these, such as the single-stranded annealing and the one-sided strand invasion pathway, do not involve DHJ formation, but others may (34, 35). Whenever there is a significant recombination-repair pathway that goes through a DHJ, a type IA DNA topoisomerase, in conjunction with a DNA helicase, would be important in its resolution without effecting crossing over. In the absence of Top3, any unresolved interchromosomal DHJ during chromosome segregation is likely to result in numeric chromosome abnormality. Resolution of DHJ by Top3-independent mechanisms, through breakage of DNA strands or a resolvase-type reaction, can lead to a high probability of crossing over and thus an increase in genome instability. The postulated role of the type IA DNA topoisomerases in DHJ resolution also suggests that one important mechanism of suppressing the mitotic phenotype of yeast top3 nulls would be the inactivation of proteins that are required in a recombination-repair pathway, presumably a major pathway that goes through a DHJ intermediate. It should be of interest to test whether many of the suppressor mutations, including S. cerevisiae sgs1 and S. pombe rqh1, fall in this class.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nadine Kolas for the preparation of female meiotic spreads and for technical advice, Nancy Kleckner and Beth Weiner for the use of a fluorescence microscope and advice, Neil Hunter and Rita Cha for comments and discussion, and Barbara Spyropoulos and Renate Helmiss for help with the graphics. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM24544 and CA47958.

Abbreviations

- Top3

DNA topoisomerase III

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- M I

meiotic metaphase I

- M II

meiotic metaphase II

- DHJ

double-Holliday junction

References

- 1.Wang J C. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champoux J J. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J C. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Q, Pongpech P, DiGate R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9766–9771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171579898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallis J W, Chrebet G, Brodsky G, Rolfe M, Rothstein R. Cell. 1989;58:409–419. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90855-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gangloff S, McDonald J P, Bendixen C, Arthur L, Rothstein R. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8391–8398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gangloff S, de Massy B, Arthur L, Rothstein R, Fabre F. EMBO J. 1999;18:1701–1711. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maftahi M, Han C S, Langston L D, Hope J C, Zigouras N, Freyer G A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4715–4724. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin A, Wang S W, Toda T, Norbury C, Hickson I D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4050–4058. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.20.4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett R J, Noirot-Gros M F, Wang J C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26898–26905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fricke W M, Kaliraman V, Brill S J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8848–8855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009719200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullen J R, Kaliraman V, Brill S J. Genetics. 2000;154:1101–1114. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duno M, Thomsen B, Westergaard O, Krejci L, Bendixen C. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;264:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s004380000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Davies S L, North P S, Goulaouic H, Riou J F, Turley H, Gatter K C, Hickson I D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9636–9644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onodera R, Seki M, Ui A, Satoh Y, Miyajima A, Onoda F, Enomoto T. Genes Genet Syst. 2002;77:11–21. doi: 10.1266/ggs.77.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis N A, Groden J, Ye T Z, Straughen J, Lennon D J, Ciocci S, Proytcheva M, German J. Cell. 1995;83:655–666. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu C E, Oshima J, Fu Y H, Wijsman E M, Hisama F, Alisch R, Matthews S, Nakura J, Miki T, Ouais S, et al. Science. 1996;272:258–262. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shor E, Gangloff S, Wagner M, Weinstein J, Price G, Rothstein R. Genetics. 2002;162:647–662. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oakley T J, Goodwin A, Chakraverty R K, Hickson I D. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2002;1:463–482. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, Wang J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1010–1013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwan K Y, Wang J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5717–5721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101132498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Cell. 1995;83:783–791. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moens P B, Pearlman R E, Heng H H, Traut W. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1998;37:241–262. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McFadden D E, Friedman J M. Mutat Res. 1997;396:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassold T, Hunt P. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:280–291. doi: 10.1038/35066065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsheimer M, Imamichi Y, Heid H, Benavente R. Chromosoma. 1997;106:308–314. doi: 10.1007/s004120050252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keegan K S, Holtzman D A, Plug A W, Christenson E R, Brainerd E E, Flaggs G, Bentley N J, Taylor E M, Meyn M S, Moss S B, et al. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2423–2437. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner J M, Mahadevaiah S K, Benavente R, Offenberg H H, Heyting C, Burgoyne P S. Chromosoma. 2000;109:426–432. doi: 10.1007/s004120000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eijpe M, Offenberg H, Goedecke W, Heyting C. Chromosoma. 2000;109:123–132. doi: 10.1007/s004120050420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Escalier D, Garchon H J. Chromosoma. 2000;109:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s004120000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moens P B, Chen D J, Shen Z, Kolas N, Tarsounas M, Heng H H, Spyropoulos B. Chromosoma. 1997;106:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s004120050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Celeste A, Petersen S, Romanienko P J, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen H T, Sedelnikova O A, Reina-San-Martin B, Coppola V, Meffre E, Difilippantonio M J, et al. Science. 2002;296:922–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1069398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baumann P, West S C. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paques F, Haber J E. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung P, Trujillo K M, Van Komen S. Mutat Res. 2000;451:257–275. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moens P B, Kolas N K, Tarsounas M, Marcon E, Cohen P E, Spyropoulos B. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1611–1622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caspari T, Murray J M, Carr A M. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1195–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.221402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiasa H, DiGate R J, Marians K J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2093–2099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szostak J W, Orr-Weaver T L, Rothstein R J, Stahl F W. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbertson L A, Stahl F W. Genetics. 1996;144:27–41. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundin O, Varshavsky A. Cell. 1981;25:659–669. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]