Abstract

Germ line mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 account for the increased risk of early onset of familial breast cancer, whereas overexpression of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases has been linked to the development of nonfamilial or sporadic breast cancer. To analyze whether there is a link between these two regulatory molecules, we studied the effects of ErbB-2 activation by heregulin (HRG) on BRCA1 function. It was previously demonstrated that HRG induced the phosphorylation of BRCA1, which was mediated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. Since altered interaction between cells and the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) is a common feature in a variety of tumors and since ECM modulates intracellular signaling, we hypothesized that ECM may affect the expression and HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1. Following stimulation by HRG, a strong increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation was observed in human T47D breast cancer cells seeded on plastic (PL). When T47D cells were seeded on laminin (LAM) or Matrigel, HRG induced a significantly higher proliferation than it did in cells seeded on PL. T47D cells seeded on poly-l-lysine had an abrogated mitogenic response, indicating the involvement of integrins in this process. HRG treatment induced a transient phosphorylation of BRCA1 that was enhanced in T47D cells grown on LAM. LAM-enhanced BRCA1 phosphorylation was mediated through α6 integrin upon HRG stimulation. Accordingly, T47D cells grown on LAM had the greatest increase in ErbB-2 activation, PI3K activity, and phosphorylation of Akt. A similar pattern of BRCA1 mRNA expression was observed when T47D cells were seeded on PL, LAM, or COL4. There was a significant decrease in the steady state of the BRCA1 mRNA level on both the LAM and COL4 matrices compared to that for cells seeded on PL. In addition, HRG stimulation caused a significant decrease in BRCA1 mRNA expression that was dependent on protein synthesis. Pretreatment with both the calpain inhibitor ALLN (N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal) and the proteosome inhibitor lactacystin inhibited the HRG-induced down-regulation of BRCA1 mRNA expression. Likewise, there was a strong decrease in the protein level of BRCA1 in T47D cells 4 h after treatment with HRG compared to its level in control nontreated T47D cells. Pretreatment with the proteosome inhibitors ALLN, lactacystin, and PSI [N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Ile-Glu-(O-t-butyl)-Ala-leucinal] inhibited also the HRG-induced down-regulation of BRCA1 protein in breast cancer cells. Interestingly, BRCA1 mRNA expression in HCC-1937 breast cancer cells, which express C-terminally truncated BRCA1, was not affected by either LAM or CL4. No phosphorylation of BRCA1 from HCC-1937 cells was observed in response to HRG. While Cdk4 phosphorylated wild-type BRCA1 in response to HRG in T47D cells, Cdk4 failed to phosphorylate the truncated form of BRCA1 in HCC-1937 cells. Furthermore, overexpression of wild-type BRCA1 in HCC-1937 cells resulted in the phosphorylation of BRCA1 and decreased BRCA1 expression upon HRG stimulation while overexpression of truncated BRCA1 in T47D cells resulted in a lack of BRCA1 phosphorylation and restoration of BRCA1 expression. These findings suggest that ECM enhances HRG-dependent BRCA1 phosphorylation and that ECM and HRG down-regulate BRCA1 expression in breast cancer cells. Furthermore, ECM suppresses BRCA1 expression through the C terminus of BRCA1.

BRCA1 is a tumor suppressor gene whose inactivation is associated with a high incidence of familial breast and ovarian cancers (5). Human BRCA1 encodes a 1,863-amino-acid nuclear phosphoprotein (58, 61). BRCA1 mRNA and protein levels are cell cycle regulated (74, 79) through the balance between proteolytic degradation and transcription (6). BRCA1 contains a RING finger domain at its amino terminus and two BRCT domains at its C terminus (35). BRCA1, alone (43) and together with BARD1 (28), promotes ubiquitin polymerization, while loss of BRCA1 ubiquitin protein ligase activity was linked to its radiation protection function (57).

BRCA1 was implicated as a caretaker gene, having a role in controlling recombination and genome integrity through association with Rad51 (62), and in the transcription-coupled repair of oxidative DNA damage (21). The C-terminal domain of BRCA1 has transcriptional activation activity and is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme via RNA helicase A (3, 50). BRCA1 was reported to be associated with proliferation (67), differentiation (44), and apoptosis (63).

BRCA1 protein is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage (41), in a cell cycle-dependent manner (58), after treatment with heregulin (HRG) (2), and after association with casein kinase 2 (51). While DNA damage-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 is elicited by ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (20) and by human Cds1 (hCds1) (39), its cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation is elicited through cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (56). BRCA1 contains four CDK consensus sites (56) and interacts with cyclin D (76) and CDK4 (76). The HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 was mediated at its nuclear translocation domain through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt-dependent pathway (2).

The basement membrane (BM), as a component of extracellular matrix (ECM), is composed of laminin (LAM), collagen type IV (COL4), and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (69). It interacts with cells through integrins and thereby regulates cell cycle progression, movement, survival, gene expression, and physical support (30). Integrins are heterodimeric proteins formed from α and β subunits, and each αβ combination confers a specific binding property to the cells (30). For instance, α6 and β1,4 are specific for LAM while α1,2,3 and β1,2 are specific for COL4 (42). Integrins functionally can modulate receptor tyrosine kinases. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor autophosphorylation is enhanced in a number of cell types, including fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and kidney epithelial cells, upon their interaction with ECM proteins (11, 32, 49). In ovarian and breast cancer cells, α6β4 integrin coimmunoprecipitated with ErbB-2. Ligation of this integrin increased ErbB-2 phosphorylation and invasion through the activated PI3K/Akt pathway (19). ECM, including the BM, through integrins (27), regulates numerous intracellular signaling molecules such as GTPases, cytoplasmic kinases, and growth receptor tyrosine kinases in breast cancer cells (30). In this regard, the cytoplasmic kinases, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and PI3K/Akt, were activated by the binding of LAM to either α6β1 or α6β4 integrin, respectively (64, 78). Furthermore, integrins play a major role in increasing cell tumorigenicity by stimulating the invasion of breast and ovarian cancer cells through PI3K and the activation of tyrosine kinases (19). In progressive breast cancer, an initial nontumorigenic cell phenotype is followed by the loss of BM-cell interactions (9), which is associated with ErbB-2 overexpression (59) and decreased BRCA1 expression (72). This leads to a phenotypic switch where cancer cells become tumorigenic, as manifested by their hyperproliferation and increased invasiveness (72). In the present study, we have elucidated the effects of the ECM on BRCA1 expression and its role in modulating HRG-dependent BRCA1 phosphorylation and expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Antibodies used for immunological analysis were as follows. Anti-BRCA1 antibody and antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10) were obtained from Genentech (San Francisco, Calif.). Phospho-Erk (E-4) antibody, anti-Erk-2 (C-154) antibody, anti-β4 integrin, anti-ErbB-2 (Neu) antibody, anti-Cdk4 antibody, monoclonal anti-BRCA1 antibody (D9), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Anti-Akt and anti-phospho-Ser-473 Akt antibodies were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY20) was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). Monoclonal antiactin antibody was from Chemicon (Temecula, Calif.). BRCA1 monoclonal antibodies N-129.5 and H-945.2 were kindly provided by Beckman Coulter, Inc. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody was from Becton Dickinson and PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.). Propidium iodide (PI), BrdU, MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide], Genestein, LY294002, actinomycin D, N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (ALLN), and phosphatidylinositol were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). PD98059, cycloheximide, and lactacystin were from Calbiochem-Novobiochem Co. (La Jolla, Calif.). EGF and myelin basic protein (MBP) were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, N.Y.), and HRG was from Genentech. [γ-32P]ATP, [α-32P]dCTP, and [3H]thymidine were from New England Nuclear (Boston, Mass.). Blocking anti-β1 integrin antibody was from the Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa), and blocking anti-α6 integrin antibody was a generous gift from Leslie Shaw (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass.). N-Benzyloxycarbonyl-Ile-Glu-(O-t-butyl)-Ala-leucinal (PSI) was from Sigma. All other chemicals were from Fisher Scientific (Norcross, Ga.) unless otherwise specified.

Cell culture.

T47D, MCF-7, and MDA-MB 231 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. These cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 3.5 μg of insulin/ml, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL), and penicillin-streptomycin. HCC-1937 breast cancer cells contain a truncated BRCA1 C-terminal and therefore express nonfunctional BRCA1 protein (8). These were cultured in Iscove's medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 15% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. To coat the plates, mouse LAM (20 μg/ml), human plasma fibronectin (FN; 30 μg/ml), COL4 (40 μg/ml), and Matrigel (MTR; Engelberth-Holm-Swarm tumor BM, 40 μg/ml; Becton Dickinson, Bedford, Mass.) were dissolved in sterile water, 0.05 M HCl, or cold medium, respectively; spread on culture dishes (1.0 ml/10-cm-diameter petri dish, 70 μl/well in 24-well plates); and allowed to dry in a sterile environment. COL1 solution (2.9 mg/ml) was purchased as Vitrogen-100 (Cohesion, Palo Alto, Calif.), added to the wells of the tissue culture plates (0.25 ml/well in 24-well plates), and then incubated for at least 60 min at 37°C to gel. Poly-l-lysine (POL; 40 μg/ml; Sigma) was dissolved in water spread on culture dishes (70 μl/ml in 24-well plates) and allowed to dry in a sterile environment. Quiescence was induced by replacing the growth medium of cells at 60 to 80% confluence with medium containing 0.4% FBS and then followed by 48-h incubation. To study the initiation of signaling, cells were stimulated with either HRG (20 nM), FBS (10%), EGF (10 ng/ml), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 1:1,000 dilution). To maintain cells in suspension, starved cells were detached by trypsinization, resuspended in 15 ml of growth medium, placed in an Erlenmeyer flask containing a stirring bar, and then placed in a humidified incubator for 30 to 45 min. For metabolic loading, subconfluent cultures of T47D cells grown on 100-mm-diameter coated or noncoated Corning tissue culture dishes were preincubated for 3 h at 37°C in RPMI 1640 phosphateless medium containing 100 μCi of carrier-free [32P]orthophosphate (HCl free)/ml before the addition of agonist.

Expression vectors.

C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (BrTrC) with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag was generated by PCR using BRCA1 cDNA as a template and the primers 5′-GGGGGATCCATGGATTTATCTGCTCTTCGCG-3′ (62) and 5′-CCTCGAGTTACTAGCAGAACATTTTGTTTCCT-3′. A BamHI-XhoI fragment of this product was subcloned into the same sites of the pCDNA3.1 vector containing the HA tag-coding sequence (36). The PCR-derived product was confirmed to be correct by direct sequencing. HA-tagged Cdk4 and the dominant-negative Cdk4 mutant (D158N) were kindly obtained from B. G. Gabrielli (Sydney, Australia) (18).

Transient transfections.

Constructs containing HA-tagged wild-type Cdk4, dominant-negative Cdk4 (D158N), C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (BrTrC), and wild-type BRCA1 were transfected in 293 T kidney cells and in T47D breast cancer cells by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested 24 or 48 h posttransfection, and overexpression of the constructs was assessed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies.

Cell attachment.

Cell attachment was performed as described previously (48). Briefly, labeled or unlabeled cells were released from petri dishes by trypsinization, resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1 mg/ml), and then seeded in 12-well plates that were either uncoated or precoated with ECM proteins. After 60 min, the percentage of attached cells was measured by the direct counting of attached and unattached cells with a Coulter counter or by scintillation counting of radiolabeled cells as described by Grinnell and Feld (22). The percent attachment was calculated as 100 × [cells attached/(cells attached + cells unattached)].

Mitogenic response.

Mitogenic response of T47D cells was performed as previously described (48). Briefly, cells were passaged at 105 cells/well (24-well plate) and grown either on plastic (PL), LAM, FN, COL1 or COL4, MTR, or POL-coated plates and starved to arrest cell growth. A mitogenic response in the quiescent cells was induced with HRG, FBS, or EGF and measured by [3H]thymidine (6.7 Ci/mM, 2 μCi/ml for 45 min) incorporation at different time points up to 30 h. After being labeled with [3H]thymidine, cells were washed three times with 5% trichloroacetic acid at 0°C and dissolved with 0.1 M NaOH and then radioactivity was measured by using a scintillation counter.

Cell cycle analysis.

T47D cells were seeded onto different matrices and synchronized for 48 h in growth medium containing 0.4% FBS. Cells were stimulated with either HRG (20 nM), NuSerum (10%), or EGF (10 ng/ml); loaded with BrdU (10 μg/ml) for 1 h, and harvested by trypsin-EDTA digestion after two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A total of 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/ml were fixed with 70% ice-cold methanol for at least 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min, cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of permeabilization solution (0.1 M HCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) and kept 30 min on ice. After two washes with ice-cold PBS, cells were heated for 5 min at 95°C in DNA denaturing solution (150 mM NaCl, 15 μM Na3O7C6H5), resuspended in antibody-diluting buffer (0.1% Triton X-100-1% BSA in PBS), and spun at 300 × g for 5 min. Cells were then labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody for 1 h and resuspended in PI staining solution (10 μg of PI/ml-0.1 mg of RNase A/ml in PBS). Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) at the Core Flow Cytometry Facility of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, Mass.). The percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle (G1, S, and G2/M) was calculated with ModFit LT cell cycle analysis software (Verity Software House).

Cdk4 in vitro kinase assay.

Cdk4 kinase assays were performed as described elsewhere (18, 45). Briefly, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM EGTA, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate) and cell lysates were precleared with a 50% suspension of protein A-Sepharose after sonication at 4°C. Cleared supernatants were incubated with either control antibody or anti-Cdk4 antibody for 2 to 3 h, precipitated with protein A-Sepharose, and washed three times with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT). The kinase assay was performed with the addition of 30 μl of kinase buffer containing either 1 to 3 μg of purified glutathione S-transferase-retinoblastoma (GST-Rb; kindly provided by J. Ladias, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass.) or 1 to 2 μg of immunoprecipitated BRCA1 in addition to 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and then were incubated for 30 min at 30°C. The reactions were stopped by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and run on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and phosphorylation was visualized by autoradiography.

RNA isolation and Northern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated using an RNA kit from Qiagen. The electrophoresis and blotting were done as described previously (47). Briefly, equal amounts of RNA (∼15 μg) were denatured, separated by electrophoresis on agarose-formaldehyde gels, and transferred to a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Membranes were hybridized with a 1,179-bp fragment corresponding to cDNA sequences from 1025 to 2222 of BRCA1 (that was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP). Levels of mRNA were normalized to 18S rRNA or to actin after probing the stripped blots with labeled rat cDNA to 18S rRNA or to actin. 32P labeling of probes was carried out with a random primer DNA labeling kit from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.). The cDNA fragment of BRCA1 was amplified by PCR as described by Gudas et al. (25), and the mouse 18S rRNA was kindly obtained from D. M. Templeton (University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

MAPK activity.

MAPK activity was determined by the ability of the immunoprecipitated enzyme to phosphorylate MBP (1) in an in vitro kinase assay. Immunoprecipitates were mixed with assay buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mg of MBP/ml, 100 mM ATP, and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of sample buffer for electrophoresis according to Laemmli (37), and the mixture was separated on SDS-15% PAGE gels for silver staining and autoradiography.

PI3K activity.

Cells were lysed in buffer A containing 137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and then cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY20). Precipitates were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay using [γ-32P]ATP and phosphatidylinositol as substrates according to the method of Derman et al. (12). Briefly, beads were washed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature in kinase buffer containing 0.5 mM ATP, 20 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 0.25 mg of phosphatidylinositol/ml, and 30 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol). Lipids were then extracted by CHCl3 · CH3OH (1:1) mixture and separated on oxalate-coated thin-layer chromatography plates (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.) in developing solution containing CHCl3 · CH3OH · H2O · NH4OH (60:47:11,3:2), followed by autoradiography.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer A, and lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE according to Laemmli (37). Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes in 25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine (pH 8.3) containing 15% methanol and then blocked with 5% BSA and 5% Carnation milk in 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 137 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, and 0.05% Tween 20. Membranes were then probed with either anti-Erk-2 antibody, polyclonal rabbit anti-phospho-Erk antibody, monoclonal mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10, monoclonal mouse anti-actin antibody, polyclonal rabbit anti-Akt antibody, polyclonal rabbit anti-phospho-Ser-473 Akt antibodies, or polyclonal anti-ErbB-2 antibody, and immunoreactive bands were detected with the NEN-Biolab (Boston, Mass.) enhanced chemiluminescence system, followed by autoradiography.

Cell viability.

Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate. After cells were treated with different inhibitors, 1 mg of MTT/ml in 100 μl of growth medium was added to each well and then cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The medium was removed, and 100 μl of DMSO was added. The cells were shaken for 30 min at room temperature, and optical density was measured at a dual wavelength of 490 and 650 nm on a DuPont multiwell spectrophotometer.

RESULTS

ECM modulates the HRG-dependent mitogenic response of T47D cells.

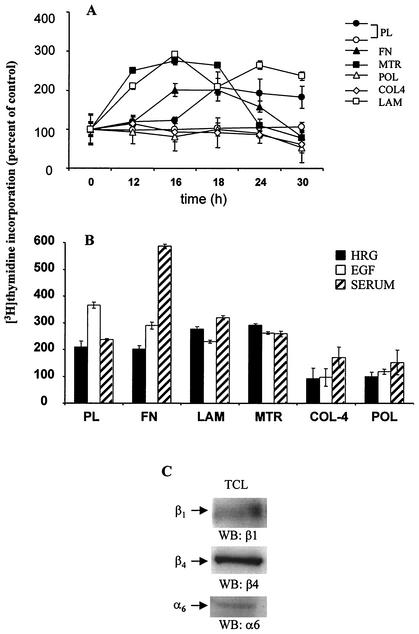

T47D breast cancer cells proliferate uniformly when treated with growth factors (34). To study the effect of substratum on the mitogenic response of T47D cells, the incorporation of [3H]thymidine and BrdU into DNA was measured. Cells grown on PL showed a maximal DNA synthesis between 12 and 20 h, peaking at 18 h after treatment with HRG (209% ± 22% versus 100% ± 38% of untreated cells [Fig. 1A ]). A similar response was obtained when T47D cells were grown on FN (206% ± 13% at 18 h). Cells seeded on COL4 strongly suppressed the mitogenic response (92% ± 38% at 18 h), whereas the peak of thymidine incorporation was markedly increased in those cells grown on LAM or MTR (276% ± 10% and 264% ± 11% at 18 h, respectively). Cells seeded on POL showed no difference in DNA synthesis whether in the presence or absence of HRG (100% ± 16% versus 100% ± 13%), suggesting the involvement of integrins, receptors for the ECM, in the HRG-dependent mitogenic response. Indeed, T47D breast cancer cells were found to express the α6, β1, and β4 integrins, as indicated in Fig. 1C. T47D cells adhered similarly to all substrata used in this study (PL, LAM, FN, COL4, and POL [data not shown]), suggesting that the differences in mitogenic response were not due to different numbers of cells attaching to different substrata. Thus, T47D cells proliferated to a comparable level when seeded on PL and FN while demonstrating decreased growth when seeded on COL4 or on POL. Cells grown on LAM or MTR demonstrated the highest mitogenic response upon treatment with HRG. Similar results were obtained with MCF-7 and MDA-MB 231 breast cancer cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of ECM on the HRG-dependent mitogenic response of T47D cells. (A) T47D cells were seeded on either 24-well PL plates (• and ○) or PL wells coated with FN, LAM, MTR, COL4, or POL and then starved for 48 h in medium containing 0.4% FBS. Cells were untreated (○) or treated with HRG (20 nM; •, ▴, □, ◊, and ▪) for the indicated times, and the medium was replaced with one that contained [3H]thymidine (2 μCi/ml). After 45 min, the “hot” medium was washed out, cells were lysed with NaOH, and cell remnants were collected into scintillation tubes to measure incorporated radioactivity. (B) To compare the effect of HRG with other growth factors, cells seeded as described for panel A were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) or FBS (10%). The representative level of thymidine incorporation (at the peak of DNA synthesis) was compared to that for nontreated cells (taken as 100%). Values are expressed as the means (%) ± standard deviations of quadruplicate wells from three separate experiments. (C) Total cell lysates (TCL) from T47D cells were processed for Western blotting (WB). Membranes were probed with anti-β1, anti-β4, or anti-α6 antibodies.

To determine if ECM would affect DNA synthesis elicited by other growth factors, we compared the mitogenic response of cells stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) (Fig. 1B, open bars) or FBS (10%) (Fig. 1B, striped bars) to that elicited by HRG (20 nM) (Fig. 1B, black filled bars). A representative time point of thymidine incorporation (at its peak at 18 h) was compared to that for nontreated cells (basal level, taken as 100% [data not shown]). Upon HRG treatment, cells seeded on LAM or MTR showed the strongest increase in DNA synthesis. Cells seeded on PL or FN as well as those grown on MTR had the greatest response to EGF (367% ± 11%, 290% ± 13%, and 262% ± 4%, respectively, versus 100% for nontreated cells [Fig. 1B]). Although cells grown on PL (237% ± 4%), LAM (320% ± 8%), or MTR (259% ± 9%) had a considerably high thymidine incorporation, those grown on FN had the highest peak of DNA synthesis after treatment with FBS (586% ± 8%). Interestingly, DNA synthesis was strongly suppressed on plates coated with POL (118% ± 10% at 18 h) or COL4 (97% ± 33% at 18 h) after treatment with EGF while cells treated with FBS responded modestly when seeded on these two matrices (POL, 152% ± 45%; COL4, 171% ± 39%; at 18 h). This modest effect could be attributed to the mixture of growth factors and cytokines found in FBS.

Similar results were obtained when BrdU incorporation and FACS assays were performed. As indicated in Table 1, T47D cells grown on COL4 or POL remained in the G1 phase of the cell cycle regardless of the stimulus: HRG, serum, or EGF. Cells grown on LAM entered S phase in the highest numbers after stimulation with HRG, while T47D cells entered S phase after treatment with serum or EGF when seeded on FN or PL, respectively. Thus, LAM and also LAM-containing MTR had the strongest effect in enhancing the HRG-dependent proliferation of T47D breast cancer cells. Similar data were obtained with MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

TABLE 1.

ECM alters the entry of T47D cells into mitosisa

| Type | HRG

|

Serum

|

EGF

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | S | G2/M | G1 | S | G2/M | G1 | S | G2/M | |

| PL-0 | 86.8 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 84.2 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 86.3 | 7 | 6.7 |

| PL | 74.4 | 15.9 | 9.7 | 72.1 | 15.4 | 12.5 | 67.8 | 15.7 | 16.5 |

| LAM | 66.7 | 20.9 | 12.4 | 63.6 | 22.7 | 13.7 | 75 | 14.9 | 10.1 |

| FN | 75.2 | 16.4 | 8.4 | 68.7 | 19.7 | 11.6 | 75.9 | 13.9 | 10.2 |

| COL4 | 81.7 | 7.5 | 10.8 | 76.9 | 9.2 | 13.9 | 79.4 | 9.1 | 11.5 |

| POL | 88.2 | 6 | 5.8 | 80.1 | 11.3 | 8.6 | 83 | 8.9 | 8.1 |

T47D cells were grown on PL, LAM, COL4, FN, or POL, and synchronized as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cells were left untreated (PL-0) or treated with HRG (20 nM), serum (NuSerum, 10%), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 18 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle (G1, S, and G2/M) was measured as indicated.

Cdk4 phosphorylates BRCA1 in an HRG-dependent manner.

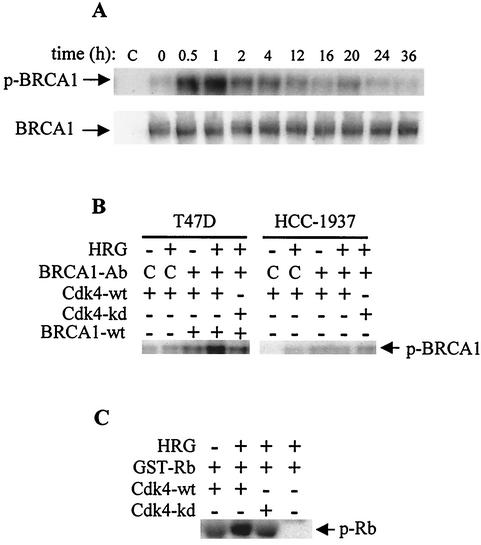

Previously, we reported that BRCA1 was phosphorylated upon stimulation of breast cancer cells with HRG (2). This observation was confirmed by the time course of BRCA1 phosphorylation in the present work. Cells were starved for 48 h, metabolically labeled with [32P]H3PO4, and then treated with HRG for the indicated times. The phosphorylation of BRCA1 was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-BRCA1 antibody, followed by separation of the precipitates on SDS-PAGE gels. Cells seeded on PL showed a transient phosphorylation of BRCA1 in response to HRG, peaking at 0.5 to 2 h and returning to the basal level thereafter (Fig. 2A). Next, we analyzed whether truncated C terminus BRCA1 is phosphorylated. HCC-1937 breast cancer cells, containing truncated BRCA1 at the C terminus, were analyzed for BRCA1 phosphorylation. Neither overexpression of constitutively active ErbB-2 in HCC-1937 cells nor stimulation with serum resulted in BRCA1 phosphorylation (data not shown). Since BRCA1 possesses four CDK consensus sites (56) and since HRG activates Cdk4 (40), we sought to determine whether this nuclear kinase mediates BRCA1 phosphorylation in response to HRG. We performed an in vitro kinase assay to determine whether Cdk4 phosphorylates BRCA1. To test this, wild-type Cdk4 cDNA and the kinase dead mutant Cdk4-D158N were transiently overexpressed in T47D cells. After 48 h, total cell lysates were prepared and subsequently immunoprecipitated with anti-Cdk4 antibodies or control antibodies following a 2-h stimulation with HRG. The immunoprecipitates were incubated with wild-type BRCA1 (from T47D cells [Fig. 2B, lanes 3 through 5]) or with C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (from HCC-1937 cells [lanes 8 through 10]) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction products were separated on SDS-PAGE before autoradiography. Only wild-type Cdk4 precipitated from the HRG-treated cells was able to phosphorylate BRCA1 (Fig. 2B, lane 4), while no phosphorylation was observed in the untreated cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 6), in cells expressing the kinase dead mutant (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 10), or in cells expressing C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (Fig. 2B, lanes 8 through 10). Similar to the untreated cells, the HRG-treated cells immunoprecipitated with the control anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 7) showed very low incorporation of radioactivity. As a control for the kinase assay, GST-Rb was used as a substrate (Fig. 2C). As expected, a low incorporation of radioactivity into substrate was observed in the reaction mixture containing the Cdk4 immunoprecipitates from the HRG-treated cells overexpressing the Cdk4-D158N construct (Cdk4-kd [Fig. 2C, lane 3]). However, Cdk4 immunoprecipitates from HRG-treated cells overexpressing wild-type Cdk4 showed a strong kinase activity, as indicated by the increased incorporation of [32P] into Rb (Fig. 2C, lane 2) compared to that for the HRG-untreated cells (Fig. 2C, lane 1). There was no detectable kinase activity in the reaction mixture containing GST-Rb and protein A-Sepharose only (Fig. 2C, lane 4). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that Cdk4 mediates the HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1.

FIG. 2.

Cdk4 phosphorylated BRCA1 at the C terminus in an HRG-dependent manner. (A) Cells were seeded on PL and starved for 48 h in growth medium containing 0.4% FBS. Four hours prior to stimulation with HRG (20 nM), cells were loaded with [32P]H3PO4. After stimulation for the indicated times, total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-BRCA1 antibody BRIN 129.5. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and incorporated radioactivity was visualized by autoradiography (upper gel). Immunoprecipitation assays were also subjected to Western blotting, and membranes were probed with BRIH monoclonal anti-BRCA1 antibody (lower gel). (B) Cdk4 in vitro kinase assay was performed with both BRCA1 proteins precipitated from T47D and HCC-1937 cells. To obtain a functional kinase, wild-type Cdk4 (Cdk4-wt) (lanes 1 through 4 and 6 through 9) and the kinase dead Cdk4-D158N mutant (Cdk4-kd) (lanes 5 and 10) were transiently overexpressed in T47D cells. After 48 h, T47D cells were fed with RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.2% FBS for overnight starvation. Cells were then stimulated with HRG lanes 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 10) for 2 h and harvested as indicated in Material and Methods. Cell lysates from T47D cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cdk4. In parallel, wild-type BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from T47D cells (lanes 3 through 5) and C-terminally truncated BRCA1 from HCC-1937 cells (lanes 8 through 10). The BRCA1 immunoprecipitates were used for the Cdk4 in vitro kinase reaction. C, reaction mixtures containing the immunoprecipitates obtained with the control antibody. (C) T47D cells overexpressing wild-type Cdk4 or kinase dead mutant were starved overnight and treated with HRG (lanes 2 through 4) or left untreated (lane 1). After 2 h of stimulation with HRG, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cdk4 antibody and the immunoprecipitates were then used in the in vitro kinase reaction to phosphorylate GST-Rb. The blots are representative of two independent experiments.

ECM modulates the HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1.

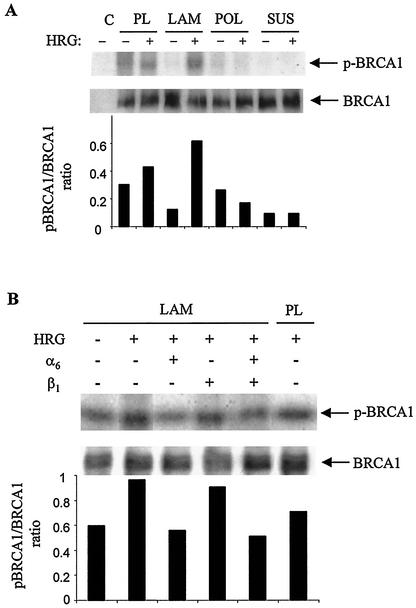

To investigate whether ECM may modulate BRCA1 phosphorylation, cells were grown on PL plates or on plates coated with either LAM or POL or were maintained in suspension. At the 1-h time point, representing the peak of HRG-dependent phosphorylation (Fig. 2A), the effect of ECM components on this process was tested. While the amount of BRCA1 protein was constant throughout the experiment, as indicated in the lower panels of Fig. 3, the level of phosphorylated BRCA1 upon HRG treatment was enhanced in cells seeded on LAM compared to that in those seeded on PL (Fig. 3A and B). The increased BRCA1 phosphorylation on LAM was suppressed by blocking antibodies for α6 integrin, while blocking anti-β1 integrin antibody had a modest effect, as indicated in Fig. 3B. Cells seeded on COL4 (data not shown) or those maintained in suspension showed no or very low phosphorylation of BRCA1. Taken together, these results indicate that LAM enhanced the HRG-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1. This phenomenon was mediated by α6 integrin.

FIG. 3.

ECM affects the HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1. (A) Cells seeded on PL, LAM, or POL or maintained in suspension (SUS) were starved, metabolically labeled with 32P, treated with HRG, and lysed as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2A. Immunoprecipitates were processed the same way as indicated above for the upper and lower gels. (B) Cells grown on LAM-coated plates or on PL were processed in the same way indicated above. Prior to stimulation with HRG, some plates coated with LAM were pretreated with blocking anti-α6 or blocking anti-β1 antibodies alone or together and processed as indicated above. The intensities of BRCA1 phosphorylation were normalized against the signal for total BRCA1 proteins and expressed as bar graphs. Autoradiographs are representative of two independent experiments.

Is HRG-dependent signaling enhanced in cells seeded on LAM?

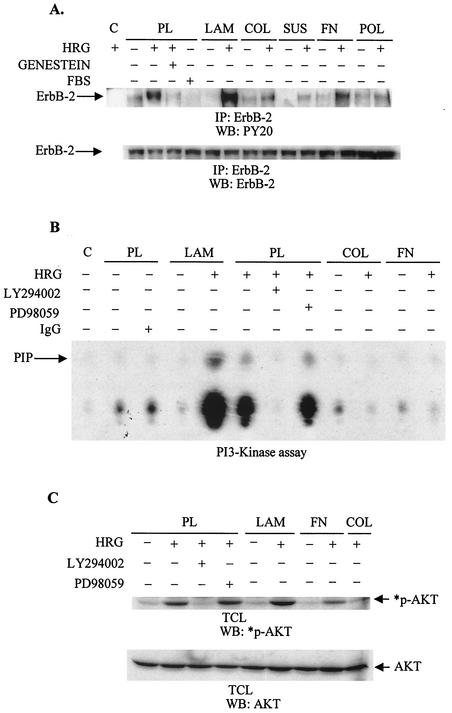

HRG-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 is regulated through the PI3K/Akt pathway after recruitment of PI3K to the activated receptor (2, 13). To investigate further the HRG-dependent intracellular signaling, cells were seeded on PL or on plates coated with FN, COL, or POL or were maintained in suspension and then compared to those grown on LAM. HRG increased the activity of various tyrosine kinases, which peaked at 10 min, as determined by antiphosphotyrosine antibody (data not shown). Therefore, the effect of ECM on HRG-dependent downstream signaling was tested at 10 min, the peak of tyrosine phosphorylation induced by HRG. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ErbB-2 antibody, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and probed with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Fig. 4A). Cells seeded on PL showed a strong increase in ErbB-2 tyrosine phosphorylation. This phosphorylation was two- and threefold stronger in cells grown on LAM, thereby corroborating the previous observations that LAM supported the strongest phosphorylation of BRCA1 and mitogenic response (Fig. 3A and B and 1A and B). Cells seeded on FN or COL4 showed stimulation of the ErbB-2 receptor; however, it was much lower than that seen in cells grown on PL. The lowest tyrosine phosphorylation was observed in cells seeded on POL or in cells maintained in suspension (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

LAM enhances the HRG-dependent activation of the ErbB-2 receptor and PI3K. (A) Starved T47D cells seeded on PL, LAM, COL4 (COL), FN, or POL or those maintained in suspension (SUS) were stimulated with HRG for 10 min. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-ErbB-2 monoclonal antibody, and then immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blotting (WB). Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were probed with 4G10 antibody (upper gel) or, after stripping, with an anti-ErbB-2 antibody (lower gel). Lane C, a sample of total cell lysates from stimulated cells grown on LAM that was immunoprecipitated with protein G-Sepharose only. Some cells were treated with Genestein (50 μg/ml) for 15 min prior to the 10-min treatment with HRG at the peak of tyrosine phosphorylation. As a comparison to the treatment with HRG, some cells were stimulated with FBS. (B) Starved cells seeded on PL, LAM, or COL4 (COL) or on FN-coated plates were treated with HRG (20 nM) for 10 min. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either antiphosphotyrosine antibody or normal mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) for the in vitro kinase assay (B) or processed for Western blotting (C). (B) Immunoprecipitates were tested for their ability to phosphorylate lipids in the presence of [γ32P]ATP. The phosphorylated lipids were then extracted from the reaction mixture by CHCl3 · CH3OH (1:1) and spotted on total cell lysate plates. The extracted, phosphorylated lipids were then separated in developing solution followed by autoradiography. PIP, phosphatidylinositol phosphate. (C) Immunoblots were probed with anti-p-Ser473 AKT antibody (*p-AKT) or with anti-AKT antibody (AKT) after stripping of the membrane. Some cells were pretreated with LY294002 (10 μM [panels B and C]) or with PD98059 (50 μM [panels B and C]). The autoradiograms are representative of two separate experiments. C, reaction mixture without cell lysates.

LAM increases HRG-dependent PI3 kinase activity but not MAPK activity.

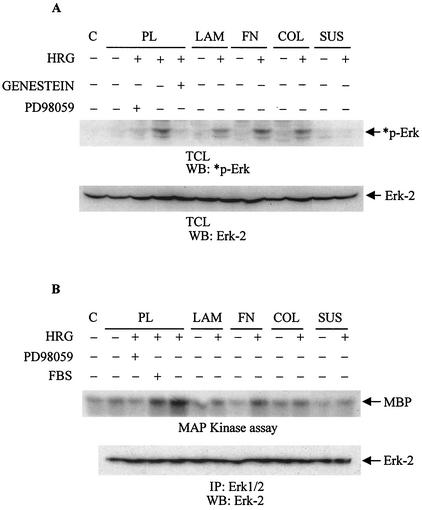

PI3K activity was measured by an in vitro kinase assay and by Western blotting with anti-phospho-Ser473 AKT antibodies. The highest degree of PI3K activity was observed in cells grown on LAM, and the lowest was seen on FN and COL4 (Fig. 4B and C). Samples from untreated cells were not able to significantly phosphorylate phospholipids. To address the specificity, several kinase inhibitors were used prior to the addition of HRG. As expected, LY294002 totally inhibited HRG-dependent PI3K activity in these cells while PD98059, a known MEK inhibitor, was not effective (Fig. 4B and C). MAPK did not play a significant role in this process, as determined by Western blotting with anti-phospho-MAPK antibodies and by an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). The strongest MAPK activity was observed in cells grown on PL or FN, while cells grown on COL4 or LAM or those maintained in suspension showed modest MAPK activity after treatment with HRG (Fig. 5A and B). Therefore, the greatest BRCA1 phosphorylation as seen in cells grown on LAM (Fig. 3A and B) also correlated with greater intracellular signaling on the same substratum (Fig. 4).

FIG. 5.

LAM does not enhance the HRG-dependent activation of MAPK. T47D cells were seeded on PL, LAM, FN, or COL4 (COL) or maintained in suspension (SUS). Starved cells were either left untreated or stimulated with HRG (20 nM) for 10 min. Obtained cytoplasmic cell lysates were either subjected to Western blotting (WB) (A) or immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Erk 1/2 antibody for the in vitro kinase assay (B). Some cells were treated with either PD98059 (50 μM) or Genestein (10 μM) prior to stimulation with HRG. (A) Blots of total cell lysates (TCL) were probed with anti-phospho-Erk-2 antibodies (*p-Erk), and then stripped and reprobed with anti-Erk-2 antibody as a control for total Erk protein (Erk-2). C, sample buffer plus RIPA buffer. (B) Immunoprecipitates were used for the in vitro kinase assay with [γ32P]ATP and MBP as a substrate. Control (C) indicates the basal level of the kinase activity. The lower panel represents immunoblots of immunoprecipitates probed with anti-Erk-2 antibody. Autoradiograms are representative of two independent experiments.

Effect of ECM on BRCA1 expression.

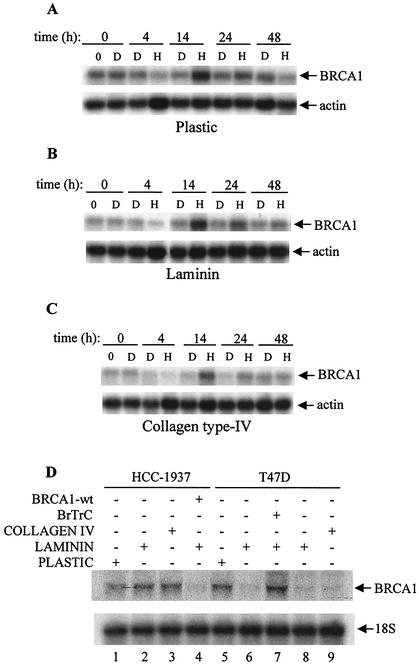

Because ECM affected the phosphorylation of BRCA1 in the presence of growth factors, we analyzed whether ECM also affects the expression of BRCA1. Over an extended time course, we observed a biphasic effect of HRG on BRCA1 mRNA levels in T47D cells grown on PL. Specifically, we noted a high basal level of BRCA1 mRNA in nontreated cells which decreased rapidly up to 4 h after HRG treatment. This was followed by an increase in BRCA1 mRNA, peaking at 12 to 16 h, and by a decrease thereafter which approached the basal level (data not shown). Based on these initial observations, we decided to compare the effect of ECM components on the expression of BRCA1 in nontreated or HRG-treated cells. The five most characteristic times, including 0, 4, 14, 24, and 48 h after treatment with HRG, were taken as study points and then compared to those time points after treatment with DMSO (Fig. 6A through C). A characteristic biphasic pattern of BRCA1 expression after the treatment with HRG was observed in cells grown on PL, LAM, or COL4. However, there was lower expression of BRCA1 in cells grown on LAM and the lowest expression in cells grown on COL4 (Fig. 6A through C). The decreased BRCA1 mRNA levels in T47D cells observed on either LAM (Fig. 6D, lanes 6 and 8) or COL4 (Fig. 6D, lane 9) were not observed in HCC-1937 breast cancer cells (Fig. 6D, lanes 1 through 3). However, when C-terminally truncated BRCA1 was overexpressed in T47D cells grown on LAM, BRCA1 expression was restored (Fig. 6D, lane 7), while the control vector had no effect (Fig. 6D, lane 8). In addition, when wild-type BRCA1 was overexpressed in HCC-1937 cells grown on LAM (Fig. 6D, lane 5), the decrease in BRCA1 mRNA was observed again. This result suggests that this phenomenon was mediated through the C terminus of the BRCA1 molecule, as HCC-1937 cells express C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (8).

FIG. 6.

Effect of HRG and/or ECM on BRCA1 mRNA expression in T47D and HCC-1937 cells. Cells were seeded on PL (A) or on plates coated with LAM (B) or COL4 (C) and then starved for 48 h. Cells were next treated with HRG (H, 20 nM) or DMSO (D, 1:1,000 dilution). At the indicated times, total RNA was collected by using a Qiagen kit and 20 μg of the total RNA was subjected to Northern blotting. (D) HCC-1937 and T47D cells were seeded on PL (lanes 1 and 5), LAM (lanes 2, 4, and 6 through 8), or COL4 (lanes 3 and 9) and starved for 48 h as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2A. C-terminally truncated BRCA1 (BrTrC) construct (lane 7) or empty vector (lane 8) was overexpressed into T47D cells grown on LAM, and wild-type BRCA1 (BRCA1-wt) was overexpressed in HCC-1937 cells grown also on LAM (lane 4) for 48 h. Total RNA was collected and processed the same way as described above. Blots in panels A through D were probed with a 1,179-bp fragment of BRCA1 (upper gels) and with actin cDNA or 18S rRNA as indicated (lower gels). Results are representative of two or three independent experiments.

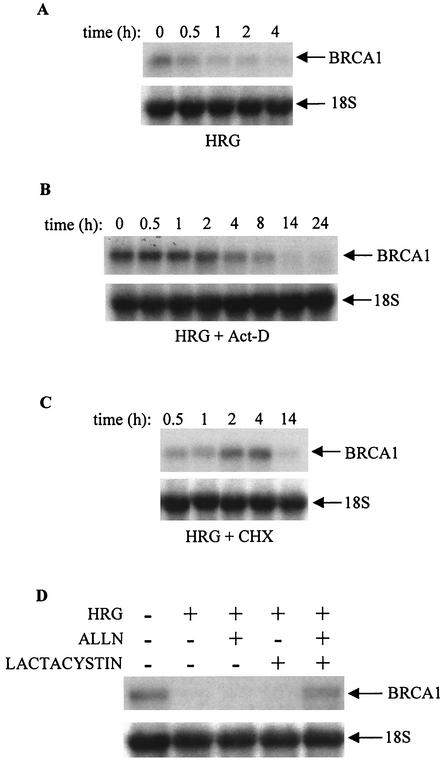

In order to test whether this strong decrease in BRCA1 mRNA expression upon HRG treatment is dependent on protein synthesis or the stability of the mRNA, cells were treated with actinomycin D or with cycloheximide. There was no difference in the BRCA1 mRNA pattern when cells were treated with HRG alone (Fig. 7A) or HRG together with actinomycin D (Fig. 7B). However, treatment of cells with cycloheximide (Fig. 7C) reversed the effect of HRG, as the mRNA expression of BRCA1 was increased 2 and 4 h after addition of the growth factor. This suggests the dependence of this phenomenon on protein synthesis. To further elucidate the decrease in BRCA1 mRNA level 4 h after treatment with HRG, cells were also treated with ALLN (a calpain inhibitor) or lactacystin (a proteosome inhibitor) prior to the addition of HRG. As indicated in Fig. 7D, the HRG-dependent decrease in the BRCA1 mRNA level was not affected by pretreatment of cells with ALLN or lactacystin alone, while both inhibitors combined overcame the effect of HRG. In addition, another proteosome inhibitor, PSI, had an effect on the HRG-dependent BRCA1 mRNA level compared to that of ALLN and lactacystin together (data not shown). To test whether these inhibitors would affect cell viability, we performed an MTT assay under the same experimental conditions. Under most conditions, 90 to 100% of the cells were viable.

FIG. 7.

Effect of various inhibitors on the level of BRCA1 mRNA in T47D breast cancer cells. T47D cells were seeded on PL plates (A through D) and starved in growth medium containing 0.4% FBS. After 48 h, cells were either untreated (0) or treated with HRG alone (A) or with HRG in the presence of actinomycin D (B) or cycloheximide (C) for the indicated times. Some cells were also treated with ALLN or lactacystin, alone or in combination, prior to the treatment with HRG for 4 h (D). Total RNA was extracted and processed the same way as indicated in the legend to Fig. 6. Autoradiograms are representative of two independent experiments.

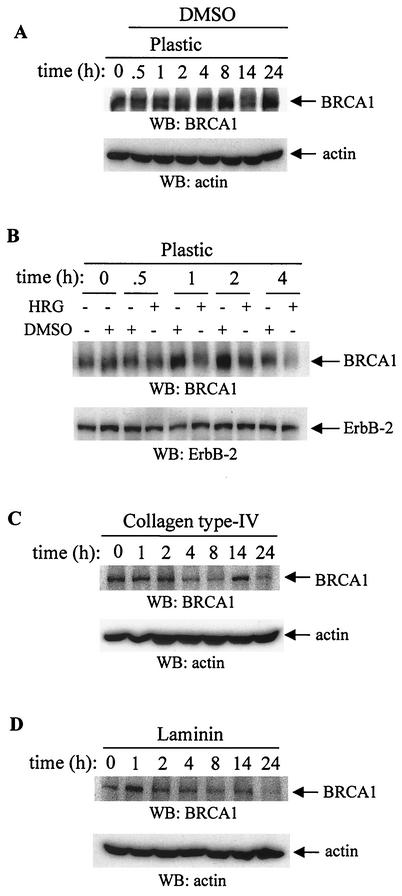

Effect of ECM and HRG on BRCA1 protein levels in T47D cells.

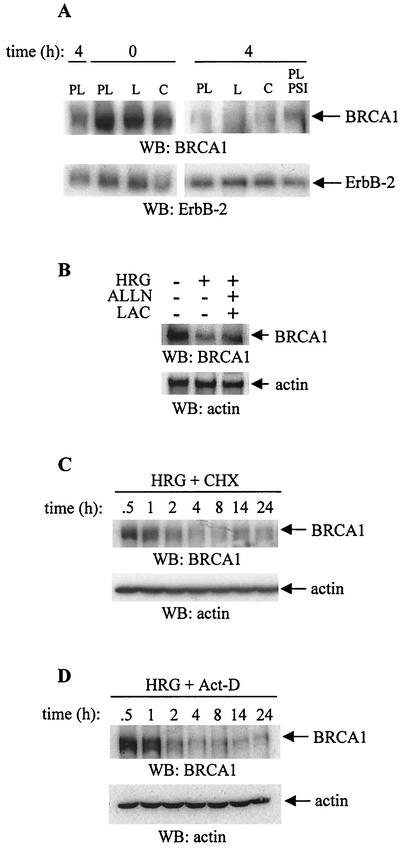

The strong basal level (Fig. 8A) of BRCA1 protein was decreased 4 h after treatment with HRG (Fig. 8B and 9A). Treatment of cells with DMSO, a solvent for HRG, did not decrease the level of BRCA1 protein (Fig. 8A and B). Cells were also seeded onto COL4 and LAM to test whether these matrices would affect protein expression as they affected the BRCA1 mRNA. Untreated cells grown on LAM had a lower level of BRCA1 protein than those grown on collagen IV or on PL (Fig. 8A through D). Similar to the cells adhering to PL, there was a decrease in BRCA1 protein level 4 h after stimulation with HRG, and this level further decreased up to 14 to 24 h (Fig. 8C and D). The protein loading did not affect the results as the membranes were stripped and reprobed with either antiactin antibody or with anti-ErbB-2 antibody (Fig. 8A through D, lower panels). Similar to the expression of mRNA, the low BRCA1 protein level 4 h after treatment with HRG was restored after pretreatment with proteosome inhibitors such as ALLN, lactacystin, and PSI, (Fig. 9A and B), suggesting the involvement of proteosome in this process. Four-hour exposure of T47D cells to cycloheximide or to actinomycin D, together with HRG, down-regulated BRCA1 protein to undetectable levels (Fig. 9C and D), an effect similar to that observed when cells were treated with HRG alone (Fig. 9A). These results also suggest the involvement of both processes, protein synthesis and the stability of mRNA, in the suppressive effect of HRG on BRCA1 protein expression in these cells.

FIG. 8.

Effect of HRG, ECM, and various inhibitors on BRCA1 protein level. T47D cells seeded on PL-, COL4-, or LAM-coated plates were starved and treated with HRG (20 nM) (B through D) or with DMSO (A and B) as a control for the indicated times. (A) Total cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blotting (WB). Membranes were probed with anti-BRCA1 antibody (upper gel) or, after stripping, with antiactin antibody (lower gel). (B) After cells were treated with HRG or DMSO, total cell lysates were collected at the indicated times and subjected to Western blotting. Membranes were probed with anti-BRCA1 antibody (upper gel) or, after stripping, with anti-ErbB-2 antibody (lower gel). (C and D) T47D cells were seeded on COL4 (C, 20 μg/ml)- or LAM (D, 20 μg/ml)-coated plates, starved, and then stimulated with HRG for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were processed the same way as indicated in the legend to Fig. 8B. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with antiactin antibodies. The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

FIG. 9.

Effect of various inhibitors on BRCA1 protein level. (A) Cells seeded on LAM (L) or COL4 (C) or on PL were treated with HRG for the indicated times. Some cells grown on PL were pre-treated with PSI before the addition of HRG. Total cell lysates were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 8A. (B) T47D cells were seeded on PL plates and starved in growth medium containing 0.4% FBS. After 48 h, cells were either untreated or treated with HRG alone or with HRG in the presence of ALLN and lactacystin (LAC) together. (C) Starved T47D cells seeded on PL were treated with HRG in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times, and total cell lysates were analyzed. (D) Cells were treated with HRG and actinomycin D (Act-D). Upper gels show the level of BRCA1 protein probed with the anti-BRCA1 antibody. The lower panels indicate the level of ErbB-2 (A) or actin (B through D) after reprobing the membranes with the corresponding antibodies. The blots of all panels are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

An altered interaction between cells and surrounding ECM is a common feature of a variety of tumors (77). In breast cancer, either epithelial cells are incapable of producing an organized BM, which would normally induce growth arrest, or malignant cells fail to recognize their ECM because of expression of inappropriate or nonfunctional integrins (77). Conversely, it is possible to restore normal cellular differentiated function by correcting cell-ECM interactions (10, 29, 68, 77). Furthermore, integrins, including α6β4, can regulate intracellular signaling cascades such as MAPK and PI3K (64, 78). Given that the level of BRCA1 is significantly lower in invasive breast cancer than that found in normal breast epithelial tissue (72) and that BRCA1 is phosphorylated in an HRG-dependent manner via the PI3K pathway (2), we postulated that ECM could affect the expression and phosphorylation of this tumor suppressor gene. Therefore, the effects of BM components such as LAM and COL4 on BRCA1 expression and phosphorylation were studied. We observed that both HRG and ECM affected the expression and phosphorylation of BRCA1. HRG-dependent proliferation of T47D cells was highest in cells seeded on LAM or on LAM containing MTR, while the greatest mitogenic response to EGF or FBS was seen in cells seeded on PL or FN, respectively. The phosphorylation of BRCA1, which was mediated through Cdk4 and α6 integrin, was highest in cells seeded on LAM compared with cells seeded on PL or POL or to those maintained in suspension. Likewise, HRG-dependent intracellular signaling, which leads to BRCA1 phosphorylation, such as that through the PI3K/Akt pathway, was also enhanced in cells grown on LAM. We also found strong suppressive effects of both LAM and COL4 on the mRNA level of BRCA1, which were mediated through its C terminus. Treatment with HRG caused a biphasic response of BRCA1 mRNA expression in cells seeded on all three substrata (PL, LAM, and COL4), an initial decrease peaking 4 h after treatment followed by a strong increase peaking at 14 h. The strong decrease in BRCA1 expression 4 h after treatment with HRG was mediated through protein degradation.

Stimulation of T47D breast cancer cells with HRG induced cell cycle progression with the peak of DNA synthesis between 16 and 20 h. In a similar, proliferation-linked fashion, BRCA1 mRNA expression was observed on all three matrices tested in the present work. This pattern of BRCA1 expression resembles those reported earlier in T47D cells (26), MCF-7 cells (26, 74), and normal epithelial cells (24, 44, 52, 54, 74). The significantly lower BRCA1 mRNA level observed in cells grown on LAM or on COL4 suggests that BM components possess a mechanism that down-regulates BRCA1 mRNA. This response could be induced through integrins expressed in T47D cells. Indeed, T47D cell proliferation was blocked in cells grown on POL (Fig. 1 and Table 1) and BRCA1 phosphorylation was suppressed by blocking anti-α6-integrin antibodies (Fig. 3B). The strong effect of COL4 on BRCA1 mRNA levels implicates β1, α1, and α2 integrins (collagen receptors) in addition to α6β4 (LAM receptor). Recently, it was implied that the MTR matrix suppressed the expression of BRCA1 in normal breast epithelial cells (52). These authors attributed this suppressive effect of MTR to LAM. However, in our study, we found that COL4 was clearly the most potent in suppressing BRCA1 mRNA expression. Thus, it will be of interest to examine whether heparan sulfate proteoglycans, entactin, nidogen, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), as components of MTR matrix (33), participate in such effects.

ECM-dependent BRCA1 mRNA down-regulation was mediated through the C terminus of the BRCA1 molecule. The level of BRCA1 mRNA was not significantly affected by the plating of HCC-1937 breast cancer cells on either LAM- or COL4-coated plates. These cells contain C-terminally truncated BRCA1 protein due to a gene mutation after codon 1755 (73). This region encompasses one BRCT domain and touches the second BRCT domain of the BRCA1 molecule, thereby disrupting their function (57). The BRCT domain is defined by a distinct cluster of 95 amino acids and is involved in protein-protein interactions (7). Recently, it was shown that activated SMAD2 bound to the Swift protein through the BRCT domain and elicited TGF-β1-induced gene regulation (65). Therefore, it is possible that the TGF-β1-dependent down-regulation of BRCA1 (60) in cells containing wild-type BRCA1 is absent in HCC-1937 breast cancer cells, as the BRCA1 in these cell lacks the BRCT domain necessary for binding activated SMAD2.

The strong decrease in BRCA1 protein and mRNA expression 4 h after stimulation with HRG suggests that this time point may be important in the regulation of BRCA1 expression because it occurred just before G1/S boundary elevation of the BRCA1 mRNA. Treatment of cells with general inhibitors such as actinomycin D and cycloheximide (Fig. 7B and C) suggests that this phenomenon was dependent on protein synthesis. Experiments with more specific inhibitors, such as ALLN and/or lactacystin, implicated the requirement of both calpain and proteosome in this process. Interestingly, neither ALLN nor lactacystin alone had a significant effect on BRCA1 mRNA expression. This result is similar to those of Blagosklonny et al. (6), who reported that ALLN treatment did not affect BRCA1 mRNA levels in the cell lines they had tested. Both proteases, calpain and proteosome, could be activated under our experimental conditions. On the one hand, calpain is activated in response to the [Ca2+] elevation (80) initiated by integrin-ECM interactions (16, 55). In this regard, β1 integrin was shown to be involved in initiating [Ca2+]-dependent pathways (66). On the other hand, proteosome could be activated by the phosphorylation of target proteins such as that achieved after stimulation with HRG in the present work. Thus, it is possible that cell attachment on LAM caused the activation of proteosome through the phosphorylation of BRCA1, while attachment on COL4 activated calpain through β1 integrin, each causing a decrease in BRCA1 mRNA expression.

A significant reversal of the HRG-dependent decrease in BRCA1 protein levels 4 h after treatment with PSI or lactacystin with ALLN suggests the involvement of proteosome-dependent protein degradation. The BRCA1 molecule contains a RING finger motif at its N terminus (46, 57) that was linked to the activation of ubiquitin ligase activity (31, 57). Recent reports demonstrated that BRCA1 promotes ubiquitin polymerization by itself (43) and in concert with another RING finger-containing protein, BARD1 (28). Ruffner et al. showed that mutations in the RING finger domain abolished the ubiquitin ligase activity of BRCA1, thereby linking this activity of BRCA1 to its γ-radiation protection function (57). Phosphorylated BRCA1 could become a target of ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, as a number of substrates are known to require phosphorylation prior to ubiquitination. For instance, IκBα as a target protein is recognized by the SCF complex after being phosphorylated at Ser32 and Ser36 (17). The SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase system mediates the ubiquitination of many cellular proteins. SCF is named for three of its core components: p19skp1, CDC53/cullin, and F-box-containing protein. However, so far, there has been no link shown between the ubiquitination of BRCA1 and its degradation. Recently, it was shown that p53, another tumor suppressor gene, was targeted, ubiquitinated, and subsequently degraded upon activation of the Her/Neu signaling cascade (81). Similarly, as shown in our experiments, Zhou et al. reported that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway was activated, thereby producing MDM2 phosphorylation, nuclear localization, and association with CBP/p300 (81). As CBP/p300 also interacts with BRCA1 (53), it is possible that CBP/p300 provides a platform for the assembly of the protein complex which is necessary for the MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of BRCA1 (23). Our results corroborate those of Blagosklonny et al., who reported that BRCA1 levels are regulated by protein degradation in cancer cell lines with a low steady state of BRCA1 protein (6). They indicated specifically that the cathepsin-like protease degradation of BRCA1 was in balance with BRCA1 transcription. However, our results differ from those of Aprelikova et al., who reported no change in BRCA1 protein level in starved MCF-10A cells or in MCF-10A cells stimulated with EGF (4). This difference could be attributed to the use of different techniques or cell lines.

The data reported here are consistent with the idea that growth factors and integrins can synergize to mediate biological processes and that such collaborative action requires integrin aggregation and receptor occupancy (49, 70, 75). Similarly, the increased phosphorylation of BRCA1 on LAM was mediated through α6 integrin, while in the same cells, ErbB-2 along with PI3K showed enhanced activity. Our results support the findings of Falcioni et al., who showed that the increased DNA synthesis observed in carcinoma cells treated with α6-integrin ligand was mediated through elevated ErbB-2 phosphorylation (14). β4 integrin is most likely also involved in this process, as Gambaletta et al. reported that expression of both α6β4 integrin and ErbB-2 was required for the activation of PI3K. The authors further identified a specific region within the cytoplasmic domain of β4 that was essential for cell invasion (19). The α6β4 and α6β1 integrins, but not the α5β1, α3β1, and α2β1 integrins, associate with and activate ErbB-2 receptors as demonstrated by coprecipitation of cell lysates from human carcinoma cell lines (14). This association was shown to be meaningful as α6β4 integrins together with ErbB-2 were able to activate PI3K and thereby promote cell invasion (19) and proliferation (14). Along with the synergism between growth factors and integrins, it seems that different growth factors cooperate with different sets of integrins in order to regulate oncogenic pathways. For instance, in the present work, while the strongest proliferation in response to HRG was observed in cells grown on LAM, the maximal mitogenic response upon EGF or FBS treatment was achieved in cells seeded on PL or FN, respectively. While the strong inhibitory effect of POL on cell proliferation indicates integrin involvement in this process, the effect of COL4 is somewhat surprising. Cells grown on COL4 had suppressed proliferation, accompanied by decreased BRCA1 expression, and suppressed HRG-dependent phosphorylation, while cells seeded on LAM showed decreased BRCA1 expression, as well as increased HRG-dependent phosphorylation and cell proliferation. One possibility is that cells adhering to COL4 enhanced the expression and activation of β1C integrin, which in turn could inhibit the proliferation of both tumorigenic and nontumorigenic cells by increasing expression of p27kip1 (15). It would be interesting to see whether these cells seeded on COL4 have enhanced the expression of β1C integrin and this CDK inhibitor.

BRCA1 can be phosphorylated in a cell cycle- (58) and DNA damage-dependent (61, 71) manner. Phosphorylation of BRCA1, as we indicated earlier, could also occur at the region spanning the nuclear translocation sequence after cell stimulation with HRG. This phosphorylation was regulated through a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway (2). In addition, as shown here, Cdk4 phosphorylated BRCA1 in response to HRG. BRCA1 possesses four CDK consensus sites and was shown to be phosphorylated by CDK2 (56). The peak of HRG-dependent BRCA1 phosphorylation (between 0.5 and 2 h) indicates it may be mediated through a CDK that is active earlier in the cell cycle, such as CDK4 or CDK6. Indeed, HRG activates both CDK6 (38) and CDK4 (40) and BRCA1 interacts with cyclin D (76), suggesting that BRCA1 could be phosphorylated with a cyclin D associated kinase. Although Ruffner et al. demonstrated that, in an in vitro assay, CDK6 could weakly phosphorylate BRCA1 protein (56), CDK6 involvement in this process seems unlikely. Only CDK4, not CDK6, could be coimmunoprecipitated with BRCA1 (76).

In summary, we showed that both HRG and ECM could affect the expression and phosphorylation of BRCA1. HRG induced BRCA1 phosphorylation through Cdk4 and induced a strong decrease in BRCA1 mRNA and protein level through protein degradation. LAM enhanced HRG-dependent BRCA1 phosphorylation, which resulted in increased cell proliferation, whereas both LAM and COL4 caused a C-terminally dependent decrease in BRCA1 mRNA expression. However, COL4 suppressed the HRG-dependent mitogenic response in these cells. The linkage between HRG-dependent phosphorylation and the decreased BRCA1 expression on the one side and between BRCA1 and integrin expression on the other remains to be determined in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hyong-Tae Kim and Alfred Goldberg (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.) for their help and advice on the methods for BRCA1 degradation studies; John Ladias (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass.) for providing the GST-Rb construct; Brian G. Gabrielli (University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) and Ed Harlow (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass.) for providing the Cdk4 constructs; Istok Miralem for technical help; Janet Delahanty for editing of the manuscript, and Dan Kelley and Jasmila Miralem for help in preparation of the figures.

This study was supported by NIH grants CA 76226 and R21CA87290 (H.K.A.); by Department of the Army grants DAMD 17-1-0152 (T.M.), DAMD 17-98-1-8032, and DAMD 17-99-1-9078; by the Experienced Breast Cancer Research grant 34080057089; by the Milheim Foundation; and by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (H.K.A.). This work was done during the tenure of an established investigatorship from the American Heart Association (H.K.A.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, N. G., J. E. Weiel, C. P. Chan, and E. G. Krebs. 1990. Identification of multiple epidermal growth factor-stimulated protein serine/threonine kinases from Swiss 3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11487-11494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altiok, S., D. Batt, N. Altiok, A. Papautsky, J. Downward, T. M. Roberts, and H. Avraham. 1999. Heregulin induces phosphorylation of BRCA1 through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32274-32278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, S. F., B. P. Schlegel, T. Nakajima, E. S. Wolpin, and J. D. Parvin. 1998. BRCA1 protein is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex via RNA helicase A. Nat. Genet. 19:254-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aprelikova, O., A. Kuthiala, M. Bessho, S. Ethier, and E. T. Liu. 1996. BRCA1 protein level is not affected by peptide growth factors in MCF10A cell line. Oncogene 13:2487-2491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwood, M. A., and B. L. Weber. 1998. BRCA1 and BRCA2: from molecular genetics to clinical medicine. J. Clin. Oncol. 16:1969-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blagosklonny, M. V., W. G. An, G. Melillo, P. Nguyen, J. B. Trepel, and L. M. Neckers. 1999. Regulation of BRCA1 by protein degradation. Oncogene 18:6460-6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callebaut, I., and J. P. Mornon. 1997. From BRCA1 to RAP1: a widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 400:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J., D. P. Silver, D. Walpita, S. B. Cantor, A. F. Gazdar, G. Tomlinson, F. J. Couch, B. L. Weber, T. Ashley, D. M. Livingston, and R. Scully. 1998. Stable interaction between the products of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes in mitotic and meiotic cells. Mol. Cell 2:317-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrenek, M. A., P. Wong, and V. M. Weaver. 2001. Tumour-stromal interactions. Integrins and cell adhesions as modulators of mammary cell survival and transformation. Breast Cancer Res. 3:224-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke, A. S., M. M. Lotz, C. Chao, and A. M. Mercurio. 1995. Activation of the p21 pathway of growth arrest and apoptosis by the beta 4 integrin cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22673-22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cybulsky, A. V., A. J. McTavish, and M. D. Cyr. 1994. Extracellular matrix modulates epidermal growth factor receptor activation in rat glomerular epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 94:68-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derman, M. P., J. Y. Chen, K. C. Spokes, Z. Songyang, and L. G. Cantley. 1996. An 11-amino acid sequence from c-met initiates epithelial chemotaxis via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 271:4251-4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downward, J. 1998. Lipid-regulated kinases: some common themes at last. Science 279:673-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falcioni, R., A. Antonini, P. Nisticò, S. Di Stefano, M. Crescenzi, P. G. Natali, and A. Sacchi. 1997. α6β4 and α6β1 integrins associate with ErbB-2 in human carcinoma cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 236:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornaro, M., M. Manzotti, G. Tallini, A. E. Slear, S. Bosari, E. Ruoslahti, and L. R. Languino. 1998. β1C integrin in epithelial cells correlates with a nonproliferative phenotype: forced expression of β1C inhibits prostate epithelial cell proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 153:1079-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox, J. E., R. G. Taylor, M. Taffarel, J. K. Boyles, and D. E. Goll. 1993. Evidence that activation of platelet calpain is induced as a consequence of binding of adhesive ligand to the integrin, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa. J. Cell. Biol. 120:1501-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs, S. Y., A. Chen, Y. Xiong, Z.-Q. Pan, and Z. Ronai. 1999. HOS, a human homolog of Slimb, forms an SCF complex with Skp1 and Cullin1 and targets the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of IκB and β-catenin. Oncogene 18:2039-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrielli, B. G., B. Sarcevic, J. Sinnamon, G. Walker, M. Castellano, X. Q. Wang, and K. A. Ellem. 1999. A cyclin D-Cdk4 activity required for G2 phase cell cycle progression is inhibited in ultraviolet radiation-induced G2 phase delay. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13961-13969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gambaletta, D., A. Marchetti, L. Benedetti, A. M. Mercurio, A. Sacchi, and R. Falcioni. 2000. Cooperative signaling between α6β4 integrin and ErbB-2 receptor is required to promote phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10604-10610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatei, M., B. B. Zhou, K. Hobson, S. Scott, D. Young, and K. K. Khanna. 2001. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase and ATM and Rad3 related kinase mediate phosphorylation of Brca1 at distinct and overlapping sites. In vivo assessment using phospho-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17276-17280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowen, L. C., A. V. Avrutskaya, A. M. Latour, B. H. Koller, and S. A. Leadon. 1998. BRCA1 required for transcription-coupled repair of oxidative DNA damage. Science 281:1009-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grinnell, F., and M. K. Feld. 1979. Initial adhesion of human fibroblasts in serum-free medium: possible role of secreted fibronectin. Cell 17:117-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman, S. R., M. Perez, A. L. Kung, M. Joseph, C. Mansur, Z. X. Xiao, S. Kumar, P. M. Howley, and D. M. Livingston. 1998. p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation. Mol. Cell 2:405-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gudas, J. M., T. Li, H. Nguyen, D. Jensen, F. J. Rauscher III, and K. H. Cowan. 1996. Cell cycle regulation of BRCA1 messenger RNA in human breast epithelial cells. Cell Growth Differ. 7:717-723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gudas, J. M., H. Nguyen, R. C. Klein, D. Katayose, P. Seth, and K. H. Cowan. 1995. Differential expression of multiple MDM2 messenger RNAs and proteins in normal and tumorigenic breast epithelial cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 1:71-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gudas, J. M., H. Nguyen, T. Li, and K. H. Cowan. 1995. Hormone-dependent regulation of BRCA1 in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 55:4561-4565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gui, G. P., C. A. Wells, P. D. Browne, P. Yeomans, S. Jordan, J. R. Puddefoot, G. P. Vinson, and R. Carpenter. 1995. Integrin expression in primary breast cancer and its relation to axillary nodal status. Surgery 117:102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashizume, R., M. Fukuda, I. Maeda, H. Nishikawa, D. Oyake, Y. Yabuki, H. Ogata, and T. Ohta. 2001. The RING heterodimer BRCA1-BARD1 is a ubiquitin ligase inactivated by a breast cancer-derived mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14537-14540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlett, A. R., N. Bailey, C. Damsky, O. W. Petersen, and M. J. Bissell. 1995. Cellular growth and survival are mediated by beta 1 integrins in normal human breast epithelium but not in breast carcinoma. J. Cell Sci. 108:1945-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hynes, R. O. 1999. Cell adhesion: old and new questions. Trends Cell Biol. 9:M33-M37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joazeiro, C. A., S. S. Wing, H. Huang, J. D. Leverson, T. Hunter, and Y. C. Liu. 1999. The tyrosine kinase negative regulator c-Cbl as a RING-type, E2-dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase. Science 286:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones, P. L., J. Crack, and M. Rabinovitch. 1997. Regulation of tenascin-C, a vascular smooth muscle cell survival factor that interacts with the αvβ3 integrin to promote epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and growth. J. Cell. Biol. 139:279-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinman, H. K., M. L. McGarvey, L. A. Liotta, P. G. Robey, K. Tryggvason, and G. R. Martin. 1982. Isolation and characterization of type IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry 21:6188-6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodali, S., M. Burkley, K. Nag, R. C. Taylor, and V. K. Moudgil. 1994. Taxol and cisplatin inhibit proliferation of T47D human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202:1413-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koonin, E. V., S. F. Altschul, and P. Bork. 1996. BRCA1 protein products. Functional motifs. Nat. Genet. 13:266-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krek, W., D. M. Livingston, and S. Shirodkar. 1993. Binding to DNA and the retinoblastoma gene product promoted by complex formation of different E2F family members. Science 262:1557-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le, X. F., A. McWatters, J. Wiener, J. Y. Wu, G. B. Mills, and R. C. Bast, Jr. 2000. Anti-HER2 antibody and heregulin suppress growth of HER2-overexpressing human breast cancer cells through different mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 6:260-270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, J. S., K. M. Collins, A. L. Brown, C. H. Lee, and J. H. Chung. 2000. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature 404:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenferink, A. E., D. Busse, W. M. Flanagan, F. M. Yakes, and C. L. Arteaga. 2001. ErbB2/neu kinase modulates cellular p27(Kip1) and cyclin D1 through multiple signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 61:6583-6591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, S., N. S. Ting, L. Zheng, P. L. Chen, Y. Ziv, Y. Shiloh, E. Y. Lee, and W. H. Lee. 2000. Functional link of BRCA1 and ataxia telangiectasia gene product in DNA damage response. Nature 406:210-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohi, J. 2001. Laminin-5 in the progression of carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 94:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorick, K. L., J. P. Jensen, S. Fang, A. M. Ong, S. Hatakeyama, and A. M. Weissman. 1999. RING fingers mediate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2)-dependent ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11364-11369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marquis, S. T., J. V. Rajan, A. Wynshaw-Boris, J. Xu, G. Y. Yin, K. J. Abel, B. L. Weber, and L. A. Chodosh. 1995. The developmental pattern of Brca1 expression implies a role in differentiation of the breast and other tissues. Nat. Genet. 11:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsushime, H., D. E. Quelle, S. A. Shurtleff, M. Shibuya, C. J. Sherr, and J. Y. Kato. 1994. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:2066-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miki, Y., J. Swensen, D. Shattuck-Eidens, P. A. Futreal, K. Harshman, S. Tavtigian, Q. Liu, C. Cochran, L. M. Bennett, W. Ding, et al. 1994. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 266:66-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miralem, T., A. Wang, C. I. Whiteside, and D. M. Templeton. 1996. Heparin inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent c-fos induction in mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17100-17106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miralem, T., C. I. Whiteside, and D. M. Templeton. 1996. Collagen type I enhances endothelin-mediated contraction and induces nonproliferating phenotype in mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 270:F960-F970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyamoto, S., H. Teramoto, J. S. Gutkind, and K. M. Yamada. 1996. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J. Cell. Biol. 135:1633-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteiro, A. N., A. August, and H. Hanafusa. 1996. Evidence for a transcriptional activation function of BRCA1 C-terminal region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13595-13599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Brien, K. A., S. J. Lemke, K. S. Cocke, R. N. Rao, and R. P. Beckmann. 1999. Casein kinase 2 binds to and phosphorylates BRCA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260:658-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connell, F. C., and F. Martin. 2000. Laminin-rich extracellular matrix association with mammary epithelial cells suppresses Brca1 expression. Cell Death Differ. 7:360-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pao, G. M., R. Janknecht, H. Ruffner, T. Hunter, and I. M. Verma. 2000. CBP/p300 interact with and function as transcriptional coactivators of BRCA1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1020-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajan, J. V., M. Wang, S. T. Marquis, and L. A. Chodosh. 1996. Brca2 is coordinately regulated with Brca1 during proliferation and differentiation in mammary epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13078-13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rock, M. T., W. H. Brooks, and T. L. Roszman. 1997. Calcium-dependent signaling pathways in T cells. Potential role of calpain, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b, and p130Cas in integrin-mediated signaling events. J. Biol. Chem. 272:33377-33383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruffner, H., W. Jiang, A. G. Craig, T. Hunter, and I. M. Verma. 1999. BRCA1 is phosphorylated at serine 1497 in vivo at a cyclin-dependent kinase 2 phosphorylation site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4843-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruffner, H., C. A. Joazeiro, D. Hemmati, T. Hunter, and I. M. Verma. 2001. Cancer-predisposing mutations within the RING domain of BRCA1: loss of ubiquitin protein ligase activity and protection from radiation hypersensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5134-5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruffner, H., and I. M. Verma. 1997. BRCA1 is a cell cycle-regulated nuclear phosphoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7138-7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salomon, D. S., R. Brandt, F. Ciardiello, and N. Normanno. 1995. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 19:183-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satterwhite, D. J., N. Matsunami, and R. L. White. 2000. TGF-β1 inhibits BRCA1 expression through a pathway that requires pRb. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276:686-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scully, R., J. Chen, R. L. Ochs, K. Keegan, M. Hoekstra, J. Feunteun, and D. M. Livingston. 1997. Dynamic changes of BRCA1 subnuclear location and phosphorylation state are initiated by DNA damage. Cell 90:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scully, R., J. Chen, A. Plug, Y. Xiao, D. Weaver, J. Feunteun, T. Ashley, and D. M. Livingston. 1997. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell 88:265-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shao, N., Y. L. Chai, E. Shyam, P. Reddy, and V. N. Rao. 1996. Induction of apoptosis by the tumor suppressor protein BRCA1. Oncogene 13:1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw, L. M., I. Rabinovitz, H. H.-F. Wang, A. Toker, and A. M. Mercurio. 1997. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the α6β4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell 91:949-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimizu, K., P.-Y. Bourillot, S. J. Nielsen, A. M. Zorn, and J. B. Gurdon. 2001. Swift is a novel BRCT domain coactivator of Smad2 in transforming growth factor β signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3901-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sjaastad, M. D., B. Angres, R. S. Lewis, and W. J. Nelson. 1994. Feedback regulation of cell-substratum adhesion by integrin-mediated intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8214-8218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Somasundaram, K., H. Zhang, Y. X. Zeng, Y. Houvras, Y. Peng, G. S. Wu, J. D. Licht, B. L. Weber, and W. S. El-Deiry. 1997. Arrest of the cell cycle by the tumour-suppressor BRCA1 requires the CDK-inhibitor p21WAF1/CiP1. Nature 389:187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spinardi, L., S. Einheber, T. Cullen, T. A. Milner, and F. G. Giancotti. 1995. A recombinant tail-less integrin beta 4 subunit disrupts hemidesmosomes, but does not suppress alpha 6 beta 4-mediated cell adhesion to laminins. J. Cell Biol. 129:473-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stanley, J. R., D. T. Woodley, S. I. Katz, and G. R. Martin. 1982. Structure and function of basement membrane. J. Investig. Dermatol. 79(Suppl. 1):69S-72S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sundberg, C., and K. Rubin. 1996. Stimulation of beta1 integrins on fibroblasts induces PDGF independent tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGF beta-receptors. J. Cell Biol. 132:741-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas, J. E., M. Smith, J. L. Tonkinson, B. Rubinfeld, and P. Polakis. 1997. Induction of phosphorylation on BRCA1 during the cell cycle and after DNA damage. Cell Growth Differ. 8:801-809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]