Abstract

To understand the relationship between conformational maturation and quality control–mediated proteolysis in the secretory pathway, we engineered the well-characterized degron from the α-subunit of the T-cell antigen receptor (TCRα) into the α-helical transmembrane domain of homotrimeric type I integral membrane protein, influenza hemagglutinin (HA). Although the membrane degron does not appear to interfere with acquisition of native secondary structure, as assessed by the formation of native intrachain disulfide bonds, only ∼50% of nascent mutant HA chains (HA++) become membrane-integrated and acquire complex N-linked glycans indicative of transit to a post-ER compartment. The remaining ∼50% of nascent HA++ chains fail to integrate into the lipid bilayer and are subject to proteasome-dependent degradation. Site-specific cleavage by extracellular trypsin and reactivity with conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies indicate that membrane-integrated HA++ molecules are able to mature to the plasma membrane with a conformation indistinguishable from that of HAwt. These apparently native HA++ molecules are, nevertheless, rapidly degraded by a process that is insensitive to proteasome inhibitors but blocked by lysosomotropic amines. These data suggest the existence in the secretory pathway of at least two sequential quality control checkpoints that recognize the same transmembrane degron, thereby ensuring the fidelity of protein deployment to the plasma membrane.

INTRODUCTION

Biogenesis of integral membrane proteins in metazoan cells is a highly ordered process beginning with translocation of nascent polypeptide chains across the ER membrane and culminating in delivery of natively folded protein complexes to their correct cellular destinations. Folding of these proteins is complex, occurring in three distinct environments: lumen, cytoplasm, and within the plane of the bilayer. Extensive covalent modification—including proteolytic processing, N- and O-linked glycosylation and disulfide bond formation—as well as assembly into homo- and hetero-oligomeric complexes are all required for conformational maturation. “Quality control” (QC) systems contribute to the fidelity of protein biogenesis by recognizing incorrectly folded polypeptides and unassembled subunits and preventing their deployment, either by prolonging their interaction with the folding machinery or by targeting them for destruction (Bonifacino and Weissman, 1998; Ellgaard and Helenius, 2001).

A principal “checkpoint” for QC in the secretory pathway occurs at the level of the ER. The lumen of this compartment contains highly specialized molecular chaperones and enzymes to promote folding and assemble oligomeric membrane and secretory proteins. Misfolded or mis-assembled proteins are unable to mature to the Golgi apparatus and are ultimately delivered to cytoplasmic proteasomes for degradation (Kopito, 1997). Substrates of this ER-associated degradation (ERAD) process must be first dislocated across the ER membrane to the cytosol by a process that appears to require the Sec61 translocon (Pilon et al., 1997; Plemper and Wolf, 1999) and the cytoplasmic AAA ATPase p97/cdc48 (Ye et al., 2001; Lord et al., 2002; Rabinovich et al., 2002). Although proteasome inhibitors and dominant negative ubiquitin mutants can stabilize ERAD substrates, they do not lead to increased yield of folded product, (Ward et al., 1995; Mancini et al., 2000), suggesting that misfolded proteins become committed to a degradative fate even in the absence of degradation. However, despite extensive genetic dissection and biochemical characterization of ERAD, neither the critical elements of the ER QC system, which recognizes misfolded or misassembled proteins, nor the nature of the specific features of these proteins that are recognized has been defined.

In the cytosol, proteins are tagged for proteasomal degradation by covalent attachment of a polyubiquitin tag—substrate recognition is therefore presumed to be mediated by specific combination of enzymes that attach ubiquitin to substrates (Bonifacino and Weissman, 1998). Because there is no ubiquitin or ubiquitin conjugation machinery in the ER lumen, other mechanisms must be responsible for the initial recognition of lumenal ERAD substrates in this compartment. In contrast, membrane-spanning proteins could, in principle, be recognized in any of the three environments (lumen, membrane, cytoplasm) in which they fold. For example, mutations that interfere with the folding of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a polytopic integral membrane glycoprotein with extensive cytoplasmically exposed domains, cause prolonged interaction with cytoplasmic Hsp70 (Yang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2001); proteasome-mediated degradation is accompanied by the formation of readily detectable multiubiquitin ladders (Ward et al., 1995). In contrast proteasomal degradation of unassembled alpha subunits of the T-cell antigen receptor (TCRα), a type I membrane protein with only 4–5 amino acids exposed to the cytoplasm, is directed by a “degron” composed of two positively charged amino acid residues within the single membrane-spanning segment (Bonifacino et al., 1990).

Although charged and polar amino acid side chains are normal constituents of transmembrane domains in polytopic proteins like ion channels and transporters, such residues are relatively rare in the membrane-spanning domains of monotopic proteins (von Heijne and Gavel, 1988). In T-cells, TCRα, must assemble with at least seven other monotopic integral membrane polypeptides (TCRβ, CD3γ, δ, ε2, ζ2) to mature to the cell surface (Chen et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1998). Charge interactions among the various transmembrane domains of the TCR complex subunits are thought to play a dual role in stabilizing the complex through charge-pair interactions and signaling the degradation of individual unassembled subunits (Chen et al., 1988). Indeed TCRα chains that fail to assemble are efficiently degraded shortly after synthesis by cytoplasmic proteasomes (Huppa and Ploegh, 1997; Yu et al., 1997). Substitution of the two charged residues, Arg and Lys at positions 5 and 10, respectively, of the putative TM domain of TCRα with hydrophobic amino acids leads to profound stabilization of the protein in the absence of its oligomeric partners, demonstrating that these charged residues are necessary to target unassembled TCRα chains for ERAD (Yang et al., 1998). Importing either the TCRα TM or just the two charged residues into corresponding positions of otherwise stable proteins like CD4 (Shin et al., 1993) or Tac (Bonifacino et al., 1990) targets them to the ERAD pathway. Thus, the two positively charged residues in the TM of TCRα constitute a degron that is both necessary and sufficient for ERAD, at least for some type I membrane proteins.

The objective of the work reported here is to identify the features of the QC machinery that recognize a specific ERAD degron. To this end, we introduced the TCRα degron (or two positively charged residues) into the hydrophobic TM domain of influenza hemagglutinin (HA), a normally stable and efficiently folded type I transmembrane glycoprotein (84 kDa, 549 amino acids) with multiple folding domains (Wilson et al., 1981). In HA-infected or -transfected cells, the large ectodomain (513 residues) is cotranslationaly translocated into the ER, the signal peptide is cleaved, and N-glycosylation occurs cotranslationally on seven sites (Braakman et al., 1991). The ectodomain of the mature protein contains 12 cysteine residues, all of which form intrachain disulfide bonds (Chen et al., 1995). HA is synthesized as a monomer but forms noncovalently associated homotrimers in the ER. Trimerization is a prerequisite for transport of HA molecules out of the ER (Copeland et al., 1986; Braakman et al., 1991). In this study we exploit the wealth of detailed information on HA structure and the availability of conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies to investigate the relationship between conformational maturation and ERAD. Although HA molecules containing the TCRα degron acquire posttranslational modifications and form intrachain disulfide bonds that are indistinguishable from those that accompany the folding of wild-type HA, mutant HA is rapidly degraded. Surprisingly, we find that mutant HA molecules partition between proteasome-dependent ERAD and a post-ER, lysosome-dependent degradation pathway. These data establish that a same degron is recognized by two distinct QC systems that together serve to eliminate nonnative proteins from multiple compartments of the secretory pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

MG132, brefeldin A, trypsin-TPCK, and soybean trypsin inhibitor were obtained from Sigma. Lactacystin was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation (San Diego, CA). Anti-mouse Ig-peroxidase was purchased from Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, MD) and anti-rabbit Ig-peroxidase was obtained from Amersham Life Science (Piscataway, NJ). HA cDNA from the HA/Aichi/68 strain X31 influenza virus and polyclonal anti- HA/Aichi/68 strain X31 virus rabbit (PINDA) and conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies N2, F1, and F2 were generously provided by Ari Helenius (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology). Recombinant adenovirus expressing wild-type and mutant HA were engineered using the AdEasy vector system (Quantum Biotechnologies, Montreal, Quebec). Monolayers of HEK293 cells were infected with these adenovirus constructs (He et al., 1998).

Metabolic Labeling and Pulse-Chase

Twenty-four hours after infection, HEK 293 cells were preincubated in Met, Cys DMEM-free medium containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were labeled for 30 min (or 5 min for the experiment in Figure 3) at 37°C with 500 μCi/ml [35S]Met+Cys (NEN Life Sciences) in the same medium. After the pulse, the radiolabeling medium was removed, and the cells washed twice with 1 ml DMEM and chased in culture medium supplemented with 5 mM Met and 5 mM Cys. After the chase, cells were washed twice with 2 ml ice-cold PBS and scraped in 600 μl extraction buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 20 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer-Mannheim), as described by Braakman et al. (1991). Cell extracts were then tumbled for 20 min at 4°C and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The radiolabeled supernatant was immunoprecipitated as described below. For the experiment in Figure 3, the chase was stopped by aspirating the medium and washing the cells twice with ice-cold PBS containing 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide, which was also present during the lysis step.

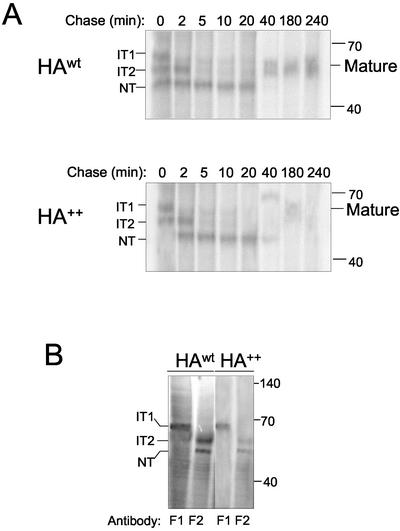

Figure 3.

HA++ can form native disulfide bonds. (A) Pulse-chase analysis of HAwt (top panel) or HA++ (bottom panel) under nonreducing conditions. The mobility of intermediates (IT1, IT2) in disulfide bond formation, and native (NT) core-glycosylated forms are indicated on the left. Mobility of post-ER form (mature) is indicated on the right. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the PINDA antibody. (B) Detection of folding intermediates of HAwt or HA++. Cells were metabolically labeled (with 35S Cys/Met) to steady state and immunoprecipitation with conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies F1 and F2 as indicated. Samples were analyzed on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates were precleared 2 h at 4°C with nonimmune serum. After 3 min centrifugation at 10,000 × g, the supernatant was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with the PINDA polyclonal antibody previously complexed with protein A-Sepharose (Zymed). Immune complexes were then retrieved by a brief centrifugation. The complexes with the PINDA polyclonal antibody and the N2 mAb were washed twice with wash buffer (0.05% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.6) and once with PBS. The F1 and F2 complexes were washed with 0.5% Triton X-100 in MNT (20 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Precipitated proteins were separated from antibody-protein A-Sepharose complexes by boiling for 5 min in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, and Laemmli buffer supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol (unless otherwise indicated), and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging.

Endoglycosidase H and PNGase F Digestion

Where noted, cell extracts were digested with endoglycosidase H or peptide-N-glycanase F (New England Biolabs) before electrophoresis. Samples were first denatured (5% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol) at 100°C for 10 min. Oligosaccharides were cleaved with endoH (500 U in 50 mM sodium citrate) or PNGase (500 U in 50 mM sodium phosphate) for 16 h at 37°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Alkali and Triton X-114 Extraction

Microsomes from HEK293 cells expressing wild-type and mutant forms of HA were prepared and treated as described by (Nicchitta and Blobel, 1993). Microsomes were extracted for 30 min on ice by diluting 10-fold in 50 mM CAPS- HEPES buffer, pH 9.5 and overlaid onto a 200-μl cushion of 0.5 M sucrose, 50 mM triethanoloamine, pH 7.4. Membranes were collected by centrifugation in a TLA100.2 Beckman rotor for 20 min at 60,000 rpm. Pelleted membranes were resuspended in 0.25 M sucrose, 50 mM triethanoloamine, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT and stored on ice before SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Triton X-114 extraction was performed as described by Bordier (1981) and Shin et al. (1993). Twenty-four hours after infection, monolayers of HEK293 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and solubilized in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-114 at 0°C for 20 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was overlaid on a 6% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.06% Triton X-114, incubated 3 min at 30°C, and centrifuged for 3 min at 300 × g and 25°C. After centrifugation, the detergent phase was found as an oily droplet at the bottom of the tube. The aqueous (upper) phase was removed and incubated with 0.5% fresh Triton X-114 at 0°C for 5 min followed by centrifugation. The mixture was overlaid on a sucrose cushion as before. The aqueous phase from the second extraction was mixed with 2% Triton X-114 at 0°C and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. After separation, Triton X-114 and buffer were added, respectively, to the two aqueous phases and to the detergent phase in order to obtain equal volumes and approximately the same salt and detergent content for both samples. Aliquots of the separated phases were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. The efficacy of separation of integral membrane and lumenal proteins by alkaline extraction and Triton X-114 phase partitioning methods was confirmed by monitoring the distribution of BiP (a lumenal protein) and Na-K ATPase (an integral membrane protein; unpublished data).

Trypsin Digestion of Cell Surface HA

The protocol used by Copeland et al. (1986) was used to detect HA at the cell surface. Briefly cells were trypsinized with tosylamidephenylethylchloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin (TPCK-trypsin) at 100 μg/ml in PBS for 30 min at 0°C. Trypsination was stopped by two 5-min washes in soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 μg/ml in PBS) before lysis with HA extraction buffer, SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Flow Cytometry

Forty-eight hours after infection, COS7 cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS and centrifuged at 1200 rpm. Cells were resuspended in PBS + 2% BSA. Primary antibody (PINDA or N2) was added and incubated for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were washed for in PBS + 2% BSA and incubated with fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody for 20 min at 4°C. The cells were washed for 5 min in PBS + 2% BSA + 1 mg/ml propidium iodide for viability gating. The samples were analyzed on Coulter Epics XL-MCL model flow cytometer.

Intracellular Cross-linking of HA Molecules Using Dimethyl Adipimidate

Dimethyl adipimidate (150 μl, DMA; Pierce) at 15 μg/ml in 0.2 M triethanolamine, pH 8.5, was added to 75 μl of cell extract and incubated overnight at RT. The reaction was terminated by addition of 75 μl of 0.2 M glycine. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

RESULTS

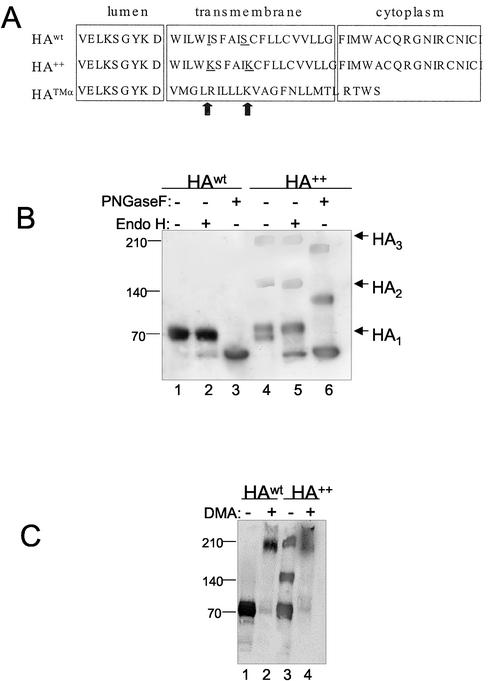

HA Molecules with Mutant Transmembrane Domains Form SDS-resistant Oligomers

To mimic the effect of destabilizing amino acids within the TM domain of an otherwise stable integral membrane protein, we engineered an HA variant (HA++) containing two Lys residues, replacing Ile and Ser at predicted positions 5 and 10, respectively, of the predicted transmembrane helix of HA (Figure 1A). Immunoblot analysis revealed that wild-type HA(HAwt) expressed by infection with recombinant adenovirus in HEK293 cells migrated as a single band of Mr ∼75,000, corresponding to the mobility of authentic mature HA (Braakman et al., 1991; Figure 1B, lane 1). This species was digested by protein:N-glycanaseF (PNGaseF), but not by endoglycosidase H (endoH), suggesting that it contains complex oligosaccharides, indicative of its maturation beyond the cis-Golgi. In contrast, HA++ was resolved into a four distinct species: a doublet at Mr ∼70,000 and Mr ∼80,000 and higher molecular weight forms corresponding to the mobility expected for HA dimers and trimers (Figure 1B, lane 4). The three slower mobility species were resistant to endoH digestion, whereas the faster-migrating Mr ∼70,000 form increased in mobility after digestion with the enzyme. Thus, although HAwt appears to fold efficiently in HEK293 cells, only a fraction of mutant HA escapes the ER and matures to a post-ER compartment where it acquires complex N-glycans. Some of this endoH resistant HA++ appears to form SDS-resistant oligomers.

Figure 1.

HA molecules with mutant transmembrane domains form SDS-resistant oligomers. (A) Schematic representation of the HA constructs used. The HA++ variant contains two Lys residues replacing Ile and Ser at position 5 and 10, respectively (indicated by vertical arrow). The HATMα chimeric protein consists of the ectodomain of HA linked to the TMD and cytoplasmic tail of TCRα. Mutated residues are shown in underlined letters. (B) Oligosaccharide analysis. Cell extracts from cells expressing HAwt and HA++ (containing the same total protein concentration) were treated with endoH (lanes 2 and 5) or PNGase F (lanes 3 and 6), or left untreated (lanes 1 and 4). After SDS-PAGE (4–15% gradient) under reducing conditions, samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis using the HA polyclonal antibody, PINDA. (C) Cross-linking. Dimethyladipimidate (DMA) was added to cell extracts as indicated and incubated overnight. Cell extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot using the HA polyclonal antibody, PINDA.

Oligomerization of wild-type HA into noncovalent trimers accompanies the normal conformational maturation of wild-type HA and is a prerequisite for transport to the cis Golgi (Copeland et al., 1986, 1988). Wild-type HA trimers are labile under reducing SDS page conditions and can be detected only after covalent cross-linking (Gething et al., 1986). In the presence of the homobifunctional cross-linker DMA, HAwt expressed in HEK293 cells was shifted to a higher molecular species corresponding roughly to the size predicted for a homotrimer (Figure 1C, lane 2). The mobility of this cross-linked band was similar to that of the high molecular weight, apparently trimeric form of HA++ in the absence of cross-linker (Figure 1C lane 3). After cross-linking, all of the HA++ shifted to this high molecular weight form (Figure 1C, lane 4). These nonnative, SDS-resistant oligomeric HA++ species persisted even when cells were lysed in the presence of alkylating agents such as N-ethyl maleimide, indicating that they are not oxidative artifacts formed upon extraction or electrophoresis (unpublished data).

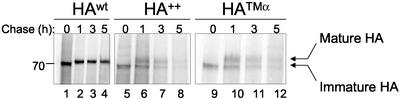

HA++ Is Metabolically Unstable

To determine if charged residues in the transmembrane domain of HA served as a degradation signal, we analyzed the stability of HAwt, HA++, and a chimeric protein, HATMα, consisting of the ectodomain of HA linked to the transmembrane and short cytoplasmic domain of TCRα (Figure 1A), by pulse-chase analysis followed by immunoprecipitation with a polyclonal antibody (PINDA) that recognizes all HA molecules irrespective of their conformational state (Doms et al., 1985; Figure 2). After a 30-min pulse with [35S]-(Met+Cys), HAwt migrated as a single band of Mr ∼75,000 (Figure 2, lane 1), which was chased to a slower-migrating band corresponding to the Golgi-processed form (mature HA; Figure 2, lane 2). The assignment of these bands to mature and immature was also confirmed by endoH digestion (unpublished data). HAwt was stable during the 5-h chase period. In contrast, although both HA++ and HATMα were initially synthesized as single electrophoretic species corresponding in mobility to that of immature HAwt (Figure 2, lanes 5 and 9) by 1-h chase only a fraction, representing ∼50% of the mutant proteins, was converted to slower migrating species. Moreover, both the mature and the immature species were unstable, exhibiting half-lives of ∼2 h, compared with >9 h for HAwt (Figure 2, lanes 6–8 and 10–12). No HA-reactive material was detected in the detergent-insoluble fractions, indicating that the disappearance from the gel during the chase is the result of degradation (unpublished data). This conclusion is also confirmed by the action of lysosomotropic agents and proteasome inhibitors (see below). These results suggest that the presence of two positively charged residues in the transmembrane domain diminishes the efficiency of HA maturation to the Golgi apparatus and is sufficient to serve as a degron for rapid degradation. In contrast, introduction of a single lysine residue into the transmembrane domain of HA at position 5 or 10 had no measurable effect on either stability or the maturation of HA (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

HA++ is metabolically unstable. Cells expressing HAwt (lanes 1–4), and HA++ (lanes 5–8), or an HA-TCRα chimera (lanes 9- 12) were pulse-labeled and chased for the times indicated. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the PINDA antibody. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE analysis under reducing conditions and the radioactivity was detected by phosphorimage analysis.

HA++ Can Form Native Disulfide Bonds

The immunoblot and the metabolic pulse-chase experiments suggest that the stability of HA is strongly affected by the presence of two positive charges in its transmembrane domain. To determine whether the two introduced lysine residues alter the folding of HA, we monitored the folding process of both HA forms using a pulse-chase approach under nonreducing conditions developed by (Braakman et al., 1991) (Figure 3). Cells expressing HAwt or HA++ were pulsed for a short interval (5′), which allowed us to study the events during the first minutes after synthesis was completed. At the indicated chase times, the cells were treated with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM) to alkylate remaining free sulfhydryl groups and trap folding intermediates. Formation of intrachain disulfide bonds was monitored by the changes in mobility of HA bands in nonreducing SDS-PAGE (Figure 3A).

For HAwt, after a 5-min pulse, two major folding intermediates, IT1 and IT2, were detected as well as the fully oxidized, untrimmed native HA (NT), in agreement with the data of Braakman et al. (1991). The label in these folding intermediates decreased progressively with time of chase. By 40 min of chase the label was almost exclusively present in the corresponding NT band. This form could be chased into a slower-migrating form corresponding to the endoH-resistant, core-glycosylated species, labeled “mature.” When HA++ was analyzed under the same conditions, after a 5-min pulse, the folding intermediates IT1 and IT2 were detected. The NT intermediate was not detectable at this time point, suggesting that the IT2-NT transition of HA++ was slightly slower than that of HAwt. In contrast to HAwt, HA++ was not chased into a band corresponding to the mature form. Instead, some HA++ remained in the NT form, while some formed a slower migrating species. Both the NT and the slower migrating form of HA++ were unstable and were undetectable by the 180-min time point. Together, these data suggest that, although the HA++ mutation slightly retards the rate at which native disulfide bonds form, it does not grossly affect the formation of native disulfide bonds.

To confirm whether the ectodomain of HA++ is able to fold into a native-like conformation, as suggested by the formation of native disulfide bonds, we performed immunoprecipitation of metabolically labeled HAwt and HA++ using conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize distinct HA folding intermediates (Doms et al., 1985; Copeland et al., 1986; Figure 3B). Immunoprecipitation of either HAwt or HA++ with the F1 antibody, which recognizes an epitope unique to the IT1 folding intermediate (Braakman et al., 1991), identified one band of the expected mobility in both HA forms. Likewise, the F2 antibody, which recognizes the IT2 and NT forms, recognized identical species in both HAwt and HA++. These data indicate that, although the introduction of charged residues into the TM domain of HA destabilizes the protein and reduces the efficiency of its ability to mature beyond the ER, it does not alter the folding of the ectodomain.

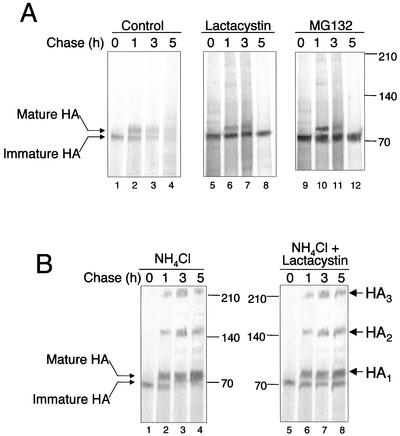

Lysosomes and Proteasomes Both Contribute to the Degradation of HA++

To determine the mechanisms by which mutant HA is degraded, we examined the effect of proteasome inhibitors on the stability of HA++ (Figure 4A). Inclusion of either MG132 or the more specific proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin in the chase medium dramatically stabilized the band corresponding to endoH-sensitive, immature HA++. In contrast, the slower migrating endoH resistant “mature” form was not significantly stabilized by inhibitors of the proteasome. The converse was observed when HA++-expressing cells were exposed to the lysosomotropic agent, NH4Cl, which inhibits lysosomal hydrolyase activity by alkalinizing the lumen of lysosomes and other acidic organelles (Figure 4B). NH4Cl strongly stabilized the mature, Golgi-processed form of HA++ without influencing the stability of the immature form (Figure 4B). Strikingly, treatment of HA++-expressing cells with NH4Cl led to the appearance of high molecular weight bands corresponding in mobility to HA dimers and trimers.

Figure 4.

Lysosomes and proteasomes both contribute to the degradation of HA++. (A) Effect of proteasome inhibitors on the degradation of HA++. Cells were pulse labeled and chased in the presence or absence as indicated of 10 μM lactacystin (lanes 5–8) or 50 μM MG132 (lanes 9–12). Immunoprecipitation and fluorography was performed as in Figure 2. (B) Effect of 5 mM NH4Cl (Figure 5B, lanes 1–4) or the combination of lactacystin and NH4Cl on the degradation of HA++. Pulse-chase analysis was as above.

These data suggest that HA++ partitions shortly after (or during) synthesis into two fractions each with a distinct cellular fate. About half of the newly synthesized HA++ molecules fail to mature to a post-ER compartment and are rapidly degraded by proteasomes. A similar fraction of newly synthesized HA++ molecules mature to a post-ER compartment where they acquire complex oligosaccharides and can form dimers and trimers. However, unlike HAwt, these “mature” HA++ oligomers are insoluble in SDS. Moreover, their stabilization in the presence of NH4Cl suggests that they are degraded in lysosomes. This stabilization is not an artifact of NH4Cl treatment, because SDS-resistant HA++ oligomers are also stabilized in the presence of brefeldin A, a fungal metabolite that inhibits transport from ER to Golgi (unpublished data).

Interestingly, the amount of label in mature or oligomeric HA++ after a 5-h chase was not increased by simultaneous treatment with both lactacystin and NH4Cl (compared with NH4Cl alone), suggesting that the HA++ molecules that were targeted for proteasomal degradation were not competent for maturation to a post-ER compartment when their degradation was inhibited (Figure 4B). These data suggest that some HA++ molecules become committed to a degradation fate, revealing the existence of a quality control “checkpoint” in the ER that identifies and sequesters substrates of ERAD early in protein biogenesis. Polypeptides that have not transited this checkpoint are evidently not competent for export beyond the ER, even if their degradation is blocked (i.e., by proteasome inhibititors). Some HA++ molecules appear to escape this ERAD checkpoint and acquire complex oligosaccharides indicative of transit through the Golgi apparatus; these molecules, which, differ from mature HAwt in their SDS solubility behavior, are evidently culled by a second level of quality control that targets them for lysosomal destruction.

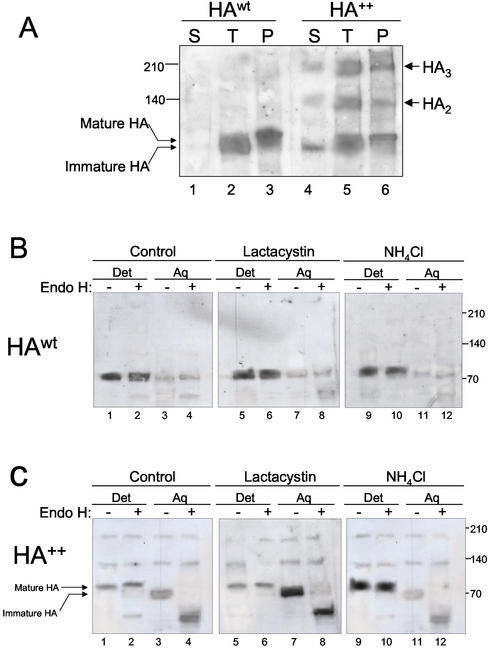

HA++ Molecules Partition Between Membrane-integrated and -soluble Forms

One way in which charged amino acid side chains within a transmembrane domain might influence the fate of a polypeptide in the ER could be by interfering with the partitioning of the nascent transmembrane segment into the hydrophobic core of the bilayer. Indeed, substitution of the TM domain of CD4 with that from TCRα suppresses membrane integration and promotes secretion of the unanchored chimeric protein into the culture medium (Shin et al., 1993). To assess whether a fraction of HA++ molecules had failed to become integrated into the bilayer, microsomes from cells expressing either HA++ or HAwt were extracted with alkali and subjected to sedimentation (Figure 5A). Although HAwt was almost completely recovered in the pellet fraction, a significant fraction of HA++ failed to sediment. This material consisted of nearly all of the immature HA++ and only a small fraction of oligomer. To confirm this result, we used phase separation in Triton X-114 to assess the extent of membrane integration of HA++ (Figure 5, B and C). As expected, HA++ mainly partitioned into the detergent phase and was predominantly endoH resistant (Figure 5B). In contrast, HA++ partitioned into both the detergent and the aqueous phases, indicating that a fraction of HA++ molecules were not membrane integrated. Moreover, the aqueous (nonintegrated) fraction was comprised mostly of immature HA++ molecules, as assessed by endoH digestion, whereas the detergent fraction contained almost exclusively mature HA++ (Figure 5C). This conclusion was strengthened by the finding that lactacystin treatment caused a massive increase in the abundance of the aqueous-extracted, immature-sized species with no significant change in the amount of membrane integrated material. Likewise, treatment with NH4Cl resulted in an increase in the amount of mature, detergent-soluble, membrane-integrated forms of HA++ without a significant change in immature HA++. These data suggest that a large fraction of the ER-retained mutant forms fail to become integrated into the lipid bilayer. Moreover, the absence or detectable HA++ from culture medium (unpublished data) supports the conclusion that unintegrated HA++ molecules do not exit the ER.

Figure 5.

Mutant HA partitions into soluble and membrane-associated forms. (A) Alkaline extraction of HAwt and HA++. Microsomes from HEK293 cells expressing HAwt (lanes 1–3) and HA++ (lanes 4–6) were extracted on ice at pH 9.5 as detailed in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Extracted membranes were sedimented through a sucrose cushion. Aliquots of supernatant (S), pellet (P), and total microsomal fractions (T) were analyzed by immunoblotting using PINDA antibody. (B) Phase partitioning of HA++ in Triton X-114. Cell extracts from cells not treated (lanes 1–4) or pretreated with either 10 μM lactacystin (lanes 5–8) or 5 mM NH4Cl (lanes 9–12) were extracted with Triton X-114 as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, separated into aqueous (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12) and detergent (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10) phases and, where indicated (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12), digested with endoH. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with PINDA antibody. Only the data from the second aqueous phase is shown. Similar results were obtained from the first extraction.

HA++ and HAwt Both Acquire Native Trimer Structure

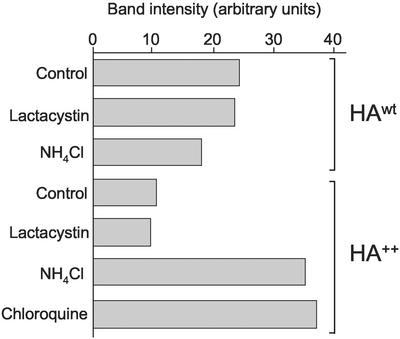

The preceding data suggest that ∼50% of newly synthesized HA++ fails to integrate into the ER membrane and is degraded by a proteasome-dependent pathway without transiting the Golgi complex. The remaining ∼50% of newly synthesized HA++ molecules become integrated into the bilayer and are able to mature to a post-ER compartment, where they acquire complex-type oligosaccharides. Some of these molecules apparently form dimers and trimers, which unlike HAwt oligomers, are stable in SDS. We therefore used a conformation-specific mAb, N2, which specifically recognizes HA trimers at neutral pH to probe the conformation of HA++. The epitope recognized by this antibody is located close to the interface between the HA1 top domain of the native HA trimer (Wiley et al., 1981; Copeland et al., 1988). Cells expressing either HAwt or HA++ were metabolically labeled, immunoprecipitated with N2 under native conditions, and subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions. The amount of labeled HAwt precipitated was considerably greater than that of HA++; this was not significantly affected by treatment of the cells with either lactacystin or NH4Cl, consistent with the fact that HAwt is an efficiently folded and stable molecule (Figure 6). In contrast, the amount of label recovered in HA++ was dramatically increased by treatment with the lysosomotropic agents NH4Cl and chloroquine, but not by proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin. Therefore HA++ molecules that escape surveillance by ER quality control are still degraded by lysosomes even though they acquire a native trimeric structure recognized by the N2 antibody. These data suggest the existence of a second, lysosome-dependent quality control mechanism, which operates on molecules with native ectodomains, and mutant transmembrane domains.

Figure 6.

HA++ and HAwt acquire native trimer structure. Cells expressing HAwt and HA++ were pulse-labeled with 35S (Met+Cys) for 30 min and chased for 2 h in the absence of drugs or in the presence of 10 μM lactacystin, 5 mM NH4Cl, or 0.2 mM chloroquine as indicated. Samples were immunoprecipitated with the trimer specific (N2) mAb after alkylation with NEM. Radioactivity in the band corresponding to mature HA was quantified by phosphorimage analysis.

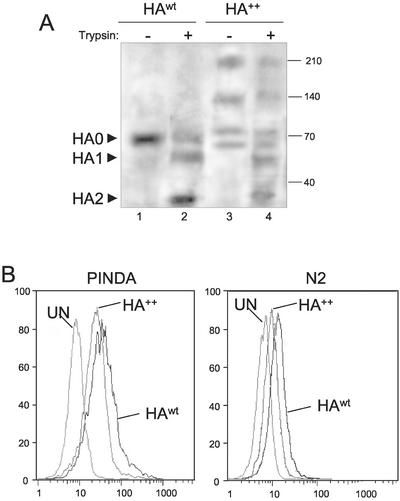

Some HA++ Molecules Reach the Cell Surface

To assess whether the Golgi-processed forms of HA++ are able to reach the cell surface, we used trypsin digestion as a way to distinguish cell surface from intracellular HA populations (Figure 7A). Cleavage of native HA molecules at the cell surface by trypsin yields two disulfide-linked glycopeptide fragments that correspond to the two fragments of HA that are normally generated endogenously in the trans-Golgi of influenza-infected cells. Because HEK293 cells lack the resident protease required, these cells display uncleaved HA (HA0) at the cell surface. Generation of fragments HA1 (corresponding to the apical domain of the protein spike) and HA2 (Copeland et al., 1986) by endogenous enzymes in the Golgi or by exogenous trypsin in the culture medium requires that HA be in a native trimeric state; monomeric and misfolded forms are digested to acid-soluble fragments too small to be detected by immunoblotting (Matlin and Simons, 1983). Thus, cleavage of HA by exogenous trypsin is a sensitive probe of both the presence of HA at the cell surface and its conformation.

Figure 7.

HA++ molecules are expressed at the cell surface. (A) Sensitivity to extracellular trypsin. Cells expressing HAwt and HA++ were untreated (lanes 1 and 3) or digested (lanes 2 and 4) with TPCK-trypsin (100 μg/ml). Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with PINDA antibody. Mobilities of bands corresponding to uncleaved HA (HA0) or the two proteolytic fragments (HA1 and HA2) are indicated. (B) Analysis of cell-surface expression of HAwt and HA++ by flow cytometry. Unfixed, untransfected COS7 cells (UN) or COS7 cells expressing HAwt and HA++ were labeled with PINDA (left) or the trimer specific N2 antibody (right) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

As anticipated, most HAwt was accessible to trypsin cleavage (Figure 7A, lanes 1 and 2), giving rise to the expected fragments: HA1 (58 kDa) and HA2 (26 kDa), with a corresponding reduction in HA0. Trypsin treatment of cells expressing HA++ (Figure 7A, lanes 3–4) also generated immunoreactive fragments corresponding to HA1 and HA2, indicating that a significant fraction of HA++ was at the cell surface in a native-like state. Surprisingly, the production of proteolytic fragments of HA++ was not accompanied by a decrease in a species corresponding to HA0; instead trypsin digestion produced a decrease in the abundance of the SDS-resistant dimer and trimer species, suggesting that some of the SDS-resistant trimers were displayed at the cell surface.

The presence of HA at the cell surface at steady state was also examined by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 7B). This analysis confirmed that the presence of both HAwt and HA++ at the cell surface. Moreover, detection of HA++ with the trimer specific (N2) antibody allowed us to conclude that some HA++ molecules detected at the cell surface are able to fold into a native-like structure.

DISCUSSION

Although a role for proteasomes in the degradation of misfolded or misassembled proteins from the early secretory pathway is now well established, the signals that target misfolded proteins for degradation, and the mechanisms by which these signals are recognized remain to be elucidated. In this study we have used a well-characterized, stable, and efficiently folded membrane protein (influenza HA), engineered with a transmembrane degron, to investigate the relationship between protein folding and quality control mediated degradation. We find that, although this degron does not interfere with folding of the HA ectodomain—as assessed by native disulfide bond formation, trimerization, trypsin sensitivity, and the acquisition of conformational epitopes—HA++ molecules are nonetheless rapidly degraded. Surprisingly, despite the presence of this degron, about half of newly synthesized HA++ molecules escape the surveillance of ER quality control and mature to the cell surface, where they are subject to degradation in an acidic compartment. The other half of nascent HA++ molecules fail to integrate into the lipid bilayer and are subject to proteasome-dependent degradation. Thus, the secretory pathway of mammalian cells appears to possess at least two checkpoints that recognize the same transmembrane degron and ensure that only correctly folded and assembled membranes are deployed.

Previous studies have mapped the signal that targets unassembled TCRα for ERAD to the unconventional TM in which the typical hydrophobic residues are punctuated by a Lys and an Arg at positions 5 and 10 of the predicted helix (Bonifacino et al., 1991; Shin et al., 1993). Those studies led to the hypothesis that potentially charged residues within the TM of a single-spanning membrane protein contribute to the stabilization of the native oligomeric complex by charge-pair interactions between TMs of adjacent subunits (Chen et al., 1988). Thus, the proteinaceous core of some oligomeric membrane proteins composed of monotopic subunits (like the T-cell receptor) may resemble that of polytopic integral membrane proteins like ion channels and transporters. Inappropriate exposure of polar amino acid side chains in the context of an otherwise hydrophobic membrane TM helix of an unassembled monotopic subunit can thus serve as a signal to the QC apparatus for retention, retrieval, or degradation.

Recognition of this unconventional TM could result from dynamic partitioning of a TM segment between the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer and the aqueous environment of the translocon. Although hydrophobic TMs readily diffuse laterally within the plane of the bilayer, away from the aqueous interior of the translocon, more polar TMs tend to remain in a metastable equilibrium at the interface between the bilayer and the translocon channel (Heinrich et al., 2000). This equilibrium could be perturbed in favor of integration if a suitable oligomeric partner with complementary charge was nearby. The absence of such a partner, as in our studies with HA++, would disfavor integration. Prolonged interaction with the translocon could result in full translocation of the TM into the lumen, driven by the folding of the ectodomain or by interaction with lumenal chaperones like BiP. Alternatively, TMs that fail to integrate after dissociation of the ribosome could be dislocated from the translocon directly to the cytoplasm, driven by interaction of unintegrated polypeptide with cytoplasmic chaperones, AAA ATPases like CDC48, or the ubiquitin-proteasome machinery. The ability of cells to secrete a chimeric protein containing the ecto- and endo-domains of CD4 and the TM from TCRα (Shin et al., 1993) suggests that charged amino acids in a TM can result in complete translocation. However, ecto-CD4-TCRα−TM chimeras with modified cytoplasmic domains (Shin et al., 1993), and analogous chimeras between TCRα and the IL-2 receptor (Bonifacino et al., 1991), like the nonintegrated fraction of HA++ in the present study, are not secreted but are instead rapidly degraded by ERAD. These findings suggest that determinants in addition to TM hydrophobicity can influence the fate of membrane proteins with charge-interrupted TMs.

Our data show that even the HA++ molecules, which are degraded by proteasomes, appear to complete the early events of folding, including formation of native disulfide bonds and acquisition of the F1 and F2 epitopes. These molecules differ from those that escape the ER in that they fail to become fully membrane integrated, as assessed by their liability to alkaline extraction and Triton X-114 phase separation. Whether these nonintegrated molecules become fully translocated to the lumen and then retrieved to the ERAD pathway, or simply remain in the aqueous phase of the translocon is an important, unresolved issue that is beyond the scope of the present study.

Finally, we observe that about half of newly synthesized HA++ molecules are able to integrate into the bilayer. Perhaps, stabilized by trimerization of the ectodomain, the TMs of HA++ are able to adopt a structure in which the positively charged amino side chains are able to be accommodated in the membrane, possibly neutralized by charge-pair interaction with negatively charged lipid head groups (von Heijne and Gavel, 1988). Whatever the mechanism is, these HA++ trimers, despite the presence of the mutated TM, appear to evade both of the known mechanisms of ER QC that are known to act on other proteins bearing this degron: degradation by cytoplasmic proteasomes (Huppa and Ploegh, 1997; Yu et al., 1997) and retrieval from the cis Golgi by KDEL receptor mediated retrograde transport (Yamamoto et al., 2001). At least some of these HA++ molecules reach the cell surface where they are indistinguishable from native HA by all available experimental criteria. Remarkably, despite their native tertiary and quaternary structures, cell surface HA++ molecules are far more unstable than HAwt and are subject to degradation in an acidic compartment. At this point we cannot exclude the possibility that some HA++ molecules that escape the ER may be degraded by direct delivery from the Golgi apparatus to lysosomes (Reggiori et al., 2000).

These observations suggest the existence of an additional level of quality control, which operates on integral membrane proteins in a post-Golgi compartment. Little is known about the mechanisms responsible for recognition and degradation of abnormal membrane proteins in the distal compartments of the secretory pathway. A post-ER QC mechanism appears to be responsible for recognition and degradation of cytoplasmic domain mutants of CFTR (Benharouga et al., 2001) and the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α-subunit (Keller et al., 2001). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that the mutant TM might perturb the conformation of the short cytoplasmic tail of HA++, resulting in its recognition by cytoplasmic chaperones, our data strongly implicate the mutant TM as the primary signal for degradation. It has been recently suggested that recognition of uncharged polar residues within TMs of monotopic cell surface receptors can function as signals for targeting to multivesicular bodies and lysosomes, thereby controlling the balance between recycling and degradation (Zaliauskiene et al., 2000). It will be important in future studies to assess the role of ubiquitin in the destruction of proteins with unconventional TMs in lysosomes. Monoubiquitination is now recognized as an important endocytic signal (Hicke, 2001). In particular, future studies will be needed to evaluate a role in HA++ degradation for the mammalian ortholog of Tul1p, a recently described ubiquitin ligase that participates in the delivery of membrane proteins with polar TMs to multivesicular bodies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Reggiori et al., 2000). Such studies will be important in developing a clearer picture of the overall coordination of layers or checkpoints of QC regulation that ensure the fidelity of protein conformation in the secretory pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marina Gelman, Neil Bence, and the other members of the Kopito laboratory for valuable discussions. The generous gifts of HA cDNA and HA antibodies from Ari Helenius are gratefully acknowledged. During part of this work L.F. was supported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). That work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK43994 to R.R.K.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–06–0363. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–06–0363.

REFERENCES

- Benharouga M, Haardt M, Kartner N, Lukacs GL. COOH-terminal truncations promote proteasome-dependent degradation of mature cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from post-Golgi compartments. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:957–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Cosson P, Shah N, Klausner RD. Role of potentially charged transmembrane residues in targeting proteins for retention and degradation within the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1991;10:2783–2793. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Suzuki CK, Klausner RD. A peptide sequence confers retention and rapid degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1990;247:79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2294595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Weissman AM. Ubiquitin and the control of protein fate in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:19–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordier C. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakman I, Hoover-Litty H, Wagner KR, Helenius A. Folding of influenza hemagglutinin in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:401–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Bonifacino JS, Yuan LC, Klausner RD. Selective degradation of T cell antigen receptor chains retained in a pre-Golgi compartment. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2149–2161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Helenius J, Braakman I, Helenius A. Cotranslational folding and calnexin binding during glycoprotein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6229–6233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland CS, Doms RW, Bolzau EM, Webster RG, Helenius A. Assembly of influenza hemagglutinin trimers and its role in intracellular transport. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1179–1191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland CS, Zimmer KP, Wagner KR, Healey GA, Mellman I, Helenius A. Folding, trimerization, and transport are sequential events in the biogenesis of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Cell. 1988;53:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doms RW, Helenius A, White J. Membrane fusion activity of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. The low pH-induced conformational change. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2973–2981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L, Helenius A. ER quality control: towards an understanding at the molecular level. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething MJ, McCammon K, Sambrook J. Expression of wild-type and mutant forms of influenza hemagglutinin: the role of folding in intracellular transport. Cell. 1986;46:939–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich SU, Mothes W, Brunner J, Rapoport TA. The Sec61p complex mediates the integration of a membrane protein by allowing lipid partitioning of the transmembrane domain. Cell. 2000;102:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppa JB, Ploegh HL. The alpha chain of the T cell antigen receptor is degraded in the cytosol. Immunity. 1997;7:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SH, Lindstrom J, Ellisman M, Taylor P. Adjacent basic amino acid residues recognized by the COP I complex and ubiquitination govern endoplasmic reticulum to cell surface trafficking of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-Subunit. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18384–18391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100691200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopito RR. ER quality control: the cytoplasmic connection. Cell. 1997;88:427–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord JM, Ceriotti A, Roberts LM. ER dislocation. Cdc48p/p97 gets into the AAAct. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R182–R184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00738-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini R, Fagioli C, Fra AM, Maggioni C, Sitia R. Degradation of unassembled soluble Ig subunits by cytosolic proteasomes: evidence that retrotranslocation and degradation are coupled events. FASEB J. 2000;14:769–778. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin KS, Simons K. Reduced temperature prevents transfer of a membrane glycoprotein to the cell surface but does not prevent terminal glycosylation. Cell. 1983;34:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicchitta CV, Blobel G. Lumenal proteins of the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum are required to complete protein translocation. Cell. 1993;73:989–998. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90276-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon M, Schekman R, Romisch K. Sec61p mediates export of a misfolded secretory protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol for degradation. EMBO J. 1997;16:4540–4548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plemper RK, Wolf DH. Endoplasmic reticulum degradation. Reverse protein transport and its end in the proteasome. Mol Biol Rep. 1999;26:125–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1006913215484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich E, Kerem A, Frohlich KU, Diamant N, Bar-Nun S. AAA-ATPase p97/Cdc48p, a cytosolic chaperone required for endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:626–634. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.626-634.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Black MW, Pelham HR. Polar transmembrane domains target proteins to the interior of the yeast vacuole. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3737–3749. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Lee S, Strominger JL. Translocation of TCR alpha chains into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and their degradation. Science. 1993;259:1901–1904. doi: 10.1126/science.8456316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G, Gavel Y. Topogenic signals in integral membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1988;174:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell. 1995;83:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley DC, Wilson IA, Skehel JJ. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza hemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature. 1981;289:373–378. doi: 10.1038/289373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature. 1981;289:366–373. doi: 10.1038/289366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Fujii R, Toyofuku Y, Saito T, Koseki H, Hsu VW, Aoe T. The KDEL receptor mediates a retrieval mechanism that contributes to quality control at the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2001;20:3082–3091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Omura S, Bonifacino JS, Weissman AM. Novel aspects of degradation of T cell receptor subunits from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in T cells: importance of oligosaccharide processing, ubiquitination, and proteasome-dependent removal from ER membranes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:835–846. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature. 2001;414:652–656. doi: 10.1038/414652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Kaung G, Kobayashi S, Kopito RR. Cytosolic degradation of T-cell receptor alpha chains by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20800–20804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaliauskiene L, Kang S, Brouillette CG, Lebowitz J, Arani RB, Collawn JF. Down-regulation of cell surface receptors is modulated by polar residues within the transmembrane domain. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2643–2655. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Nijbroek G, Sullivan ML, McCracken AA, Watkins SC, Michaelis S, Brodsky JL. Hsp70 molecular chaperone facilitates endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1303–1314. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]