Abstract

Interleukin-12 (IL-12), a heterodimeric cytokine, plays an important role in cellular immunity to several bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections and has adjuvant activity when it is codelivered with DNA vaccines. IL-12 has also been used with success in cancer immunotherapy treatments. However, systemic IL-12 therapy has been limited by high levels of toxicity. We describe here inducible expression and secretion of IL-12 in the food-grade lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis. IL-12 was expressed as two separate polypeptides (p35-p40) or as a single recombinant polypeptide (scIL-12). The biological activity of IL-12 produced by the recombinant L. lactis strain was confirmed in vitro by its ability to induce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by mouse splenocytes. Local administration of IL-12-producing strains at the intranasal mucosal surface resulted in IFN-γ production in mice. The activity was greater with the single polypeptide scIL-12. An antigen-specific cellular response (i.e., secretion of Th1 cytokines, IL-2, and IFN-γ) elicited by a recombinant L. lactis strain displaying a cell wall-anchored human papillomavirus type 16 E7 antigen was dramatically increased by coadministration with an L. lactis strain secreting IL-12 protein. Our data show that IL-12 is produced and secreted in an active form by L. lactis and that the strategy which we describe can be used to enhance an antigen-specific immune response and to stimulate local mucosal immunity.

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) is a multifunctional cytokine that was originally described as a maturation factor for cytotoxic (T) lymphocytes and a cell stimulatory factor for natural killer cells (8, 23, 28). IL-12 is a heterodimeric glycoprotein composed of two disulfide-linked chains (p35 and p40) that has numerous effects on T and natural killer cells, resulting in enhancement of cytotoxic activity and induction of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production. In experimental models, IL-12 has been shown to be involved in protection against several bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections (4, 25, 45). This cytokine has also been shown to block angiogenesis (34, 60). Finally, the immunomodulatory effects of IL-12 are reportedly beneficial in AIDS treatment (26). The immunostimulatory properties of IL-12 have led to experimentation with its use as a vaccine adjuvant (1, 3). In addition, IL-12 stimulates serum immunoglobulin G antibody responses and helps during differentiation of Th0 cells into Th1 cells (17, 21, 41). This is particularly interesting for vaccine development for antigens that are poorly immunogenic.

Local administration of IL-12 confers antitumor activity in vivo that results in regression of established tumors and reduction of metastasis in animal models (7, 43, 49). Nevertheless, systemic IL-12 therapy can have toxic effects in animals and humans (36, 38, 39) and has been a cause of mortality in clinical trials (10, 36). For example, intratumoral treatment of mice with a vaccinia virus expressing IL-12 resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition but also induced clear signs of toxicity (9).

Il-12 has also been considered for use as an adjuvant in vaccine therapies. Current therapies involving mucosal routes are limited by a lack of suitable adjuvants that can be safely given to humans. Cholera toxin and Escherichia coli enterotoxin are potent mucosal adjuvants but frequently cause secondary effects, such as severe diarrhea and induction of Th2 responses that can lead to undesirable immune responses (21). Although various IL-12 delivery systems based on retroviral vectors and gene gun techniques have been described (38, 40, 49), an efficient and cost-effective means of delivery remains to be developed.

The gram-positive and nonpathogenic lactic acid bacteria are considered promising candidates for the development of oral live vaccines. Lactococcus lactis, the model lactic acid bacterium, has been extensively engineered for the production of heterologous proteins (5, 13, 16, 35), including some antigens of bacterial or viral origin (5, 13, 33). L. lactis is of particular interest for oral delivery of functional proteins since it is a noncommensal, food bacterium that does not survive in the digestive tracts of animal models and humans (12, 16). In the case of IL-12 cytokine delivery, these properties could ensure transient expression of the protein, thereby limiting the risks of toxicity.

IL-12 production requires assembly of two subunits involving two disulfide bonds (DSB) (47). In gram-negative bacteria, DSB mediate protein folding during export; however, the final destination of exported proteins is the periplasm. In contrast, DSB formation is poorly documented in gram-positive bacteria. Only a few extracytoplasmic proteins with DSB have been identified, and to our knowledge, exported heterologous proteins containing DSB have been reported only in Bacillus subtilis (44, 46). However, in contrast to gram-negative bacteria, protein secretion in gram-positive bacteria leads to release of the protein into the medium, which provides an immediate advantage for a delivery system. Until now, secretion of a heterologous protein containing DSB by L. lactis has not been reported. In this study we demonstrated the capacity of L. lactis to produce and secrete a biologically active form of IL-12, a complex two-subunit cytokine with two DSB that are essential for its activity (47). We found that IL-12-producing recombinant L. lactis strains induce IFN-γ production in splenocyte cultures and after intranasal administration in mice.

Additionally, the potential adjuvant properties of an L. lactis strain secreting IL-12 were examined in combination with the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) E7 antigen. This antigen, which has been implicated in the progression of cervical cancer, is considered a potential candidate antigen for anticancer vaccine development. One drawback for its use is its poor induction of a cellular immune response (42). Administration of an L. lactis strain displaying a cell wall-anchored HPV-16 E7 antigen was significantly enhanced after coadministration of an L. lactis strain secreting IL-12 protein, corroborating the hypothesis that the recombinant strain described here is a promising candidate for mucosal codelivery of proteins of medical interest. This work marks a new step in the development of live protein presentation systems for nasal and/or oral administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. L. lactis was grown in M17 medium supplemented with 1% glucose or in brain heart infusion at 30°C without agitation. Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. Unless otherwise indicated, plasmid constructs were first established in E. coli and then transferred to L. lactis by electrotransformation (32, 51). Plasmids were selected by addition of antibiotics, as follows: 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml for L. lactis, 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml for E. coli, and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml for E. coli.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Replicon | Genotype or characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| E. coli TG1 | supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′(traD36 proAB+lacI lacZΔM15) | 19 | |

| L. lactis MG1363 | Wild type, plasmid free | 14 | |

| L. lactis NZ9000 | MG1363 (nisRK genes in chromosome), plasmid free | 30 | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pWRG3169 | ColE1 | Apr, pBS derivative containing coding sequences for p35 and p40 subunits | 49 |

| pCR:TOPO | ori pUC | Apr | Invitrogen |

| pCR-TOPO:Δp35exon1 | ori pUC | Apr, DNA fragment encoding first exon of p35 subunit devoid of its SP | This study |

| pCR-TOPO:p35exon2 | ori pUC | Apr, DNA fragment encoding second exon of p35 subunit | This study |

| pCR-TOPO:Δp35 | ori pUC | Apr, DNA fragment encoding p35 mature moiety devoid of intron | This study |

| pVE8001 | ColE1 | Apr, pBS derivative containing trpA transcription terminator | 48 |

| pBS:Δp40:trpA | ColE1 | Apr, DNA fragment encoding p40 mature moiety devoid of its SP plus trpA | This study |

| pVE8022 | ColE1/pAMβ | Apr Emr, pFUN derivative containing Exp4-ΔSPNuc fusion | 48 |

| pBS:SPExp4 | ColE1 | Apr, PCR fragment encoding SPExp4 SP | This study |

| pBS:SPExp4:p40:trpA | ColE1 | Apr, gene expressed from PnisA encodes SPUsp-p40:trpA p40 subunit precursor | This study |

| pSEC:E7 | pWV01 | Cmr, gene expressed from PnisA encodes SPUsp-E7 precursor | 5 |

| pSEC:p35 | pWV01 | Cmr, gene expressed from PnisA encodes SPUsp-p35 p35 subunit precursor | This study |

| pSEC:p35-p40 | pWV01 | Cmr, gene expressed from PnisA encodes SPUsp-p35-p40 p35 and p40 subunit precursors | This study |

| pCDNA3:IL-12 | ColE1 | Apr, PCR fragment encoding IL-12 single chain | P. Melbya |

| pCR:TOPO:scIL-12 | ori pUC | Apr, PCR fragment encoding scIL-12 single chain devoid of its SP | This study |

| pSEC:scIL-12 | pWV01 | Cmr, gene expressed from PnisA encodes SPUsp-IL-12 single-chain precursor | This study |

The University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

DNA manipulation and methods used.

Plasmid DNA isolation and general procedures for DNA manipulation were performed essentially as described previously (51). PCR amplification was performed with a Perkin-Elmer Cetus (Norwalk, Conn.) apparatus by using Vent DNA polymerase (Promega). DNA sequences were confirmed by using a Dye terminator sequencing kit.

Deletion of an intron in the p35 subunit.

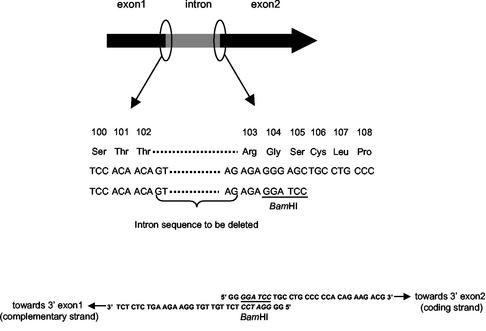

The genes encoding p35 and p40 of murine IL-12 were isolated from pWRG3169, a vector previously described as functional in a eukaryotic system (kindly provided by Alexander Rakhmilevich) (Table 1) (49). Sequence analysis of pWRG3169 revealed an intron in the p35 subunit (data not shown). As introns are spliced in mammalian cells but not in prokaryotes, directed mutagenesis by PCR was performed to remove the p35 intron (Fig. 1). Briefly, the two exons were PCR amplified, subcloned into a pCR-TOPO kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and ligated to generate a DNA segment encoding the p35 mature moiety devoid of the intron and of its signal peptide (SP) (Δp35). The first exon was amplified by using primer 5′-p35-start (5′-GATGCATCAGAGAGGGTCATTCCAGTCTCTGGA-3′) for the coding strand and primer 5′-p35 (5′-GGGGATCCTCTTGTTGTGGAAGAAGTCTCTCT-3′) for the complementary strand (Fig. 1). The second exon was amplified by using primer 3′-p35 (5′-GGGGATCCTGCCTGCCCCCACAGAAGACG-3′) for the coding strand and primer 3′-p35-stop (5′-GGAATTCTCAGGCGGAGCTCAGATAGCCCA-3′) for the complementary strand (Fig. 1). The primers flanking the intron sequence were designed so that a BamHI site was introduced without modifying the amino acid sequence. The two exons were cloned into pCR-TOPO, resulting in pCR-TOPO:Δp35exon1 and pCR-TOPO:p35exon2, respectively. The fragment encoding p35exon2 was then isolated from BamHI/XbaI-blunted pCR-TOPO:p35exon2 and ligated to BamHI/SmaI-cut pCR-TOPO:Δp35exon1, resulting in pCR-TOPO:Δp35. This final plasmid encodes the unmodified p35 subunit of IL-12.

FIG. 1.

Site-specific mutagenesis. The p35 intron was eliminated by site-directed mutagenesis. Briefly, we inserted a BamHI restriction site (underlined) in the three codons (encoding Arg, Gly, Ser) to the right of the intron. Primers were designed to PCR amplify two fragments of p35 that were joined at the BamHI site, such that p35 was reconstituted but intron free.

Construction of the L. lactis strain producing the p35 and p40 subunits.

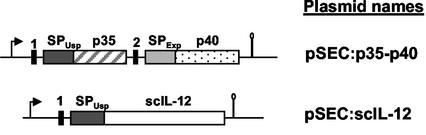

A fragment encoding the p40 mature sequence devoid of its SP (p40) was PCR amplified from plasmid pWRG3169 and subcloned into HincII-cut pVE8001 (Table 1) (kindly provided by Isabelle Poquet, Unité de Recherches Laitières et de Génétique Appliquée, INRA, Jouy en Josas, France), resulting in pBS:Δp40:trpA. The pVE8001 vector has a transcriptional terminator (trpA) and has been used previously to express heterologous proteins in L. lactis (5, 48). The primers used were primer 5′-p40 (5′-GATGCATCAGAGATGTGGGAGCTGGAGAAAGAC-3′) for the coding strand and primer 3′-p40 (5′-GGAGCTCCTAGGATCGGACCCTGCAGGGAA-3′) for the complementary strand. Subsequently, different constructs were made in order to fuse prokaryotic lactococcal SPs to p35 and p40 subunits. For the p40 subunit, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified from pVE8022 (a derivative of plasmid pFUN, in which the ΔSPNuc reporter is fused to Exp4, a putative L. lactis secreted protein of unknown function [48]). This fragment contains the ribosome binding site (RBS) and the signal peptide of Exp4 (SPExp4) (48). The primers used were primer 5′-Exp4 (5′-GGGTACCTTAAGGAGATATAAAAATGAA-3′) for the coding strand and primer 3′-Exp4 (5′-GATGCATCATCAGCAAATACAACGGC-3′) for the complementary strand. The PCR product was cloned into HincII-cut pVE8001, resulting in pBS:SPExp4. pBS:SPExp4:p40:trpA was obtained by insertion of the NsiI/KpnI fragment (containing Δp40:trpA) obtained from pBS:Δp40:trpA into NsiI/KpnI-cut pBS:SPExp4. For the p35 subunit, the NsiI/EcoRI fragment (containing Δp35) obtained from pCR-TOPO:Δp35 was cloned into a pSEC backbone purified from NsiI/EcoRI-cut pSEC:E7 (7) (Table 1), resulting in pSEC:p35. In this vector, the p35 gene is fused to the RBS and SPUsp45 of usp45, the gene encoding Usp45, the main secreted protein in L. lactis (59). Expression is controlled by the PnisA inducible promoter, whose expression depends on the nisin concentration used (11, 30). Finally, to obtain the plasmid that expressed both the p35 subunit and the p40 subunit, a KpnI/BamHI-Klenow cassette encoding SPExp4:p40:trpA was isolated from the pBS:SPExp4:p40:trpA vector and cloned into the KpnI/SmaI-cut pSEC:p35 backbone, resulting in pSEC:p35-p40 (Table 1) (Fig. 2). This vector, in which the two subunits were transcribed from the PnisA promoter, was established in L. lactis NZ9000 carrying the regulatory genes nisR and nisK (30). The resulting strain is referred to below as NZ(pSEC:p35-p40).

FIG. 2.

Expression cassettes to produce and secrete IL-12 in L. lactis: schematic structures of p35 and p40 subunits and scIL-12 cassette expressed under the lactococcal PnisA promoter and carried by the plasmids indicated. For details concerning plasmid construction, see the text and Table 1. The arrows indicate the presence of the nisin-inducible promoter (PnisA); the solid vertical bars indicate the RBS of the usp45 gene (bar 1 for p35) or of the exp4 gene (bar 2 for p40); the dark gray bars indicate the SP of the usp45 gene; the light gray bar indicates the SP of the exp4 gene (48); the cross-hatched bar indicates the p35 mature coding sequence; the dotted bar indicates the p40 mature coding sequence; the open bar indicates the scIL-12 coding sequence; and the stem-loop symbols indicate trpA transcription terminators (not to scale).

Construction of an L. lactis strain with an scIL-12 gene.

A single-chain IL-12 (scIL-12) gene (scIL-12) was amplified by PCR from plasmid pCDNA3:IL-12 (kindly provided by Peter Melby, The University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). The primers used were primer 5′-IL-12 (5′-GATGCATCAGAGATGTGGGAGCTG GAGAAAGAC-3′) for the coding strand and primer 3′-IL-12 (5′-GGAATTCTCAGGCGGAGCTCAGATAGCCCA-3′) for the complementary strand. Primer 5′-IL-12 was designed to delete the first 22 codons in the scIL-12 coding sequence. These codons encode the p40 eukaryotic SP that is replaced by the lactococcal SPUsp45. The PCR product was cloned into pCR:TOPO (Invitrogen), resulting in pCR:TOPO:scIL-12 (Table 1). An scIL-12 cassette was purified from NsiI/NotI-cut pCR:TOPO:scIL-12 and cloned into a pSEC backbone purified from NsiI/NotI-cut pSEC:E7. In the resulting plasmid, pSEC:scIL12 (Table 1 and Fig. 2), the scIL-12 mature moiety was fused in frame with a DNA fragment encoding the RBS and SPUsp45 of usp45. Expression was controlled by a PnisA promoter. This plasmid was established in L. lactis strain NZ9000 to obtain NZ(pSEC:scIL12).

IL-12 expression and detection.

For induction of the nisin promoter, strains were grown until the optical density at 600 nm was ∼0.6, and this was followed by induction with 10 ng of nisin (Sigma) per ml for 1 h. These parameters (amount of nisin and time of induction) were previously determined to be optimal (Bermúdez-Humarán, unpublished data). L. lactis culture extraction and immunoblotting assays were performed as previously described (5, 35); mouse IL-12 antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) were used for immunodetection. The concentration of IL-12 secreted in a culture was estimated by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit that recognized the IL-12 heterodimer but not the individual subunits (R&D Systems).

Preparation of bacterial supernatants for IL-12 nondenaturing analyses.

Supernatant samples from induced cultures were concentrated 50-fold by using an Ultrafree Biomax NMWL membrane. After centrifugation, 10 μl of nondenaturing loading buffer (i.e., buffer lacking dithiothreitol and sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) was added to 10 μl of supernatant concentrate. Electrophoresis was performed as described by Laemmli (31), except that SDS was omitted from all solutions.

Animals.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). The mice were housed in the animal facility at the Immunology and Virology Laboratory at the University of Nuevo León, San Nicolás de los Garza, Mexico. Experiments were performed by using protocols approved by the animal studies committee.

Preparation of bacterial cells for IL-12 biological activity assays.

Twenty milliliters of an induced culture was centrifuged, and the pellet and supernatant were separated. The bacterial cells were washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS. The supernatant was concentrated 100-fold by using an Ultrafree Biomax NMWL membrane in 200 μl (final volume) of PBS.

In vitro IFN-γ detection.

Spleens were obtained from four mice that were 6 to 8 weeks old, and splenocytes were separated on a Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma) density gradient. A preparation containing 2 × 106 cells/ml in AIM-V medium (GIBCO) was plated on a 24-well plate (2 ml per well) at 37°C under 5% CO2. As a positive control, mouse splenocytes were incubated with 50 pg of recombinant IL-12 (rIL-12) (R&D Systems). Splenocytes were incubated with 10 μl of recombinant L. lactis cells or with culture supernatant samples that were adjusted beforehand to provide ∼50 pg per sample, as determined by an ELISA. Supernatants from the treated splenocytes were harvested after 48 h and tested for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's directions. All samples were prepared in triplicate.

Intranasal administration of recombinant L. lactis strains encoding IL-12.

Groups of three mice that were 6 to 8 weeks old were inoculated intranasally with recombinant or wild-type L. lactis or with PBS. Prior to treatment, the mice were partially anesthetized intraperitoneally with a combination of Xilacyne and Ketamine (0.40 ml per 20 lb; Cheminova de México, Mexico). A total of 5 × 108 CFU (prepared as described above) of each induced L. lactis strain was resuspended in 10 μl of PBS, and 5 μl was administered with a micropipette into each nostril on days 0, 14, and 28.

IFN-γ induction assay.

Animals treated with recombinant L. lactis strains were sacrificed on day 35. Splenocytes were separated and cultured as described above. Mouse cells were stimulated in vitro with 50 μl of phytohemagglutinin (5 μg/ml; M form, a polyclonal activator; GIBCO) to increase the proliferative response and to mimic a situation in which IFN-γ is induced. Supernatants from the treated splenocytes were harvested after 24 h and tested for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA (R&D Systems). All samples were prepared in triplicate.

Coadministration of L. lactis strains expressing HPV-16 E7 and IL-12.

In order to confirm the ability of an L. lactis strain to secrete IL-12 and to enhance an antigen-specific T-cell response, we used the HPV-16 E7 protein as an antigen. This protein was successfully expressed previously in L. lactis (5). Groups of three mice were immunized (as described above) with 5 × 108 CFU of an L. lactis strain displaying a cell wall-anchored E7 antigen [NZ(pCWA-E7) (Cortes-Perez, unpublished data)] alone or in combination with 5 × 108 CFU of strain NZ(pSEC:scIL12). A control group received the wild-type L. lactis strain. Splenocytes from immunized animals were used for detection of IL-2 and IFN-γ, cytokines characteristic of a Th1 type of immune response (17, 24, 53).

Determination of Th1 cytokine production in splenocytes.

Mice immunized with L. lactis strains were sacrificed on day 35. Splenocytes were separated and cultured as described above. Cell suspensions from each different treatment were cultured with 2 μg of a synthetic E7 peptide (positions 49 to 57; RAHYNIVTF) to determine whether in vitro restimulation induced a peptide-specific (i.e., antigen-specific) cellular response or with PBS alone as a control. After 24 h, cell suspensions were filtered, and supernatants were tested for the presence of IL-2 and IFN-γ by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Statistics.

Student's t test was performed by using MINITAB, a computer software package (Minitab Inc., State College, Pa.).

RESULTS

p35 and p40 subunits are secreted and correctly processed by L. lactis.

The ability of L. lactis to secrete the two IL-12 subunits was tested by using strain NZ(pSEC:p35-p40). Cultures of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) were harvested after induction (final optical density at 600 nm, ∼1). Expression and secretion of the p40 and p35 subunits were analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-IL-12 antiserum (Fig. 3). Protein samples were prepared for cell and supernatant fractions. A pattern of diverse molecular weight forms was obtained for the cell fraction of induced cells, suggesting that there was accumulation of p40 and p35 precursors, as well as proteolysis in the cytoplasm or at the cell surface (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the supernatant fraction produced two distinct bands that migrated at the sizes expected for p35 and p40 (Fig. 3A). For both subunits, the secretion efficiency (i.e., the proportion of the mature form secreted into the supernatant) was low (<15%). Western analyses were performed with noninduced recombinant L. lactis strains, and no IL-12 production was detected (data not shown). The approximately equal intensities of the two subunits suggest that the subunits are produced in the proper stoichiometry to form an active IL-12 heterodimer. These results demonstrate that L. lactis is able to produce and secrete both IL-12 subunits.

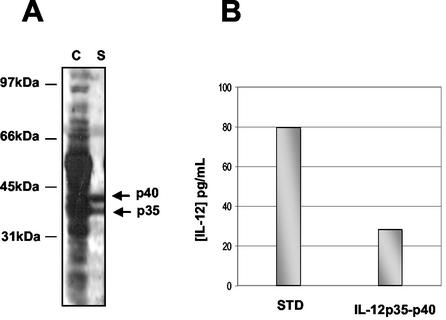

FIG. 3.

Production of IL-12 by recombinant L. lactis. IL-12 production was analyzed by immunoblotting by using anti-IL-12 antibodies. Protein samples were prepared from induced recombinant L. lactis cultures. (A) Immunodetection after SDS-PAGE. Lane C, cell fraction of the NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) strain encoding the p35 and p40 subunits (IL-12p35-p40); lane S, supernatant samples. The positions and sizes of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (B) Quantification of IL-12p35-p40 by ELISA (R&D Systems). STD, 80 pg of commercial murine rIL-12 per ml; IL-12p35-p40, supernatant sample of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) culture.

We tested the capacity of L. lactis to produce and secrete IL-12p35-p40 in its assembled heterodimeric form. Protein samples were prepared from induced NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) cultures and analyzed by immunoblotting by using anti-IL-12 antiserum after polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under nondenaturing conditions. A band that comigrated with the IL-12 control was detected in NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) supernatant (data not shown). This band could have corresponded to IL-12 or to a p40 homodimer. A p40 subunit may indeed associate with another p40 subunit to form a homodimer (p402) with a molecular mass of 80 kDa. A p402 form reportedly is an antagonist of IL-12 in vitro (37). To determine whether this high-molecular-weight form corresponds to the assembled form of IL-12, culture supernatants of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) induced for IL-12 synthesis were analyzed by an ELISA that is specific for quantification of native murine IL-12p35-p40 (61). The concentration of secreted IL-12p35-p40 was estimated to be 25 pg/ml (Fig. 3B), compared to 80 pg/ml for an rIL-12 standard. ELISA were also performed with noninduced recombinant L. lactis strains, and no IL-12 production was detected (data not shown). Altogether, these results show that (i) L. lactis is able to secrete both p35 and p40 subunits and (ii) at least a proportion of these subunits is properly assembled in the supernatant.

Production of IL-12 as a single-chain polypeptide in L. lactis.

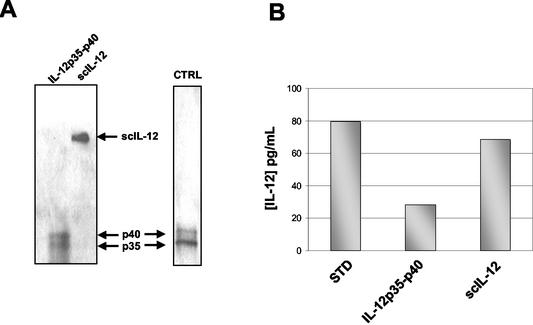

One way to favor proper assembly of the p35 and p40 subunits is to synthesize a fusion protein comprising the two polypeptides. This strategy has already been proven to be efficient in eukaryotic systems (15). Expression of scIL-12 was tested in L. lactis by using strain NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) and was compared to expression in NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) (Fig. 4A). Induced culture samples were prepared as described above. After induction, Western blot analysis with anti-IL-12 antibody revealed a clear band in the supernatant at the expected size for scIL-12 (70 kDa). The amount of secreted scIL-12 was found to be two- to threefold larger than the amounts of the separate p35 and p40 subunits (Fig. 4A). We also measured the scIL-12 concentration in the supernatant using the ELISA that recognized IL-12 only in the native conformation. The amount of scIL-12 was found to be twofold larger than the amounts of the p35 and p40 subunits (∼65 pg/ml for scIL-12 and ∼25 pg/ml for IL-12p35-p40) (Fig. 4B). Western blotting and ELISA were performed with noninduced recombinant L. lactis strains, and no IL-12 production was detected (data not shown). This result shows that scIL-12 is efficiently secreted in L. lactis and is folded into a native conformation. The results described above show that both IL-12p35-p40 and scIL-12 are expressed and secreted in L. lactis and suggest that at least portions of these products assume a native and thus potentially active form.

FIG. 4.

Secretion analysis of the two IL-12 forms produced by L. lactis. (A) rIL-12 production compared by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of supernatant samples prepared from induced cultures of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) and NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) encoding IL-12p35-p40 and scIL-12, respectively. Lane CTRL contained rIL-12 (R&D Systems) as a control. (B) Quantification of IL-12 forms produced by L. lactis by ELISA by using supernatants of induced cultures of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) and NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) encoding IL-12p35-p40 and scIL-12. STD, 80 pg of commercial rIL-12 per ml.

Biological activity of IL-12 produced by recombinant L. lactis.

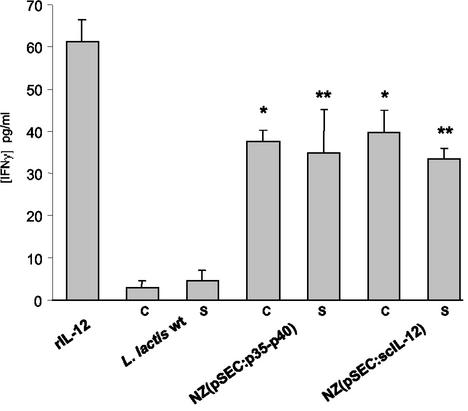

Recombinant L. lactis strains producing IL-12p35-p40 and scIL-12 were evaluated for the ability to induce IFN-γ production in mouse splenocytes. Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h with 50 pg of commercial rIL-12 per ml or with supernatant or a total culture of recombinant L. lactis. The amounts of bacterially produced IL-12 added to splenocytes were adjusted to ∼50 pg/ml as determined by the quantitative ELISA. After in vitro IL-12 stimulation, splenocyte culture supernatants were collected to measure the concentrations of IFN-γ (Fig. 5). The results show that 50 pg of commercial rIL-12 per ml induced production of ∼60 pg of IFN-γ per ml. The scIL-12 produced by 5 × 108 CFU of L. lactis induced production of ∼40 pg/ml, and supernatants of the same cells induced production of ∼33 pg/ml. The concentrations of IFN-γ induced by an L. lactis strain expressing p35-p40 were ∼37 pg/ml for 1 × 109 CFU and ∼34 pg/ml for the supernatant. Splenocytes in the presence of a wild-type L. lactis strain did not produce significant amounts of IFN-γ, as expected (Fig. 5). These results suggest that both scIL-12 and IL-12p35-p40 are biologically active and stimulate IFN-γ production by mouse splenocytes.

FIG. 5.

In vitro induction of IFN-γ in mouse splenocytes by recombinant L. lactis. Mouse splenocytes were incubated in the presence of 50 μg of rIL-12 per ml as a control and with cells (C) and supernatant (S) of wild-type L. lactis (L. lactis wt), L. lactis NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) IL-12p35-p40, or L. lactis NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) encoding scIL-12. The concentrations of the induced culture samples were adjusted to ∼50 pg/ml as determined by ELISA. The IFN-γ concentrations are the means and standard deviations determined in three independent experiments. Significant differences compared to the data obtained for recombinant L. lactis cells and supernatant samples are indicated by one asterisk and two asterisks, respectively (P < 0.05).

Intranasal administration of L. lactis expressing IL-12 induces IFN-γ production in mouse splenocytes.

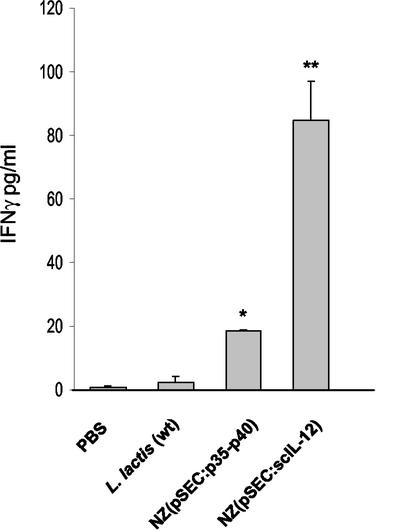

The biological activities of the IL-12-producing L. lactis strains were also tested in vivo after intranasal administration of induced recombinant L. lactis strains in mice. It has been shown previously that a regimen consisting of intranasal administration of IL-12 on days 0, 1, 2, and 3 with booster doses on days 14 and 28 (and repeating the schedule for four inoculations) and sacrifice of the animals on day 35 results in an absence of cytokine toxicity in a murine model (3). However, although this treatment schedule is very productive in mice, its use in human vaccination is limited due to the consecutive IL-12 inoculations during the treatment. To avoid this problem, in this experiment we tested single doses of IL-12-expressing L. lactis strains administered on days 0, 14, and 28. We administered 5 × 108 CFU of NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) or NZ(pSEC:scIL-12), which corresponds to quantities used previously for oral administration of recombinant L. lactis (50).

IFN-γ expression was significantly enhanced in mice that received L. lactis strains expressing IL-12p35-p40 or scIL-12 compared to IFN-γ expression in the placebo control groups (Fig. 6). Mice treated with the scIL-12-producing strain produced the largest amounts of IFN-γ in spleen cells. In contrast, the amounts of IFN-γ in mice treated with the p35-p40-producing strain were fourfold smaller. The differences in the degree of stimulation were probably due to the quantity of native IL-12 produced under the conditions used (Fig. 3 and 4). This experiment was repeated three times, and similar results were obtained in all cases. The results demonstrated that IL-12 can be effectively administered to mice in vivo by using recombinant L. lactis, which results in clear induction of the IFN-γ response. Furthermore, after intranasal administration of the L. lactis IL-12-producing strains, IFN-γ production was induced without apparent toxicity, and mice remained healthy after 24 weeks of treatment.

FIG. 6.

Production of IFN-γ in mouse splenocytes after intranasal inoculation of recombinant L. lactis. Levels of IFN-γ were determined following sacrifice on day 35 for mice that received 5 × 108 CFU of wild-type L. lactis [L. lactis (wt)], NZ(pSEC:p35-p40), or NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) or PBS alone. The data are representative of one of three separate experiments in which similar results were obtained. The values are the means and standard deviations for three mice per treatment group. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared with the wild-type L. lactis and PBS control groups are indicated by one asterisk for the NZ(pSEC:p35-p40) group and by two asterisks for NZ(pSEC:scIL-12) group.

Because the concentrations of functional IL-12 measured in both in vitro and in vivo assays were greater for scIL-12 than for the two-subunit IL-12 form, we chose the single-chain form for the next in vivo experiment.

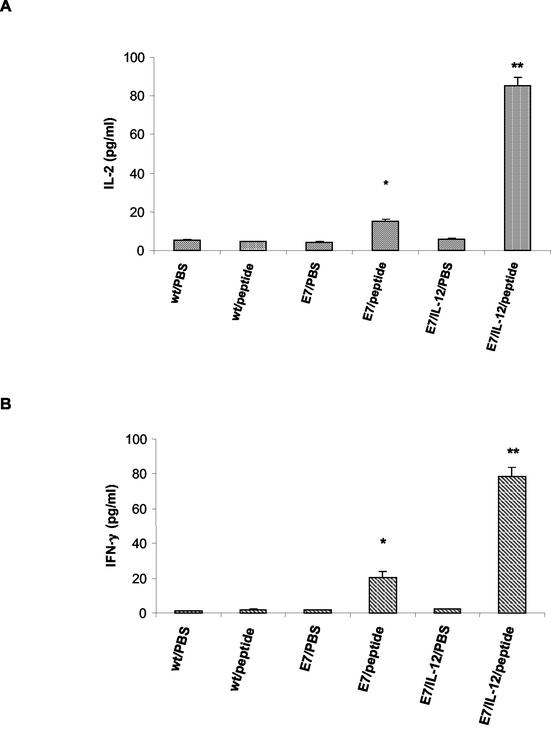

Intranasal coadministration of recombinant L. lactis strains expressing active IL-12 and HPV-16 E7 enhanced IFN-γ production.

In order to examine the adjuvant properties of the recombinant L. lactis strain producing IL-12, the immune response to a coadministered antigen was analyzed. The antigen that was coexpressed with IL-12 was the HPV-16 E7 protein, the major worldwide etiological agent of cervical cancer. Groups of five C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with three doses (on days 0, 14, and 28) of 5 × 108 CFU of NZ(pCWA-E7) alone or in combination with 5 × 108 CFU of NZ(pSEC:scIL12). The production of IL-2 and IFN-γ was then determined (Fig. 7). Spleen cells that were obtained 1 week after the last inoculation with recombinant L. lactis (day 35) and were restimulated in vitro with a synthetic E7 peptide (RAHYNIVTF) produced significant levels of IL-2 (Fig. 7A) and IFN-γ (Fig. 7B). As an in vitro control, spleen cells were restimulated with PBS alone. The responses were greater in mice immunized with an L. lactis strain displaying a cell wall-anchored E7 antigen than in animals immunized with a wild-type L. lactis strain. Strikingly, the antigen-specific cellular response measured by secretion of Th1 cytokines elicited by L. lactis expressing E7 antigen alone was dramatically increased by coadministration with an L. lactis strain secreting IL-12 protein (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Production of Th1 cytokines by splenocytes of mice immunized with recombinant L. lactis. Levels of Th1 cytokines were determined following sacrifice on day 35 for mice immunized with 5 × 108 CFU of wild-type L. lactis (wt) or recombinant L. lactis displaying E7 antigen (E7) and for mice coimmunized with L. lactis displaying E7 and an L. lactis strain secreting active murine IL-12 (E7/IL-12). Spleen cells were cultured for 24 h with 2 μg of E7 peptide (RAHYNIVTF) (peptide) or PBS, and the levels of the Th1 cytokines IL-2 (A) and IFN-γ (B) in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. The values are the means and standard deviations for three mice per treatment group. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the E7/PBS group are indicated by one asterisk and by two asterisks for the E7/peptide and E7/IL-12/peptide groups, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we produced bioactive forms of IL-12 in the food-grade gram-positive bacterium L. lactis, and we showed that the recombinant bacterium has a stimulatory effect on IFN-γ production in both in vitro and in vivo assays. Previous reports of IL-12 production involved the use of eukaryotic systems (15, 29, 52, 57), which may have limitations in broad-scale or in vivo applications. Recently, Steidler et al. demonstrated that L. lactis could be used to produce and secrete biologically active murine monomeric cytokines (55, 56). The production of a more complex molecule (i.e., a heterodimer that contains several DSB) further extends the potential of L. lactis to deliver therapeutic molecules in vivo.

IL-12 is a heterodimer composed of two distinct subunits (p35 and p40) encoded by separate genes that are coordinately expressed. Previous studies have demonstrated that p40 overexpression can have an inhibitory effect on IL-12 activity (37). We used two approaches to overcome this potential problem. First, we developed a bicistronic cassette for coexpression of p35 and p40 subunits in L. lactis. Second, we designed a vector that expressed IL-12 as a single-chain polypeptide, thus allowing stoichiometric formation of this cytokine. This strategy also overcomes problems with inefficient association of independently produced subunits or formation of homodimers (20, 37). Consistent with this hypothesis, under equivalent induction conditions, the concentrations of functional IL-12 were greater for scIL-12 than for the two-subunit IL-12 form. In view of the lower activities of p35 and p40, the single-chain form of IL-12 may be preferred for in vivo applications.

Remarkably, mouse IL-12 contains 7 and 13 cysteines in its p35 and p40 subunits, respectively, and two DSB that are essential for proper IL-12 assembly (47). The secretion of biologically active IL-12 suggests that DSB are formed after the protein is exported from L. lactis. DSB formation is often a major bottleneck in heterologous protein production in prokaryotic systems and particularly in gram-positive bacteria, which themselves encode very few secreted proteins that contain DSB (44, 46). Possibly, the lower pH of L. lactis during fermentative growth favors formation of DSB in secreted proteins. Although the mechanism remains to be proven, this system may be promising for expression of other proteins containing DSB.

The main biological effect of IL-12 is stimulation of IFN-γ production. This cytokine has both adjuvant and antitumor activities. Because a number of subunit vaccines are poorly immunogenic, the use of adjuvants is of particular interest for new formulations of vaccines against infectious diseases. To enhance the mucosal immune response, adjuvants such as cholera toxin and E. coli enterotoxin have been used, and they indeed induce potent Th1 and Th2 cell responses. However, these adjuvants cause severe diarrhea and are not suitable for use as mucosal adjuvants in humans. Strikingly, IL-12 has proven adjuvant activity when it is coexpressed with an antigen in targeted vaccines (1, 6). It may also prevent the development of immunological tolerance to a given antigen (54). Finally, IL-12 has potent antitumor effects and may be an attractive agent for cancer immunotherapy.

Despite the efficacy of IL-12 therapy for cancer and infectious diseases, experimental models in clinical trials with systemic IL-12 showed unacceptable levels of toxicity related to elevated IFN-γ production (9, 36). The limitations of IL-12 treatment include the need for daily administration (27). Here, to circumvent this problem, we explored mucosal (intranasal) delivery of active IL-12 by using the safe vector L. lactis, which repeatedly has been reported to be noninvasive and noncolonizing in a murine model (12, 16, 22). Recently, a recombinant L. lactis strain delivering IL-10 via an oral route exhibited positive effects during treatment of murine colitis. The dose of IL-10 given orally was estimated to be 10-fold lower than the dose required for systemic administration (56). Targeted administration of other interleukins, such as IL-12, to the intestinal tract by food-grade L. lactis may also reduce toxicity and have advantages compared to treatment by the systemic route, and it may even maximize the response (39).

There is continual interest in developing mucosally based vaccines for a variety of different pathogens, including HPV. The use of live oral delivery systems for tumor therapy or vaccine delivery may thus reduce toxic side effects resulting from systemic administration. In this study, we showed the adjuvant effect of a recombinant L. lactis strain producing IL-12 protein which enhanced the mucosal immune responses against a coadministered antigen. The IL-2 and IFN-γ production elicited by a recombinant L. lactis strain displaying a cell wall-anchored HPV-16 E7 antigen was dramatically increased by coadministration with an L. lactis strain secreting IL-12 protein.

It is well established that IL-12 plays an essential role in switching of the immune response, inducing Th1 cells and suppressing Th2 responses (58). On the other hand, the elevated density of Th2 cells during the pathogenesis of advanced cervical cancer is well known, while the level of Th1 cells is dramatically diminished (2, 18). We believe that successful immunotherapeutic treatments of cervical cancer patients will use a vaccine that will be able to switch the immune response from the Th2 class to the Th1 class. Therefore, on the basis of this belief, an L. lactis strain modified to secrete IL-12 together with a specific antigen is a good candidate for cervical cancer therapy.

In summary, for vaccine applications, oral or nasal delivery may provoke local immune responses at the portal of entry of most pathogens. The use of L. lactis to deliver IL-12 to a mucosal surface (e.g., the intranasal surface, gut, or vaginal mucosa) may have clear advantages over a systemic therapy approach because it reduces toxic side effects and provides a low-cost, simple method of administration.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jorge Gómez for his technical assistance. We thank Isabelle Poquet for critical reading of the manuscript and the members of the URLGA laboratory for helpful suggestions during this work.

This work was in part supported by grants from PAICYT and CONACYT, Mexico. L.G.B.-H. and N.G.C.-P. are the recipients of fellowships from CONACyT, Mexico.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso, L. C., T. M. Scharton, L. Q. Vieira, M. Wysocka, G. Trinchieri, and P. Scott. 1994. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science 263:235-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.al-Saleh, W., S. L. Giannini, N. Jacobs, M. Moutschen, J. Doyen, J. Boniver, and P. Delvenne. 1998. Correlation of T-helper secretory differentiation and types of antigen-presenting cells in squamous intraepithelial lesions of the uterine cervix. J. Pathol. 184:283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arulanandam, B. P., M. O'Toole, and D. W. Metzger. 1999. Intranasal interleukin-12 is a powerful adjuvant for protective mucosal immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 180:940-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth, H., R. Klein, P. A. Berg, B. Wiedenmann, U. Hopf, and T. Berg. 2001. Induction of T helper cell type 1 response and elimination of HBeAg during treatment with IL-12 in a patient with therapy-refractory chronic hepatitis B. Hepatogastroenterology 48:553-555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., P. Langella, A. Miyoshi, A. Gruss, R. S. Tamez-Reyes, R. Montes de Oca-Luna, and Y. Le Loir. 2002. Production of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:917-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyaka, P. N., and J. R. McGhee. 2001. Cytokines as adjuvants for the induction of mucosal immunity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 51:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunda, M., L. Luistro, R. Warrier, R. Wright, B. Hubbard, M. Murphy, S. Wolf, and M. K. Gately. 1993. Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of interleukin 12 against murine tumors. J. Exp. Med. 178:1223-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, S. H., B. Perussia, J. W. Grupta, M. Kobayashi, M. Pospisil, H. A. Young, S. G. Wolf, D. Young, S. C. Clark, and G. Trinchieri. 1991. Induction of interferon gamma production by natural killer cell stimulatory factor: characterization of the responder cells and synergy with other inducers. J. Exp. Med. 173:869-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, B., T. M. Timiryasova, D. S. Gridley, M. L. Andres, R. Dutta-Roy, and I. Fodor. 2001. Evaluation of cytokine toxicity induced by vaccinia virus-mediated IL-2 and IL-12 antitumour immunotherapy. Cytokine 15:305-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen, J. 1995. IL-12 deaths: explanation and a puzzle. Science 270:908.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Ruyter, P. G., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3662-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drouault, S., G. Corthier, S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Renault. 1999. Survival, physiology, and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in the digestive tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4881-4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enouf, V., P. Langella, J. Commissaire, J. Cohen, and G. Corthier. 2001. Bovine rotavirus nonstructural protein 4 produced by Lactococcus lactis is antigenic and immunogenic. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1423-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic acid streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaucher, D., and K. Chadee. 2001. Molecular cloning of gerbil interleukin 12 and its expression as a bioactive single-chain protein. Cytokine 14:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geoffroy, M. C., C. Guyard, B. Quatannens, S. Pavan, M. Lange, and A. Mercenier. 2000. Use of green fluorescent protein to tag lactic acid bacterium strains under development as live vaccine vectors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:383-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gherardi, M. M., J. C. Ramirez, and M. Esteban. 2000. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) enhancement of the cellular immune response against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env antigen in a DNA prime/vaccinia virus boost vaccine regimen is time and dose dependent: suppressive effects of IL-12 boost are mediated by nitric oxide. J. Virol. 74:6278-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghim, S. J., J. Sundberg, G. Delgado, and A. B. Jenson. 2001. The pathogenesis of advanced cervical cancer provides the basis for an empirical therapeutic vaccine. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 71:181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, T. J. 1984. Ph.D. thesis. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England.

- 20.Gillessen, S., D. Carvajal, P. Ling, F. J. Podlaski, D. L. Stremlo, P. C. Familletti, U. Gubler, D. H. Presky, A. S. Stern, and M. K. Gately. 1995. Mouse interleukin-12 (IL-12) p40 homodimer: a potent IL-12 antagonist. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham, B. S., G. S. Henderson, Y. W. Tang, X. Lu, K. M. Neuzil, and D. G. Colley. 1993. Priming immunization determines T helper cytokine mRNA expression patterns in lungs of mice challenged with respiratory syncytial virus. J. Immunol. 151:2032-2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grangette, C., H. Muller-Alouf, M. Geoffroy, D. Goudercourt, M. Turneer, and A. Mercenier. 2002. Protection against tetanus toxin after intragastic administration of two recombinant lactic acid bacteria: impact of strain variability and in vivo persistence. Vaccine 20:3304-3309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gubler, U., A. O. Chua, D. S. Schoenhaut, C. M. Dwyer, W. McComas, R. Motyka, N. Mabavi, A. G. Wolitzky, P. M. Quinn, P. C. Familletti, and M. K. Gately. 1991. Coexpression of two distinct genes is required to generate secreted bioactive cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4143-4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoover, D. L., R. M. Crawford, L. L. Van De Verg, M. J. Izadjoo, A. K. Bhattacharjee, C. M. Paranavitana, R. L. Warren, M. P. Nikolich, and T. L. Hadfield. 1999. Protection of mice against brucellosis by vaccination with Brucella melitensis WR201(16MDeltapurEK). Infect. Immun. 67:5877-5884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hultgren, O. H., M. Stenson, and A. Tarkowski. 2001. Role of IL-12 in Staphylococcus aureus-triggered arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis Res. 3:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson, M. A., D. Hardy, E. Connick, J. Watson, and M. DeBruin. 2000. Phase 1 trial of a single dose of recombinant human interleukin-12 in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with 100-500 CD4 cells/microl. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1070-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang, C., D. M. Magee, and R. A. Cox. 1999. Construction of a single-chain interleukin-12-expressing retroviral vector and its application in cytokine gene therapy against experimental coccidioidomycosis. Infect. Immun. 67:2996-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi, M., L. Fitz, M. Ryan, R. M. Hewick, S. C. Clark, S. Chang, R. Koudon, F. Sherman, B. Perussia, and G. Trinchieri. 1989. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 170:827-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokuho, T., S. Watanabe, Y. Yokomizo, and S. Inumaru. 1999. Production of biologically active, heterodimeric porcine interleukin-12 using a monocistronic baculoviral expression system. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 72:289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuipers, O. P., P. G. de Ruyter, M. Kleerebezen, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. Quorum sensing-controlled gene expression in lactic acid bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 64:15-21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langella, P., Y. Le Loir, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1993. Efficient plasmid mobilization by pIP501 in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. J. Bacteriol. 175:5806-5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, M. H., Y. Roussel, M. Wilks, and S. Tabaqchali. 2001. Expression of Helicobacter pylori urease subunit B gene in Lactococcus lactis MG1363 and its use as a vaccine delivery system against H. pylori infection in mice. Vaccine 19:3927-3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, S., M. Zheng, S. Deshpande, S. K. Eo, T. A. Hamilton, and B. T. Rouse. 2002. IL-12 suppresses the expression of ocular immunoinflammatory lesions by effects on angiogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:469-476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Loir, Y., A. Gruss, S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Langella. 1998. A nine-residue synthetic propeptide enhances secretion efficiency of heterologous proteins in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1895-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leonard, J. P., M. L. Sherman, G. L. Fisher, L. J. Buchanan, G. Larsen, M. B. Atkins, J. A. Sosman, J. P. Dutcher, N. J. Vogelzang, and J. L. Ryan. 1997. Effects of single-dose interleukin-12 exposure on interleukin-12-associated toxicity and interferon-gamma production. Blood 90:2541-2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling, P., M. K. Gately, U. Gubler, A. S. Stern, P. Lin, K. Hollfelder, C. Su, Y.-C. E. Pan, and J. Hakimi. 1995. Human IL-12 p40 homodimer binds to the IL-12 receptor but does not mediate biologic activity. J. Immunol. 154:116-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lui, V. W., L. D. Falo, and L. Huang. 2001. Systemic production of IL-12 by naked DNA mediated gene transfer: toxicity and attenuation of transgene expression in vivo. J. Gene Med. 3:384-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magee, D. M., and R. A. Cox. 1996. Interleukin-12 regulation of host defenses against Coccidioides immitis. Infect. Immun. 64:3609-3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazzolini, G., I. Narvaiza, A. Perez-Diez, M. Rodriguez-Calvillo, C. Qian, B. Sangro, J. Ruiz, J. Prieto, and I. Melero. 2001. Genetic heterogeneity in the toxicity to systemic adenoviral gene transfer of interleukin-12. Gene Ther. 8:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metzger, D. W., R. M. McNutt, J. T. Collins, J. M. Buchanan, V. H. Van Cleave, and W. A. Dunnick. 1997. Interleukin-12 acts as an adjuvant for humoral immunity through interferon-gamma-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1958-1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michel, N., W. Osen, L. Gissmann, T. N. Schumacher, H. Zentgraf, and M. Muller. 2002. Enhanced immunogenicity of HPV 16 E7 fusion proteins in DNA vaccination. Virology 294:47-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nastala, C., H. Edington, T. McKinney, H. Tahara, M. Nalesnik, M. Brunda, M. K. Gately, S. Wolf, R. Schreiber, W. Storkus, and M. Lotze. 1994. Recombinant IL-12 administration induces tumor regression in association with IFN-gamma production. J. Immunol. 153:1697-1703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paik, S. H., A. Chakicherla, and J. N. Hansen. 1998. Identification and characterization of the structural and transporter genes for, and the chemical and biological properties of, sublancin 168, a novel lantibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23134-23142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, A. Y., B. Hondowicz, M. Kopf, and P. Scott. 2002. The role of IL-12 in maintaining resistance to Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 168:5771-5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Payne, M. S., and E. N. Jackson. 1991. Use of alkaline phosphatase fusions to study protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:2278-2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Podlaski, F. J., V. B. Nanduri, J. D. Hulmes, Y. C. Pan, W. Levin, W. Danho, R. Chizzonite, M. K. Gately, and A. S. Stern. 1992. Molecular characterization of interleukin 12. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 294:230-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poquet, I., S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1998. An export-specific reporter designed for gram-positive bacteria: application to Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1904-1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rakhmilevich, A. L., J. Turner, M. J. Ford, D. McCabe, W. H. Sun, P. M. Sondel, K. Grota, and N.-Y. Yang. 1996. Gene gun-mediated skin transfection with interleukin 12 gene results in regression of established and metastatic murine tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6291-6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson, K., L. M. Chamberlain K. M. Schofield, J. M. Wells, and R. W. 1997. Oral vaccination of mice against tetanus with recombinant Lactococcus lactis. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 52.Shen, H., C. Li, M. Lin, Z. Zhang, and Q. Shen. 1998. Expression of human interleukin 12 (hIL-12) in insect cells. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 14:205-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sin, J. I., J. J. Kim, R. L. Arnold, K. E. Shroff, D. McCallus, C. Pachuk, S. P. McElhiney, M. W. Wolf, S. J. Pompa-de Bruin, T. J. Higgins, R. B. Ciccarelli, and D. B. Weiner. 1999. IL-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1-type CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus-2 challenge. J. Immunol. 162:2912-2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sinkovics, J. G., and J. C. Horvath. 2000. Vaccination against human cancers. Int. J. Oncol. 16:81-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steidler, L., K. Robinson, L. Chamberlain, K. M. Schofield, E. Remaut, R. W. Le Page, and J. M. Wells. 1998. Mucosal delivery of murine interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-6 by recombinant strains of Lactococcus lactis coexpressing antigen and cytokine. Infect. Immun. 66:3183-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steidler, L., W. Hans, L. Schotte, S. Neirynck, F. Obermeier, W. Falk, W. Fiers, and E. Remaut. 2000. Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10. Science 289:1352-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takehara, K., T. Nagata, R. Kikura, T. Takanashi, S. Yoshiya, and A. Yamaga. 2000. Expression of a bioactive interleukin-12 using baculovirus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 77:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trinchieri, G. 1995. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:251-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Asseldonk, M., G. Rutten, M. Oteman, R. J. Siezen, W. M. de Vos, and G. Simons. 1990. Cloning, expression in Escherichia coli and characterization of usp45, a gene encoding a highly secreted protein from Lactococcus lactis MG1363. Gene 95:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voest, E. E., B. M. Kenyon, M. S. O'Reilly, G. Truitt, R. J. D'Amato, and J. Folkman. 1995. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vivo by interleukin 12. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 19:581-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson, V. L., R. R. Warrier, T. P. Truitt, P. Nunes, M. K. Gately, and D. H. Presky. 1996. Characterization of anti-mouse IL-12 monoclonal antibodies and measurement of mouse IL-12 by ELISA. J. Immunol. Methods 189:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]