Abstract

The events preceding human immunodeficiency virus fusion and entry are influenced by the concentration and distribution of receptor and coreceptor molecules on the cell surface. However, the extent to which these proteins colocalize with one another in the cell membrane remains unclear. Using high-resolution deconvolution fluorescent microscopy of living cells, we found that both CD4 and CCR5 accumulate in protruding membrane structures containing actin and ezrin. Although CD4 and CCR5 extensively colocalize in these structures, they do not exist in a stable complex.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects CD4+ target cells via a specific receptor-mediated fusion event that also requires the participation of a viral coreceptor (reviewed in reference 8). The identification of the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 as the primary coreceptor molecules provided great insight into the mechanism of viral fusion and entry (2, 6, 7, 9). Current models suggest that the initial interaction between the viral envelope protein gp120 and CD4 on target cells results in a conformational change in gp120 that exposes the coreceptor binding site. After binding to the coreceptor molecule, additional structural changes are thought to take place, allowing the viral gp41 protein to initiate the fusion process. Previous studies suggest that multiple receptor and coreceptor molecules are needed to interact with each envelope trimer (8, 12) and that multiple trimers may be necessary for the formation of the fusion pore (14). Thus, cooperative interactions must take place between viral envelope, receptor, and coreceptor proteins in order for viral entry to occur.

The need for these cooperative interactions has brought about considerable debate regarding the extent of association between the CD4 and chemokine receptor molecules in the target cell membrane. Two recent studies have found that the addition of purified gp120 to target cell cultures induces actin-dependent colocalization of CD4 and chemokine receptor in the membrane (11, 16). Others have described a constitutive association between CD4 and chemokine receptors in complexes (22), lipid rafts (16, 18), or specific cell types (13). To gain additional insight into the membrane localization and association of these proteins, we conducted immunofluorescent analysis of CD4 and CCR5 by high-resolution deconvolution microscopy. Deconvolution microscopy permits detailed, quantitative analysis of biological materials. Deconvolution uses computer processing to compensate for distortion caused by the optical path. Through the observation of fluorescent beads, an algorithm is developed which corrects the distortion caused by lenses and removes out-of-focus light. In this way, it is possible to remove the out-of-focus light, like a confocal microscope would do, but without the noise that is a consequence of photomultiplier tubes necessary for confocal detection. Therefore, deconvolution microscopy reveals unparalleled details of cell substructures using fluorescent microscopy. To avoid the dilemma of fixation artifacts, fusion proteins were used, allowing localization to be observed in both live and fixed cells. Fluorescent constructs were created by fusing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) to the cytoplasmic tail of human CD4 (CD4-YFP) in plasmid EYFP-N1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the cytoplasmic tail of human CCR5 (CCR5-CFP and CCR5-GFP [4], respectively, in plasmid pECFP-N1 or pEGFP-N1 [Clontech]).

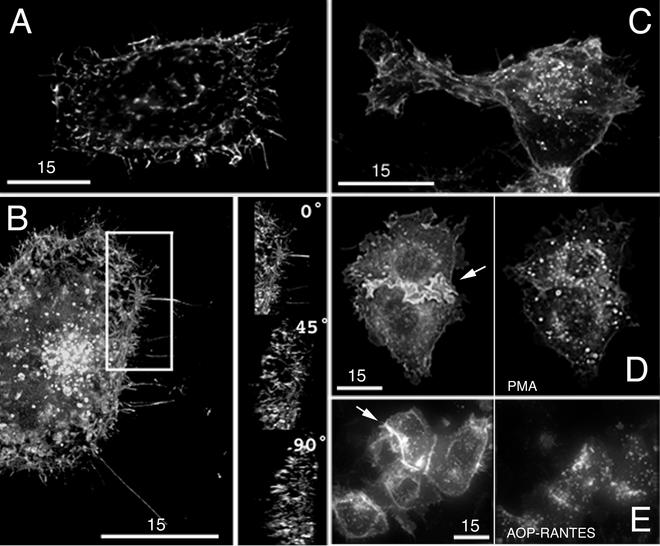

Initial studies were focused on characterization and validation of the fusion proteins to ensure that they were characteristically and functionally similar to the native proteins. Figure 1 shows the localization of native CD4, CD4-YFP, and CCR5-CFP in transfected target cells as observed by deconvolution microscopy. After transfection of HeLa cells with a native CD4 construct, cells were fixed and stained with an anti-CD4 antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and then with a Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.). Interestingly, we found that CD4 localization is not random in the plasma membrane. Rather, CD4 expressed on the cell surface was concentrated in protruding membrane structures (Fig. 1A). A similar experiment was conducted utilizing live cells expressing the CD4-YFP construct. Three-dimensional reconstruction (which allows rotation of images) revealed that CD4-YFP in living cells accumulated in cellular protrusions similar to those in which unfused CD4 was found in fixed cells (Fig. 1B). This is clear when the boxed region shown in the figure is rotated 45 or 90 degrees (Fig. 1B, left panels). The resulting side view reveals that the projections are sticking out of the cell surface. In some cases, accumulation was also observed at sites of cell-cell contact. Comparably, GFP- and CFP-conjugated CCR5 had a similar localization in the membranes of fixed cells (Fig. 1C and E).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of fluorescent fusion proteins. (A) Selective distribution of CD4 in membrane protrusions in transfected HeLa cells. Cells were fixed and stained for CD4. (B) Left, a similar distribution of CD4-YFP was observed during live cell imaging of transfected HeLa cells. Bright spots toward the center of the cell depict CD4 in intracellular vesicles. The white box indicates the specific area of interest depicted at the right. Right, volume projection depicts 0-, 45-, and 90-degree rotation of the boxed image, demonstrating clear localization of CD4 in cellular protrusions. (C) Fixed cell imaging of 293T cells expressing CCR5-GFP demonstrated localization of CCR5 in similar membrane protrusions. (D) Rapid internalization of CD4-YFP was observed after the addition of 50 ng of PMA per ml to transfected HeLa cells. Cells were imaged before (left) and 20 min after (right) PMA treatment. (E) Ligand-specific internalization was observed in 293T cells expressing CCR5-CFP. Cells were imaged before (left) and 1 h after (right) the addition of 100 nM AOP-RANTES. All cells were imaged using deconvolution microscopy and are shown as volume projections (created with API Softworx software). Bars, 15 μm.

Because endogenously expressed receptor and coreceptor are subject to internalization upon ligand binding, fluorescent fusion constructs were tested for similar activity. Phorbol ester-induced internalization of CD4 has been well documented in the literature (1). Therefore, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma)-induced internalization of the CD4-YFP fusion protein was examined in addition to chemokine-induced internalization of CCR5-CFP in live cells. As shown in Fig. 1D, PMA efficiently induced the internalization of CD4-YFP expressed in HeLa cells. Similarly, the addition of amino-oxypentane (AOP)-RANTES (a generous gift of Oliver Hartley) to CCR5-CFP-expressing 293T cell cultures led to the internalization of the coreceptor molecule (Fig. 1E), demonstrating that both of the fusion proteins were behaving as previously reported for the native versions (3).

The ability of the receptor and coreceptor fusion proteins to function as their native counterparts in HIV entry was confirmed using a β-galactosidase assay for infection. HeLa cells containing the HIV long terminal repeat linked to a β-galactosidase reporter gene were transfected with CD4-YFP or CCR5-CFP. At 2 days posttransfection, the cells were infected with appropriate strains of virus for 2 h. Unbound virus was washed, and cells were cultured for 48 h prior to assay. Cells were then fixed and stained, and infected foci were counted using light microscopy. Substantial infection was detected in cultures expressing both CD4 and CCR5 fluorescent fusion constructs, while no infection was observed in nontransfected control cultures (data not shown). The CCR5-GFP derivative used here has been previously reported to be functional for HIV infection (4).

Thus, both CD4 and CCR5 fluorescent fusion constructs looked and behaved identically to what would be expected for the native proteins, as demonstrated by the pattern of surface expression, response to appropriate ligand stimulation, and functional behavior as receptor and coreceptor. However, we observed that both CD4 and CCR5 accumulated in certain cell surface structures. Therefore, further investigation was conducted to determine the nature of these membrane protrusions.

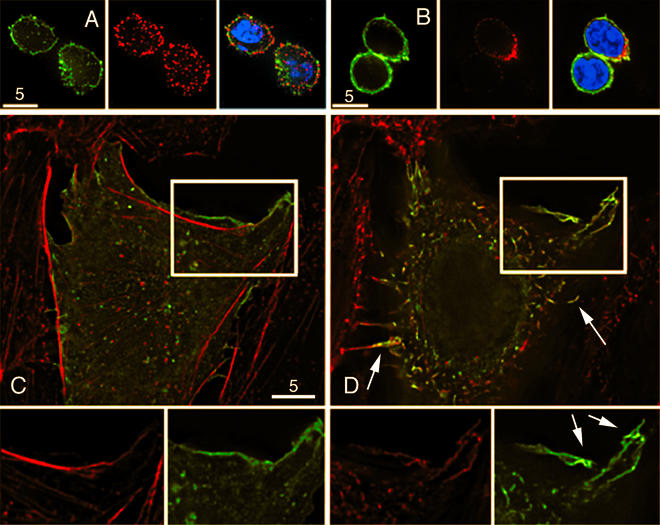

Primary T cells were fixed and stained for actin and CD4 using Oregon Green phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), anti-CD4 from the SIM.4 hybridoma (provided by James Hildreth, NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID]), and a Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Image analysis revealed that much of the CD4 (red) accumulated at sites of actin staining (green) (Fig. 2A). The CD4 that was not associated with actin could be sequestered in intracellular vesicles, which appear to be coincident with the plasma membrane in primary T cells because of their small cytoplasm. Figure 2A shows staining of actin alone, CD4 alone, and CD4 and actin together, with Hoechst staining for cell nuclei. Similar results were observed when phytohemagglutinin-activated T cells were stained for actin (green) and CCR5 (red) (antibodies from R&D Systems were provided by NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, NIAID) (Fig. 2B). Expression of CCR5 was heterogeneous, with many cells expressing little or no CCR5. Because it was somewhat difficult to obtain information regarding the colocalization of proteins due to the small size of the primary cells, additional experiments were conducted using various cell lines in order to gain a clearer perspective of CD4, CCR5, and actin localization. CHO K1 cells growing on glass coverslips were transfected with CD4-YFP, fixed, stained for actin by use of Texas Red phalloidin (Molecular Probes), and imaged in three dimensions using deconvolution microscopy. Analysis of individual image slices taken as part of the z-series revealed that CD4 was not constitutively colocalized with actin. Figure 2C shows a representative image taken toward the bottom of the cell (proximal to the interface between the coverslip and the cell membrane), where CD4 localization (green) is clearly separate from the actin stress fibers (red). A better perspective can be gained when looking closely at actin and CD4 staining individually in the same section of the cell, which is also shown in Fig. 2C (bottom panels).

FIG. 2.

CD4 and CCR5 localize to actin-dependent structures. (A) Colocalization of CD4 and actin was imaged in resting primary T cells that were adhered onto coverslips by use of poly-l-lysine for 5 min, fixed, and stained for actin (left) with phalloidin, CD4 (middle) with anti-CD4 antibody, and cell nuclei (merged image, right) with Hoechst stain. (B) Activated T cells were stained for actin (left), surface CCR5 (middle), or cell nuclei (merged image, right). (C) Representative image from a z-series of CHO K1 cells transfected with CD4-YFP and stained for actin taken proximal to the coverslip, where actin stress fibers predominate. The boxed region indicates the area of interest shown in detail at the bottom. Bottom, individual imaging of actin (left) and CD4 (right) revealed that CD4 is not constitutively associated with cellular actin. (D) An alternative plane from the same z-series taken distal to the coverslip interface shows CD4 and actin colocalization in membrane protrusions. Arrows in the upper panel point to microvilli, while arrows in the lower panel point to ruffles. Bars, 5 μm. A movie showing the z-series, including Fig. 2C and D, is available at http://www.uic.edu/depts/mcmi/hope.

Conversely, when a plane of the cell more distal to the coverslip interface was imaged, CD4 colocalization with actin was readily observed in membrane structures protruding from the cell (Fig. 2D). These protrusions are actin-rich and are likely to be microvilli or membrane ruffles. This finding is consistent with two recent reports utilizing immunogold electron microscopy that found that CD4 is localized in microvilli (10, 20). Both microvilli and membrane ruffles are characterized by the presence of actin as well as the cytoskeletal linker protein ezrin. Ezrin, a member of the ERM (ezrin, radixin, moesin) family of organizational proteins, acts as a dynamic link between the actin cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane and is involved in the formation of microvilli, cell adhesion, motility, trafficking, and cell signaling (5, 15). Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated that ezrin can be incorporated into budding HIV virions in addition to other host cytoskeletal components (17). Therefore, further experiments were carried out to determine if CD4 and CCR5 localized to actin-dependent, ezrin-enriched structures.

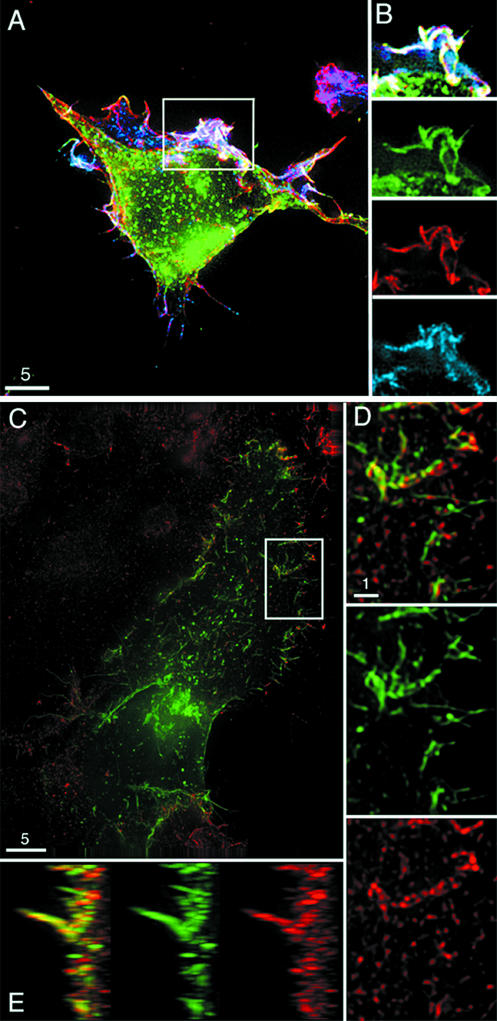

293T cells were transfected with CD4-YFP, and 48 h later they were fixed and stained for actin by use of Texas Red phalloidin (Molecular Probes) and for ezrin by use of a monoclonal antibody against ezrin (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, Colo.) and a Cy5 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). As shown in Fig. 3A, all three proteins accumulated in the same membrane structures in fixed cells. When a closer view is taken of the boxed region shown in Fig. 3A, extensive CD4 (green), actin (red), and ezrin (blue) colocalization can be observed (white). The separated color images of CD4, actin, and ezrin demonstrate the localization of these proteins in a ruffling area of the membrane (Fig. 3B). Similar imaging studies were performed to analyze CCR5-GFP and ezrin expression. Considerable colocalization of CCR5-GFP (green) and ezrin (red) can be observed in apparent microvilli (Fig. 3C and D). Additional individual analysis of CCR5-GFP and ezrin demonstrated enrichment of these proteins in the same membrane protrusions (Fig. 3D). When this image is rotated 90 degrees on its side, obvious colocalization of CCR5 and ezrin is observed in microvilli and other membrane structures (Fig. 3E).

FIG. 3.

CD4 and CCR5 accumulate in ezrin-enriched structures. (A) 293T cells transfected with CD4-YFP were fixed and stained for actin and ezrin. Fixed cell imaging shows CD4 (green), actin (red), and ezrin (blue) colocalization in membrane ruffles and protrusions in the volume projection of a z-series. The white box depicts the area of interest shown in panel B. (B) A single plane of the series from the boxed area of the membrane is shown in greater detail. The single plane is distal to the coverslip and focuses on an area of extensive membrane ruffling. Combined expression (white) in the area of interest is shown as well as expression of each individual protein. (C) 293T cells transfected with CCR5-GFP (green) were fixed, permeabilized, stained for ezrin (red), and shown as a volume projection of a z-series. The white box indicates the area of interest shown in panels D and E. (D) A volume projection of the region proximal to the coverslip included in the area of interest is shown in greater detail, with areas of CCR5 and ezrin colocalization shown in yellow (top), CCR5 shown in green (middle), and ezrin shown in red (bottom). (E) Volume projection of area of interest rotated 90 degrees to demonstrate localization of CCR5 and ezrin in membrane protrusions. Bars, 5 μm. A movie showing the rotation of Fig. 3D is available at http://www.uic.edu/depts/mcmi/hope.

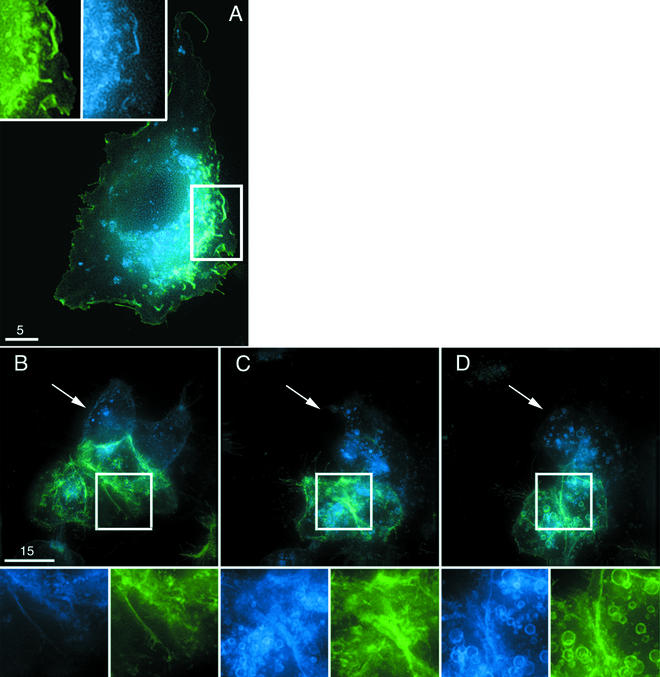

These studies demonstrate that CD4 and CCR5 tend to accumulate in similar environments in the cell membrane. Previous studies describing the colocalization of CD4 and coreceptor have been difficult to interpret due to limitations associated with confocal microscopy and membrane fractionation studies. Using high-resolution deconvolution microscopy, live 293T cells that expressed both CD4-YFP and CCR5-CFP were examined for localization of fluorescent proteins in the cell membrane (Fig. 4A). Strong evidence of colocalization of CD4 (green) and CCR5 (blue) in the same membrane structures, likely microvilli and ruffles, was observed in living cells (Fig. 4A, upper panels). To clarify the nature of the association between CD4 and CCR5 in the cell membrane, ligand-induced internalization studies were conducted using live cells that were cotransfected with CD4-YFP and CCR5-CFP fusion proteins. A single field of cells was imaged over time while ligands to CCR5 and CD4 were added sequentially. Figure 4B shows CD4 (green) and CCR5 (blue) localization in 293T cells prior to the addition of any ligand. Initially, 100 nM AOP-RANTES was added and internalization of CD4 and CCR5 was monitored. After 1 h, PMA was added at 50 ng/ml and cells were monitored for an additional hour. As shown in Fig. 4C, the addition of the AOP-RANTES induced the internalization of CCR5-CFP, as evidenced by the formation of CCR5-CFP-containing vesicles inside of the cell and a loss of CCR5-CFP from the cell membrane. Although some movement of the cells occurred during the initial hour of live cell imaging, the level of CD4-YFP expressed on the cell surface was relatively unchanged (Fig. 4C, bottom). Upon addition of PMA to the cells, rapid and nearly complete internalization of CD4-YFP was observed (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, although CD4-YFP and CCR5-CFP were internalized independently at different times, both proteins localized to the same intracellular vesicles once inside the cell (Fig. 4D). Additional experiments are being conducted in the laboratory to determine the nature of this compartment. Similar results were observed when PMA was initially added to the cells, followed by the addition of AOP-RANTES (data not shown). This finding is consistent with a previous report demonstrating that CCR5 internalization is not induced by phorbol esters (19). Although considerable variation may exist in the expression levels of proteins in individual transfected cells, the relative concentration of these proteins on the cell surface did not impact the individual internalization of CD4-YFP or CCR5-CFP when exposed to ligand stimulation.

FIG. 4.

CD4 and CCR5 colocalize to cellular structures but do not exist as a complex in the cell membrane. (A) Colocalization of receptor and coreceptor molecules was observed in a living 293T cell expressing both CD4-YFP (green) and CCR5-CFP (blue). The white box depicts an area of interest in the membrane with microvilli and ruffles. Expression of each individual protein is shown in greater detail at upper left. (B to D) 293T cells coexpressing CD4-YFP (green) and CCR5-CFP (blue) were imaged before the addition of AOP-RANTES or PMA (B), 1 h after the addition of 100 nM AOP-RANTES (C), and 20 min after the addition of 50 ng of PMA per ml (added after 1 h of incubation with AOP-RANTES) (D). White boxes indicate areas of interest shown in greater detail at the bottom of each panel, demonstrating the individual ligand-specific internalization of each protein. All images in this figure are volume projections. Bars, 15 μm. White arrows, areas in the cell membrane where membrane-associated CCR5-CFP expression (B) or loss of expression (C and D) can be observed after addition of AOP-RANTES.

Internalization studies were used to examine the relationship between CD4 and CCR5 because the behavior of proteins in a complex would be very different from that of individual proteins and should be easily observed after ligand stimulation. For example, if CD4 and CCR5 existed together as a complex in the cell membrane, exposure of the complex to a CD4-specific ligand would induce the internalization of CCR5 in addition to CD4 as a result of the direct association between the two proteins. However, if the proteins were only adjacent to each other or closely apposed in the cell membrane, CD4-specific ligand exposure would not induce the internalization of CCR5. Our experiments demonstrate that CD4 and CCR5 do not exist in a stable complex in the cell membrane. However, the possibility that ligand stimulation may dissociate a pre-existing CD4- and coreceptor-containing complex cannot be excluded.

In summary, the localization of the HIV receptor CD4 and coreceptor CCR5 in the cell membrane is dynamic. However, visualization of fluorescent fusion proteins using high-resolution deconvolution microscopy demonstrated that these proteins tend to accumulate in actin-dependent, ezrin-enriched cellular structures. Additional ligand-specific internalization studies revealed that CD4 and CCR5 are not constitutively associated with one another. Our findings may explain the discrepancies reported in previous studies, as these structures are inherently dynamic and are influenced by variations in cellular activity and culture conditions. For example, the accumulation of CD4 and CCR5 in ezrin-containing structures is consistent with reports that cross-linking with gp120 induces colocalization, often observed in membrane structures (11, 16). Cross-linking of receptor and coreceptor induces signaling (21) which may result in the formation of ezrin-containing structures and hence the observed recruitment. Interestingly, CXCR4 has also been reported to be recruited (11), suggesting that CXCR4 may behave similarly to CCR5 on the cell surface. Thus, the preferential localization of both CD4 and CCR5 in actin-dependent structures and at sites of cell-cell contact may have broad implications for how HIV interacts with receptor and coreceptor to generate a potential site of fusion pore formation. Further investigation is necessary to determine the impact of protein localization and mobility on the ability of target cells expressing both receptor and coreceptor to be infected by HIV.

Acknowledgments

We thank David McDonald, Heather Feltman, and Devon Mann for their contributions to these experiments. We also thank Nathaniel Landau for providing the CCR5-GFP construct and Oliver Hartley for providing AOP-RANTES. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: antibodies to CCR5 from R&D Systems and CD4 hybridoma SIM.4 from James Hildreth.

This work was supported by amfAR fellowship 70572-31-RF to C.M.S. and by NIH grants RO1 AI47770 and R21 AI052051 to T.J.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acres, R. B., P. J. Conlon, D. Y. Mochizuki, and B. Gallis. 1986. Rapid phosphorylation and modulation of the T4 antigen on cloned helper T cells induced by phorbol myristate acetate or antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 261:16210-16214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amara, A., S. L. Gall, O. Schwartz, J. Salamero, M. Montes, P. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, J. L. Virelizier, and F. Arenzana-Seisdedos. 1997. HIV coreceptor downregulation as antiviral principle: SDF-1alpha-dependent internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 contributes to inhibition of HIV replication. J. Exp. Med. 186:139-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt, S. M., R. Mariani, A. U. Holland, T. J. Hope, and N. R. Landau. 2002. Association of chemokine-mediated block to HIV entry with coreceptor internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17291-17299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretscher, A. 1999. Regulation of cortical structure by the ezrin-radixin-moesin protein family. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:109-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choe, H., M. Farzan, Y. Sun, N. Sullivan, B. Rollins, P. D. Ponath, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, G. LaRosa, W. Newman, N. Gerard, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 85:1135-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doms, R. W. 2000. Beyond receptor expression: the influence of receptor conformation, density, and affinity in HIV-1 infection. Virology 276:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foti, M., M. A. Phelouzat, A. Holm, B. J. Rasmusson, and J. L. Carpentier. 2002. p56Lck anchors CD4 to distinct microdomains on microvilli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2008-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyengar, S., J. E. Hildreth, and D. H. Schwartz. 1998. Actin-dependent receptor colocalization required for human immunodeficiency virus entry into host cells. J. Virol. 72:5251-5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhmann, S. E., E. J. Platt, S. L. Kozak, and D. Kabat. 2000. Cooperation of multiple CCR5 coreceptors is required for infections by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 74:7005-7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapham, C. K., M. B. Zaitseva, S. Lee, T. Romanstseva, and H. Golding. 1999. Fusion of monocytes and macrophages with HIV-1 correlates with biochemical properties of CXCR4 and CCR5. Nat. Med. 5:303-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layne, S. P., M. J. Merges, M. Dembo, J. L. Spouge, and P. L. Nara. 1990. HIV requires multiple gp120 molecules for CD4-mediated infection. Nature 346:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louvet-Vallee, S. 2000. ERM proteins: from cellular architecture to cell signaling. Biol. Cell 92:305-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manes, S., G. del Real, R. A. Lacalle, P. Lucas, C. Gomez-Mouton, S. Sanchez-Palomino, R. Delgado, J. Alcami, E. Mira, and A. C. Martinez. 2000. Membrane raft microdomains mediate lateral assemblies required for HIV-1 infection. EMBO Rep. 1:190-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ott, D. E., L. V. Coren, B. P. Kane, L. K. Busch, D. G. Johnson, R. C. Sowder II, E. N. Chertova, L. O. Arthur, and L. E. Henderson. 1996. Cytoskeletal proteins inside human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions. J. Virol. 70:7734-7743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popik, W., T. M. Alce, and W. C. Au. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 uses lipid raft-colocalized CD4 and chemokine receptors for productive entry into CD4+ T cells. J. Virol. 76:4709-4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Signoret, N., M. M. Rosenkilde, P. J. Klasse, T. W. Schwartz, M. H. Malim, J. A. Hoxie, and M. Marsh. 1998. Differential regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 111:2819-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer, I. I., S. Scott, D. W. Kawka, J. Chin, B. L. Daugherty, J. A. DeMartino, J. DiSalvo, S. L. Gould, J. E. Lineberger, L. Malkowitz, M. D. Miller, L. Mitnaul, S. J. Siciliano, M. J. Staruch, H. R. Williams, H. J. Zweerink, and M. S. Springer. 2001. CCR5, CXCR4, and CD4 are clustered and closely apposed on microvilli of human macrophages and T cells. J. Virol. 75:3779-3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissman, D., R. L. Rabin, J. Arthos, A. Rubbert, M. Dybul, R. Swofford, S. Venkatesan, J. M. Farber, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Macrophage-tropic HIV and SIV envelope proteins induce a signal through the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Nature 389:981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao, X., L. Wu, T. S. Stantchev, Y. R. Feng, S. Ugolini, H. Chen, Z. Shen, J. L. Riley, C. C. Broder, Q. J. Sattentau, and D. S. Dimitrov. 1999. Constitutive cell surface association between CD4 and CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7496-7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]