Abstract

The heat-shock response (HSR), a universal cellular response to heat, is crucial for cellular adaptation. In Escherichia coli, the HSR is mediated by the alternative σ factor, σ32. To determine its role, we used genome-wide expression analysis and promoter validation to identify genes directly regulated by σ32 and screened ORF overexpression libraries to identify σ32 inducers. We triple the number of genes validated to be transcribed by σ32 and provide new insights into the cellular role of this response. Our work indicates that the response is propagated as the regulon encodes numerous global transcriptional regulators, reveals that σ70 holoenzyme initiates from 12% of σ32 promoters, which has important implications for global transcriptional wiring, and identifies a new role for the response in protein homeostasis, that of protecting complex proteins. Finally, this study suggests that the response protects the cell membrane and responds to its status: Fully 25% of σ32 regulon members reside in the membrane and alter its functionality; moreover, a disproportionate fraction of overexpressed proteins that induce the response are membrane localized. The intimate connection of the response to the membrane rationalizes why a major regulator of the response resides in that cellular compartment.

Keywords: Heat-shock response, σ32, transcription, microarray

When cells are shifted from low to high temperature, synthesis of the heat-shock proteins (hsps) is rapidly and selectively induced. The heat-shock response (HSR), was first identified by Ritossa (1963), who showed that exposure to heat lead to transient changes in the puffing pattern of salivary chromosomes in Drosophila; Tissieres et al. (1974) demonstrated that these changes reflected the transient induction of several proteins. Initially, hsp function was unclear; however, experiments in several organisms revealed that many hsps were chaperones that promote protein folding (Pelham 1986; Beckmann et al. 1990; Gaitanaris et al. 1990; Skowyra et al. 1990). These studies not only suggested that a major function of the HSR is to maintain the protein folding state of the cell, but also indicated that some of these chaperones, such as Hsp70 and Hsp90, are present in all organisms (Bardwell and Craig 1984, 1987). Thus, both the HSR and some hsps are universally conserved among organisms.

In Escherichia coli, σ32, an alternative σ factor, controls the HSR by directing RNA polymerase to transcribe hsps (Yamamori and Yura 1980; Grossman et al. 1984; Taylor et al. 1984; Cowing et al. 1985). Synthesis of hsps is induced upon temperature upshift and repressed upon temperature downshift (Lemaux et al. 1978; Yamamori et al. 1978; Straus et al. 1987, 1989; Taura et al. 1989), thereby allowing a rapid cellular response to changes in temperature. σ32 is controlled by negative feedback loops controlling its activity (Straus et al. 1989; Blaszczak et al. 1999) and stability (Straus et al. 1987) and a feed forward loop controlling its synthesis (Yuzawa et al. 1993; Morita et al. 1999a, b; El-Samad et al. 2005). σ32 regulon members mediate both feedback loops: The FtsH protease controls σ32 stability (Herman et al. 1995; Tatsuta et al. 1998), and the DnaKJ and GroEL/S chaperone machines control σ32 activity (Gamer et al. 1996; Tatsuta et al. 1998; Guisbert et al. 2004), ensuring homeostatic control.

Given the importance of the heat-shock response for cellular adaptation, it is crucial to identify the genes that are induced so that these cellular processes can be identified and investigated. Several global approaches have been utilized in E. coli to identify genes under σ32 control. Both two-dimensional protein gels (Lemaux et al. 1978) and global transcriptional approaches have identified genes induced after transfer to high temperature (Chuang et al. 1993b; Richmond et al. 1999) or after overexpression of σ32 (Zhao et al. 2005); however, there has been no systematic determination of whether these induced genes are directly expressed from σ32-dependent promoters. The few cases where the functions of σ32-dependent genes were identified indicates the importance of this determination: Hsp33, a widely conserved hsp, is a redox activated chaperone (Jakob et al. 1999), thereby providing the first identification of a chaperone of this type, and FtsJ was shown to be a methyltransferase whose substrate is 23S RNA, revealing an unexpected link between the HSR and RNA (Bugl et al. 2000).

We report the identification of most σ32-dependent genes obtained by combining whole-genome expression analysis of genes induced after σ32 overexpression with start site mapping of these genes and in vitro transcription studies, and also on the types of overproduced proteins that signal induction of σ32. Our analysis has almost tripled the number of genes validated to be expressed from σ32-dependent promoters, and revealed that the HSR response targets multiple processes, protects complex proteins, and targets the membrane as well as the cytoplasm. That the σ32-mediated response is intimately related to membrane functionality rationalizes why the FtsH protease controlling σ32 stability resides in the cytoplasmic membrane.

Results

Identification of genes whose transcription increases following overexpression of σ32

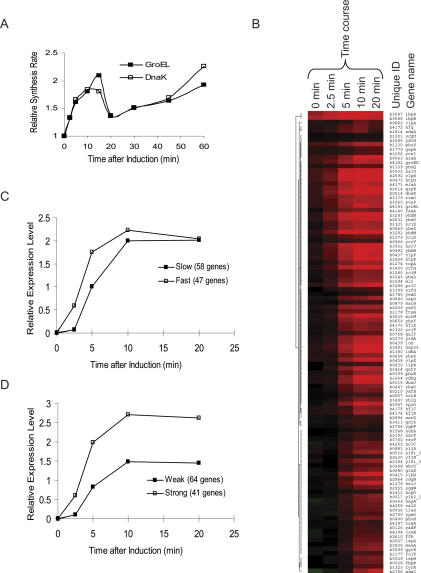

To identify genes regulated by σ32, we compared expression from cells having a plasmid-borne IPTG-inducible rpoH gene with cells carrying the empty vector using whole-genome expression analysis. This approach is preferable to examining cells lacking σ32 because such cells are very sick and grow slowly. Because accumulation of DnaKJ and GroELS damps expression due to feedback inhibition (Gamer et al. 1996; Guisbert et al. 2004), we first determined the kinetics of hsp synthesis following σ32 overexpression. Hsp synthesis peaked at ∼10–15 min following σ32 overexpression (Fig. 1A); thus, we analyzed an expression time course ranging from 0 to 20 min. Relative mRNA levels were determined by parallel two-color hybridization to glass-slide cDNA microarrays. SAM analysis (statistical analysis of microarrays) (Tusher et al. 2001) of gene expression from four independent cultures at 10 min after induction indicated that 105 genes were significantly induced. We used hierarchical clustering to examine the RNA expression pattern of these genes throughout the time course of induction (Fig. 1B) and then determined whether the induced genes consisted of subgroups with distinct induction characteristics using SOM (self-organized maps). We find that induced genes show both temporal distinction (rapid and slower responders) (Fig. 1C) and quantitative differences (strong and weak responders) (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Expression profiles of σ32-regulon members after overexpressing rpoH. (A) Activity of σ32 following overexpression of rpoH. An exponential phase culture of strain CAG50002 (which carries an IPTG-inducible copy of rpoH) growing at 30°C in M9 complete–methionine was induced with IPTG at OD450 = 0.3 (t = 0). At various times, pulse chase analysis was used to determine the rate of synthesis of two σ32-dependent hsps, DnaK, and GroEL. Data is normalized to their synthesis rates at induction (0 min). (B) Hierarchical clustering of 105 genes whose expression is significantly altered following rpoH overexpression (CAG50002) vs. wild type (CAG50001). The color chart illustrates the average expression level at each time point for each gene from three time course experiments. Red denotes increased and green denotes decreased mRNA expression in CAG50002 vs. CAG50001: Maximum intensity represents greater than fourfold change. Time in minutes after induction of rpoH in the time-course experiments is indicated at the top of the figure; genes are identified by their unique ID and name. (C,D) SOM analysis of significantly induced genes following rpoH overexpression. The expression ratios for each gene across three time courses were averaged for each time point. Genes were partitioned based on their induction kinetics (fast/slow; C) or magnitude of induction (strong/weak; D). Each line represents an average trace of expression pattern for that group of genes. Relative Expression Level indicates mean and variance normalized (C) or raw (D) log2 (rpoH overexpressed/wild type) expression ratios.

Identification of induced genes having a σ32 promoter

First, we organized the significantly induced genes into transcription units (TUs) and, where appropriate, expanded the TUs to include other gene members that were less strongly induced based on the criterion that they are adjacent, in the same orientation, induced with similar kinetics, and have an expression pattern typical of an operon (the first gene has the highest induction, followed by decreasing induction of downstream genes). This gave 127 genes organized in 66 potential TUs. We then searched the 300-nucleotide (nt) region upstream of each TU for candidate σ32-promoter sequences using MEME and BioProspector: This predicted 42 promoters upstream of 40/66 TUs (Table 1A,B), of which 14 were previously identified σ32 promoters and 28 were new predictions.

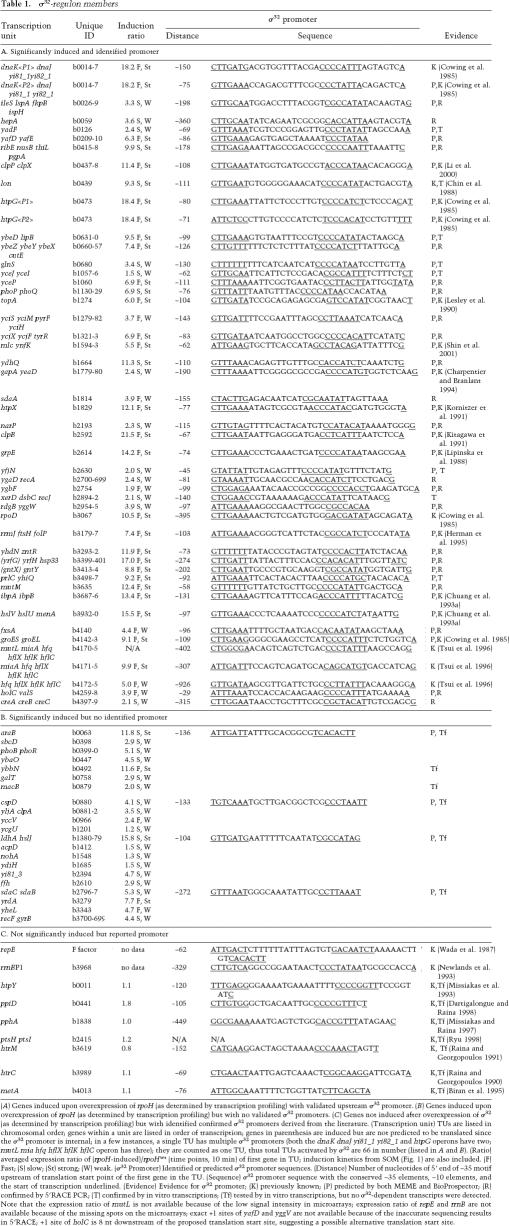

Table 1.

σ32-regulon members

(A) Genes induced upon overexpression of rpoH (as determined by transcription profiling) with validated upstream σ32 promoter. (B) Genes induced upon overexpression of rpoH (as determined by transcription profiling) but with no validated σ32 promoters. (C) Genes not induced after overexpression of σ32 (as determined by transcription profiling) but with identified confirmed σ32 promoters derived from the literature. (Transcription unit) TUs are listed in chromosomal order; genes within a unit are listed in order of transcription; genes in parenthesis are induced but are not predicted to be translated since the σ32 promoter is internal; in a few instances, a single TU has multiple σ32 promoters (both the dnaK dnaJ yi81_1 yi82_1 and htpG operons have two; mutL mia hfq hflX hflK hflC operon has three); they are counted as one TU, thus total TUs activated by σ32 are 66 in number (listed in A and B). (Ratio) averaged expression ratio of (rpoH-induced)/rpoHwt (time points, 10 min) of first gene in TU; induction kinetics from SOM (Fig. 1) are also included. (F) Fast; (S) slow; (St) strong; (W) weak. (σ32 Promoter) Identified or predicted σ32 promoter sequences. (Distance) Number of nucleotides of 5′ end of −35 motif upstream of translation start point of the first gene in the TU. (Sequence) σ32 promoter sequence with the conserved −35 elements, −10 elements, and the start of transcription underlined. (Evidence) Evidence for σ32 promoter; (K) previously known; (P) predicted by both MEME and BioProspector; (R) confirmed by 5′RACE PCR; (T) confirmed by in vitro transcriptions; (Tf) tested by in vitro transcriptions, but no σ32-dependent transcripts were detected. Note that the expression ratio of mutL is not available because of the low signal intensity in microarrays; expression ratio of repE and rrnB are not available because of the missing spots on the microarrays; exact +1 sites of yafD and yggV are not available because of the inaccurate sequencing results in 5′RACE; +1 site of holC is 8 nt downstream of the proposed translation start site, suggesting a possible alternative translation start site.

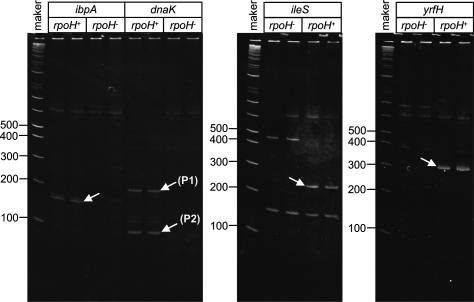

We tested whether the newly predicted promoters and TUs lacking known or predicted promoters had σ32-dependent start sites by using 5′RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) to compare the 5′ ends of mRNAs from cells overexpressing σ32 with those from cells lacking σ32 (Fig. 2). This confirmed 18 out of 28 promoter predictions, using as a criterion a σ32-dependent start site located just downstream of a promoter prediction and identified four new σ32-dependent start sites upstream of the 26 TUs with no predicted promoters (Table 1A). In 11 instances, either no σ32-dependent start site was identified near a prediction or the start site location was inconsistent with that of the prediction. Given that the rrnBP1 has an overlapping σ32 and σ70-dependent promoter (Newlands et al. 1993) and dual recognition promoters would score as σ32 independent in the 5′RACE assay, we retested these 11 promoters in vitro for transcription by both σ32 and σ70 holoenzyme. This identified five dual σ32/σ70-dependent promoters and two additional σ32-dependent promoters (Fig. 3). In toto, we identified 29 new σ32 promoters (Table 1A). We also tested seven previously proposed σ32 promoters located upstream of genes that were not significantly induced on our arrays and detected no σ32-dependent transcripts (Table 1C). Finally, neither 5′RACE nor in vitro transcription identified functional promoters for three of the σ32 promoters proposed by Zhao et al. (2005) (ldhA, macB, and ybbN; Table 1B) based on electrophoretic mobility gel shift by σ32-holoenzyme.

Figure 2.

5′RACE identified 22 σ32-dependent transcription starts. To identify σ32-specific transcripts, mRNA from rpoH+ and rpoH− strains (CAG50002 and CAG50003, respectively) was 5′-labeled with an RNA oligo, reverse-transcribed, amplified by PCR, and then visualized by 7.5% PAGE (see Materials and Methods). Bands present in rpoH+ but not in rpoH− reactions were regarded as σ32 specific. Two known σ32 promoters, dnaK and ibpA, were tested; 22 new σ32-dependent promoters were identified from the 54 newly identified σ32-induced TUs. Displayed are duplicate examples of two new (ibpA, ileS) and two known (dnaK, ibpA) σ32-specific promoters.

Figure 3.

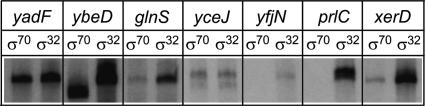

In vitro transcription assays identified seven new promoters transcribed by σ32. Multiround in vitro transcription assays were performed to test 11 predicted and six previously documented promoters. Each promoter template was tested with RNAP containing either σ70 or σ32: σ32-dependent transcripts were obtained from seven promoters, five of which also generated σ70-dependent transcripts (yadF, ybeD, glnS, yceJ, and xerD).

Characteristics of σ32 promoters

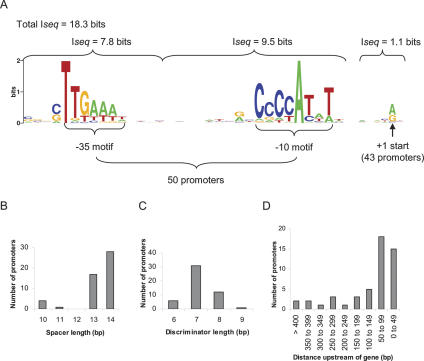

The 29 newly identified σ32 promoters, 20 confirmed promoters, and two previously validated promoters upstream of sequences not present on our arrays (Table 1C) comprise a total of 51 promoters that drive the expression of 49 TUs. The sequence logos of the conserved sequence motifs upstream of the 50 chromosomal σ32 promoters (note repE is on the F factor) together with their information content are displayed in Figure 4A. Virtually all of the total information content of these promoters (18.3 bits) is from the conserved −10 (CCCCATWT) and −35 (TTGAAA) core motifs, with very little contribution from flanking sequences. Figure 4, B and C display histograms of the distance distributions of the promoter elements from each other. Most promoters prefer a 7-nt spacing between –10 and +1 and a 13–14-nt spacing between −10 and −35. However, five promoters contained very short spacers (Fig. 4B). Four of these have very poor −35 sequences, raising the possibility that at these promoters, σ32 makes nonspecific interactions with sequences further upstream at the optimal spacing. Interestingly, four of these promoters contain A/T-rich sequences in the spacer region, suggesting that the intervening DNA may distort upon binding of RNAP. Finally, 66% of all σ32 promoters are located within 100 nt of the downstream gene translation start (Fig. 4D), as is the case for known σ70 promoters (Burden et al. 2005).

Figure 4.

Core promoter motifs of 50 σ32 promoters. Fifty of the 51 validated σ32-dependent promoters were used to derive sequence logos of the core motifs (see Table 1A,B) (the repE promoter was excluded due to the large number of multiple start points that made it difficult to confidently identify the upstream −10 and −35 motifs). The sequences were initially aligned by their start sites and WCONSENSUS was used to search small windows upstream for the conserved −10 and −35 motifs (see Materials and Methods). (A) Sequence logos (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu; Crooks et al. 2004) of the −35, −10, and +1 start site motifs. Note that only 43 promoters were used to derive the start site motif. Seven promoters were excluded that had either multiple starts with no clearly preferred position (b0473 P1 and P2, b1057, b3179, and b3400) or no defined starts (b0209 and b2954). The information content (Iseq) of each conserved sequence window is indicated. (B) Frequency distribution of distance between −35 (TTGAAA) and −10 (CCCATAT) motifs. (C) Frequency distribution of distance between −10 (CCCATAT) motif and +1 (A/G) start. (D) Histogram of the 50 σ32-promoter start sites upstream of the gene translation start.

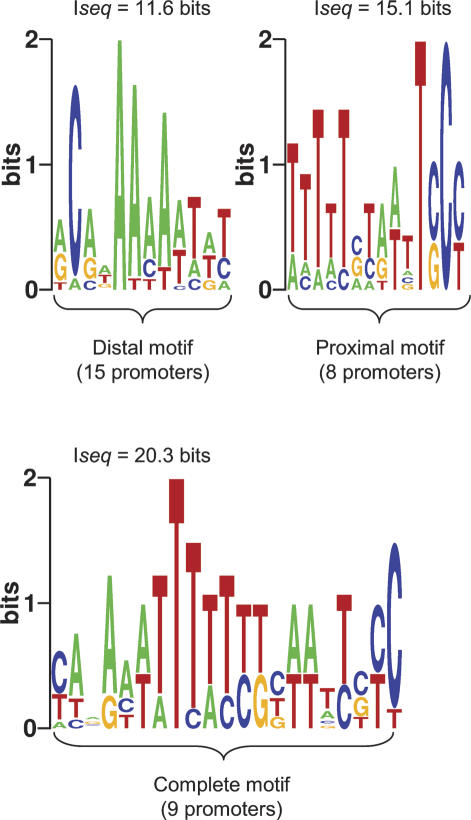

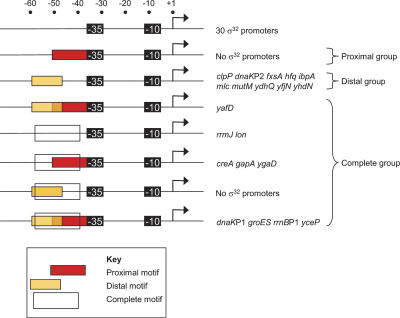

There are several A/T-rich motifs directly upstream of the −35 core motif reminiscent of the A/T-rich UP-elements that bind the α C-terminal domains (αCTDs) of RNAP (Ross et al. 1993; Estrem et al. 1998). We termed these motifs “Complete,” “Proximal,” and “Distal” by analogy to their UP element counterparts (Fig. 5). About 40% of all σ32 promoters contain such motifs, with about half having a distal motif only and the remainder having a complete motif or a combination of complete, distal, and proximal motifs (Fig. 6). We suggest that these A/T-rich σ32-promoter motifs are likely to be αCTD-binding sequences; in fact, the upstream sequences of the rrnB P1 promoter, which contain all three motifs (Fig. 6), has already been shown to stimulate σ32-dependent transcription (Newlands et al. 1993). Interestingly, neither σ32 (Fig. 6) nor σS promoters (Typas and Hengge 2005) have solely proximal sites, although such sites are common in σ70 promoters. This is probably because the σ70 residues that contact αCTD and mediate enhanced transcription from the proximal site are not conserved in σS (Typas and Hengge 2005) and are poorly conserved in σ32 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Sequence logos of A/T-rich motifs upstream of the σ32 promoters. WCONSENSUS was used to search sequences upstream of the −35 element of 50 σ32 promoters (excluding repE). Distal, Proximal, and Complete motifs were identified from the search windows −46 to −60, −36 to −51, and −36 to −60, respectively, by aligning the promoters with respect to their −35 elements and assigning the first “T” of the −35 motif as position −35.

Figure 6.

Location of A/T-rich motifs in σ32 promoters. The location and arrangement of the Distal, Proximal, and Complete A/T-rich motifs identified in Figure 5 are shown for the 50 σ32 promoters.

Functional analysis of the σ32regulon members

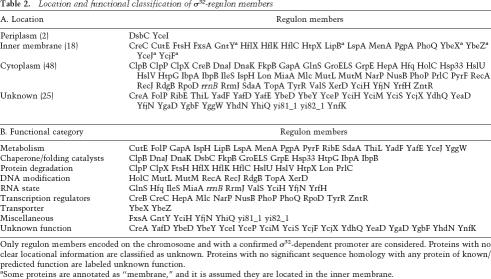

We examined the location and functional classification of validated members of the σ32 regulon (Table 2A,B). A significant fraction (∼25%) of known regulon members reside in the inner membrane, raising the possibility that one role of the response may be to monitor and preserve the membrane during stress. In addition to chaperones and proteases, the regulon is involved in maintaining the integrity of cellular DNA; the connection of the σ32 regulon to the RNA state is more extensive than previously realized; and the regulon is intimately connected to central metabolism and to transport of substrates. Finally, σ32 is a master regulator, altering expression of many transcription factors as well as activity of the transcriptional apparatus itself. Thus, the σ32-mediated hsr has a general role in maintaining cellular homeostasis upon exposure to heat stress.

Table 2.

Location and functional classification of σ32-regulon members

Only regulon members encoded on the chromosome and with a confirmed σ32-dependent promoter are considered. Proteins with no clear locational information are classified as unknown. Proteins with no significant sequence homology with any protein of known/predicted function are labeled unknown function.

aSome proteins are annotated as “membrane,” and it is assumed they are located in the inner membrane.

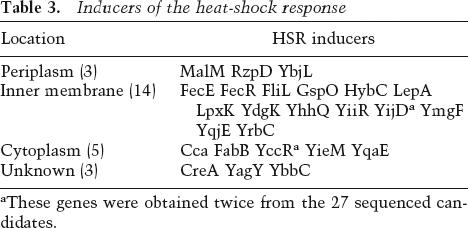

Identification of endogenous proteins that induce the σ32 HSR

A global analysis of proteins that induce a response when overexpressed is a powerful method for determining the signals normally sensed by the response. For example, overexpressed porins induce the σE envelope stress response (Mecsas et al. 1993); later work demonstrated that unassembled porins initiate the signal transduction pathway that induces σE (Walsh et al. 2003). We used the ASKA library, which contains every ORF of E. coli K-12 expressed from an IPTG-inducible promoter on separate plasmids (see Table 4, below) to search for inducers of the σ32 HSR. The plasmids were pooled, introduced into a reporter strain that expresses the lacZ operon from the σ32-dependent htpG promoter, and transformants screened for higher than average σ32 activity by plating on triphenyltetrazolium lactose indicator plates and selecting white colonies (high-lactose fermenters). Candidates were confirmed by restreaking on MacConkey lactose plates (selecting red colonies) and then on Xgal and IPTG (selecting dark blue colonies). Thirty dark-blue colonies were selected at random, the ASKA plasmids extracted and sequenced to determine which ORF was responsible for inducing the HSR (Table 3), and the level of induction of the HSR measured by overexpressing each of the candidates in strains grown in liquid culture (Supplementary Fig. 2). Twenty-five candidates induced the HSR, and surprisingly, ∼60% of these were membrane proteins; this is a significant overrepresentation, given that only 20% of all E. coli proteins are located in the membrane (Serres et al. 2004). Not all overexpressed membrane proteins induced the HSR (e.g., LacY) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

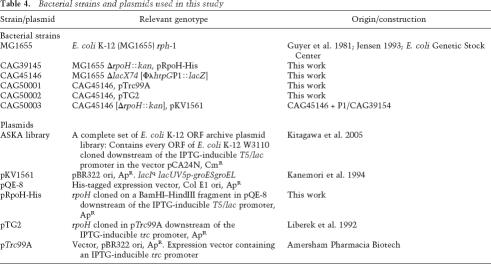

Table 4.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

Table 3.

Inducers of the heat-shock response

aThese genes were obtained twice from the 27 sequenced candidates.

Discussion

The ability of cells to maintain homeostasis in response to temperature stress is essential for viability. In E. coli, σ32-controlled genes govern the immediate response to temperature stress. In this report we used global approaches to provide complete or nearly complete identification of the σ32 regulon and to identify endogenous signals of the response. Our analysis, together with data in the literature, indicates that the multifaceted σ32 stress response not only maintains protein homeostasis but protects DNA and RNA and is further propagated because σ32 controls the expression of other global regulators. Finally, our results reveal an unanticipated connection with the cellular membrane: σ32 senses imbalances in membrane proteins and σ32-controlled genes contribute to membrane homeostasis.

The σ32 regulon

We identified 29 additional σ32 promoters and 57 additional members of the σ32 regulon. At present, the regulon is comprised of 49 TUs regulated by 51 σ32-dependent promoters, which together encode on the chromosome 89 ORFs and one rRNA, and one ORF on the F factor (Table 1). We suggest that our analysis has identified most, if not all, σ32-dependent TUs present on the arrays (∼96% of the genome). This assertion is based on our success in validating previously proposed σ32-dependent TUs. Of the 25 of the previously proposed TUs, 23 were present on our arrays; of these, 16 showed rapid induction after overexpression of σ32. The seven uninduced TUs also failed to generate σ32-dependent transcripts either in vitro or in vivo and contained poorly conserved σ32 promoters (Table 1C). We therefore suggest that these seven promoters either require additional regulators or are not recognized by σ32. Thus, every bona fide previously proposed σ32 TUs present on our array was validated in this analysis.

The consensus promoter sequence derived from the 50 validated σ32 promoters indicates the following highly conserved bases: STTGAAA-N11–12-GNCCCCATWT (Fig. 4; note the optimal spacer length [13–14 bp] is from the core-10 motif, CCCCATWT). The importance of these conserved bases is indicated by their close correspondence to the “functional” σ32-promoter sequence, CTTGA-14 bp-GNCCCCATNT, derived by mutating each position of the core groE σ32-promoter sequence to every other nucleotide (Wang and deHaseth 2003). There are subtle differences in the less-preferred bases between our aligned promoter profile and the derived “functional” σ32-promoter sequence, suggesting that the importance of individual bases may vary according to the context of the local sequence.

We identified five overlapping σ32/σ70 promoters in addition to the previously reported rrnBP1 σ32/σ70 dual promoter (Newlands et al. 1993). Given the similarity between the σ32 and σ70 core promoter sequences (σ70 TTGACA-N17-TATAAT; σ32 TTGAAA-N14-CCCCAT WT) it is likely that both holoenzymes are recognizing the same core promoter sequences. However, as 22 of our σ32 promoters generated only σ32-specific transcripts as detected by 5′RACE, it is unlikely that σ70 holoenzyme directly transcribes many more σ32 promoters, (Table 1A; Fig. 2). However, in Pseudomonas putida, both σS and σ32 holoenzymes recognize the Pm promoter (Dominguez-Cuevas et al. 2005), raising the possibility for promoter overlap between σS and σ32 in E. coli.

Many significantly induced genes did not have a detectable σ32 promoter. Interestingly, of the 47 rapidly induced genes (Fig. 1C), 43 were under σ32 control whether or not they were strongly induced, whereas most induced genes without an identified σ32 promoter (18/25) were only slowly and weakly induced (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 3). Since σ32 controls a number of transcriptional regulators (see below), these transcription factors may be responsible for delayed expression of genes lacking a σ32 promoter. These data suggest that even in bacteria where events are very rapid, careful temporal analysis may be able to resolve cascades of induction.

σ32-mediated temperature adaptation has many cellular targets

A primary role of the σ32 regulon in protein homeostasis was suggested by the fact that >50% of previously known regulon members were either chaperones or proteases (Table 1A). Our results suggest that the regulon also contributes to protein homeostasis by maintaining an adequate supply of complex proteins that contain cofactors, Fe++-S centers, or lipoyl modification. Since the extent to which damaged complex proteins can be repaired is not well known, thermolabile proteins of this type may need to be synthesized at higher rates during temperature stress. The regulon encodes two Fe++-S center proteins (SdaA, IspH), a predicted Fe++-S center protein (YggW), and an IscA homolog (GntY) (Giel et al. 2006) likely to be involved in Fe++-S cluster biogenesis. The regulon also encodes lipoyl protein ligase (LipB) and enzymes participating in the biosynthesis of the cofactors riboflavin (RibE), thiamin (ThiL), folate (FolP), and probably biotin (YafE). If cofactor supply is tightly coupled to demand, these pathways may need to be induced during temperature stress. The particular enzymes in the regulon are likely to be rate-limiting and highly regulated, either because they are at the junction of two pathways (RibE and FolP) or because they utilize ATP (ThiL). Thus, altering the amount of these enzymes is likely to influence the amount of cofactor available to the cell.

σ32-regulon members protect both DNA and RNA (Table 2B). Maintaining genomic integrity is essential for survival of the organism and high temperatures may increase both misincorporation and chromosome damage. The regulon encodes enzymes that mediate mismatch and excision repair (MutL, MutM), general recombination functions that resolve double-strand breaks (RecA, RecJ), and a site-specific recombination system to resolve chromosome dimers (XerD). This response also covalently modifies both classes of stable RNAs, possibly improving their thermal resistance. σ32-regulon members have previously been shown to methylate 23S RNA (FtsJ) (Bugl et al. 2000) and to modify tRNA by transferring Δ3-isopentyl-PP to A37 of tRNA (MiaA; just adjacent to and 3′ of the anticodon) (Tsui et al. 1996). A new regulon member, IspH, also produces Δ3-isopentyl-PP; this tRNA modification stabilizes codon–anticodon pairing (Bjork and Hagervall 2005) and cells lacking this modification are temperature sensitive (Tsui et al. 1996). Finally, the regulon encodes the RNA chaperone Hfq (Table 2B) (Chuang and Blattner 1993; Tsui et al. 1996), which is required for the proper function of small RNAs.

Several regulon functions may promote transcription and translation at high temperatures. Two newly discovered regulon members, HepA and NusB, join TopA (Qi et al. 1996) as general effectors of transcription, and all three may respond to altered supercoiling at high temperature. Previous work indicated that thermal induction of TopA, an RNA polymerase-associated topoisomerase (Cheng et al. 2003) is necessary for normal transcription patterns at high temperature and for thermal resistance (Qi et al. 1996). HepA (RapA) is also an RNA polymerase-associated protein (Sukhodolets et al. 2001) specifically required for RNA polymerase recycling of tightly compacted negatively supercoiled DNA. Induction of NusB, essential for antitermination of rRNA transcription (Zellars and Squires 1999; Torres et al. 2004) may reflect altered requirements for rRNA antitermination when DNA supercoiling is altered, possibly to decrease R-loop formation (Drolet 2006). Finally, a general connection of the regulon to translation was previously established by Korber et al. (2000), who showed that regulon member Hsp15 (YfrH) binds free 50S ribosomal subunits with nascent chains and may promote ribosome recycling. This state is more prevalent at high temperatures (Korber et al. 2000), possibly because translation often terminates prematurely at lethal temperatures (VanBogelen and Neidhardt 1990).

σ32 is also a master regulator controlling expression of seven transcriptional factors (including RpoD) (Table 2B) in addition to functions that alter RNA polymerase action (described above). The proportion of the σ32 regulon devoted to transcriptional factors (∼8%) is similar to that for σS, previously thought to be the only alternative E. coli σ with a propagated response (Weber et al. 2005). The transcriptional regulators under σ32 control mostly sense extracellular conditions: Mlc senses glucose, Pho P/Q senses low Mg++ and is induced in acid stress, ZntR responds to excess Zn++, and NarP induction requires nitrite/nitrate under anaerobic conditions. Intriguingly, many of the genes controlled by these regulators are membrane-localized transporters and other membrane proteins, pointing to the connection of this response to the status of the cytoplasmic membrane.

A comparison of genes directly regulated by HSF (heat-shock factor; controlling the eukaryotic counterpart response) with the σ32-mediated heat-shock response indicates that only chaperones are encoded by both regulons (Hahn et al. 2004; Yamamoto et al. 2005). However, both regulons are of similar size and there is definite overlap in functional classes induced; for example, proteolysis, small molecule transport, additional transcription factors, proteins that modify RNA polymerase, and DNA related proteins. A broad response to heat stress appears to be universal among organisms.

The cytoplasmic membrane is a target of the σ32-mediated hsr

The cytoplasmic membrane maintains cellular integrity and coordinates processes that traverse cellular compartments including secretion and processing of envelope proteins, energy generation, sensing the extracytoplasmic environment, and synthesis and/or transfer of the building blocks for phospholipids, LPS, and peptidoglycan. Previously identified σ32 regulon members FtsH (Herman et al. 1995), HflX, HflC (Chuang and Blattner 1993; Tsui et al. 1996), and HtpX (Kornitzer et al. 1991) play a vital role in membrane quality control; FtsH, together with its regulators HflX and HflC, degrades and dislocates unassembled membrane proteins, and the function of HtpX overlaps with that of FtsH. Our new data indicates that σ32-regulon members have important additional roles in membrane homeostasis (Table 2):

Increasing the potential to make fatty acids by up-regulating expression of carbonic anhydrase (YadF), which converts C02 to bicarbonate (Merlin et al. 2003). The first committed step of fatty acid biosynthesis is a major consumer of bicarbonate (Merlin et al. 2003).

Altering transport properties of the membrane by up-regulating several transporters (Table 2B).

Maintaining the potential for disulfide bond formation and isomerization by increasing menaquinone production (MenA), which is necessary to reoxidize DsbB under anaerobic conditions (Bader et al. 1999) and by up-regulating the disufide bond isomerase DsbC.

Maintaining lipoprotein maturation by up-regulating both signal peptidase II (IspA), which cleaves the proprotein, and CutE, the enzyme that activates lipoproteins by adding palmitate to their N-terminal cysteine (Wu 1996). Because there are >100 lipoproteins, the precise physiological role of this regulation is unclear.

Altering the composition of the lipid bilayer by up-regulating PgpA, an enzyme involved in synthesis of cardiolipin, a minority phospholipid in the inner membrane whose abundance increases during stationary phase (Hiraoka et al. 1993). As cells induce a variety of substances during stationary phase to prevent cell lysis, cardiolipin may impart additional stability to the lipid bilayer.

Altering sensing capacity of the membrane by inducing the expression of two membrane-localized histidine kinases (CreC and PhoQ) and their cytoplasmic response regulators.

These results strongly implicate σ32-regulon members in maintaining membrane functionality and homeostasis. This connection rationalizes why the σE-envelope stress response regulates σ32 in all organisms examined thus far, making this one of the most conserved features of the response (Rhodius et al. 2006). Because the inner membrane controls the flow of building blocks and proteins to the envelope, induction of σ32 is essential to maintaining envelope homeostasis.

It is provocative that genome-wide analysis indicated that when overproduced, very few cytoplasmic proteins and a disproportionate number of membrane proteins induce the σ32 response. Whether this simply reflects an increased propensity for accumulated membrane proteins to misfold or whether a novel mechanism is involved, the fact that σ32 is particularly sensitive to imbalances in membrane proteins provides a rationale for utilizing FtsH to degrade σ32. Because FtsH carries out both membrane quality control and degradation of σ32, these two processes can be coordinated, thereby providing the cell with a means to assess membrane homeostasis. Interestingly, the overexpressed membrane proteins that induce the σ32-mediated response also induce the response mediated by the two-component CpxRA system (C. Herman, unpubl.). Moreover, at least two proteins, HtpX and DsbC, are jointly induced by both CpxRA and σ32. Additional evidence that CpxRA senses membrane status has recently been presented by Ito (Shimohata et al. 2002). Thus, σ32 and CpxRA may jointly protect the cell membrane during times of stress.

Materials and methods

Medium, strains, and plasmids

M9 medium (Sambrook et al. 1989) was supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, vitamins, all amino acids (40 μg/mL), ampicillin (100 μg/mL), and/or kanamycin (30 μg/mL) as required and is referred to as M9 complete. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 4.

Pulse chase

A 750-μL aliquot of cells was removed from a culture growing exponentially in M9 complete–methionine at 30°C, labeled for 1 min with 80 μC [35S]methionine, chased for 1 min with excess unlabeled methionine, precipitated with 100 μL of ice-cold 50% TCA (15 min on ice), centrifuged, and resuspended in 50 μL of 2% SDS and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Equal counts were loaded in each lane of a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel and bands corresponding to GroEL and DnaK proteins were quantified using the program ImageQuant version 1.2.

Time course microarray experiments

Cells were inoculated to OD450 = 0.02 from fresh overnight cultures of CAG50002 (Table 4; vector has IPTG-inducible rpoH) or CAG50001 (Table 4; control vector) into 100 mL of M9 complete in 500-mL conical flasks and grown aerobically at 30°C in a gyratory water bath (model G76 from New Brunswick Scientific) shaking at 240 rpm. At OD450 = 0.3, cultures were induced with IPTG (1 mM final concentration). Ten-milliliter samples for microarray analysis were removed immediately prior to and at 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 min after induction, added to ice-cold 5% water–saturated phenol in ethanol, and centrifuged at 6600g. Cell pellets were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Preparation of labeled probes and microarray procedures were performed exactly as described in Rhodius et al. (2006) and Supplemental Material. Raw and normalized microarray expression data are available on the NCBI Gene Expression Onmibus (GEO) Web site (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/geo) under the accession code GSE4321.

Additional Materials and Methods are provided in Supplemental Material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chi Zen Lu for supplying purified RNAP core, σ32, and σ70 proteins, H. Mori from the Japanese E. coli consortium for the generous gift of the ASKA plasmid ORF library, and P. Kiley for advice about FeS proteins and assembly of complex proteins. This work was supported by Ajinomoto Co., Inc., and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants GM57755 and GM36278 (to C.A.G.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1428206

References

- Bader M., Muse W., Ballou D.P., Gassner C., Bardwell J.C. Oxidative protein folding is driven by the electron transport system. Cell. 1999;98:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J.C., Craig E.A. Major heat shock gene of Drosophila and the Escherichia coli heat-inducible dnaK gene are homologous. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984;81:848–852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J.C., Craig E.A. Eukaryotic Mr 83,000 heat shock protein has a homologue in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:5177–5181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann R.P., Mizzen L.E., Welch W.J. Interaction of Hsp 70 with newly synthesized proteins: Implications for protein folding and assembly. Science. 1990;248:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.2188360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran D., Brot N., Weissbach H., Ron E.Z. Heat shock-dependent transcriptional activation of the metA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1374–1379. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1374-1379.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork G., Hagervall T. Transfer RNA Modification. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology. In: Curtis R. III, editor. Module 4.6.2. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczak A., Georgopoulos C., Liberek K. On the mechanism of FtsH-dependent degradation of the σ 32 transcriptional regulator of Escherichia coli and the role of the Dnak chaperone machine. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:157–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugl H., Fauman E.B., Staker B.L., Zheng F., Kushner S.R., Saper M.A., Bardwell J.C., Jakob U. RNA methylation under heat shock control. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burden S., Lin Y.X., Zhang R. Improving promoter prediction for the NNPP2.2 algorithm: A case study using Escherichia coli DNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:601–607. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier B., Branlant C. The Escherichia coli gapA gene is transcribed by the vegetative RNA polymerase holoenzyme E σ 70 and by the heat shock RNA polymerase E σ 32. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:830–839. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.830-839.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B., Zhu C.X., Ji C., Ahumada A., Tse-Dinh Y.C. Direct interaction between Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and the zinc ribbon domains of DNA topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30705–30710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin D.T., Goff S.A., Webster T., Smith T., Goldberg A.L. Sequence of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. A heat-shock gene which encodes the ATP-dependent protease La. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:11718–11728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S.E., Blattner F.R. Characterization of twenty-six new heat shock genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:5242–5252. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5242-5252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S.E., Burland V., Plunkett G., III, Daniels D.L., Blattner F.R. Sequence analysis of four new heat-shock genes constituting the hslTS/ibpAB and hslVU operons in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1993a;134:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S.E., Daniels D.L., Blattner F.R. Global regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993b;175:2026–2036. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.2026-2036.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowing D.W., Bardwell J.C., Craig E.A., Woolford C., Hendrix R.W., Gross C.A. Consensus sequence for Escherichia coli heat shock gene promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1985;82:2679–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartigalongue C., Raina S. A new heat-shock gene, ppiD, encodes a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase required for folding of outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1998;17:3968–3980. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Cuevas P., Marin P., Ramos J.L., Marques S. RNA polymerase holoenzymes can share a single transcription start site for the Pm promoter. Critical nucleotides in the −7 to −18 region are needed to select between RNA polymerase with σ38 or σ32. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41315–41323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M. Growth inhibition mediated by excess negative supercoiling: The interplay between transcription elongation, R-loop formation and DNA topology. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:723–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Samad H., Kurata H., Doyle J.C., Gross C.A., Khammash M. Surviving heat shock: Control strategies for robustness and performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:2736–2741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrem S.T., Gaal T., Ross W., Gourse R.L. Identification of an UP element consensus sequence for bacterial promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:9761–9766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitanaris G.A., Papavassiliou A.G., Rubock P., Silverstein S.J., Gottesman M.E. Renaturation of denatured λ repressor requires heat shock proteins. Cell. 1990;61:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer J., Multhaup G., Tomoyasu T., McCarty J.S., Rudiger S., Schonfeld H.J., Schirra C., Bujard H., Bukau B. A cycle of binding and release of the DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE chaperones regulates activity of the Escherichia coli heat shock transcription factor σ32. EMBO J. 1996;15:607–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giel J., Rodionov D., Liu M., Blattner F.R., Kiley P.J. IscR-dependent gene expression links iron–sulfur assembly to the control of O2-regulated genes in Escehrichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;60:1058–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A.D., Erickson J.W., Gross C.A. The htpR gene product of E. coli is a σ factor for heat-shock promoters. Cell. 1984;38:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbert E., Herman C., Lu C.Z., Gross C.A. A chaperone network controls the heat shock response in E. coli. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:2812–2821. doi: 10.1101/gad.1219204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer M.S., Reed R.R., Steitz J.A., Low K.B. Identification of a sex-factor-affinity site in E. coli as γ δ. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1981;45:135–140. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J.S., Hu Z., Thiele D.J., Iyer V.R. Genome-wide analysis of the biology of stress responses through heat shock transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5249–5256. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5249-5256.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman C., Thevenet D., D’Ari R., Bouloc P. Degradation of σ 32, the heat shock regulator in Escherichia coli, is governed by HflB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka S., Matsuzaki H., Shibuya I. Active increase in cardiolipin synthesis in the stationary growth phase and its physiological significance in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U., Muse W., Eser M., Bardwell J.C. Chaperone activity with a redox switch. Cell. 1999;96:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80547-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K.F. The Escherichia coli K-12 ‘wild types’ W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frameshift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3401–3407. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3401-3407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemori M., Mori H., Yura T. Effects of reduced levels of GroE chaperones on protein metabolism: Enhanced synthesis of heat shock proteins during steady-state growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4235–4242. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4235-4242.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M., Wada C., Yoshioka S., Yura T. Expression of ClpB, an analog of the ATP-dependent protease regulatory subunit in Escherichia coli, is controlled by a heat shock σ factor (σ 32). J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:4247–4253. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4247-4253.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M., Ara T., Arifuzzaman M., Ioka-Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., Toyonaga H., Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (A complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): Unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber P., Stahl J.M., Nierhaus K.H., Bardwell J.C. Hsp15: A ribosome-associated heat shock protein. EMBO J. 2000;19:741–748. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornitzer D., Teff D., Altuvia S., Oppenheim A.B. Isolation, characterization, and sequence of an Escherichia coli heat shock gene, htpX. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:2944–2953. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2944-2953.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaux P.G., Herendeen S.L., Bloch P.L., Neidhardt F.C. Transient rates of synthesis of individual polypeptides in E. coli following temperature shifts. Cell. 1978;13:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley S.A., Jovanovich S.B., Tse-Dinh Y.C., Burgess R.R. Identification of a heat shock promoter in the topA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:6871–6874. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6871-6874.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Tao Y.P., Simon L.D. Expression of different-size transcripts from the clpP-clpX operon of Escherichia coli during carbon deprivation. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6630–6637. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6630-6637.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberek K., Galitski T.P., Zylicz M., Georgopoulos C. The DnaK chaperone modulates the heat shock response of Escherichia coli by binding to the σ32 transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinska B., King J., Ang D., Georgopoulos C. Sequence analysis and transcriptional regulation of the Escherichia coli grpE gene, encoding a heat shock protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7545–7562. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecsas J., Rouviere P.E., Erickson J.W., Donohue T.J., Gross C.A. The activity of σ E, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible σ-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:2618–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin C., Masters M., McAteer S., Coulson A. Why is carbonic anhydrase essential to Escherichia coli? J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6415–6424. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6415-6424.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Raina S. Signal transduction pathways in response to protein misfolding in the extracytoplasmic compartments of E. coli: Role of two new phosphoprotein phosphatases PrpA and PrpB. EMBO J. 1997;16:1670–1685. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Georgopoulos C., Raina S. The Escherichia coli heat shock gene htpY: Mutational analysis, cloning, sequencing, and transcriptional regulation. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:2613–2624. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2613-2624.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M., Kanemori M., Yanagi H., Yura T. Heat-induced synthesis of σ32 in Escherichia coli: Structural and functional dissection of rpoH mRNA secondary structure. J. Bacteriol. 1999a;181:401–410. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.401-410.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M.T., Tanaka Y., Kodama T.S., Kyogoku Y., Yanagi H., Yura T. Translational induction of heat shock transcription factor σ32: Evidence for a built-in RNA thermosensor. Genes & Dev. 1999b;13:655–665. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlands J.T., Gaal T., Mecsas J., Gourse R.L. Transcription of the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter by the heat shock RNA polymerase (E σ 32) in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:661–668. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.661-668.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H.R. Speculations on the functions of the major heat shock and glucose-regulated proteins. Cell. 1986;46:959–961. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Menzel R., Tse-Dinh Y.C. Effect of the deletion of the σ 32-dependent promoter (P1) of the Escherichia coli topoisomerase I gene on thermotolerance. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;21:703–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.241390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S., Georgopoulos C. A new Escherichia coli heat shock gene, htrC, whose product is essential for viability only at high temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:3417–3426. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3417-3426.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S., Georgopoulos C. The htrM gene, whose product is essential for Escherichia coli viability only at elevated temperatures, is identical to the rfaD gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3811–3819. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius V.A., Suh W.C., Nonaka G., West J., Gross C.A. Conserved and variable functions of the σE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond C.S., Glasner J.D., Mau R., Jin H., Blattner F.R. Genome-wide expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3821–3835. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa F. New puffs induced by temperature shock, DNP and salicylate in salivary chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 1963;37:122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ross W., Gosink K.K., Salomon J., Igarashi K., Zou C., Ishihama A., Severinov K., Gourse R.L. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science. 1993;262:1407–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.8248780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S. CRP.cAMP-dependent transcription activation of the Escherichia colipts Po promoter by the heat shock RNA polymerase (Eσ32) in vitro. Mol. Cells. 1998;8:614–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York.: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Serres M.H., Goswami S., Riley M. GenProtEC: An updated and improved analysis of functions of Escherichia coli K-12 proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D300–D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohata N., Chiba S., Saikawa N., Ito K., Akiyama Y. The Cpx stress response system of Escherichia coli senses plasma membrane proteins and controls HtpX, a membrane protease with a cytosolic active site. Genes Cells. 2002;7:653–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D., Lim S., Seok Y.J., Ryu S. Heat shock RNA polymerase (E σ(32)) is involved in the transcription of mlc and crucial for induction of the Mlc regulon by glucose in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25871–25875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D., Georgopoulos C., Zylicz M. The E. coli dnaK gene product, the hsp70 homolog, can reactivate heat-inactivated RNA polymerase in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. Cell. 1990;62:939–944. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90268-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus D.B., Walter W.A., Gross C.A. The heat shock response of E. coli is regulated by changes in the concentration of σ 32. Nature. 1987;329:348–351. doi: 10.1038/329348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus D.B., Walter W.A., Gross C.A. The activity of σ 32 is reduced under conditions of excess heat shock protein production in Escherichia coli. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:2003–2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolets M.V., Cabrera J.E., Zhi H., Jin D.J. RapA, a bacterial homolog of SWI2/SNF2, stimulates RNA polymerase recycling in transcription. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:3330–3341. doi: 10.1101/gad.936701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta T., Tomoyasu T., Bukau B., Kitagawa M., Mori H., Karata K., Ogura T. Heat shock regulation in the ftsH null mutant of Escherichia coli: Dissection of stability and activity control mechanisms of σ32 in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;30:583–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taura T., Kusukawa N., Yura T., Ito K. Transient shut off of Escherichia coli heat shock protein synthesis upon temperature shift down. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;163:438–443. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W.E., Straus D.B., Grossman A.D., Burton Z.F., Gross C.A., Burgess R.R. Transcription from a heat-inducible promoter causes heat shock regulation of the σ subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell. 1984;38:371–381. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90492-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissieres A., Mitchell H.K., Tracy U.M. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: Relation to chromosome puffs. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;84:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M., Balada J.M., Zellars M., Squires C., Squires C.L. In vivo effect of NusB and NusG on rRNA transcription antitermination. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:1304–1310. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1304-1310.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui H.C., Feng G., Winkler M.E. Transcription of the mutL repair, miaA tRNA modification, hfq pleiotropic regulator, and hflA region protease genes of Escherichia coli K-12 from clustered Eσ32-specific promoters during heat shock. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5719–5731. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5719-5731.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher V.G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typas A., Hengge R. Differential ability of σ(s) and σ70 of Escherichia coli to utilize promoters containing half or full UP-element sites. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen R.A., Neidhardt F.C. Ribosomes as sensors of heat and cold shock in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990;87:5589–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada C., Imai M., Yura T. Host control of plasmid replication: Requirement for the σ factor σ 32 in transcription of mini-F replication initiator gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:8849–8853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh N.P., Alba B.M., Bose B., Gross C.A., Sauer R.T. OMP peptide signals initiate the envelope-stress response by activating DegS protease via relief of inhibition mediated by its PDZ domain. Cell. 2003;113:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., deHaseth P.L. σ 32-Dependent promoter activity in vivo: Sequence determinants of the groE promoter. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5800–5806. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5800-5806.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H., Polen T., Heuveling J., Wendisch V.F., Hengge R. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: σS-dependent genes, promoters, and σ factor selectivity. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:1591–1603. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Biosynthesis of lipoproteins. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology. In: Neidhardt F.C., et al., editors. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 1996. pp. 1005–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori T., Yura T. Temperature-induced synthesis of specific proteins in Escherichia coli: Evidence for transcriptional control. J. Bacteriol. 1980;142:843–851. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.843-851.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori T., Ito K., Nakamura Y., Yura T. Transient regulation of protein synthesis in Escherichia coli upon shift-up of growth temperature. J. Bacteriol. 1978;134:1133–1140. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1133-1140.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A., Mizukami Y., Sakurai H. Identification of a novel class of target genes and a novel type of binding sequence of heat shock transcription factor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11911–11919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa H., Nagai H., Mori H., Yura T. Heat induction of σ 32 synthesis mediated by mRNA secondary structure: A primary step of the heat shock response in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5449–5455. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.23.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellars M., Squires C.L. Antiterminator-dependent modulation of transcription elongation rates by NusB and NusG. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:1296–1304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Liu M., Burgess R.R. The global transcriptional response of Escherichia coli to induced σ 32 protein involves σ 32 regulon activation followed by inactivation and degradation of σ 32 in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:17758–17768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]