Abstract

We studied 247 Japanese males with congenital deutan color-vision deficiency and found that 37 subjects (15.0%) had a normal genotype of a single red gene followed by a green gene(s). Two of them had missense mutations in the green gene(s), but the other 35 subjects had no mutations in either the exons or their flanking introns. However, 32 of the 35 subjects, including all 8 subjects with pigment-color defect, a special category of deuteranomaly, had a nucleotide substitution, A−71C, in the promoter of a green gene at the second position in the red/green visual-pigment gene array. Although the −71C substitution was also present in color-normal Japanese males at a frequency of 24.3%, it was never at the second position but always found further downstream. The substitution was found in 19.4% of Chinese males and 7.7% of Thai males but rarely in Caucasians or African Americans. These results suggest that the A−71C substitution in the green gene at the second position is closely associated with deutan color-vision deficiency. In Japanese and presumably other Asian populations further downstream genes with −71C comprise a reservoir of the visual-pigment genes that cause deutan color-vision deficiency by unequal crossing over between the intergenic regions.

The red/green visual-pigment genes, which are present in a head-to-tail tandem manner on the long arm of human chromosome X, have been analyzed both in color-normal and color-deficient males (1–9). Color-normal males always have an array of a red gene at the first position and one or more green genes downstream (3, 4). In individuals with more than two pigment genes, only the two upstream genes are thought to be expressed (5, 8), although expression of the additional downstream genes has been reported (10, 11). In color-deficient European males, protan deficiencies are associated with the presence of a 5′ red–green hybrid gene (2, 8, 9, 12), and deutan deficiencies are associated with either a green-gene deletion (2, 12) or the presence of a 5′ green–red hybrid gene (2, 8, 9, 12). However, in other populations such phenotype–genotype relationships have not been established. For example, in African males, congenital color-vision deficiencies are less frequent (1–3%) than in Europeans (8–10%), but the frequency of a 5′ green–red hybrid gene is high (15%) (13). Therefore, it was necessary to examine whether the phenotype–genotype relationships that occur in European males are applicable to other populations.

In this study we investigated the red/green visual-pigment genes in a Japanese population that consisted of 230 color-normal and 341 color-deficient males. Of the 341 color-deficient subjects, 42 (5 protan and 37 deutan, 12.3%) had a normal genotype of a red gene followed by a green gene(s). Of the 37 deutan subjects, 32 (86.5%) had a nucleotide substitution, A−71C, in the promoter of a green gene(s) but no mutations in the exons or their flanking introns. Color-normal Japanese males as well as populations of Chinese, Thailanders, Caucasians, and African Americans were also tested for the substitution. We report here a close association of the A−71C substitution with deutan color-vision deficiency.

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes of 230 Japanese males whose normal color-vision status was assessed with Ishihara pseudoisochromatic plates. Genomic DNA was also isolated from 247 Japanese males with deutan congenital color-vision deficiencies who had consulted Shiga University of Medical Science Hospital or Japan Red Cross Nagoya First Hospital. Their color-vision status was usually assessed with a Nagel anomaloscope (model I, Schmidt & Haensch, Berlin). Definition of the “pigment-color defect” in this study is deuteranomaly showing a narrow matching range within 30–50 but not excluding a value of 40 at the anomaloscopic examination. Genomic DNA was also obtained from 98 color-normal Chinese males, 104 color-normal male Thailanders, and 9 color-normal Caucasian males. They all were informed of the aims and methods of this work and gave their consent. All procedures were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genomic DNA from 41 Caucasian males and 50 African Americans (14 males and 36 females) whose color-vision status was unknown was purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ).

Constitution of the Red/Green Visual-Pigment Gene Array.

Gene number was estimated from the ratio of the first gene promoter to the downstream gene promoter, both of which had been amplified by PCR. The nucleotide sequences of the primers used (PF-2 and PR) are shown in Table 1. The cycling parameters were 94°C for 30 sec, 61°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec for 30 cycles. The enzyme used was the Takara Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Kyoto). After the reaction, the mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel (Agarose S, Nippon Gene, Tokyo). The 169-bp product was purified from the gel by using the BandPrep DNA-isolation kit (Amersham Pharmacia), digested with Cfr10I (Takara, recognition sequence = RCCGGY), and separated by electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. The migration patterns were observed by staining the gel with SYBRGold (Molecular Probes). The products from the first gene promoter were expected to give 137- and 32-bp bands, and those from the downstream gene promoters were expected to give 97-, 40-, and 32-bp bands. The fluorescence intensity of the 137- and 97-bp bands was measured in the Epi-light UV detector (EU-1100, Aisin Cosmos R&D, Tokyo), and the gene number was estimated from their ratios [(97 bp + 137 bp)/137 bp]. The validity of the method was confirmed by its application to the PCR products of the cloned promoters of the first gene and downstream genes that were mixed at various ratios (1:1–1:4). The red/green-gene ratios were estimated by the PCR restriction-digestion method that has been described (14).

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR and/or sequencing

| Position | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| First gene promoter | FF | GAGGCGAGGCTACGGAGT |

| Downstream gene promoter | DF-1 | TTAGTCAGGCTGGTCGGGAACT |

| DF-2 | ACCTCCGCCTCCCAGATT | |

| Promoter −190 to −171 | PF-1 | CCAGCAAATCCCTCTGAGCC |

| −128 to −109 | PF-2 | GAGGAGGAGGTCTAAGTCCC |

| −7 to −27 | PFR | CCTGAGGGTCACGGCGCTTTA |

| −7 to −27 | PDR | CCTGAGGGTCACGGTGCTTTA |

| +41 to +21 | PR | GGCTATGGAAAGCCCTGTCCC |

| Intron 1 | 1R | CCACAAAGAAAGAGCACA |

| 1F | CGGTGCTGCAGCCCAGCTCC | |

| Intron 2 | 2R | CGAGCCTGGGCCCCGACTGGC |

| 2F | CCTTTGCTTTGGCTCAAAGC | |

| Intron 3 | 3R | GACCCTGCCCACTCCATCTTGC |

| 3F | TCCTGGGTCACCCCACCCTGCA | |

| Intron 4 | 4R | GACTCATTTGAGGGCAGAGCAGC |

| 4F | TCCAACCCCCGACTCACTATC | |

| Intron 5 | 5R | ACGGTATTTTGAGTGGGATCTGCT |

| Red exon 5 | 5RF | GGTGATGATCTTTGCGTACTGCG |

| Green exon 5 | 5GF | GTGATGGTCCTGGCATTCTGCT |

| Exon 5 | E5F | GGCTGCCCTGCCGGCCT |

| Intron 5 | 5F | GAAATAATCCAAGCCTTCCTC |

| Exon 6 | E6R | GCAGTGAAAGCCTCTGTGACT |

Confirmation of a Normal Genotype.

For the color-deficient subjects who were thought to have a normal genotype, the first gene and downstream genes were amplified separately by the long-range PCR method (14, 15) that uses the TripleMaster polymerase (Eppendorf). The primers FF and E6R were used for the first gene, and primers DF-1 and E6R were used for the downstream genes (Table 1). The reaction mixture (25 μl) contained primers, template DNA (20–50 ng), polymerase enzyme, 400 μM each of dNTPs, and 1× Tuning buffer. The PCR-amplified mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.5% agarose gel (Agarose H, Nippon Gene), and the 15.8-kb (first gene) or 14.5-kb (downstream gene) fragment was purified from the gel. The purified product was used as the template in the second-round PCR for exon 5. The cycling parameters were 94°C for 30 sec, 61°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec for 20 cycles. The 314-bp product was gel-purified and analyzed by single-strand conformational polymorphism (14, 15).

Analysis of the Nucleotide at −71.

The downstream gene promoter, together with exon 1, was amplified by PCR with the primers DF-1 and 1R (Table 1). The cycling parameters were 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec for 25 cycles. A nested PCR was performed by using a portion of the first PCR mixture as the template and with primers PF-1 and PFR (Table 1). Primer PFR, corresponding to the first gene promoter, was used instead of primer PDR, which corresponded to the downstream gene promoter, because it contains an HhaI site that was useful as internal control for the HhaI digestion. Primers PFR and PDR differ in only one nucleotide at position −21 (Table 1). The cycling parameters were 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec for 20 cycles. After the reaction, the mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel, and the 184-bp product was purified from the gel. For examination of the nucleotide at −71, the sequence around which is (−77)TTTGGGAGCTTTT(−65), the purified product was digested with HhaI (Takara) (recognition sequence = GCGC), separated by electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, that was stained with SYBRGold. When the nucleotide at −71 is A, 169- and 15-bp fragments are expected, but when it is C, the 169-bp fragment is expected to be cut into 120- and 49-bp fragments. The presence of −71C was confirmed by sequencing by using primer PF-2.

Long-Range PCR of Intergenic Regions for Second and Third Gene Promoters.

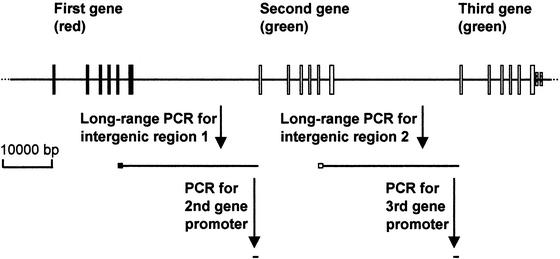

Intergenic region 1, between the red and the following green genes, and intergenic region 2, between the two green genes, were PCR-amplified in the subjects with one red and two green genes (Fig. 1). The primers used were 5RF and PDR for intergenic region 1 and 5GF and PDR for intergenic region 2 (Table 1). The cycling parameters for both were 93°C for 3 min for initial template denaturation, 10 cycles of 93°C for 15 sec and 68°C for 25 min, and then 18 cycles of 93°C for 15 sec and 68°C for 25 min with a 20-sec increment per cycle. The enzyme used for this long-range PCR was the TripleMaster polymerase. After the reaction, the mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.5% agarose gel, and the 27-kb product was purified from the gel. The specificity of the long-range PCR was confirmed by sequencing of exon 5 contained in the product. For this purpose, exon 5 was PCR-amplified by using primers E5F and 5R (20 cycles, annealing temperature at 55°C). The 115-bp product was gel-purified and sequenced by using primer 5R.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the second and third gene promoters. Intergenic region 1 between the first gene and the following gene and intergenic region 2 between the second and third genes were amplified followed by amplification of the second and third gene promoters from the amplified intergenic regions 1 and 2, respectively. We applied this strategy to 31 subjects who had an array consisting of three genes: one red at the first position and two green genes downstream. Long, filled boxes are exons of the first gene (red), long, open boxes are those of the downstream genes (green), and small hatched boxes are exons 4 and 5 of the TEX28 gene. ■, PCR primer specific for red exon 5 (5RF); □, PCR primer specific for green exon 5 (5GF).

The second-round PCR for the promoter was performed by using the purified long-range PCR product as the template and primers PF-1 and PFR. The 184-bp product was processed as described above.

Sequencing of Promoters, Exons, and Exon–Intron Boundaries.

For those deutan subjects confirmed to have a normal genotype, the promoters and six exons, including their flanking introns in the downstream gene(s), were amplified separately from the purified long-range PCR product. In two subjects for whom the long-range PCR for the downstream gene was not successful (A26 and A148), the exons and their flanking introns were amplified directly from their genomic DNA. The primers used for the second-round PCR (20 cycles) are listed in Table 1. Exon 1, together with the promoter region, was amplified with primers DF-2 and 1R (annealing temperature at 55°C), exon 2 with primers 1F and 2R (65°C), exon 3 with primers 2F and 3R (55°C), exon 4 with primers 3F and 4R (60°C), exon 5 with primers 4F and 5R (61°C), and exon 6 with primers 5F and E6R (55°C). The enzyme used was the Takara Taq DNA polymerase. The PCR products were gel-purified and sequenced in both directions by using the DYEnamic ET cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia) and the PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Results

Deutan Subjects.

We studied a subject group of 247 deutans consisting of 102 deuteranopes, 143 deuteranomaly subjects including 8 with pigment-color defect, and 2 unclassified (presumably deuteranomaly) deutans for their visual-pigment genes.

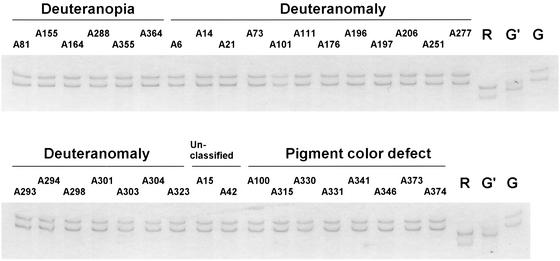

Of the 102 deuteranopes, 76 had an array consisting of a single red gene, but the other 26 had arrays with more than one gene. Analysis using the long-range PCR showed that 6 of 26 had a red gene at the first position (data not shown) and only a green gene(s) downstream (Fig. 2). The phenotypes and genotypes of the deuteranopia subjects with a normal genotype, representing 6% (6/102) of the total population, are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis of downstream gene in deutan subjects. For the 35 deutan subjects thought to have a normal genotype, the downstream gene(s) was amplified by the long-range PCR, and then exon 5, contained in the product, was PCR-amplified and analyzed by single-strand conformational polymorphism. R, red exon 5; G, typical green exon 5; G′, variant green exon 5, where codon 283 is CCC instead of CCA.

Table 2.

Profiles of deutan subjects with a normal genotype

| Category | Subject | Matching range | Gene array | Mutation or nucleotide substitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuteranopia | A81 | 0–73 | R-*G | A−71C |

| A155 | 0–73 | R-G | Asn-94-Lys in green | |

| A164 | 0–73 | R-G-*G | Arg-330-Gln in green | |

| A−71C | ||||

| A288 | 0–73 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A355 | 0–73 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A364 | 0–73 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| Deuteranomaly | A6 | 40–52 | R-*G | A−71C |

| A14 | 0–55 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A21 | 33–35 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A26 | 20 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A73 | 0–60 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A101 | 15–25 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A111 | 35–55 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A148 | 0–48 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A176 | 44–48 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A196 | 48–65 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A197 | 30–45 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A206 | 18–43 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A251 | 25–73 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A277 | 35–52 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A293 | 10–60 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A294 | 28–43 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A298 | 25–60 | R-G-G | None | |

| A301 | 16–37 | R-*G-*G | A−71C | |

| A303 | 0–45 | R-G-G | None | |

| A304 | 38–57 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| A323 | 10–35 | R-*G | A−71C | |

| Unclassified | A15 | ND | R-*G-*G | A−71C |

| A42 | ND | R-G-G | None |

R, red gene; G, green gene;

, position of an A-71C substitution; ND, not done.

In the total group of 145 consisting of 143 deuteranomaly and 2 unclassified subjects, 10 had an array consisting of a single red gene, which is the genotype of deuteranopes. These 10 subjects had a broader matching range, for example 0–65 or 10–73, than the other deuteranomaly subjects. The remaining 135 subjects had more than one gene in the array. Further analysis with long-range PCR showed that 29 of 135 had a red gene at the first position (data not shown) and only a green gene(s) downstream (Fig. 2). In two subjects, A26 and A148, long-range PCR could not be done because of degradation of the DNA, but we believe that they had a normal genotype of one red and one green gene. The phenotypic and genotypic analysis data for the 21 deuteranomaly and 2 unclassified subjects are summarized in Table 2. Data for the eight subjects with pigment-color defect are shown separately in Table 3. These subjects with pigment-color defect were diagnosed as deutans by color-vision tests such as standard pseudoisochromatic plates-1 because the anomaloscopic tests gave normal matching ranges (Table 3). All eight subjects had a normal genotype.

Table 3.

Profiles of subjects with pigment-color defect

| Subject | Gene array | Matching range | Ishihara plates | SPP-1 | HRR plates | TMC plates | Panel D-15 test | Lantern test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A100 | R-*G-*G | 40 | 16/20 | 7/10 | ND | DII | Pass | 8/9 |

| A315 | R-*G | 40–42 | 17/20 | 8/10 | ND | DII | Pass | 8/9 |

| A330 | R-*G | 35–45 | 12/14 | 9/10 | D medium | DIII | Pass | 7/9 |

| A331 | R-*G-*G | 37–43 | 13/14 | 10/10 | D strong | DIII | Pass | 6/9 |

| A341 | R-*G | 40–42 | 10/12 | 9/10 | D medium | DII | Pass | 4/9 |

| A346 | R-*G | 30–40 | 12/14 | 9/10 | D medium | DIII | Pass | 4/9 |

| A373 | R-*G | 35–47 | 11/14 | 6/10 | ND | ND | Pass | 6/9 |

| A374 | R-*G-*G | 38–42 | 17/20 | 9/10 | ND | DII | Pass | 7/9 |

SPP-1, standard pseudoisochromatic plates-1; HRR, Hardy, Rand, and Ritter; TMC, Tokyo Medical College; R, red gene; G, green gene;

, presence of an A−71C substitution; ND, not done; D, deutan deficiency; DII, deutan deficiency, grade II. Denominators are numbers of plates or lights examined, and numerators are numbers of failed plates or lights.

In all 35 deutan subjects shown in Fig. 2, the downstream exons 5 were typical green type (G), rather than the variant green type (G′) with codon 283 of CCC instead of CCA. This was also true for A26 and A148 (data not shown). Because the frequency of the variant green exon 5 is 32% in the Japanese population (14), it is of interest that the variant green exon 5 has never been found in the deutan subjects with a normal genotype.

Among the 247 deutan subjects, a total of 37 (15.0%) had a normal genotype, but only two deuteranopes had missense mutations in the green genes. Specifically, A155 had the mutation Asn94Lys (AAC → AAA) and A164 had Arg330Gln (CGA → CAA). We have already characterized these mutations through expression of the mutated green opsins in cultured cells and spectrophotometric analysis of the reconstituted visual pigments (16). The Asn94Lys mutation gave no absorption, and the Arg330Gln mutation gave only 10–20% absorbance of the wild type.

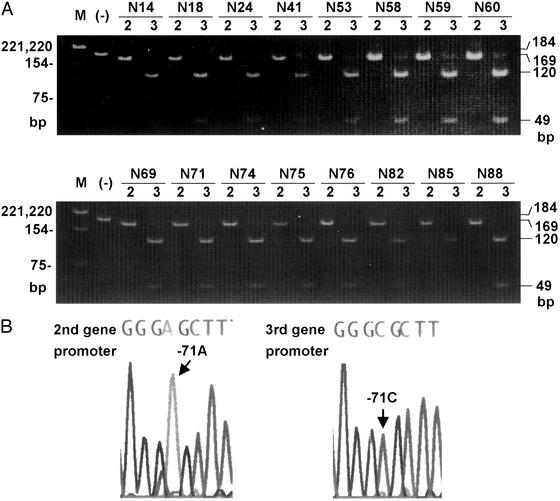

The other 35 subjects had no mutations in either the exons or in the exon–intron boundaries, but 32 subjects including all 8 subjects with pigment-color defect, had an A−71C substitution in the green-gene promoters. The electrophoretic profiles of the HhaI-digested PCR-product for the downstream gene promoter are shown in Fig. 3. Thirty-two subjects had −71C only, 4 subjects (A155, A298, A303, and A42) had −71A only, and A164 had both −71A and −71C. The 32 subjects, therefore, always had −71C in the green gene at the second position irrespective of the number of green genes (as indicated by the asterisks in Tables 2 and 3). In subject A164, −71C was present in the green gene at the third position, but the subject had the deuteranopic phenotype, probably as a result of the Arg330Gln missense mutation (16).

Figure 3.

Analysis of promoter for −71 in deutan subjects with a normal genotype. The downstream gene promoter was amplified by nested PCR. The 184-bp product was gel-purified and digested with HhaI. When A is at −71, the product is cut into 169- and 15-bp fragments, but when C is at −71, the 169-bp fragment is cut into 120- and 49-bp fragments. M, DNA size marker, PBR322-HinfI, sizes are shown on the left; (−), purified PCR product before HhaI digestion.

Analysis of Color-Normal Subjects for −71.

We studied a total of 432 color-normal Asian males for red/green-gene numbers and the −71 position in green genes. The Asian study population consisted of 230 Japanese, 98 Chinese, and 104 Thailanders. None of the 206 (98 + 52 + 56) Asian subjects with one red and one green gene had the −71C substitution (Table 4). However, 83 of the 226 Asian subjects with one red and more than one green genes had the −71C substitution (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analysis of A-71C substitution in males of various ethnic populations

| Gene number | Japanese | Chinese | Thailanders | Caucasians | African Americans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0/98 | 0/52 | 0/56 | 0/21 | 0/4 |

| 3 | 35/89 | 15/32 | 7/39 | 1/24 | 0/6 |

| 4 | 12/29 | 4/13 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 0/3 |

| >4 | 9/14 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/0 | 0/1 |

| Total | 56/230 (24.3) | 19/98 (19.4) | 8/104 (7.7) | 1/50 (2.0) | 0/14 (0.0) |

Denominators are numbers of subjects classified into each category, and numerators are numbers of subjects with −71 C. The frequency of subjects having −71C in each population is shown in parentheses (%). All the Japanese, Chinese, and Thailander subjects and only nine subjects of the Caucasians were color-normal.

We also studied 9 color-normal Caucasian males as well as 41 Caucasian males and 50 African Americans (14 males and 36 females) whose color-vision status was unknown. The −71C substitution was detected in one Caucasian male with one red and two green genes but in none of the African Americans.

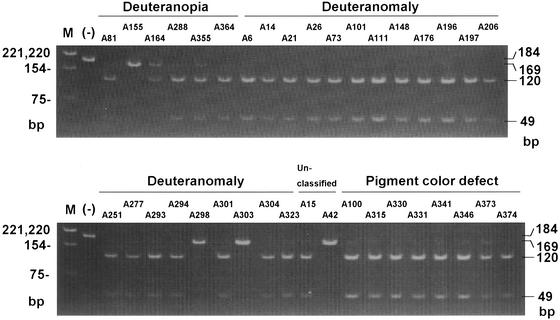

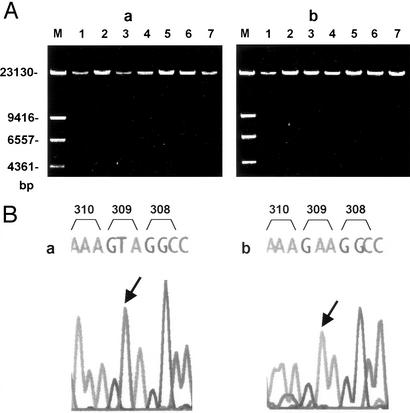

These results suggest that for normal color vision, the −71C should not be present in a green gene at the second position. Because all 35 color-normal Japanese subjects with three genes and −71C had −71A in one green gene and −71C in the other, we determined whether the green gene with −71C is present at the second or at the third position by using the long-range PCR strategy shown in Fig. 1. The regions between the red and the following green genes (intergenic region 1) and between the two green genes (intergenic region 2) were amplified first (Fig. 4A). The specificity of the long-range PCR was confirmed by sequencing of the contained exon 5 around the region downstream of the primer sequence (codon 309, Fig. 4B). The long-range PCR was unsuccessful in 4 of 35 subjects due to degradation of the DNA. The second and third gene promoters then were amplified from the purified long-range PCR products for the intergenic regions 1 and 2, respectively. In all 31 subjects, −71C was present in the third and −71A was present in the second gene promoter. Fig. 5A shows typical electrophoretic profiles for 16 subjects, showing that the −71 position in the second gene promoter was not cut with HhaI (GAGC), but the same position in the third gene promoter was cut (GCGC). The results were confirmed by sequencing, and typical electropherograms are shown in Fig. 5B.

Figure 4.

Long-range PCR for the intergenic regions. (A) Typical electrophoretic profiles of the long-range PCR product. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide. (a) Intergenic region 1 products; (b) intergenic region 2 products. Templates were from seven color-normal males (1–7). M, DNA size marker, λ-DNA-HindIII (100 ng). (B) Sequencing of exon 5, contained in the long-range PCR product, using primer 5R. (a) Exon 5 contained in the product for the intergenic region 1 showing that it is of the red type in which codon 309 is GTA (TAC for tyrosine in the sense strand); (b) exon 5 contained in the product for the intergenic region 2 showing that it is of the green type in which codon 309 is GAA (TTC for phenylalanine in the sense strand). 308, 309, and 310 are codons, and arrows indicate the position of codon 309-2.

Figure 5.

(A) Analysis of promoter for −71 in color-normal subjects. Long-range PCR for intergenic regions 1 and 2 was applied to the color-normal Japanese subjects (N-numbered) who had one red gene and two green genes and −71A in one green gene and −71C in the other. The promoter region contained in each PCR product was amplified by the second-round PCR. The 184-bp product was gel-purified and digested with HhaI for the presence of −71C. When A is at −71, the product is cut into 169- and 15-bp fragments, but when C is at −71, the 169 fragment is cut into 120- and 49-bp fragments. M, DNA size marker, PBR322-HinfI, sizes are shown on the left; (−), purified PCR product before HhaI digestion; 2, second gene promoter digested with HhaI; 3, third gene promoter digested with HhaI. (B) Sequencing of promoter contained in the long-range PCR product. The promoter amplified from the long-range PCR product was sequenced by using primer PF-2.

Discussion

Color-Deficient Subjects with a Normal Genotype.

In this study we showed that the Japanese males with congenital deutan color-vision deficiency often (15.0%, 37/247) had a normal genotype. We also found 5 subjects with a normal genotype among the 94 Japanese protan subjects (data not shown). Thus, the frequency of color-deficient subjects with a normal genotype is high. Subjects with color deficiency but a normal genotype have also been found among Caucasian males but at a lower frequency of 5.6%, as determined in a population of 142 subjects. The specific breakdown of the 8 patients with normal genotype was as follows: 3 deuteranomaly subjects in the 64 color-deficient subjects (12, 17), 1 protanope in the 28 color-deficient subjects (18), and 4 deuteranomaly subjects in the 50 color-deficient subjects (19). Three of the eight subjects had a Cys203Arg mutation, but the remaining five had no mutations in the exons, the exon–intron boundaries, or in the promoters including −71C. In contrast, the Japanese color-deficient subjects with a normal genotype never had the Cys203Arg mutation.

Neitz and Neitz (20) also found 14 subjects with one red and one or more green genes in a study of 115 subjects who had been considered to be color-deficient. Two subjects were deuteranopes with a Cys203Arg mutation in the green genes (21) and two were protans. The remaining 10 subjects were infants and could not be classified as protans or deutans. Nathans et al. (2) identified one subject having a red gene among 8 protan subjects, and Shevell et al. (22) reported 2 subjects that were thought to have a normal genotype among 13 deutan subjects. In our own studies, we identified eight protan subjects, supposedly with a normal genotype but subsequent analysis showed that three had a green gene at the first position and the red gene downstream. Thus, the combination of one red and one or more green genes does not always predict a normal genotype. It was difficult sometimes to determine genotypes in deutan subjects. For example, in a case where the gene number was 2.5 and the red/green ratio was 1.5:1, discrimination between arrays of red–green and red-hybrid red–green was difficult. Therefore, it is important to use the long-PCR method for the first gene identification, as well as the downstream gene(s), for confirmation of a normal genotype.

A−71C Substitution in Deutan Subjects with a Normal Genotype.

Among the 37 deutan subjects with a normal genotype in our study, 32 (86.5%) had an A−71C substitution in the green gene at the second position in the array. All eight subjects with pigment-color defect had the −71C substitution. The high occurrence of the −71C substitution indicated its close association with deutan color-vision deficiency.

One explanation for the importance of the −71C in the etiology of deutan deficiency may be that the substitution itself reduces or abolishes gene expression. The −71C substitution results in a change of the promoter sequence from AG to CG. The cytosine base in the dinucleotide CG is a target for DNA methylation, which subsequently suppresses the expression of corresponding gene (23). Alternatively, the substitution may interfere with the binding of a transcription factor(s), although −71A is not evolutionarily conserved (24). Another explanation may be that the −71C substitution itself may not be responsible for deutan deficiency but is in linkage disequilibrium with a causal mutation. There is a perfect linkage between the −71C substitution and the typical green-gene exon 5 with codon 283 of CCA (Fig. 2). The causal but as-yet-unidentified mutation may also be in a tight linkage with −71C. However, neither of these explanations accommodates the diverse phenotypes, from the most severe form (deuteranopia) to the mildest form (pigment-color defect), in the deutan subjects with a normal genotype and −71C. Therefore, the role of the −71C in the etiology of deutan deficiency requires further study.

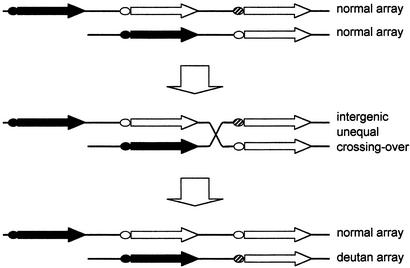

It has been reported that a green-gene deletion (2, 12) or the presence of a 5′ green–red hybrid gene (2, 8, 9, 12, 18, 19) is associated with deutan deficiency. The green-gene deletion is thought to result from unequal crossing over between the red–green intergenic region and TEX28 gene, which is present immediately downstream of the visual-pigment gene array (25). The 5′ green–red hybrid gene is thought to arise from unequal crossing over between the intragenic regions. We propose that in Japanese and other Asian populations, green genes with −71C at the third position or further downstream in color-normal subjects comprise a reservoir that cause deutan color-vision deficiency by unequal crossing over between the intergenic regions as depicted in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic of hypothesis for intergenic unequal crossing-over as a cause of deutan deficiency. ●, first gene promoter; ○, downstream gene promoter with −71A; , downstream gene promoter with −71C; ➞, red gene; ➯, green gene. If two normal arrays, one of which has −71C in the green gene at the third position, undergo intergenic unequal crossing-over, one of them becomes an array in which the green gene with −71C is present at the second position.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Professor Kazutaka Kani (Department of Ophthalmology, Shiga University of Medical Science) for his helpful advice and discussions. We thank Mr. Masashi Suzaki (Central Research Laboratory, Shiga University of Medical Science) for his technical help. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan 14571667 (to S.Y.) and 12770953 (to S.O.).

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Nathans J, Thomas D, Hogness D S. Science. 1986;232:193–202. doi: 10.1126/science.2937147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathans J, Piantanida T P, Eddy R L, Shows T B, Hogness D S. Science. 1986;232:203–210. doi: 10.1126/science.3485310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vollrath D, Nathans J, Davis R W. Science. 1988;240:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.2837827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drummond-Borg M, Deeb S S, Motulsky A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:983–987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winderickx J, Battisti L, Motulsky A G, Deeb S S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9710–9714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deeb S S, Alvarez A, Malkki M, Motulsky A G. Hum Genet. 1995;95:501–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00223860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi T, Motulsky A G, Deeb S S. Nat Genet. 1999;22:90–93. doi: 10.1038/8798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neitz J, Neitz M, Jacobs G H. Nature. 1989;342:679–682. doi: 10.1038/342679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neitz M, Neitz J, Jacobs G H. Vision Res. 1995;35:2095–2103. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjoberg S A, Neitz M, Balding S D, Neitz J. Vision Res. 1998;38:3213–3219. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagstrom S A, Neitz M, Neitz J. J Opt Soc Am A. 2000;17:527–537. doi: 10.1364/josaa.17.000527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deeb S S, Lindsey D T, Hibiya Y, Sanocki E, Winderickx J, Teller D Y, Motulsky A G. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:687–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jørgensen A L, Deeb S S, Motulsky A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6512–6516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi S, Ueyama H, Tanabe S, Yamade S, Kani K. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2001;45:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(00)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oda S, Ueyama H, Tanabe S, Tanaka Y, Yamade S, Kani K. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:767–773. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.21.4.767.5544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueyama H, Kuwayama S, Imai H, Tanabe S, Oda S, Nishida Y, Wada A, Shichida Y, Yamade S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:205–209. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winderickx J, Sanocki E, Lindsey D T, Teller D Y, Motulsky A G, Deeb S S. Nat Genet. 1992;1:251–256. doi: 10.1038/ng0792-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crognale M A, Teller D Y, Motulsky A G, Deeb S S. Vision Res. 1998;38:3377–3385. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagla W M, Jägle H, Hayashi T, Sharpe L T, Deeb S S. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:23–32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neitz M, Neitz J. Color Res Appl. 2001;26:S239–S249. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollinger K, Bialozynski C, Neitz J, Neitz M. Color Res Appl. 2001;26:S100–S105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shevell S K, He J C, Kainz P, Neitz J, Neitz M. Vision Res. 1998;38:3371–3376. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng H-H, Bird A. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:158–163. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaaban S A, Deeb S S. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1998;39:885–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna M C, Platts J T, Kirkness E F. Genomics. 1997;43:384–386. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]