Abstract

Objectives

To ascertain the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and its association with the disease.

Design

Systematic review of studies reporting the prevalence of H pylori in patients with and without gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Data sources

Four electronic databases, searched to November 2001, experts, pharmaceutical companies, and journals.

Main outcome measure

Odds ratio for prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Results

20 studies were included. The pooled estimate of the odds ratio for prevalence of H pylori was 0.60 (95% confidence interval 0.47 to 0.78), indicating a lower prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies. Location seemed to be an important factor, with a much lower prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in studies from the Far East, despite a higher overall prevalence of infection than western Europe and North America. Year of study was not a source of heterogeneity.

Conclusion

The prevalence of H pylori infection was significantly lower in patients with than without gastro-oesophageal reflux, with geographical location being a strong contributor to the heterogeneity between studies. Patients from the Far East with reflux disease had a lower prevalence of H pylori infection than patients from western Europe and North America, despite a higher prevalence in the general population.

What is already known on this topic

The relation between H pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is controversial

Studies on the prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease have given conflicting results

Recent guidelines recommend eradication of H pylori in patients requiring long term proton pump inhibitors, essentially for reflux disease

What this study adds

Despite heterogeneity between studies, the prevalence of H pylori was significantly lower in patients with than without gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Further well designed studies are required to establish the clinical relevance of the findings, particularly in eradication therapy

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is a common condition affecting 25-40% of the population.1 It is managed mainly in primary care and is associated with the largest prescribing cost in the NHS.2 Although there is good evidence that infection with H pylori is the principal cause of peptic ulcer disease, there is uncertainty about the organism's role in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Treating H pylori infection is effective in healing duodenal ulcers.3 The effect of eradication of the organism in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is less clear, with some reports suggesting that this might be counterproductive and that H pylori infection might protect against the disease.4,5 However, the recent Maastricht 2 guidelines on the management of patients with H pylori infection recommend eradication in those with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who are likely to require long term proton pump inhibitor therapy.6 This is because profound acid suppression may accelerate the progression of H pylori induced atrophic gastritis, increasing the potential risk of cancer.

The evidence for an association between H pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease remains mixed and largely uncertain. Studies evaluating the presence or absence of H pylori on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease have often had drawbacks in design and have given conflicting results.7,8 Fundamentally it is not certain whether there are differences in the prevalence of H pylori between patients with and without gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.9–13

We conducted a systematic review to establish the overall prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and to determine if this is significantly different from patients without the disease. This is important for determining if patients with the disease differ and to quantify the extent of infection. This topic is also of relevance because of the large numbers of patients in the community taking long term proton pump inhibitors, mostly for reflux. The determination of H pylori status in these patients has so far not been a clinical issue; gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is commonly diagnosed and treated in primary care on the basis of a clinical history alone.

Methods

We included studies to November 2001 fulfilling certain eligibility criteria (box) by searching Medline, Embase, Cinahl, and Cochrane, using subject terms and text words. Bibliographies of retrieved studies were reviewed, experts in six countries and pharmaceutical companies contacted (see bmj.com), and general medical and major gastroenterology journals searched over the previous year.

Eligibility and quality criteria for inclusion in systematic review

Studies with a comparator, control, or reference group

Patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease should have undergone gastroscopy.

Included:

Patients with endoscopically proved oesophagitis

Patients with normal appearance of oesophagus on endoscopy and with confirmation of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease either by pH studies or histology

Excluded:

Patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom other confirmation of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease by pH studies or histology of the oesophagus was not available

Patients with normal endoscopy result and typical reflux symptoms but confirmation by pH studies or histology not available or confirmed

Patients known or discovered to have Barrett's oesophagus

Patients with confirmed peptic ulcer disease

Patients who had received proton pump inhibitors within the previous two weeks or undergone eradication of H pylori

Comparator group (one or more of the following)

Normal endoscopy result and absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Healthy asymptomatic volunteers

Absence of pathological reflux on pH monitoring—that is, oesophageal pH is <4 for more than 3.5% of total recorded time, or as defined by author of the study

Normal endoscopy result and absence of oesophagitis on histology

Quality criteria

Documentation of how cases were obtained

Appropriateness of comparator

Similar data collection for cases and comparator group

Similar H pylori testing for cases and comparator group

Basic data adequately described

Statistical methods described and significance levels assessed

Assessment of eligibility and trial quality

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease was defined according to published definitions.14–17 These comprised two categories, both in patients who had heartburn or reflux as the predominant symptoms. The first was the presence of endoscopically defined oesophagitis and the second, when endoscopy did not show oesophagitis, a positive result for pH monitoring with or without oesophagitis on histology.

Two investigators independently reviewed the papers according to the predefined criteria (see box). Abstracts were included only if they met the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. Quality assessments focused on whether the methods for obtaining cases and controls, data collection, and H pylori testing were stated.

Data extraction

AR collated data from eligible studies on standardised forms, which were checked by SC. Data on the prevalence of H pylori in various grades of oesophagitis and the absence of visible reflux disease on endoscopy were recorded as reported, but for analysis the overall prevalence of H pylori in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease was used.

Data synthesis

Each of the 20 included studies was summarised according to its odds ratio, with an odds ratio of less than one indicating a higher prevalence of H pylori among controls than among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Results were pooled with a fixed effect (Mantel-Haenszel) model, which was assessed with a test of homogeneity and a funnel plot.18 Odds ratios were pooled with a random effects model in cases of substantial heterogeneity.19 The statistical analysis was performed with the free package R, and the rmeta subpackage contributed by Thomas Lumley (University of Washington).20

Results

Our initial search identified 654 articles, but only 45 evaluated the prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Thirty seven of these met the eligibility criteria; 16 were excluded after further scrutiny (see table A on bmj.com),7,9,13,21–33 and one was excluded because of overlap with a study by the same lead author (the proportions between the two studies were so close that there was virtually no difference in results; see table A on bmj.com).34,35 This left 20 studies for review, totalling 4134 patients, of whom 58.5% (n=2418) were in control groups (table).10,35–53

Prevalence of H pylori infection

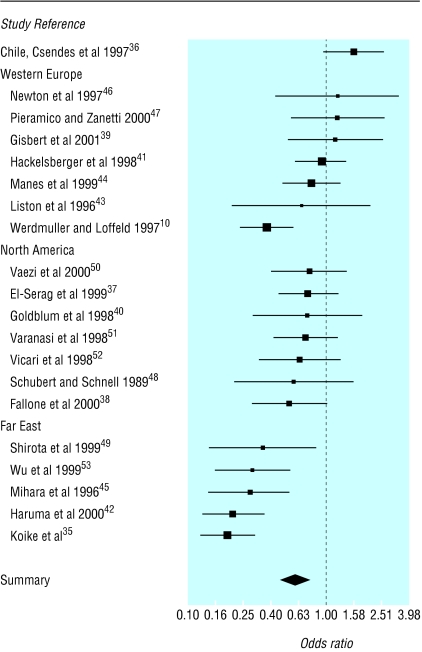

The average prevalence of H pylori infection in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease was 38.2% (range 20.0-82.0%) compared with 49.5% (29.0-75.6%) in the comparator group. Four studies showed a higher prevalence of H pylori infection among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, but not significantly so (fig 1 and table B on bmj.com).36,39,46,47 The remaining studies showed a lower prevalence among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, significantly so in six studies.10,35,42,45,49,53 The pooled odds ratio was 0.58 (95% confidence interval 0.51 to 0.66), indicating a lower prevalence of H pylori infection among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (heterogeneity test: χ2=83.01, df=19, P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for prevalence of H pylori infection, grouped by geographical location. Large boxes indicate studies with small standard errors (essentially larger sample sizes) and vertical dotted line indicates no difference between groups

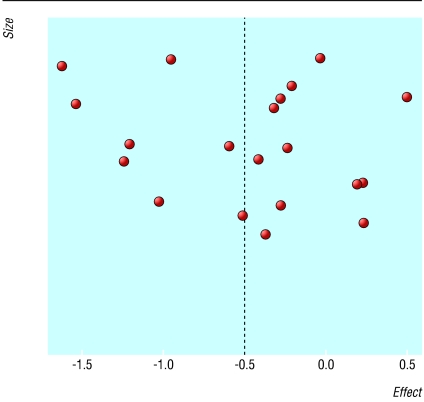

We found no clear evidence of publication bias (fig 2): nor would any be expected in this context. Because of the presence of substantial heterogeneity, the studies were pooled with the DerSimonian-Laird random effects model (summary odds ratio 0.60, 0.47 to 0.78), which showed weaker but still strong evidence of a lower prevalence of H pylori infection among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Figure 2.

Size and effect of results from eligible studies of prevalence of H pylori infection in patients with and without gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Statistical heterogeneity was investigated by year of study (no effect) and by location. Five studies were of patients from the Far East,35,42,45,49,53 seven of patients from North America,37,38,40,48,50–52 and seven of patients from western Europe.10,40,42,44,45,47,48 One further study originated from Chile.36 Some similarities were found in results for studies from particular geographical locations (fig 1). When the three main groups were analysed separately, the results for western Europe gave an odds ratio of 0.76 (0.61 to 0.96) and a test for heterogeneity of χ2=14.01, df=6, P=0.030. One study seemed to dominate the analysis, but repeating the analysis after excluding this study gave an odds ratio of 0.97 (0.75 to 1.27) and a test for heterogeneity of χ2=1.8, df=5, P=0.88.10 The evidence for western Europe is therefore equivocal.

Consistent evidence was found for a lower prevalence of H pylori infection among both North American patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (odds ratio 0.70, 0.55 to 0.9; test for heterogeneity, χ2=0.92, df=6, P=0.99) and patients from the Far East with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (0.24, 0.19 to 0.32 and χ2=2.36, df=4, P=0.670). A single study from South America found a higher prevalence.36 Differences in location may explain much of the heterogeneity among the studies. Some of the remaining heterogeneity may be a product of clinical heterogeneity—for example, differences in methods of H pylori testing, pH measurements, and endoscopic classification of oesophagitis.54

Discussion

Our systematic review found a significantly lower prevalence of H pylori infection among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease than among those without the disease, geographical location being an important determinant. Although the results we found were based on studies with a comparator group, there were significant differences between study design (prospective or retrospective case-control, trial), study population, identification of cases and controls, inclusion and exclusion criteria, matching of cases and controls, and methods of testing for H pylori. Our results therefore need to be interpreted with caution.

Most of the participants underwent endoscopy for clinical reasons and thus did not constitute a population group as such, although we discovered three community based studies.41,42,44 Ascertaining the prevalence of H pylori thus depended on a proportion of patients who were being investigated for suspected lesions. This is unlikely to have substantially compromised our results because we excluded patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who had negative results for endoscopy or pH testing.

Given that there was substantial heterogeneity between the studies, we acknowledge issues about the appropriateness of reporting a pooled odds ratio. On further exploration we did find a possible difference between the Far East and North America or western Europe in prevalence of H pylori infection in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; a single study from South America gave a higher prevalence.36 This seems to indicate that the prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is lower in countries where the prevalence of H pylori in the general population is high. Reasons are unclear and may be related to dietary or genetic factors. Four studies reported a higher prevalence among patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, but in only one was the difference significant.36 Reasons are uncertain but may partly be related to factors such as study design, selection of cases and controls, and method of testing for H pylori. Again, presenting data as pooled estimates of odds ratios for geographical locations may give the impression of post hoc confirmatory analyses, but we strongly believe that there is a location effect evident in these data and that the prevalence has different patterns within locations.

We did not separately analyse the prevalence of H pylori infection in males and females. These data were not obtainable in many studies and, when available, there was no reported difference. We excluded patients with Barrett's oesophagus because we thought that this condition merited a systematic review in its own right.

The clinical relevance of a lower prevalence of H pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is unclear. Some studies have shown that H pylori may be protective against gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and that infected patients may have a less severe form of the disease.4,5 Evidence is also conflicting on the effect of H pylori infection on the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors. One study found that patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and H pylori infection responded significantly better to proton pump inhibitors than those without the infection.8 Another trial found that patients not infected with H pylori did not need higher doses of acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors to stay in remission.7 Evidence shows that H pylori induces atrophic gastritis in the presence of long term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors, and recent guidelines have advocated eradication of H pylori in patients receiving long term proton pump therapy.6,55

We are unable to definitively comment on the benefit or possible detriment of H pylori eradication in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; a further review of this is in preparation. Our findings add insight into the complex relation between H pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Clearly, more, well designed, prospective, large scale, case-control studies and trials are required to determine the epidemiological relation between H pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and the clinical implications of this association.

Supplementary Material

Table.

Studies included in systematic review

| Reference

|

Type of study

|

Participants

|

Intervention

|

Outcome

|

Comments or conclusions

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Werdmuller and Loffeld 199710 | Descriptive, prospective | Consecutive patients undergoing endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract for upper abdominal symptoms or reflux symptoms. Cases (n=240, of which 118 patients with proved gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included). Rest with hiatus hernia and no reflux oesophagitis or with Barrett's oesophagus excluded. Reference group (n=399): normal endoscopy and presumed absence of typical reflux symptoms | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract, H pylori testing by histology (haematoxylin and eosin stain), culture, quick urease test, and serology (not all tests in every patient) | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (29%) and reference group (51%) | We assumed from details that patients in reference group do not have reflux disease |

| Koike et al 199935 | Case-control, prospective | Patients were self referred and referred by doctor. Cases (n=175): patients with reflux oesophagitis. Controls: age-sex matched, randomly selected, who visited hospital, were asymptomatic, and had normal endoscopy results | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract. H pylori testing by histology, rapid urease test, and serology. Atrophic gastritis assessed by updated Sydney system, and serum pepsinogen measured | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (34%) and controls (72%) | |

| Csendes et al 199736 | Case-control, prospective, prevalence study | Cases (n=136): patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (reflux oesophagitis, negative reflux disease on endoscopy) symptoms of at least three years' duration. Controls (n=190): patients needing endoscopy, none of whom had symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls, H pylori testing by histology, pH-metry in all cases of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, no pH-metry in controls | H pylori prevalence in patients with reflux oesophagitis, reflux disease negative on endoscopy, Barrett's oesophagus, and controls. No significant difference in H pylori prevalence between patients with patients with reflux oesophagitis (32%), reflux disease negative on endoscopy (25%), and controls (29%). Also no difference in age and sex distribution between reflux patients and controls | Exclusion of peptic ulcer not clearly stated |

| El-Serag et al 199937 | Descriptive, prospective | Patients referred for elective endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract. Cases (n=154, of which 116 patients were included, 38 excluded because of Barrett's oesophagus): all patients with erosive oesophagitis. Controls (n=148): Patients with normal endoscopy result and absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls, H pylori testing by haematoxylin and eosin stain | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (31%) and controls (43%) | This study looked at protective effect of corpus gastritis against reflux oesophagitis. We excluded Barrett's oesophagus from our analysis |

| Fallone et al 200038 | Descriptive, prospective. | Patients scheduled for endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract. Cases (n=327, of which 81 patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included). Rest were classified into non-ulcer disease, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and therefore excluded. Patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease had reflux oesophagitis or negative reflux disease on endoscopy. Comparator group (n=78): patients in whom there were no symptoms of gastro-oeosophageal reflux disease and in whom indications for endoscopy were multiple. All had normal oesophagus or findings unrelated to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract; H pylori testing by histology and culture; detection of specific genes or gene sequence within H pylori and detection of CagA antibodies | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (33%) and comparator group (48%). Prevalence of CagA, CagE, vacA S1 genotypes, and CagA antibody determined in cases and comparator group | Some patients with reflux disease negative on endoscopy but reflux not proved may have been included in our prevalence data. This study concluded that gastro-oesophageal reflux disease was associated with a significantly lower rate of vacA S1 genotype than in controls |

| Gisbert et al 200139 | Descriptive, prospective, prevalence | Consecutive patients undergoing 24 hour oesophageal pH monitoring in motility unit because of symptoms suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Cases (n=56): typical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and positive pH findings. Controls (n=44): symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease but negative pH findings | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract, 24 hour oesophageal pH monitoring and H pylori testing by histology and rapid urease test | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (57%) and controls (52%) | Comparator group may represent patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia |

| Goldblum et al 199840 | Case-control, prospective | Cases (n=58): patients with classic symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease enrolled into study. Controls (n=27): patients undergoing endoscopy for reasons other than symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's oesophagus, peptic ulcer disease, or dyspepsia | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls; H pylori testing by histology (haematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain) and serology | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (41%) and controls (48%). Prevalence of carditis and intestinal metaplasia of cardia in cases and controls also determined | This study also concluded that cardia inflammation and cardia intestinal metaplasia are associated with H pylori infection |

| Hacklesberger et al 199841 | Case-control, prospective | Cases (130 of 171 included, remaining 41 had associated peptic ulcer disease): consecutive Caucasian patients undergoing elective endoscopy. Controls (n=227): asymptomatic volunteers or patients attending for other reasons and without any symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases only. H pylori testing by histology and rapid urease test in cases, 13-carbon urease breath test | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (38%) and controls (39%) | Different methods of H pylori testing in cases and controls. No endoscopy in controls |

| Haruma et al 200042 | Retrospective case-control | Of 6205 patients undergoing endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract between defined periods, 229 were defined as having reflux oesophagitis. Of these, 95 met authors' inclusion criteria. Controls (n=190): healthy, asymptomatic, age-sex matched selected from among 608 healthy individuals who had undergone routine healthcare check for gastric cancer | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls; H pylori testing by Giemsa stain and serology. Inflammation, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia were evaluated using updated Sydney system. Serum gastrin and pepsinogen concentrations determined | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (41%) and controls (76%) | The authors found significant low prevalence of H pylori in patients over 60 but not under 59 with reflux oesophagitis, when compared with age-sex matched controls |

| Liston et al 199643 | Descriptive, prospective, prevalence | Consecutive patients admitted for gastroscopy recruited regardless of reasons for procedure. Main reasons were anaemia, reflux symptoms, and epigastric pains. Cases (n=37): reflux oesophagitis (macroscopic or microscopic). Comparator group (n=33): normal endoscopy result and no evidence of histological oesophagitis | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract; H pylori testing by histology, rapid urease test, serology, and 13-carbon urease breath test | H pylori prevalence in patients with reflux oesophagitis (76%) and comparator group (82%). Patterns of gastritis described in the two groups | Although exclusion of patients with peptic ulcer disease had not been clearly stated, on reading the paper, we assumed this to be the case |

Table.

Studies included in systematic review contd

| Reference

|

Type of study

|

Participants

|

Intervention

|

Outcome

|

Comments or conclusions

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manes et al 199944 | Case-control, prospective, prevalence | Cases (105 of 202, of which 105 patients with proved gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included): consecutive patients with typical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease lasting more than six months. Peptic ulcer cases excluded. Controls (n=200): healthy asymptomatic blood donors and patients with functional non-specific abdominal problems with normal endoscopy result except for signs of chronic gastritis | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases only. H pylori testing by histology or rapid urease test in cases and serology in controls | H pylori prevalence in patients with erosive reflux oesophagitis (32%), reflux disease negative on endoscopy (62%), and control group (40%). Also patterns of gastritis, H pylori colonisation, and dyspepsia symptoms in patients with reflux disease negative on endoscopy and reflux oesophagitis compared | We excluded patients with Barrett's oesophagus (as stated in our protocol) and also reflux disease negative on endoscopy (not proved to have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) from our analysis. Different methods of H pylori testing in cases and controls, no endoscopy in controls |

| Mihara et al 199645 | Case-control, prospective, prevalence | Cases (n=70): patients with reflux oesophagitis. Controls (n=70): age-sex matched, no symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and normal endoscopy result | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract, H pylori testing by Giemsa stain and serology, gastritis and atrophy scores, and serum pepsinogen levels | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (37%) and controls (67%). Gastritis, atrophy scores, and serum pepsinogen 1, pepsinogen 2 levels and ratios in cases and controls also determined | Abstract |

| Newton et al 199746 | Case-control, prospective, prevalence | Cases (83, of which 25 patients with proved gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included): patients referred for endoscopy divided into four groups. (reflux oesophagitis, duodenal ulcer, or both, and Barrett's oesophagus). Controls (n=25): asymptomatic patients with anaemia referred for endoscopy | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls. H pylori testing by histology and CLO test | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (42%) and controls (36%). H pylori colonisation and distribution assessed in different patient groups | We excluded patients with Barrett's oesophagus, duodenal ulcer, and duodenal ulcer with reflux oesophagitis from our analysis |

| Pieramico and Zanetti 200047 | Case-control, prospective | Cases (122, of which 54 patients with proved gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included, 68 patients with negative reflux disease on endoscopy excluded because reflux not proved): consecutive patients referred for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms to endoscopy unit. Controls (n=49): patients who underwent endoscopy in same period as cases for reasons other than symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's oesophagus, active or previous peptic ulcer disease, gastric or oesophageal neoplasms, or dyspepsia | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls; H pylori testing by Giemsa stain in cases and controls | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (44%) and controls (38%) | Grade 0 (reflux disease negative on endoscopy, 68 patients) were not proved to have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, hence we excluded them from our analysis |

| Schubert and Schnell 198948 | Descriptive, prospective | All consenting patients referred for endoscopy between defined periods. Cases (170, of which 31 patients with proved gastro-oesophageal reflux disease included). Rest were classified into several diagnostic groups (duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastritis, duodenitis) and therefore excluded. Control or comparator group (n=42): patients with absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and normal endoscopy result | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract; H pylori testing by histology, rapid urease test, and culture | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (26%) and comparator group (40%) | Some patients with reflux disease negative on endoscopy but reflux not proved may have been included in our prevalence data |

| Shirota et al 199949 | Descriptive, retrospective | Random selection of cases and controls from patients who underwent endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract between defined periods. Cases (n=73): reflux oesophagitis (mild, severe). Controls (n=28): normal endoscopy result and presumed absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract, H pylori testing by culture, urease test, and serology, serum pepsinogen levels, and oesophageal manometry | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (36%) and controls (61%). Pepsinogen 1 to pepsinogen 2 ratios determined to assess severity of atrophic gastritis | We assumed from details that patients in control group did not have symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Authors concluded that low prevalence of H pylori might result in milder grade of atrophic gastritis and consequently exacerbate reflux oesophagitis |

| Vaezi et al 200050 | Descriptive, prospective | Patients undergoing endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract. Based on questionnaire before endoscopy and endoscopy findings, patients were grouped into cases: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (n=108), short and long-segment Barrett's oesophagus, and controls (n=60). Controls had normal endoscopy and no symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract. H pylori testing by Giemsa stain, serology to determine IgG response to H pylori whole cell antigen and to CagA using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay | H pylori and CagA prevalence in cases (gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, short segment and long segment Barrett's oesophagus) and controls. H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (36%) and controls (42%) | Authors concluded that CagA positive H pylori strains might protect against Barrett's oesophagus. We excluded patients with Barrett's oesophagus from our analysis |

| Varanasi et al 199851 | Descriptive, retrospective | Review of records of all patients (>18 years) who had endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract and rapid urease testing. Cases (n=54): gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (reflux oesophagitis or proved negative reflux disease on endoscopy, typical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, normal endoscopy, and histological esophagitis) and Barrett's oesophagus. Comparator (n=257): normal endoscopy and presumed absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract; H pylori testing by rapid urease test in all, histopathology and serology in some | H pylori prevalence in patients with and without gastro-oesophageal reflux disease as well as stratifying for presence or absence of peptic ulcer disease in each group. H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (29%) and controls (34%) | We excluded patients with Barrett's oesophagus and cases of reflux oesophagitis associated with peptic ulcer disease from our analysis. Authors found no variability of H pylori between different groups of patients with reflux oesophagitis |

| Vicari et al 199852 | Prospective, case-control | Cases: patients with classic symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (153, of which 84 patients included and 59 with Barrett's oesophagus excluded) enrolled into study. Controls: patients undergoing endoscopy for reasons other than symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's oesophagus, peptic ulcer disease, or dyspepsia | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in cases and controls; H pylori testing by histology (haematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain) and serology | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (36%) and controls (46%). CagA positivity status also determined in cases and controls | Some patients with reflux disease negative on endoscopy but reflux not proved may have been included in our prevalence data. We excluded patients with Barrett's oesphagus from our analysis |

Table.

Studies included in systematic review contd

| Reference

|

Type of study

|

Participants

|

Intervention

|

Outcome

|

Comments or conclusions

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al 199953 | Case-control, prospective. | Cases (106, of which we included 66 and excluded 40 with reflux disease negative on endoscopy in whom diagnosis of reflux disease was not proved): Patients with typical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and reflux oesophagitis. Controls (n=120): absence of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, absence of dyspepsia, and recruited from general medical clinics and day care centres without any evidence of gastrointestinal disease | Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract in H pylori positive cases, H pylori testing by serology in cases and controls, Giemsa stain for H pylori, haematoxylin and eosin stain for gastritis, and intensity of inflammation and bacterial colonisation by the updated Sydney system in H pylori positive cases | H pylori prevalence in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (32%) and controls (61%). Histological assessment of gastritis and H pylori colonisation in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease also studied | We excluded patients with reflux disease negative on endoscopy from our analysis |

Footnotes

Funding: The Northern and Yorkshire NHS Executive (research and development) funded this review through a regional research fellowship to AR. Abbott Pharmaceuticals provided additional financial support. This review is a part of AR's PhD.

Competing interests: APSH is coauthor of the Maastricht 2 guidelines on the management of H pylori infection; he has received research funding from Abbott Pharmaceuticals and conference travel costs and honoraria for advisory groups to several manufacturers of proton pump inhibitors over the past five years. AR has received research funding from Wyeth.

Details of the searches and tables of the excluded studies and prevalences appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Jones R. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995;211:35–38. doi: 10.3109/00365529509090292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Health Economics. Health expenditures in the UK. London: Stationery Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosking SW, Ling TK, Chung SC, Yung MY, Cheng AF, Sung AF, et al. Duodenal ulcer healing by eradication of Helicobacter pylori without anti-acid treatment: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1994;343:508–510. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. H pylori and cagA. Relationships with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis and its complications. Helicobacter. 1998;3:145–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter JE, Falk GW, Vaezi MF. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: the bug may not be all bad. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1800–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfertheiner P, Magraud F, O'Morain C, Hungin APS, Jones R, Axon A, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht 2-2000 consensus report. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2002;6:167–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Eskes SA, Meuwissen SG. Helicobacter pylori and the efficacy of omeprazole therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.982_e.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtmann G, Cain C, Malfertheiner P. Gastric Helicobacter pylori infection accelerates healing of reflux esophagitis during treatment with the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng EH, Bermanski P, Silversmith M, Valenstein P, Kawanishi H. Prevalence of Campylobacter pylori in esophagitis, gastritis, and duodenal disease. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1373–1375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werdmuller BF, Loffeld RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection has no role in the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:103–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1018841222856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Koster E, Ferhat M, Deprez C, Deltenre SM. H pylori, gastric histology and gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 995;108(suppl):A81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boixeda D, Gisbert JP, Canton R, Alvarez BI, Gil GL, Martin de AC. Is there any association between Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic esophagitis? Med Clin (Barc) 1995;105:774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCallum RW, De Luca V, Marshall BJ, Prakash C. Prevalence of campylobacter-like organisms in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease versus normals. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:A1524. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anonymous-French-Belgian consensus conference on adult gastro-oesophageal reflux disease “diagnosis and treatment”: report of a meeting held in Paris, France, on 21-22 January 1999. The jury of the consensus conference. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:129–137. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dent J, Jones R, Kahrilas P, Talley NJ. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. BMJ. 2001;322:344–347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7282.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1434–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1123_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroes RM, Numans ME, Jones RH, de Wit NJ, Verheij TJM. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Comparison and evaluation of existing national guidelines and development of uniform guidelines. Eur J Gen Pract 1999:88-97.

- 18.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: the odds. BMJ. 2000;320:1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Inder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbas Z, Hussain AS, Ibrahim F, Jafri SM, Shaikh H, Khan AH. Barrett's oesophagus and Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:331–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberg S, Peters JH, Nigro JJ, Theisen J, Hager JA, DeMeester SR, et al. Helicobacter pylori is not associated with the manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg. 1999;134:722–726. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sekiguchi T, Shirota T, Horikoshi T. Helicobacter pylori infection and severity of reflux. Gastroenterology 1996:A755. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Macchiarelli R, Marzocca F, De Giorgio F, Tedone F, Bayeli PF. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Int. 1998;11:194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velanovich V. The spectrum of Helicobacter pylori in upper gastrointestinal disease. Am Surg. 1995;62:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yerra LN, Bhasin DK, Panigrahi D, Vaiphei K, Sharma BC, Ray P. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:175–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connor HJ, Cunnane K. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—a prospective study. Ir J Med Sci. 1994;163:369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF02942830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Festen HPM, Lamers BHW, Jansen JBMJ, Snel P, et al. Long-term omeprazole therapy does not affect Helicobacter pylori status in most patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:978–980. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho KY, Kang JY. Reflux esophagitis patients in Singapore have motor and acid exposure abnormalities similar to patients in the western hemisphere. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1186–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bate CM, Tildesley G, Murray F, Dillon J, Crowe JP, Duggan SJ, et al. An effective omeprazole-based dyspepsia treatment protocol, based on clinical history, symptoms, and Helicobacter pylori status, that provides rapid symptom relief in the majority of patients. J Drug Assess. 1998;1:209–225. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berstad AE, Hatlebakk JG, Maartmann-Moe H, Berstad A, Brandtzag P. Helicobacter pylori gastritis and epithelial cell proliferation in patients with reflux oesophagitis after treatment with lansoprazole. Gut. 1997;41:740–747. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper BT, Gearty JC. Helicobacter pylori in Barrett's oesophagus. Gullet. 1991;1:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warburton-Timms VJ, Charlett A, Valori RM, Uff JS, Shepherd NA, Barr H, et al. The significance of cagA+ Helicobacter pylori in reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 2001;49:341–346. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3468–3472. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Kato K, Shimosegawa T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–334. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csendes A, Smok G, Cerda G, Burdiles P, Mazza D, Csendes P. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in 190 control subjects and in 236 patients with gastroesophageal reflux, erosive esophagitis or Barrett's esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10:38–42. doi: 10.1093/dote/10.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A, Jamal MM, Inadomi JM, Crooks LA, Feddersen RM. Corpus gastritis is protective against reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1999;45:181–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fallone CA, Barkun AN, Gottke MU, Best LM, Loo VG, van Zanten SV, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori genotype with gastroesophageal reflux disease and other upper gastrointestinal diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:659–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gisbert JP, de Pedro A, Losa C, Barreiro A, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: lack of influence of infection on twenty-four-hour esophageal pH monitoring and endoscopic findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:210–214. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldblum JR, Vicari JJ, Falk GW, Rice TW, Peek RM, Easley K, et al. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia: the role of gastroesophageal reflux and H. pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hackelsberger A, Schultze V, Gunther T, von Arnim U, Manes G, Malfertheiner P. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in patients with reflux oesophagitis: a case-control study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:465–468. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199806000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haruma K, Hamada H, Mihara M, Kamada T, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, et al. Negative association between Helicobacter pylori infection and reflux esophagitis in older patients: case-control study in Japan. Helicobacter. 2000;5:24–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liston R, Pitt MA, Banerjee AK. Reflux oesophagitis and Helicobacter pylori infection in elderly patients. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:221–223. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.846.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manes G, Mosca S, Laccetti M, Lioniello M, Balzano A. Helicobacter pylori infection, pattern of gastritis, and symptoms in erosive and nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:658–662. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mihara M, Haruma K, Kamada T, Kiyohira K, Goto T, Sumii M, et al. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1996;39(suppl 2):A94. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newton M, Bryan R, Burnham WR, Kamm MA. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori in reflux oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 1997;40:9–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pieramico O, Zanetti MV. Relationship between intestinal metaplasia of the gastro-oesophageal junction, Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:567–572. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schubert TT, Schnell GA. Prevalence of Campylobacter pylori in patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:637–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shirota T, Kusano M, Kawamura O, Horikoshi T, Mori M, Sekiguchi T. Helicobacter pylori infection correlates with severity of reflux esophagitis: with manometry findings. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s005350050372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaezi MF, Falk GW, Peek RM, Vicari JJ, Goldblum JR, Perez-Perez GI, et al. CagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori may protect against Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2206–2211. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varanasi RV, Fantry GT, Wilson KT. Decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Helicobacter. 1998;3:188–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, Easley KA, Schnell J, et al. The seroprevalence of cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu JC, Sung JJ, Ng EK, Go MYY, Chan WB, Chan FKL, et al. Prevalence and distribution of Helicobacter pylori in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study from the East. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1790–1794. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson SG. Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. In: Chalmers I, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, Festen HP, Liedman B, et al. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1018–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604183341603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.