Abstract

Heat-shock genes have numerous features that ought to predispose them to insertional mutagenesis via transposition. To elucidate the evolvability of heat-shock genes via transposition, we have exploited a local transposition technique and Drosophila melanogaster strains with EPgy2 insertions near the Hsp70 gene cluster at 87A7 to produce numerous novel EPgy2 insertions into these Hsp70 genes. More than 50% of 45 independent insertions were made into two adjacent nucleotides in the proximal promoter at positions −96 and −97, and no insertions were into a coding or 3′-flanking sequence. All inserted transposons were in inverse orientation to the starting transposon. The frequent insertion into nucleotides −96 and −97 is consistent with the DNase hypersensitivity, absence of nucleosomes, flanking GAGA-factor-binding sites, and nucleotide sequence of this region. These experimental insertions recapitulated many of the phenotypes of natural transposition into Hsp70: reduced mRNA expression, less Hsp70 protein, and decreased inducible thermotolerance. The results suggest that the distinctive features of heat-shock promoters, which underlie the massive and rapid expression of heat-shock genes upon heat shock, also are a source of evolutionary variation on which natural selection can act.

MOBILIZATION of DNA is a principal source of genetic and genomic variation (Kazazian 2004). Except for a few examples, accumulation of mobile elements accounts for 22 and 50% of the Drosophila and human genomes, respectively (Kapitonov and Jurka 2003; Bellen et al. 2004), and the proliferation of one class of mobile elements is proposed to account for the extraordinary gene duplication that accompanied the divergence of humans from sister groups (Bailey et al. 2003). Mobilization of DNA, moreover, is not solely a past event, but is ongoing in natural populations, where it may underlie evolutionary adaptation. In Drosophila, for example, the insertion of transposable elements into proximal promoters of heat-shock and cytochrome P450 genes, which thereafter segregate as alleles in natural populations, underlies adaptation to temperature and insecticides, respectively (Michalak et al. 2001; Bettencourt et al. 2002; Daborn et al. 2002; McCollum et al. 2002; Lerman et al. 2003; Petrov et al. 2003; Schlenke and Begun 2004; Aminetzach et al. 2005; Bogwitz et al. 2005; Lerman and Feder 2005; Marsano et al. 2005). Importantly, transposition into genes is not random, but requires insertion sites that are physically accessible to the transposition machinery, and all genes (or regions of genes) are not equal in providing access (Bellen et al. 2004). Presently, however, the exact basis for transposition into specific nucleotides and the avoidance of others is unknown (Bellen et al. 2004), and understanding this basis would enable prediction of the evolvability of specific sites via transposition.

To address this issue, we have exploited a variant of local transposition, which Timakov et al. (2002) have used to mutagenize specific regions of the Drosophila genome. Its principle is that P elements insert preferentially in genes near the starting site, and hence judicious choice of a starting P element can yield numerous transpositions into a target gene (if, that is, the target is susceptible to transposon insertion). As a primary target, we have selected the Hsp70 gene cluster at 87A7. The BDGP Gene Disruption Project (Bellen et al. 2004) has now yielded strains with ideal starting transposons distributed throughout the euchromatin, and we have selected two strains with EP transposons in neighboring genes of the target.

The 87A7 Hsp70 cluster contains two (Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab) of the five to six nearly identical genes that encode Hsp70, the principal heat-inducible molecular chaperone in Drosophila melanogaster (Bettencourt and Feder 2002). Several features of the cluster and its genes may predispose it to transpositional mutagenesis. The region upstream of the Hsp70 TATA element contains multiple binding sites for the sequence-specific regulatory proteins, GAGA factor (GAF) and heat-shock factor (HSF). Prior to heat shock, GAF resides on the Hsp70 promoter (Gilmour et al. 1989; O'Brien et al. 1995). The binding of GAF appears to maintain the promoter region in a nucleosome-free conformation (Karpov et al. 1984; Udvardy et al. 1985; Nacheva et al. 1989; Becker and Craig 1994; Tsukiyama et al. 1994; Georgel 2005), as is consistent with the DNase hypersensitivity of the region (Weber et al. 1997). The polymerase apparatus is preassembled but stalled, awaiting the arrival of activated HSF. Thus, the Hsp70 promoter is “bookmarked” (Xing et al. 2005). These features are thought to allow ready access of the general transcription factors to the core promoter and thus facilitate rapid induction of transcription upon heat shock, but may thereby facilitate the access of the transposition machinery to the underlying DNA, especially at or near the DNase hypersensitive sites. Finally, although nominally a heat-shock gene, Hsp70 is transcribed in the male germline (Boutanaev et al. 2002; Lakhotia and Prasanth 2002), which should to facilitate germline transposition. Indeed, numerous transposons have naturally and independently inserted into the Hsp70 proximal promoter (Michalak et al. 2001; Zatsepina et al. 2001; Bettencourt et al. 2002; Lerman et al. 2003; Lerman and Feder 2005; our unpublished data).

Insertional mutagenesis can have a dramatic impact on gene expression by adding novel regulatory elements to a gene or by disrupting preexisting regulatory regions (Kazazian 2004; Puig et al. 2004; Lerman and Feder 2005). In Hsp70, four heat-shock elements (HSEs) bind activated HSF; their number and spacing is crucial for full-strength gene expression (O'Brien and Lis 1991; Lis and Wu 1993; Amin et al. 1994; Li et al. 1996; Mason and Lis 1997; Weber et al. 1997). In natural populations, insertion of transposons into the Hsp70 promoter disrupts this spacing and thereby reduces Hsp70 expression (Lerman et al. 2003; Lerman and Feder 2005). This impact is due solely to the physical disruption of the promoter and not to transposition of regulatory elements, as replacement of the transposons with random DNA sequences of identical size has the same phenotype (Lerman and Feder 2005). In turn, reduced Hsp70 transcription can result in reduced (or, paradoxically, increased) Hsp70 protein, which affects inducible thermotolerance, growth, and development (Lerman et al. 2003). Thus, experimental mutagenesis of Hsp70 via local transposition may illustrate molecular and organismal phenotypes as well as the details of target sites.

Here we report outcomes of a local transposition experiment in which a mobilized transposon has inserted into one or both of the Hsp70 genes at 87A7 in 45 independent trials. Remarkably, >50% of these insertions were into two adjacent nucleotides in the proximal promoter at positions −96 and −97, and no insertions were into a coding or 3′-flanking sequence. DNase hypersensitivity, absence of nucleosomes, flanking GAGA-factor-binding sites, and preferred nucleotide sequence all coincide at −96 and −97. These experimental insertions, moreover, recapitulated many of the phenotypes of natural transposition into Hsp70, further supporting the hypothesis that heat-shock genes are exceptionally prone to evolution via transposition (Lerman et al. 2003; Lerman and Feder 2005).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains:

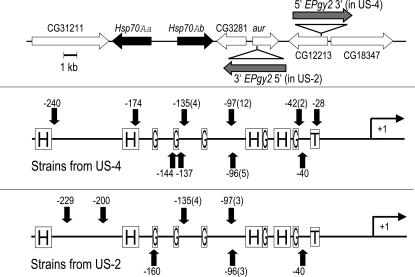

All flies were reared on a yeast, cornmeal, molasses, and agar medium at 25°. A transposase source stock (w[*]; ry[506] Sb[1] P{ry[+t7.2] = Delta2-3}99B/TM6B, Tb[1]), hereafter “Delta2-3,” and two stocks with insertions near the 87A7 Hsp70 gene cluster were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. The first insertion stock (stock no. 15616), hereafter named “US-4,” had the following genotype: y[1] w[67c23]; P{w[+mC] y[+mDint2] = EPgy2} EY03020; the second stock, hereafter named “US-2” (stock no. 15904), had the following genotype: y[1] w[67c23]; P{w[+mC] y[+mDint2] = EPgy2} EY03490. US-4 contains an EPgy2 insertion at +243 nucleotides relative to the transcription start of gene CG12213, and US-2 contains the same element at +33 nucleotides relative to the transcription start of aurora (aur). Figure 1 depicts the orientations of these insertions and of the host and Hsp70A genes. The insertion in US-4 is located ∼8 kb from the 5′-end of Hsp70Ab, and that in US-2 is located ∼5 kb from the 5′-end of Hsp70Ab.

Figure 1.

Starting and insertion sites for local transposition. (Top) Region 87A of chromosome 3, indicating position and orientation of the two Hsp70 genes in this region and adjacent genes, as well as approximate starting positions and orientations of the EPgy2 transposons to be mobilized. (Middle) For Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab combined, insertion sites of the EPgy2 transposon originally located in CG12213 (US-4 strain). Numbers before parentheses refer to nucleotide position relative to transcription start; numbers of independent transpositions into the indicated nucleotide are in parentheses. Two additional insertions were detectable but could not be localized. Approximate positions of heat-shock (H) and GAGA (G) elements and the TATA box are indicated. Of these 29 transpositions, 87% were into Hsp70Aa, and all were in an orientation opposite to that of the starting transposon. (Bottom) For Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab combined, insertion sites of the EPgy2 transposon originally located in aur (US-2 strain). Data are plotted as in the middle. Of these 14 transpositions, 57% were into Hsp70Aa, and all were in an orientation opposite to that of the starting transposon.

Genetic screen to detect local insertions:

Our isolation of local reinsertions of the EPgy2 element followed the approach of Golic (1994) and Timakov et al. (2002). This approach rests on two assumptions: that the starting element used to produce local insertions is retained in local transposition and that the expression of the marker (white) gene in the P-element construct would identify flies with additional insertions by darker eye pigmentation. For phenotype studies, selected strains carrying one or two insertions in the Hsp70A genes were made homozygous by individual crossings of flies with darker eyes. These crosses yielded the following homozygous (nonsegregating) strains: 1IIa, 5IId, 30IIb, 111IIa, 123Ia, 134Ib, 186Ib, 246I, 253Ia, 310II, 332II, 369I, and α34I (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Strains harboring local transpositions into Hsp70Aa, Hsp70Ab, and neighboring genes

| Strains derived from US-4 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain: | 1IIa | 2Ia | 5IId | 30IIb | 31IIa | 48Ia | 60IIaa | 61Ib | 86I | 99IIa | |

| 2-5 primers | 402 | 402 | 401 | 440 | 401 | 1.2 kb | 401 | 402 | |||

| 2-7 primers | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 2-6 primers | + | ||||||||||

| Localization | −97 | Not P | −97 | −96 | −135 | −96 | −240 | −96 | −97 | Not P | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa Ab | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | |||

| Strain: | 105Ig | 111IIa | 121II | 123Ia | 134Ib | 163Ia | 169Ig | 177I | 179I | 184I | |

| 2-5 primers | 401 | 402 | 2.6 kb | 440 | 332 | 402 | 402 | 401 | 402 | 1.6 kb | |

| 2-7 primers | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 2-6 primers | |||||||||||

| Localization | −96 | −97 | Not detected | −135 | −28 | −97 | −97 | −96 | −97 | Not detected | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | |

| Strain: | 186Ib | 244Ia | 246I | 253Ia | 253Ib | 258II | 284Ia | 288Ia | 288Ib | 288Ic | |

| 2-5 primers | 346 | 440 | 402 | 402 | 440 | 402 | 344 | 344 | 344 | ||

| 2-7 primers | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2-6 primers | |||||||||||

| Localization | −42 | Not P | −135 | −97 | −97 | −135 | −97 | −40 | −40 | −40 | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | ||

| Strain: | 288Id | 288Ie | 288Ik | 295II | 309Ib | 310II | 332IIa | 332IIba | 369I | 377II | |

| 2-5 primers | 344 | 344 | 344 | 402 | 346 | 442 | 2kb | 2kb | 449 | 479 | |

| 2-7 primers | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| 2-6 primers | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Localization | −40 | −40 | −40 | −97 | −42 | −137 | −97 | −97 | −144 | −174 | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Ab | Ab | Ab | Ab | Aa | Ab | |

| Strains derived from US-2 | |||||||||||

| Strain: | α3II | α9Ib | α21Iba | α33Ib | α34I | α79Ia | α36I | α196Ia | α200I | α198I | |

| 2-5 primers | 402 | 726 | 505 | 402 | 401 | 440 | 440 | 401 | |||

| 2-7 primers | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| 2-6 primers | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Localization | Not P | −97 | −229 | −200 | −97 | −96 | +791 | −135 | −135 | −96 | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa | Ab | Ab | CG3281 | Aa | Ab | Ab | ||

| Strain: | α198I | α250Ia | α138IIa | 148IIa | α196II | α59Ib | α199II | α227I | α120I | α121I | |

| 2-5 primers | 465 | 440 | 402 | 401 | 344 | 440 | |||||

| 2-7 primers | + | + | |||||||||

| 2-6 primers | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Localization | −160 | −135 | −97 | −96 | −40 | +103 | +252 | −135 | Not P | Not P | |

| Gene | Aa | Aa | Aa | Aa | Ab | CG3281 | CG3281 | Ab | |||

“Localization” refers to the relative position of the insertion to the transcription start. “Not P” refers to the insertions of other unknown TEs. “+” indicates positive PCR with 2 – 6 or 2 – 7 primers. Insertion in α 36I was detected with primers 3 and 6 and in α 59Ib and α199II with primers 6 and 7. The total number of DNAs isolated from the nonsegregating strains using the first construct (US-4) is 380. The total number of DNAs isolated from the nonsegregating strains using the second construct (US-2) is 100.

Long fragments with part of CG12213 or aur.

DNA manipulations and Southern analysis:

Isolation of genomic DNA from adult flies and Southern blot analysis to detect new insertions in Hsp70 genes was performed according to Evgen'ev et al. (2004). Five micrograms of each DNA sample was digested with HindIII and BamHI restriction endonucleases. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the gel was treated for 15 min in 0.25 m HCl and then incubated twice in denaturing buffer (1.5 m NaCl/0.5 m NaOH) for 30 min. After a 30-min incubation in neutralization buffer, gels were capillary blotted onto nylon membranes and fixed by UV crosslinking using the UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) protocol. Standard high-stringency hybridization and wash conditions were used for Southern blot analysis. To detect the positions of Hsp70 sequences in Southern blots, fragments of cloned D. melanogaster Hsp70 genes were labeled by random priming and used as probes. The original screen of Southern blots was with 5′-specific and 3′-specific probes prepared from the ClaI–SalI fragment of D. melanogaster Hsp70 (McGarry and Lindquist 1985), where the 5′-specific probe is the ClaI–BamHI fraction and the 3′-specific probe is the BamHI–SalI fraction.

Detection of local insertions with PCR:

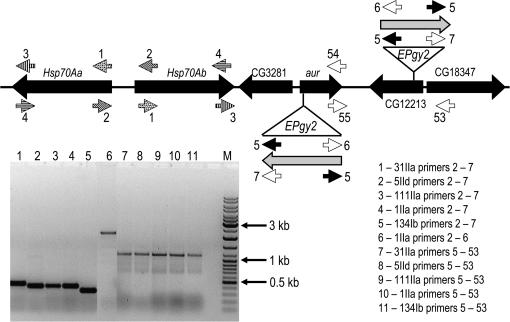

Drosophila genomic DNA was isolated as described (Evgen'ev et al. 2004). Each polymerase chain reaction consisted of 1.25 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) per probe, 0.1 μg DNA in 30 μl of buffer (Promega), 1.5–2 μm MgCl2, 0.2 mm of each dNTP, and 5 pm of each primer. Reaction conditions for all PCR reactions included 1.5 min at 94°; 30 cycles of 94° for 1 min, 56°–64° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min; and 72° for 5 min in a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA). Primers were complementary to the EPgy2 construct (Timakov et al. 2002), Hsp70A (GenBank accession no. AE003693), and adjacent genes. Figure 2 indicates their position and Table 2 their sequence.

Figure 2.

Determination of location and orientation of EPgy2 constructs via the polymerase chain reaction. (Top) Sites complementary to PCR primers described in materials and methods. (Bottom) Amplicon size, indicating differing sites of EPgy2 transposition into Hsp70Aa (lanes 1–5) and the unchanged location of the starting transposon (lanes 7–11) in the specified lines.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for this work

| Primer | Sequence | Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-ATGCCTGCTATTGGAATCGATC-3′ | 5′ Hsp70 inward |

| 2 | 5′-GATCGATTCCAATAGCAGGCAT-3′ | 5′ Hsp70 outward |

| 3 | 5′-GAGGAGTTCGACCACAAGC-3′ | 3′ Hsp70 outward |

| 4 | 5′-GCTTGTGGTCGAACTCCTC-3′ | 3′ Hsp70 inward |

| 5 | 5′-CGACGGGACCACCTTATGTTA-3′ | Invert repeat of P element |

| 6 | 5′-AATTCGTCCGCACACAAC-3′ | 5′ P element outward |

| 7 | 5′-ATCATATCGCTGTCTCACTCAG-3′ | 3′ P element outward |

| 53 | 5′-TACACGAAGGTGCAAATCG-3′ | To CG18347 |

| 54 | 5′-GTCCCGAATTAGCAGTAATC-3′ | To 3′ of aur inward |

| 55 | 5′-GATTACTGCTAATTCGGGAC-3′ | To 3′ of aur outward |

| Hsp70A-1 | 5′-CCTGGAGAGCTACGTCTTCAAT-3′ | Used in Q-RT–PCR |

| Hsp70A-2 | 5′-GTCGTTGCACTTGTCCAA-3′ | Used in Q-RT–PCR |

| rp49-1 | 5′-CGCACCAAGCACTTCATCC-3′ | Used in Q-RT–PCR |

| rp49-2 | 5′-AGCGGCGACGCACTCTGT-3′ | Used in Q-RT–PCR |

See also Figure 2.

Sequencing:

Sequences flanking EPgy2 insertions were obtained via PCR with a genomic primer (2, 53, 54, or 55, Table 2) and a primer specific to the 5′-end or 3′-end of EPgy2. The PCR product was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel in TAE, and the band containing the amplified DNA was excised and purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA) for subsequent sequencing with one of the primers used in the PCR reaction. The PCR fragments were sequenced. Sequencing was with Sequenase (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and ABI 377 sequencers. In some cases internal sequencing primers were used to provide double-strand coverage. Sequences were assembled manually and aligned using CLUSTAL X (Jeanmougin et al. 1998).

Quantitative RT–PCR:

Equal amounts (1 μg) of RNA were used to synthesize first-strand cDNA with oligo(dT) in the reverse transcription reaction [Abgene (Rochester, NY) first-strand synthesis kit] according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hsp70A mRNA was determined by real-time quantitative PCR with an MJ Opticon detector, SYBR green detection method, and ABgene reagents. The housekeeping gene rp49 was used as a loading control. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The copy numbers of RNA encoded by the Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab genes, collectively, were standardized against rp49 mRNA in each sample. The PCR reaction used primers (Table 2) complementary to both Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab but not to the Hsp70 genes at 87C1. Specificity was established in preliminary experiments with the Hsp70A and Hsp70B deletion strains (Gong and Golic 2004) (data not shown).

Thermotolerance studies:

Procedures were identical to those of Garbuz et al. (2002). Eclosing individuals were sequestered daily and, when 4 days old, were transferred by aspiration to a preheated polypropylene vial, which was immersed in a thermostated water bath for 30 min. Each vial usually contained 75–100 animals. To determine basal thermotolerance, vials were placed at one of a series of temperatures ranging from 38.5° to 40°. To determine inducible thermotolerance, similar determinations ensued after flies first underwent pretreatment at 35° for 30 min and 25° for 1 hr. Tolerance was assessed as the proportion of flies that could walk 48 hr after heat shock.

Immunoblotting:

Procedures were identical to those of Garbuz et al. (2002). In brief, lysates were prepared from 4-day-old flies after heat shock at various temperatures. After sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of 10 μg total protein per lane, the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL; Amersham) according the manufacturer's protocol. Monoclonal antibody specific to D. melanogaster Hsp70 (7FB) was obtained from Susan Lindquist (University of Chicago). Immune complexes were detected via chemoluminescence (ECL kit, Amersham) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis) with appropriate peroxidase-conjugated anti-rat secondary antibodies.

Preparation of RNA and Northern hybridization:

Procedures were identical to those of Garbuz et al. (2003). RNA from adult flies was prepared by the standard method with guanidine isothiocyanate, separated by gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane for hybridization with the ClaI–BamHI fragment of the D. melanogaster Hsp70 gene (McGarry and Lindquist 1985). Hybridization was overnight at 42° in 50% formamide, followed by two 20-min washes in 2× SSC, 0.2% SDS at 42°, and one 20-min wash in 0.2× SSC, 0.2% SDS at 68°.

RESULTS

Producing local insertions in the 87A region of chromosome 3:

The EPgy2 construct contains mini-white, whose phenotype is a light-orange eye color, as a marker. In progeny of crosses of Delta2-3 with flies bearing this construct in either of the starting locations, the element was frequently excised, as was evident from patches of white cells (mosaics) on a background of cells with light-orange pigmentation (data not shown).

Females of both stocks with starting elements were crossed en masse to Delta2-3 males and resulting F0 males were crossed singly to yw/yw females (Df1 strain). F1 males exhibiting darker eye color (dark orange or light red) in comparison with other males were crossed with yw/yw females individually and checked for segregation in the subsequent generations. In the F1 for US-4, 562 males of 7400 exhibited darker color. Therefore, frequency of transposition was ∼7.5%. In the US-2 series, 232 of 4725 F1 males carried new insertions; thus, total transposition frequency for this series was 4.9%. Segregating strains displaying various eye colors in the progeny of individual crosses of these males probably resulted from nonlocal transpositions and were not analyzed further.

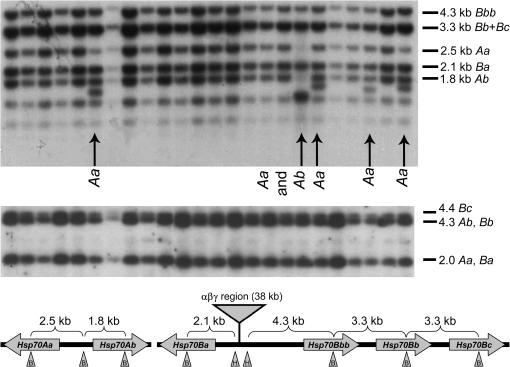

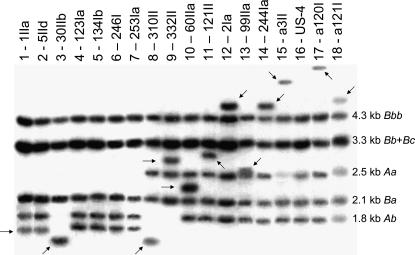

Strategy and proof of principle:

All nonsegregating F1 strains with dark eye color first underwent screening by Southern blot analysis to determine into which, if any, of the six Hsp70 genes EPgy2 had inserted. In this analysis, HindIII–BamHI restriction digests yield products readily assignable to each Hsp70 gene (Figure 3). Because the EPgy2 construct includes a HindIII site, the insertion of the element in the heterozygous condition should yield an additional band of lower molecular weight (Figure 3), while in homozygous condition it should eliminate the band corresponding to the Hsp70 gene(s) into which each insertion was made (Figure 4). The Southern blots were hybridized with either 5′- or 3′-specific Hsp70 probes to localize insertions within the Hsp70 genes. Hybridization with the 3′ probe detected no insertions of EPgy2 in the 3′-coding part of the gene or its flanking region. Reprobing of the same blots with the 5′ probe, by contrast, detected numerous heterozygous insertions in this region (Figure 3). Crosses of these strains yielded homozygous strains (Figure 4) in many but not in all cases, probably because the insertions were sometimes associated with lethality or sterility. The specific site of insertion was determined by PCR and subsequent sequence analysis (see below). Several insertions (three for US-4 and three for US-2) in Hsp70 genes apparently did not contain the EPgy2 construct (Figure 4). The high molecular weight bands in lanes 12–15 and 17–18 (strains 2Ia, 99IIa, 244Ia, α3II, α120I, and α121I, Figure 4) may be due to mutations in the restriction site and/or inserting element or to the insertion of mobile elements other than the EPgy2 construct (see Lewis and Brookfield 1987).

Figure 3.

Representative genomic Southern blot used to screen nonsegregating lines for transposition into Hsp70 genes: lines heterozygous for insertions. (Top) Hybridization with the ClaI–BamHI fragment of Hsp70, which is specific for the 5′ region of Hsp70 genes. BamHI–HindIII digestion yields fragments of indicated sizes. As indicated by arrows, in strains heterozygous for EPgy2 elements in Hsp70 genes, a HindIII site in EPgy2 reduces the concentration of the band corresponding to the corresponding gene and results in a band of lower molecular weight. (Middle) Hybridization with the BamHI–SalI fragment of Hsp70, which is specific for the 3′ region of Hsp70 genes. BamHI–HindIII digestion yields fragments of indicated sizes. As indicated by the absence of variation from canonical fragment size, no EPgy2 elements inserted into the 3′ portion of Hsp70 genes. (Bottom) Organization of the Drosophila Hsp70 genes in the experimental lines (Gong and Golic 2004), indicating the BamHI–HindIII restriction sites (B and H in triangles, respectively) and origin of the corresponding fragments in the top of the figure. The first two genes are at 87A7, and the last four genes are at 87C1. Not to scale.

Figure 4.

Representative genomic Southern blot used to screen nonsegregating lines for transposition into Hsp70 genes: lines homozygous for insertions and unusual mutants. Lanes 1–8: insertions of the EPgy2 element only; see Table 1 for specific insertion sites. Lane 16: a strain with the EPgy2 element in the starting position. Lane 9: 1.5 kb of GC12213 flanking sequence has been cointegrated with the P-construct. Lane 10: 1 kb of GC12213 flanking sequence has been cointegrated with the P-construct. Lane 11: ∼2.3 kb of GC12213 flanking sequence has been cointegrated with the P-construct. Lanes 12–15, 17, and 18: instances of aberrant Southern analyses but with no EPgy2 insertion into the Hsp70A locus detectable by PCR. These may be due either to aberrations or to insertions of unidentified transposons.

Localization of insertions in Hsp70 genes:

Southern blot analysis (e.g., Figures 3 and 4) of the Hsp70Aa-Hsp70Ab gene cluster at 87A7 detected 31 independent insertions of the EPgy2 construct from US-4 and 14 insertions from US-2 among 375 and 160 nonsegregating strains, respectively. Hybridization with Hsp70 5′-specific and 3′-specific probes revealed that all of the insertions were into the 5′ regions of Hsp70 genes. A combination of PCR and sequencing resolved the specific insertion sites (Table 1; Figures 1 and 2). Remarkably, 55% of the US-4 insertions and 40% of the US-2 insertions were into the same two nucleotides in the Hsp70A promoters, positions −96 and −97. Each insertion was a singleton except for cross 30IIb (derived from US-4) and cross α198I (derived from US-2), in which both Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab received insertions. In two cases (288Ia-k and 332II-332IIb) insertions in the progeny of US-4 strain F1 males were identical, consistent with premeiotic transposition.

In ∼300 strains with insertions outside of Hsp70A, insertions were mapped to specific genes with the 53-5, 54-5, 55-5, and 3-5 primer pairs (Table 2). Of these, 4% were in aurora, CG18374, and CG3281, genes near Hsp70A (Figure 2). In contrast to the insertions in Hsp70A, the insertions in these genes were not concentrated in promoter regions but were randomly distributed along the genes' length.

The orientation of the local insertions relative to the starting element was determined with primers specific for the putative host gene and primers complementary to the P-element-containing construct. All insertions into Hsp70A were oriented opposite to the starting element (Figure 1), implying that constructs always underwent a 180° rotation during insertion.

Interestingly, in crosses involving the US-4 strain, most (87%) insertions were into Hsp70Aa, the gene more distal from the starting position. By contrast, in the crosses involving US-2, insertions were more evenly distributed (57% in Hsp70Aa and 43% in Hsp70Ab).

Because of the extraordinary conservation of Hsp70 coding sequence, the same primers used to detect transposition into the 87A7 Hsp70 cluster were sufficient to detect transposition into the 87C1 Hsp70 cluster, as were the Southern blots. Neither screen detected any transposition into the 87C1 cluster, which is much more distant from the starting transposons than is 87A7.

Gene expression and protein levels:

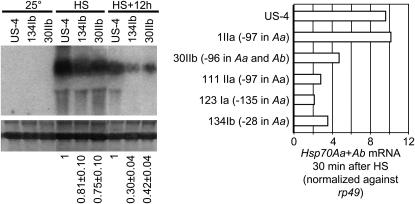

Gene-cluster-specific quantitative RT–PCR (Q-RT–PCR) primers enabled distinction of Hsp70A-specific mRNA from total Hsp70 mRNA. In four of five cases, local transposition into the Hsp70A gene cluster reduced Hsp70A mRNA present after a 37.5° heat shock for 30 min (Figure 5). The reduction was similar for insertions at −135, −97 (strain 111IIa), and −28 in Hsp70Aa and at −96 in both Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab and was 20–40% of levels in the US-4 strain from which these strains were derived (Figure 5, left). In the pair of these strains examined after a 37° heat shock for 30 min, total Hsp70 mRNA (i.e., Hsp70A mRNA + Hsp70B mRNA) was 75–80% of levels in the US-4 strain. Twelve hours after heat shock, total Hsp70 mRNA was 30–40% of levels in the US-4 strain.

Figure 5.

Local transposition into Hsp70A promoters affects total Hsp70 mRNA, but not consistently. (Left) Total mRNA from all six Hsp70 genes. Heat shock was 37° for 30 min. Within each treatment, mRNA abundance in a strain with transposition into Hsp70Aa (134Ib) or into both Hsp70A genes (30IIb) was compared to that for controls (US-4 strain) via densitometry; mean ± standard error of relative abundance is indicated below the corresponding lane. (Right) Sum of Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab mRNA. The mRNA abundance in strains with one to two transpositions into Hsp70A was compared to that for controls (US-4 strain) via quantitative RT–PCR and normalized against rp49 mRNA; means of three replicate determinations.

By contrast, in an independently derived strain with a transposon insert at −97 in Hsp70Aa (strain 1IIa), Hsp70A mRNA was the same as in the US-4 strain from which it was derived (Figure 5, left). A second determination of Hsp70A mRNA confirmed this outcome, after which the presence of the transposon at −97 was reverified by PCR and Southern hybridization.

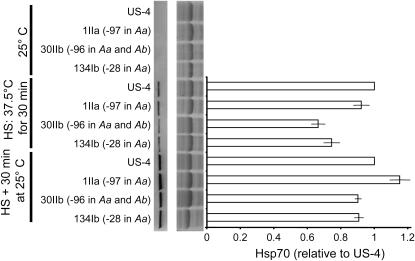

Total Hsp70 protein levels approximately corresponded to these findings (Figure 6). In the 1IIa and US-4 strains, Hsp70 protein was similar in abundance after a 37° heat shock for 30 min. In two strains in which Hsp70A mRNA was reduced, Hsp70 protein was also reduced. By 30 min after heat shock, however, the difference in Hsp70 levels between these strains and US-4 had decreased. These strains exhibited similar levels of another Hsp70 family member, Hsp68, after heat shock according to 2-D PAGE (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Hsp70 protein in strains with transposition into Hsp70A and into a control strain (US-4). Images (rotated 90°) are a total Hsp70 immunoblot with antibody 7FB (left) and the corresponding Coomassie-stained membrane. (Right) Hsp70 abundance compared to that for controls (US-4 strain) via densitometry; mean ± standard error of relative abundance in four independent experiments is indicated.

Thermotolerance:

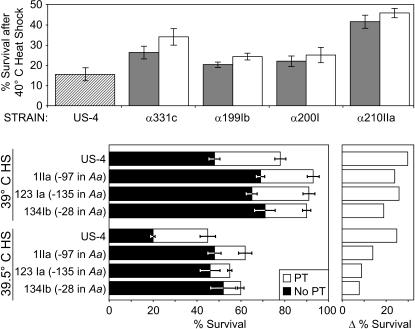

As discussed above, genesis of the Hsp70 transposon lines involved crossing two parental strains and mobilization of the original transposon. Both procedures and differing genetic backgrounds may affect thermotolerance, as is evident in four arbitrarily chosen pairs of strains derived from separate US-4 crosses. In all pairs, basal thermotolerance was greater than in US-4 (Figure 7). In each pair, one strain had lost the original EPgy2 transposon (detectable by white eye color) and the other included an EPgy2 transposon that had inserted outside the Hsp70 genes and proximal flanking sequence. In each case, the transposon insertion strain had greater basal thermotolerance than its transposon-less counterpart. Likewise, all tested strains with insertions into Hsp70A had greater basal thermotolerance than their parental strain (Figure 7 and strains 111IIa, 30IIb, and 310II; data not shown). These differences are obviously not attributable to Hsp70, especially because Hsp70 is typically undetectable before heat shock (Velazquez et al. 1983). By contrast, when US-4 and three Hsp70 transposon strains derived from it underwent heat pretreatment before heat shock, the improvement in thermotolerance was greater in US-4 than in the Hsp70 transposon-bearing strains. This difference was not evident for heat shocks of 40° or greater, at which survival was <20% (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Local transposition into the Hsp70A promoter decreases inducible but not basal thermotolerance. (Top) Effect on basal thermotolerance in four pairs of strains and in the strain from which these were derived (US-4). Each pair of lines was founded from segregants (recognizable by eye color) from an independent cross of US-4 with Delta2-3, one (shaded bar) carrying a novel insertion not in Hsp70 and one (open bar) from which the EPgy2 element had been lost. All pairs had greater thermotolerance than did US-4. (Bottom) Thermotolerance in strains with transposition into Hsp70Aa and in the strain from which they were derived (US-4). Plotted are means for flies with (open bars) or without (solid bars) pretreatment (35° for 30 min) before heat shock. The difference of means with and without thermotolerance is replotted at the right.

DISCUSSION

Transposition:

Local transposition is an effective means of generating mutations in a target gene (Timakov et al. 2002) and has been a key component of the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project (Bellen et al. 2004). Here we show that the technique of Timakov et al. (2002) can be used to define insertion site preference at the level of the individual nucleotide.

As has long been known, P elements do not insert at random in transposition experiments or screens, but preferentially into the 5′-flanking region of coding sequence (Spradling et al. 1995). Furthermore, in addition to this general preference are hotspots for P insertion, either into specific genes or regions of genes. The exact basis for this behavior is presently unknown, but “presumably” involves some combination of favorable chromatin accessibility, DNA target sequence, bound proteins, and relationship to the transposon's starting site (Bellen et al. 2004). These features are consistent with several correlates of transposition frequency, including the transcriptional activity of the target gene and DNase hypersensitivity (Voelker et al. 1990). The primary DNA sequence of the target site (as opposed to its accessibility and physical structure) seems a relatively unimportant determinant of transposition frequency (Liao et al. 2000). In conclusion, the lack of exactitude in this summary should be evident.

Remarkably, more than half of the local transpositions into Hsp70—23 in total—are into one of the same two nucleotides (−96 and −97) in the Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab genes. Independent repeated transposition into specific nucleotides is not unprecedented (Tower et al. 1993). The most spectacular example, however, is for CG9894, which received >700 independent hits in the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project, most of which were at specific nucleotides (Bellen et al. 2004; Figure 4). As Bellen et al. (2004, p. 778) state, “it may be possible to use insertion preferences as tools to probe chromosome organization and function.” Indeed, the insertions into −96 and −97 in the Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab genes implicate several specific mechanisms.

First, the regions are in the 5′-flanking regions of heat-shock genes (Spradling et al. 1995). In this study, transposition into either the coding or 3′-flanking sequences of Hsp70Aa and Hsp70Ab never occurred, despite their sometimes-greater proximity to the starting transposon. This outcome contrasts to that for neighboring genes. As a class, heat-shock genes exhibit several distinctive features (see Introduction), of which many maintain these genes' proximal promoters in a decondensed, nucleosome-free architecture, which in principle should make the chromatin accessible to the transposition apparatus. Indeed, in the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project, “heat-shock genes” exceeded numerous other gene classes in their susceptibility to P-element insertion (Bellen et al. 2004). In addition, Hsp70 is expressed when germ cells develop (Boutanaev et al. 2002).

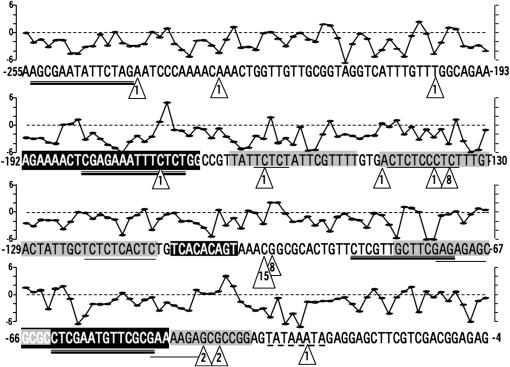

Second, the focal nucleotides, −96 and −97, are in a unique region of the Hsp70 promoter (Figure 8). The attractiveness of the Hsp promoter as a model of environmental control of gene expression has yielded numerous detailed studies of this promoter's architecture. In vivo, much of the proximal Hsp70 promoter is occupied by GAF, TATA box-binding factor, and their associated protein complexes (Farkas et al. 2000; Lebedeva et al. 2005). A given GAF, in addition to participating in the chromatin-remodeling complex, can interact with other GAFs to organize chromatin into nucleosome-like domains in which the chromatin wraps around the GAFs (Georgel 2005). These structures prospectively present a distinctive chromatin conformation to transposase complexes. Nucleotides −96 and −97 are in the middle of a window (from ∼−80 to −111) flanked by GAF-binding sites but unprotected by bound GAF (Gilmour et al. 1989; Weber et al. 1997; Georgel 2005). Other such windows exist, but none are so large. Indeed, positions −109 to −100 correspond to DH2, the most hypersensitive of the DNase hypersensitive sites in the proximal promoter of Hsp70 (Wu 1984; Weber et al. 1997).

Figure 8.

Annotation of the Hsp70 proximal promoter sequence, indicating locations of EPgy2 element insertions from this study (triangles indicating the number of independent insertions from both starting sites), HSEs (double underlining), GAGA-factor-binding sites (single underlining), regions protected by GAF (shading) (Gilmour et al. 1989), and DNase hypersensitive sites (black background with white text) (Weber et al. 1997). Above each nucleotide the corresponding score of the 14-bp window extending 3 bases upstream and 10 bases downstream is indicated, calculated from a position weight matrix (Sosinsky et al. 2003) derived from the training set of Julian (2003).

Finally, the sequence centered at −96 and −97 may favor transposition. O'Hare and Rubin (1983) reported a consensus sequence of GGCCAGAC, but with considerable variation from the consensus tolerated. Physical and bioinformatic analyses have implicated GC richness as contributing to insertion site preference, with six triplets (CAG, CTG, GAC, GCC, GGC, and GTC) and four dinucleotides (CC, GC, GG, and GT) often present. Fourteen base pairs (the 8-bp insertion site and 3 bp on either side) are a palindrome with a distinctive hydrogen bonding pattern (Liao et al. 2000). Recently Julian (2003) analyzed 795 P transpositions from the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project in detail and detected a preference for A/T at either end of the 14 bp. The insertion sites at −96 and −97 match Julian's consensus site at many positions, including the A/Ts in the specified positions. From Julian's (2003) training set, we have calculated a position weight matrix (Sosinsky et al. 2003) for this sequence and have scored a sliding window of 14 bp along the Hsp70 promoter. Many (but not all) of the transposon insertion sites, including −96 or −97, are at or within 3 bp of local maxima for the score.

This analysis clearly cannot explain every local transposition into Hsp70. A site of eight independent insertions, −135, is in a region normally protected by GAF binding, not particularly hypersensitive, and dissimilar to Julian's (2003) consensus site.

Our prior discoveries of naturally occurring transpositions into Hsp70 genes are entirely consistent with these patterns. To date, we have reported on three P and one Jockey element in the proximal promoters of the Hsp70B genes and on a degenerate transposon (“56H8”) and an HMS Beagle element in the region between the Hsp70A coding sequences (Michalak et al. 2001; Zatsepina et al. 2001; Bettencourt et al. 2002; Lerman et al. 2003; Lerman and Feder 2005). In this study, however, only Hsp70A, and not Hsp70B, was targeted by local transposition although the proximal promoters of Hsp70 genes in these two clusters are identical for much of their length. We suggest that the latter cluster was simply out of range of local transposition.

Phenotypes of insertion lines:

The Hsp70 promoter is sensitive to mutations in the number and spacing of HSEs. Accordingly, we have suggested that transposition into the Hsp70 promoter is a natural and normal source of evolutionary variation, which natural selection can fix or purge depending on the need for high levels of Hsp70 protein (Lerman et al. 2003). Tolerance of high temperatures is proportional to cellular Hsp70 levels, within limits (Krebs and Feder 1998). Hsp70 is a protein with numerous functions, however, many of which require stringent regulation of Hsp70 levels, and so high cellular concentrations of Hsp70 can be deleterious (Lerman et al. 2003). Depending on the frequency and severity of heat shock, high or low levels of Hsp70 may be beneficial to Drosophila (Lerman et al. 2003).

Consistent with this reasoning, natural populations of Drosophila harbor Hsp70 alleles with P elements (or other transposons) in their proximal promoters (Michalak et al. 2001; Zatsepina et al. 2001; Bettencourt et al. 2002; Lerman et al. 2003; Lerman and Feder 2005). These segregate as alleles in nature and are at high frequencies, which Petrov et al. (2003) and others have viewed as indicative of positive selection. The frequency of transposon-bearing alleles, moreover, varies along ecological gradients in a manner consistent with selection (Michalak et al. 2001; Bettencourt et al. 2002). Other heat-shock genes also harbor numerous transposons in their proximal promoters (Franchini et al. 2004; our unpublished data).

Although P elements in particular may initially have large (and negative) effects and lead to ongoing mutagenesis upon first invasion of a Drosophila genome, selection readily leads to suppression of P transposition, degradation of the elements themselves, or co-evolution of the host genes enabling function despite (or contingent on) the transposons (Pinsker et al. 2001). We know only that the naturally occurring P elements invaded the D. melanogaster genome 50–200 years ago (Pinsker et al. 2001), and not how their phenotypes have evolved since their insertion into Hsp70 promoters. The de novo insertions into the Hsp70A promoters provide an opportunity to recapitulate the original phenotypes of such elements. At the level of gene expression, the EPgy2 elements almost always reduced the expression of the host gene, consistent with the requirement of the wild-type promoter sequence for full-strength expression of Hsp70 genes (see above). The one exception, strain 1IIa, is enigmatic. An important nuance is that the D. melanogaster strains in this study have six nearly identical Hsp70 copies. Insertional mutagenesis of one to two Hsp70 copies might therefore have modest effects on total Hsp70 mRNA. Indeed, in the mutant lines total Hsp70 mRNA levels (Figure 4) and total Hsp70 protein levels (Figure 5) typically decreased 15–30% relative to controls after heat shock. Correspondingly, inducible thermotolerance was lower in controls (Figure 6). Previous work with natural and mutant lines has shown that such reductions are accompanied by increases in fitness components in the absence of stress (Lerman et al. 2003). This latter impact may account for the perpetuation of P elements in Hsp promoters in natural populations.

Finally, the Hsp70 transposon strains and others (Gong and Golic 2004) may provide a useful test bed for emerging models of the regulation of Hsp70 expression (Rieger et al. 2005). The six Hsp70 genes each include four HSEs in their proximal promoter, and heat-shock protein levels are predicted to be highly sensitive to concentrations of activated HSF (Sarge et al. 1993; Rieger et al. 2005) and its occupancy of HSEs. As discussed above, transposons in hsp promoters may reduce gene expression by disrupting the native promoter conformation and binding HSF. Paradoxically, however, transposons in specific Hsp70 genes may increase expression of nonaffected Hsp70 genes by increasing the amount of available HSF. Because the 87A7 and the 87C1 Hsp70 clusters show dramatically different kinetics and spatial patterns of expression (Lakhotia and Prasanth 2002), such redistribution of HSF might be highly consequential. This suggestion obviously awaits future examination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Zelentsova for performing in situ hybridization to confirm the localization of inserts, Ping Zhang for methodological advice, the Berkeley Drosophila Gene Disruption Project for producing the transposon source strains, Jean-Claude Walser for comments on the manuscript, and David S. Gilmour and Allan C. Spradling for detailed discussion of the Hsp70 promoter and transposition, respectively. Spradling suggested that disruption of one HSE might redistribute HSF to other HSEs. The work was supported by a Russian Academy grant for Molecular and Cellular Biology to M.B.E., Russian Grants for Basic Science 06-04-48993-a and 06-04-48854-a, and National Science Foundation grant IBN03-16627. Bing Chen was supported by the China Scholarship Council.

References

- Amin, J., M. Fernandez, J. Ananthan, J. T. Lis and R. Voellmy, 1994. Cooperative binding of heat shock transcription factor to the Hsp70 promoter in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 4804–4811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminetzach, Y. T., J. M. Macpherson and D. A. Petrov, 2005. Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila. Science 309: 764–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J. A., G. Liu and E. E. Eichler, 2003. An Alu transposition model for the origin and expansion of human segmental duplications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73: 823–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J., and E. A. Craig, 1994. Heat-shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Eur. J. Biochem. 219: 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen, H. J., R. W. Levis, G. C. Liao, Y. C. He, J. W. Carlson et al., 2004. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics 167: 761–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, B. R., and M. E. Feder, 2002. Rapid concerted evolution via gene conversion at the Drosophila Hsp70 genes. J. Mol. Evol. 54: 569–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, B. R., I. Kim, A. A. Hoffmann and M. E. Feder, 2002. Response to natural and laboratory selection at the Drosophila Hsp70 genes. Evolution 56: 1796–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogwitz, M. R., H. Chung, L. Magoc, S. Rigby, W. Wong et al., 2005. Cyp12a4 confers lufenuron resistance in a natural population of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 12807–12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutanaev, A. M., A. I. Kalmykova, Y. Y. Shevelyou and D. I. Nurminsky, 2002. Large clusters of co-expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. Nature 420: 666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daborn, P. J., J. L. Yen, M. R. Bogwitz, G. Le Goff, E. Feil et al., 2002. A single P450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science 297: 2253–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evgen'ev, M. B., O. G. Zatsepina, D. Garbuz, D. N. Lerman, V. Veleikodvorskaja et al., 2004. Evolution and arrangement of the hsp70 gene cluster in two closely-related species of the virilis group of Drosophila. Chromosoma 113: 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, G., B. A. Leibovitch and S. C. Elgin, 2000. Chromatin organization and transcriptional control of gene expression in Drosophila. Gene 253: 117–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini, L. F., E. W. Ganko and J. F. McDonald, 2004. Retrotransposon-gene associations are widespread among D. melanogaster populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 1323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbuz, D. G., V. B. Molodtsov, V. V. Velikodvorskaia, M. B. Evgen'ev and O. G. Zatsepina, 2002. Evolution of the response to heat shock in genus Drosophila. Russ. J. Genet. 38: 925–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbuz, D., M. B. Evgenev, M. E. Feder and O. G. Zatsepina, 2003. Evolution of thermotolerance and the heat-shock response: evidence from inter/intraspecific comparison and interspecific hybridization in the virilis species group of Drosophila. I. Thermal phenotype. J. Exp. Biol. 206: 2399–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgel, P. T., 2005. Chromatin potentiation of the Hsp70 promoter is linked to GAGA-factor recruitment. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83: 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, D. S., G. H. Thomas and S. C. Elgin, 1989. Drosophila nuclear proteins bind to regions of alternating C and T residues in gene promoters. Science 245: 1487–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golic, K. G., 1994. Local transposition of P elements in Drosophila melanogaster and recombination between duplicated elements using a site-specific recombinase. Genetics 137: 551–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W. J., and K. G. Golic, 2004. Genomic deletions of the Drosphila melanogaster Hsp70 genes. Genetics 168: 1467–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmougin, F., J. D. Thompson, M. Gouy, D. G. Higgins and T. J. Gibson, 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23: 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian, A. M., 2003. Use of bioinformatics to investigate and analyze transposable element insertions in the genomes of Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, and into the target plasmid pGDV1. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

- Kapitonov, V. V., and J. Jurka, 2003. Molecular paleontology of transposable elements in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 6569–6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpov, V. L., O. V. Preobrazhenskaya and A. D. Mirzabekov, 1984. Chromatin structure of Hsp70 genes, activated by heat shock: selective removal of histones from the coding region and their absence from the 5′ region. Cell 36: 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian, H. H., 2004. Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science 303: 1626–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, R. A., and M. E. Feder, 1998. Hsp70 and larval thermotolerance in Drosophila melanogaster: How much is enough and when is more too much? J. Insect Physiol. 44: 1091–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhotia, S. C., and K. V. Prasanth, 2002. Tissue- and development-specific induction and turnover of Hsp70 transcripts from loci 87A and 87C after heat shock and during recovery in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 205: 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva, L. A., E. N. Nabirochkina, M. M. Kurshakova, F. Robert, A. N. Krasnov et al., 2005. Occupancy of the Drosophila Hsp70 promoter by a subset of basal transcription factors diminishes upon transcriptional activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 18087–18092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, D. N., and M. E. Feder, 2005. Naturally occurring transposable elements disrupt Hsp70 promoter function in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22: 776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, D. N., P. Michalak, A. B. Helin, B. R. Bettencourt and M. E. Feder, 2003. Modification of heat-shock gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster populations via transposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A. P., and J. F. Y. Brookfield, 1987. Movement of Drosophila melanogaster transposable elements other than P elements in a P-M hybrid dysgenic cross. Mol. Gen. Genet. 208: 506–510. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., J. A. Weber, Y. Chen, A. L. Greenleaf and D. S. Gilmour, 1996. Analyses of promoter-proximal pausing by RNA polymerase II on the Hsp70 heat shock gene promoter in a Drosophila nuclear extract. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 5433–5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, G. C., E. J. Rehm and G. M. Rubin, 2000. Insertion site preferences of the P transposable element in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 3347–3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis, J., and C. Wu, 1993. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling, and trucking along. Cell 74: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsano, R. M., R. Caizzi, R. Moschetti and N. Junakovic, 2005. Evidence for a functional interaction between the Bari1 transposable element and the cytochrome P450 cyp12a4 gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Gene 357: 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. B., and J. T. Lis, 1997. Cooperative and competitive protein interactions at the Hsp70 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 33227–33233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum, A., E. Ganko, P. Barrass, J. Rodriguez and J. McDonald, 2002. Evidence for the adaptive significance of an LTR retrotransposon sequence in a Drosophila heterochromatic gene. BMC Evol. Biol. 19: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, T. J., and S. Lindquist, 1985. The preferential translation of Drosophila Hsp70 mRNA requires sequences in the untranslated leader. Cell 42: 903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak, P., I. Minkov, A. Helin, D. N. Lerman, B. R. Bettencourt et al., 2001. Genetic evidence for adaptation-driven incipient speciation of Drosophila melanogaster along a microclimatic contrast in “Evolution Canyon,” Israel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 13195–13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacheva, G. A., D. Y. Guschin, O. V. Preobrazhenskaya, V. L. Karpov, K. K. Ebralidse et al., 1989. Change in the pattern of histone binding to DNA upon transcriptional activation. Cell 58: 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, T., and J. T. Lis, 1991. RNA polymerase II pauses at the 5′ end of the transcriptionally induced Drosophila Hsp70 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11: 5285–5290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, T., R. C. Wilkins, C. Giardina and J. T. Lis, 1995. Distribution of GAGA protein on Drosophila genes in vivo. Genes Dev. 9: 1098–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare, K., and G. M. Rubin, 1983. Structures of P transposable elements and their sites of insertion and excision in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Cell 34: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, D. A., Y. T. Aminetzach, J. C. Davis, D. Bensasson and A. E. Hirsh, 2003. Size matters: non-LTR retrotransposable elements and ectopic recombination in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 880–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker, W., E. Haring, S. Hagemann and W. J. Miller, 2001. The evolutionary life history of P transposons: from horizontal invaders to domesticated neogenes. Chromosoma 110: 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig, M., M. Caceres and A. Ruiz, 2004. Silencing of a gene adjacent to the breakpoint of a widespread Drosophila inversion by a transposon-induced antisense RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 9013–9018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, T. R., R. I. Morimoto and V. Hatzimanikatis, 2005. Mathematical modeling of the eukaryotic heat-shock response: dynamics of the Hsp70 promoter. Biophys. J. 88: 1646–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarge, K. D., S. P. Murphy and R. I. Morimoto, 1993. Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 1392–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenke, T. A., and D. J. Begun, 2004. Strong selective sweep associated with a transposon insertion in Drosophila simulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 1626–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky, A., C. P. Bonin, R. S. Mann and B. Honig, 2003. Target Explorer: an automated tool for the identification of new target genes for a specified set of transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3589–3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling, A. C., D. M. Stern, I. Kiss, J. Roote, T. Laverty et al., 1995. Gene disruptions using P transposable elements: an integral component of the Drosophila Genome Project. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 10824–10830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timakov, B., X. Liu, I. Turgut and P. Zhang, 2002. Timing and targeting of P-element local transposition in the male germline cells of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 160: 1011–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower, J., G. H. Karpen, N. Craig and A. C. Spradling, 1993. Preferential transposition of Drosophila P elements to nearby chromosomal sites. Genetics 133: 347–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama, T., P. B. Becker and C. Wu, 1994. ATP-dependent nucleosome disruption at a heat-shock promoter mediated by binding of GAGA transcription factor. Nature 367: 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udvardy, A., E. Maine and P. Schedl, 1985. The 87A7 chromomere. Identification of novel chromatin structures flanking the heat shock locus that may define the boundaries of higher order domains. J. Mol. Biol. 185: 341–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez, J. M., S. Sonoda, G. Bugaisky and S. Lindquist, 1983. Is the major Drosophila heat shock protein present in cells that have not been heat shocked? J. Cell Biol. 96: 286–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker, R. A., J. Graves, W. Gibson and M. Eisenberg, 1990. Mobile element insertions causing mutations in the Drosophila suppressor of sable locus occur in DNase I hypersensitive subregions of 5′-transcribed nontranslated sequences. Genetics 126: 1071–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J. A., D. J. Taxman, Q. Lu and D. S. Gilmour, 1997. Molecular architecture of the Hsp70 promoter after deletion of the TATA box or the upstream regulation region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 3799–3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C., 1984. Two protein-binding sites in chromatin implicated in the activation of heat-shock genes. Nature 309: 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing, H. Y., D. C. Wilkerson, C. N. Mayhew, E. J. Lubert, H. S. Skaggs et al., 2005. Mechanism of Hsp70i gene bookmarking. Science 307: 421–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsepina, O. G., V. V. Velikodvorskaia, V. B. Molodtsov, D. Garbuz, D. N. Lerman et al., 2001. A Drosophila melanogaster strain from sub-equatorial Africa has exceptional thermotolerance but decreased Hsp70 expression. J. Exp. Biol. 204: 1869–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]