Abstract

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is a crucial receptor in the cell–cell interaction, a process central to the reaction to all forms of injury. Its expression is upregulated in response to a variety of inflammatory/immune mediators, including cellular stresses. The NF-κB signalling pathway is known to be important for activation of ICAM-1 transcription. Here we demonstrate that ICAM-1 induction represents a new cellular response to p53 activation and that NF-κB inhibition does not prevent the effect of p53 on ICAM-1 expression after DNA damage. Induction of ICAM-1 is abolished after treatment with the specific p53 inhibitor pifithrin-α and is abrogated in p53-deficient cell lines. Furthermore, we map two functional p53-responsive elements to the introns of the ICAM-1 gene, and show that they confer inducibility to p53 in a fashion similar to other p53 target genes. These results support an NF-κB-independent role for p53 in ICAM-1 regulation that may link p53 to ICAM-1 function in various physiological and pathological settings.

Keywords: cellular stress/ICAM-1/immune response/NF-κB/p53

Introduction

Cell–cell adhesion is vital in the generation of effective immune responses to various stimuli. Firm adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium and transmigration through the endothelium junctions represent early events in physiological (e.g. innate immune response) as well as pathological responses, such as ischaemic injury, atherosclerosis, transplant rejection and various inflammatory disorders (reviewed in Cotran and Mayadas-Norton, 1998). A key endothelial receptor in the cell–cell interaction is intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1 or CD54). ICAM-1 is a well-characterized member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) gene superfamily, which binds to the β2 leukocyte integrins, leukocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1, CD11a/CD18) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), and is used as a receptor by the major group of human rhinoviruses. Besides endothelium, it is also expressed in other cells, including antigen-presenting cells, where it functions as a co-stimulatory molecule for T-cell activation. Its significance is evident from the phenotype of ICAM-1–/– mice, which exhibit both inflammatory and immune defects (reviewed in Cotran and Mayadas-Norton, 1998).

ICAM-1 is induced by cytokines and various stress stimuli such as hypoxia, ultraviolet and ionizing radiation (Arnould et al., 1993; van de Stolpe and van der Saag, 1996; Quarmby et al., 1999; Burne et al., 2001). Although the role of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signalling cascade is pivotal in ICAM-1 activation (Roebuck and Finnegan, 1999), NF-κB-independent pathways may also participate, predominantly in stress-inducing stimuli (Hallahan et al., 1998; Takizawa et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2001). Given that similar stimuli are potent inducers of wild-type (wt) p53 (reviewed in Prives and Hall, 1999) and in view of recent reports, which demonstrate that in some situations wt p53 and NF-κB are competitor transcriptional activators hence inversely regulating each other’s activation (Wadgaonkar et al., 1999; Webster and Perkins, 1999; Shao et al., 2000), we investigated whether wt p53 could represent an alternative activator of ICAM-1.

Results

ICAM-1 mRNA and protein levels are elevated in response to artificially induced p53

Initially we examined whether activation of the p53 pathway could induce ICAM-1 expression. For this purpose, we used the tetracycline-inducible wt p53 Saos-2 cell line (Saos-2-Tet-hp53) (Ryan et al., 2000) and assayed for p53 regulation of endogenous ICAM-1 gene expression. The Saos-2 cells were chosen because they exhibit low ICAM-1 expression levels (Meneghetti et al., 1999). Upon treatment with the tetracycline analogue doxycycline (Dox), the ICAM-1 mRNA signal at 12 and 24 h was 3-fold higher than that of untreated cells, indicating that endogenous ICAM-1 is induced at the transcriptional level by p53 (Figure 1A). A comparable increase was observed in mRNA of the classical p53 target genes p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and MDM-2, which were upregulated 4- and 3-fold, respectively (Figure 1A). At the protein level, immunofluorescence of ICAM-1 in untreated Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells was weak (Figure 1B,a), but increased significantly after incubation with Dox, displaying a diffuse membrane distribution (Figure 1B,b), analogous to the mRNA analysis described in Figure 1A. Western immunoblotting of ICAM-1 neatly corroborated these results (Figure 1C). Finally, the levels of ICAM-1 induction by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were 2-fold higher than those achieved by activated p53 (Figure 1C). The latter result underlines the significance of the TNF-α pathway in triggering ICAM-1 expression (van de Stolpe and van der Saag, 1996; Cotran and Mayadas-Norton, 1998).

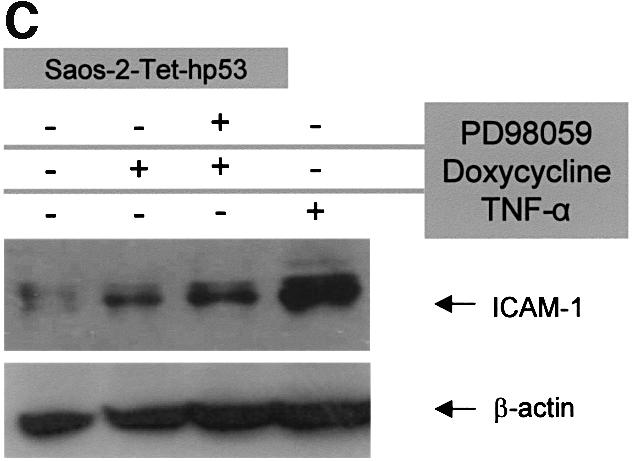

Fig. 1. Artificially expressed wt p53 induces ICAM-1 in an NF-κB-independent manner. (A) Treatment of Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells with the tetracycline analogue Dox showed a 3-fold increase in the ICAM-1 mRNA levels (assessed by comparative multiplex RT–PCR), that remained elevated after administration of the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059, which blocks the Raf/MAPK/pp90rsk/NF-κB pathway (Ryan et al., 2000). The mRNA levels of ICAM-1 in the parental Saos-2 cells were not affected by Dox (not shown). (B) Expression of ICAM-1 (green fluorescence signal) in Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells under basal conditions (a) and overexpression after Dox (b) and Dox + PD98059 treatment (c). Counterstain with DAPI (intensity normalization was based on DAPI staining). (C) Western immunoblot analysis of ICAM-1 in Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells after Dox, Dox + PD98059 and TNF-α treatment.

Artificially induced p53 upregulates ICAM-1 in an NF-κB-independent manner

Nevertheless, our finding may reflect indirect induction of ICAM-1 through NF-κB, because a recent study has demonstrated activation of NF-κB via the Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/pp90rsk cascade in response to p53 (Ryan et al., 2000). To rule out this possibility, we treated the p53-inducible Saos-2 cells with the well-characterized MEK1 inhibitor, PD98059 (Dudley et al., 1995), which has been shown to block NF-κB activation via the Raf/MAPK/pp90rsk pathway efficiently (Ghoda et al., 1997; Schouten et al., 1997; Ryan et al., 2000). The observed increase of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein levels remained unaffected in these cells after administration of PD98059, favouring an NF-κB-independent p53 effect (Figure 1A, B,c, and C).

ICAM-1 mRNA and protein levels are elevated in response to physically induced p53 due to genotoxic stress

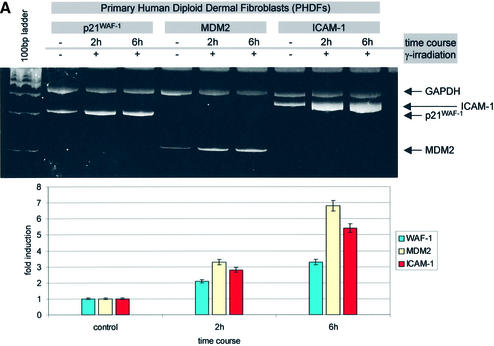

Subsequently we examined the ability of endogenous p53 to activate ICAM-1 within a physiological cellular context. To address this important issue, we developed primary human diploid dermal fibroblasts (PHDFs) and explored the status of ICAM-1 after activation of p53 in response to a potent genotoxic stress stimulus, such as γ-irradiation. Exposure of PHDFs to ionizing radiation resulted in a 2- and 3.5-fold increase of ICAM-1 mRNA at 2 and 6 h, respectively (Figure 2A), and also a 2.5-fold ICAM-1 protein level augmentation at 8 h (data not shown). The ICAM-1 mRNA levels closely resembled that of the p53 targets p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and MDM2 (Figure 2A). To exclude the possibilty that ICAM-1 was induced by other p53-independent pathways activated by radiation, we incubated the cells prior to irradiation with the specific p53 inhibitor pifithrin-α (PFT-α) (Komarov et al., 1999). Treatment with PFT-α reduced ICAM-1 and p21WAF-1/CIP-1 mRNA expression to baseline levels, clearly demonstrating that the p53 pathway is directly involved in ICAM-1 induction (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. (A) Irradiation-activated p53 in PHDFs induces a 2- and 3.5-fold increase in ICAM-1 mRNA levels, which closely resembles that of the p53 target genes p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and MDM2. (B) Pre-treatment of irradiated PHDFs with the specific p53 inhibitor PFT-α reduces p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and ICAM-1 expression to baseline levels.

Physically induced p53 upregulates ICAM-1 in an NF-κB-independent manner

Since DNA damage-induced p53 inhibits NF-κB activity (Wadgaonkar et al., 1999; Webster and Perkins, 1999; Shao et al., 2000), the above result implies that ICAM-1 induction by radiation is mediated via p53 in an NF-κB-independent manner. To strengthen this hypothesis further, we examined the effect of DNA damage (via γ-irradiation or actinomycin D treatment), first on TNF-α-induced NF-κB activity in PHDFs and, secondly, on ICAM-1 status in a p53-null and NF-κB-inactive environment, respectively.

In the first experiment, NF-κB transactivation was measured using a double ICAM-1 NF-κB-responsive element (Hou et al., 1994) attached to a secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter in a pTKSEAP transfection vector (Halazonetis, 1992). As expected, TNF-α activated the ICAM-1 NF-κB reporter construct, which was suppressed upon γ-irradiation (Figure 3A), hence confirming that p53 mediates repression of NF-κB activity following γ-irradiation (Ravi et al., 1998; Wadgaonkar et al., 1999; Webster and Perkins, 1999; Shao et al., 2000).

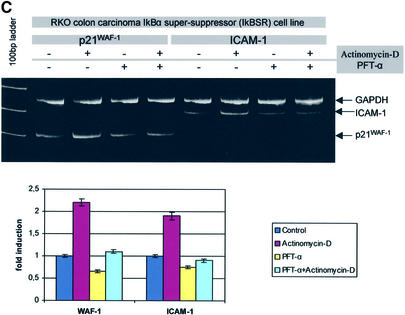

Fig. 3. Wt p53 and not NF-κB activity is necessary for DNA damage-induced ICAM-1 expression (irradiation or actinomycin D treatment). (A) Irradiation-induced p53 (upper right inset blot) suppresses TNF-α-triggered NF-κB activity. (B) ICAM-1, p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and MDM2 are not induced in a p53-null environment (Saos-2) following γ-irradiation, as determined by the target/GAPDH ratio which was equal in pre- and post-irradiation measurements. (C) Low dose of the DNA-damaging agent actinomycin D-induced p53 activates p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and ICAM-1 mRNA expression in the NF-κB-inactive environment of the RKO-IκBαSR cells, which falls to baseline levels after treatment with PFT-α.

In the second set of experiments, the pre- and post-irradiation ICAM-1 levels of the p53-null cell lines, Saos-2 (Figure 3B) and the human erythroleukaemic cells K562 (data not shown), were constant at 2 and 6 h. These time points were selected because ICAM-1 induction represents an early immune reaction (van de Stolpe and van der Saag, 1996). On the other hand, the RKO colon carcinoma cell line stably expressing the mutant form of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα super-repressor (IκBαSR) (RKO-IκBαSR), which cannot be phosphorylated and thus ubiquitylated, was used to assess the activity of p53 in an NF-κB-inactive environment (Ryan et al., 2000). Exposure of RKO-IκBαSR cells to a low dose of the DNA-damaging agent actinomycin D (10 nM) resulted in a 2.3- and 2-fold increase of p21WAF-1/CIP-1 and ICAM-1 mRNA at 6 h, respectively, which dropped to baseline levels after PFT-α treatment (Figure 3C). Given that NF-κB is intact in the Saos-2 and K562 cell lines (Meichle et al., 1990; Ryan et al., 2000) and that NF-κB is constantly inactivated in RKO-IκBαSR cells (Ryan et al., 2000), our results underline the significance of wt p53 in ICAM-1 induction by certain stress stimuli.

Human ICAM-1 intronic sequences contain multiple p53-binding sites as predicted by in silico analysis

The wt p53 protein is a critical transcription factor that responds to signals from a wide range of cellular stresses and allows the cell to cope with these stimuli by activating a set of target genes, facilitating adaptive and protective responses (reviewed in Prives and Hall, 1999). It is well established that the p53 protein activates its targets by binding to specific DNA regulatory elements located in the 5′-flanking region and/or within the intronic sequences of the target gene. Each p53-responsive element (p53RE) contains two copies (half-binding sites) of the motif (Pu)3-C-(A/T)-(T/A)-G-(Py)3, separated by 0–13 nucleotides (el-Deiry consensus sequence; el-Deiry et al., 1992). In addition to the above mechanism, a recent study presented for the first time evidence that p53 may be implicated in mRNA stabilization of the p21WAF-1/CIP-1 gene; however, this phenomenon is mediated via a tyrosine kinase/phosphatase regulatory system (Gorospe et al., 1998), whereas ICAM-1 mRNA stabilization, which has been reported to occur, was shown to involve a serine/threonine phosphorylation pathway, and inhibition of tyrosine kinases and phosphatases had no effect on it (Ohh and Takei, 1996). Furthermore, according to a recent study by Tanabe et al. (1997), ICAM-1 is initially transcriptionally upregulated by cytokines or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) within a time course of 4 h. The following increase in ICAM-1 mRNA levels (up to 24 h) is due to post-transcriptional stabilization. In our analysis, the time course for studying ICAM-1 mRNA induction involved an initial time period of 2 and 6 h (Figure 2), suggesting that the observed upregulation of ICAM-1 was due, at least in part, to transcriptional activation. Taken together, these latter reports, the data from the cellular systems we employed as well as the biochemical nature of p53 as a transcription factor prompted us to search for the existence of putative p53REs in the ICAM-1 gene.

In silico examination of the ICAM-1 genomic sequence revealed three potential p53REs in the first and second introns (Figure 4). Although each of these putative elements diverged from the consensus p53-binding site by three nucleotides, the central C(A/T)(T/A)G motif, which is crucial for DNA binding (Cho et al., 1994), was intact in all of them. In addition, using the extended set of criteria proposed by Bourdon et al. (1997), we found additional p53 putative binding sites flanking the 5′ end of the sequences resembling the el-Deiry element (Figure 4). Notably, the topological organization of the ICAM-1 putative p53REs resembled that of the p53 target gene insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGF-BP3) (Buckbinder et al., 1995).

Fig. 4. Genomic structure of the ICAM-1 gene region containing the putative p53REs (contig accession No. AC011511). The ICAM-1 genomic region was found after pairwise homology search (pairwise nucleotide BLAST) of genomic database deposits with the ICAM-1 mRNA sequence (accession No. J03132). The p53REs resembling to a greater extent the classical p53 consensus RRRCWWGYYY (p53CON) (el-Deiry et al., 1992) are marked in red. Additional p53 half-binding sites that match the criteria set by Bourdon et al. (1997) are marked in blue. The mismatches from p53CON are marked in yellow.

Functional analysis of the predicted p53REs of human ICAM-1

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis employing in vitro translated human p53 protein, anti-p53 monoclonal antibody DO-1 and competition with mutant (mt) consensus oligonucleotides revealed that the predicted DNA elements are indeed specific p53-binding sites (Figure 5A). In addition, all the elements conferred inducibility specifically by wt p53 in cis to a heterologous promoter when introduced into the human p53-null osteosarcoma cell line Saos-2 (Figure 5B), confirming that these REs may function as active p53-binding sites. Although ICAM-1 p53RE-A1, -B1 and -C conferred weaker inducibility than the element of the p53 target gene p21WAF-1/CIP-1, the extended p53-responsive regions (p53RE-A2 and -B2; Figure 4) displayed an increased response, raising the possibility that these binding sites may cooperate (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. In vitro characterization of the p53-binding sites within the intronic sequences of the ICAM-1 gene. (A) EMSA showing specific binding of in vitro produced wt p53 to the identified ICAM-1p53REs (A1, B1, C; el-Deiry consensus). Left panel (A1 probe): lane 1, no retarded ICAM-1p53RE-A1 band in the presence of plain rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RR Lysate); lane 2, in vitro-translated wt p53 protein binds to the labelled specific element in the presence of monoclonal antibody (Ab) PAb421, generating a retarded species; lanes 3 and 4, 50-fold molar excess of unlabelled ICAM-1p53RE-A1 completely abolishes the retarded species, whereas the same amount of mtICAM-1p53RE-A1 [harbouring a mutation at position 4(C) and 7(G) of the consensus] does not affect its formation, demonstrating the specificity of binding; lane 5, in vitro-translated mt p53 protein (V173E) fails to bind the ICAM-1p53RE-A1 element; lane 6, addition of the anti-p53 Ab DO-1, in the presence of PAb421, ‘super-shifted’ the retarded species, verifying the presence of p53 in the DNA–protein complex. Middle panel (B1 probe): lane 1, no retarded ICAM-1p53RE-B1 band in the presence of RR lysate; lane 2, in vitro-translated wt p53 protein binds to the labelled specific element in the presence of monoclonal Ab PAb421, generating a retarded species; lanes 3 and 4, 50-fold molar excess of unlabelled ICAM-1p53RE-B1 completely abolishes the retarded species, whereas the same amount of mtICAM-1p53RE-B1 [harbouring a mutation at position 4(C) and 7(G) of the consensus] does not affect its formation; lane 5, in vitro-translated mt p53 protein (V173E) fails to bind the ICAM-1p53RE-B1 element; lane 6, addition of the anti-p53 Ab DO-1, in the presence of PAb421, ‘super-shifted’ the retarded species. Right panel (C probe): lane 1, in vitro-translated wt p53 protein binds to the labelled ICAM-1p53RE-C element in the presence of monoclonal Ab PAb421, generating a retarded species; lanes 2 and 3, 50-fold molar excess of unlabelled ICAM-1p53RE-C completely abolishes the retarded species, whereas the same amount of mtICAM-1p53RE-C [harbouring a mutation at position 4(C) and 7(G) of the consensus] does not affect its formation; lane 4, in vitro-translated mt p53 protein (V173E) fails to bind the ICAM-1p53RE-C element; lane 5, addition of the anti-p53 Ab DO-1, in the presence of PAb421, ‘super-shifted’ the retarded species. (B) Transient transfection assays demonstrating that the ICAM-1p53REs confer wt p53 inducibility in cis to a heterologous promoter. Notably, the ICAM-1p53REs which bear the sequences fulfilling the criteria of Bourdon et al. (1997), i.e. A2 and B2, confer stronger inducibility than the ICAM-1p53REs comprising only the el-Deiry consensus (i.e. A1 and B1), whereas mt p53V173E has no effect. Results shown are an average of three independent experiments.

Nevertheless, the mere presence of a p53RE, which demonstrates transcriptional activity in transient assays, does not necessarily imply that it will function efficiently within the context of organized chromatin (Cook et al., 1999). To clarify the latter issue, we analysed the interaction of p53 with the putative p53REs by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments. Under the stringent conditions employed, p53 interacted specifically with p53RE-A and p53RE-B (Figure 6). Interestingly, the PCR signal from RE-A was equivalent to the recently identified pentanucleotide repeat p53RE (penta-p53RE) of PIG3 (p53-induced gene 3) which, despite its moderate resemblance to the classical p53 el-Deiry consensus, was necessary and sufficient for transcriptional activation of PIG3 (Contente et al., 2002) (Figure 6). The signal from p53RE-B was slightly weaker than that of p53RE-A and PIG3 penta-p53RE (Figure 6). On the other hand, the putative p53RE-C did not co-precipitate with p53, suggesting that it is not functional within the context of organized chromatin. Thus, our in vivo findings (Figures 1–3) combined with the data from the above experiments (Figures 5 and 6) indicate that p53 most probably mediates its effects on ICAM-1 directly via the p53REs A and B.

Fig. 6. In vivo characterization of the p53-binding sites within the intronic sequences of the ICAM-1 gene by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Lanes 1–10: ChIP assay in Saos-2 Tet hp53; lane 1, marker; lane 2, p21WAF-1/CIP-1 p53RE (positive control); lane 3, PIG3 penta-p53RE (positive control; Contente et al., 2002); lane 4, positive PCR signal from p53 co-precipitated ICAM-1 p53RE-A with p53 Ab PAb421; lanes 5 and 6, absence of an ICAM-1 p53RE-A PCR signal from precipitated DNA with no p53 Ab and with non-specific Ab Pab491, respectively (negative controls); lane 7, positive PCR signal from p53 co-precipitated ICAM-1 p53RE-B with p53 Ab PAb421; lanes 8 and 9, absence of an ICAM-1 p53RE-B PCR signal from precipitated DNA with no p53 Ab and with non-specific Ab Pab491, respectively; lane 10, no PCR signal from a non-specific gene region (NSGR) of p21WAF-1/CIP-1 (negative control). Lanes 11–15: ChIP assay in parental Saos-2 (p53 null) (negative control); lanes 11 and 12, PCR signals of ICAM-1 p53RE-A and -B from genomic DNA derived from Saos-2 (control PCRs); lanes 13–15, absence of a p21WAF-1/CIP-1 p53RE, ICAM-1 p53RE-A and ICAM-1 p53RE-B PCR signal from precipitated DNA with p53 Ab PAb421, respectively. Note: in lane 3, the PIG3 element exhibits a heterozygous pattern due to the polymorphic genetic constitution of this locus in the Saos-2 cell line. The faster migrating allele (118 bp) corresponds to 10 pentanucleotide repeats, while the lower mobility one (143 bp) represents 15 pentanucleotide repeats (Contente et al., 2002). The higher intensity of the 143 bp allele reflects a direct correlation between increase in pentanucleotide repetitions and enhanced p53 binding, hence transcriptional activation of PIG3 (Contente et al., 2002).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that induction of ICAM-1, a well-established NF-κB target (Roebuck and Finnegan, 1999) and an adhesion molecule implicated in vital aspects of the immune response (Cotran and Mayadas-Norton, 1998), represents a novel cellular response to p53 activation. Based on our recent data, which show that NF-κB acts as a downstream effector of p53 (Ryan et al., 2000), we established that this p53 effect is independent of NF-κB activity. Furthermore, we identified two p53 functional REs within the intronic sequences of ICAM-1, implying that the effect of p53 is direct and mediated by these binding sites.

In view of the competitive relationship between p53 and NF-κB in certain circumstances (Wadgaonkar et al., 1999; Webster and Perkins, 1999; Shao et al., 2000), induction of ICAM-1 by radiation in cells with wt p53 but not in the p53-null cellular environment puzzled us, because two recent reports suggest that induction by radiation is mediated through NF-κB (Baeuml et al., 1997; Hallahan et al., 1998). A possible explanation might be that in these latter studies, only the promoter region was examined, excluding regulatory elements outside of it. Alternatively, NF-κB may act as an additional downstream p53 mediator, which is not activated by specific stress stimuli (e.g. X-rays) in the absence of p53. Moreover, it should be noted that in one of the aforementioned studies, treatment with the NF-κB inhibitors pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) and N-acetylo-cysteine (NAC) resulted in increased ICAM-1 expression in irradiated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), supporting an NF-κB-independent mechanism (Hallahan et al., 1998). Although this phenomenon was attributed partially to activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) by PDTC (Munoz et al., 1996), our data support a model where ICAM-1 upregulation can be achieved via DNA damage-induced p53. In favour of this model, a recent report demonstrated that p53 activation was accompanied by inhibition of AP-1-binding activity, due to competition for the co-activator p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) (Avantaggiati et al., 1997). Finally, the study of Epperly et al. (1999), who demonstrated that ICAM-1 was constitutively expressed in p53+/+ bone marrow stromal cell lines but not in p53–/– cells, further supports our model.

Our finding raises two questions. First, which conditions will influence the regulatory effect of p53 and which that of NF-κB and AP-1 on ICAM-1 expression, and, secondly, how does ICAM-1 induction relate to p53 biology?

The answer to the first question possibly lies in the appropriate stimuli and the cellular context. The former will determine the relative levels of the stress-regulated transcription factors, thus dictating the outcome of their competition for the limiting cellular pool of the co-activator p300/CBP (Avantaggiati et al., 1997; Ravi et al., 1998; Wadgaonkar et al., 1999; Webster and Perkins, 1999; Shao et al., 2000). For example, cytokines will activate predominantly NF-κB, whereas DNA damage will induce mainly p53. The cell type may also affect oxidant stress regulation of ICAM-1 by differentially activating NF-κB and AP-1 (Roebuck, 1999). A similar effect may also apply for p53.

Regarding the second point, the apparent p53–ICAM-1 link suggests either that ICAM-1 may participate in p53-dependent cellular processes such as growth arrest and apoptosis, and/or that p53 may have a role in certain inflammatory conditions. It is well documented that cellular interactions influence a variety of signalling events including those engaged in survival (Juliano, 2002). Several groups have shown that an interplay between cell adhesion pathways and p53 activity exists (Giaccia and Kastan, 1998). Although the signal transduction cascades involved remain elusive, there are indications that ICAM-1 also participates in such a process. Specifically, ICAM-1 expression in cells of mesenchymal origin (osteoblasts and synovial cells) is accompanied by p53 and p21WAF-1/CIP-1 upregulation and cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase (Tanaka et al., 2000a,b). All these results imply that a p53–ICAM-1 regulatory circuitry may operate in certain cellular systems. Whether this ‘functional cross-talk’ occurs through a positive feedback loop awaits determination. In certain cell types, mainly of mesenchymal origin, integrin-mediated adhesion is a prerequisite for p53-mediated apoptosis in response to lethal DNA damage (Lewis et al., 2002). It has been postulated that in these cases, poorly adherent cells may escape killing induced by DNA damage therapy and that such cells may represent an ideal target for accumulation of mutations which would thereby accelerate cancer progression (Lewis et al., 2002). Induction of ICAM-1 by p53 may possibly act as an additional link with the cellular microenvironment participating in the aforementioned cell adhesion-dependent apoptotic mechanism, probably by enhancing adhesiveness for leukocytes and monocytes. Although for a long time apoptosis was considered as ‘clean’ and non-inflammatory cell death, recent reports support the coupling between programmed cell death and an inflammatory reaction (Loffing et al., 1996). In accordance with that, the DNA damage- mediated apoptosis of endothelial cells is associated with upregulation of ICAM-1 and hyperadhesiveness for monocytic cells (Hebert et al., 1998). Interestingly, endothelial apoptosis is also accompanied by augmented levels of interleukin (IL)-1β-converting enzyme (ICE/caspase-1), a member of the caspase family with a central role in apoptosis, and a recently identified p53 target (Hebert et al., 1998; Gupta et al., 2001). Furthermore, in light of the notion that apoptotic bodies may represent vehicles of genomic instability, by incorporating their DNA load into neighbouring cells (Holmgren et al., 1999; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000), upregulation of ICAM-1 by p53 may participate in the ‘scavenging’ of this potentially carcinogenetic material. Thus, given the fundamental role of ICAM-1 in the immune response (Cotran and Mayadas-Norton, 1998) and the significance of mutant p53 in tumour development (Prives and Hall, 1999), it becomes clear that the p53–ICAM-1 functional relationship may be important for immune surveillance. In this vein, it has been shown that all childhood Burkitt’s lymphomas with p53 mutations were also ICAM-1 negative and were associated with a more aggressive phenotype (Kaneko et al., 1996). Moreover, activation of ICAM-1 by p53 may be implicated in tumour-targeted inflammation during phase I clinical trials with CM101, a bacterial polysaccharide exotoxin, shown to induce increased p53-binding activity within the tumour coupled with leukocyte infiltration (Yakes et al., 2000). In this way, p53 may act not only as an intracellular ‘guardian’, but also as an intercellular one. p53 activation of ICAM-1 may also play a role in certain inflammatory conditions. Atherosclerosis, a well-established chronic inflammatory disease, possibly represents such a case (Hansson, 2001). Several works during the last decade suggested that ICAM-1 is critical for atherogenesis (Bourdillon et al., 2000; Collins et al., 2000; Kitagawa et al., 2002). In situ studies have demonstrated increased expression of ICAM-1 on the cells comprising the atherosclerotic lesions, whereas normal arterial endothelial cells and intimal smooth muscle outside the plaques exhibited weak or negative staining reactions (Poston et al., 1992; Watanade and Fan, 1998). Several lines of evidence indicate, in certain cells of the lesions, the existence of NF-κB-independent ICAM-1 stimulatory pathways (Rolfe et al., 2000; Voisard et al., 2001). In this regard, various studies have revealed accumulation of active wt p53 in all cellular populations of the atheromatous plaques (Speir et al., 1994; Ihling et al., 1997, 1998; Tabas, 2001). In some of these cases, activation of wt p53 possibly represents a ‘protective’ response to DNA breakage due to oxidative stress (Ihling et al., 1997, 1998). However, this ‘protective’ response may have certain side effects in an inappropriate cellular environment (e.g. hypercholesterolaemia), one of which, according to our model, could be upregulation of ICAM-1 (Yuan et al., 2001).

Another phenomenon wherein p53 could be linked with ICAM-1 expression is collateral artery growth (also known as arteriogenesis), which represents a compensatory response to arterial stenosis or occlusion (Schaper and Scholz, 1997). According to the current model of arteriogenesis, artery occlusion is followed by an abrupt increase of fluid shear stress along the arteriolar network, which stimulates upregulation of adhesion molecules, including ICAM-1, on the endothelial cells of the collateral vessels. Subsequently, monocytes accumulate and secrete growth factors which trigger a chain of remodelling events leading to artery growth from pre-existing arterioles (Arras et al., 1998; Scholz et al., 2000). The molecular connection between mechanical stimulation of endothelial cells and ICAM-1 expression may be activation of p53 protein because laminar shear stress has been shown to induce p53 in a magnitude- and time-dependent manner in endothelial cells (Lin et al., 2000).

Finally, cellular senescence and ageing may represent additional biological routes where the p53–ICAM-1 link may operate. Indeed, ICAM-1 is overexpressed in senescent cells and aged tissues (Saito and Papaconstantinou, 2001; Minamino et al., 2002), and recent reports strongly implicate p53 in the ageing process (Sharpless and DePinho, 2002; Tyner et al., 2002).

It remains to be seen whether this new proposed role for p53 could be translated into therapeutic advances. To this end, by interfering with the activity of NF-κB, which is increased in many tumour types (Yamamoto and Gaynor, 2001), and restoring the function of p53 that is mutated in >50% of human malignant neoplasias (Prives and Hall, 1999; Shao et al., 2000; Papavassiliou, 2000; Karamouzis et al., 2002), for instance by locally injecting adenovirus vectors carrying wt p53, one may achieve massive apoptosis within the tumour followed by targeted recruitment of leukocytes, which would remove the potentially harmful apoptotic debris.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and specific treatment

The Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells were used to activate p53 artificially (Ryan et al., 2000). Cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies). In one set of experiments, induction of p53 was obtained by using 800 ng/ml Dox. Blocking of NF-κB activity was achieved by adding 100 µM PD98059 (Ryan et al., 2000). In another set of experiments, the cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 16 h before harvesting.

PHDFs were developed from explants derived from the inner left arm of consenting healthy adult volunteers and routinely cultured in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), as described previously (Kletsas et al., 1998). The p53-null cell lines, Saos-2 and K562 (American Type Culture Collection), and the RKO-IκBαSR cells (see text) were cultivated in DMEM.

Confluent PHDF, Saos-2 and K562 cultures were irradiated at a dose of 10 Gy (19.7 Gy/min) in a Gamma Chamber 4000A (Isotope Group, Bhabha Atomic Research Company, Trombay, Bombay, India). Additionally, confluent RKO-IκBαSR cultures were treated with a low dose of the DNA-damaging agent actinomycin D (10 nM), as described previously (Ryan et al., 2000). Blocking of p53-dependent transcriptional activity was achieved by adding 20 µM of the specific p53 inhibitor PFT-α (Tocris, AlterChem, Greece) 30 min before irradiation (Komarov et al., 1999).

mRNA analysis

The mRNA levels of the examined genes were assessed using a comparative multiplex RT–PCR method, as described previously (Gorgoulis et al., 2001). Briefly, RNA was extracted using an easyRNA extraction kit (Qiagen) and subsequently cDNA was generated using the M-MLV Superscript II RT according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). The GAPDH gene was used as reference gene for all PCRs. The following amplimers were designed using the Oligo 4.01 software (National Biosciences Inc., Plymouth, MN): GAPDH (accession No. XM_033263) forward (F), CAT CTC TGC CCC CTC TGC TG (position 830), reverse (R), CGA CGC CTG CTT CAC CAC CT (position 411), product length 438 bp; p53 (accession No. XM_058834) F, TGG GGG CAG CTC GTG GTG A (position 913), R, TCT GGC CCC TCC TCA GCA TC (position 589), product length 342 bp, annealing temperature 60°C; p21WAF-1/CIP-1 (accession No. U03106) F, CTG CCG CCG CCT CTT C (position 126), R, CTG AGC GAG GCA CAA GGG TA (position 426), product length 319 bp, annealing temperature 61°C, plus 5% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO); MDM2 (accession No. XM_083867) F, GCA GGG GAG AGT GAT ACA GA (position 1152), R, GCT TGT GTT GAG TTT TCC AGT (position 1343), product length 211 bp, annealing temperature 58°C; ICAM-1 (accession No. X06990) F, TGG TAG CAG CCG CAG TCA TA (position 1469), R, CTC CTT CCT CTT GGC TTA GT (position 1829), product length 377 bp, annealing temperature 57°C.

PCR products were electrophoresed in a non-denaturing 8% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (19:1) gel. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and images were captured with a digital camera (Kodak) and processed with a gel documentation software (Kodak).

Indirect immunofluorescence

Saos-2-Tet-hp53 cells were cultured on 15 mm glass coverslips in 6-well culture plates. Following incubation with Dox and Dox + PD98059, cells were fixed with 100% methanol. The primary antibody used for targeting ICAM-1 was the mouse monoclonal anti-ICAM-1 (G-5) (class IgG2a; epitope, amino acids 258–365, human origin, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:100 dilution. The antigen–primary antibody complex was detected with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody at a 1:250 dilution. Counterstain was obtained with 100 ng/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma). Microscopic observation was performed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope.

Western immunoblot analysis

Western immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (Gorgoulis et al., 1998). Briefly, cell homogenates were resolved on 4–20% gradient PAGER™ Gold pre-cast gels (BioWhittaker) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Protran BA85, Schleicher & Schuell). The antibodies used comprised the anti-p53 (DO-7) (class IgG2b; epitope, amino acids 1–45, human origin, Dako, Denmark) and anti-ICAM-1 (G-5) (class IgG2a; epitope, amino acids 258–365, human origin, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) mouse monoclonal antibodies at a 1:100 dilution. Equal loading of total protein per sample was monitored with the anti-actin C-2 mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the human tumour cell line Jurkat was used as a positive control. Signal development was performed with the enhanced SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

In silico homology search

Identification of the ICAM-1 genomic locus (contig accession No. AC011511, 12/14 July 2002), bearing the putative p53REs, was found after homology search (BLASTN, version 2.2.1) of DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank genomic nucleotide deposits with the ICAM-1 mRNA sequence (accession No. J03132). The three putative p53REs were recognised with a nucleotide motif homology search tool (OMIGA, version 2; Genetics Computer Group Inc., Madison, WI).

EMSAs

EMSAs were performed as previously described (Gorgoulis et al., 1998). Briefly, 1 ng of [α-32P]ATP end-labelled ICAM-1p53RE (A1, B1, C; Figures 4 and 5A) and 4 µl of in vitro-translated wt p53 with 100 ng of purified monoclonal antibody Pab421 were incubated for 10 min in order to activate specific DNA binding of p53 protein. Competition experiments were performed by pre-incubating PAb421-activated extracts with a 50-fold molar excess of unlabelled oligonucleotides (wtICAM-1p53REs or mtICAM-1p53REs). For ‘supershift’ experiments, pre-incubations were performed with 100 ng of anti-p53 antibody DO1. Protein–DNA binding reactions were resolved on a 4% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel followed by exposure of the dried gel to X-ray film.

Transient transfection assays

The putative ICAM-1p53REs (Figures 4 and 5B) were inserted into the EcoRV site of the polylinker of the SEAP reporter gene (pTKSEAP, kindly provided by T.D.Halazonetis; Halazonetis, 1992). The expression constructs were co-transfected with 1 µg of each SEAP reporter plasmid into the p53-null cell line Saos-2 using the lipofectin reagent (Life Technologies). Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined 48 h later, as described previously (Zacharatos et al., 1999).

PHDFs were transfected with 2 µg of ICAM-1NF-κB/pTKSEAP reporter construct using the lipofectin reagent. The reporter plasmid was constructed by cloning a double NF-κB site into the EcoRV site of pTKSEAP. After 24 h, the cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for an additional 16 h and then irradiated. Cells were harvested 8 h later.

The pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (Promega) was used to monitor the transfection efficiencies. The pCB6hp53mtV173E expression vector (derived from pCB6 and pCB6hp53wt; a generous gift from M.Oren) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis, as described previously (Gorgoulis et al., 1998).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

See Supplementary data, available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank L.Philipson for helpful comments on the manuscript, and K.Evangelou, M.Gazouli and S.Kokotas for excellent technical assistance. This work was funded in part by a research grant from the ‘Alexander S.Onassis Public Benefit Foundation’ (Liechtenstein/Greece) to A.G.P. P.Z. and A.K. are recipients of a postdoctoral scholarship from the SSF, Greece.

References

- Arnould T., Michiels,C. and Remacle,J. (1993) Increased PMN adherence on endothelial cells after hypoxia: involvement of PAF, CD18/CD11b and ICAM-1. Am. J. Physiol., 264, C1102–C1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arras M., Ito,W.D., Scholz,D., Winkler,B., Schaper,J. and Schaper,W. (1998) Monocyte activation in angiogenesis and collateral growth in the rabbit hindlimb. J. Clin. Invest., 101, 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avantaggiati M.L., Ogryzko,V., Gardner,K., Giordano,A., Levine,A.S. and Kelly,K. (1997) Recruitment of p300/CBP in p53-dependent signal pathways. Cell, 89, 1175–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuml H., Behrends,U., Peter,R.U., Mueller,S., Kammerbauer,C., Caughman,S.W. and Degitz,K. (1997) Ionizing radiation induces, via generation of reactive oxygen intermediates, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) gene transcription and NF κB-like binding activity in the ICAM-1 transcriptional regulatory region. Free Radical Res., 27, 127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdillon M.C., Poston,R.N., Covacho,C., Chignier,E., Bricca,G. and McGregor,J.L. (2000) ICAM-1 deficiency reduces atherosclerotic lesions in double-knockout mice (ApoE(–/–)/ICAM-1(–/–)) fed a fat or a chow diet. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 20, 2630–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon J.C., Deguin-Chambon,V., Lelong,J.C., Dessen,P., May,P., Debuire,B. and May,E. (1997) Further characterisation of the p53 responsive element—identification of new candidate genes for trans-activation by p53. Oncogene, 14, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckbinder L., Talbott,R., Velasco-Miguel,S., Takenaka,I., Faha,B., Seizinger,B.R. and Kley,N. (1995) Induction of the growth inhibitor IGF-binding protein 3 by p53. Nature, 377, 646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne M.J., Elghandour,A., Haq,M., Saba,S.R., Norman,J., Condon,T., Bennett,F. and Rabb,H. (2001) IL-1 and TNF independent pathways mediate ICAM-1/VCAM-1 up-regulation in ischemia reperfusion injury. J. Leukoc. Biol., 70, 192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y., Gorina,S., Jeffrey,P.D. and Pavletich,N.P. (1994) Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor–DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science, 265, 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R.G., Velji,R., Guevara,N.V., Hicks,M.J., Chan,L. and Beaudet,A.L. (2000) P-selectin or intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 deficiency substantially protects against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med., 191, 189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contente A., Dittmer,A., Koch,M.C., Roth,J. and Dobbelstein,M. (2002) A polymorphic microsatellite that mediates induction of PIG3 by p53. Nat. Genet., 30, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.L., Zhang,Z., Alam,J. and Re,R.N. (1999) Effects of chromosomal integration site upon p53 interactions with DNA consensus sequence homologies. Oncogene, 18, 2373–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotran R.S. and Mayadas-Norton,T. (1998) Endothelial adhesion molecules in health and disease. Pathol. Biol. (Paris), 46, 164–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley D.T., Pang,L., Decker,S.J., Bridges,A.J. and Saltiel,A.R. (1995) A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 7686–7689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Deiry W.S., Kern,S.E., Pietenpol,J.A., Kinzler,K.W. and Vogelstein,B. (1992) Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat. Genet., 1, 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperly M.W., Bray,J.A., Carlos,T.M., Prochownik,E. and Greenberger,J.S. (1999) Biology of marrow stromal cell lines derived from long-term bone marrow cultures of Trp53-deficient mice. Radiat. Res., 152, 29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoda L., Lin,X. and Greene,W.C. (1997) The 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (pp90rsk) phosphorylates the N-terminal regulatory domain of IκBα and stimulates its degradation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 21281–21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccia A.J. and Kastan,M.B. (1998) The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev., 12, 2973–2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgoulis V.G. et al. (1998) Effects of p53 mutants derived from lung carcinomas on the p53-responsive element (p53RE) of the MDM2 gene. Br. J. Cancer, 77, 374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgoulis V.G. et al. (2001) Deregulated expression of c-mos in non-small cell lung carcinomas: relationship with p53 status, genomic instability and tumor kinetics. Cancer Res., 61, 538–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorospe M., Wang,X. and Holbrook,N.J. (1998) p53-dependent elevation of p21Waf1 expression by UV light is mediated through mRNA stabilization and involves a vanadate-sensitive regulatory system. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 1400–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Radha,V., Furukawa,Y. and Swarup,G. (2001) Direct transcriptional activation of human caspase-1 by tumor suppressor p53. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10585–10588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halazonetis T.D. (1992) An enhancer ‘core’ DNA-binding and transcriptional activity is induced upon transformation of rat embryo fibroblasts. Anticancer Res., 12, 285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan D.E., Virudachalam,S. and Kuchibhotla,J. (1998) Nuclear factor κB dominant negative genetic constructs inhibit X-ray induction of cell adhesion molecules in the vascular endothelium. Cancer Res., 58, 5484–5488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. and Weinberg,R.A. (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell, 100, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G.K. (2001) Immune mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 21, 1876–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert M.-J., Gullans,S.R., Mackenzie,H.S. and Brady,H.R. (1998) Apoptosis of endothelial cells is associated with paracrine induction of adhesion molecules. Am. J. Pathol., 152, 523–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren L., Szeles,A., Rajnavolgyi,E., Folkman,J., Klein,G., Ernberg,I. and Falk,K.I. (1999) Horizontal transfer of DNA by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. Blood, 93, 3956–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Baichwal,V. and Cao,Z. (1994) Regulatory elements and transcription factors controlling basal and cytokine-induced expression of the gene encoding intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11641–11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihling C., Menzel,G., Wellens,E., Monting,J.-S., Schaefer,H.E. and Zeiher,A.M. (1997) Topographical association between the cyclin-dependent kinases inhibitor p21, p53 accumulation and the cellular proliferation in human atherosclerotic tissue. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 17, 2218–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihling C., Handeler,J., Menzel,G., Hess,R.D., Fraedrich,G., Schaefer,H.E. and Zeiher,A.M. (1998) Co-expression of p53 and MDM2 in human atherosclerosis: implications for the regulation of cellularity of atherosclerotic lesions. J. Pathol., 185, 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano R.L. (2002) Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 42, 283–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko H. et al. (1996) Lack of CD54 expression and mutation of p53 gene relate to the prognosis of childhood Burkitt’s lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma, 21, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamouzis M.V., Gorgoulis,V.G. and Papavassiliou,A.G. (2002) Transcription factors and neoplasia: vistas in novel drug design. Clin. Cancer Res., 8, 949–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K., Matsumoto,M., Sasaki,T., Hashimoto,H., Kuwabara,K., Ohtsuki,T. and Hori,M. (2002) Involvement of ICAM-1 in the progression of atherosclerosis in APOE-knockout mice. Atherosclerosis, 160, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kletsas D., Caselgrandi,E., Barbieri,D., Stathakos,D., Franceschi,C. and Ottaviani,E. (1998) Neutral endopeptidase-24.11 (NEP) activity in human fibroblasts during development and ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev., 102, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarov P.G., Komarova,E.A., Kondratov,R.V., Christov-Tselkov,K., Coon,J.S., Chernov,M.V. and Gudkov,A.V. (1999) A chemical inhibitor of p53 that protects mice from the side effect of cancer therapy. Science, 285, 1733–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.M., Truong,T.N. and Schwartz,M.A. (2002) Integrins regulate the apoptotic response to DNA damage through modulation of p53. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 3627–3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K., Hsu,P.-P., Chen,B.P., Yuan,S., Usami,S., Shyy,J.Y.-J., Li,Y.-S. and Chien,S. (2000) Molecular mechanism of endothelial growth arrest by laminar shear stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 9385–9389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffing J., Loffing-Cueni,D., Hegyi,I., Kaplan,M.R., Hebert,S.C., Le Hir,M. and Kaissling,B. (1996) Thiazide treatment of rats provokes apoptosis in distal tubule cells. Kidney Int., 50, 1180–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichle A., Schutze,S., Hensel,G., Brunsing,D. and Kronke,M. (1990) Protein kinase C-independent activation of nuclear factor κB by tumor necrosis factor. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 8339–8343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghetti A., Mariani,E., Santi,S., Riccio,M., Cattini,L., Paoletti,S. and Facchini,A. (1999) NK binding capacity and lytic activity depend on the expression of ICAM-1 on target bone tumours. Int. J. Oncol., 15, 909–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamino T., Miyauchi,H., Yoshida,T., Ishida,Y., Yoshida,H. and Komuro,I. (2002) Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation, 105, 1541–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz C., Castellanos,M.C., Alfranca,A., Vara,A., Esteban,M.A., Redondo,J.M. and de Landazuri,M.O. (1996) Transcriptional up-regulation of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 in human endothelial cells by the antioxidant pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate involves the activation of activating protein-1. J. Immunol., 157, 3587–3597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohh M. and Takei,F. (1996) New insights into the regulation of ICAM-1 gene expression. Leuk. Lymphoma, 20, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papavassiliou A.G. (2000) p53-targeted drugs: intelligent weapons in the tumor-suppressing arsenal. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol., 126, 117–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston R.N., Haskard,D.O., Coucher,J.R., Gall,N.P. and Johnson-Tidey,R.R. (1992) Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in atherosclerotic plaques. Am. J. Pathol., 140, 665–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives C. and Hall,P.A. (1999) The p53 pathway. J. Pathol., 187, 112–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarmby S., Kumar,P. and Kumar,S. (1999) Radiation-induced normal tissue injury: role of adhesion molecules in leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions. Int. J. Cancer, 82, 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi R., Mookerjee,B., van Hensbergen,Y., Bedi,G.C., Giordano,A., el-Deiry,W.S., Fuchs,E.J. and Bedi,A. (1998) p53-mediated repression of nuclear factor-κB RelA via the transcriptional integrator p300. Cancer Res., 58, 4531–4536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck K.A. (1999) Oxidant stress regulation of IL-8 and ICAM-1 gene expression: differential activation and binding of the transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB. Int. J. Mol. Med., 4, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck K.A. and Finnegan,A. (1999) Regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) gene expression. J. Leukoc. Biol., 66, 876–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe B.E., Muddiman,J.D., Smith,N.J., Campbell,G.R. and Campbell,J.H. (2000) ICAM-1 expression by vascular smooth muscle cells is phenotype-dependent. Atherosclerosis, 149, 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K.M., Ernst,M.K., Rice,N.R. and Vousden,K.H. (2000) Role of NF-κB in p53-mediated programmed cell death. Nature, 404, 892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H. and Papaconstantinou,J. (2001) Age-associated differences in cardiovascular inflammatory gene induction during endotoxic stress. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 29307–29312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper W. and Scholz,D. (1997) Growth and remodeling of coronary collateral vessels. In LaFont,A. and Topol,E.J. (eds), Arterial Remodeling: A Critical Factor in Restenosis. Kluwer, Boston, MA, pp. 31–48.

- Scholz D., Ito,W., Fleming,I., Deindl,E., Sauer,A., Wiesnet,M., Busse,R., Schaper,J. and Schaper,W. (2000) Ultastructure and molecular histology of rabbit hind-limb collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis). Virchows Arch., 436, 257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten G.J., Vertegaal,A.C., Whiteside,S.T., Israel,A., Toebes,M., Dorsman,J.C., van der Eb,A.J. and Zantema,A. (1997) IκBα is a target for the mitogen-activated 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase. EMBO J., 16, 3133–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J. et al. (2000) Overexpression of the wild-type p53 gene inhibits NF-κB activity and synergizes with aspirin to induce apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Oncogene, 19, 726–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless N.E. and DePinho,R.A. (2002) p53: Good cop/bad cop. Cell, 110, 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speir E., Modali,R., Huang,E.S., Leon,M.B., Shawl,F., Finkel,T. and Epstein,F. (1994) Potential role of human cytomegalovirus and p53 interaction in coronary restenosis. Science, 265, 391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Fan,H., Honda,T., Fujimaki,R., Lafond-Walker,A., Masui,Y., Lowenstein,C.J. and Becker,L.C. (2001) Activation of NFκB and expression of ICAM-1 in ischemic-reperfused canine myocardium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., 33, 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I. (2001) p53 and atherosclerosis. Circ. Res., 88, 747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa K., Kamijo,R., Ito,D., Hatori,M., Sumitani,K. and Nagumo,M. (1999) Synergistic induction of ICAM-1 expression by cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in a cancer cell line via a NF-κB independent pathway. Br. J. Cancer, 80, 954–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K., Campbell,S.C., Alexander,J.P., Steinbach,F., Edinger,M.G., Tubbs,R.R., Novick,A.C. and Klein,E.A. (1997) Molecular regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) expression in renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Res., 25, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Maruo,A., Fujii,K., Nomi,M., Nakamura,T., Eto,S. and Minami,Y. (2000a) Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 discriminates functionally different populations of human osteoblasts: characteristic involvement of cell cycle regulators. J. Bone Miner. Res., 15, 1912–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y. et al. (2000b) Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 underlies the functional heterogeneity of synovial cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: involvement of cell cycle machinery. Arthritis Rheum., 43, 2513–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner S.D. et al. (2002) p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotype. Nature, 415, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Stolpe A. and van der Saag,P.T. (1996) Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J. Mol. Med., 74, 13–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisard R., Huber,N., Baur,R., Susaa,M., Ickrath,O., Both,A., Koenig,W. and Hombach,V. (2001) Different effects of antisense RelA p65 and NF-8B1 p50 oligonucleotides on the nuclear factor 8B mediated expression of ICAM-1 in human coronary endothelial and smooth muscle cells. BMC Mol. Biol., 2, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadgaonkar R., Phelps,K.M., Haque,Z., Williams,A.J., Silverman,E.S. and Collins,T. (1999) CREB-binding protein is a nuclear integrator of nuclear factor-κB and p53 signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 1879–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanade T. and Fan,J. (1998) Atherosclerotic and inflammation mononuclear cell recruitment and adhesion molecules with reference to the implication of ICAM-1/LFA-1 pathway in atherogenesis. Int. J. Cardiol., 66 (Suppl. 1), S45–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster G.A. and Perkins,N.D. (1999) Transcriptional cross talk between NF-κB and p53. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 3485–3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes F.M., Wamil,B.D., Sun,F., Yan,H.P., Carter,C.E. and Hellerqvist,C.G. (2000) CM101 treatment overrides tumor-induced immunoprivilege leading to apoptosis. Cancer Res., 60, 5740–5746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y. and Gaynor,R.B. (2001) Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Clin. Invest., 107, 135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Verna,L.K., Wang,N.P., Liao,H.L., Ma,K.S., Wang,Y., Zhu,Y. and Stemerman,M.B. (2001) Cholesterol enrichment upregulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1534, 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharatos P.V. et al. (1999) Modulation of wild-type p53 activity by mutant p53 R273H depends on the p53 responsive element (p53RE). A comparative study between the p53REs of the MDM2, WAFI/Cip1 and Bax genes in the lung cancer environment. Anticancer Res., 19, 579–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]