Abstract

The class II transactivator (CIITA) is a master transcriptional regulator of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) promoters. CIITA does not bind DNA, but it interacts with the transcription factors RFX5, NF-Y, and CREB and associated chromatin-modifying enzymes to form an enhanceosome. This report examines the effects of histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC1/HDAC2) on MHC-II gene induction by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and CIITA. The results show that an inhibitor of HDACs, trichostatin A, enhances IFN-γ-induced MHC-II expression, while HDAC1/HDAC2 inhibits IFN-γ- and CIITA-induced MHC-II gene expression. mSin3A, a corepressor of HDAC1/HDAC2, is important for this inhibition, while NcoR, a corepressor of HDAC3, is not. The effect of this inhibition is directed at CIITA, since HDAC1/HDAC2 reduces transactivation by a GAL4-CIITA fusion protein. CIITA binds to overexpressed and endogenous HDAC1, suggesting that HDAC and CIITA may affect each other by direct or indirect association. Inhibition of HDAC activity dramatically increases the association of NF-YB and RFX5 with CIITA, the assembly of CIITA, NF-YB, and RFX5 enhanceosome, and the extent of H3 acetylation at the MHC-II promoter. These results suggest a model where HDAC1/HDAC2 affect the function of CIITA through a disruption of MHC-II enhanceosome and relevant coactivator-transcription factor association and provide evidence that CIITA may act as a molecular switch to modulate MHC-II transcription by coordinating the functions of both histone acetylases and HDACs.

Class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC-II) proteins play a central role in the control of normal immune homeostasis, while aberrant expression of MHC-II is frequently associated with abnormalities in immune responses. MHC-II proteins elicit immune activation through presentation of exogenously derived antigens to CD4+ T cells and represent the seminal control of both peripheral T-cell activation and thymic selection (23, 28, 47). The level of MHC-II expression is exquisitely regulated. Constitutive MHC-II expression is restricted to B cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, whereas inducible expression is observed on a selected number of cell types in response to cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (37, 47). The regulation of MHC-II expression resides predominantly at the transcriptional level and is globally controlled by the master regulator, class II transactivator (CIITA) (12, 47).

CIITA was initially isolated by complementation cloning, using an Epstein-Barr virus-based library to rescue MHC-II expression in MHC-II-negative cells (45). CIITA is encoded by the MHC2TA gene, deletions in which represent the genetic defect in immunodeficient type II group A bare lymphocyte syndrome patients. Expression of CIITA is controlled by four distinct promoters, allowing for a complex pattern of constitutive and inducible MHC-II expression (31, 39). CIITA does not bind DNA but controls MHC-II and related genes by interacting with the requisite MHC-II transcription factors (RFX5, CREB, and NF-Y), which associate with conserved promoter motifs, termed X1, X2, and Y, respectively (9, 26, 29, 42, 58). These interactions are critical for the formation of a stable enhanceosome. CIITA also interacts with components of the basal transcription machinery (TFIIB, TATA binding protein, and TATA binding protein-associated factors) (6, 25, 27). Most relevant to this work, CIITA associates with several chromatin remodeling enzymes, including histone acetyltransferases (HATs) CBP/p300, and pCAF (16, 43, 44, 59), and ATP-dependent remodeling factors, such as BRG-1 (30, 38). These enzymes have all been demonstrated to modulate MHC-II promoter activation.

Structure-function analysis of CIITA protein indicates that it can be divided into three important segments. The N terminus contains an acidic transactivation domain as well as target lysines for both acetylases and a HAT-like domain (16, 40, 44). The mid-section contains a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) that is critical for nuclear import and contributes to self-association (10, 17, 21). The C terminus contains a stretch of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) that are also involved in protein-protein association (11, 21). This unique combination of the NBD and LRR domains is a conserved feature among a new family of known and novel genes, which we have recently called the CATERPILLER family (11). The NBD domain is also shared by a more loosely related family of known genes, called the NACHT family. Members of this family range from plant to mammal proteins with a shared NBD domain and either an LRR motif or a WD40 motif at its C terminus. In addition to these three segments, sequences important for nuclear import controlled by different types of nuclear localization signal (4, 5, 17) are scattered throughout the protein. To a lesser extent, nuclear export sequences have also been found (5, 17).

The molecular mechanism by which CIITA regulates the expression of MHC-II genes is an area of intense interest. CIITA is known to mediate chromatin alterations necessary for promoter accessibility, as demonstrated by in vivo footprinting studies of MHC-II, invariant chain, and HLA-DM promoters in non-B cells (22, 51-53). These studies showed that these promoters are “closed” in the absence of CIITA, with little if any detectable binding by X and Y box binding factors (i.e., RFX or NF-Y). Both IFN-γ and CIITA can induce an open chromatin structure (52, 53). This observation is indicative of chromatin remodeling activity, which could be mediated directly by CIITA or by the recruitment of specific remodeling factors, such as HATs. Interestingly, CIITA also possesses its own intrinsic HAT activity in its N terminus, which may contribute to chromatin remodeling (40). In further support of a role for CIITA in chromatin remodeling, a recent study has reported the correlation of recruitment of CIITA with increased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the endogenous MHC-II promoter (3).

While the role of HATs in CIITA-mediated activation of MHC-II has become more evident, the implication of deacetylation in this process is just emerging. Generally, histone deacetylation correlates with transcriptional repression and is mediated by distinct histone deacetylase (HDAC) complexes (8, 49). The mammalian HDACs identified so far fall into three groups: the yeast RPD3 protein-like HDACs (HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8), the yeast HDA1 protein-like HDACs (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9), and the sirtuin deacetylases, which require NAD as a substrate (8). HDAC1 and HDAC2 are the best characterized of the HDAC proteins. HDAC1 was first isolated by affinity chromatography using the HDAC inhibitor trapoxin (46), whereas HDAC2 was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screening using YY1 transcription factor as bait (54). Both HDAC1 and HDAC2 stably associate with the mSin3A corepressor (2, 34). This complex can be recruited to specific promoters via interactions with an array of sequence-specific transcription factors, including unliganded hormone receptors (RAR and TR) and p53 (15, 32). HDAC1 and HDAC2 are also components of the nucleosome-remodeling HDAC complex, which has been implicated in repression by DNA methylation (35).

A role of HDACs in MHC-II gene control has begun to emerge, although the details have not been delineated. A general HDAC inhibitor (trichostatin A [TSA]) can rescue MHC-II expression in tumor cells and mature dendritic cells where MHC-II transcription is normally repressed (18, 24). Similarly, in a system where MHC-II is inhibited in the absence of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), TSA treatment restored expression, and YY1, a repressor known to interact with HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 (54), was implicated in mediating repression (36). Although these observations suggest a role for HDACs in MHC-II regulation, the part played by specific HDACs is not yet clear.

In this report, we demonstrate that HDAC1 and HDAC2 specifically inhibit the transactivation function of CIITA and the expression of endogenous MHC-II. This inhibition is contingent upon an intact HDAC domain in HDAC1 and is even more profound when mSin3A, an HDAC1-, HDAC2-associated repressor, is present. TSA, a potent inhibitor of HDAC activity, dramatically enhances interactions of CIITA with RFX5 and NF-Y, resulting in substantial increase of transcription. TSA also promotes association of NF-YB and RFX5 with the MHC-II promoter, thereby enhancing recruitment of CIITA. Our findings strongly suggest that Sin3A-associated HDAC1 and HDAC2 are involved in the repression of CIITA-mediated MHC-II transcription through interference with enhanceosome assembly and coactivator (CIITA) interaction with DNA-binding factors (NF-YB and RFX5), providing the basis for a novel mechanism of MHC-II gene regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture cells and conditions.

COS 7, 293T, and HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 5 mM l-glutamine, and streptomycin-penicillin. All cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Plasmids.

The following plasmids have been described previously: Fg-CIITA, Myc-CIITA Fg-RFX5, Fg-NF-YB, DRA300Luc, and Gal5Luc reporter (4, 5, 58). GFP-CIITA was constructed by standard PCR and recombinant DNA methods. Fg-HDAC1, Fg-HDAC2, pIRESHis-mSin3A, and pCEP4-NcoR were kindly provided by A. Baldwin (1). GAL4-CIITA (pSGCIITA) was a gift from Jeremy Boss (41). HDAC1 (H199F) was a kind gift from Ed Seto (15).

Transfection and promoter assays.

COS 7 cells (0.5 × 105 to 1 × 105) were plated in six-well tissue culture plates and then transfected 18 to 24 h later using FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were lysed in 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, Wis.), and luciferase assays were performed as previously described (39).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

COS 7 or 293T cells were plated (1.5 × 106 cells per 100-mm plate) 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with 3 μg of each expression vector using Fugene 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. At 18 to 24 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free; Roche). Samples were lysed for 1 h on ice, centrifuged for 10 min, precleared with 50 μl of goat anti-mouse M-450-conjugated Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway), and immunoprecipitated for 1 h at 4°C with 5 μg of anti-Fg M5 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Immune complexes were isolated with 50 μl of goat anti-mouse M-450 Dynabeads overnight at 4°C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were denatured using Laemmli buffer, and the samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gels were transferred to nitrocellulose and immunoblotted with primary antibody anti-Fg M5 (Sigma) or anti-Myc 9E10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.). Horseradish peroxidase detection was performed using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

ChIP assays.

Chromatin from 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of 0.125 M glycine for 5 min at room temperature. After lysis, the cross-linked chromatin was sheared to an average size of 500 to 1,000 bp by sonication. Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIP) were performed using the ChIP Assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Each chromatin preparation was diluted 1:2, and immunoprecipitation was carried out with 5 μg of anti-Fg M5 or 5 μl of anti-acetyl-histone H3 antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology). In addition, no-antibody control immunoprecipitations were also performed. Cross-links were reversed overnight at 65°C. Analysis of the immunoprecipitated products was done by real-time PCR (see the section below) for the MHC-II promoter or by PCR for the β-actin promoter. In these reactions PCR was carried out for 40 cycles on 1/10 of the immunoprecipitated products, as previously described (36).

Real-time PCR.

cDNA was synthesized as described previously (50). Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). MHC-II probes were labeled at the 5′ end with the reporter dye FAM and at the 3′ end with the quencher dye TAMRA. The 18S rRNA and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probes were labeled at the 5′ end with the reporter dye TET and at the 3′ end with the quencher dye TAMRA. Primer and probe sequences are as follows: MHC-II probe, 5′-6 FAM-CTCCGATCACCAATGTACCTCCAGA-TAMRA-3′; sense primer, 5′-AAGCCAACCTGGAAATCA-3′; antisense primer, 5′-GGCTGTTCGTGAGCACAGTT-3′; GAPDH probe, 5′-6 FAM-CAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAGCC-TAMRA-3′; sense primer, 5′-ACCTCAACTACATGGTTTAC-3′; antisense primer, 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′; 18S rRNA probe, 5′-6 FAM-CAAATTACCCACTCCCGACCCG-TAMRA-3′; sense primer, 5′-GCTGCTGGCACCAGACTT-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGG-3′. Real-time PCR analysis of cDNA specimens was conducted as previously described (50). Values were calculated based on standard curves generated for each gene. Normalization of samples was determined by dividing copies of MHC-II by copies of GAPDH or 18S rRNA.

Real-Time PCR analysis of chromatin-immunoprecipitated products was performed using the following MHC-II promoter primers and probe: MHC-II promoter probe, 5′-6 FAM-CTGGACCCTTTGCAAGAACCCTTCCC-TAMRA-3′; sense primer, 5′-TCCAATGAACGGAGTATCTTGTGT-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-TGAGATGACGCATCTGTTGCT-3′.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescent staining of transiently transfected COS 7 cells was performed as previously described (4). Briefly, 8 × 104 cells were grown overnight and transfected with 1.0 μg of GFP-CIITA and 1.0 μg of HDAC1 or HDAC2 using the FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche). Following fixation with 60% acetone in phosphate-buffered saline, photomicrographs were acquired using Scion Series 7 video capture hardware and an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope.

RESULTS

TSA enhances inducible expression of endogenous MHC-II.

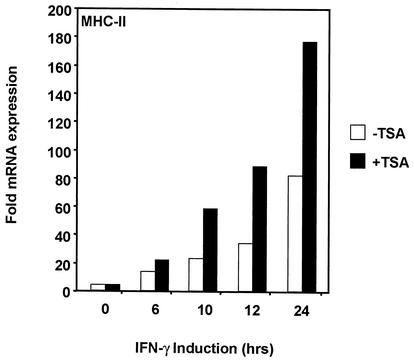

Inhibition of histone deacetylation has been correlated with transcriptional activation (2, 8). Previous reports have shown that TSA, a potent inhibitor of HDAC activity, can rescue MHC-II expression in mouse and human tumor cell lines as well as mature mouse dendritic cells in which MHC-II transcription is normally repressed (18, 24). Similarly, TSA treatment restored expression of MHC-II in a system where the promoter was repressed in the absence of the Rb (36). To address the role of deacetylation in MHC-II gene regulation by IFN-γ, we treated HeLa cells with TSA (100 nM) after IFN-γ induction (500 U/ml) and measured MHC-II mRNA levels by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 1). MHC-II expression was greatly enhanced in the presence of TSA, suggesting that deacetylases are involved in repressing MHC-II. Interestingly, this enhancement occurred over a prolonged time course and was not observed in the absence of IFN-γ (Fig. 1). These results confirm previous findings for a suppressive role of HDACs in MHC-II gene regulation (18, 24, 36).

FIG. 1.

Global inhibition of deacetylation by TSA enhances the inducible expression of MHC-II. Real-time PCR analysis was performed to measure endogenous mRNA levels of MHC-II after IFN-γ induction. HeLa cells were induced with 500 U of IFN-γ/ml for a time course of 24 h and treated with 100 nM TSA. Values represent the averages for three experiments. Samples were normalized to number of GAPDH copies.

HDAC1 and HDAC2 inhibit CIITA transactivation function.

The observation that TSA enhances MHC-II expression led us to hypothesize that HDACs are involved in repressing MHC-II promoters. To identify the specific repressor complexes, the two most abundant deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC2, were tested in a transient-transfection experiment. Cotransfection of either HDAC1 or HDAC2 with CIITA significantly inhibited the activation of an MHC-II reporter (Fig. 2A), suggesting that both HDAC1 and HDAC2 are involved in repressing MHC-II through CIITA. Moreover, this inhibition was blocked by TSA and occurred in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown). To further assess if CIITA is itself a target for HDAC-mediated repression, a Gal4-CIITA construct was used to activate a GAL4 promoter construct. In this system, the GAL4 DNA binding domain within the fusion construct binds to its cognate site on the GAL4 promoter, thus directly recruiting the CIITA fusion partner to the promoter. A cotransfection experiment shows that in the presence of either HDAC1 or HDAC2, CIITA-mediated activation of the Gal4-Luc reporter was significantly repressed (Fig. 2B). To test the specificity of HDACs in this system, we examined the effect of HDAC1 in Gal4-VP16-mediated activation (Fig. 2C). Overexpression of HDAC1 produced little effect on the activation of the Gal4-Luc reporter by Gal4-VP16, indicating that HDAC1 specifically targets Gal4-CIITA.

FIG. 2.

HDAC1 and HDAC2 repress CIITA transactivation function. (A) HDAC1 and HDAC2 repress MHC-II promoter activation. COS 7 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng of CIITA, 1 μg of either HDAC1 or HDAC2, and 0.5 μg of MHC-II-luciferase reporter. Luciferase activity is reported as percent activation relative to that by CIITA alone. (B) HDAC1 and HDAC2 repress a Gal4-CIITA construct. Transfection was performed as described for panel A. (C) Overexpression of HDAC1 does not affect Gal4-VP16 activation. Transfection was performed as described for panel A. Values are shown as mean percent relative luciferase activity ± standard error of the mean for three experiments, each of which was repeated in triplicate. pSG424 is the empty vector control for Gal4 CIITA and Gal4-VP16. (D) HDAC1 or HDAC2 overexpression does not affect CIITA protein levels. Equal amounts of Fg-CIITA and pcDNA3 (top panel, lane 1) or HDAC1 (top panel, lane 2) and HDAC2 (top panel, lane 3) were transfected in COS 7 cells, and Western analysis was performed using anti-Fg antibodies. As a loading control we also immunoblotted with antibodies against actin (bottom panel).

To exclude the possibility that the results of Fig. 2A were due to the suppression of CIITA expression through the activities of HDAC1 and HDAC2, we immunoblotted CIITA-transfected COS 7 cell extracts using antibodies against the Flag (Fg) epitope on CIITA (Fig. 2D). No dramatic change in CIITA expression was found when HDAC1 or HDAC2 were coexpressed (Fig. 2D, compare lane 1 with lanes 2 and 3, respectively). These results strongly suggest that CIITA function, and not its expression, is a direct target of HDAC1 and HDAC2. Furthermore, because in the Gal4 system MHC-II specific transcription factors other than CIITA are not needed, our data argue that repression can also occur in the absence of YY1, which had been previously reported to inhibit inducible expression of MHC-II in Rb-defective tumor cells (36). These results provide evidence for an alternative, YY1-independent mechanism of MHC-II down-regulation.

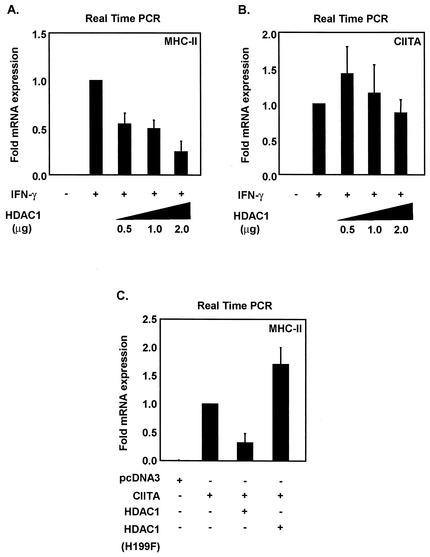

HDAC1 inhibits inducible expression of MHC-II.

Our findings indicate that HDAC1 and HDAC2 inhibit CIITA-mediated activation of an MHC-II reporter. However, the reporter assay system does not entirely reflect physiological chromatin structural constraints. To address the effect of HDACs on endogenous MHC-II, HeLa cells were transfected with increasing dosages of HDAC1 after induction with IFN-γ, and the levels of endogenous MHC-II mRNA were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. HDAC1 significantly inhibited inducible expression of endogenous MHC-II in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the endogenous CIITA transcript remained unaffected by HDAC1, indicating that the reduction of MHC-II expression is not a consequence of reduced CIITA expression (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

HDAC1 specifically represses inducible expression of endogenous MHC-II. (A) Real-time PCR analysis was performed to measure endogenous mRNA levels of MHC-II in the presence of increasing amounts of HDAC1. HeLa cells were induced with IFN-γ (500 U/ml) for 24 h. (B) Overexpression of HDAC1 does not inhibit CIITA mRNA expression. CIITA promoter IV mRNA was measured by real-time PCR. (C) HDAC1 deacetylase activity is required for inhibition of CIITA-mediated activation of endogenous MHC-II. Real-time PCR analysis was performed to measure endogenous mRNA levels of MHC-II in the presence of HDAC1. Equal amounts of CIITA and HDAC1 were transfected into HeLa cells, and mRNA was isolated 24 h posttransfection. An HDAC1 deacetylase-defective mutant (H199F) failed to inhibit MHC-II transcription. Values are means ± standard errors of the means for three experiments. Samples were normalized to the number of 18S rRNA copies.

The possibility exists that HDAC1 is also repressing other components of the IFN-γ signaling pathway. To address this possibility, the requirement for IFN-γ mediators such as STAT1 and IRF-1 was bypassed by the direct introduction of CIITA into HeLa cells. CIITA transfection induced MHC-II transcription as expected, and the cotransfection of HDAC1 greatly inhibited CIITA-mediated activation of endogenous MHC-II as measured by real-time PCR (Fig. 3C). In contrast, an HDAC1 deacetylase-defective mutant (H199F) (14, 15) failed to inhibit MHC-II, indicating that repression of CIITA function by HDAC1 requires an intact deacetylase domain.

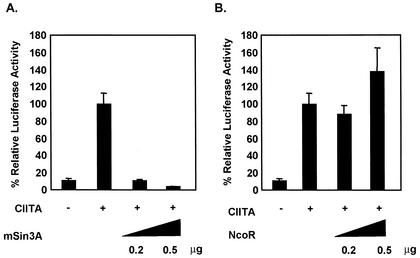

mSin3A is required for MHC-II repression.

HDAC1 and HDAC2 generally exist in stable multicomponent complexes of proteins which are recruited to various promoters through interactions with DNA-binding factors (2, 8). A key component of one such complex is the corepressor, mSin3A, which bridges HDAC with different transcription factors and has been shown to be important for repression mediated by HDAC1 and HDAC2 (2, 8, 13). Although our results indicate that HDAC1 deacetylase activity is required for repression of MHC-II expression (Fig. 3C), a role for mSin3A in this process cannot be excluded. This is a consideration because the deacetylase mutant tested in these experiments (H199F) is also defective in mSin3A binding (13), indicating that this corepressor might also be involved in down-regulating MHC-II gene expression. To test if mSin3A is required for MHC-II repression, we performed transient-transfection assays. Cotransfection of CIITA and increasing amounts of mSin3A completely repressed the activation of an MHC-II reporter (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cotransfection of NcoR, a corepressor known to preferentially associate with HDAC3 (20, 48), did not affect activation of the same reporter (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that mSin3A-associated HDAC1 complexes are required for inhibition of MHC-II expression mediated by CIITA.

FIG. 4.

mSin3A mediates repression of CIITA transactivation function. (A) COS 7 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng of CIITA, increasing amounts of mSin3A, and 0.5 μg of DRA-luciferase reporter. Luciferase activity is reported as percent activation relative to that by CIITA alone. (B) NcoR is not required for repression of MHC-II promoter activity. Transfection was performed as described for panel A. Values are shown as mean percent relative luciferase activity ± standard error of the mean for three experiments, each of which was repeated in triplicate.

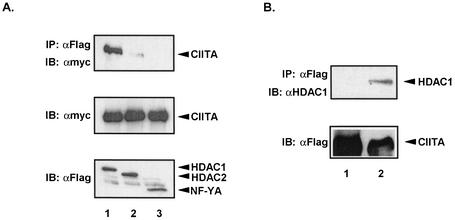

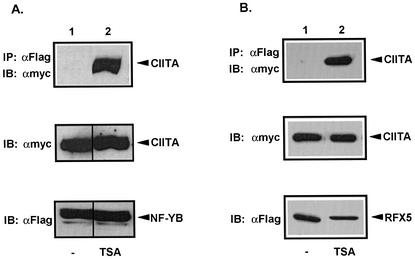

CIITA interacts with both HDAC1 and HDAC2 in vivo.

The results described to this point suggest the possibility that HDAC1 and HDAC2 may interact with CIITA. To test this hypothesis, Myc-CIITA was cotransfected with either Fg-HDAC1 or Fg-HDAC2 in COS 7 cells. HDAC1 or HDAC2 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Fg antibody, and associated CIITA was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. Following immunoblotting, we detected efficient coprecipitation of CIITA with HDAC1 and a much weaker association with HDAC2 (Fig. 5A, upper panel, lanes 1 and 2). To ensure that these interactions are specific for HDAC1 and HDAC2, we also tested another nuclear NF-YA MHC-II enhanceosome-associated protein and observed no detectable association (Fig. 5A, upper panel, lane 3). To assure that no variation in protein expression existed, proteins in the lysates were assayed by immunoblotting prior to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A, lower panels).

FIG. 5.

CIITA associates with HDAC1. (A) Myc-CIITA coimmunoprecipitates with Fg-HDAC1 and Fg-HDAC2. COS 7 cells were transfected with equal amounts of Myc-CIITA and Fg-HDAC1 or Fg-HDAC2. The top panel shows the results for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Fg M5 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc 9E10. CIITA interacted strongly with HDAC1 (lane 1) but only weakly with HDAC2 (lane 2). Association with NF-YA was also tested as a negative control (lane 3). Expression of Myc-CIITA was confirmed in the middle panel, and expression levels of Fg-HDAC1, Fg-HDAC2, and Fg-NF-YA were confirmed in the bottom panels. (B) CIITA coimmunoprecipitates with endogenous HDAC1 in 293T cells. Fg-CIITA was immunoprecipitated from 293T whole-cell lysates with anti-Fg M5 antibody. Endogenous HDAC1 was detected in the top panel (lane 2) by immunoblotting with mouse anti-HDAC1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As a negative control, a bead-only immunoprecipitation was also performed (lane 1). Expression levels of Fg-CIITA were confirmed in the bottom panel.

The above-described experiment relied on an overexpression system of both CIITA and HDAC1 or HDAC2. The endogenous level of CIITA protein is extremely low even in antigen-presenting cells; however, endogenous HDAC1 can be detected by immunoprecipitation (55, 56). We examined the interaction of epitope-tagged CIITA with endogenous HDAC1. To this end, Fg-CIITA from transiently transfected 293T cells was immunoprecipitated with anti-Fg antibody and immunoblotted with antibodies against HDAC1. Endogenous HDAC1 was found to coprecipitate with CIITA (Fig. 5B, upper panel, lane 2), arguing for a physiological role of these interactions in MHC-II gene control. Equal expression of Fg-CIITA was verified by immunoblotting of lysates prior to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5B, lower panel).

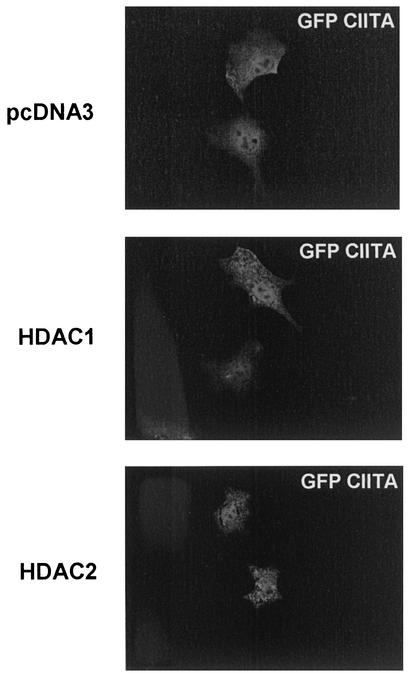

HDAC1 does not affect localization of CIITA.

CIITA localizes to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Nuclear import of CIITA is critical for MHC-II activation and has been shown to be regulated by a number of nuclear localization signals (4, 44). In addition, another study has reported that CIITA can be acetylated by pCAF, thus facilitating its nuclear import (44). Therefore, it is possible that HDAC1 and HDAC2 repress MHC-II by interfering with CIITA localization. To investigate this scenario, we transfected COS 7 cells with GFP-CIITA and examined its localization pattern in the presence of either HDAC1 or HDAC2 (Fig. 6). Expression of either deacetylase did not alter nuclear localization of CIITA. These results indicate that MHC-II repression by HDAC1 and HDAC2 is not likely due to changes in the subcellular distribution of CIITA.

FIG. 6.

Overexpression of HDAC1 or HDAC2 does not change the nuclear localization of CIITA. COS 7 cells were transfected with 1 μg of GFP-CIITA and 3 μg of HDAC1, HDAC2, or empty vector (pcDNA3). Immunofluorescence was detected 24 h posttransfection.

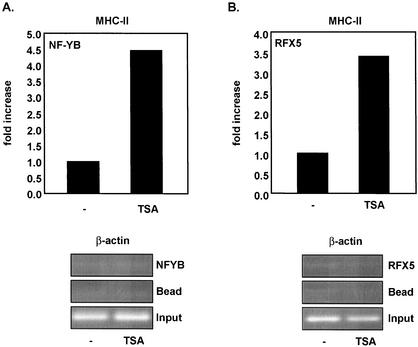

TSA enhances association of CIITA with NF-YB and RFX5.

Several reports have demonstrated extensive protein-protein interactions between CIITA and components of the MHC-II enhanceosome complex, RFX5 and NF-YB/C (26, 42, 58). Because these interactions are critical for MHC-II expression, one could argue that inadequate assembly of this transcription complex mediated by HDAC1 and HDAC2 is inhibitory for efficient promoter activation. To assess the role of HDAC activity in enhanceosome assembly, the interaction of CIITA with RFX5 or NF-YB in vivo was tested in the presence or absence of TSA, a broad inhibitor of HDACs. Myc-CIITA was cotransfected with either Fg-NF-YB or Fg-RFX5 in COS 7 cells. Fg-NF-YB or Fg-RFX5 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Fg antibody, and associated CIITA was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. The general inhibition of deacetylase activity greatly enhanced association of CIITA with both NF-YB (Fig. 7A, upper panel, compare lanes 1 and 2) and RFX5 (Fig. 7B, upper panel, compare lanes 1 and 2). Equal expression of CIITA, NF-YB, and RFX5 was verified by immunoblotting of lysates prior to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 7A and B, lower panels). These results strongly suggest that HDAC activity inhibits critical interactions of CIITA with MHC-II DNA-binding factors.

FIG. 7.

TSA promotes association of CIITA with NF-YB and RFX5. (A) TSA enhances interaction of CIITA with NF-YB (compare lanes 1 and 2). COS 7 cells were transfected with equal amounts of Myc-CIITA and Fg-NF-YB and treated with 300 nM TSA. The top panel shows the results for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Fg M5 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc 9E10. Expression of Myc-CIITA in lysates was confirmed in the middle panel, whereas expression levels of Fg-NF-YB in lysates were confirmed in the bottom panel. (B) TSA enhances interaction of CIITA with RFX5 (compare lanes 1 and 2). Expression and detection of Myc-CIITA interaction with Fg-RFX5 was performed using the same procedure as described for panel A. Expression levels of Myc-CIITA and Fg-RFX5 were confirmed in the middle and bottom panels, respectively.

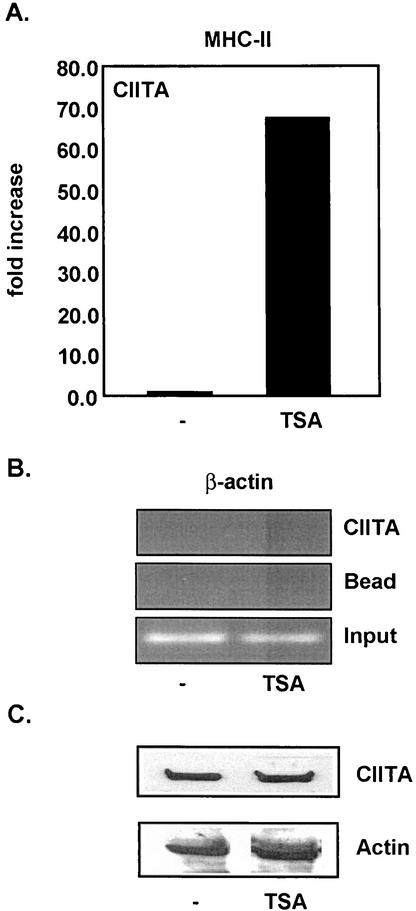

TSA promotes the stable association of CIITA and MHC-II enhanceosome factors with the endogenous MHC-II promoter.

Extensive biochemical studies have demonstrated that MHC-II transcription factors are involved in multiple protein-protein interactions that are critical for CIITA recruitment and promoter activation (26, 42, 58). Because TSA promotes the association of CIITA with RFX5 and NF-YB (Fig. 7), we predicted that enhanced recruitment of CIITA to the MHC-II promoter would be facilitated by TSA treatment as well. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of TSA on the association of CIITA with the MHC-II promoter by ChIP analysis. Fg-tagged CIITA was transiently transfected into 293T cells, and immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-Fg antibodies. DNA isolated from immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by real-time PCR. ChIP analysis demonstrated that TSA greatly increased CIITA association with the MHC-II promoter (Fig. 8A), suggesting that the inhibition of HDAC activity is important for CIITA recruitment to the promoter. To ensure that the TSA effect specifically occurs at CIITA-dependent promoters, we performed PCR analysis on the immunoprecipitated DNA with primers for the β-actin promoter. CIITA did not interact with the β-actin promoter in the presence of TSA (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, to exclude the possibility that the enhanced association of CIITA with the promoter was simply a result of elevated CIITA protein levels in the presence of TSA, we immunoblotted transfected 293T cell extracts using antibodies against the Fg epitope on CIITA and found that CIITA expression was not altered by TSA (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

(A) TSA enhances CIITA recruitment to the MHC-II promoter. 293T cells were transfected with Fg-CIITA and treated with 300 nM TSA. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-Fg M5. MHC-II promoter DNA was detected by quantitative real-time PCR. Data are presented as increases compared to results with untreated cells. Real-time PCR values were determined by subtracting values obtained from bead-only immunoprecipitations and normalizing to the total amount of MHC-II promoter DNA added to the immunoprecipitation reaction (input). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) TSA does not promote association of CIITA with the β-actin promoter. Chromatin was prepared from transiently transfected 293T cells as was done for panel A. PCR was performed to detect β-actin promoter DNA sequences. Input represents 1% of the total chromatin introduced into each immunoprecipitation reaction. (C) TSA does not affect CIITA protein levels. 293T cells were transfected with Fg-CIITA and treated with TSA as for panel A. CIITA was detected by Western analysis anti-Fg antibody. As a loading control we also immunoblotted with antibodies against actin (bottom panel).

As previously mentioned, CIITA is recruited to MHC-II promoters via multiple interactions with components of the MHC-II enhanceosome. One mechanism by which TSA enhances CIITA recruitment to the MHC-II promoter could involve increasing enhanceosome complex assembly at the promoter. To test this hypothesis, we transfected 293T cells with Fg-NF-YB or Fg-RFX5, treated the cells with TSA, and performed ChIP assays (Fig. 9). Our results indicate that TSA enhanced the binding of both NF-YB (Fig. 9A) and RFX5 (Fig. 9B) to the MHC-II promoter, without affecting the level of their expression (data not shown). It should be noted that the fold increase in association of NF-YB and RFX5 with the promoter is less pronounced (Fig. 9) than that of CIITA (Fig. 8A). As controls, TSA did not enhance association of NF-YB or RFX5 with the β-actin promoter (Fig. 9, bottom panels). This finding is consistent with those of previous studies demonstrating that multiple interactions of CIITA with MHC-II DNA-binding factors have a synergistic effect on recruitment of CIITA to MHC-II promoters (26) but additionally shows that TSA enhances these interactions at the promoter.

FIG. 9.

TSA promotes a stable association of RFX5 and NF-YB with the MHC-II promoter. (A) TSA enhances NF-YB association with the MHC-II promoter (top panel) but not the β-actin promoter (bottom panel). 293T cells were transiently transfected with Fg-NF-YB and treated with TSA (300 nM). Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-Fg M5. MHC-II promoter sequences were detected by quantitative real-time PCR, and β-actin promoter was detected by PCR. Data are presented as increases compared to results with untreated cells. Real-time PCR values were determined by subtracting values obtained from bead-only immunoprecipitations and normalizing to the total amount of MHC-II promoter DNA added to the immunoprecipitation reaction (Input). (B) TSA enhances RFX5 association with the MHC-II promoter (top panel). 293T cells were transfected with Fg-RFX5 and treated with TSA as described for panel A. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as for panel A. Real-time PCR values were determined as for panel A. Association of RFX5 with the β-actin promoter was not detected (bottom panel).

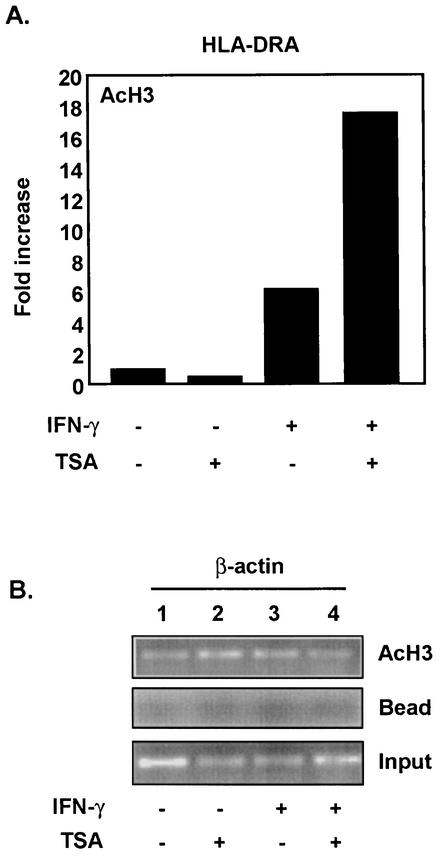

TSA enhances IFN-γ-dependent H3 acetylation at the MHC-II promoter.

A majority of the above-described experiments utilized overexpressed CIITA. To further explore the effect of TSA and HDACs on MHC-II promoters in a physiologic setting, we reexamined the IFN-γ induction of MHC-II. Hyperacetylation of lysines in the NH2-terminal tails of core histones has been strongly correlated with active genes and has been shown to be required for an “open” chromatin conformation, facilitating promoter association of transcription factors (33) Analogously, hypoacetylation at specific promoters has been correlated with recruitment of HDAC complexes to repressed genes (33). Our findings indicate that blocking of HDAC activity by TSA enhances IFN-γ-inducible expression of endogenous MHC-II (Fig. 1). An additional mechanism by which TSA increases MHC-II expression could involve decreasing the ratio of HDAC-to-HAT activities, thus causing enhanced acetylation levels of histone H3. To test this possibility, we induced HeLa cells with IFN-γ (500 U/ml), treated these cells with TSA (100 nM), and performed ChIP assays using anti-acetyl H3 antibodies. As predicted from a previous report (3), IFN-γ induced a fivefold increase in H3 acetylation at the MHC-II promoter (Fig. 10A). Significantly, TSA further enhanced IFN-γ-dependent acetylation of H3 (Fig. 10A) at the promoter region. These experiments support the model where IFN-γ increases histone acetylation and also indicate that IFN-γ cannot completely remove all residual HDAC activity from the promoter. Instead, TSA is necessary to inhibit all HDAC activity, leading to a further enhancement of histone acetylation and gene expression. The acetylation level of histone H3 at the β-actin promoter did not change in response to IFN-γ, again indicating the specificity of these results (Fig. 10B). These data indicate that the induction of MHC-II by IFN-γ is modulated by HDAC activity.

FIG. 10.

(A) TSA enhances IFN-γ-dependent acetylation of histone H3 (AcH3) at the MHC-II promoter. HeLa cells were induced with IFN-γ (500 U/ml) for 24 h and treated with 100 nM TSA. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-acetyl H3. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR, and values were determined as described in the legend for Fig. 8A. (B) IFN-γ does not affect H3 acetylation at the β-actin promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as for panel A, and DNA was analyzed by PCR. Input represents 1% of the total chromatin introduced into each immunoprecipitation reaction.

DISCUSSION

Precise control of MHC-II expression ensures appropriate responses to pathogens while minimizing collateral damage to host tissue. The regulation of MHC-II genes resides predominantly at the level of transcription and is controlled by the class II transactivator, CIITA. Multiple interactions of CIITA with site-specific DNA-binding factors, components of the basal transcription machinery, and chromatin modifiers have been shown to play a critical role in MHC-II activation (47). In addition, a key report has demonstrated the role of histone acetylation in MHC-II regulation (3). However, far less is known about the chromatin complexes that are involved in repression of MHC-II. This work shows that HDACs are key players in the control of MHC-II transcription, CIITA function, and association with other transcription factors in lysates and on promoters.

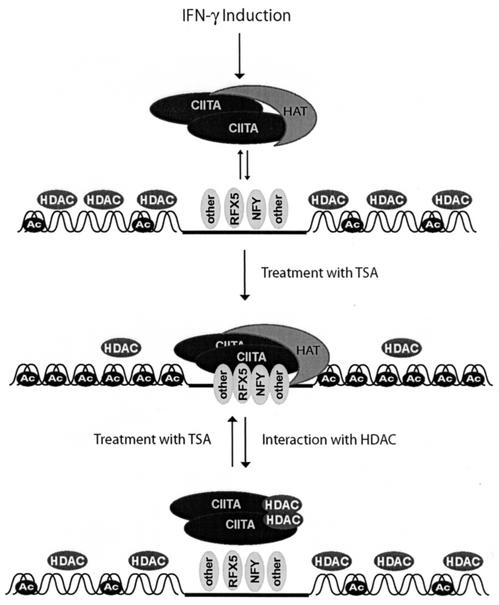

Previous observations led us to hypothesize that HDACs might be involved in inhibition of MHC-II (24, 36). This study examined the role of HDACs, specifically HDAC1 and HDAC2, in MHC-II gene regulation. We demonstrated that HDACs inhibit IFN-γ activation of MHC-II by inhibiting the transactivation function of CIITA. This inhibition requires an intact HDAC1 deacetylase domain and can also be mediated by the corepressor mSin3A. Furthermore, CIITA associated with both exogenous and endogenous HDAC1, indicating that direct or indirect CIITA-HDAC interactions may occur. Finally, inhibition of HDAC activity by TSA dramatically enhances the interaction of CIITA with NF-YB and RFX5 and has a profound effect on the recruitment of CIITA to the endogenous MHC-II promoter. These results suggest that HDAC1 may be recruited to the MHC-II promoter to cause gene repression via the disruption of MHC-II enhanceosome formation (Fig. 11).

FIG. 11.

Model for the role of HDACs in MHC-II regulation. In the absence of inducing signals, such as IFN-γ signals, histones are hypoacetylated at the MHC-II promoter due to the presence of HDAC and absence of HAT activity. Association of MHC-II DNA-binding factors with the MHC-II promoter is observed at a low level. When CIITA is induced by IFN-γ, it associates with MHC-II transcription factors, such as RFX5 and NF-YB, and HATs. These interactions open chromatin and correlate with increased acetylated H3. If HDAC activity is inhibited by TSA, CIITA-NF-YB-RFX5 interactions are further stabilized and MHC-II enhanceosome formation is enhanced. Histones also become hyperacetylated, and maximal activation is achieved. At the end of the induction phase, HDAC may interact with CIITA, resulting in the disassembly of the entire enhanceosome complex.

Many possible scenarios could explain the observation that blocking HDAC activity enhances the formation of the CIITA-NF-YB-RFX5 complex. Both CIITA (44) and NF-Y (19) are known substrates of HDACs. Treatment with TSA could increase acetylation of CIITA and/or NF-Y, promoting their association and interaction with the MHC-II promoter. Conversely, it is possible that HDAC1 and/or HDAC2 directly targets CIITA or NF-Y for deacetylation and affect their interaction potential or ability to bind DNA. Acetylation of RFX5 is also possible; however, this has not been tested. In agreement with this hypothesis, we demonstrated that inhibition of deacetylase activity by TSA promotes the ability of both NF-YB and RFX5 to associate with the MHC-II promoter. However, the order of events is not clear from our data: enhanced recruitment of NF-YB and RFX5 may promote CIITA recruitment; alternatively, enhanced CIITA may stabilize the NF-YB-RFX5 complex. Recent reports have demonstrated that HDAC1 deacetylates nonhistone proteins, such as p53, which inhibits its transactivation function (32).

Another possibility is that HDAC1 and HDAC2 disrupt MHC-II enhanceosome formation by removing CIITA from the transcription complex. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that CIITA interacts with HDAC1 in vivo, although it is currently unclear whether this association is direct or mediated by other repressors, such as mSin3A. Our data show a more pronounced effect of mSin3A than HDAC1 or HDAC2 on MHC-II repression. This implies that HDAC1 may indirectly affect CIITA function via its binding to mSin3A. Significantly, NcoR, which is preferentially assembled into HDAC3 complexes, failed to repress MHC-II, suggesting that CIITA specifically associates with HDAC1. As an alternate scenario, it is plausible that HDAC1 and HDAC2 or other HDACs interact with NF-YB and RFX5, thus altering their functional activity or association with CIITA. However, we have failed to detect an association between HDAC1/HDAC2 and NF-YB or RFX5 (data not shown), indicating that this is a less likely possibility.

An additional mechanism by which HDAC1 and HDAC2 mediate MHC-II repression could involve the deacetylation of histones at the promoter. The primary activity of HDAC1 and HDAC2 is to deacetylate histones H3 and H4, providing the basis for transcriptional repression of genes (49). Our results demonstrate that HDAC1 and HDAC2 significantly inhibit CIITA-mediated activation of MHC-II; presumably this can occur via recruitment of HDAC1 and HDAC2 repressor complexes to the promoter. Although the association of either HDAC1 or HDAC2 with the MHC-II promoter has not yet been demonstrated, it is likely that these enzymes deacetylate histones H3 and H4 at specific regions of the MHC-II promoter, thus disrupting transcription factor association and inhibiting gene expression. Our data further demonstrates that broad inhibition of HDAC activity by TSA additionally enhanced H3 acetylation at the endogenous MHC-II promoter after IFN-γ induction. This suggests that HDAC is present at the MHC-II promoter and that even under strong cytokine induction, the promoter still retains some associated HDAC activity. Whether CIITA recruits HDAC activity to MHC-II promoters remains to be explored. Furthermore, alternative mechanisms of CIITA-independent HDAC recruitment cannot be excluded. One such mechanism could involve YY1-mediated repression (36) and could explain the up-regulation of MHC-II expression observed in CIITA-negative cells in the presence of TSA (24).

One caveat with many of the above scenarios is that the hypothesis is driven by the inhibition of CIITA function by HDACs. However, it is likely that bidirectional effects are occurring, and CIITA also affects the function of HDACs. For example, the interaction of HDAC1 with CIITA may well cause a reversed outcome, where CIITA removes HDAC1 from the promoter, allowing histones to be acetylated and the promoter to be open. This then allows more stable formation of the NF-YB-RFX5 enhanceosome complex which is further enhanced by interaction with CIITA.

One important observation is that CIITA can associate with both HATs (CBP/p300, pCAF) (7, 16, 43, 44, 59) and HDACs (HDAC1 and HDAC2) (this study), suggesting that CIITA might act as a molecular switch, central to these two opposing states of MHC-II transcription. That CIITA may serve as a mediator that leads to the eventual extinction of MHC-II gene transcription after the initial stage of gene activation is accomplished is an unorthodox possibility. If this is the case, it is possible that different posttranslational modifications in CIITA modulate its association with either activator or repressor complexes. In support of this model, it has recently been demonstrated that phosphorylation of the p65 NF-κB subunit determines whether it associates with CBP or HDAC1, ensuring proper regulation of p65-dependent genes (57).

In summary, our results show that HDAC1 and HDAC2 suppress activation of an MHC-II reporter construct and the endogenous MHC-II promoter by both IFN-γ and CIITA (Fig. 11). The specific involvement of HDAC1 and HDAC2 is demonstrated here, although other HDACs are likely involved but have not yet been examined. The balance of HDAC and HAT activities likely determines the extent of enhanceosome formation involving CIITA, NF-YB, and RFX5. Interestingly, even in the presence of a strong cytokine inducer such as IFN-γ, a basal level of HDACs still appears to be exerting its effect on the MHC-II promoter in terms of both gene induction and histone acetylation. These results suggest that CIITA may be a central molecular switch for MHC class II gene regulation through its interactions with both HATs and HDACs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for their generous assistance: A. Baldwin for providing pcDNA3-HDAC1, mSin3A, and NcoR; E. Seto for the gift of HDAC2 and HDAC1 (H199F); J. M. Boss for providing Gal4-CIITA; A. Wong for assistance with real-time PCR; and J. Brickey for careful review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grants 29564, 45580, and 41751 (to J.P.-Y.T.) and a National Multiple Sclerosis Society postdoctoral fellowship (to S.F.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashburner, B. P., S. D. Westerheide, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 2001. The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-êB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7065-7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ayer, D. E. 1999. Histone deacetylases: transcriptional repression with SINers and NuRDs. Trends Cell Biol. 9:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beresford, G. W., and J. M. Boss. 2001. CIITA coordinates multiple histone acetylation modifications at the HLA-DRA promoter. Nat. Immunol. 2:652-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cressman, D. E., K. C. Chin, D. J. Taxman, and J. P. Ting. 1999. A defect in the nuclear translocation of CIITA causes a form of type II bare lymphocyte syndrome. Immunity 10:163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cressman, D. E., W. J. O'Connor, S. F. Greer, X. S. Zhu, and J. P. Ting. 2001. Mechanisms of nuclear import and export that control the subcellular localization of class II transactivator. J. Immunol. 167:3626-3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontes, J. D., B. Jiang, and B. M. Peterlin. 1997. The class II trans-activator CIITA interacts with the TBP-associated factor TAFII32. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2522-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontes, J. D., S. Kanazawa, D. Jean, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Interactions between the class II transactivator and CREB binding protein increase transcription of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:941-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grozinger, C. M., and S. L. Schreiber. 2002. Deacetylase enzymes: biological functions and the use of small-molecule inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 9:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hake, S. B., K. Masternak, C. Kammerbauer, C. Janzen, W. Reith, and V. Steimle. 2000. CIITA leucine-rich repeats control nuclear localization, in vivo recruitment to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II enhanceosome, and MHC class II gene transactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7716-7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harton, J. A., D. E. Cressman, K. C. Chin, C. J. Der, and J. P. Ting. 1999. GTP binding by class II transactivator: role in nuclear import. Science 285:1402-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harton, J. A., M. W. Linhoff, J. Zhang, and J. P. Ting. 2002. CATERPILLER: a large family of mammalian genes containing CARD, Pyrin, nucleotide binding and leucine-rich repeat domains. J. Immunol. 169:4088-4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harton, J. A., and J. P. Ting. 2000. Class II transactivator: mastering the art of major histocompatibility complex expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6185-6194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassig, C. A., T. C. Fleischer, A. N. Billin, S. L. Schreiber, and D. E. Ayer. 1997. Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A. Cell 89:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassig, C. A., J. K. Tong, T. C. Fleischer, T. Owa, P. G. Grable, D. E. Ayer, and S. L. Schreiber. 1998. A role for histone deacetylase activity in HDAC1-mediated transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3519-3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juan, L. J., W. J. Shia, M. H. Chen, W. M. Yang, E. Seto, Y. S. Lin, and C. W. Wu. 2000. Histone deacetylases specifically down-regulate p53-dependent gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20436-20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kretsovali, A., T. Agalioti, C. Spilianakis, E. Tzortzakaki, M. Merika, and J. Papamatheakis. 1998. Involvement of CREB binding protein in expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes via interaction with the class II transactivator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6777-6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kretsovali, A., C. Spilianakis, A. Dimakopoulos, T. Makatounakis, and J. Papamatheakis. 2001. Self-association of class II transactivator correlates with its intracellular localization and transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32191-32197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landmann, S., A. Muhlethaler-Mottet, L. Bernasconi, T. Suter, J. M. Waldburger, K. Masternak, J. F. Arrighi, C. Hauser, A. Fontana, and W. Reith. 2001. Maturation of dendritic cells is accompanied by rapid transcriptional silencing of class II transactivator (CIITA) expression. J. Exp. Med. 194:379-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, L. F., G. Li, D. J. Templeton, and J. P. Ting. 1998. Paclitaxel (Taxol)-induced gene expression and cell death are both mediated by the activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK/SAPK). J. Biol. Chem. 273:28253-28260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, J., J. Wang, Z. Nawaz, J. M. Liu, J. Qin, and J. Wong. 2000. Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. EMBO J. 19:4342-4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linhoff, M. W., J. A. Harton, D. E. Cressman, B. K. Martin, and J. P. Ting. 2001. Two distinct domains within CIITA mediate self-association: involvement of the GTP-binding and leucine-rich repeat domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3001-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linhoff, M. W., K. L. Wright, and J. P. Ting. 1997. CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y and RFX are required for in vivo assembly of a nucleoprotein complex that spans 250 base pairs: the invariant chain promoter as a model. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4589-4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mach, B., V. Steimle, E. Martinez-Soria, and W. Reith. 1996. Regulation of MHC class II genes: lessons from a disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14:301-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magner, W. J., A. L. Kazim, C. Stewart, M. A. Romano, G. Catalano, C. Grande, N. Keiser, F. Santaniello, and T. B. Tomasi. 2000. Activation of MHC class I, II, and CD40 gene expression by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Immunol. 165:7017-7024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahanta, S. K., T. Scholl, F. C. Yang, and J. L. Strominger. 1997. Transactivation by CIITA, the type II bare lymphocyte syndrome-associated factor, requires participation of multiple regions of the TATA box binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6324-6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masternak, K., A. Muhlethaler-Mottet, J. Villard, M. Zufferey, V. Steimle, and W. Reith. 2000. CIITA is a transcriptional coactivator that is recruited to MHC class II promoters by multiple synergistic interactions with an enhanceosome complex. Genes Dev. 14:1156-1166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masternak, K., and W. Reith. 2002. Promoter-specific functions of CIITA and the MHC class II enhanceosome in transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 21:1379-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDevitt, H. O. 1998. The role of MHC class II molecules in susceptibility and resistance to autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10:677-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno, C. S., G. W. Beresford, P. Louis-Plence, A. C. Morris, and J. M. Boss. 1999. CREB regulates MHC class II expression in a CIITA-dependent manner. Immunity 10:143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudhasani, R., and J. D. Fontes. 2002. The class II transactivator requires brahma-related gene 1 to activate transcription of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5019-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhlethaler-Mottet, A., L. A. Otten, V. Steimle, and B. Mach. 1997. Expression of MHC class II molecules in different cellular and functional compartments is controlled by differential usage of multiple promoters of the transactivator CIITA. EMBO J. 16:2851-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy, M., J. Ahn, K. K. Walker, W. H. Hoffman, R. M. Evans, A. J. Levine, and D. L. George. 1999. Transcriptional repression by wild-type p53 utilizes histone deacetylases, mediated by interaction with mSin3a. Genes Dev. 13:2490-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narlikar, G. J., H. Y. Fan, and R. E. Kingston. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng, H. H., and A. Bird. 2000. Histone deacetylases: silencers for hire. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng, H. H., Y. Zhang, B. Hendrich, C. A. Johnson, B. M. Turner, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, D. Reinberg, and A. Bird. 1999. MBD2 is a transcriptional repressor belonging to the MeCP1 histone deacetylase complex. Nat. Genet. 23:58-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osborne, A., H. Zhang, W. M. Yang, E. Seto, and G. Blanck. 2001. Histone deacetylase activity represses gamma interferon-inducible HLA-DR gene expression following the establishment of a DNase I-hypersensitive chromatin conformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6495-6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panek, R. B., Y. J. Lee, Y. Itoh-Lindstrom, J. P. Ting, and E. N. Benveniste. 1994. Characterization of astrocyte nuclear proteins involved in IFN-gamma- and TNF-alpha-mediated class II MHC gene expression. J. Immunol. 153:4555-4564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattenden, S. G., R. Klose, E. Karaskov, and R. Bremner. 2002. Interferon-gamma-induced chromatin remodeling at the CIITA locus is BRG1 dependent. EMBO J. 21:1978-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piskurich, J. F., M. W. Linhoff, Y. Wang, and J. P. Ting. 1999. Two distinct gamma interferon-inducible promoters of the major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator gene are differentially regulated by STAT1, interferon regulatory factor 1, and transforming growth factor beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:431-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raval, A., T. K. Howcroft, J. D. Weissman, S. Kirshner, X. S. Zhu, K. Yokoyama, J. Ting, and D. S. Singer. 2001. Transcriptional coactivator, CIITA, is an acetyltransferase that bypasses a promoter requirement for TAF(II)250. Mol. Cell 7:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley, J. L., S. D. Westerheide, J. A. Price, J. A. Brown, and J. M. Boss. 1995. Activation of class II MHC genes requires both the X box region and the class II transactivator (CIITA). Immunity 2:533-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholl, T., S. K. Mahanta, and J. L. Strominger. 1997. Specific complex formation between the type II bare lymphocyte syndrome-associated transactivators CIITA and RFX5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6330-6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sisk, T. J., T. Gourley, S. Roys, and C. H. Chang. 2000. MHC class II transactivator inhibits IL-4 gene transcription by competing with NF-AT to bind the coactivator CREB binding protein (CBP)/p300. J. Immunol. 165:2511-2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spilianakis, C., J. Papamatheakis, and A. Kretsovali. 2000. Acetylation by PCAF enhances CIITA nuclear accumulation and transactivation of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8489-8498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steimle, V., L. A. Otten, M. Zufferey, and B. Mach. 1993. Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or bare lymphocyte syndrome). Cell 75:135-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taunton, J., C. A. Hassig, and S. L. Schreiber. 1996. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science 272:408-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ting, J. P., and J. Trowsdale. 2002. Genetic control of MHC class II expression. Cell 109(Suppl.):S21-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen, Y. D., V. Perissi, L. M. Staszewski, W. M. Yang, A. Krones, C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, and E. Seto. 2000. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor corepressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7202-7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolffe, A. P. 1996. Histone deacetylase: a regulator of transcription. Science 272:371-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong, A., N. Ghosh, K. P. McKinnon, W. Reed, J. F. Piskurich, K. L. Wright, and J. P. Ting. 2002. Regulation and specificity of MHC2TA promoter usage in T lymphocytes and cell line. J. Immunol. 169:3112-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wright, K. L., K. C. Chin, M. Linhoff, C. Skinner, J. A. Brown, J. M. Boss, G. R. Stark, and J. P. Ting. 1998. CIITA stimulation of transcription factor binding to major histocompatibility complex class II and associated promoters in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6267-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright, K. L., T. L. Moore, B. J. Vilen, A. M. Brown, and J. P. Ting. 1995. Major histocompatibility complex class II-associated invariant chain gene expression is up-regulated by cooperative interactions of Sp1 and NF-Y. J. Biol. Chem. 270:20978-20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright, K. L., and J. P. Ting. 1992. In vivo footprint analysis of the HLA-DRA gene promoter: cell-specific interaction at the octamer site and up-regulation of X box binding by interferon gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7601-7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, W. M., Y. L. Yao, J. M. Sun, J. R. Davie, and E. Seto. 1997. Isolation and characterization of cDNAs corresponding to an additional member of the human histone deacetylase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28001-28007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang, Y., G. LeRoy, H. P. Seelig, W. S. Lane, and D. Reinberg. 1998. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell 95:279-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, Y., H. H. Ng, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, A. Bird, and D. Reinberg. 1999. Analysis of the NuRD subunits reveals a histone deacetylase core complex and a connection with DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 13:1924-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhong, H., M. J. May, E. Jimi, and S. Ghosh. 2002. The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF-kappa B determines its association with CBP/p300 or HDAC-1. Mol. Cell 9:625-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu, X. S., M. W. Linhoff, G. Li, K. C. Chin, S. N. Maity, and J. P. Ting. 2000. Transcriptional scaffold: CIITA interacts with NF-Y, RFX, and CREB to cause stereospecific regulation of the class II major histocompatibility complex promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6051-6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu, X. S., and J. P. Ting. 2001. A 36-amino-acid region of CIITA is an effective inhibitor of CBP: novel mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated suppression of collagen α2(I) and other promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7078-7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]