Abstract

A characteristic feature of malaria during pregnancy is the sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells (IRBCs) in the intervillous spaces of the placenta. We have recently shown that unusually low-sulfated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) present in the intervillous spaces mediate the adherence of IRBCs in the placenta. In areas of endemicity, the prevalence of P. falciparum infection in pregnant women peaks during weeks 13 to 20 and then gradually declines, implying that the placental CSPGs are available for IRBC adhesion early during the pregnancy. However, there is no information on the expression and composition of CSPGs during pregnancy. In this study, the expression pattern of CSPGs during the course of pregnancy was investigated. The CSPGs were purified from placentas of various gestational ages, characterized, and tested for the ability to bind IRBCs. The data demonstrate that the CSPGs are present in the intervillous spaces throughout the second and third trimesters. The levels of CSPGs expressed per unit tissue weight were similar in placentas of various gestational ages. However, the structures of the intervillous-space CSPGs changed considerably during the course of pregnancy. In particular, the molecular weight was decreased, with an accompanying gradual increase in the CSPG size polydispersity, from 16 weeks until 38 weeks. The sulfate content was increased considerably after 24 weeks. Despite these structural changes, the CSPGs of placentas of various gestational ages efficiently supported the binding of IRBCs. These results demonstrate that CSPGs can mediate the sequestration of IRBCs in the intervillous spaces of the placenta during the entire second and third trimesters and possibly during the later part of the first trimester as well.

Malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum is a major health problem in many parts of the world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (16, 29, 37, 39). In areas where malaria is endemic, children under 5 years of age are the most vulnerable group for developing severe disease. In Africa alone, an estimated 1 to 3 million children die from malaria every year (29, 37). Individuals who successfully survive P. falciparum malaria episodes in childhood develop natural immunity against the parasite, and by adolescence they are more or less protected from severe malaria illness (4, 35). However, women, despite the presence of acquired protective immunity, are likely to develop severe anemia and clinical disease during pregnancy (27-30). The risk of malaria in pregnant women is highest for primigravidas and decreases with increasing gravidity (7, 27). This is likely due to the development of protective immune responses, specifically to parasites that selectively bind in the placenta (11-13, 24, 25, 29, 30, 32-36).

Of the four species of malaria parasites that can infect humans, P. falciparum accounts for the majority of the deaths due to malaria. A distinct characteristic feature of P. falciparum compared to the other three parasite species is its ability to express adherent proteins on the surface of infected red blood cells (IRBCs). Adhesion molecules enable IRBCs to adhere in the microvascular capillaries of vital organs, causing organ dysfunction and severe pathological conditions (26-29). The adhesion of IRBCs appears to be mediated by a family of antigenic var gene proteins (8, 14, 29, 31, 33, 36, 40). These proteins, exhibiting divergent adhesion properties, enable IRBCs to bind to several cell adhesion molecules expressed on vascular endothelial cells (5, 14, 15). Because over a period of time the host develops adhesion-specific immunity, the parasite constantly switches to variable adherent phenotypes to survive (6). It is thought that individuals develop immunity against the whole spectrum of divergent parasite phenotypes by adulthood (4, 35). Therefore, adults in areas of endemicity are able to control parasite growth and rarely develop pathological conditions despite constantly harboring parasites.

The situation drastically changes in women during pregnancy, due in part to the availability of new IRBC adhesion receptors in the placenta. This leads to the selection of a distinct parasite phenotype that grows efficiently in the placental environment. Accumulation of IRBCs in the placenta and consequent infiltration of macrophages may lead to severe malaria in the mother and a poor pregnancy outcome (7, 22, 26, 28-30, 39).

Chondroitin-4-sulfate (C4S) has been shown to be the primary receptor for IRBC adhesion in the human placenta (2, 11, 17, 18, 24, 25, 36). A previous study, based on detailed biochemical characterization and IRBC binding characteristics of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) purified from full-term placentas, demonstrated that unusually low-sulfated, extracellular CSPGs present in the intervillous spaces mediate IRBC adhesion (2). This is consistent with the observations that in the placenta, IRBCs sequester predominantly in the intervillous spaces, although some adhere to syncytiotrophoblasts (30, 42, 43). In pregnant women, the prevalence of parasite infection is highest between 13 and 20 weeks of gestation (7, 45), which likely corresponds to the period when IRBCs accumulate in high numbers in the placenta. Thus, for the CSPGs to be the relevant receptor for IRBC binding in the placenta, these molecules must be expressed in the intervillous spaces in significant amounts at the end of the first trimester and the beginning of the second trimester. However, whether CSPGs are present in the intervillous spaces of the placenta during these periods of pregnancy has not been investigated. In the present study, we purified the CSPGs of the intervillous spaces from placentas of various gestational ages, biochemically characterized them, and tested for their ability to bind IRBCs. The data show that CSPGs are expressed in the intervillous spaces throughout the second and third trimesters. The placental CSPGs exhibit considerable change with regard to size, polydispersity, and degree of sulfation as a function of gestational age. However, despite these changes, the placental CSPGs from all gestational ages were able to efficiently bind IRBCs. Thus, the data presented here establish, for the first time, the availability of CSPGs for IRBC adherence in the placenta during the entire period of the second and third trimesters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Proteus vulgaris chondroitinase ABC, Arthrobacter aurescens chondroitinase AC II (87 U/mg), Flavobacterium heparinum chondroitinase B (25 U/mg), F. heparinum heparitinase (113 U/mg), and Streptomyces hyalurolyticus hyaluronidase (2,000 turbidity-reducing units/mg) were purchased from Seikagaku America (Falmouth, Mass.). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, N-ethylmaleimide, benzamidine, and protein molecular weight standards for gel filtration were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). N-α-Tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK), and N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) were from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.). Sepharose CL-6B, DEAE-Sephacel, and blue dextran were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.). High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade 6 N HCl was from Pierce. Polystyrene petri dishes (Falcon 1058) were from Becton Dickinson Labware (Franklin Lakes, N.J.).

Placenta samples.

Tissues were obtained from placentas at 16, 24, 28, 33, and 38 weeks of gestation from pregnant women who had abortion because of P. falciparum infection or had normal delivery at the Central Hospital, Yaounde, Cameroon. For studies with placentas at 16, 24, 28, and 33 weeks, tissue from one placenta at each gestational age was used. In the case of the term placentas (38 or 39 weeks), CSPGs from several placentas were studied, and the results from one representative placenta are reported here. The nature of the project was explained to the women, and verbal informed consent was obtained. Ethical clearance for the research was obtained from the Ethical Committee, Ministry of Health, Yaounde, and the Institutional Review Board at Georgetown University. (The project is covered by single-project assurance number S-9601-01.) The placentas were stored for 2 to 3 weeks at −70°C, transported to the United States on dry ice, and stored again at −70°C until used.

Isolation of placental intervillous space CSPGs.

All procedures were performed at 4°C in a cold room. The placental tissues were cut into small pieces, minced, and suspended in 100 to 150 ml of PBS-10 mM EDTA (pH 7.2) containing 2% Tween 20, 6 M urea, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mM TLCK, 0.25 mM TPCK, 1 mM benzamidine, and 0.1 mM N-ethylmaleimide. The suspensions were stirred for 2 to 3 h and centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 rpm in a Sorvall RC2-B centrifuge with an SS-34 rotor. The pellets were extracted as described above three more times. The supernatants were applied to DEAE-Sephacel columns (3.5 by 12 cm). The columns were washed with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), containing 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 4 M urea until the absorption at 280 nm was <0.02 absorption unit and then equilibrated with 50 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc)-150 mM NaCl (pH 5.5) containing 4 M urea. The bound glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans were eluted with a 0.15 to 0.80 M NaCl linear gradient in 50 mM NaOAc (pH 5.5) containing 4 M urea. Ten-milliliter fractions were collected, absorption at 260 and 280 nm was measured, and aliquots were analyzed for uronic acid content by the carbazole method (530 nm) (9). The uronic acid-positive fractions were pooled, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

Purification of CSPGs by CsBr density gradient centrifugation.

The crude lyophilized CSPGs (fraction I from various placentas [Fig. 1 ]) were dissolved (1 to 2 mg/ml) in 25 mM sodium phosphate-50 mM NaCl (pH 7.2) containing 0.02% NaN3, 4 M guanidine-HCl, and 42% (wt/wt) CsBr. The solutions were centrifuged in a Beckman 50 Ti rotor at 44,000 rpm for 65 h at 14°C (44). Gradients were aspirated from the bottom of the tubes with a peristaltic pump by carefully inserting glass capillaries. Fractions (0.67 ml) were collected, screened for protein (280 nm), and aliquots assayed for uronic acid (530 nm). The densities (grams per milliliter) of fractions were determined by weighing. The uronic acid-positive fractions were pooled, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

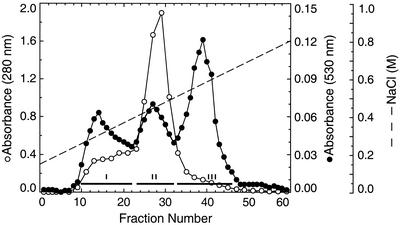

FIG. 1.

Isolation of CSPGs from extracts of human placentas by DEAE-Sephacel chromatography. The extracts of human placentas were passed through columns of DEAE-Sephacel (3.5 by 12 cm) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0.15 to 0.8 M NaCl. Shown is the elution pattern of proteoglycans from the extract of a 16-week-old placenta. The extracts of 24-, 28-, 33-, and 38-week-old placentas showed similar elution patterns (not shown). Note that the uronic acid levels in fractions 23 to 32 are significantly lower than indicated by absorption at 530 nm because of interference by the high contents of coeluted proteins and nucleic acids. Fractions containing CSPGs were pooled as indicated by the horizontal bars. Fraction I, containing the CSPGs of the placental intervillous spaces, was studied further.

Treatment of CSPGs with S. hyalurolyticus hyaluronidase.

The CSPGs (4 to 5 mg), purified by CsBr gradient centrifugation, were dissolved in 0.5 ml of 20 mM NaOAc-150 mM NaCl (pH 6.0) and incubated with S. hyalurolyticus hyaluronidase (50 turbidity-reducing units) at 60°C for 2 h in the presence of protease inhibitors (20). The digests were dialyzed against water and lyophilized.

Treatment of CSPGs with heparitinase.

The hyaluronidase-treated material (see above) was incubated with heparitinase (25 mU/mg of proteoglycan) in 0.5 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl-1 μM calcium acetate (pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors at 43°C for 3 h (21). The solutions were dialyzed against water and lyophilized.

Purification of CSPGs by gel filtration.

The hyaluronidase- and heparitinase-treated CSPGs from various placentas were chromatographed on Sepharose CL-6B columns (2 by 65 cm) in 20 mM Tris-HCl-150 mM NaCl (pH 7.6) containing 4 M guanidine-HCl. Fractions (3.6 ml) were collected, absorption at 280 nm was measured, and aliquots were assayed for uronic acid content (9). The proteoglycan-containing fractions were combined, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

Hexosamine compositional analysis

The purified CSPGs (5 to 10 μg) were hydrolyzed with 4 M HCl at 100°C for 6 h. The hydrolysates were dried in a Speed-Vac and analyzed on a CarboPac PA1 high-pH anion-exchange HPLC column (4 by 250 mm; Dionex) (19). The elution was with 20 mM sodium hydroxide, and elution of sugars was monitored by pulsed amperometric detection. The response factor for each sugar was determined by using standard sugar solutions.

Enzymatic digestion of CSPGs and disaccharide compositional analysis.

The purified CSPGs (20 to 30 μg) were digested with the following enzymes as described previously (2): (i) chondroitinase ABC (10 to 20 mU) in 50 μl of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 30 mM NaOAc and 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37°C for 5 to 10 h, (ii) chondroitinase AC II (50 mU) in 50 μl of 100 mM NaOAc (pH 6.0) containing 0.01% BSA at 37°C for 30 min, and (iii) chondroitinase B (10 mU) in 50 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.05% BSA at 30°C for 2 h. The proteins in the enzyme digests were precipitated by the addition of 4 volumes of cold methanol and centrifuged, and the supernatant was dried in a Speed-Vac. The residues were dissolved in water and analyzed on a 4.6- by 250-mm amine-bonded silica PA03 column with Waters (Milford, Mass.) 600E HPLC with a linear gradient of 16 to 530 mM NaH2PO4 over 70 min at room temperature at a flow rate of 1 ml/min (2, 41). The elution of unsaturated disaccharides was monitored by measuring the absorption at 232 nm with a Waters 484 variable-wavelength UV detector.

P. falciparum cell culture.

The 3D7 strain of P. falciparum, selected for CSPG binding as described previously (3), was used for all of the IRBC binding studies. The parasites were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 29 mM sodium bicarbonate, 0.005% hypoxanthine, p-aminobenzoic acid (2 mg/liter), gentamicin sulfate (50 mg/liter), and 10% O-positive human serum with type O-positive human RBCs at a 3% hematocrit. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 90% N2, 5% O2, and 5% CO2 (3).

IRBC binding and inhibition assays.

The solutions (10 to 15 μl) of the purified CSPGs (various concentrations in PBS [pH 7.2]) were applied as 4-mm-diameter circular spots on 150- by 15-mm plastic petri dishes at 4°C overnight. The nonspecific binding sites in the spots were blocked with 2% BSA at room temperature for 2 h and then overlaid with a 2% suspension of IRBCs (25 to 30% parasitemia) in RPMI 1640 medium or PBS (pH 7.2) (3). Uninfected RBCs overlaid on CSPG-coated plates were used as negative controls. After a 40-min incubation, the petri dishes were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.2). The bound IRBCs were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde, stained with 1% Giemsa stain, and counted under light microscopy. All assays were performed in duplicate.

The CSPGs purified from placentas of different gestational ages were tested for their ability to inhibit IRBC binding to CSPGs from the term placenta. Petri dishes were coated with CSPG (200 ng/ml in PBS [pH 7.2]), and the nonspecific binding sites in the spots were blocked as described above. A 2% suspension of IRBCs (25 to 30% parasitemia) was incubated with CSPGs from various placentas at the indicated concentrations in PBS (pH 7.2) in 96-well microtiter plates at room temperature for 30 min with intermittent mixing (3). The IRBC suspension was then layered onto the CSPG-coated spots on petri dishes. After 40 min at room temperature, the unbound cells were removed by washing and the bound IRBCs were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde, stained with Giemsa stain, and counted under light microscopy. The numbers of IRBCs in 3 or 4 fields were averaged, and IRBCs per square millimeter were calculated.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of CSPGs of the intervillous spaces of human placentas of different gestational ages.

In a previous study, we used differential extraction procedures to isolate proteoglycans present at different locations in the human placenta, including intervillous spaces, cell surfaces, and tissue matrix (2). These proteoglycan types eluted at different salt concentrations when chromatographed on DEAE-Sephacel columns due to differences in their overall charge densities. Therefore, in this study, placentas were directly extracted with buffer containing detergent and urea, and the three classes of proteoglycans were fractionated by DEAE-Sephacel chromatography with an NaCl gradient. Thus, from placentas of each gestational age, three proteoglycan peaks, FI, FII, and FIII, were obtained (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Preliminary analysis revealed that the CSPG fraction that eluted with 0.35 M NaCl (fraction FI) was similar to the previously identified low-sulfated CSPGs of the intervillous spaces of the placenta (2). Fractions FII and FIII, which eluted with 0.5 and 0.7 M NaCl, represented the cell-associated CSPGs and tissue matrix dermatan sulfate proteoglycans, respectively (2). Since low-sulfated CSPGs of the placental intervillous spaces are the major receptor for IRBC sequestration in the placenta (2), fraction FI from placentas of various gestational periods were further purified and characterized.

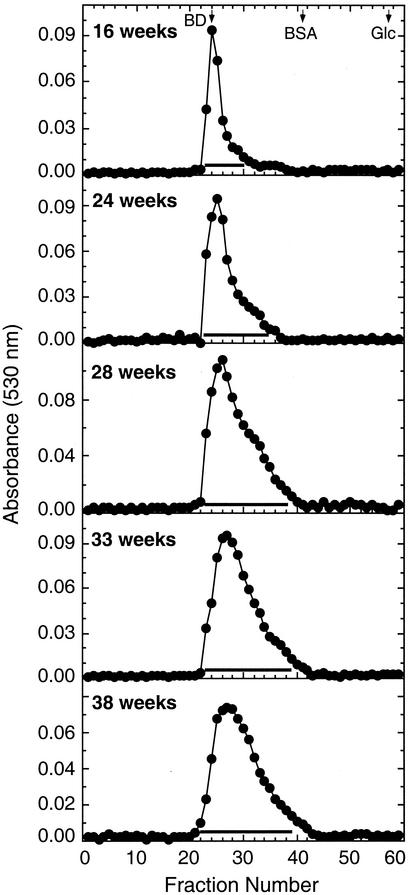

On purification by CsBr density gradient centrifugation, the CSPGs (average density, 1.43 g/ml) were separated from the associated proteins (average density, <1.35 g/ml) that remained at the top of the gradients and nucleic acid impurities (average density, >1.50 g/ml) that settled to the bottom of the gradients (not shown). The CsBr density gradient fractionation patterns of FI from various placentas resembled that previously reported for the CSPGs of the placental intervillous spaces (2). The purified proteoglycan fractions FI from placentas of various gestational periods had ∼80% galactosamine and ∼20% glucosamine, suggesting the presence of hyaluronic acid and/or heparan sulfate in the CSPG fractions. Therefore, in the second step of the purification, to remove these associated glycosaminoglycans, the FI material was treated successively with S. hyalurolyticus hyaluronidase and heparitinase, and the CSPGs were recovered. When chromatographed on Sepharose CL-6B, the CSPGs from 16-week-old placentas eluted as an excluded symmetrical peak, whereas the CSPGs from >24-week-old placentas, in each case, eluted as broad asymmetrical peak with unresolved shoulders at the tailing edges (Fig. 2). Significant portions of the CSPGs from >24-week placentas eluted in the included volumes. The amount of CSPGs in the included volume increased with the gestational age, indicating that the molecular size of the CSPGs of the placental intervillous spaces gradually decreases with increasing gestational age. The 16-week-old placentas contained primarily high-molecular-weight CSPGs, whereas older placentas contained high levels of low-molecular-weight CSPGs (Fig. 2). The average molecular mass decreased from 1,030 kDa for CSPGs from 16-week-old placenta to 690 kDa for CSPGs of 38-week-old placentas (Table 1). The elution profiles also revealed that the decrease in molecular size from younger to older placentas was accompanied by a parallel increase in polydispersity with increased proportions of low-molecular-weight CSPGs (Fig. 2). The CSPGs from various placentas were pooled as shown in Fig. 2. The increase in polydispersity of CSPGs could be due to either the proteolytic processing of the core proteins or the expression of additional distinct low-molecular-weight CSPGs in placentas of >24 weeks.

FIG. 2.

Sepharose CL-6B chromatography of placental intervillous space CSPGs. The CSPGs from placentas of various gestational ages, after purification by CsBr density gradient centrifugation as described previously (2), were chromatographed on Sepharose CL-6B columns (2 by 65 cm) in 50 mM sodium acetate-150 mM NaCl (pH 6.0) containing 4 M guanidine-HCl. The column was calibrated with standard molecular weight marker proteins. The elution position of blue dextran (BD), BSA, and glucose (Glc) are indicated. The CSPG-containing fractions were pooled as indicated by the horizontal bars, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

TABLE 1.

Yield, molecular mass, and composition of CSPGs purified from human placentas of different gestational ages

| Gestational age (wk) | Yield (mg)a/100 g of tissue | Molecular mass (kDa)b | HexN composition (%)c

|

Disaccharide composition (%)d

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GalN | GlcN | Δdi-0S | Δdi-4S | Δdi-6S | |||

| 16 | 2.5 | 1,030 | 96 | 4 | 97 | 4 | 0 |

| 24 | 2.7 | 920 | 95 | 5 | 93 | 7 | 0 |

| 28 | 2.9 | 800 | 94 | 6 | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| 33 | 2.8 | 690 | 95 | 5 | 91 | 9 | 0 |

| 38 | 2.8 | 690 | 94 | 6 | 91 | 9 | 0 |

Yields normalized to 100 g of placental tissue weight.

Determined by chromatography on a calibrated Sepharose CL-6B column.

Determined by HPLC analysis of 4 M HCl hydrolysates of CSPGs. HexN, hexosamine; GalN, galactosamine; GlcN, glucosamine.

Determined by HPLC analysis of unsaturated disaccharides released by digestion of CSPGs with chondroitinase ABC.

The yields and compositions of the purified CSPGs are given in Table 1. The overall amounts of low-sulfated CSPGs per 100 g of placenta tissue were similar in placentas of different gestational ages (Table 1). Hexosamine compositional analysis showed that the purified CSPG preparations contained 94 to 96% galactosamine and 4 to 6% glucosamine (Table 1); as reported previously, the presence of the latter sugar was due to glycoprotein-type oligosaccharides (2). Consistent with these results, chondroitinase ABC completely degraded the glycosaminoglycan chains of all of the CSPG preparations, suggesting the absence of detectable levels of hyaluronic acid or heparan sulfate in the purified proteoglycan fractions. The glycosaminoglycan chains of the CSPGs were also completely susceptible to chondroitinase AC II, but they were resistant to chondroitinase B (not shown). These results suggest that the purified proteoglycans were entirely C4S and lacked dermatan sulfate structural features.

HPLC analysis of the unsaturated disaccharides formed by digestion with chondroitinase ABC indicated that the glycosaminoglycan chains of the CSPGs, from placentas of various gestational age, consisted predominantly of nonsulfated disaccharide repeating units, with small but significant amounts of 4-sulfated disaccharides. There was no detectable 6-sulfation in any of the proteoglycan fractions (Table 1). These results agree with the previously reported disaccharide compositions for the low-sulfated CSPGs of the intervillous spaces purified from full-term placentas (2). The sulfate content of the CSPGs moderately increased after 24 weeks of gestation (Table 1).

Binding of IRBCs to the purified placental CSPGs.

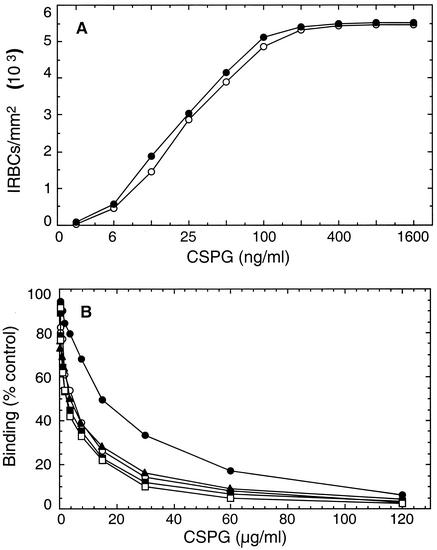

The purified CSPGs of the placental intervillous spaces were assessed for their ability to support IRBC binding in a cytoadherence assay (2, 3). The CSPGs from various placentas showed no noticeable difference in their ability to bind IRBCs (Fig. 3A). This is surprising in view of the considerable increase in sulfate content of the CSPGs from placentas of >24 weeks of gestation. Based on the sulfate content of CSPGs and the level of sulfate content required for optimal IRBC binding, i.e., ∼30% 4-sulfate groups in the dodecasaccharide minimum CS chain length (3), it is predicted that the CSPGs from >24-week-old placentas should bind IRBCs with higher affinity than the CSPGs from 16-week-old placentas. However, when the binding capacities of the CSPGs were measured by an adhesion inhibition assay by coating the CSPG from a normal 39-week-old placenta, the CSPGs from >24-week-old placentas showed a somewhat higher level of inhibition than the CSPGs from 16-week-old placentas (Fig. 3B). This difference appears to be not significant with regard to the density of IRBC binding in the placenta, because, as shown in the Fig. 3A, the CSPGs from 16-week-old placentas were as efficient as the CSPGs from >24-week old placentas. Furthermore, the binding capacities of the CSPGs purified from P. falciparum-infected placentas (those from the Cameroonian individuals) were similar to those of the CSPGs purified from uninfected placentas from individuals who had never been infected with P. falciparum (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Adherence of IRBCs to the placental CSPGs. (A) CSPGs purified from placentas of various gestational ages were applied to plastic petri dishes at the indicated concentrations, blocked with BSA, and then overlaid with IRBCs. The unbound cells were washed, and bound cells were fixed, stained, and counted under a light microscope. Shown is the dose-dependent binding of IRBCs to CSPGs from 16 (○)- and 33 (•)-week-old placentas. The IRBC binding patterns of CSPGs from 24-, 28-, and 38-week-old placentas were similar to those of CSPGs from 16- and 33-week-old placentas (not shown). (B) CSPGs previously purified from a full-term placenta, i.e., BCSPG-2 fraction (2), were applied at 200 ng/ml and blocked with BSA. IRBCs, incubated with the CSPGs at the indicated concentrations (expressed with respect to their CS chain contents) of various placentas, were layered on CSPG-coated spots. The unbound cells were washed, and bound cells were fixed, stained with Giemsa stain, and counted under a light microscope. •, CSPGs from 16-week-old placentas; ○, CSPGs from 24-week-old placentas; ▴, CSPGs from 28-week-old placentas; ▪, CSPGs from 33-week-old placentas; □, CSPGs from 38-week-old placentas.

DISCUSSION

In pregnant women infected with P. falciparum, the peak prevalence of infection occurs at 13 to 20 weeks of gestation (7, 45). Since CSPGs are the receptors for the adherence of IRBCs in the intervillous spaces of the human placenta, the CSPGs must be expressed in significant levels toward the end of the first trimester or the beginning of the second trimester of pregnancy. The biochemical evidence presented here demonstrates that CSPGs are indeed expressed early in pregnancy. Our data clearly demonstrate that significant levels of CSPGs are expressed in the intervillous spaces of the placenta by 16 weeks and throughout the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Thus, CSPGs are available to mediate sequestration of IRBCs. The presence of CSPGs in the placentas before 16 weeks could not be studied because of the nonavailability of the tissue. However, based on the observed pattern of CSPG expression during the second and third trimesters, it is likely that significant levels of CSPGs are expressed during the later part of the first trimester. The results of this study also demonstrate that CSPGs of the intervillous spaces undergo significant changes with regard to the molecular weight, polydispersity, and degree of 4-sulfation during the course of pregnancy (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The observed increase in the levels of sulfation in CSPGs with increasing gestational age agrees with the results of a previous study (23). From determination of the sulfate contents of the total CS and CS-dermatan sulfate copolymeric chains from pooled placentas of 16 to 24 weeks and full term, it was reported that the sulfate content of the glycosaminoglycans increases with increasing gestational age (23). However, in that study, different classes of CSPGs in the placentas, their structural characteristics, and levels of expression during the course of pregnancy were not studied. The results of this study, however, clearly demonstrate the expression of CSPGs during the second and third trimesters and show that the CSPGs from placentas of various gestational ages can efficiently bind IRBCs. Thus, our data establish the relevance of CSPG receptors in binding of IRBCs in the placenta at various gestational ages.

In areas where malaria is endemic, pregnant women exhibit a peak prevalence of P. falciparum infection during weeks 13 to 20 (7, 45). Pregnant women produce C4S-IRBC adhesion-inhibitory antibodies in a gestational age-dependent manner (32, 38), and they either lack or have very low levels of antibodies at conception and produce antibodies in the second trimester. The kinetics of antibody production when considered with the pattern of parasite prevalence in pregnant women suggests that the antibodies are produced in response to the P. falciparum infection in the placenta. Since placentas express significant level of CSPGs during the early part of the second trimester, the previously reported pattern of prevalence of parasite infection appears to be closely related to the expression of extracellular CSPGs in the intervillous spaces.

Our data are consistent with the following sequence of events. Only plasma perfuses the intervillous space during the first trimester, since maternal blood flow is not fully established prior to week 12 of gestation (10). Therefore, IRBCs adhere in the intervillous spaces only after week 12, even if CSPGs are expressed prior to 12 weeks of gestation. Thus, based on our data, it is likely that the high prevalence of P. falciparum infection during weeks 13 to 20 of pregnancy occurs during the rapid expansion of the placenta and corresponds with the concomitant expression of significant levels of extracellular CSPGs in the intervillous spaces and establishment of maternal blood flow into the area. Since pregnant women have little or no C4S-IRBC adhesion-inhibitory antibodies prior to 12 to 20 weeks of gestation (32), IRBCs can efficiently bind to CSPGs in the placenta, resulting in a high prevalence of P. falciparum infection during this period. Because of selection of C4S-adherent P. falciparum by placental CSPGs, the parasites efficiently increase in number, causing placental malaria. However, the subsequent production of C4S-IRBC adhesion-inhibitory antibodies and possibly other protective immune responses results in the clearance of IRBCs from the placenta. This leads to the observed recovery from infection during the second and third trimesters. Since the level of expression of CSPGs in the placenta stays fairly constant after 24 weeks of gestation (Table 1), it is clear that recovery from placental malaria is not due to a decrease in the level of CSPG expression.

The CSPGs of younger placentas, when immobilized on a solid surface, can bind IRBCs as efficiently as the CSPGs of term placentas. This is despite the presence of relatively lower sulfate contents in the CSPGs of younger placentas compared to older placentas. However, in the inhibition assay, the CSPGs of 16-week-old placentas were significantly less inhibitory than CSPGs of >24-week old placentas, suggesting that the CSPGs of older placentas should adhere to IRBCs more efficiently than CSPGs of younger placentas. This apparent discrepancy can be explained based on recent observations in our laboratory. We recently found that the sulfate groups in the CS chains of placental CSPGs are clustered at a density of 20 to 28% in CS chain domains, which range in size from 6 to 14 disaccharide residues (1). The oligosaccharides corresponding to these sulfate-rich regions, obtained by the action of an endoenzyme that specifically degrades nonsulfated regions, efficiently inhibited the IRBC adhesion. Therefore, the CS chains with relatively high levels of sulfate groups are likely to have higher numbers of sulfate-clustered regions, which can effectively support IRBC binding. However, because of the steric constraints, the bulky IRBCs may not be able to adhere to all of the closely spaced sites, and thus not all of the available binding sites of the CS chains of the CSPGs immobilized on solid surfaces can bind IRBCs. In solution phase, on the other hand, the disposition of the IRBCs in three-dimensional space might allow for effective interactions even with the closely spaced binding sites in the CS chains. Therefore, CS chains with higher levels of IRBC binding sites can more efficiently inhibit the IRBC adhesion than CS chains with fewer binding sites. However, IRBCs can efficiently bind to CSPGs from placentas of all gestational ages when immobilized on solid surfaces (Fig. 3). Thus, it is likely that IRBCs can adhere in the intervillous spaces of ≤16-week-old placentas as efficiently as in those of >24-week-old placentas.

In summary, the results of this study establish, for the first time, that CSPGs are expressed in the intervillous spaces of the placenta during the entire period of the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The high prevalence of P. falciparum infection in pregnant women likely occurs immediately after the gestational age at which CSPGs appear at high levels in the placenta, a time when women lack C4S-IRBC adhesion-inhibitory antibodies. The subsequent recovery from infection due to the production of adhesion-inhibitory antibodies, and possibly other immune responses, mediates clearance of IRBCs from the placenta. If the first exposure of the placenta to parasite infection is delayed, occurring only in the later stages of gestation, the women are likely to experience high levels of placental parasites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-45086 (to D.C.G.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. S.T.A.-E. was supported by Fogarty International Center training grant 5D43TWO1264 (to D.W.T.) from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank V. P. Bhavanandan, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, for critical reading of the manuscript.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achur, R. N., M. Valiyaveettil, and D. C. Gowda. The low sulfated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of human placenta have sulfate group-clustered domains that can efficiently bind Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Achur, R. N., M. Valiyaveettill, A. Alkhalil, C. F. Ockenhouse, and D. C. Gowda. 2000. Characterization of proteoglycans of human placenta and identification of unique chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan of the intervillous spaces that mediates the adherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to the placenta. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40344-40356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhalil, A., R. N. Achur, M. Valiyaveettil, C. F. Ockenhouse, and D. C. Gowda. 2000. Structural requirements for the adherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of human placenta. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40357-40364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baird, J. K. 1995. Host age as a determinant of naturally acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Parasitol. Today 11:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baruch, D. I., J. A. Gormely, C. Ma, R. J. Howard, and B. L. Pasloske. 1996. P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein is a parasitized erythrocyte receptor for adherence to CD36, thrombospondin, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3497-3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeson, J. G., J. C. Reeder, S. J. Rogerson, and G. V. Brown. 2001. Parasite adhesion and immune evasion in placental malaria. Trends Parasitol. 17:331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brabin, B. J. 1983. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull. W. H. O. 61:1005-1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buffet, P. A., B. Gamain, C. Scheidig, D. I. Baruch, J. D. Smith, R. Hernandez-Rivas, B. Pouvelle, S. Oishi, N. Fujii, T. Fusai, D. Parzy, L. H. Miller, J. Gysin, and A. Scherf. 1999. Plasmodium falciparum domain mediating adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A: a receptor for human placental infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12743-12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dische, Z. 1947. A new specific color reaction of hexuronic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 167:189-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox, H. 1997. Major problems in pathology. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 11.Fried, M., and P. E. Duffy. 1996. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science 272:1502-1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried, M., R. O. Muga, A. O. Misore, and P. E. Duffy. 1998. Malaria elicits type 1 cytokines in the human placenta: IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha associated with pregnancy outcomes. J. Immunol. 160:2523-2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried, M., F. Nosten, A. Brockman, B. J. Brabin, and P. E. Duffy. 1998. Maternal antibodies block malaria. Nature 395:851-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamain, B., S. Gratepanche, L. H. Miller, and D. I. Baruch. 2002. Molecular basis for the dichotomy in Plasmodium falciparum adhesion to CD36 and chondroitin sulfate A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10020-10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner, J. P., R. A. Pinches, D. J. Roberts, and C. I. Newbold. 1996. Variant antigens and endothelial receptor adhesion in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3503-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood, B., and T. Mutabingwa. 2002. Malaria in 2002. Nature 415:670-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gysin, J., B. Pouvelle, M. L. Tonqueze, L. Edelman, and M.-C. Boffa. 1997. Chondroitin sulfate of thrombomodulin is an adhesion receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 88:267-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gysin, J., B. Pouvelle, N. Fievet, A. Scherf, and C. Lepolard. 1999. Ex vivo desequestration of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes from human placenta by CSA. Infect. Immun. 67:6596-6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy, M. R. 1989. Monosaccharide analysis of glycoconjugates by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 179:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatae, Y., and A. Makita. 1975. Colorimetric determination of hyaluronate degraded by Streptomyces hyaluronidase. Anal. Biochem. 64:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hovingh, P., and A. Linker. 1974. The disaccharide repeating-units of heparan sulfate. Carbohydr. Res. 37:181-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ismail, M. R., J. Ordi, C. Menendez, P. J. Ventura, J. J. Aponte, E. Kahigwa, R. Hirt, A. Cardesa, and P. L. Alonso. 2000. Placental pathology in malaria: a histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum. Pathol. 31:85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, T. Y., A. M. Jamieson, and I. A. Schafer. 1973. Changes in the composition and structure of glycosaminoglycans in the human placenta during development. Pediatr. Res. 7:965-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maubert, B., L. J. Guilbert, and P. Deloron. 1997. Cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and chondroitin 4-sulfate expressed by the syncytiotrophoblast in the human placenta. Infect. Immun. 65:1251-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maubert, B., N. Fievet, G. Tami, C. Boudin, and P. Deloron. 2000. Cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in the placenta. Parasite Immunol. 22:191-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGregor, I. A., M. E. Wilson, and W. Z. Billewicz. 1983. Malaria infection of the placenta in the Gambia, West Africa; its incidence and relationship to still birth, birth weight and placental weight. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:232-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menendez, C. 1995. Malaria during pregnancy: a priority area of malaria research and control. Parasitol. Today 11:178-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menendez, C., J. Ordi, M. R. Ismail, P. J. Ventura, J. J. Aponte, E. Kahigwa, F. Font, and P. L. Alonso. 2000. The impact of placental malaria on gestational age and birth weight. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1740-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, L. H., D. I. Baruch, K. Marsh, and O. K. Doumbo. 2002. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Science 415:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, L. H., and J. D. Smith. 1998. Motherhood and malaria. Nat. Med. 4:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noviyanti, R., G. V. Brown, M. E. Wickham, M. F. Duffy, A. F. Cowman, and J. C. Reeder. 2001. Multiple var gene transcripts are expressed in Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes selected for adhesion. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 114:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Neil-Dunne, I., R. N. Achur, S. T. Agbor-Enoh, M. Valiyaveettil, R. S. Naik, C. F. Ockenhouse, A. Zhou, R. Megnekou, R. Leke, D. W. Taylor, and D. C. Gowda. 2001. Gravidity-dependent production of antibodies that inhibit the binding of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to placental chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan during pregnancy. Infect. Immun. 69:7487-7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeder, J. C., A. F. Cowman, K. M. Davern, J. G. Beeson, J. K. Thompson, S. J. Rogerson, and G. V. Brown. 1999. The adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate A is mediated by P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5198-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricke, C. H., T. Staalsoe, K. Koram, B. D. Akanmori, E. M. Riley, T. G. Theander, and L. Hviid. 2000. Plasma antibodies from malaria-exposed pregnant women recognize variant surface antigens on P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes in a parity-dependent manner and block parasite adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A. J. Immunol. 165:3309-3316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riley, E. M., L. Hviid, and T. G. Theander. 1994. Malaria, p. 119-143. In F. Kierszenbaum (ed.), Parasite infections and the immune system. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 36.Rogerson, S. J., and G. V. Brown. 1997. Chondroitin sulphate A as an adherence receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Parasitol. Today 13:70-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snow, R. W., M. Craig, U. Diechmann, and K. Marsh. 1999. Estimating mortality, morbidity and disability due to malaria among Africa's non-pregnant population. Bull. W. H. O. 77:624-640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staalsoe, T., R. Megnekou, N. Fievet, C. H. Ricke, H. D. Zornig, R. Leke, D. W. Taylor, P. Deloron, and L. Hviid. 2001. Acquisition and decay of antibodies to pregnancy-associated variant antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes that protect against placental parasitemia. J. Infect. Dis. 184:618-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steketee, R. W., B. L. Nahlen, M. E. Parise, and C. Menendez. 2001. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 64:28-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su, X. Z., V. M. Heatwole, S. P. Wertheimer, F. Guinet, J. A. Herrfeldt, D. S. Peterson, J. A. Ravetch, and T. E. Wellems. 1995. The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell 82:89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugahara, K., K. Shigeno, M. Masuda, N. Fujii, A. Kurosaka, and K. Takeda. 1994. Structural studies on the chondroitinase ABC-resistant sulfated tetrasaccharides isolated from various chondroitin sulfate isomers. Carbohydr. Res. 255:145-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter, P. R., Y. Garin, and P. Blot. 1982. Placental pathologic changes in malaria. A histologic and ultrastructural study. Am. J. Pathol. 109:330-342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada, M., R. Steketee, C. Abramowsky, M. Kida, J. Wirima, D. Heymann, J. Rabbege, J. Breman, and M. Aikawa. 1989. Plasmodium falciparum associated placental pathology: a light and electron microscopic and immunohistologic study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 41:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yphantis, D. A. 1964. Equilibrium ultracentrifugation in dilute solution. Biochemistry 3:297-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou, A., R. Megnekou, R. Leke, J. Fogako, S. Metenou, B. Trock, D. W. Taylor, and R. F. Leke. 2002. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum infection in pregnant Cameroonian women. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67:566-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]