Abstract

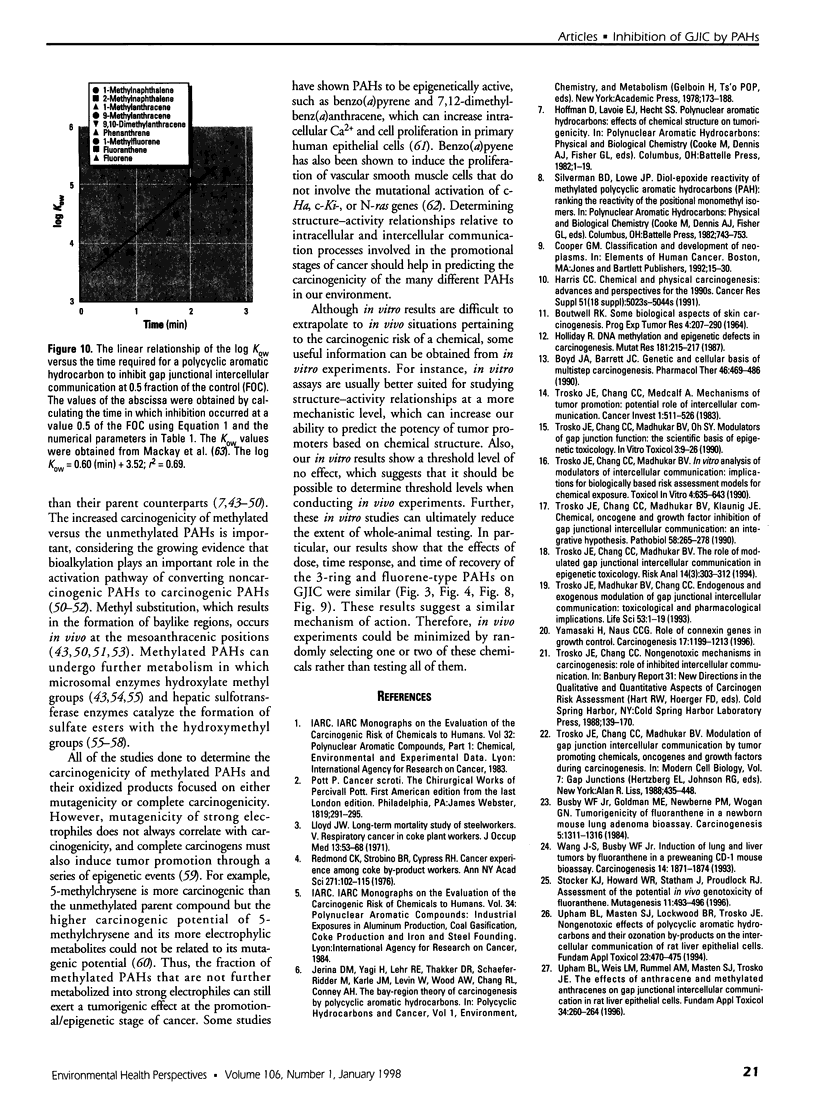

Many polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are known carcinogens, and a considerable amount of research has been devoted to predicting the tumor-initiating potential of PAHs based on chemical structure. However, there has been little research into the effects of PAHs on the epigenetic events of tumor promotion and no structural correlation has been made thereof. Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) activity was used in this study as an epigenetic biomarker to determine the structure-activity relationships of twelve different PAHs. The PAHs used were naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, 2-methylnaphthalene, anthracene, 1-methylanthracene, 2-methylanthracene, 9-methylanthracene, 9, 10-dimethylanthracene, phenanthrene, fluorene, 1-methylfluorene, and fluoranthene. Results showed that PAHs containing bay or baylike regions inhibited GJIC more than did the linear PAHs. The nonnaphthalene PAHs were not cytotoxic as determined by a vital dye uptake assay, but the naphthalene compounds were cytotoxic at the higher doses, indicating that the down regulation of GJIC by these naphthalenes could be a consequence of general membrane damage. Inhibition of GJIC by all the inhibitory PAHs was reversed when the cells were refreshed with PAH-free growth medium. Inhibition of GJIC occurred within 0.5-5 min and correlated with the aqueous solubility of the PAHs. The present study revealed that there are structural determinants of epigenetic toxicity as determined by GJIC activity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BOUTWELL R. K. SOME BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SKIN CARCINOGENISIS. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1964;4:207–250. doi: 10.1159/000385978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenfreund E., Puerner J. A. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett. 1985 Feb-Mar;24(2-3):119–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. A., Barrett J. C. Genetic and cellular basis of multistep carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;46(3):469–486. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby W. F., Jr, Goldman M. E., Newberne P. M., Wogan G. N. Tumorigenicity of fluoranthene in a newborn mouse lung adenoma bioassay. Carcinogenesis. 1984 Oct;5(10):1311–1316. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.10.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y. L., Gray T. J., Ioannides C. Mutagenicity of chrysene, its methyl and benzo derivatives, and their interactions with cytochromes P-450 and the Ah-receptor; relevance to their carcinogenic potency. Toxicology. 1993 Jul 11;81(1):69–86. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90157-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALK H. L., KOTIN P., THOMPSON S. INHIBITION OF CARCINOGENESIS. THE EFFECT OF HYDROCARBONS AND RELATED COMPOUNDS. Arch Environ Health. 1964 Aug;9:169–179. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1964.10663816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesher J. W., Myers S. R. Bioalkylation of benz[a]anthracene as a biochemical probe for carcinogenic activity. Lack of bioalkylation in a series of six noncarcinogenic polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Drug Metab Dispos. 1990 Mar-Apr;18(2):163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesher J. W., Myers S. R. Rules of molecular geometry for predicting carcinogenic activity of unsubstituted polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1991;11(1):41–54. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesher J. W., Myers S. R., Stansbury K. H. The site of substitution of the methyl group in the bioalkylation of benzo[a]pyrene. Carcinogenesis. 1990 Mar;11(3):493–496. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C. C. Chemical and physical carcinogenesis: advances and perspectives for the 1990s. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep 15;51(18 Suppl):5023s–5044s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D., Rathkamp G., Nesnow S., Wynder E. L. Fluoranthenes: quantitative determination in cigarette smoke, formation by pyrolysis, and tumor-initiating activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972 Oct;49(4):1165–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R. DNA methylation and epigenetic defects in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1987 Dec;181(2):215–217. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(87)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Engman L., Cotgreave I. A. Redox-active chalcogen-containing glutathione peroxidase mimetics and antioxidants inhibit tumour promoter-induced downregulation of gap junctional intercellular communication between WB-F344 liver epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1995 Aug;16(8):1815–1824. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.8.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Speisky H., Cotgreave I. A. The inhibitory effects of boldine, glaucine, and probucol on TPA-induced down regulation of gap junction function. Relationships to intracellular peroxides, protein kinase C translocation, and connexin 43 phosphorylation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995 Nov 9;50(10):1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara T., Motohashi N., Pang G. L., Higano M., Kiguchi K., Molnár J. Correlations between topological resonance energy of methyl-substituted benz[c]acridines, benzo[a]phenothiazines and chrysenes, and their carcinogenic or antitumor activities. Anticancer Res. 1996 Sep-Oct;16(5A):2757–2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Voie E. J., Coleman D. T., Rice J. E., Geddie N. G., Hoffmann D. Tumor-initiating activity, mutagenicity, and metabolism of methylated anthracenes. Carcinogenesis. 1985 Oct;6(10):1483–1488. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.10.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie E. J., Tulley-Freiler L., Bedenko V., Hoffman D. Mutagenicity, tumor-initiating activity, and metabolism of methylphenanthrenes. Cancer Res. 1981 Sep;41(9 Pt 1):3441–3447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J. W. Long-term mortality study of steelworkers. V. Respiratory cancer in coke plant workers. J Occup Med. 1971 Feb;13(2):53–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers S. R., Blake J. W., Flesher J. W. Bioalkylation and biooxidation of anthracene, in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988 Mar 30;151(3):1441–1445. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers S. R., Flesher J. W. Bioalkylation of benz[a]anthracene, 7-methylbenz[a]anthracene, and 12-methylbenz[a]anthracene in rat lung cytosol preparations. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991 Jun 1;41(11):1683–1689. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90170-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norpoth K., Kemena A., Jacob J., Schümann C. The influence of 18 environmentally relevant polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and Clophen A50, as liver monooxygenase inducers, on the mutagenic activity of benz[a]anthracene in the Ames test. Carcinogenesis. 1984 Jun;5(6):747–752. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.6.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROE F. J. Effect of phenanthrene on tumour-initiation by 3,4-benzopyrene. Br J Cancer. 1962 Sep;16:503–506. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1962.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C. K., Strobino B. R., Cypess R. H. Cancer experience among coke by-product workers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;271:102–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb23099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINER P. E., FALK H. L. Summation and inhibition effects of weak and strong carcinogenic hydrocarbons: 1:2-benzanthracene, chrysene, 1:2:5:6-dibenzanthracene, and 20-methylcholanthrene. Cancer Res. 1951 Jan;11(1):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaga T. J., Bowden G. T., Scribner J. D., Boutwell R. K. Dose-response studies on the ability of 7,12-dimethylbenz(alpha)anthracene and benz(alpha)anthracene to initiate skin tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974 Nov;53(5):1337–1340. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.5.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker K. J., Howard W. R., Statham J., Proudlock R. J. Assessment of the potential in vivo genotoxicity of fluoranthene. Mutagenesis. 1996 Sep;11(5):493–496. doi: 10.1093/mutage/11.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y. J., Liem A., Miller E. C., Miller J. A. 7-Sulfooxymethyl-12-methylbenz[a]anthracene is an electrophilic mutagen, but does not appear to play a role in carcinogenesis by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene or 7-hydroxymethyl-12-methylbenz[a]anthracene. Carcinogenesis. 1991 Feb;12(2):339–347. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y. J., Liem A., Miller E. C., Miller J. A. Metabolic activation of the carcinogen 6-hydroxymethylbenzo[a]pyrene: formation of an electrophilic sulfuric acid ester and benzylic DNA adducts in rat liver in vivo and in reactions in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1989 Aug;10(8):1519–1528. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.8.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y. J., Liem A., Miller E. C., Miller J. A. The strong hepatocarcinogenicity of the electrophilic and mutagenic metabolite 6-sulfooxymethylbenzo[a]pyrene and its formation of benzylic DNA adducts in the livers of infant male B6C3F1 mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Oct 15;172(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannheimer S. L., Barton S. L., Ethier S. P., Burchiel S. W. Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons increase intracellular Ca2+ and cell proliferation in primary human mammary epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997 Jun;18(6):1177–1182. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosko J. E. Challenge to the simple paradigm that 'carcinogens' are 'mutagens' and to the in vitro and in vivo assays used to test the paradigm. Mutat Res. 1997 Feb 3;373(2):245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosko J. E., Chang C. C., Madhukar B. V., Klaunig J. E. Chemical, oncogene and growth factor inhibition gap junctional intercellular communication: an integrative hypothesis of carcinogenesis. Pathobiology. 1990;58(5):265–278. doi: 10.1159/000163596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosko J. E., Chang C. C., Madhukar B. V. The role of modulated gap junctional intercellular communication in epigenetic toxicology. Risk Anal. 1994 Jun;14(3):303–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1994.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosko J. E., Chang C. C., Medcalf A. Mechanisms of tumor promotion: potential role of intercellular communication. Cancer Invest. 1983;1(6):511–526. doi: 10.3109/07357908309020276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosko J. E., Madhukar B. V., Chang C. C. Endogenous and exogenous modulation of gap junctional intercellular communication: toxicological and pharmacological implications. Life Sci. 1993;53(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao M. S., Smith J. D., Nelson K. G., Grisham J. W. A diploid epithelial cell line from normal adult rat liver with phenotypic properties of 'oval' cells. Exp Cell Res. 1984 Sep;154(1):38–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upham B. L., Kang K. S., Cho H. Y., Trosko J. E. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits gap junctional intercellular communication in glutathione sufficient but not glutathione deficient cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997 Jan;18(1):37–42. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upham B. L., Masten S. J., Lockwood B. R., Trosko J. E. Nongenotoxic effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their oxygenation by-products on the intercellular communication of rat liver epithelial cells. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994 Oct;23(3):470–475. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upham B. L., Weis L. M., Rummel A. M., Masten S. J., Trosko J. E. The effects of anthracene and methylated anthracenes on gap junctional intercellular communication in rat liver epithelial cells. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996 Dec;34(2):260–264. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Duuren B. L., Goldschmidt B. M. Cocarcinogenic and tumor-promoting agents in tobacco carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976 Jun;56(6):1237–1242. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchetich P. J., Bagchi D., Bagchi M., Hassoun E. A., Tang L., Stohs S. J. Naphthalene-induced oxidative stress in rats and the protective effects of vitamin E succinate. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21(5):577–590. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. S., Busby W. F., Jr Induction of lung and liver tumors by fluoranthene in a preweanling CD-1 mouse bioassay. Carcinogenesis. 1993 Sep;14(9):1871–1874. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.9.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T., Ishizuka T., Isobe M., Ozawa N. A 7-hydroxymethyl sulfate ester as an active metabolite of 7,12-dimethylbenz[alpha]anthracene. Science. 1982 Jan 22;215(4531):403–405. doi: 10.1126/science.6800033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H., Naus C. C. Role of connexin genes in growth control. Carcinogenesis. 1996 Jun;17(6):1199–1213. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.6.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ramos K. S. The induction of proliferative vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypes by benzo[a]pyrene does not involve mutational activation of ras genes. Mutat Res. 1997 Feb 3;373(2):285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Fouly M. H., Trosko J. E., Chang C. C. Scrape-loading and dye transfer. A rapid and simple technique to study gap junctional intercellular communication. Exp Cell Res. 1987 Feb;168(2):422–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]