Abstract

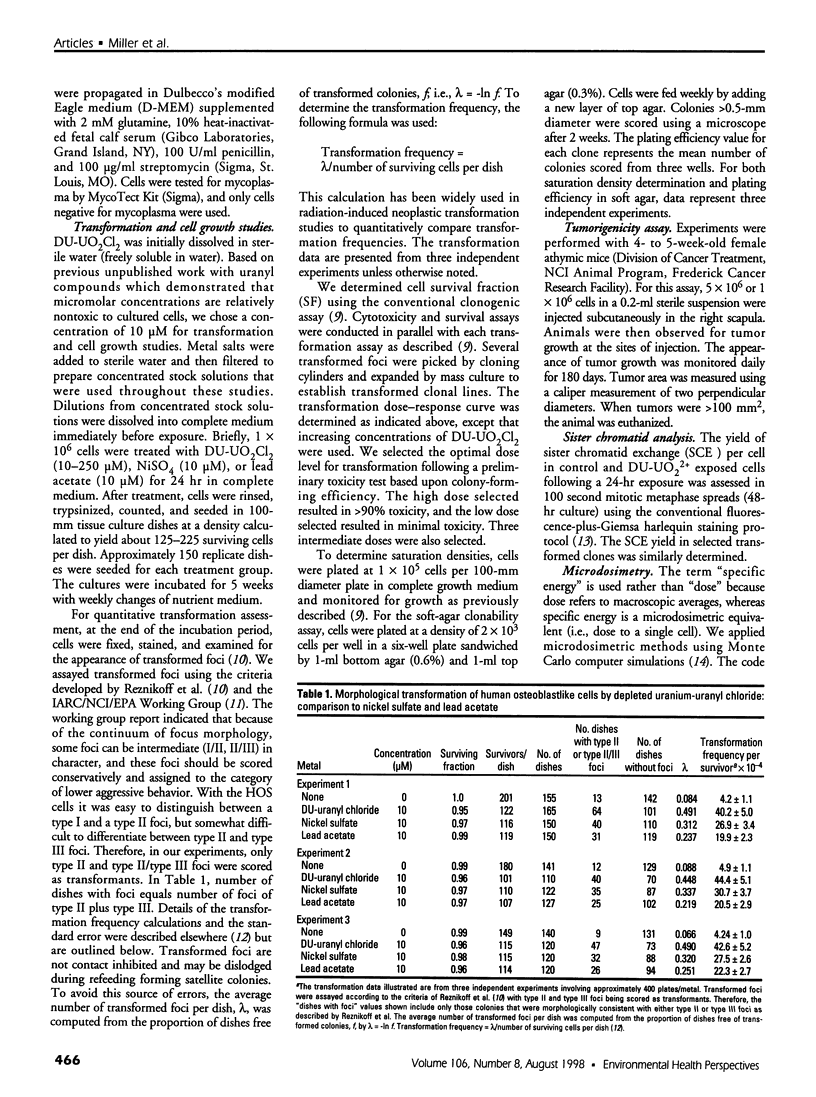

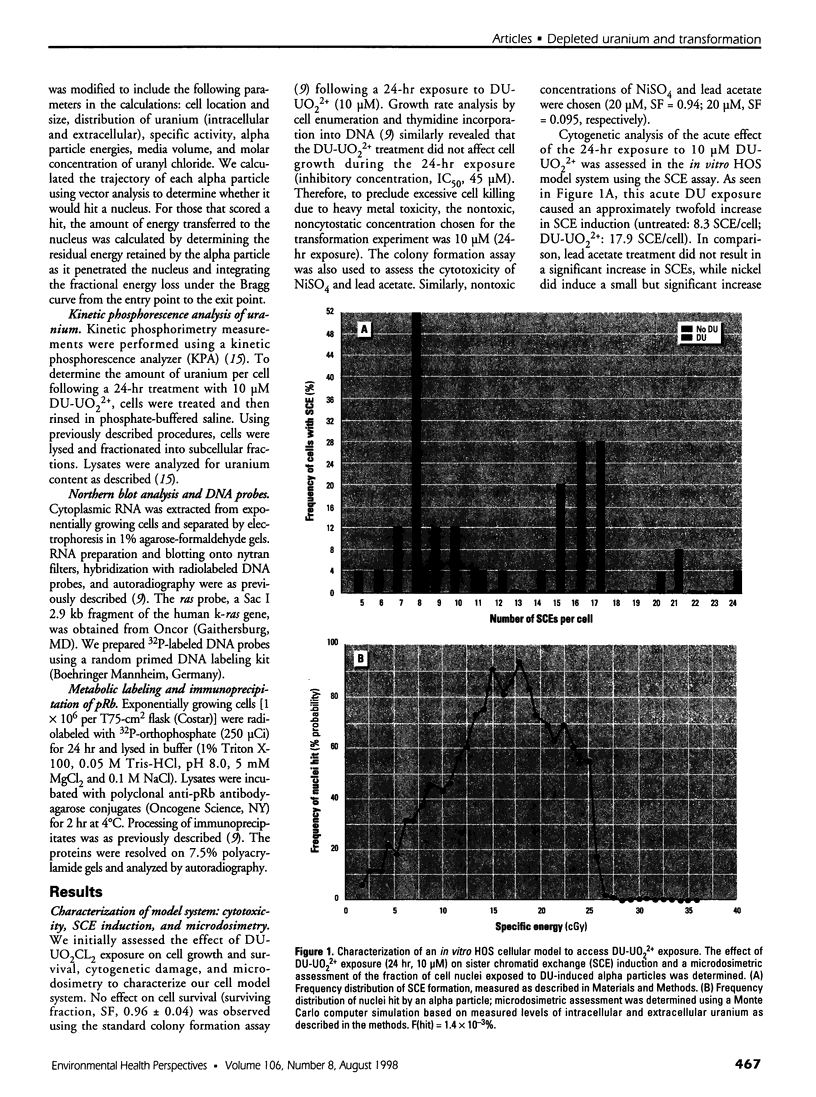

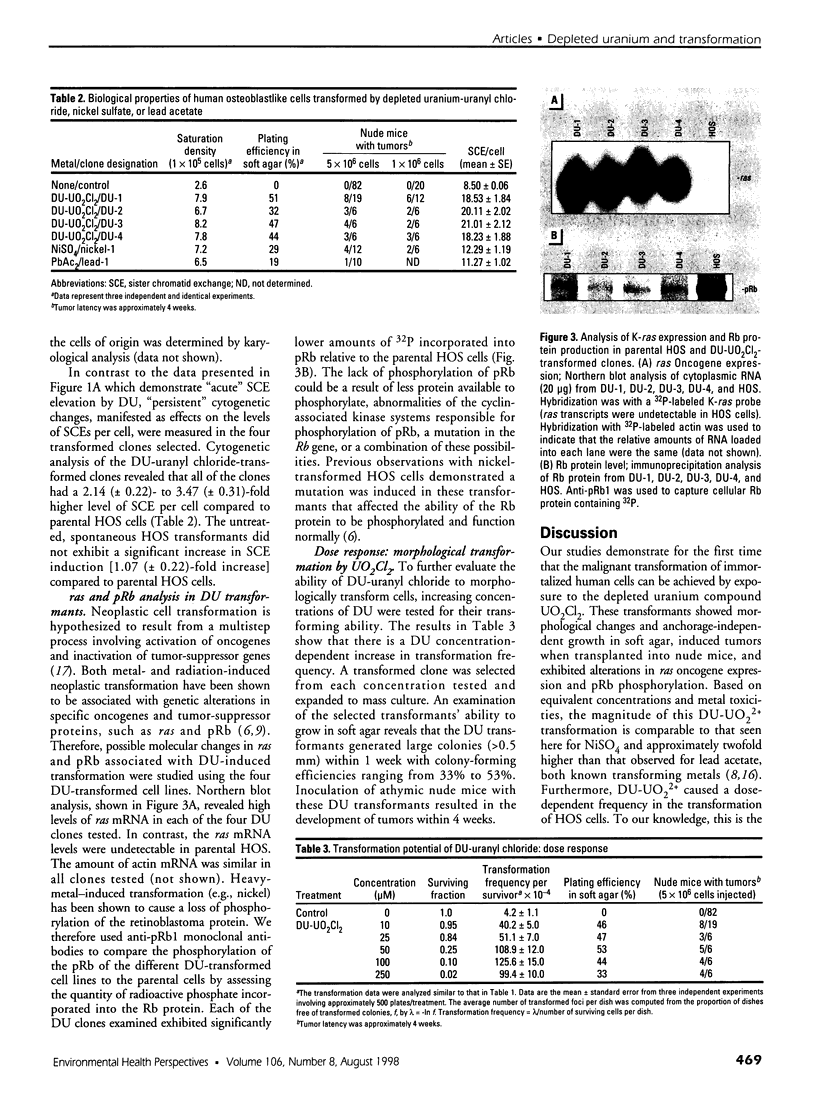

Depleted uranium (DU) is a dense heavy metal used primarily in military applications. Although the health effects of occupational uranium exposure are well known, limited data exist regarding the long-term health effects of internalized DU in humans. We established an in vitro cellular model to study DU exposure. Microdosimetric assessment, determined using a Monte Carlo computer simulation based on measured intracellular and extracellular uranium levels, showed that few (0.0014%) cell nuclei were hit by alpha particles. We report the ability of DU-uranyl chloride to transform immortalized human osteoblastic cells (HOS) to the tumorigenic phenotype. DU-uranyl chloride-transformants are characterized by anchorage-independent growth, tumor formation in nude mice, expression of high levels of the k-ras oncogene, reduced production of the Rb tumor-suppressor protein, and elevated levels of sister chromatid exchanges per cell. DU-uranyl chloride treatment resulted in a 9.6 (+/- 2.8)-fold increase in transformation frequency compared to untreated cells. In comparison, nickel sulfate resulted in a 7.1 (+/- 2.1)-fold increase in transformation frequency. This is the first report showing that a DU compound caused human cell transformation to the neoplastic phenotype. Although additional studies are needed to determine if protracted DU exposure produces tumors in vivo, the implication from these in vitro results is that the risk of cancer induction from internalized DU exposure may be comparable to other biologically reactive and carcinogenic heavy-metal compounds (e.g., nickel).

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barrett J. C. Mechanisms of multistep carcinogenesis and carcinogen risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 1993 Apr;100:9–20. doi: 10.1289/ehp.931009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely W. F., Fuciarelli A. F., Wegher B. J., Dizdaroglu M. Hydrogen peroxide-induced base damage in deoxyribonucleic acid. Radiat Res. 1990 Mar;121(3):338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycamp H. G., Luo D. Plutonium-catalyzed oxidative DNA damage in the absence of significant alpha-particle decay. Radiat Res. 1994 Jan;137(1):114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G. M. Cellular transforming genes. Science. 1982 Aug 27;217(4562):801–806. doi: 10.1126/science.6285471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero I., Villasante A., Corces V., Pellicer A. Activation of a c-K-ras oncogene by somatic mutation in mouse lymphomas induced by gamma radiation. Science. 1984 Sep 14;225(4667):1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.6474169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. K., Buonaguro F. M., Myers C. P., Han A., Elkind M. M. Fission-spectrum neutrons at reduced dose rates enhance neoplastic transformation. Nature. 1982 Jul 1;298(5869):67–69. doi: 10.1038/298067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humm J. L. A microdosimetric model of astatine-211 labeled antibodies for radioimmunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987 Nov;13(11):1767–1773. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadhim M. A., Macdonald D. A., Goodhead D. T., Lorimore S. A., Marsden S. J., Wright E. G. Transmission of chromosomal instability after plutonium alpha-particle irradiation. Nature. 1992 Feb 20;355(6362):738–740. doi: 10.1038/355738a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Costa M. Transformation of human osteoblasts to anchorage-independent growth by insoluble nickel particles. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Sep;102 (Suppl 3):289–292. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Dowjat W. K., Costa M. Nickel-induced transformation of human cells causes loss of the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. Cancer Res. 1994 May 15;54(10):2751–2754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manti L., Jamali M., Prise K. M., Michael B. D., Trott K. R. Genomic instability in Chinese hamster cells after exposure to X rays or alpha particles of different mean linear energy transfer. Radiat Res. 1997 Jan;147(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. C., Kariko K., Myers C. E., Clark E. P., Samid D. Increased radioresistance of EJras-transformed human osteosarcoma cells and its modulation by lovastatin, an inhibitor of p21ras isoprenylation. Int J Cancer. 1993 Jan 21;53(2):302–307. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910530222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan W. F., Day J. P., Kaplan M. I., McGhee E. M., Limoli C. L. Genomic instability induced by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 1996 Sep;146(3):247–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa H., Little J. B. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by extremely low doses of alpha-particles. Cancer Res. 1992 Nov 15;52(22):6394–6396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patierno S. R., Banh D., Landolph J. R. Transformation of C3H/10T1/2 mouse embryo cells to focus formation and anchorage independence by insoluble lead chromate but not soluble calcium chromate: relationship to mutagenesis and internalization of lead chromate particles. Cancer Res. 1988 Sep 15;48(18):5280–5288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry P., Wolff S. New Giemsa method for the differential staining of sister chromatids. Nature. 1974 Sep 13;251(5471):156–158. doi: 10.1038/251156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleskach N. M., Andriadze M. I., Mikhelson V. M., Zhestyanikov V. D. Sister chromatid exchanges and inhibition of DNA synthesis in irradiated human cells. Acta Biol Hung. 1990;41(1-3):209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A. S., Qu D. Q., Sidhu M. K., Panagakos F., Shah V., Klein K. M., Brown N., Pathak S., Kumar S. Transformation of immortal, non-tumorigenic osteoblast-like human osteosarcoma cells to the tumorigenic phenotype by nickel sulfate. Carcinogenesis. 1993 May;14(5):947–953. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikoff C. A., Bertram J. S., Brankow D. W., Heidelberger C. Quantitative and qualitative studies of chemical transformation of cloned C3H mouse embryo cells sensitive to postconfluence inhibition of cell division. Cancer Res. 1973 Dec;33(12):3239–3249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim J. S., Jin S., Jung M., Thraves P. J., Kuettel M. R., Webber M. M., Hukku B. Malignant transformation of human prostate epithelial cells by N-nitroso-N-methylurea. Cancer Res. 1997 Feb 15;57(4):576–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roarty J. D., McLean I. W., Zimmerman L. E. Incidence of second neoplasms in patients with bilateral retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 1988 Nov;95(11):1583–1587. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)32971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano J. W., Ehrhart J. C., Duthu A., Kim C. M., Appella E., May P. Identification and characterization of a p53 gene mutation in a human osteosarcoma cell line. Oncogene. 1989 Dec;4(12):1483–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawey M. J., Hood A. T., Burns F. J., Garte S. J. Activation of c-myc and c-K-ras oncogenes in primary rat tumors induced by ionizing radiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Feb;7(2):932–935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen P., Costa M. Induction of chromosomal damage in Chinese hamster ovary cells by soluble and particulate nickel compounds: preferential fragmentation of the heterochromatic long arm of the X-chromosome by carcinogenic crystalline NiS particles. Cancer Res. 1985 May;45(5):2320–2325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderman F. W., Jr Recent advances in metal carcinogenesis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1984 Mar-Apr;14(2):93–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vähäkangas K. H., Samet J. M., Metcalf R. A., Welsh J. A., Bennett W. P., Lane D. P., Harris C. C. Mutations of p53 and ras genes in radon-associated lung cancer from uranium miners. Lancet. 1992 Mar 7;339(8793):576–580. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg R. A. Tumor suppressor genes. Science. 1991 Nov 22;254(5035):1138–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1659741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn M. E., Durbin P. W., Howard B., Lipsztein J., Rundo J., Still E. T., Willis D. L. Metabolism of ingested U and Ra. Health Phys. 1985 May;48(5):601–633. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikoff J. T., Li J. H., Hartwig A., Wang X. W., Costa M., Rossman T. G. Genetic toxicology of lead compounds. Carcinogenesis. 1988 Oct;9(10):1727–1732. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.10.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidenberg-Cherr S., Parks N. J., Keen C. L. Tissue and subcellular distribution of bismuth radiotracer in the rat: considerations of cytotoxicity and microdosimetry for bismuth radiopharmaceuticals. Radiat Res. 1987 Jul;111(1):119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]