Abstract

Neuronal cultures in vitro readily oxidized both D-[14C]glucose and l-[14C]lactate to 14CO2, whereas astroglial cultures oxidized both substrates sparingly and metabolized glucose predominantly to lactate and released it into the medium. [14C]Glucose oxidation to 14CO2 varied inversely with unlabeled lactate concentration in the medium, particularly in neurons, and increased progressively with decreasing lactate concentration. Adding unlabeled glucose to the medium inhibited [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2 only in astroglia but not in neurons, indicating a kinetic preference in neurons for oxidation of extracellular lactate over intracellular pyruvate/lactate produced by glycolysis. Protein kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation inactivates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which regulates pyruvate entry into the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Dichloroacetate inhibits this kinase, thus enhancing PDH activity. In vitro dichloroacetate stimulated glucose and lactate oxidation to CO2 and reduced lactate release mainly in astroglia, indicating that limitations in glucose and lactate oxidation by astroglia may be due to a greater balance of PDH toward the inactive form. To assess the significance of astroglial export of lactate to neurons in vivo, we attempted to diminish this traffic in rats by administering dichloroacetate (50 mg/kg) intravenously to stimulate astroglial lactate oxidation and then examined the effects on baseline and functionally activated local cerebral glucose utilization (lCMRglc). Dichloroacetate raised baseline lCMRglc throughout the brain and decreased the percent increases in lCMRglc evoked by functional activation. These studies provide evidence in support of the compartmentalization of glucose metabolism between astroglia and neurons but indicate that the compartmentalization may be neither complete nor entirely obligatory.

Glucose is an essential and normally almost exclusive substrate for cerebral energy metabolism (1). As in other tissues, it is metabolized in brain in two sequential pathways, first to pyruvate/lactate by glycolysis in cytosol, followed by oxidation in mitochondria to CO2 and H2O. It was recently proposed that the glycolytic and oxidative components of glucose and glycogen metabolism are compartmentalized not only between cytosol and mitochondria but also between astroglia and neurons, i.e., glucose and glycogen metabolism in astroglia to lactate, which is then exported to neurons where it is oxidized to provide the ATP needed for neuronal function (2, 3). Arguments in support of this hypothesis are: (i) capillaries in brain are largely enveloped by astroglial processes that present a barrier to the transport of glucose from blood to neurons; (ii) glycogen in brain is confined almost entirely to astrocytes; (iii) astrocytes in culture readily metabolize glucose to lactate and release it into the medium (4, 5); and (iv) glutamate, the most prevalent excitatory neurotransmitter in brain, stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cultured astrocytes (6, 7). Much of the evidence supporting the hypothesis is based on in vitro studies with cells in culture. To our knowledge, the only study supporting such compartmentalization in mammalian brain in vivo is one in which NMR spectroscopy demonstrated an almost 1:1 stoichiometry between glucose utilization and the astroglial energy-consuming processes of glutamate uptake and conversion to glutamine (8).

In the present study, we compared biochemical properties of cultured neurons and astroglia that relate to their metabolism of glucose and lactate. The results confirm earlier observations (4, 5) that, under aerobic conditions, astroglia metabolize glucose to lactate far in excess of its rate of oxidation, resulting in extensive lactate release into the medium. They further show that astroglia have a limited capacity to oxidize glucose and lactate to CO2, whereas neurons readily oxidize both to CO2 but appear to prefer to oxidize lactate from the external medium over intracellular pyruvate/lactate produced by glycolysis. The possibility was considered that astroglial oxidation of pyruvate/lactate was limited by restricted pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH; EC 1.2.4.1) activity. This enzyme is a highly regulated component of the pyruvic dehydrogenase complex that metabolizes pyruvate to acetylCoA, a process that can limit the rate of entry of pyruvate carbon into the tricarboxylic acid cycle. We therefore examined the effects of dichloroacetate, a known activator of PDH activity, on lactate release and oxidation of glucose and lactate to CO2 by neurons and astroglia. Dichloroacetate stimulated glucose and lactate oxidation to CO2 considerably more in astroglia than in neurons and diminished lactate release by astroglia. To assess the possible functional significance of the lactate shuttle from astroglia to neurons in vivo, we attempted to reduce this transport by stimulating astroglial oxidation of pyruvate by dichloroacetate administration and examined its effects on gross behavior and baseline and functionally activated local cerebral glucose utilization (lCMRglc) in unanesthetized rats. Dichloroacetate administration had little, if any, effect on overall behavior, but increased lCMRglc in almost all areas of the brain and reduced percent increases in lCMRglc evoked by functional activation of a sensory pathway.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Chemicals and materials were obtained from the following sources: d-[U-14C]glucose (specific activity, 260 mCi/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) and l-[U-14C]lactate (specific activity, 181 mCi/mmol) from Perkin–Elmer Life Sciences (Boston); high-glucose (25 mM) DMEM, penicillin, and streptomycin from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD); defined FBS from HyClone; Dulbecco's PBS, poly-l-lysine, cytosine arabinoside, lactic dehydrogenase, and dichloroacetic acid (99+%) from Sigma; vimentin from Roche Molecular Biochemicals; glial fibrillary acidic protein from DAKO; and bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent from Pierce.

Animals.

All procedures on animals were in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee. Cell cultures were prepared from timed pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats (Taconic Farms). lCMRglc was measured in normal adult male 350- to 400-g Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Breeding Laboratories), maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with humidity and temperature controlled at normal levels and allowed food and water ad libitum until 16 h before experiments, when only food was removed.

Cell Cultures.

Neuronal and astroglial cultures were prepared from mesencephalon of fetal rats on embryonic day 16. The mesencephalon was excised and, after removal of meninges and blood vessels, mechanically disrupted by gentle passage through a 22-gauge needle. Neuronal cultures were prepared by dispersion of the dissociated cells (1.5 × 106 cells per ml) in poly-l-lysine-coated 25-cm2 culture flasks (Nalge Nunc) and incubation in high-glucose (25 mM) DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in humidified air containing 7% CO2. After 3 days of incubation, cytosine arabinoside (20 μM) was added to the culture medium. Assays were done on 8-day-old cultures. Astroglial cultures were prepared by dispersion of the dissociated cells (5 × 105 cells per ml) in uncoated 25-cm2 culture flasks and incubation under the same conditions, except no cytosine arabinoside was added, and the culture medium was changed on day 2 and every third day thereafter. Assays were done on 15-day-old cultures.

Some cells from the neuronal and astroglial cultures were plated in six-well culture plates for immunohistological examination. Neurons were stained with monoclonal antibodies against Neurofilament 68-kDa (Sigma) and 160-kDa (Chemicon) proteins. Astroglia were identified by antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin. More than 99% of the cells in the cultures showed the immunohistological character of the targeted cells.

Assay of Glucose and Lactate Oxidation to CO2 by Neuronal and Astroglial Cells.

Immediately before starting the assay, cultures were washed twice with 1 ml of Dulbecco's PBS at room temperature. One of the following reaction mixtures prewarmed to 37°C was then added to the culture flasks: (i) 2.5 mM d-[U-14C]glucose containing 0, 0.5, 2, or 4 mM unlabeled l-lactate; (ii) 2 mM l-[U-14C]lactate containing 0, 2.5, or 5 mM d-glucose; (iii) 2 mM d-[U-14C]glucose containing 0 or 100 μM dichloroacetate; or (iv) 2 mM l-[U-14C]lactate containing 0 or 100 μM dichloroacetate. Dichloroacetate solutions were adjusted to pH 7 with 1 M NaOH before addition to reaction mixtures. In addition, each reaction mixture contained 140 mM NaCl, 16 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 mM KCl and had been adjusted to pH 7.4. The culture flasks were then capped with rubber stoppers fitted with hanging wells containing accordion-folded, 1.5 × 2.5 cm pieces of filter paper that had been wetted with 100 μl of 1.0 M NaOH to trap 14CO2 produced. The culture flasks were incubated for 60 min in a 37°C water bath with gentle shaking. The reactions were terminated by injection of 250 μl of 60% (wt/vol) perchloric acid through the rubber stopper, and the flasks were kept at 4°C overnight to trap the 14CO2. The hanging wells including the filter paper were then transferred to 20-ml glass scintillation vials, and 250 μl of water and 10 ml of CytoScint (ICN) were added. 14C in the vials was assayed by liquid scintillation counting with external calibration (TriCarb Model 220CA; Packard, Downers Grove, IL). Cell carpets left in the incubation flasks after removal of the reaction mixtures were digested with 1 ml of 1 M NaOH, and their protein contents were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (9).

Assay of Lactate Production.

Lactate release into the medium was determined when glucose was a metabolic substrate in the above assays. After removal of the hanging wells from the flasks, the acidified reaction mixtures were withdrawn and adjusted to pH 6–7 with 5.0 M K2CO3. The precipitates were removed by centrifugation, and 20-μl samples of the supernatant solutions were added to cuvettes containing 500 μl of water, 400 μl of 1.0 M glycine buffer (pH 9.5), 50 μl of 0.56 M hydrazine sulfate (pH 8.6), and 20 μl of 0.1 M NAD+ (pH 6.75). After equilibration in the cuvettes for 5 min at room temperature, 10 μl (2.7 units/μl) of lactic dehydrogenase was added, and NAD+ reduction to NADH was followed by measurement of absorbance at 340 nm in a Beckman DU 650 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) until completion of the reaction. Lactate contents in the samples were calculated from the changes in absorbance and the specific absorbance of NADH at 340 nm.

Determination of lCMRglc in Vivo.

Rats were prepared for determination of lCMRglc by insertion of PE-50 catheters (Clay-Adams, Parsippany, NJ) into both femoral arteries and one femoral vein under halothane anesthesia (5% for induction and 1.0–1.5% for maintenance in 70% N2O/30% O2). Lidocaine ointment (5%) was applied to the surgical wounds after closure, and loose-fitting plaster casts were applied to the lower torso to minimize locomotion. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C throughout the procedure by a servo-controlled infrared lamp connected to a rectal thermistor probe. At least 3 h were allowed for recovery from surgery and anesthesia before initiation of lCMRglc determinations.

lCMRglc was determined by the quantitative autoradiographic 2-[14C]deoxyglucose (2-deoxy-d-[14C]glucose, 2-[14C]DG) method (10); the 2-[14C]DG dose was 125 μCi/kg and the experimental period 45 min. The frozen brain sections were autoradiographed together with calibrated [14C]methylmethacrylate standards on Kodak EMC-1 x-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). The autoradiograms were digitized in a Howtek MultiRAD 850 scanner (Howtek, Hudson, NH) and displayed on a computer monitor. Local tissue 14C concentrations were determined from the relationship between the 14C concentrations and optical densities in autoradiographic representations of the calibrated standards. lCMRglc was calculated from the tissue 14C concentrations and the time courses of arterial plasma glucose and 2-[14C]DG concentrations according to the operational equation of the method (10) and the computer program developed by G. Mies (Max-Planck-Institut für Neurologische Forschung, Cologne, Germany) for use with the nih image program (W. Rasband, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda) for image processing with a Macintosh computer. lCMRglc was determined in a variety of brain structures seen in the autoradiograms and identified by comparison with the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (11).

lCMRglc was determined in saline-treated control (n = 9) and dichloroacetate-treated rats (n = 6) at rest and bilaterally in four stations of the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway in control (n = 8) and dichloroacetate-treated (n = 7) rats during unilateral vibrissal stimulation. In the stimulated rats, whiskers on the right side of the face were clipped to minimize spurious stimulation on the control side, and the vibrissae on the left side were stroked with a soft brush at a frequency of two to three strokes per second throughout the 45-min period of lCMRglc measurement. Dichloroacetic acid, dissolved in normal saline (50 mg/ml) and adjusted to pH to 7.0–8.0 with 1 M NaOH, was infused (50 mg/kg) intravenously over a 5-min period; control rats were infused with equivalent volumes of saline. Measurement of lCMRglc was begun 4 h after infusion.

Several physiological variables relevant to cerebral energy metabolism were measured in all rats. Mean arterial blood pressure was measured with a Digi-Med Blood Pressure Analyzer (Model 300, MicroMed, Louisville, KY). Arterial blood pCO2, pO2, and pH were determined with a pH/blood gas analyzer (Model 288, Ciba Corning Diagnostics, Medfield, MA). Arterial plasma glucose concentration was measured in a Beckman Glucose Analyzer 2 (Beckman Instruments).

Statistical Analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SEM. In the studies with cell cultures the effects of dichloroacetate on glucose or lactate oxidation to CO2 and on lactate release into the medium were evaluated by paired t tests. Effects of dichloroacetate in neurons and astroglia were compared by unpaired t tests applied to the logarithms of the percent differences in glucose or lactate oxidation to CO2 and lactate release between control and dichloroacetate-treated cells. In the rat studies, in vivo physiological variables in dichloroacetate-treated and control groups were compared by unpaired t tests. The effects of dichloroacetate on resting lCMRglc in 18 brain structures were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t tests for each structure in which the ANOVA showed a significant difference. In the experiments on the effects of dichloroacetate on functional activation of lCMRglc, percent differences in lCMRglc between stimulated and unstimulated sides were calculated for each of the four structures of the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway, and the differences in the means of the logarithms of these individual percent differences in control and dichloroacetate-treated groups were compared by unpaired t tests with Bonferroni corrections.

Results

Glucose and Lactate Oxidation to CO2 in Neurons and Astroglia in Vitro.

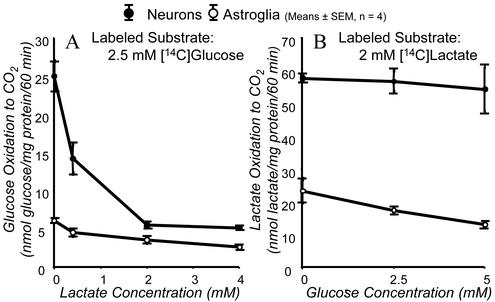

Rates of [14C]glucose and [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2 were determined with each labeled substrate added to the external medium alone or together with varying concentrations of the unlabeled species of the other. [14C]Glucose oxidation to 14CO2 in the absence of added unlabeled lactate was almost five times greater in neurons than in astroglia (Fig. 1A), and [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2 in the absence of unlabeled glucose was almost three times greater in neurons than in astroglia (Fig. 1B). Increasing concentrations of unlabeled lactate in the medium progressively reduced neuronal [14C]glucose oxidation to 14CO2 to rates almost as low as those in astroglia in which added unlabeled lactate had little effect on the already low rate of [14C]glucose oxidation to 14CO2 (Fig. 1A). Conversely, raising extracellular glucose concentration had no effect on [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2 in neurons but progressively diminished the rate in astroglia (Fig. 1B). It is noteworthy that with glucose and lactate concentrations in the extracellular medium close to those normally present in cerebral extracellular fluid in vivo (e.g., 2.5 and 2 mM, respectively), neurons oxidized [14C]lactate to 14CO2 10 times more rapidly than [14C]glucose, i.e., 57 ± 3 compared with 5.5 ± 0.4 nmol/mg protein/60 min (means ± SEM, n = 4) (Fig. 1 A and B), whereas in astroglia rates of [14C]glucose and [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2 were only 3.6 ± 0.3 and 17 ± 1 nmol/mg protein/60 min, respectively. These results indicate: (i) neurons oxidize both glucose and lactate to CO2 much more effectively than astroglia; (ii) both neurons and astroglia oxidize externally provided lactate to CO2 better than externally supplied glucose; (iii) neurons exhibit a kinetic preference for oxidation of externally supplied lactate over pyruvate/lactate produced intracellularly by glycolysis, a preference stronger than that shown by astroglia.

Figure 1.

Glucose and lactate oxidation to CO2 by neurons and astroglia in vitro. Cultured cells were incubated with either 2.5 mM D-[U-14C]glucose and various concentrations of unlabeled l-lactate (A) or 2 mM l-[U-14C]lactate and various concentrations of unlabeled D-glucose (B). Each point and associated error bar represent mean ± SEM of four experiments, in each of which value were determined in quadruplicate.

Effects of Dichloroacetate on Neuronal and Astroglial Glucose and Lactate Metabolism in Vitro.

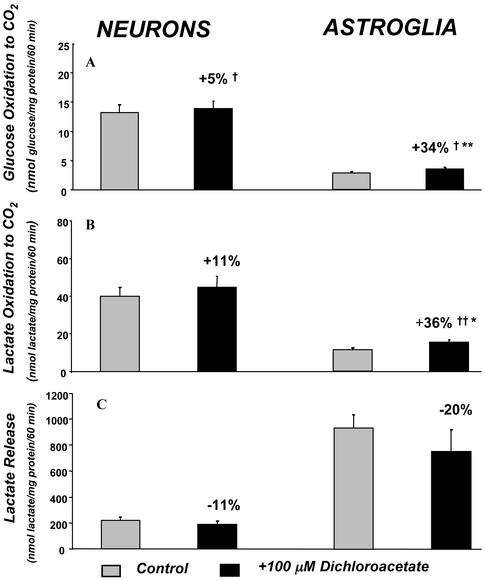

Addition of 100 μM dichloroacetate to the reaction medium had small effects on [14C]glucose oxidation (+5%, P < 0.05) and [14C]lactate oxidation (11%, statistically insignificant) to 14CO2 by cultured neurons (Fig. 2 A and C). In astroglia, which normally oxidized both substrates to CO2 more slowly than neurons (Fig. 2 A and B), dichloroacetate stimulated both rates statistically significantly, i.e., [14C]glucose oxidation (+34%, P < 0.01) and [14C]lactate oxidation (+36%, P < 0.01), both proportionately more than in neurons (Fig. 2 A and B).

Figure 2.

Effects of 100 μM dichloroacetate on rates of glucose and lactate oxidation to CO2 and lactate release into extracellular medium by neurons and astroglia in vitro. Bar heights and error bars represent mean rates ± SEM of glucose oxidation to CO2 (A), lactate oxidation to CO2 (B), or lactate release (C) determined in four experiments, in each of which each point was determined in quadruplicate. †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01, for comparison of absolute differences between control and dichloroacetate-treated groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, for comparisons between the logarithms of the percent differences between control and dichloroacetate-treated groups; the percent differences are the means of the individual percent differences in the experiments and not the percent difference between the means.

In agreement with previous reports (4, 5), astroglia released large amounts of lactate into the medium, i.e., 922 ± 104 nmol/mg protein per 60 min, a rate ≈100 times their rate of glucose oxidation to CO2 (Fig. 2 A and C). Neurons also released some lactate, i.e., 220 ± 28 nmol/mg protein per 60 min, a rate about one-fourth that of astroglia (Fig. 2C). Stimulating PDH activity with dichloroacetate reduced lactate release from both neurons (−11%) and astroglia (−20%) (Fig. 2C).

Effects of Dichloroacetate on Resting and Functionally Activated lCMRglc in Vivo.

The results of the studies with the cells in vitro were consistent with the hypothesis that astroglia first metabolize glucose to lactate and export it to neurons for oxidation. To examine whether such compartmentalization had any functional significance in vivo, we administered dichloroacetate to conscious rats to stimulate astroglial pyruvate/lactate oxidation to CO2 and thus reduce astroglial release of lactate and measured its effects on resting and functionally activated lCMRglc. Dichloroacetate treatment had little effect on gross behavior, possibly a slight sedative effect, but it lowered arterial plasma lactate levels from 1.4 ± 0.1 (mean ± SEM) to 1.0 ± 0.1 mM (−29%, P < 0.01) and arterial plasma glucose levels from 7.1 ± 0.2 to 6.2 ± 0.2 (−13%, P < 0.01) and from 7.2 ± 0.3 to 5.9 ± 0.2 (−18%, P < 0.01) in those series of rats in which these variables were measured (Table 1). Dichloroacetate had no statistically significant effects on any other physiological variables, except for a slight (−7%) reduction (P < 0.01) in mean arterial blood pressure in those rats in which only resting lCMRglc was measured (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiological variables in rats in two series of studies on effects of dichloroacetate in vivo

| Variable | Resting ICMRglc

|

Functional activation of ICMRglc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline controls (n = 9) | Dichloroacetate (50 mg/kg) (n = 6) | Saline controls (n = 8) | Dichloroacetate (50 mg/kg) (n = 7) | |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mm Hg | 122 ± 2 | 115 ± 2* | 122 ± 2 | 117 ± 2 |

| Arterial pCO2, mm Hg | 37 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 |

| Arterial pO2, mm Hg | 80 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 | 87 ± 2 | 87 ± 3 |

| Arterial pH | 7.45 ± 0.01 | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 7.46 ± 0.01 | 7.44 ± 0.01 |

| Arterial plasma glucose concentration, mM | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.2** | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 0.2** |

| Arterial plasma lactate concentration, mM | ND | ND | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1** |

Values are means ± SEM of number (n) of animals indicated. ND, not determined.

, P < 0.05;

, P < 0.01 compared to saline-treated controls.

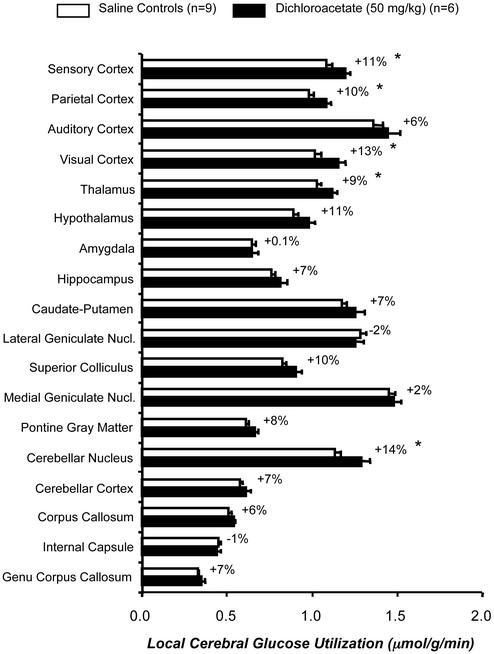

Dichloroacetate treatment tended to raise baseline lCMRglc throughout the brain. Although statistically significant (P < 0.05) in only five, increases were found in 16 of the 18 structures outside the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway examined (Fig. 3) and in all four structures (three statistically significantly, P < 0.05), within the pathway (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of dichloroacetate (50 mg/kg) administration on lCMRglc in representative structures of the brain in unanesthetized rats. Bar lengths and error bars represent means ± SEM obtained in the number of rats indicated. Values next to filled bars are the mean percent differences in lCMRglc between saline-treated control and dichloroacetate-treated groups. *, P < 0.05, for comparison of differences between control and dichloroacetate-treated groups.

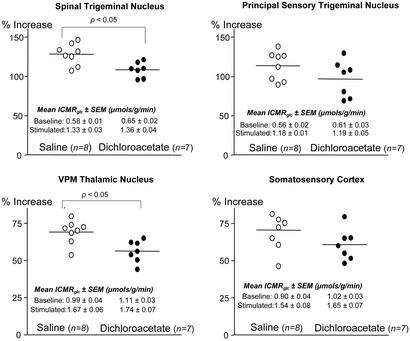

In the studies on dichloroacetate effects on functional activation of lCMRglc, unilateral vibrissal stimulation markedly increased lCMRglc in the ipsilateral spinal and principal trigeminal nuclei and contralateral ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus (VPM thalamic nucleus) and sensory cortex (Fig. 4). These percent increases in lCMRglc due to vibrissal stimulation were statistically significantly (P < 0.05) reduced by dichloroacetate in the spinal trigeminal nucleus and VPM thalamic nucleus (Fig. 4). Comparable, although statistically insignificant, reductions were also observed in the principal sensory trigeminal nucleus and somatosensory cortex (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of dichloroacetate (50 mg/kg) administration on functional activation of lCMRglc in four structures of the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway in unanesthetized rats. Points represent percent differences in lCMRglc between stimulated and unstimulated sides in each saline-treated control (○) and dichloroacetate-treated (●) rat. Bars represent the means of the individual percent differences in each group. P values are for comparison between saline-treated control and dichloroacetate-treated groups.

Discussion

It has been proposed, largely on the basis of observations in cultured cells, that the glycolytic and oxidative pathways of glucose metabolism in brain are compartmentalized not only within different subcellular elements but also between neurons and astroglia, i.e., uptake and metabolism of glucose to lactate in astroglia that then export the lactate to neurons for oxidation to CO2 and H2O (3). It was further proposed that this traffic is driven by synaptic activity and that the glycolytic rate has an almost 1:1 stoichiometry with the uptake of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and its conversion to glutamine in the astrocytes (6, 8, 12, 13). This hypothesis has met with considerable interest and controversy (14–16), but it is difficult to prove or disprove because of limited ability to examine glucose and lactate metabolism in neurons and astroglia separately in vivo. The goals of the present study were: (i) to ascertain whether neurons and astroglia in vitro possess properties vis-à-vis glucose and lactate metabolism that are consistent with such compartmentalization; (ii) to attempt to stimulate pyruvate oxidation by astroglia and thus diminish their lactate export; and (iii) to assess the importance of such compartmentalization to brain function in vivo by examining the effects of such diminished lactate transport on baseline and functionally activated lCMRglc in unanesthetized animals.

The results confirm that neurons and astroglia do have metabolic properties that favor the proposed intercellular compartmentalization. In agreement with previous reports (4, 5, 17–19), astroglia were found to metabolize glucose mainly to lactate and release it into the external medium and to have limited capacity to oxidize glucose or lactate to CO2 (Figs. 1 and 2). In contrast, neurons released less lactate into the medium and oxidized both [14C]glucose and [14C]lactate to 14CO2 far more rapidly than astroglia (Figs. 1 and 2). Of particular interest is the behavior of the cells when both glucose and lactate were present in the external medium. With astroglia, unlabeled lactate in the medium produced concentration-dependent reductions in [14C]glucose oxidation to 14CO2, and unlabeled glucose produced comparable reductions in [14C]lactate oxidation to 14CO2, indicating that pyruvate produced intracellularly by glycolysis and pyruvate derived from lactate in the extracellular medium were effectively competing with one another for oxidation. With neurons, however, unlabeled lactate in the medium also concentration-dependently reduced [14C]glucose oxidation to 14CO2, but unlabeled glucose in the medium had no effect on oxidation of extracellular [14C]lactate to 14CO2. Apparently, in neurons [14C]pyruvate produced intracellularly from [14C]glucose is more effectively diluted by unlabeled pyruvate derived from extracellular lactate than the [14C]pyruvate derived from extracellular [14C]lactate is by the unlabeled pyruvate produced intracellularly from unlabeled glucose. These results indicate that the flux of lactate from the external medium far exceeds the flux from glycolysis into the intracellular lactate/pyruvate pool and suggest that neurons have a kinetic preference to oxidize extracellular lactate over lactate/pyruvate derived from glycolysis.

Inhibition of [14C]glucose oxidation to 14CO2 by unlabeled extracellular lactate is not itself evidence that total glucose metabolism is reduced. It indicates only that extracellular lactate entering the cells dilutes and competes with the [14C]lactate/pyruvate produced by glycolysis for oxidation and has no relevance to the rate of glycolysis. Rapid influx of lactate from the medium, however, would almost certainly slow the rate of glycolysis because higher intracellular lactate concentrations shift the lactate dehydrogenase-catalyzed reaction equilibrium toward higher [NADH][H+]/[NAD+] ratios, which would slow the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphofructokinase reactions, rate-limiting steps in glycolysis.

Although the results indicate that neurons possess properties favoring the oxidation of lactate supplied by astroglia, they also suggest that neuronal metabolism of glucose can be regulated by extracellular lactate concentration. Lower extracellular lactate concentrations lead to lower intracellular lactate levels and, consequently, increased oxidation of pyruvate derived from glycolysis and probably also increased rates of glycolysis. It is noteworthy that when extracellular glucose and lactate concentrations were close to those existing in vivo under physiological conditions, neurons oxidized 10 times more lactate than glucose, but that ratio fell markedly with decreasing extracellular lactate concentrations.

Pyruvate entry into the tricarboxylic acid cycle and therefore its rate of oxidation are controlled by the highly regulated PDH enzyme complex. PDH, a key enzyme in this complex, is inactivated when phosphorylated by a specific PDH kinase and reactivated by dephosphorylation. Diisopropylammonium dichloroacetate was found to lower glucose levels in diabetic animals (20), and dichloroacetate was found to be the active moiety (21). Subsequently, dichloroacetate administration to perfused rat hearts was found to stimulate myocardial PDH activity by inhibiting its phosphorylation by PDH kinase (22, 23). The fraction of total PDH activity in the active dephosphorylated form in whole brain has been reported to be ≈70% (24) and to be increased by membrane depolarization but unaffected by dichloroacetate in rat brain synaptosomes (25). Abemayor et al. (26), however, found that dichloroacetate administration in vivo activated brain PDH activity, indicating that it crosses the blood–brain barrier, and dichloroacetate is now used clinically to lower elevated lactate levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mitochondrial disorders (27). In the present studies, dichloroacetate enhanced glucose and lactate oxidation to CO2 by astroglia and neurons in vitro, especially in astroglia, which normally have much lower rates (Fig. 2). This suggests that the fraction of total PDH in the inactive form is normally greater in astroglia than in neurons, a situation favoring lactate export from astroglia to neurons. It was probably for this reason that activating PDH with dichloroacetate reduced lactate release into the medium more in astroglia than in neurons (Fig. 2).

To assess whether the metabolic properties of neurons and astroglia observed in vitro were significant to brain function in vivo, we administered dichloroacetate to conscious rats and examined the effects on gross behavior and on lCMRglc at rest and during functional activation of the whisker-to-barrel cortex sensory pathway. The intentions were to diminish export of lactate by astroglia by stimulating their oxidation of pyruvate and to examine the effects on brain function and metabolism. The dose of dichloroacetate was sufficient to affect total body lactate metabolism because it lowered arterial plasma lactate levels by 29% (Table 1). Although dichloroacetate had little, if any, overt effect on gross behavior, it did raise baseline lCMRglc slightly to moderately in 16 of 18 (P < 0.05 in five) representative brain structures outside the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway and in all four structures within the pathway (P < 0.05 in three). Because it is unlikely that increasing pyruvate oxidation in astroglia would also stimulate their rate of glycolysis, the observed increases in baseline lCMRglc probably occurred in neurons as a result of reduced astroglial lactate release and lower extracellular lactate concentrations, which, according to the results in Fig. 1, would lead to increased oxidation of glucose and probably also glycolysis in neurons.

Although dichloroacetate tended to raise baseline lCMRglc, it lowered the percent increases evoked by vibrissal stimulation in all four stations of the whisker-to-barrel cortex pathway, statistically significantly (P < 0.05) in two, i.e., spinal trigeminal and ventral posteromedial nuclei of the thalamus (Fig. 4). The absolute rates of lCMRglc in the functionally activated sites were, however, at least as high as those in rats not treated with dichloroacetate, suggesting that the decreases in percent activation were probably due to the higher baseline rates that were already providing some of the additional ATP required by the functional activation.

Conclusion

Cultured neurons and astroglia possess metabolic properties that favor the proposed compartmentalization of glucose metabolism and the trafficking of lactate between them. Astroglia metabolize glucose mainly to lactate and release it into the extracellular medium, and neurons appear to have a kinetic preference for oxidizing lactate imported from the external medium over pyruvate/lactate produced intracellularly by glycolysis. Lactate oxidation in astroglia appears to be rate-limited, partly, if not entirely, at the PDH step and can be enhanced by activation of PDH activity by dichloroacetate. The results, however, also suggest that the compartmentalization may be neither complete nor obligatory. Astroglia have some capacity to oxidize glucose and lactate to CO2, and neurons, which in vivo are normally exposed to extracellular glucose concentrations of 2–3 mM, can metabolize glucose to CO2. The completeness of the compartmentalization may vary with the functional state. Reduction in extracellular lactate concentration, which in brain in vivo is normally about 1–2 mM, may lead to enhanced glucose oxidation by neurons, thus compensating for any reduction in lactate supply from astroglia. This is what may have occurred in vivo when dichloroacetate was administered to activate PDH and enhance lactate oxidation by astroglia, thus reducing their export of lactate; lCMRglc was increased, and normal function was essentially preserved. Increasing extracellular lactate concentrations inhibit glucose oxidation in neurons, and, during functional activation, when astroglial metabolism of glucose is increased for glutamate-glutamine cycling (8) and extracellular lactate concentrations rise (28), neurons may depend more on lactate derived from astroglial metabolism.

Abbreviations

- 2-[14C]DG

2-[14C]deoxyglucose, 2-deoxy-d-[1-14C]glucose

- lCMRglc

local cerebral glucose utilization

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

References

- 1.Clarke D D, Sokoloff L. In: Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular, and Medical Aspects. 6th Ed. Siegel G, Agranoff B, Albers R W, Fisher S, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven; 1999. pp. 637–669. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellerin L, Pellegri G, Bittar P G, Charnay Y, Bouras C, Martin J L, Stella N, Magistretti P J. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:291–299. doi: 10.1159/000017324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magistretti P J, Pellerin L. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1999;354:1153–1163. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walz W, Mukerji S. Glia. 1988;1:366–370. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna M C, Tildon J T, Stevenson J H, Boatright R, Huang S. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:320–329. doi: 10.1159/000111351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellerin L, Magistretti P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10625–10629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi S, Driscoll B F, Law M J, Sokoloff L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4616–4620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibson N R, Dhankhar A, Mason G F, Rothman D L, Behar K L, Shulman R G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:316–321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers M H, Patlak C S, Pettigrew K D, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 3rd Ed. San Diego: Academic; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellerin L, Magistretti P J. Dev Neurosci. 1996;18:336–342. doi: 10.1159/000111426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magistretti P J, Pellerin L, Rothman D L, Shulman R G. Science. 1999;283:496–497. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chih C-P, Lipton P, Roberts E L., Jr Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01920-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vannucci S J, Simpson I A. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:821–823. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dienel G A, Hertz L. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:824–838. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauwels P J, Opperdoes F R, Trouet A. J Neurochem. 1985;44:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes-Cardozo M, Larsson O M, Schousboe A. J Neurochem. 1986;46:773–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb13039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hertz L, Drejer J, Schousboe A. Neurochem Res. 1988;13:605–610. doi: 10.1007/BF00973275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorini M, Ciman M. Biochem Pharmacol. 1962;11:823–827. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(62)90177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stacpoole P W, Felts J M. Metabolism. 1970;19:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(70)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehouse S, Randle P J. Biochem J. 1973;134:651–665. doi: 10.1042/bj1340651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehouse S, Cooper R H, Randle P J. Biochem J. 1974;141:761–774. doi: 10.1042/bj1410761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siess E, Wittmann J, Wieland O. Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 1971;352:447–452. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1971.352.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffer W T, Olson M S. Biochem J. 1980;192:741–751. doi: 10.1042/bj1920741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abemayor E, Kovachich G B, Haugaard N. J Neurochem. 1984;42:38–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb09694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stacpoole P W, Barnes C L, Hurbanis M D, Cannon S L, Kerr D S. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:535–541. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.6.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prichard J, Rothman D, Novotny E, Petroff O, Kuwabara T, Avison M, Howseman A, Hanstock C, Shulman R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5829–5831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]