Abstract

The maize pathogen Ustilago maydis switches from budding to filamentous, dikaryotic growth in response to environmental signals including nutrient status, growth in the host, and the presence of mating pheromones. The filamentous dikaryon is capable of proliferating within host tissue to cause disease symptoms including tumors. The transition from yeast cells to hyphal filaments is regulated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and a cyclic-AMP-protein kinase A (PKA) pathway. Serial analysis of gene expression with PKA mutants identified orthologs of components of the PHO phosphate acquisition pathway as transcriptional targets of the PKA pathway, and these included genes for Pho84, an acid phosphatase, and the vacuolar transport chaperones Vtc1 and Vtc4. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Vtc4p is required during the fusion of inorganic-phosphate-containing vesicles to the vacuolar membrane and the consequent accumulation of phosphate stored as polyphosphate (polyP) in the vacuole. We found that deletion of vtc4 in U. maydis also reduced polyP stored in vacuoles. Intriguingly, Δvtc4 mutants possessed a filamentous cellular morphology, in contrast to the budding, yeast-like growth of the wild-type parent. The Δvtc4 mutants also displayed decreased symptom development and reduced proliferation in planta. The interaction with PKA signaling was further investigated by the generation of Δvtc4 ubc1 double mutants. Deletion of vtc4 completely suppressed the multiple-budded phenotype of a Δubc1 mutant, indicating that polyP stores are essential for this PKA-induced trait. Overall, this study reveals a novel role for PKA-regulated polyP accumulation in the control of fungal morphogenesis and virulence.

Plant infection by biotrophic fungi involves the establishment of interactions that require the living host for pathogen development and proliferation. The plant tissue provides both nutrients and signals for fungal growth and development. The basidiomycete fungus Ustilago maydis is a biotrophic pathogen of maize. During infection, haploid budding cells of opposite mating types extend conjugation tubes that fuse to form an infectious filamentous dikaryon (5, 15, 20). U. maydis infection results in the production of anthocyanin pigment and large tumors at sites of infection. The filamentous dikaryon proliferates within the tumors and differentiates into melanized teliospores that eventually emerge from ruptured plant tissue (3, 30, 31). Teliospores can disseminate onto new plants, where they can germinate by extending a basidium, undergo meiosis, and produce budding haploid progeny off the basidium to reinitiate the life cycle (7). Changes in morphology during the life cycle are regulated by two conserved pathways: a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade and a cyclic-AMP (cAMP)-protein kinase A (PKA) pathway (1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 24). Both pathways regulate the transition from budding to filamentous growth by transducing environmental signals such as nutrient availability, the presence of lipids, putative plant signals, acidic pH, exposure to air, and pheromones from mating cells of the opposite mating type (5, 6, 13, 18, 23).

Serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) was previously performed to compare the transcriptomes of wild-type cells versus the PKA mutants ubc1 and adr1 (22). Mutation of the ubc1 gene, encoding the regulatory subunit of PKA, results in a multibudded phenotype. Although ubc1 mutants can proliferate in planta, no tumor symptoms are observed upon infection (12). In contrast, mutation of adr1, encoding the catalytic subunit of PKA, results in a constitutively filamentous phenotype. The adr1 mutants also display reduced virulence in maize (9). SAGE revealed an interesting connection between PKA signaling and phosphate metabolism in U. maydis (22). Specifically, a number of tags for orthologs of components of the PHO phosphate acquisition pathway were elevated in the ubc1 library and/or reduced in the adr1 library. These included genes for the high-affinity phosphate permease Pho84, an acid phosphatase, and the vacuolar transporter chaperones Vtc1 and Vtc4, which are involved in polyphosphate (polyP) storage in the vacuole (22). Phosphate can influence the morphology of U. maydis in response to lipids, with increasing phosphate levels directly correlating with an increase in filamentation. It was also found that the ubc1 mutant possesses a reduced amount of stored polyP (22).

A connection between phosphate acquisition and the PKA pathway has also been established in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Specifically, it was shown that inorganic phosphate (Pi) is sensed by the Pho84p and Pho87p permeases and acts in concert with glucose as a nutrient signal to activate the PKA pathway (10). The majority of Pi is taken into S. cerevisiae cells by the high-affinity permease Pho84p, while the permeases Pho89p, Pho87p, Pho90p, and Pho91p play less significant roles (reviewed in reference 27). Excess intracellular Pi is stored in the vacuole as polyP, which is formed by high-energy phosphoanhydrous linkage of hundreds of Pi molecules. polyP represents a Pi reserve that can be utilized in times of Pi starvation and also plays a role in cation sequestration and storage, gene expression, and the response to stress and as an alternative energy source (ATP substitute) (reviewed in references 19 and 21). In addition to enzymes required for polyP synthesis and breakdown, the vacuolar transport chaperone proteins Vtc1p, Vtc2p, Vtc3p, and Vtc4p are also required for polyP accumulation in the vacuole because of the requirement for Pi-containing vesicles to fuse with the vacuolar membrane (25, 27).

The connection between PKA signaling and the transcription of genes required for phosphate acquisition and storage prompted us to further investigate the role of phosphate in the growth and virulence of U. maydis. In this report, we describe the deletion of the U. maydis vtc4 gene and the characterization of the resulting mutants. In particular, we show that Δvtc4 mutants have a filamentous morphology, in contrast to budding yeast-like cells of wild-type strains. This result reveals a direct connection between intracellular phosphate storage and the development of U. maydis into the infectious cell type. In addition, we show that vtc4 is essential for accumulation of polyP in the vacuole and that Δvtc4 strains exhibit decreased virulence in maize, with mutant cells failing to proliferate extensively within the host tissue. We also further characterized the connection between phosphate and the PKA pathway. Deletion of vtc4 suppresses the multibudded phenotype of the Δubc1 mutant and decreases budding in exogenous cAMP. Overall, this study revealed novel functions of vacuolar polyP in regulating both the morphology and virulence of U. maydis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated with the Eppendorf fast plasmid mini kit, and genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (4). Southern and Northern transfers were performed with Amersham Hybond N+ membranes in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and were hybridized by standard methods and [α-32P]dCTP (28).

The genomic sequence of vtc4 was obtained from the U. maydis genome sequence at http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/ustilago/ (Um06230). The Δvtc4::hygBR construct was generated by overlap PCR (8). Primers KB019 (P1, 5′ TGAGTTGGCAGGATCGTGAA 3′) and KB030 (P2P3C, 5′ AACTGTGCTTCAATCGCTGCTGCTGCACAAAGAGGAACGT 3′) and primers KB032 (P5P4C, 5′ TAGCACACGACTCACATCTGTTTGTTGGCATCGAGTCACG 3′) and KB020 (P6, 5′ ACAAGGATGGCGAAGAGGAG 3′) were used to amplify the 1,010-bp left arm and 1,067-bp right arm, respectively, of the genomic DNA. Primers KB029 (P2CP3, 5′ ACGTTCCTCTTTGTGCAGCAGCAGCGATTGAAGCACAGTT 3′) and KB031 (P4P5C, 5′ CGTGACTCGATGCCAACAAACAGATGTGAGTCGTGTGCTA 3′) amplified a 2.7-kb hygromycin resistance marker region from pIC19RHL. Overlap PCR was performed with the three PCR fragments as templates and the nested primers KB040 (5′ TGCTGTTCATGCTGGTCTCA 3′) and KB039 (5′ AGTGATGACGAGGATGGGGT 3′). The 4.7-kb overlap PCR product was cloned into TOPO-TA (Invitrogen), generating the Δvtc4::hygBR construct (pKB002). This construct deletes the region from −17 to +3400 relative to the ATG translation start codon (67 bp of the 3′ end) and has 844 bp and 943 bp of the flanking region on either side of the selectable marker for homologous recombination.

Strains.

The Δvtc4::hygBR a2b2 and Δvtc4::hygBR a1b1 strains were generated by biolistic transformation of strains a2b2 (518) and a1b1 (521) with pKB002. The Δvtc4::hygBR Δubc1::phleoR a2b2 strains were generated by transformation of strain 0505 (Δubc1-4::phleoR a2b2) (11) with pKB002. Transformants were selected on double complete medium (CM) with 1 M sorbitol and 250 μg/ml hygromycin B and purified on CM plates containing 150 μg/ml hygromycin B. Transformants were screened by colony PCR with a primer outside the construct (KB115, 5′ CGTGAATCAAGAATGGCA 3′) and a primer within hygB (KB030, 5′ AACTGTGCTTCAATCGCTGCTGCTGCACAAAGAGGAACGT 3′). Gene deletion and the absence of ectopic copies were confirmed by Southern blotting.

Media and growth conditions.

Analysis of haploid cell morphology was performed by growing strains 518 (a2b2), 521 (a1b1), Δvtc4::hygBR a1b1, Δvtc4::hygBR a2b2, and Δvtc4::hygBR Δubc1::pheloR a2b2 overnight at 30°C in CM plus 1% glucose, washing them once with distilled H2O (dH2O), and inoculating 1 × 106 cells into minimal medium minus phosphate (MM) plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 and incubating them overnight (18 h). Mating assays were performed on plates with CM and activated charcoal as previously described (14, 15).

Microscopic analysis.

For cell wall staining, 1 μl of the fluorescent brightener 28 Calcofluor White (CAL; 1 μg ml−1; Sigma) was added directly to 3 μl of cell culture on a slide. For polyP staining, 1 ml of overnight culture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 min, resuspended in 100% ethanol, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in 0.05% Toluidine Blue O, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Stained cells were washed four times in sterile dH2O (sdH2O) before microscopic observation. To observe the formation of mating filaments, filaments were scraped off a mating medium and resuspended in sdH2O plus 1 μl CAL. For analysis of the effect of exogenous cAMP, 1 × 106 cells were inoculated into MM plus 1% glucose and with 1, 5, or 10 mM cAMP or no cAMP (sodium salt; Sigma) and grown overnight at 30°C. Cells were viewed on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope under differential interference contrast (DIC) or UV fluorescence to observe CAL-stained walls. Images were captured with a DVC camera and processed with Northern Eclipse imaging software and Adobe Photoshop 7.

polyP extractions.

Cells for polyP extractions were grown overnight in CM, washed once with dH2O, and inoculated into MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4. These cells were then grown overnight or for 3.5 days. polyP was isolated during RNA isolation according to the Purescript RNA isolation protocol from Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN. A total of 10 μg of total RNA of each sample and 20 μg of polyP P25 or P45 as a ladder (named for the major polyP chain length; sodium phosphate glass type; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were loaded onto a 20% polyacrylamide gel. polyP was stained with Toluidine Blue O (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as described by Ogawa et al. (26).

Pathogenicity assays.

Strains a2b2 (518), a1b1 (521), Δvtc4::hygBR a1b1, and Δvtc4::hygBR a2b2 were grown in PDB medium overnight in a shaking incubator at 30°C. Cultures were diluted to 1 × 106 cells ml−1 and mixed in the following combinations: a2b2 (518)-a1b1 (521), a2b2 (518)-Δvtc4::hygBR a1b1, Δvtc4::hygBR a2b2-a1b1 (521), and Δvtc4::hygBR a2b2-Δvtc4::hygBR a1b1. One-week-old Zea mays (Golden Bantam) plants grown in a greenhouse (at temperatures ranging from 20 to 25°C) were inoculated by stem injection (26G1/2 needle) with approximately 100 μl of mating cultures. Plants were scored for disease after 2 weeks. Disease ratings were as follows: 0, no disease; 1, pigment production; 2, small leaf tumors; 3, small stem tumors; 4, large stem tumors and teliospore production; 5, plant death. Pathogenicity assays were performed on three separate occasions, and a minimum of 100 plants for each cross were scored for disease ratings. To assess teliospore production, approximately 2 ml of mating culture (1 × 106 cells ml−1) was injected into the silk channels of developing ears. Teliospore production was observed 3 weeks after inoculation.

In planta phenotypic analysis.

Epidermal peeling was performed on leaves at 6 days postinfection, and samples were placed on a 20-μl drop of water containing 3 μl CAL (1 μg ml−1). The infection procedure was as described above. Horizontal and vertical dissections of tumors isolated from infected plants 14 days postinfection were performed with a razor blade, and the samples obtained were also placed on a 20-μl drop of water containing 3 μl CAL.

Teliospore isolation and germination.

Tumors were isolated from infected corn plants 14 days postinfection (described above). Whole tumors were dipped in 10% bleach for 30 s, washed twice in sdH2O, and ground in 20 ml of a solution of 1.5% CuSO4 · 5H2O. Teliospore preparations were filtered through cheesecloth and incubated overnight at room temperature. Teliospore suspensions were centrifuged and washed twice in sdH2O. Subsequently, 200 μl of the teliospore preparation was spread over a petri dish containing a microscopic slide covered in ∼3 mm of 1.5% water agar. After approximately 14 h of incubation at 30°C, the slides were cut out of the petri dish and 1 μl of CAL in 5 μl sdH2O was placed onto the coverslip prior to inversion. Teliospores were isolated from three independent experiments, and germination was observed in three separate experiments.

RESULTS

Identification of the U. maydis vtc4 homolog.

SAGE analysis of the ubc1 and adr1 PKA mutants revealed that the transcript abundance of the U. maydis vtc4 (vacuolar transport chaperone 4) homolog was elevated approximately twofold in the Δubc1 mutant compared to the wild type (22; data not shown). The genomic sequence of the U. maydis vtc4 homolog (Um06230) was obtained from the genome sequence that is available at http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/ustilago/. The vtc4 gene encodes a predicted polypeptide of 833 amino acids with three putative transmembrane domains (amino acids 731 to 750, 757 to 779, and 794 to 816) and an SPX domain in the N-terminal region (amino acids 1 to 152). SPX domains are named after the Syg1, Pho81, and Xpr1 proteins and are found at the N termini of proteins involved in G-protein-associated signal transduction, as well as in proteins that sense phosphate levels. Vtc4 shows the highest sequence similarity to a hypothetical protein in Yarrowia lipolytica (66% identity and 80% similarity; accession number XP_501721) and shows high sequence similarity to Vtc4p in S. cerevisiae (64% identity and 78% similarity; accession number NP_012522).

Deletion of vtc4 confers a filamentous cellular morphology.

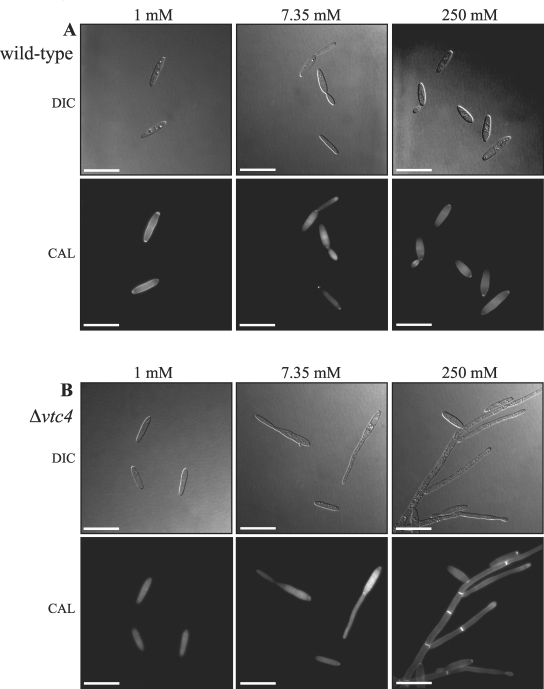

The coding region of the vtc4 gene was deleted in strains of the a1b1 and a2b2 mating types, and two deletion strains from each background were used in phenotypic analyses (see Materials and Methods). Colonies of the Δvtc4 strains appear indistinguishable from the wild type on MM with 1% glucose and 1 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 1). However, in contrast to the smooth colonial morphology of wild-type colonies grown on MM plus 1% glucose and either 7.35 or 250 mM KH2PO4, the Δvtc4 strains exhibit a filamentous morphology (Fig. 1). Filamentation of Δvtc4 colonies was enhanced with increasing KH2PO4 concentrations, with only a few small protrusions observed on 7.35 mM KH2PO4 and extensive filamentation observed on 250 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 1). To observe the cellular morphology of haploid cells, 1 × 106 cells of both the wild-type and Δvtc4 strains were inoculated into MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 and grown overnight. For reference, the standard U. maydis MM contains 7.35 mM KH2PO4. Wild-type U. maydis strains exhibited a budding morphology under these conditions, regardless of the phosphate level (Fig. 2A), and the number of wild-type budding cells increased with increasing phosphate concentrations (Table 1). The correlation between increased budding and phosphate concentrations might be expected because growth is slower in low-phosphate medium, such that cells take longer to fully develop buds and to separate mother and daughter cells. In contrast, cells of the Δvtc4 strains grew as septate filaments, with the percentage of filamentous cells increasing at higher phosphate concentrations (Table 1). In 1 mM KH2PO4, the majority of Δvtc4 cells grew as budding yeast-like cells whereas cells were elongated and contained some septa at 7.35 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 2B). In 250 mM KH2PO4, the majority of Δvtc4 cells appeared as branched, septate hyphae (Fig. 2B).

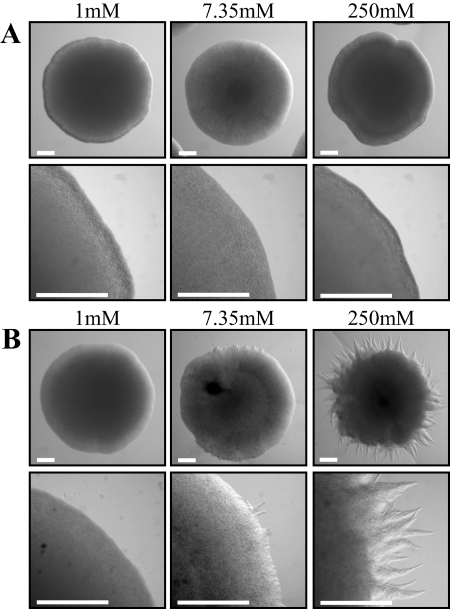

FIG. 1.

Strains with the Δvtc4 allele exhibit a filamentous colonial morphology. Wild-type (A) and Δvtc4 (B) strains were grown for 5 days at 30°C on MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7). Colonies are shown at ×2 and ×6 magnifications. (A) Wild-type colonies exhibit a smooth, uniform colonial morphology. (B) Colonies of Δvtc4 mutant strains have a filamentous morphology in high concentrations of KH2PO4. Scale bars = 1 mm.

FIG. 2.

The Δvtc4 mutants have a filamentous cellular morphology in a high phosphate concentration. Wild-type (A) or Δvtc4 (B) cells were grown in MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7). (A) Wild-type haploid U. maydis cells grow as budding yeast regardless of the extracellular phosphate concentration. (B) Δvtc4 cells grow predominately as budding yeast cells in 1 mM KH2PO4. In contrast, the majority of Δvtc4 cells grown in 7.35 mM KH2PO4 appear as elongated cells. At high phosphate concentrations (250 mM), the Δvtc4 strains grow predominately as septate, branched hyphal filaments. Images were captured by DIC or epifluorescence microscopy to observe CAL-stained cell walls. Scale bars = 20 μm.

TABLE 1.

Correlation between increased budding and phosphate concentration

| Straina and KH2PO4 concn (mM) | % Unbudded cells | % Budding cells (1 bud) | % Multibudded cells (>2 buds) | % Filamentous cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | ||||

| 1 | 83 ± 9.3b | 17 ± 9.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.41 |

| 7.35 | 76 ± 12 | 24 ± 12 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 250 | 65 ± 5.0 | 35 ± 5.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Δvtc4 | ||||

| 1 | 75 ± 7.8 | 7.8 ± 4.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 17 ± 9.4 |

| 7.35 | 64 ± 8.9 | 8.0 ± 2.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 28 ± 8.4 |

| 250 | 48 ± 10 | 15 ± 4.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 37 ± 13 |

| Δubc1 | ||||

| 1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 99 ± 1.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 7.35 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 99 ± 0.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 250 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 97 ± 3.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Δvtc4 ubc1 | ||||

| 1 | 73 ± 9.2 | 7.0 ± 2.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 21 ± 6.4 |

| 7.35 | 70 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 26 ± 1.4 |

| 250 | 40 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 54 ± 0.0 |

Wild-type, Δvtc4, Δubc1, or Δvtc4 ubc1 cells were grown at 30°C in minimal medium plus 1% glucose and either 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7) for 18 h.

The values shown are means and standard deviations.

The vtc4 gene is required for polyP accumulation in the vacuole.

Cells of S. cerevisiae rapidly accumulate large amounts of polyP in the vacuole when switched from a low-phosphate to a high-phosphate medium, and the S. cerevisiae vtc4 mutant exhibits a decrease in the amount of polyP stored in the vacuole (26). To observe polyP accumulation in the vacuole of wild-type and Δvtc4 strains of U. maydis, cells were stained with Toluidine Blue O and observed microscopically (see Materials and Methods). In wild-type cells, no vacuolar accumulation of polyP was observed in budding yeast cells grown in 1 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 3A). However, wild-type budding cells grown in 7.35 or 250 mM KH2PO4 showed large vacuolar accumulations of stained polyP (Fig. 3A). Similar to wild-type cells, budding yeast cells of the Δvtc4 strains showed no vacuolar accumulation of polyP when grown in 1 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 3B). However, in stark contrast to wild-type cells, budding or filamentous cells of the Δvtc4 strains grown in 7.35 or 250 mM KH2PO4 showed no vacuolar accumulation of polyP (Fig. 3B). This suggests that vtc4 is essential for the accumulation of polyP in the vacuole under conditions of high extracellular phosphate.

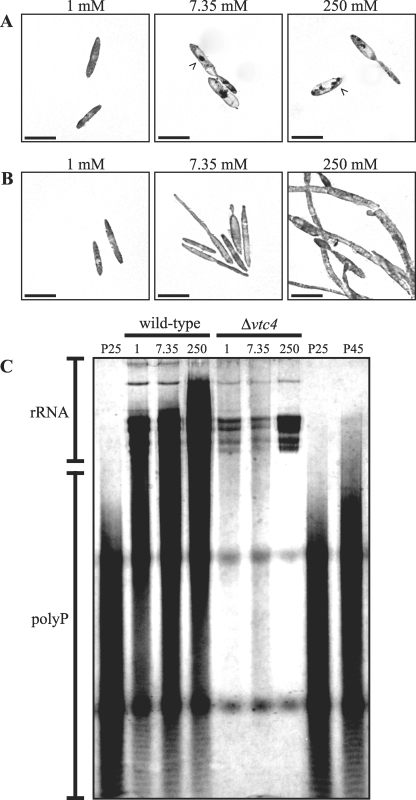

FIG. 3.

The Δvtc4 strains lack accumulated vacuolar polyP at high concentrations of extracellular phosphate. Wild-type (A) or Δvtc4 (B) cells were grown in MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7). Cells were stained with Toluidine Blue O to observe polyP. (A) Wild-type cells grown in 1 mM KH2PO4 do not show polyP accumulated in the vacuole. In contrast, wild-type cells grown in either 7.35 or 250 mM KH2PO4 show large accumulations of polyP in the vacuole. polyP accumulations are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Similar to wild-type cells, Δvtc4 cells grown in 1 mM KH2PO4 grow as budding cells which lack polyP accumulation in the vacuole. In contrast to wild-type cells, Δvtc4 cells grown in 7.35 mM KH2PO4 produce elongated cells which lack polyP accumulated in the vacuole. Likewise, in 250 mM KH2PO4, Δvtc4 cells exhibit a filamentous morphology and lack vacuole polyP accumulation. Images were captured by DIC microscopy. Scale bars = 20 μm. (C) polyP accumulation in wild-type and Δvtc4 cells after overnight growth in MM plus 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4. A 20% polyacrylamide gel was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA of each sample and 20 μg of polyP ladder (P25 or P45 for the major polyP chain length). polyP was stained with Toluidine Blue O. The increasing amounts of polyP in wild-type extracts correlate with increasing concentrations of KH2PO4. In contrast, only a slight accumulation of polyP is visible in extracts from Δvtc4 cells grown in 1 mM or 7.35 mM KH2PO4 and no accumulation of polyP is visible in extracts from the Δvtc4 mutant grown in 250 mM KH2PO4.

To further investigate the reduction of polyP in Δvtc4 mutants, polyP was isolated from wild-type and Δvtc4 cells after growth overnight in MM plus 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 and examined on a polyacrylamide gel after staining for polyP (see Materials and Methods) (26). The amount of polyP extracted from wild-type cells increased at higher KH2PO4 concentrations, with the greatest accumulation of polyP present in cells grown in 250 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 3C). In contrast, only a slight accumulation of polyP was observed in samples extracted from Δvtc4 cells grown in 1 or 7.35 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 3C). The Δvtc4 cells grown in 250 mM KH2PO4 produced no detectable polyP (Fig. 3C). To investigate whether this defect in polyP accumulation was only apparent during active growth, wild-type and Δvtc4 cells were grown to stationary phase (3.5 days) and polyP was examined. The Δvtc4 mutant also showed a failure to accumulate polyP under these conditions (data not shown). We should note that no differences were observed between wild-type and Δvtc4 strains of the two different mating types (data not shown).

It was previously shown that the Δubc1 mutant had defects in polyP accumulation in the vacuole (22). However, unlike the Δvtc4 mutant, this defect was variable, with multibudded cells showing some cells with vacuolar polyP and others lacking polyP (22). To further investigate differences in polyP accumulation in this mutant, polyP was extracted from Δubc1 mutants after growth overnight in MM plus 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 and examined on a polyacrylamide gel (see Materials and Methods) (26). Unlike the Δvtc4 mutant, the Δubc1 mutant only showed a reduction of polyP accumulation during growth in MM with 7.35 KH2PO4 (data not shown). In addition, the reduction in polyP accumulation was no longer apparent when the mutant reached stationary phase after 3.5 days (data not shown). Therefore, the Δubc1 mutant appears to have a delay in polyP accumulation.

Mating is unaffected in Δvtc4 strains.

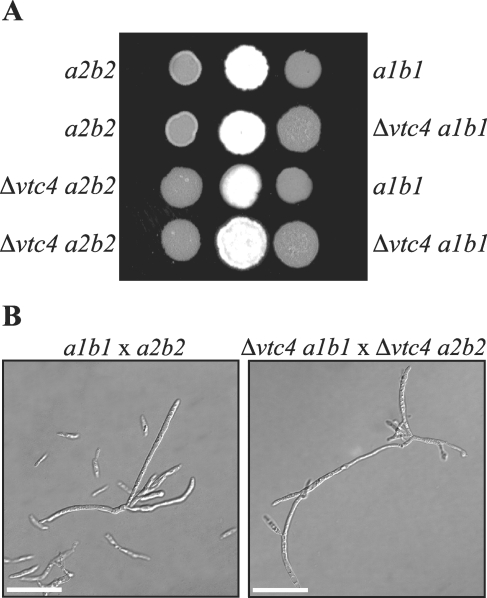

During infection, haploid U. maydis cells of opposite mating types extend conjugation tubes that fuse to form a dikaryon that colonizes plant tissue. Mating and filamentation are therefore essential factors for U. maydis pathogenesis. To determine whether vtc4 is required during mating, strains of opposite mating types were combined on charcoal plates and evaluated for successful mating (indicated by filamentous growth). We found that deletion of vtc4 had no effect on the ability of the mutant cells to mate when tested with compatible, wild-type mating partners (521 [a1b1] or 518 [a2b2]) (Fig. 4A). Also, no defect was observed when vtc4 deletion strains of opposite mating types were combined on mating medium (Fig. 4A). Filaments were also scraped off mating plates and observed microscopically. By this method, wild-type cells are observed in a number of cellular morphologies, i.e., yeast-like cells, yeast-like cells extending conjugation tubes, and hyphal filaments (Fig. 4B). Similar to wild-type cells, Δvtc4 cells were observed as yeast-like cells, yeast-like cells with conjugation tubes, and hyphal filaments (Fig. 4B). We concluded that deletion of vtc4 does not increase or decrease mating filament formation under the conditions used in a standard mating assay.

FIG. 4.

Mating is unaffected in Δvtc4 strains. (A) To assess mating capability, cultures of wild-type or Δvtc4 cells were cospotted onto CM-plus-charcoal plates and incubated for 2 days at 30°C. Drops of single wild-type and mutant strains were included as controls. A positive mating reaction is indicated by a fuzzy colony morphology. Combinations of mutant strains show that deletion of vtc4 does not reduce the ability to mate. (B) To examine mating filaments, cells were scraped from CM-plus-charcoal plates and resuspended in sdH2O. Wild-type cells responding to pheromone extend conjugation tubes that fuse to form a filamentous dikaryon. The Δvtc4 strains also extend conjugation tubes that fuse to form mating filaments. Images were captured by DIC microscopy. Scale bars = 20 μm.

The Δvtc4 mutants have reduced virulence in maize seedlings.

Plants infected with U. maydis generally produce anthocyanin pigment on leaves and stems and form large tumors filled with proliferating fungal cells. Within the plant tumors, fungal cells differentiate into melanized, echinulated teliospores which eventually emerge from ruptured plant tissue and germinate to reinitiate the life cycle. Given the positive mating ability of the Δvtc4 mutants, we expected the cells to cause disease on maize seedlings. We therefore inoculated 1-week-old plants by stem injection with mixtures of wild-type strains, of wild-type and mutant strains, or of mating-compatible mutants. Plants were scored for disease after 2 weeks, and a disease index was calculated (Table 2). Contrary to expectation, the disease index was reduced in plants infected with a mixture of Δvtc4 mutants of opposite mating types, compared with the mixture of wild-type strains. Specifically, the infections with the mutants yielded a reduced number of dead plants and an increase in the number of plants with no symptoms (Table 2). The mutants could clearly cause the full range of disease symptoms, but it was striking that far fewer plants were killed in these infections. The reduction in plant death could indicate a defect in early events of penetration and establishment of infection such that less severe symptoms developed. It is also possible that a less aggressive infection by the mutants might allow more time for host defenses to act to maintain the viability of the plant. The disease indices were also reduced when plants were infected with a mixture of a Δvtc4 mutant with a wild-type strain of the opposite mating type, perhaps indicating haploinsufficiency (Table 2). Given that the formation of mating filaments appeared to be unaffected by the Δvtc4 mutation (Fig. 4), we favor the possibility that the mutants have a specific defect during the early stages of growth in planta. That is, the ability to utilize vacuolar polyP as a phosphate source may be crucial during the initial stages of infection, when the available phosphate level may be low.

TABLE 2.

Disease ratingsa

| Cross | No. of plants with following disease index:

|

No. of plants | Avg disease index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 518 × 521 | 0 | 23 | 18 | 6 | 10 | 92 | 149 | 3.9 |

| 518 × Δvtc4 a1b1 | 9 | 37 | 29 | 14 | 8 | 28 | 125 | 2.5 |

| Δvtc4 a2b2 × 521 | 22 | 22 | 28 | 10 | 12 | 27 | 121 | 2.4 |

| Δvtc4 a2b2 × Δvtc4 a1b1 | 24 | 37 | 46 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 139 | 1.8 |

Disease ratings are as follows: 0, no disease; 1, anthrocyanin production; 2, leaf tumors; 3, small stem tumors; 4, large stem tumors; 5, death. Infection assays were performed on three separate occasions with similar outcomes, and the results were pooled.

Plants infected with Δvtc4 strains show reduced accumulation of fungal cells.

To further investigate the defect in virulence in Δvtc4 strains, epidermal peeling was performed on leaves infected with mating cultures of wild-type strains or Δvtc4 strains of opposite mating types (see Materials and Methods). After 6 days, leaves infected with a wild-type cross contained a mixture of yeast cells, short hyphal cells, and regions completely colonized by proliferating fungal hyphae (data not shown). When leaves of plants infected with the Δvtc4 strains were observed, it was immediately apparent that fewer Δvtc4 cells were present in the inoculated plants. In addition, no Δvtc4 hyphae were observed in the leaf samples analyzed after 6 days (data not shown). U. maydis cells could not be observed at later time points because of an increase in leaf pigmentation. However, the inoculated plants developed mild symptoms (after 2 weeks) indicating that the mutant cells present at day 6 eventually form some hyphae.

Differentiation into teliospores is unaffected in Δvtc4 strains.

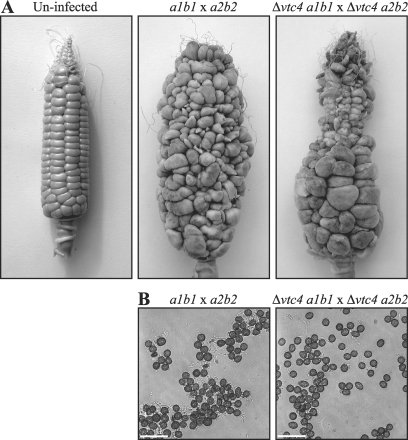

Dikaryotic hyphae of U. maydis differentiate into melanized teliospores within tumors, and these eventually rupture to disperse spores. To investigate whether vtc4 is required for teliospore production, 2-month-old maize plants were inoculated by injection of mating cultures into the silk channels of developing ears. Maize plants were inoculated with crosses of wild-type strains 518 (a2b2) and 521 (a1b1) or with a mixture of Δvtc4 a2b2 and Δvtc4 a1b1 mutants. The formation of teliospores was assessed at 3 weeks after inoculation, and we found that infections with both wild-type and Δvtc4 strains resulted in tumors filled with black teliospores. Differences in teliospore morphology, maturity, or abundance were not evident in this assay (Fig. 5 and unpublished observations). That is, tumor sections from plants infected with either wild-type or Δvtc4 mating cultures contained masses of mature teliospores that displayed the echinulated spore surface. Furthermore, teliospores isolated from plants infected with a Δvtc4 mating culture showed no differences in germination compared to wild-type spores (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Teliospore production is unaffected in Δvtc4 strains. (A) The developing ears of 2-month-old maize plants were inoculated with crosses of wild-type strains 518 (a2b2) and 521 (a1b1) or with a mixture of Δvtc4 a2b2 and Δvtc4 a1b1 strains. The kernels of ears infected with wild-type U. maydis develop into large tumors that are filled with fungal cells differentiating into melanized teliospores (resulting in the tumors' black appearance). Likewise, ears infected with a Δvtc4 a2b2-Δvtc4 a1b1 cross also produced large tumors filled with melanized teliospores. The levels of teliospore production were similar in ears infected with mixtures of wild-type or mutant strains. (B) Teliospores isolated from tumors of plants infected with crosses of wild-type strains 518 (a2b2) and 521 (a1b1) or with a mixture of the Δvtc4 a2b2 and Δvtc4 a1b1 strains. The morphology of teliospores isolated from plants infected with the mutants was indistinguishable from that of teliospores from a wild-type infection. Images were captured by DIC microscopy. Scale bars = 20 μm.

It is possible that the differences in virulence observed between the seedling infection assay and the infection of developing ears may be attributed to the length of time required for U. maydis cells to reach meristematic tissue. In the seedling assay, fungal cells must penetrate the plant surface to colonize meristematic tissue, whereas in the developing-ear assay, fungal cells are directly inoculated via the silk channels into the meristematic tissue of the developing embryo. It is also possible that the differences may be attributed to differences in phosphate availability. In plants, the majority of phosphate is stored in actively growing tissues, whereas the xylem and older leaves contain relatively low levels of phosphate (1 to 7 mM) (29). In tissues with lower levels of available phosphate, the ability to utilize vacuolar polyP as a phosphate source may be crucial during the initial stages of infection.

Deletion of vtc4 suppresses the multibudded phenotype of Δubc1 mutants and reduces budding in exogenous cAMP.

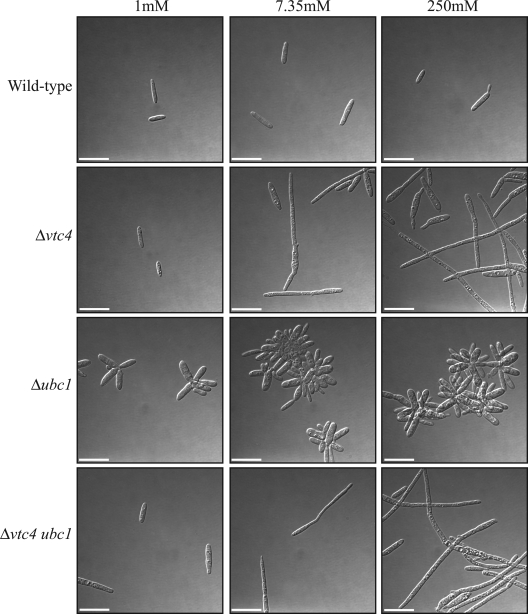

To further investigate the connection between the PKA pathway and intracellular phosphate storage, double mutants with the genotype Δvtc4 ubc1 were generated and phenotypically analyzed (see Materials and Methods). Specifically, we inoculated 1 × 106 cells into MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7) and grew the cultures overnight. As described previously, wild-type cells grew as budding yeast cells regardless of the phosphate concentration, with the percentage of budding cells increasing at higher phosphate concentrations (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The Δubc1 mutant exhibited a multibudded cellular phenotype at all phosphate concentrations (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Also as described previously, the Δvtc4 mutant grew as filaments in this medium, with the number of filaments increasing at higher phosphate concentrations (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The Δvtc4 ubc1 double mutants exhibited a phenotype identical to that of the Δvtc4 single mutants (Fig. 6). That is, the Δvtc4 ubc1 strains grew predominately as budding yeast cells with a small number of filaments in 1 mM KH2PO4 (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The Δvtc4 ubc1 mutant cells in medium with 7.35 mM KH2PO4 showed an elongated cellular morphology and a higher percentage of filamentous cells (Fig. 6 and Table 1). In 250 mM KH2PO4, Δvtc4 ubc1 strains grew predominately as filaments, and this result indicated that mutation of vtc4 completely suppressed the multibudded phenotype of the Δubc1 mutant (Fig. 6 and Table 1). In these double mutants, there was no evidence of the multibudding phenotype typical of ubc1 mutants.

FIG. 6.

Deletion of vtc4 suppresses the multibudded phenotype of a ubc1 mutant. Wild-type, Δvtc4, Δubc1, or Δvtc4 ubc1 cells were grown in MM plus 1% glucose and 1, 7.35, or 250 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7). Wild-type U. maydis grows as budding yeast regardless of the extracellular phosphate concentration. The Δvtc4 mutants grow as budding yeast in 1 mM KH2PO4, as elongated cells in 7.35 mM, and as hyphal filaments in 250 mM KH2PO4. The Δubc1 mutant exhibits a multibudded phenotype, regardless of the extracellular phosphate concentration. The Δvtc4 ubc1 double mutants have the same cellular morphology as the Δvtc4 single mutants. In 1 mM KH2PO4, Δvtc4 ubc1 mutant cells grow predominately as budding yeast cells. The Δvtc4 ubc1 cells grown in 7.35 mM KH2PO4 have an elongated cellular morphology, and cells grown in 250 mM KH2PO4 exhibit a hyphal morphology. Images were captured by DIC microscopy. Scale bars = 20 μm.

The ability of the Δvtc4 mutation to suppress the multibudded phenotype of wild-type cells grown in exogenous cAMP was also tested. We have shown previously (11) that these cells are multibudded, with the percentage of multibudded cells increasing at higher cAMP concentrations (Table 3). We found that Δvtc4 cells also became multibudded in medium with exogenous cAMP, but this phenotype was greatly reduced compared to wild-type cells (Table 3). Similar to the wild type, there was nonpolar budding in a number of the Δvtc4 cells. We conclude that vtc4 is required during cAMP/PKA-induced budding in U. maydis.

TABLE 3.

Relationship between multiple budding and cAMP concentration

| Straina and cAMP concn (mM) | % Unbudded cells | % Budding cells (1 bud) | % Multibudded cells (>2 buds) | % Filamentous cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ||||

| 0 | 73 ± 0.0b | 26 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 1 | 77 ± 6.4 | 21 ± 3.5 | 3.0 ± 2.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 5 | 27 ± 2.1 | 60 ± 6.4 | 14 ± 8.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 10 | 20 ± 11 | 28 ± 2.1 | 53 ± 9.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Δvtc4 | ||||

| 0 | 68 ± 14 | 15 ± 8.5 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 16.6 ± 23 |

| 1 | 78 ± 0.7 | 18 ± 7.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.5 ± 6.4 |

| 5 | 60 ± 0.7 | 33 ± 2.8 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 10 | 36 ± 4.9 | 40 ± 5.7 | 24 ± 11 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

Wild-type and Δvtc4 cells were grown at 30°C in minimal medium plus 1% glucose and either 0, 1, 5, or 10 mM cAMP for 18 h.

The values shown are means and standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The U. maydis vtc4 homolog is required for polyP accumulation in the vacuole.

Pi is an essential nutrient required for many structural and metabolic functions in cells. Levels of intracellular phosphate are therefore tightly regulated, and excess phosphate is stored in the vacuole as polymers of polyP to be utilized in times of phosphate limitation. polyP also has other functions, including sequestration and storage of cations, phosphate transport, cell envelope formation, control of gene expression, regulation of enzyme activities, adaptation to stress, and serving as an alternative energy source (reviewed in reference 21). The vtc4 mutant of S. cerevisiae shows a reduced capacity to accumulate polyP in the vacuole, and this reduction is proposed to be due to a lack of vacuole fusion (26). In general, the Vtc1p, Vtc2p, Vtc3p, and Vtc4p complex in yeast is required for the initial steps of vacuole fusion and Pi is thought to be transported to the vacuole via fusion-dependent endocytosis (25, 26). Similar to S. cerevisiae, we found that U. maydis Δvtc4 mutants have a dramatic reduction in the amount of polyP stored in the vacuole. In addition, polyP extractions showed only minimal accumulation of polyP in Δvtc4 cells grown in 1 or 7.35 mM KH2PO4 and no visible polyP for Δvtc4 cells grown in 250 mM KH2PO4. The small amounts of polyP extracted from cells grown in 1 or 7.35 mM KH2PO4 might be attributed to phosphate storage in other compartments of the cell that are known to play a minor role, such as the nucleus, mitochondrion, or cell envelope (21). It has been suggested that synthesis of polyP controls intracellular phosphate homeostasis and influences the expression of PHO genes, including those encoding transport functions (27). Therefore, the lack of polyP in the vtc4 mutant in 250 mM KH2PO4 might reflect down regulation of PHO gene expression and transport functions in response to a high phosphate level in combination with a defect in storage caused by loss of Vtc4 function. In contrast to the Δvtc4 mutants, the Δubc1 mutant showed a reduction in polyP accumulation only during growth in MM plus 7.35 KH2PO4 and this reduction was no longer apparent by the time the mutant had reached stationary phase. Therefore, the Δubc1 mutant was only delayed in polyP accumulation and this could explain why previous observations revealed that only a proportion of Δubc1 cells lacked polyP in the vacuole (22). PKA regulates the expression of a number of genes involved in phosphate uptake, sensing and storage, and the delay in polyP accumulation could therefore be a result of defective sensing of the phosphate status of the cell or defective signaling (22). Overall, these observations indicate that Vtc4 in U. maydis shares polyP-related functions with Vtc4p in yeast and reveal a conserved connection between cAMP signaling and phosphate accumulation.

Vtc4 regulates cellular morphology in U. maydis.

A key finding of this study was that Δvtc4 mutants grow as filaments in high-phosphate medium, thus providing a direct link between intracellular phosphate levels and morphogenesis in U. maydis. The role of Vtc4 in the regulation of filamentation is intriguing because intracellular phosphate levels are a reflection of the external environment and the protein may therefore contribute to the ability of U. maydis to sense the host environment. An important aspect of this sensing process is that the fungus must switch to a filamentous morphology to facilitate invasion and proliferation. The cytosolic concentration of phosphate in maize cells is maintained at approximately 5 to 10 mM (29). Clues to the mechanism by which Vtc4 could regulate cellular morphology come from additional studies with yeast. In a large-scale study of protein-protein interactions in S. cerevisiae, Vtc4p was shown to physically interact with Bzz1p (16). Bzz1p is a member of a protein complex that marks sites of cortical actin polymerization during polarized growth. This complex includes the WASP protein Las17p, the actin-interacting protein Vrp1p, and the myosins Myo3p and Myo5p (32). Bzz1p has also been shown to be involved in endocytosis of vesicles to the vacuole (33). We speculate that if a similar interaction occurs in U. maydis, Vtc4 could participate in a protein complex with links to polarized growth and, in this case, negatively regulate filamentation.

The filamentous morphology of the Δvtc4 mutants also suggests that Vtc4 might influence signaling through the PKA pathway to regulate the morphological transition from budding yeast to the filamentous dikaryon. Vtc4 contains an SPX domain that is present in proteins that both sense phosphate levels and are involved in G-protein-associated signal transduction. In S. cerevisiae, the N terminus of the SPX protein Syg1p directly binds to the G-protein β subunit to ultimately inhibit transduction of the mating pheromone signal (34). Interestingly, there is no clear SYG1 homolog in the U. maydis genome (K.J.B., unpublished observations). Of the four SPX proteins encoded by the genome, one shows only weak homology to Syg1 (gene Um04146; 29% identity and related to phosphate transporter 1) and to Xpr1 proteins in higher eukaryotes (∼30% identity), one is Vtc4, and two are predicted to encode the phosphate transporters similar to Pho81p and Pho91p (Um02860 and Um04759). In U. maydis, the mating pheromone signal is transduced via the PKA signaling pathway and a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (17). It is possible that Vtc4 in U. maydis performs the roles of both yeast proteins Syg1p and Vtc4p by negatively signaling to the PKA pathway to regulate mating and morphology (Syg1p) and by sensing phosphate levels to regulate polyP stores in the vacuole (Vtc4p).

Connections between phosphate and PKA signaling.

Previously, SAGE analysis revealed that transcripts for a number of genes connected with phosphate metabolism were elevated in a Δubc1 (high PKA activity) library and/or reduced in a Δadr1 (low PKA activity) library (22). Several of these genes were orthologs of components of the PHO regulatory pathway that is involved in the acquisition of Pi in S. cerevisiae (Pho84p, acid phosphatase, Vtc1p, and Vtc4p). A connection between phosphate signaling and PKA signaling has also been found in S. cerevisiae (10). That is, addition of phosphate to phosphate-starved cells of S. cerevisiae affects targets of the PKA pathway and deletion of phosphate permeases affected both phosphate uptake and PKA signaling (10). To further investigate the connection between phosphate acquisition and storage and PKA signaling in U. maydis, double Δvtc4 ubc1 mutants were generated and phenotypically analyzed. We found that deletion of vtc4 completely suppressed the multibudded phenotype of the ubc1 mutant and budding was also reduced in the Δvtc4 mutant grown in exogenous cAMP. These results support the hypothesis that Vtc4-dependent polyP stores are crucial for PKA-induced budding. It is possible that polyP stores in the vacuole act both as a sink for phosphate and as an alternative energy source (ATP substitute), as has been proposed for other microorganisms (19). This hypothesis is supported by the SAGE data that show that the expression of vtc4 increases in the Δubc1 mutant (expected to have high PKA activity) during budding (22). As mentioned above, it is also possible that the function of Vtc4 is to negatively regulate filamentation via interaction with the PKA pathway and that this may occur independently of phosphate storage.

Vtc4 is required for symptom development in maize.

Maize seedlings infected with Δvtc4 mutants showed reduced symptom development, and this virulence defect could result from an inability of the fungus to store polyP in the vacuole. One of the proposed roles of vacuolar polyP is to act as a reservoir of Pi to be utilized by the cell under environmental conditions where the extracellular phosphate level is low (21). After nitrogen, phosphate is the second most limiting macronutrient for plant growth (29). The cytosolic concentration of phosphate in maize cells is maintained at approximately 5 to 10 mM, a concentration at which U. maydis grows well (29). However, it is not clear that the fungus can access this phosphate and the amount available in the intercellular spaces where the fungus is often found may be limiting. Therefore, it is possible that U. maydis must rely on stored intracellular phosphate to provide enough phosphate for structural and metabolic needs, at least during the initial phase of growth in the plant. Of course, there are other possibilities for the reduction in the number of Δvtc4 cells in planta. For example, there could be decreased polyP in the cell envelope that might have structural implications for filamentous growth or interaction with host cells. This idea is supported by observations of pathogenic bacteria such as Neisseria meningitidis, where >50% of the polyP synthesized in the cell is localized to the cell exterior. This extracellular polyP has been proposed to function as a protective, capsule-like coating (19, 35). It is possible that deletion of vtc4 in U. maydis might influence polyP accumulation on the cell exterior by disrupting phosphate homeostasis in the cell. In turn, a change in the fungal cell surface might influence both morphogenesis and the interaction of the fungus with the plant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council to J.K. J.K. is a Burroughs Welcome Fund Scholar in Molecular Pathogenic Mycology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, D. L., J. D. Egan, M. E. Mayorga, and S. E. Gold. 2000. The Ustilago maydis ubc4 and ubc5 genes encode members of a MAP kinase cascade required for filamentous growth. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:781-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banuett, F., and I. Herskowitz. 1994. Identification of fuz7, a Ustilago maydis MEK/MAPKK homolog required for a-locus-dependent and -independent steps in the fungal life cycle. Genes Dev. 8:1367-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banuett, F., and I. Herskowitz. 1996. Discrete developmental stages during teliospore formation in the corn smut fungus, Ustilago maydis. Development 122:2965-2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett, K. J., S. E. Gold, and J. W. Kronstad. 1993. Identification and complementation of a mutation to constitutive filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:274-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolker, M., S. Genin, C. Lehmler, and R. Kahmann. 1995. Genetic regulation of mating and dimorphism in Ustilago maydis. Can. J. Bot. 73:320-325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolker, M., M. Urban, and R. Kahmann. 1992. The a mating type locus of U. maydis specifies cell signaling components. Cell 68:441-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen, J. J. 1963. Corn smut induced by Ustilago maydis. Am. Phytopathol. Soc. Monogr. 2:1-41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson, R. C., J. R. Blankenship, P. R. Kraus, M. DeJesus Berrios, C. M. Hull, C. D'Souza, P. Wang, and J. Heitman. 2002. A PCR-based strategy to generate integrative targeting alleles with large regions of homology. Microbiology 148:2607-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durrenberger, F., K. Wong, and J. W. Kronstad. 1998. Identification of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit required for virulence and morphogenesis in Ustilago maydis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5684-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giots, F., M. C. V. Donaton, and J. M. Thevelein. 2003. Inorganic phosphate is sensed by specific phosphate carriers and acts in concert with glucose as a nutrient signal for activation of the protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1163-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold, S., G. Duncan, K. Barrett, and J. W. Kronstad. 1994. cAMP regulates morphogenesis in the fungal pathogen Ustilago maydis. Genes Dev. 8:2805-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold, S. E., S. M. Brogdon, M. E. Mayorga, and J. W. Kronstad. 1997. The Ustilago maydis regulatory subunit of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase is required for gall formation in maize. Plant Cell 9:1585-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartmann, H. A., R. Kahmann, and M. Bolker. 1996. The pheromone response factor coordinates filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 15:1632-1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holliday, R. 1961. The genetics of Ustilago maydis. Genet. Res. Cambridge Soc. 2:204-230. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holliday, R. 1974. Ustilago maydis, p. 575-595. In R. C. King (ed.), Handbook of genetics, vol. 1. Plenum, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori, and Y. Sakaki. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahmann, R., T. Romeis, M. Bolker, and J. Kamper. 1995. Control of mating and development in Ustilago maydis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5:559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klose, J., M. Moniz de Sa, and J. W. Kronstad. 2004. Lipid-induced filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 52:823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornberg, A., N. N. Rao, and D. Ault-Riche. 1999. Inorganic polyphosphate: a molecule of many functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:89-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kronstad, J. W., and C. Staben. 1997. Mating type in filamentous fungi. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31:245-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulaev, I., and T. Kulakovskaya. 2000. Polyphosphate and phosphate pump. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:709-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larraya, L. M., K. J. Boyce, A. So, B. Steen, S. Jones, M. Marra, and J. W. Kronstad. 2005. Serial analysis of gene expression reveals conserved links between protein kinase A, ribosome biogenesis and phosphate metabolism in Ustilago maydis. Eukaryot. Cell 4:2029-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Espinoza, A. D., J. Ruiz-Herrera, C. G. Leon-Ramirez, and S. E. Gold. 2004. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling pathways modulate the pH-induced yeast-to-mycelium dimorphic transition in the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Curr. Microbiol. 49:274-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayorga, M. E., and S. E. Gold. 1999. A MAP kinase encoded by the ubc3 gene of Ustilago maydis is required for filamentous growth and full virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 34:485-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller, O., M. J. Bayer, C. Peters, J. S. Andersen, M. Mann, and A. Mayer. 2002. The Vtc proteins in vacuole fusion: coupling NSF activity to V0 trans-complex formation. EMBO J. 21:259-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa, N., J. DeRisi, and P. O. Brown. 2000. New components of a system for phosphate accumulation and polyphosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by genomic expression analysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:4309-4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson, B. L., J. O. Lagerstedt, J. R. Pratt, J. Pattison-Granberg, K. Lundh, S. Shokrollahzadeh, and F. Lundh. 2003. Regulation of phosphate acquisition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 43:225-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Schachtman, D. P., R. J. Reid, and S. M. Ayling. 1998. Phosphorus uptake by plants: from soil to cell. Plant Physiol. 116:447-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snetselaar, K. M., and C. W. Mims. 1992. Sporidial fusion and infection of maize seedlings by the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Mycologia 84:193-203. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snetselaar, K. M., and C. W. Mims. 1994. Light and electron microscopy of Ustilago maydis hyphae in maize. Mycol. Res. 98:347-365. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soulard, A., T. Lechler, V. Spiridonov, A. Shevchenko, A. Shevchenko, Li, R., and B. Winsor. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Bzz1p is implicated with type I myosins in actin patch polarization and is able to recruit actin-polymerizing machinery in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7889-7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soulard, A., S. Friant, C. Fitterer, C. Orange, G. Kaneva, G. Mirey, and B. Winsor. 2005. The WASP/Las17p-interacting protein Bzz1p functions with Myo5p in an early stage of endocytosis. Protoplasma 226:89-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spain, B. H., D. Koo, M. Ramakrishnan, B. Dzudzor, and J. Colicelli. 1995. Truncated forms of a novel yeast protein suppress the lethality of a G protein alpha subunit deficiency by interacting with the beta subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25435-25444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinsley, C. R., and E. C. Gotschlich. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the meningococcal polyphosphate kinase gene: production of polyphosphate synthesis mutants. Infect. Immun. 63:1624-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]