Abstract

Exposure of Escherichia coli strains deficient in molybdopterin biosynthesis (moa) to the purine base N-6-hydroxylaminopurine (HAP) is mutagenic and toxic. We show that moa mutants exposed to HAP also exhibit elevated mutagenesis, a hyperrecombination phenotype, and increased SOS induction. The E. coli rdgB gene encodes a protein homologous to a deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphatase from Methanococcus jannaschii that shows a preference for purine base analogs. moa rdgB mutants are extremely sensitive to killing by HAP and exhibit increased mutagenesis, recombination, and SOS induction upon HAP exposure. Disruption of the endonuclease V gene, nfi, rescues the HAP sensitivity displayed by moa and moa rdgB mutants and reduces the level of recombination and SOS induction, but it increases the level of mutagenesis. Our results suggest that endonuclease V incision of DNA containing HAP leads to increased recombination and SOS induction and even cell death. Double-strand break repair mutants display an increase in HAP sensitivity, which can be reversed by an nfi mutation. This suggests that cell killing may result from an increase in double-strand breaks generated when replication forks encounter endonuclease V-nicked DNA. We propose a pathway for the removal of HAP from purine pools, from deoxynucleotide triphosphate pools, and from DNA, and we suggest a general model for excluding purine base analogs from DNA. The system for HAP removal consists of a molybdoenzyme, thought to detoxify HAP, a deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphatase that removes noncanonical deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates from replication precursor pools, and an endonuclease that initiates the removal of HAP from DNA.

Extensive investigation has shown that purine base analogs can be mutagenic to cells. 2-Aminopurine has been shown to promote base-pair transitions in Escherichia coli and is highly mutagenic (47). It has been shown that the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I inserts either deoxythymidine triphosphate or deoxycytosine triphosphate opposite N-6-hydroxylaminopurine (HAP) in an oligonucleotide template and that HAP induces both A:T to G:C and G:C to A:T transition mutations in E. coli at a similar frequency (44). Both xanthine and hypoxanthine are readily taken up by cells and are quickly converted to their corresponding nucleotides during purine salvage. Furthermore, hypoxanthine, IMP, and XMP can arise endogenously from purine interconversion and from the deamination of canonical bases (51, 52, 62). Inosine residues in DNA have been shown to result in transition mutations, and xanthosine residues in DNA are assumed to result in transition mutations as well (22). Therefore, it is important for an organism to possess enzymes that protect it from exogenous and endogenous purine base analogs.

Schaaper and colleagues have shown that E. coli strains deficient in molybdopterin biosynthesis are hypersensitive to HAP for both mutagenesis and toxicity (29). They established that HAP sensitivity is conferred by the inactivation of one of several genes (mol genes) involved in the biosynthesis and activation of the molybdenum cofactor, molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide (MGD). Two mol genes that we will discuss in this report are moa and moeA. MGD is required for functional E. coli molybdoenzymes, which have been shown to perform aerobic and anaerobic redox reactions (21, 46). Unfortunately, to date no strain defective in one of the known molybdoenzymes has displayed HAP sensitivity. Therefore, it has been concluded that HAP sensitivity in E. coli mol mutants is due to the absence of an active MGD and that an unidentified molybdoenzyme is involved in detoxifying HAP (29).

Our laboratory has shown that an E. coli recA200(Ts) rdgB double mutant is inviable at the nonpermissive temperature and that overexpression of the wild-type purA gene rescues viability of this strain at 42°C (6, 7). The RecA protein plays a central role in homologous recombination and, in conjunction with the LexA protein, induces the SOS regulon in response to DNA damage (14, 36, 45). The RdgB protein, along with the human and Methanococcus jannaschii homologs, have been shown to have deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphatase activity on several purine base analog nucleotide triphosphates (4, 34). Additionally, Clyman and Cunningham have shown that an rdgB mutant displays a hyperrecombinogenic phenotype and shows elevated levels of SOS expression. They suggested that in the absence of RdgB a lesion develops in DNA that requires repair by a RecA-mediated event (6). The purA gene encodes adenylosuccinate synthetase that, along with the purB gene product, catalyzes the conversion of IMP into AMP (62). The facts that overexpression of purA rescues the synthetic lethal phenotype of a recA200(Ts) rdgB double mutant and that RdgB has activity against purine base analog nucleoside triphosphates suggest that the lesions in recA200(Ts) rdgB strains develop from the incorporation of purine base analogs into polymerizing DNA.

Endonuclease V has been shown to recognize a wide variety of DNA lesions, including mismatched base pairs and inosine and xanthosine residues in DNA (20, 59-61). Endonuclease V (nfi) mutants have been shown to result in an increase of transition mutations in the presence of nitrous acid (57). These results suggest that endonuclease V helps protect cells against the mutagenic effects of nitrosative deamination, which produces xanthine and inosine residues in DNA. Because of these results, we chose to investigate the protective role of endonuclease V in preventing stable HAP incorporation into DNA. It has been shown that the exonucleolytic proofreading (dnaQ) or the postreplicative mismatch repair system (mutHLS gene products) provide little or no protection against stable incorporation of HAP residues in DNA (50). Here we present data suggesting that endonuclease V initiates repair events at HAP residues in DNA and show that moa nfi double mutants exhibit elevated levels of transition mutations and increased cell survival compared to moa mutants.

Several studies have suggested that potentially lethal double-strand breaks (DSBs) can arise when replication forks traverse nicked DNA (19, 32, 39, 53). Therefore, the initiation of DNA repair by incision of damaged DNA can lead to cell death. E. coli possesses several well-studied enzymes for the repair of DSBs and restart of collapsed replication forks (for reviews, see references 9, 36, and 49). The data we present support the hypothesis that a molybdoenzyme converts HAP into a less toxic compound, that RdgB excludes 2′-deoxy-HAP triphosphate (dHAPTP) from replication precursor pools, that endonuclease V is the major endonuclease that recognizes HAP in DNA, and that nicking by endonuclease V at HAP residues leads to DSBs that require replication fork reactivation for continued DNA synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and phage used in this study are listed in Table 1. The medium used for growth was TY (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl per liter) and M9 minimal medium (40). M9 medium was sometimes supplemented with arginine (100 μg/ml), histidine-HCl (100 μg/ml), and thiamine-HCl (1 μg/ml). For cell dilutions and washings, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used (48). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: tetracycline hydrochloride, 20 μg/ml; kanamycin sulfate, 34 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml. HAP was purchased from U.S. Biochemical Corp. Cell growth was routinely monitored in a Klett-Summerson photocolorimeter with a green 54 filter; 30 Klett units were equivalent to 108 cells/ml.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| AB1157 | thr-1 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)62 hisG4(Oc) argE3(Oc) thi-1 ara-14 lacY1 galK2(Oc) xylA5 mtl-1 rpsL31(Strr) tsx-33 supE44 rac rfbD1 mgl-51 glnV44(As) rpoS396(Am) kdgK51 | Laboratory strain |

| BW1185 | KL16 nfi-1::Cat | B. Weiss |

| BW1524 | araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 deoC1 flhD5301 fruA25 gyrA219 non-9 relA1 rpsL150 | B. Weiss |

| BW1525 | BW1524 moa-250::Tn10d(Tc) | B. Weiss |

| BW9113 | φ80dIIlacBK1 ΔlacMS286 argE3 hisG4 zdh-201::Tn10 thi-1 rpsE (Spcr) glnV44(As) (Sull) mtl-1 tsx-29 | B. Weiss |

| CS85 | AB1157 ruvC53 eda-51::Tn10 | M. Marinus |

| CSH106 | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 proB F′ lacIZ proA+B+ | Cold Spring Harbor |

| JB3 | KL16 slrD300::Tn10 | KL16 × P1/MC1009 |

| JB7 | NEB51 slrD300::Tn10 | NEB51 × P1/JB3 |

| JB13.1 | NEB20 Δnfi | Link et al. (35) |

| JB13.2 | JB13.1 Δnfi (Tcs) | Spontaneous mutation |

| JB14 | JB13.2 Δnfi thiC39::Tn10 | JB13.2 × P1/NK5139 |

| JB42 | NEB55 nfi-1::Cat | NEB55 × P1/BW1185 |

| JB43 | NEB117 nfi-1::Cat | NEB117 × P1/BW1185 |

| JB44 | NEB119 nfi-1::Cat | NEB119 × P1/BW1185 |

| JB45 | NEB122 nfi-1::Cat | NEB122 × P1/BW1185 |

| JB46 | JB45 ΔrecA slrD300::Tn10 | JB45 × P1/JB7 |

| JB47 | NEB120 nfi-1::Cat | NEB120 × P1/BW1185 |

| JB48 | NEB118 nfi-1::Cat | NEB118 × P1/BW1185 |

| JC11824 | AB1157 lexA3 | M. Marinus |

| JC9239 | AB1157 recF143 | M. Marinus |

| KL16 | HfrPO45 thi-1 relA1 spoT1 | Laboratory strain |

| KM21 | AB1157 ΔrecBCD::Kan | M. Marinus |

| KW0.5 | CSH106 moeA::Kan | This study |

| KW1 | KL16 moeA::Kan | KL16 × P1/KW0.5 |

| MC1009 | araD139 Δ(araA-leu)7697 Δ(codB-lacI)3 galK16 galE15 λ− e14− recA56 srlD300::Tn10 relA1 rpsL150(Strr) spoT1 mcrB1 | R. Osuna |

| NEB1 | CSH106 rdgB3::Kan | CSH106 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB9 | CSH106 moa-250::Tn10d(Tc) | CSH106 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB10 | NEB9 rdgB3::Kan | NEB9 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB18 | CSH106 nfi-1::Cat | CSH106 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB19 | NEB9 nfi-1::Cat | NEB9 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB20 | KL16 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | KL16 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB21 | AB1157 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | AB1157 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB32 | NEB18 rdgB3::Kan | NEB18 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB41 | NEB19 rdgB3::Kan | NEB19 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB51 | KL16 ΔrecA | Link et al. (35) |

| NEB55 | NEB21 priA1::Kan | NEB21 × P1/PN104 |

| NEB117 | NEB21 ΔrecBCD::Kan | NEB21 × P1/KM21 |

| NEB118 | JC9239 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | JC9239 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB119 | JC11824 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | JC11824 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB120 | CS85 moeA::Kan | CS85 × P1/KW1 |

| NEB122 | AB1157 moeA::Kan | AB1157 × P1/KW1 |

| NEB123 | BW9113 (Tcs) | Spontaneous mutation |

| NEB124 | NEB123 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | NEB123 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB125 | NEB123 rdgB3::Kan | NEB123 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB126 | NEB124 rdgB3::Kan | NEB124 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB127 | NEB124 nfi-1::Cat | NEB124 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB128 | NEB126 nfi-1::Cat | NEB126 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB129 | NEB125 nfi-1::Cat | NEB125 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB134 | NO120 rdgB3::Kan | NO120 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB135 | NEB134 nfi-1::Cat | NEB134 × P1/BW1185 |

| NEB136 | NO120 moa-250::Tn10d(Tcr) | NO120 × P1/BW1525 |

| NEB137 | NEB136 (Tcs) | Spontaneous mutation |

| NEB138 | NEB137 Δnfi thiC39::Tn10 | NEB137 × P1/JB14 |

| NEB139 | NEB137 rdgB3::Kan | NEB137 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB140 | NEB138 rdgB3::Kan | NEB138 × P1/RPC133 |

| NEB152 | NEB122 ΔrecA slrD300::Tn10 | NEB122 × P1/JB7 |

| NK5139 | λ− Δ(rrnD-rrnE)1 thiC39::Tn10 | CGSC |

| NO120 | Δ(argF-lac)205 relA1 thi-1 sulA::Mu d(Ap lacX Camr) cps | Laboratory strain |

| PN104 | garB10 fhuA22 lacZ phoA4(Am) λ−ompF627(T2r) fadL701(T2r) relA1 pit-10 dinD1::Mud(Ap lac) spoT1 priA1::Kan rrnB2 mcrB1 creC510 | CGSC |

| RPC133 | AB1157 rdgB3::Kan | Laboratory strain |

Strain construction.

Selection for tetracycline-sensitive clones was performed as described previously (3). ΔrecA and Δnfi strains were constructed by the method of Link et al. (35). P1-mediated transductions were performed as described previously (56). recA alleles were introduced into appropriate recipients by cotransduction with the linked slrD300::Tn10 allele (11). Δnfi alleles were introduced into appropriate recipients by cotransduction with the linked thiC39::Tn10 allele (41). All strains containing these deletions were verified by PCR analysis (35). The moeA::Kan strain was constructed by mutagenesis with an EZ::TN transposon (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, an EZ::TN library was constructed in CSH106, and HAP-dependent mutators were selected on lactose minimal medium plates after exposure to HAP. Identification of the genes inactivated by transposition was performed by DNA sequence analysis.

Measurement of HAP cytotoxicity.

Fresh overnight cultures of strains to be tested (0.35 ml) were diluted into 35 ml of fresh TY medium and grown with aeration at 37°C. When the cultures reached a cell density of 2 × 108/ml, 5-ml aliquots were transferred to separate flasks and incubated in the presence or absence of HAP for 1 h. One-milliliter aliquots were removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and immediately placed on ice. Cells were diluted to appropriate cell densities with PBS, plated on TY plates, and incubated at 37°C. Surviving colonies were scored the next day. For this assay the wild-type strain was CSH106, and all strains tested were derivatives of CSH106. Bacterial strains were also assayed for HAP sensitivity by the gradient plate method. For the gradient plate assay, the wild-type strain was AB1157 and all strains tested were derivatives of AB1157. Agar media containing linear concentration gradients of HAP were prepared by the method of Cunningham et al. (12). Plates were stained with acridine orange solution (0.2 mg/ml in ethanol) and photographed with UV exposure using a 590-nm optical filter (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Measurement of mutant frequencies.

Mutant frequencies were measured by a modification of the procedure of Cupples and Miller (13). Fresh overnight cultures of derivatives of CSH106 (0.35 ml) were diluted into 35 ml of fresh TY medium and grown with aeration at 37°C. When the cultures reached a cell density of 2 × 108/ml, 5-ml aliquots were transferred to separate flasks and incubated in the presence or absence of HAP for 1 h. One-milliliter aliquots were removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and immediately placed on ice. Cells were diluted to appropriate cell densities with PBS and plated on minimal medium plates containing 0.4% lactose and on TY plates. TY and lactose minimal medium plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 and 42 h, respectively, to measure viable cells and Lac+ revertants.

Measurement of recombination proficiency.

Intrachromosomal recombination was measured by a modification of the procedure of Zieg et al. (63) in derivatives of BW9113. A 35-ml volume of fresh TY medium was inoculated with a single colony of the strain to be tested and grown with aeration at 37°C. When the cultures reached a cell density of 108/ml, 5-ml aliquots were transferred to separate flasks and incubated in the presence or absence of HAP for 1 h. One-milliliter aliquots were removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and immediately placed on ice. Cells were diluted to appropriate cell densities with PBS, plated on minimal medium plates containing 0.4% lactose, and incubated at 37°C for 42 h. Lac+ recombinants were scored.

Measurement of SOS induction.

Fresh overnight cultures of derivatives of NO120 (0.35 ml) were diluted into 35 ml of fresh TY medium and grown with aeration at 37°C. When the cultures reached a cell density of 2 × 108/ml, 5-ml aliquots were transferred to separate flasks and incubated in the presence or absence of HAP for 1 h. Aliquots were removed, and β-galactosidase levels were determined by the method of Miller (40).

RESULTS

HAP cytotoxicity.

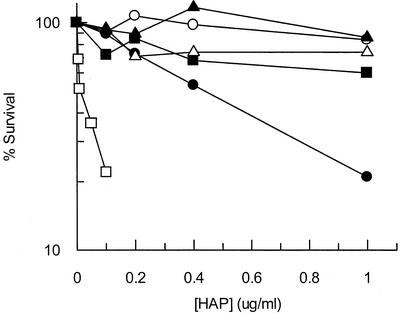

To assess the role of gene products we suspected to be required for the exclusion of purine base analogs from DNA, we determined whether strains lacking functional gene products displayed a significant change in HAP sensitivity. For the cytotoxicity assay, we exposed exponentially growing moa (MGD-deficient) cells to various concentrations of HAP for 1 h. Cytotoxicity tests showed that wild-type cells were not sensitive to HAP at any concentration tested up to 1 μg/ml, while moa mutants were sensitive to HAP and displayed about 20% survival after exposure to 1 μg of HAP/ml (Fig. 1). moa rdgB mutants were significantly more sensitive to HAP than the single moa mutant and displayed approximately 20% survival after exposure to 0.1 μg of HAP/ml. This result suggests a synergy between a HAP-detoxifying molybdoenzyme and RdgB in HAP detoxification. Figure 1 shows that endonuclease V deficiency dramatically reversed the HAP-sensitive phenotype of moa and moa rdgB mutants at all concentrations tested (greater than 70% survival after exposure to 1 μg of HAP/ml). Finally, we demonstrated that an rdgB mutant is HAP resistant, showing that the moa mutation is required for HAP sensitivity. Our results suggest that an MGD-dependent enzyme is the major determinant of HAP resistance and that the RdgB protein plays a role in excluding HAP from DNA, while endonuclease V plays a role in removing HAP residues from DNA.

FIG. 1.

Relative HAP sensitivity of E. coli strains mutant for suspected purine base analog-metabolizing enzymes. Mid-log-phase cells were exposed to various concentrations of HAP for 1 h at 37°C. Data were recorded as percent survival at the various HAP concentrations. Each data point represents one bacterial culture. Symbols: ○, CSH106 (wild type); •, NEB9 (moa); □, NEB10 (moa rdgB); ▪, NEB19 (moa nfi); ▵, NEB41 (moa rdgB nfi); ▴, NEB1 (rdgB).

Mutagenesis assays.

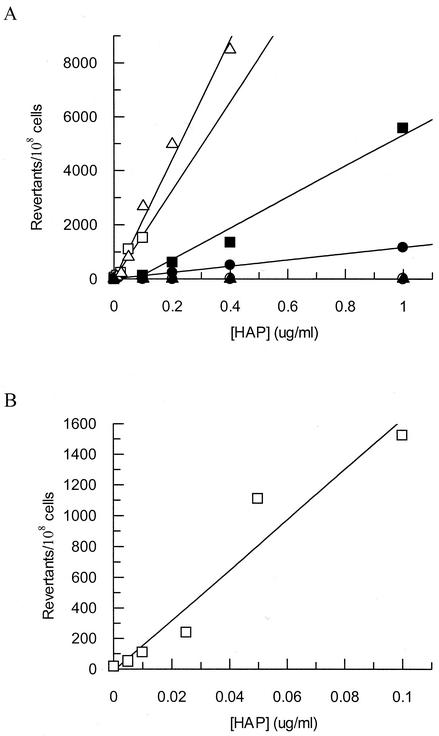

Mutagenesis assays demonstrated that mutants deficient in MGD biosynthesis, RdgB protein, and endonuclease V exhibit increased mutation frequencies. This assay employed an E. coli strain that had been engineered to detect an A:T to G:C transition mutation at one specific nucleotide position in the lacZ gene. This specific mutation event results in a reversion to the Lac+ phenotype, allowing measurement of the frequency of A:T to G:C transition mutations by plating on minimal lactose plates for mutants and TY plates for viable counts (13). For this assay, the wild-type mutation frequencies with or without HAP were extremely low, and the baseline value for the wild type was 1 revertant/108 CFU. Hence, moa mutants showed a 1,000-fold increase in the frequency of A:T to G:C transition mutations compared to the wild type at the highest HAP concentration tested (1 μg/ml), while moa nfi mutants showed a 5,500-fold increase in mutation frequency over wild type (Fig. 2A). moa rdgB mutants are extremely sensitive to HAP and were assayed at much lower concentrations of HAP to prevent excessive killing (Fig. 2B). At 0.1 μg of HAP/ml, moa rdgB mutants exhibited a 1,500-fold increase in mutation frequency over wild type, whereas moa mutants showed a 100-fold increase over wild type at this concentration. moa rdgB nfi mutants are “supermutators” with respect to HAP, and mutation frequencies for this strain departed from linearity at concentrations greater than 0.4 μg/ml. Nonetheless, at this concentration moa rdgB nfi mutants showed an increase in mutation frequency of over 8,000-fold compared to wild type (Fig. 2A). When the moa, rdgB, and nfi gene products are deficient, the cell is unable to prevent HAP incorporation into DNA or to initiate subsequent repair. Therefore, this strain's DNA might be expected to be highly substituted with HAP, as suggested by the supermutator phenotype upon HAP exposure. By comparison, an rdgB nfi strain showed no HAP-dependent mutagenesis, again demonstrating that a moa mutation causes the most significant sensitivity to HAP.

FIG. 2.

(A) HAP-induced mutagenesis frequencies of E. coli strains mutant for suspected purine base analog-metabolizing enzymes. Mid-log-phase cells were exposed to various concentrations of HAP for 1 h at 37°C. Results for wild type and rdgB nfi were indistinguishable. (B) HAP-induced mutagenesis frequencies of NEB10 (moa rdgB) at very low HAP concentrations. Each data point represents one bacterial culture. Symbols: ○, CSH106 (wild type); •, NEB9 (moa); □, NEB10 (moa rdgB); ▪, NEB19 (moa nfi); ▵, NEB41 (moa rdgB nfi); ▴, NEB32 (rdgB nfi).

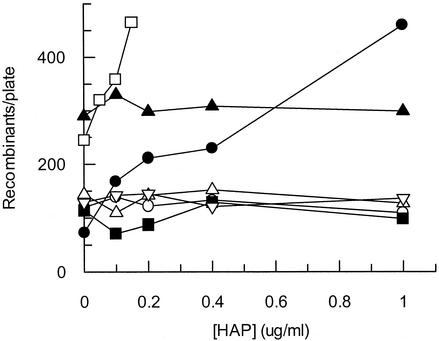

Recombination assays.

Clyman and Cunningham reported that an rdgB mutant showed enhanced intrachromosomal recombination (6). The synthetic lethality of recA rdgB double mutants suggests that in the absence of RdgB a lesion develops in DNA that must be repaired by a RecA-dependent recombinational event (6). Therefore, we reasoned that if RdgB has activity against dHAPTP, recombination frequencies should increase in a moa rdgB mutant exposed to HAP compared to a moa mutant. Furthermore, if endonuclease V has activity against HAP-containing DNA, as the cytotoxicity and mutagenesis assays indicate, then recombination frequencies in nfi mutants exposed to HAP should be decreased, due to lack of endonuclease V-catalyzed nicking at HAP residues in DNA.

The recombination assay we used measures the frequency at which two nontandem partially deleted lac operons recombine to produce Lac+ progeny (27, 63). For this assay, early-log-phase cells were exposed to HAP for 1 h at concentrations that yielded a linear dose response. Figure 3 shows that the recombination frequency of a moa mutant increased from less than 100 Lac+ colonies per plate without HAP to over 450 Lac+ colonies with exposure to 1 μg of HAP/ml. Conversely, the wild-type tester strain showed no increase in recombination frequency and produced about 100 Lac+ colonies per plate for all HAP concentrations tested. This result suggests that the incorporation of HAP residues into polymerizing DNA results in an increased frequency of homologous recombination. Transducing a moa strain to rdgB results in a synergistic effect on intrachromosomal recombination with increasing HAP, and this strain produced over 450 Lac+ colonies per plate at 0.15 μg of HAP/ml. An rdgB strain showed a twofold increase in recombination frequency over wild type in the absence of HAP, as previously reported (6), but the recombination frequency was not elevated in the presence of HAP. When any of these strains were transduced to nfi, the recombination frequency decreased to wild-type levels (about 100 Lac+ colonies per plate) under all conditions tested (Fig. 3). These data support the notion that the incorporation of HAP into DNA generates lesions that stimulate recombination and that these lesions appear to arise from the initiation of DNA repair events, because recombination frequencies are dramatically reduced when endonuclease V is absent. Furthermore, the rdgB data in Fig. 3 suggest that some endogenous noncanonical purine is incorporated into DNA in the absence of the RdgB protein and that this purine is recognized by endonuclease V.

FIG. 3.

Recombination frequencies of E. coli strains mutant for suspected purine base analog-metabolizing enzymes upon HAP exposure. Early-log-phase cells were exposed to various concentrations of HAP for 1 h at 37°C. Each data point represents one bacterial culture. Symbols: ○, NEB123 (wild type); •, NEB124 (moa); □, NEB126 (moa rdgB); ▪, NEB127 (moa nfi); ▵, NEB128 (moa rdgB nfi); ▴, NEB125 (rdgB); ▿, NEB129 (rdgB nfi).

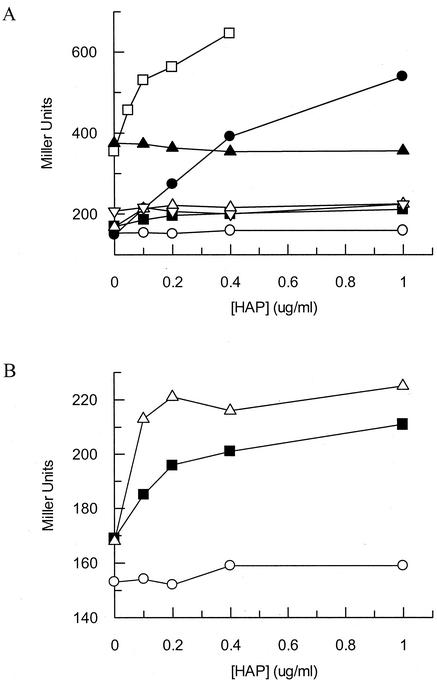

SOS induction assays.

The SOS assay employs a β-galactosidase reporter gene fused to the promoter of the sulA gene, an SOS-inducible gene (25). Clyman and Cunningham reported that rdgB mutants were induced for the SOS response (6). We have examined the ability of HAP to induce the SOS response in various mutants deficient in HAP detoxification or repair. For this assay, cells were grown to mid-log phase and incubated with HAP for 1 h at HAP concentrations that prevent excessive killing. Figure 4A shows that wild-type cells showed no increase in SOS induction in the presence of HAP, yielding a baseline value of about 150 Miller units. Conversely, transducing the tester strain to moa resulted in an increase in SOS induction of greater than threefold (540 Miller units) at 1 μg of HAP/ml. Transducing a moa strain to rdgB resulted in a synergistic effect on SOS induction with increasing HAP, and the moa rdgB double mutant displayed a fourfold increase in SOS induction compared to the wild-type tester strain at only 0.4 μg of HAP/ml. An rdgB strain showed a twofold increase in SOS induction in the absence of HAP, as previously reported (6), but the level of SOS expression was not increased in the presence of HAP. Transduction of these strains to nfi resulted in reduced SOS induction for all strains and conditions tested (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that the inability of nfi mutants to incise HAP-containing DNA prevents the formation of a DNA structure that signals SOS induction. In this assay, we noted that the introduction of an nfi mutation did not completely restore SOS induction levels of moa mutants to wild-type levels (Fig. 4B). In fact, there appeared to be a small induction of the SOS response caused by HAP in nfi mutants. This induction occurred at lower HAP concentrations in an rdgB strain, as expected. This result suggests that there is some other enzyme in E. coli that has the ability to incise HAP-containing DNA, but it is either very inefficient or present at very low levels.

FIG. 4.

(A) SOS induction of E. coli strains mutant for suspected purine base analog-metabolizing enzymes upon HAP exposure. Mid-log-phase cells were exposed to various concentrations of HAP for 1 h at 37°C. (B) Expanded view of induction in three strains. Each data point represents one bacterial culture. Symbols: ○, NO120 (wild type); •, NEB137 (moa); □, NEB139 (moa rdgB); ▪, NEB138 (moa nfi); ▵, NEB140 (moa rdgB nfi); ▴, NEB134 (rdgB); ▿, NEB135 (rdgB nfi).

HAP cytotoxicity of lexA3 mutants.

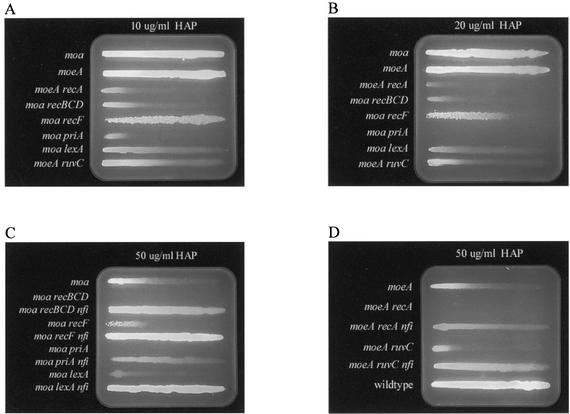

RecA-activated self-cleavage of the LexA repressor initiates the SOS response (14). Subsequently, induction of the SOS response results in the upregulation of dozens of DNA repair and damage tolerance genes. A lexA3 mutant is incapable of self-cleavage, and lexA3 strains do not initiate the SOS response (14). Figures 5A and B show that moa lexA3 mutants plated on a linear gradient of HAP showed increased HAP sensitivity compared to moa mutants. This suggests that induction of the SOS response is essential for repair of HAP lesions. Furthermore, HAP gradient plates showed that inactivation of the endonuclease V gene can dramatically reverse the extreme HAP-sensitive phenotype of a moa lexA double mutant (Fig. 5C). Therefore, it appears that in the absence of endonuclease V the need for an induced SOS state is relieved for MGD-deficient strains in the presence of HAP.

FIG. 5.

Gradient plate test for HAP sensitivity. The length of a line of cell growth is a measure of the strain's resistance to HAP (MIC). (A) The agar (50 ml) contained a total of 50 μl of a 5-mg/ml HAP solution distributed in a linear gradient increasing from left to right. The strains used (top to bottom) were NEB21, NEB122, NEB152, NEB117, NEB118, NEB55, NEB119, and NEB120. (B) Same experiments as shown in panel A, except that 100 μl of a 5-mg/ml HAP solution was used. (C) The agar (50 ml) contained a total of 250 μl of a 5-mg/ml HAP solution distributed in a linear gradient increasing from left to right. The strains used (top to bottom) were NEB21, NEB117, JB43, NEB118, JB48, NEB55, JB42, NEB119, and JB44. (D) The agar (50 ml) contained a total of 250 μl of a 5-mg/ml HAP solution distributed in a linear gradient increasing from left to right. The strains used (top to bottom) were NEB122, NEB152, JB46, NEB120, JB47, and AB1157.

DSBR and replication fork reactivation.

Processes of homologous recombination are known to protect cells against DNA lesions (such as nicks in DNA) that can collapse replication forks (15, 18, 39). Homologous recombination processes in E. coli are thought to be initiated by either single-stranded gaps in DNA or by double-stranded ends. DSB repair (DSBR) is known to utilize the RecBCD repair pathway, while the recFOR gene products have been shown to initiate repair of single-stranded gaps (1, 9, 24, 37, 55). Because we saw an increase in recombination frequencies in moa mutants exposed to HAP, we wished to determine if single-stranded gaps or DSBs initiated recombinational processes. Therefore, we compared the relative sensitivities of recBCD and recF mutant cells plated on a linear gradient of HAP. HAP gradient plates showed that moa recBCD mutants are extremely sensitive to HAP and display a MIC of about 2 μg of HAP/ml, while moa recF mutants are only slightly more sensitive to HAP than moa mutants and these strains display MICs of about 10 and 15 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 5A, B, and C). These results suggest that exposure of moa strains to HAP results in DSBs, which must be repaired by the RecBCD repair pathway.

Processing of double-strand ends by the recBCD gene products results in single-stranded 3′-terminated DNA that, when bound by RecA, becomes a substrate for strand invasion of sister duplex DNA (8). Strand invasion can result in a Holliday junction, allowing DNA polymerases to traverse the region of the DSB. Resolution of the Holliday junction can be achieved by the RuvABC resolvase. Subsequently, loading of the replication restart primosome can restart replication (8). Because of the intimate involvement of RecA and the RuvABC resolvase in DSBR, we investigated the relative HAP sensitivities of moeA recA and moeA ruvC double mutants with that of a single moeA mutant to further determine the importance of DSBR for cell survival. The HAP gradient plates in Fig. 5A and B show that both RecA and RuvC confer protection against HAP killing, because moeA recA and moeA ruvC double mutants displayed MICs of less than 2 μg/ml and roughly 4 μg/ml, respectively, compared to a MIC of 15 μg/ml for a moeA strain. The more modest increase in HAP sensitivity for moeA ruvC double mutants compared to that in the other DSBR mutants can best be explained by the redundancy the RuvABC resolvase and RecG DNA helicases, which can both resolve Holliday junctions. The extreme sensitivity of the moeA recA mutant underscores the dependence of homologous recombination and induction of the SOS response for survival of MGD-deficient strains exposed to HAP. Due to incompatibility of available antibiotic resistance markers, we present AB1157 derivatives carrying either a moa or a moeA mutation. As we have shown in Fig. 5B and as reported by Schaaper and colleagues, these strains show similar sensitivities to HAP (29).

Replication fork reactivation is another process involving homologous recombination that can restart collapsed replication forks (10, 38, 49). Replication fork reactivation is directed by the priA gene product, a DNA-binding protein and 3′→5′ DNA helicase (38). PriA recognizes D-loops, the initial structure created by RecA- and RecBCD-mediated strand invasion of sister duplex DNA. Binding of PriA to the D-loop leads to the formation of a PriA-PriB-DnaT-D-loop complex that facilitates assembly of the primosome and subsequent replication fork reactivation (38). Because we suspected the accumulation of DSBs resulting from replication forks traversing endonuclease V-nicked HAP-containing DNA to be the lethal event in HAP toxicity, we suspected replication restart mutants to be extremely HAP sensitive. PriA is essential for replication fork reactivation (10). Therefore, we investigated the relative HAP sensitivity of a moa priA double mutant compared to that of a single moa mutant. We found that moa priA double mutants were extremely HAP sensitive and displayed a MIC of less than 2 μg/ml compared to a MIC of 15 μg/ml for moa mutants (Fig. 5A). These data suggest that replication restart plays an important role in cell survival upon HAP exposure and that replication forks encounter an increased number of lesions that lead to replication fork collapse when HAP is not detoxified in vivo.

Inactivation of the endonuclease V gene rescues the extreme HAP-sensitive phenotype of DSBR and replication fork reactivation mutants. Transduction of recBCD, recA, ruvC, and priA mutants in an MGD-deficient background to nfi resulted in a significant reversal of the HAP-sensitive phenotype for all strains tested (Fig. 5C and D). Transducing moa recBCD to nfi resulted in a rescue of HAP sensitivity, and this strain displayed a MIC of about 40 μg/ml, which is about a 20-fold rescue in HAP sensitivity compared to a MIC of about 2 μg of HAP/ml for moa recBCD cells. Transducing moa priA double mutants to nfi resulted in a rescue of HAP sensitivity, and this strain displayed a MIC of about 30 μg/ml. Compared to the MIC of less than 2 μg/ml displayed by a moa priA strain, the triple mutant showed at least a 15-fold rescue in HAP sensitivity. Plating moeA recA nfi triple mutants on a 50-μg/ml HAP gradient plate resulted in a MIC of about 25 μg/ml. This is at least a 10-fold decrease in sensitivity compared to a moeA recA strain, which shows a MIC of less than 2 μg/ml. Therefore, the moeA recA mutant showed a slightly more modest rescue of HAP sensitivity. This can probably best be explained by the ubiquitous role of RecA in all homologous recombinational processes and its role in induction of the SOS response. Transducing a moeA ruvC strain to nfi resulted in a MIC about 40 μg/ml. Comparing this triple mutant to a moeA ruvC double mutant, which displayed a MIC of 4 μg/ml, we observed a 10-fold rescue of HAP sensitivity. Finally, a moa recF nfi triple mutant showed no HAP sensitivity under the conditions tested, as expected if RecF is not required for HAP-induced recombination. These results support the idea that the initiation of repair of HAP lesions by endonuclease V can lead to cell death by the accumulation of DSBs in DNA that could occur when replicative polymerases traverse endonuclease V-nicked DNA.

DISCUSSION

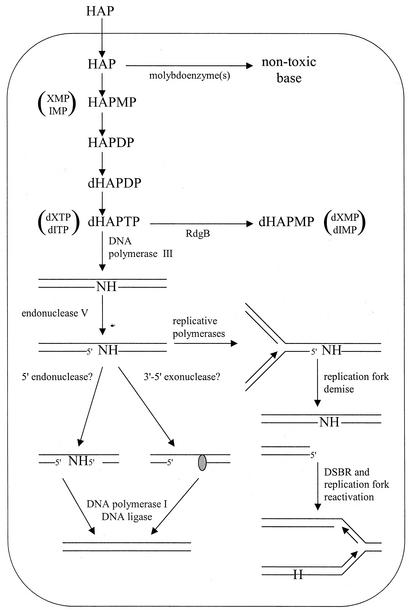

The experiments presented in this paper lead us to propose a model for a system that prevents incorporation of HAP into DNA at three different points in nucleic acid metabolism (Fig. 6). At the level of free base, a yet-unidentified molybdoenzyme(s) is responsible for converting HAP into a nontoxic substance via an unknown detoxifying reaction, as shown by Kozmin et al. (29) and the results presented in this paper. To date, nine E. coli molybdoenzymes have been described, many of which display activity only under anaerobic conditions and therefore are unlikely to possess the HAP-detoxifying activity we saw under our aerobic experimental conditions. Several strains bearing mutations in genes for putative HAP-detoxifying molybdoenzymes have been tested by our laboratory and the Schaaper laboratory (29), and they show no increase in HAP sensitivity compared to their isogenic wild-type parental strains. These include strains bearing mutations in genes that encode the dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase, and biotin sulfoxide reductase (29). Clement and Kunze have shown that mammalian xanthine oxidase is capable of converting HAP to adenine (5). Homology searches of the E. coli genome for xanthine oxidase reveal three open reading frames with sequence similarity to mammalian xanthine oxidases (33). These data suggest that one or more of the three potential xanthine oxidases could be candidates for the HAP detoxification activity. Our lab has constructed an E. coli strain in which all three putative xanthine oxidase genes have been inactivated, and this strain shows no HAP sensitivity (data not shown). Although all the known E. coli molybdoenzymes have not been tested, the best candidates have been tested, and the identity of the HAP-detoxifying molybdoenzyme(s) still remains unknown.

FIG. 6.

Model for excluding HAP and endogenous purine base analogs from DNA. Symbols: H = HAP, N = any base.

In the absence of the detoxifying molybdoenzyme(s), HAP apparently can enter the nucleotide pools by conversion to HAP-monophosphate (HAPMP) by at least one of the purine phosphoribosyltransferases. Subsequently, it appears that HAPMP can be a substrate for AMP kinase. HAP-diphosphate would then follow the general pathway of 2′-OH reduction by ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase and phosphorylation by nucleoside diphosphokinase, resulting in dHAPTP (62). Structure-based identification of the RdgB homolog in M. jannaschii, Mj0226, and biochemical studies of the protein have shown Mj0226 to be a deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphatase having substrate specificity for noncanonical purine nucleoside triphosphates (26). Our data suggest that RdgB is capable of efficiently hydrolyzing dHAPTP. Surprisingly, Chung et al. have reported that Mj0226 displays a substrate specificity for dHAPTP that is at least 1,500-fold less than that for xanthine triphosphate (XTP), at least 1,000-fold less than that for dITP, and actually lower than that for dGTP (4). However, in our hands, the pyrophosphatase activity of RdgB against GTP can be significantly inhibited by addition of HAP to the reaction (unpublished results). Our inhibition results suggest that dHAPTP may be a good substrate for the RdgB protein. Furthermore, mutants of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog, HAM1, show hypersensitivity to HAP and HAP hypermutability, again suggesting that dHAPTP is a substrate for RdgB and its homologs (42, 43). The discrepancy between our results and those of Chung et al. suggests that the substrate specificity of RdgB and its homologs needs to be reinvestigated.

Should HAP be incorporated into replicating DNA, it would become a substrate for endonuclease V. Inactivation of the endonuclease V gene shows an almost complete reversal of the sensitivity, hyperrecombinogenic, and SOS-induced phenotypes of moa and moa rdgB mutants exposed to HAP, but it results in a dramatic increase in mutational frequencies upon HAP exposure. These results indicate that endonuclease V is the major enzyme that recognizes HAP in DNA and initiates repair of these lesions. Endonuclease V-initiated repair may be a slow process, resulting in long-lived repair intermediates that would be capable of both providing substrates for recombinational repair and inducing the SOS response. It is interesting that the repair intermediates generated by endonuclease V nicking at HAP lesions are the direct cause of the HAP-sensitive, hyperrecombinogenic, and SOS-induced phenotypes of moa and moa rdgB strains. Therefore, endonuclease V nicking of HAP, which is nontoxic, results in a potentially toxic lesion.

There are two interesting distinctions between E. coli and S. cerevisiae that should be noted here. First, S. cerevisiae HAM1 mutants show hypersensitivity to HAP, whereas E. coli rdgB mutants show no HAP sensitivity (42). This may suggest that in E. coli the detoxifying activity of RdgB is backup to the molybdoenzyme detoxifying activity with respect to HAP, in contrast to yeast where the HAM1 protein is the major HAP detoxifying enzyme. Secondly, S. cerevisiae, which does not possess an endonuclease V homolog, shows no increase in recombination when exposed to HAP (43). This result further supports that endonuclease V in E. coli recognizes HAP residues in DNA and that the initiation of repair by endonuclease V promotes recombination.

Endonuclease V nicks the lesion-containing DNA strand at the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to the lesion (58). An endonuclease V-initiated repair event has the potential to result in a DSB if a replication fork traverses an endonuclease V-nicked lesion. Results presented here demonstrate that exposure of MGD-deficient strains to HAP results in an increase of endonuclease V-sensitive sites in DNA, which can lead to DSBs that must be repaired by the RecBCD repair pathway. Recombinational repair intermediates processed by the RecBCD complex can resume DNA replication via DSBR and replication fork reactivation (8, 10, 38, 49).

The results presented here are very similar to the results reported by Guo and Weiss (17). They showed that an nfi mutant was more resistant to nitrous acid than wild type and suggested that endonuclease V could create DSBs by acting on deaminated bases. Our results are also similar to those of Spek et al. (53, 54). They presented data showing that AP endonuclease-deficient cells can be protected from NO· toxicity by inactivation of uracil (Ung) or formamidopyrimidine (Fpg) DNA glycosylases. Their data showed that the activity of these DNA glycosylases on NO·-induced base damage resulted in the accumulation of base excision repair intermediates that are capable of causing DSBs and subsequently require the action of RecBCD for DSBR (53, 54). Taken together, these studies show that processes that repair and prevent lesions in DNA require a coordinated repair scheme, and deficiencies in the processes that maintain genomic integrity can result in cell death.

It is currently unknown what cellular components are involved in processing repair intermediates resulting from endonuclease V nicking of DNA. Endonuclease V activity at HAP residues would merely nick the lesion-containing DNA strand one base 3′ of the HAP residue. Therefore, it seems reasonable that a 3′→5′ exonuclease would be needed to remove the lesion from DNA (20). Alternatively, endonuclease V could recruit another endonuclease to cleave the lesion-containing strand 5′ of the lesion. Either scenario would additionally require DNA polymerase I and DNA ligase (20).

Our results beg the question, what is the biological significance of this pathway? E. coli in its natural environment would not be expected to encounter very much HAP, if any at all. Indeed, it seems unreasonable that the need to sanitize purine pools of HAP or dHAPTP is so great that a system would evolve simply for that purpose. Furthermore, homology searches with the RdgB and endonuclease V amino acid sequences reveal that this system is evolutionarily conserved throughout phylogeny, from bacteria to humans (26, 28, 30, 34). Therefore, we propose that this system has evolved to exclude endogenous purine base analogs, such as dITP and dXTP, from replication precursor pools and DNA. IMP and XMP are both intermediates in the biosynthesis of dATP and dGTP and therefore may be present in cells in appreciable quantities (62). Spontaneous deamination of adenine and guanine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides also can lead to the production of hypoxanthine and xanthine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides, respectively, in vivo (51, 52). Several lines of evidence support our model. Chung et al. have shown that the best substrates for Mj0226 are XTP and dITP and that these substrates, respectively, display substrate specificities that are at least 150- and 100-fold greater than the best canonical purine nucleotide, GTP (4). They also report that RdgB (Ec197) shows a 65-fold-greater activity against dITP than dGTP (4). Similarly, the human homolog, human ITP pyrophosphatase, shows pyrophosphatase activity against dITP and XTP that is about 10-fold better than the activity against dGTP (34). These results suggest that RdgB and its homologs are responsible for removing these endogenous purine nucleotide triphosphates from purine pools. The Kow laboratory has shown that endonuclease V is active against deoxyinosine and deoxyxanthosine residues in double-stranded DNA (20, 60). Clyman and Cunningham reported that an rdgB strain shows elevated levels of recombination and is partially induced for the SOS response (6). In this paper we have shown that transducing an rdgB strain to nfi results in a decrease in the SOS-induced and hyperrecombinogenic phenotypes to near wild-type levels in the absence of HAP (Fig. 3 and 4A). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that endogenous noncanonical deoxynucleotide triphosphates persist in the cell when RdgB is absent, that these deoxynucleotide triphosphates are incorporated into DNA, and that they are substrates for endonuclease V. Subsequently, endonuclease V nicking at these residues leads to the observed phenotypes in the absence of HAP. Figure 6 shows that our model for the detoxification of endogenous purine base analogs is similar to the model for HAP detoxification. This model is an extension of the models proposed by Noskov et al. (42) and Kow (28).

This study has shown that a system exists in E. coli to help cells cope with the exogenous purine base analog HAP and suggests that the system has been conserved throughout phylogeny to remove endogenous purine base analogs from purine nucleotide pools and to excise endogenous purine base analogs that have been incorporated into DNA by replicative polymerases.

The system we have described is similar to two other systems that prevent the incorporation of uracil and 8-oxoguanine into DNA. In these systems, the deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate pool is sanitized through the action of dUTPase (23) and the MutT protein (2), respectively. If uracil or 8-oxoguanine is incorporated into DNA, it is removed by the repair enzymes uracil-DNA glycosylase (31) and the MutM protein (fapy-DNA glycosylase) (16), respectively. In both cases it appears that the presence of dUTP and 8-oxoguanine triphosphate is significant in the cell, and it is known that the incorporation of these nucleotides into DNA by polymerases occurs readily (16, 31). The fact that cells have a similar system for purine base analogs suggests that the occurrence of base analog nucleotides is widespread and that these nucleotides are easily incorporated into DNA by replicative polymerases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB-0115188 to R.P.C.

We thank Mary Berlyn of the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, Alexandros Kiupakis, Martin Marinus, Robert Osuna, Roel Schaaper, and Bernard Weiss for providing bacterial strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, D. A., and S. C. Kowalczykowski. 2000. Facilitated loading of RecA protein is essential to recombination by RecBCD enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12261-12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatnagar, S. K., L. C. Bullions, and M. J. Bessman. 1991. Characterization of the mutT nucleoside triphosphatase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266:9050-9054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochner, B. R., H. C. Huang, G. L. Schieven, and B. N. Ames. 1980. Positive selection for loss of tetracycline resistance. J. Bacteriol. 143:926-933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, J. H., J. H. Back, Y. I. Park, and Y. S. Han. 2001. Biochemical characterization of a novel hypoxanthine/xanthine dNTP pyrophosphatase from Methanococcus jannaschii. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:3099-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clement, B., and T. Kunze. 1992. The reduction of 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine to adenine by xanthine oxidase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 44:1501-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clyman, J., and R. P. Cunningham. 1987. Escherichia coli K-12 mutants in which viability is dependent on recA function. J. Bacteriol. 169:4203-4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clyman, J., and R. P. Cunningham. 1991. Suppression of the defects in rdgB mutants of Escherichia coli K-12 by the cloned purA gene. J. Bacteriol. 173:1360-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, M. M. 2001. Historical overview: searching for replication help in all of the rec places. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8173-8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox, M. M. 1999. Recombinational DNA repair in bacteria and the RecA protein. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 63:311-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox, M. M., M. F. Goodman, K. N. Kreuzer, D. J. Sherratt, S. J. Sandler, and K. J. Marians. 2000. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature (London) 404:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csonka, L. N., and A. J. Clark. 1980. Construction of an Hfr strain useful for transferring recA mutations between Escherichia coli strains. J. Bacteriol. 143:529-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham, R. P., S. M. Saporito, S. G. Spitzer, and B. Weiss. 1986. Endonuclease IV (nfo) mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 168:1120-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cupples, C. G., and J. H. Miller. 1989. A set of lacZ mutations in Escherichia coli that allow rapid detection of each of the six base substitutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5345-5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedberg, E. C., G. C. Walker, and W. Siede. 1995. DNA repair and mutagenesis, p. 407-464. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 15.George, J. W., B. A. Stohr, D. J. Tomso, and K. N. Kreuzer. 2001. The tight linkage between DNA replication and double-strand break repair in bacteriophage T4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8290-8297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gros, L., M. K. Saparbaev, and J. Laval. 2002. Enzymology of the repair of free radicals-induced DNA damage. Oncogene 21:8905-8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo, G., and B. Weiss. 1998. Endonuclease V (nfi) mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 180:46-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haber, J. E. 2000. Partners and pathways repairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet. 16:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanawalt, P. C. 1966. The UV sensitivity of bacteria: its relation to the DNA replication cycle. Photochem. Photobiol. 5:1-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, B., H. Qing, and Y. W. Kow. 2000. Deoxyxanthosine in DNA is repaired by Escherichia coli endonuclease V. Mutat. Res. 459:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hille, R. 1996. The mononuclear molybdenum enzymes. Chem. Rev. 96:2757-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill-Perkins, M., M. D. Jones, and P. Karran. 1986. Site-specific mutagenesis in vivo by single methylated or deaminated purine bases. Mutat. Res. 162:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochhauser, S. J., and B. Weiss. 1978. Escherichia coli mutants deficient in deoxyuridine triphosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 134:157-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horii, Z., and A. J. Clark. 1973. Genetic analysis of the recF pathway to genetic recombination in Escherichia coli K12: isolation and characterization of mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 80:327-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huisman, O., and R. D'Ari. 1981. An inducible DNA replication-cell division coupling mechanism in E. coli. Nature (London) 290:797-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang, K. Y., J. H. Chung, S. H. Kim, Y. S. Han, and Y. Cho. 1999. Structure-based identification of a novel NTPase from Methanococcus jannaschii. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:691-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konrad, E. B. 1977. Method for the isolation of Escherichia coli mutants with enhanced recombination between chromosomal duplications. J. Bacteriol. 130:167-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kow, Y. W. 2002. Repair of deaminated bases in DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33:886-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozmin, S. G., Y. I. Pavlov, R. L. Dunn, and R. M. Schaaper. 2000. Hypersensitivity of Escherichia coli Δ(uvrB-bio) mutants to 6-hydroxylaminopurine and other base analogs is due to a defect in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:3361-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozmin, S. G., R. M. Schaaper, P. V. Shcherbakova, V. N. Kulikov, V. N. Noskov, M. L. Guetsova, V. V. Alenin, I. B. Rogozin, K. S. Makarova, and Y. I. Pavlov. 1998. Multiple antimutagenesis mechanisms affect mutagenic activity and specificity of the base analog 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine in bacteria and yeast. Mutat. Res. 402:41-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krokan, H. E., F. Drablos, and G. Slupphaug. 2002. Uracil in DNA—occurrence, consequences and repair. Oncogene 21:8935-8948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuzminov, A. 2001. Single-strand interruptions in replicating chromosomes cause double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8241-8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leimkuhler, S., M. Kern, P. S. Solomon, A. G. McEwan, G. Schwarz, R. R. Mendel, and W. Klipp. 1998. Xanthine dehydrogenase from the phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus is more similar to its eukaryotic counterparts than to prokaryotic molybdenum enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 27:853-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin, S., A. G. McLennan, K. Ying, Z. Wang, S. Gu, H. Jin, C. Wu, W. Liu, Y. Yuan, R. Tang, Y. Xie, and Y. Mao. 2001. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a human inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase encoded by the ITPA gene. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18695-18701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Link, A. J., D. Phillips, and G. M. Church. 1997. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol. 179:6228-6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lusetti, S. L., and M. M. Cox. 2002. The bacterial RecA protein and the recombinational DNA repair of stalled replication forks. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:71-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahdi, A. A., and R. G. Lloyd. 1989. Identification of the recR locus of Escherichia coli K-12 and analysis of its role in recombination and DNA repair. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:503-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marians, K. J. 2000. PriA-directed replication fork restart in Escherichia coli. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marians, K. J. 2000. Replication and recombination intersect. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10:151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Nichols, B. P., O. Shafiq, and V. Meiners. 1998. Sequence analysis of Tn10 insertion sites in a collection of Escherichia coli strains used for genetic mapping and strain construction. J. Bacteriol. 180:6408-6411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noskov, V. N., K. Staak, P. V. Shcherbakova, S. G. Kozmin, K. Negishi, B. C. Ono, H. Hayatsu, and Y. I. Pavlov. 1996. HAM1, the gene controlling 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine sensitivity and mutagenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 12:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavlov, Y. I. 1986. Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants highly sensitive to the mutagenic action of 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine. Soviet Genet. 22:1099-1107. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavlov, Y. I., V. V. Suslov, P. V. Shcherbakova, T. A. Kunkel, A. Ono, A. Matsuda, and R. M. Schaaper. 1996. Base analog N-6-hydroxylaminopurine mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: genetic control and molecular specificity. Mutat. Res. 357:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radding, C. M. 1989. Helical RecA nucleoprotein filaments mediate homologous pairing and strand exchange. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1008:131-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajagopalan, K. V. 1996. Biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor, p. 674-679. In F. C. Neidhardt (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 47.Ronen, A. 1980. 2-Aminopurine. Mutat. Res. 75:1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 49.Sandler, S. J., and K. J. Marians. 2000. Role of PriA in replication fork reactivation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaaper, R. M. 1993. Base selection, proofreading, and mismatch repair during DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:23762-23765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro, R., and S. H. Pohl. 1968. The reaction of ribonucleosides with nitrous acid. Side products and kinetics. Biochemistry 7:448-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapiro, R., and S. J. Shiuey. 1969. Reaction of nitrous acid with alkylaminopurines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 174:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spek, E. J., L. N. Vuong, T. Matsuguchi, M. G. Marinus, and B. P. Engelward. 2002. Nitric oxide-induced homologous recombination in Escherichia coli is promoted by DNA glycosylases. J. Bacteriol. 184:3501-3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spek, E. J., T. L. Wright, M. S. Stitt, N. R. Taghizadeh, S. R. Tannenbaum, M. G. Marinus, and B. P. Engelward. 2001. Recombinational repair is critical for survival of Escherichia coli exposed to nitric oxide. J. Bacteriol. 183:131-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor, A. F., D. W. Schultz, A. S. Ponticelli, and G. R. Smith. 1985. RecBC enzyme nicking at Chi sites during DNA unwinding: location and orientation-dependence of the cutting. Cell 41:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wechsler, J. A., and J. D. Gross. 1971. Escherichia coli mutants temperature-sensitive for DNA synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 113:273-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss, B. 2001. Endonuclease V of Escherichia coli prevents mutations from nitrosative deamination during nitrate/nitrite respiration. Mutat. Res. 461:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao, M., Z. Hatahet, R. J. Melamede, and Y. W. Kow. 1994. Purification and characterization of a novel deoxyinosine-specific enzyme, deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease, from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16260-16268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao, M., and Y. W. Kow. 1997. Further characterization of Escherichia coli endonuclease V. Mechanism of recognition for deoxyinosine, deoxyuridine, and base mismatches in DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 272:30774-30779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao, M., and Y. W. Kow. 1995. Interaction of deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli with DNA containing deoxyinosine. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28609-28616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yao, M., and Y. W. Kow. 1994. Strand-specific cleavage of mismatch-containing DNA by deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31390-31396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zalkin, H., and P. Nygaard. 1996. Biosynthesis of purine nucleotides, p. 561-579. In F. C. Neidhardt (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 63.Zieg, J., V. F. Maples, and S. R. Kushner. 1978. Recombinant levels of Escherichia coli K-12 mutants deficient in various replication, recombination, or repair genes. J. Bacteriol. 134:958-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]