Abstract

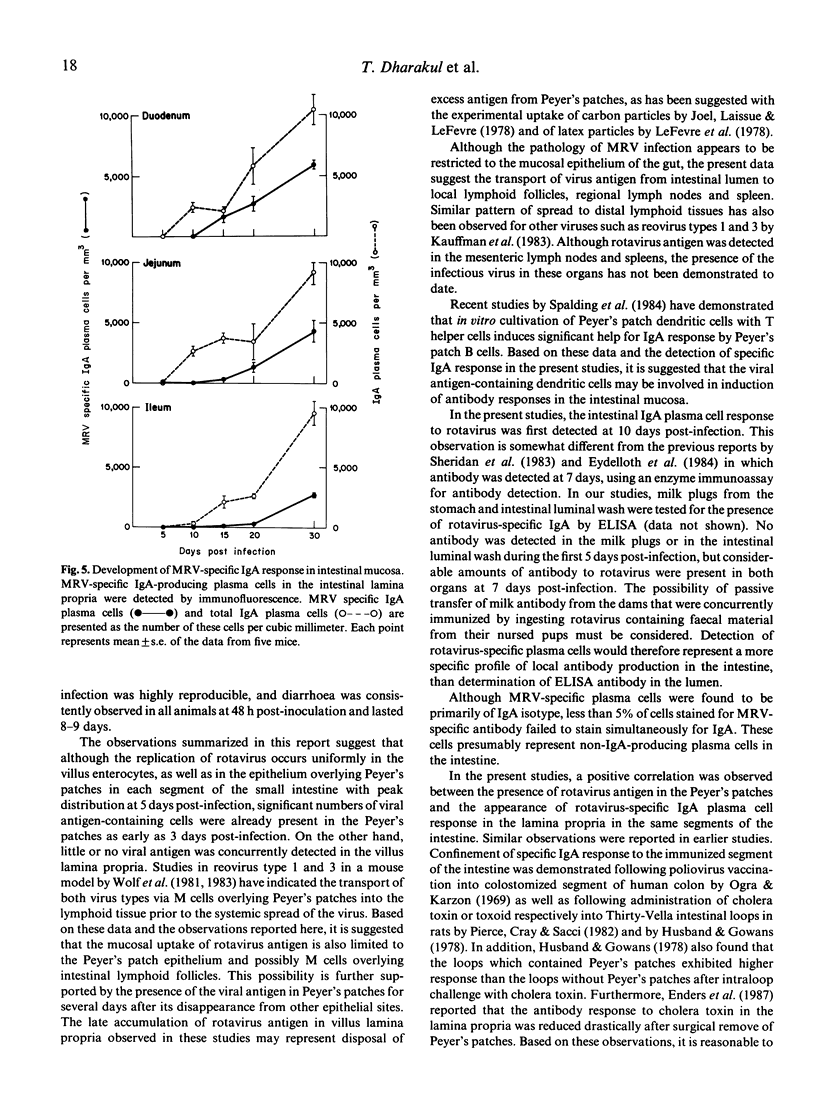

Groups of suckling BALB/c mice were inoculated with murine rotavirus (MRV) at 5 days of age and sequentially tested for the presence of MRV antigen (Ag) in intestinal villus epithelium (VE), Peyer's patch (PP), mesenteric lymph node (MLN), spleen, liver and lung, using indirect immunofluorescence techniques (IF). MRV Ag was first detected in VE 24 h after oral administration of the virus and remained in VE for as long as 10 days post-inoculation (pi). MRV Ag was observed in the epithelium overlying PP at 3-7 days pi and in subepithelial and interfollicular areas in the PP between 3 and 20 days pi. MRV Ag was also detected in MLN during the same period of time. Small numbers of MRV-Ag-containing cells were detected in the lamina propria (LP) of intestinal villi at 10 days pi. Most MRV-Ag-containing cells in PP and MLN were Ia-positive but negative for Lyt-1, Lyt-2 and MAC-1 cell surface markers. MRV-Ag-containing cells were negative for surface or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin. Intestinal antibody response to MRV indicated by the presence of MRV-specific IgA plasma cells in LP was first detectable 10 days pi. Highest density of MRV-specific plasma cells was observed in the duodenum, with a similar distribution to that of MRV-Ag-containing cells in PP. These observations suggest that MRV-Ag uptake is largely limited to the PP associated epithelium and the virus Ag is subsequently transported to the underlying lymphoid follicles and MLN. These findings suggest a close relationship between the availability of MRV Ag in the lymphoid follicles at different locations and the subsequent development of local antibody responses in different segments of small intestine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Black R. E., Merson M. H., Huq I., Alim A. R., Yunus M. Incidence and severity of rotavirus and Escherichia coli diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Implications for vaccine development. Lancet. 1981 Jan 17;1(8212):141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders G. A., Delius M., Ballhaus S., Brendel W. Role of Peyer's patch in the intestinal immune response to cholera toxin in enterically immunized rats. Infect Immun. 1987 Sep;55(9):1997–1999. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.1997-1999.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eydelloth R. S., Vonderfecht S. L., Sheridan J. F., Enders L. D., Yolken R. H. Kinetics of viral replication and local and systemic immune responses in experimental rotavirus infection. J Virol. 1984 Jun;50(3):947–950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.3.947-950.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husband A. J., Gowans J. L. The origin and antigen-dependent distribution of IgA-containing cells in the intestine. J Exp Med. 1978 Nov 1;148(5):1146–1160. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.5.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D. D., Laissue J. A., LeFevre M. E. Distribution and fate of ingested carbon particles in mice. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1978 Nov;24(5):477–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman R. S., Wolf J. L., Finberg R., Trier J. S., Fields B. N. The sigma 1 protein determines the extent of spread of reovirus from the gastrointestinal tract of mice. Virology. 1983 Jan 30;124(2):403–410. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre M. E., Olivo R., Vanderhoff J. W., Joel D. D. Accumulation of latex in Peyer's patches and its subsequent appearance in villi and mesenteric lymph nodes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1978 Nov;159(2):298–302. doi: 10.3181/00379727-159-40336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offit P. A., Clark H. F. Maternal antibody-mediated protection against gastroenteritis due to rotavirus in newborn mice is dependent on both serotype and titer of antibody. J Infect Dis. 1985 Dec;152(6):1152–1158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offor E., Riepenhoff-Talty M., Ogra P. L. Effect of malnutrition on rotavirus infection in suckling mice: kinetics of early infection. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1985 Jan;178(1):85–90. doi: 10.3181/00379727-178-41987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogra P. L., Karzon D. T. Distribution of poliovirus antibody in serum, nasopharynx and alimentary tract following segmental immunization of lower alimentary tract with poliovaccine. J Immunol. 1969 Jun;102(6):1423–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce N. F., Gowans J. L. Cellular kinetics of the intestinal immune response to cholera toxoid in rats. J Exp Med. 1975 Dec 1;142(6):1550–1563. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.6.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger S. M., Schnagl R. D., Holmes I. H. Biochemical and biophysical characteristics of diarrhea viruses of human and calf origin. J Virol. 1975 Nov;16(5):1229–1235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.5.1229-1235.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J. F., Eydelloth R. S., Vonderfecht S. L., Aurelian L. Virus-specific immunity in neonatal and adult mouse rotavirus infection. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):917–927. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.917-927.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass D. R., Wells P. W. Rotavirus infection in lambs: studies on passive protection. Arch Virol. 1976;52(3):201–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01348017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding D. M., Williamson S. I., McGhee J. R., Koopman W. J. Peyer's patch dendritic cells: isolation and functional comparison with murine spleen dendritic cells. Immunobiology. 1984 Dec;168(3-5):380–390. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(84)80124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urasawa T., Urasawa S., Taniguchi K. Sequential passages of human rotavirus in MA-104 cells. Microbiol Immunol. 1981;25(10):1025–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1981.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. L., Kauffman R. S., Finberg R., Dambrauskas R., Fields B. N., Trier J. S. Determinants of reovirus interaction with the intestinal M cells and absorptive cells of murine intestine. Gastroenterology. 1983 Aug;85(2):291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. L., Rubin D. H., Finberg R., Kauffman R. S., Sharpe A. H., Trier J. S., Fields B. N. Intestinal M cells: a pathway for entry of reovirus into the host. Science. 1981 Apr 24;212(4493):471–472. doi: 10.1126/science.6259737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zoysa I., Feachem R. G. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: rotavirus and cholera immunization. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(3):569–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]