Abstract

Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) was combined with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) to study the transition between acid-denatured states and the native structure of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The use of these techniques in concert proved to be more powerful than either alone, yielding a two-dimensional picture of the folding energy landscape of Cyt c. TCSPC measured the distribution of distances between the heme of the protein and a covalently attached dye molecule at residue C102 (one folding reaction coordinate), whereas FCS measured the hydrodynamic radius (a second folding reaction coordinate) of the protein over a range of pH values. These two independent measurements provide complimentary information regarding protein conformation. We see evidence for a well defined folding intermediate in the acid renaturation folding pathway of this protein reflected in the distribution of lifetimes needed to fit the TCSPC data. Moreover, FCS studies revealed this intermediate state to be in dynamic equilibrium with unfolded structures, with conformational fluctuations into and out of this intermediate state occurring on an ≈30-μs time scale.

Keywords: fluorescence correlation, maximum entropy, time-correlated single photon counting, protein folding

The folded state of most proteins is a compact and ordered structure, whereas the unfolded state (random coil) is usually significantly larger and substantially less ordered. The manner in which this myriad of random coil conformations folds into this collection of substantially more ordered sets of similar conformations (conformational substates) is still the subject of much research and debate. Fluorescence spectroscopies have seen widespread use in helping to elucidate these folding mechanisms, with examples ranging from investigation of the time scale of fluctuations in the unfolded protein ensemble (1) to single-molecule studies of individual protein folding trajectories (2) or the classification of the conformations of individual protein molecules (2–5).

FRET (6, 7) is a particularly useful method for studying the conformational state of biological molecules and has been widely used to study protein folding (2–5, 8). FRET involves the nonradiative transfer of energy from a fluorescence donor chromophore to a fluorescence acceptor, with the acceptor generally possessing a red-shifted emission and absorption spectrum from that of the donor. The energy transfer rate is inversely proportional to the separation distance between the molecules to the sixth power (6). Because of the strong dependence of energy transfer rate on separation distance, it can be used as a “spectroscopic ruler” (9) to measure donor–acceptor distances over the biologically relevant distance range of 20–80 Å.

Experimental methods for measuring energy transfer efficiency are reviewed elsewhere (7). One commonly used method is to choose an excitation wavelength that preferentially excites the donor molecule and measure the increased fluorescence emission of the acceptor molecule. This technique, however, only works in instances where the acceptor is fluorescent. An alternative means of measuring the transfer efficiency that works in cases where the acceptor molecule is not fluorescent is to measure the fluorescence lifetime of the donor molecule in the presence (τda) and absence (τd) of the acceptor molecule. Although this method is less commonly used, measuring changes in the fluorescence lifetime of the donor molecule confers distinct advantages over ratiometric measures of energy transfer efficiency. In particular, lifetime measurements can reveal heterogeneity in the distribution of donor–acceptor distances (8, 10, 11), and lifetime methods do not suffer from all of the correction factors needed by ratiometric measurements to turn measured parameters into an absolute energy transfer efficiency and thus an absolute distance measurement (7).

Although monitoring changes in a donor fluorescence lifetime provides a unique opportunity to explore and quantify sample heterogeneity, the distance probability distributions obtained from these analyses yield static pictures of conformational heterogeneity present in the sample and proffer little about the time scale of the conformational fluctuations that are ongoing in the population. One means of arriving at this dynamic information is, of course, to combine fluorescence lifetime methods with rapid mixing or perturbation methods (8).

An alternative method of looking at conformational dynamics in these systems is provided by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) (12–14). In FCS, the light emitted from a small confocal excitation volume element is detected, and the deviations of the light from the average level are autocorrelated. In solution measurements, the temporal decay of the autocorrelation function primarily reflects the translational diffusion time of the molecule across the excitation probe volume, although the decay can also reflect fluctuations in light intensity resulting from changes to the fluorophore’s emission rate during transit. These changes in emission rate can be due to crossing from the singlet state into a nonfluorescent triplet (15), changes in the chemical structure of the chromophore (16, 17), or conformational fluctuations of the molecule (1, 18). From the diffusional component of the measured autocorrelation curve, one can extract a hydrodynamic radius of the species under study by means of the Stokes–Einstein relation (14). In this fashion, FCS can measure the hydrodynamic radius or physical extension of a protein during its folding (19).

Here, we combine time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC), which measures a single discernable protein folding coordinate [the distance between a covalently attached fluorescent reporter and the heme of the protein investigated, cytochrome c (Cyt c)] with FCS, which measures changes in the overall physical dimensions of the protein. The combination of these techniques yields two independent and supporting measures of protein conformation. Additionally, FCS was used to measure conformational fluctuations in the protein population. This work found evidence for a well defined folding intermediate, with fluctuations into and out of this intermediate occurring on a ≈30-μs time scale.

Results

As is the case for Cyt c from this same organism labeled with a dansyl fluorophore (8), the fluorescence of tetramethyl rhodamine (TMR) is quenched in the folded state of the protein because of Förster energy transfer to the heme. Although the TMR emission lies significantly to the red of the Soret absorption of the heme (λmax ≈ 410 nm) and TMR–heme seems like an ill-chosen FRET pair, there is substantial overlap of the TMR emission with the lower energy Q bands. Using the standard Förster theory (6) approximations, we calculate from this overlap a Förster radius for the heme–TMR FRET pair of 40 Å.

Cyt c–TMR is fluorescent in the acid-denatured state and quenched in the folded state (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site); the fluorescence of TMR alone changes little (< 10%) over this pH range. The integral of the fluorescence counts can be used to construct an equilibrium denaturation curve.

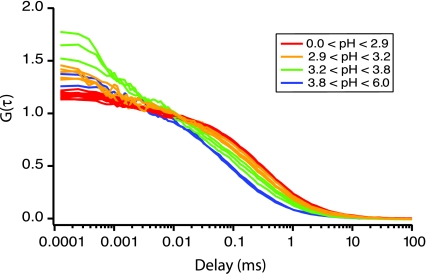

Twenty-two fluorescence correlation functions, measured for 19 discrete pH values spanning the folded and acid-denatured states of Cyt c–TMR, are shown in Fig. 1. Amplitudes of the correlation functions were ≈0.1, corresponding to ≈10 molecules in the optical probe volume. The correlation functions shown in Fig. 1 have been normalized (based on the number occupancy from fits to the data) and smoothed (five-point boxcar) to aid in visualization (smoothing was performed for visualization only; raw, weighted data are analyzed for the rest of this work). The protein correlations are displayed in a coarse rainbow color scale, with acid-denatured protein correlation functions colored red, intermediate pH values colored orange or green, and the folded protein correlation functions colored blue.

Fig. 1.

Normalized cross-correlation curves for Cyt c–TMR over a range of pH values. A coarse rainbow coloring scheme has been used. Acid-denatured proteins are colored red (pH < 2.9). From pH 2.9 to 3.2, the correlation curves are colored orange. From pH 3.2 to 3.8, the curves are colored green. Above pH 4.0, the correlation curves are colored blue. A five-point boxcar smooth has been applied to these data to aid visualization.

From the autocorrelation curves, one notices two primary effects as the protein begins to fold from an acid-denatured state to the native conformation. First, the average correlation time (τc) decreases as the protein becomes folded (curves progress inward to shorter correlation times with increasing pH). Second, there is a measurable fast decay component in the correlation function that manifests itself as the protein folds (most evident in the green autocorrelation curves seen for times <0.01 ms). Fits and residuals of four representative correlation functions are given in Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

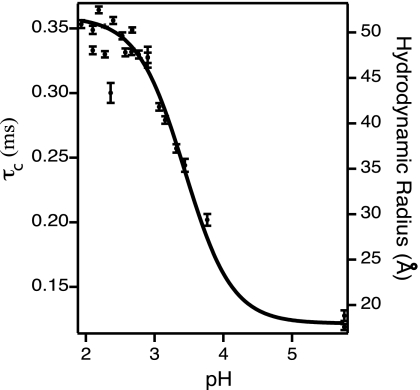

We have fit the measured correlation functions to the model described in Materials and Methods. Fig. 2 plots the diffusional correlation time determined from the fit vs. the pH of the Cyt c sample under investigation. The diffusional correlation time is directly proportional to the average hydrodynamic radius of TMR–Cyt c (14, 19). The right axis of Fig. 2 converts the measured diffusional correlation time to a hydrodynamic radius.

Fig. 2.

Equilibrium denaturation monitored by FCS. The diffusional correlation time vs. the sample pH is plotted on the left-hand axis. The right-hand axis converts this correlation time to a hydrodynamic radius. A sigmoidal fit to the data is overlaid.

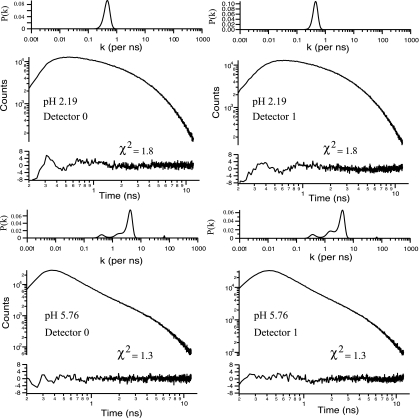

Coincident with the fluorescence correlation measurements, the fluorescence lifetime of the TMR-labeled Cyt c was measured by using TCSPC. Fig. 3 shows the fluorescence lifetime decay measured for two extreme pH values (pH = 2.19 and 5.76). Because two detectors were used to measure the cross-correlation functions, we have, in essence, two TCSPC decays for every point in the pH titration. We show both decays for these two pH values to enable the reader to get a “chi-by-eye” (20) feel for the uncertainty in the shape and character of the distributions returned by the maximum entropy fits to the data.

Fig. 3.

Representative fluorescence lifetime decays and maximum entropy fits and residuals. (Upper) The fluorescence lifetime decay, P(k) distribution, fit, and residual to TCSPC data for the acid-denatured protein (pH = 2.19). Because two channels were used in the fluorescence cross-correlation measurements, two lifetime decays were collected for each protein sample. (Lower) Same as above, but pH = 5.76. At pH 5.76, the protein is folded, and the TMR is quenched by means of Förster transfer to the heme.

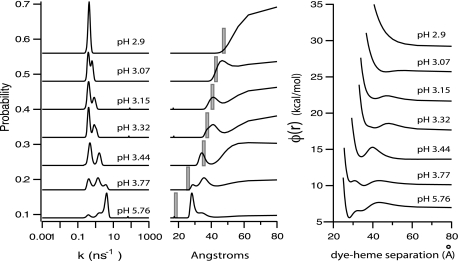

The P(k) distribution for the protein evolves steadily with alterations in pH (shown in Fig. 4Left). The P(k) distribution shown is the average of the P(k) distribution obtained in each correlated photon counting channel. The acid-denatured protein shows a single component in the P(k) distribution (k ≈ 0.45 ns−1; τ ≈ 2.2 ns), whereas above pH 3, a second component begins to emerge from the maximum entropy fits to the data (k ≈ 1.3 ns−1 or τ ≈ 770 ps). Above pH 3.5, a third, highly quenched component emerges (k ≈ 3.8 ns−1; τ ≈ 270 ps). We have assigned the peaks in the data as being due to the unfolded protein (k ≈ 0.45 ns−1), the folded protein (k ≈ 3.8 ns−1), and an intermediate structure (k ≈ 1.3 ns−1) (a compact intermediate state along the acid renaturation path) (21, 22).

Fig. 4.

Evolution of folding reaction coordinates and potential energy surfaces as a function of pH. (Left) The P(k) distribution determined by maximum entropy as a function of pH. (Center) Conversion of the P(k) distribution to a P(r) distribution. Overlaid (vertical bars) is the average hydrodynamic radius determined by FCS. (Right) The evolution of the potential energy surface for the dye–heme separation distance. These surfaces were made assuming that the middle P(r) distribution was governed by a potential of mean force.

The Fig. 4 Center shows the P(r) probability distribution of distances between the dye and the heme derived from the P(k) distribution. Although the breadth of the P(k) distribution derived from maximum entropy fits can be affected by many factors, such as measurement noise, the data suggest a broader distribution of dye–heme distances are sampled by the intermediate state than are sampled by the native structure of the protein. Overlaid in Fig. 4 Center with the P(r) distribution determined from the TCSPC data are the average hydrodynamic radii determined by FCS for these same pH values. Fig. 4 Right converts the distance probability distribution into a potential of mean force [i.e., P(r) = exp(−φ(r)/kBT)] (3).

The absolute values of the dye–heme separation distance and the hydrodynamic radius for the folded protein obtained in this study are ≈27 Å and ≈18 Å, respectively. The reported dye–heme distance in the folded form of Cyt c from the same organism is ≈26 Å (using dansyl as the FRET donor) (8), whereas the radius of gyration of Cyt c from horse heart determined by small angle x-ray scattering is ≈14 Å (22). We note that a hydrodynamic radius should be slightly larger than the radius of gyration determined in a small-angle x-ray scattering measurement. The hydrodynamic radius of a protein consists of the average size of the molecule plus any associated water molecules, whereas the radius of gyration is a mass-weighted mean-squared radial value.

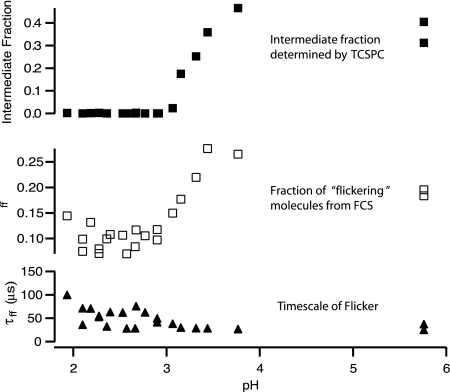

There is a good correlation between the population of molecules in the intermediate state determined by TCSPC and the fraction of molecules that are “flickering” determined by FCS (Fig. 5). The fraction in intermediate state determined by TCSPC is given by the sum of the probability distribution between 0.82 < k < 2.44, whereas the fraction of the molecules in the optical probe volume that are undergoing a flickering process is given by the ff parameter in the fits to FCS data. The fraction of molecules that are undergoing a flickering process tracks well with the fraction of molecules in the intermediate state determined by TCSPC. We have assigned the flickering process to changes in the protein conformation between the unfolded and intermediate states. These two states have different fluorescence lifetimes and thus different fluorescence quantum yields and different brightness; a fluctuation between these two states manifests itself as a decay component in the autocorrelation function. Moreover, the compaction of Cyt c to its first folding intermediate is known to occur on a 50-μs time scale (23). Fig. 5 Bottom shows the dependence of the flickering time on pH. The time scale of the flickering process is quite consistent with the time scale of the compaction of the unfolded protein to its intermediate state. Although the data in Fig. 5 Bottom are certainly noisy, the trend appears to be that the flickering rate increases with increasing pH. The values for the flickering time scale best determined (those that have the largest fraction in the flickering component: i.e., those near pH 3.5) yield a flickering time scale of ≈30 μs, and the straight linear average of all flickering times is ≈30 μs).

Fig. 5.

Correspondence of TCSPC and FCS data. (Top) Plot of the fraction of molecules in the intermediate state as determined by TCSPC. (Middle) Fraction of molecules that are flickering while crossing the probe volume. (Bottom) Time scale of this flicker. We attribute the fluorescence flicker to conformational fluctuations between the unfolded protein and a compact intermediate state (see Discussion for details).

Discussion

The distance between residue C102 and the heme of Cyt c is one potential protein folding reaction coordinate. Although it is perhaps not the most relevant reaction coordinate for following the folding of an ≈100-aa residue chain, it does have the benefit that this distance is easily measured experimentally. However, not only is the “average” distance between these sites easily measured, but one can begin to study the distribution of distances by using TCSPC methods, as was done herein and reported previously (8, 10, 11). If one assumes that this distance distribution is governed by a potential of mean force (Fig. 4 Right), then what emerges from the data is a one-dimensional slice of the highly dimensional folding free-energy landscape (24, 25).

Another “slice” of this landscape, or reaction coordinate for the polypeptide collapse and folding, is the hydrodynamic radius of the molecule provided by FCS. By comparing the changes in hydrodynamic radius as a function of pH to the changes in dye–heme distance of Fig. 4, one can infer that the curvature of the landscape between pH 3.44 and pH 5.76 must be greater along the hydrodynamic radius coordinate than it is in the dye–heme coordinate in this pH range. Moreover, although it is noisy, the dependence of the flickering time scale with pH (Fig. 5) suggests that faster conformational fluctuations (lower barriers between the unfolded and intermediate states) are sampled closer to the folding transition.

These different insights of the folding landscape are best understood in the context of protein structure. The TMR donor is on the C terminus of the protein (C102), near the end of the C-terminal helix. The heme acceptor is covalently attached to the protein at Cys-14 and Cys-17, at the turn just after the N-terminal helix. Thus, the donor and acceptor chromophores are separated by 85 residues. In the unfolded state, a broad distribution of donor–acceptor distances is possible; an average distance >50 Å is reasonable for a random coil. The intermediate state has been characterized by CD spectroscopy and is known to have a substantial population of α-helices (21). The three major helices all exhibit substantial protection of the amide protons from H/D exchange in the intermediate state (21), suggesting significant helix–helix stabilizing interactions. At low pH (<5) misligation of H33 to the heme is suppressed by protonation of this nonnative ligand. Therefore, the compact intermediate observed in these measurements most likely has the native H18 ligation.

Ligation of H18, combined with stabilizing interactions between the N- and C-terminal helices, serves to bring the TMR donor and heme acceptor chromophores into a near native-like interaction distance. Formation of the compact intermediate structure occurs between pH 2.9 and 3.8 (Fig. 4 Center), bringing the donor and acceptor to a well defined separation. In contrast, the hydrodynamic radius of the protein is still far from the native value under these conditions. It is likely that the large loop between the N-terminal helix and the 60s helix remains disordered at low pH and only attains its native configuration near a pH of ≈6. Disorder of this loop is likely the origin of the large hydrodynamic radius under conditions where dye–heme separation is nearly native. We infer that the initial collapse of the polypeptide chain forms a compact intermediate structure with a native-like orientation of the two ends of the protein, but this structure possesses a substantially disordered region in between.

In addition to the two-dimensional static view of the folding energy landscape presented by simultaneous FCS and TCSPC measurements, this work reinforces the fact that fluorescence fluctuation measurements can arrive at kinetic and dynamic information (1, 18) without the need to perturb the populational equilibrium, as is done in relaxation measurements of protein dynamics. Here, we assign a fast flickering component detected in the autocorrelation functions of this protein to transitions between the unfolded protein ensemble and a compact intermediate state. This assignment is supported strongly by two independent facts. First, the time scale of the fluctuation (≈30 μs) agrees well with the time scale of the compaction of the protein to the intermediate state as studied by Trp fluorescence (23) and is far removed from the triplet lifetime of the fluorophore (≈2 μs). Second, the fraction of molecules that appear to be flickering during their transit through the probe volume matches well with the fraction of molecules in the intermediate state as determined by TCSPC (Fig. 5). The correspondence of the flickering population determined with FCS with the intermediate population determined by TCSPC demonstrates the power provided by the combination of these techniques: One can map specific conformational fluctuation time scales with certain known protein subpopulations.

The combination of TCSPC and FCS to study the acid renaturation path of Cyt c enables a two-dimensional view of the folding energy landscape for this protein. One can simultaneously extract a specific conformational coordinate (dye–heme distance, by means of TCSPC) as well as measure the overall physical dimensions of the proteins (by means of FCS). Moreover, fluctuations in the fluorescence light intensity revealed that the unfolded state ensemble is in dynamic equilibrium with a compact intermediate structure and that transitions between these two states occur on a 30-μs time scale. Thus, with the combination of FCS and TCSPC, not only is a two-dimensional static view of the energy landscape of this protein accessible, but one can directly learn about the time scale of the conformational dynamics of proteins that reside on that landscape.

Materials and Methods

Protein Labeling and Purification.

Cyt c from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. TMR iodoacetamide was purchased from Molecular Probes and attached to the one free cysteine (C102) of this protein by using the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Extensive dialysis (≈48 h) under denaturing conditions was used to separate free TMR from the TMR reporter covalently attached to Cyt c. The labeling efficiency was estimated at 40%, based on UV-visible absorption measurements of the protein–TMR complex.

Bulk Fluorimetry.

An ≈100 nM solution of Cyt c–TMR was placed in a cuvette in a fluorolog fluorometer (Spex Industries, Metuchen, NJ). Excitation was at 530 nm, and emission was monitored between 550 and 650 nm. These measurements were performed over a range of pH values that spanned the transition from folded to acid-denatured structure. The pH was buffered at each pH value by using a mixture of mono- and dibasic sodium phosphate.

FCS and Lifetime Measurements.

FCS and TCSPC were performed on a home-built confocal microscope (described in ref. 4). A small fraction (200 μW) of the 514-nm light emitted from a mode-locked argon ion laser (Model 2080, Spectra-Physics; 82-MHz pulse repetition rate and ≈100-ps pulse width) was reflected by a dichroic mirror (525-nm long-pass; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) into the back of the microscope objective (×100, 1.2-numerical aperture Leitz water immersion) and focused to a near-diffraction limited spot in the sample droplet ≈25 μm away from the solvent–glass interface. The fluorescence emitted from the probe volume was collected by the objective, passed through the excitation dichroic, and spatially filtered (with a 100-μm pinhole) before being split by a 50/50 beamsplitter (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) onto two avalanche photodiodes (SPCM 200 PQ; PerkinElmer). Each emission arm of the microscope had independent spectral filters. Arm 1 used a 50-nm band-pass filter centered at 580 nm; arm 2 used a 30-nm band-pass filter centered at 575 nm (Omega Optical).

The output pulses from the detectors were suitably conditioned before being fed into a constant fraction discriminator (CFD) (TC454 quad; Tennelec, Oak Ridge, TN). For each detector, one NIM output of the CFD was conditioned and fed into the input of a digital correlator card (ALV-5000E; ALV-Laser Vertriebsgesellschaft, Langen/Hessen, Germany); another output of the CFD was conditioned and fed into a TCSPC card (SPC-630; Becker & Hickl, Berlin). Fluorescence lifetime decays were acquired in 1,024 channels with 16.276 ps per channel.

Normalized cross-correlations [Gx(τ)] of the detector counts were performed by using the supplied ALV-5000 hardware/software. Cross-correlation, rather than single detector autocorrelation, was used to eliminate the effects of detector dead time and after-pulsing.

Fitting Procedures.

The expected correlation function due to the diffusion of molecules into and out of a two-dimensional Gaussian probe volume was treated by the method described by Elson and Magde (12). We have fit the measured correlation functions to this model and have accounted for triplet or dark-state transitions by the method of Widengren et al. (15). The following functional form was used to fit the measured data:

|

The six parameters in this expression are as follows: N is the average number of molecules in the probe volume, τc is the correlation time due to translation diffusion, ƒ is the fraction of irradiated molecules in the triplet state, τtr is the triplet lifetime, ff is the fraction of the molecules that are undergoing a fluorescence flicker (i.e., a change in the emission rate), τff is the time scale of the flickering process, and dc is a constant offset. The fits to the correlation functions were weighted by using error estimates based on the method of Koppel (26). As noted previously (27), this error estimation often leads to χ2 fit statistics <1. Based on the χ2 fit statistic and the shape of the residual, a two-dimensional approximation to the optical probe volume was deemed adequate to fit the FCS data while requiring one less fit coefficient than a three-dimensional model. The same criteria (χ2 fit statistic and the shape of the residual) were used to determine that two flickering components were needed to fit the autocorrelation data (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We emphasize that the observed second flickering process (≈30 μs) is well separated in time from the triplet lifetime (≈2.0 μs). The fits to the protein correlation functions varied five parameters; the dc offset was determined from the autocorrelation values at long delay times (>50 ms), and the triplet lifetime of the TMR label was held fixed at 2.0 μs. This value was chosen based on fits of the free TMR dye correlation functions (which have no second flickering process). If the triplet lifetime is allowed to vary freely in the Cyt c–TMR correlation functions, the values obtained were found to lie between 1 and 2.5 μs, with no discernable trends of this lifetime with pH. Fixing this value eliminated one more variable from the fit function.

Maximum Entropy Fitting of Lifetime Decays.

For a distribution of decay processes from the excited state of the fluorophore to its ground state, the observed fluorescence intensity after an infinitely short excitation pulse is given by

|

One desires to extract the P(k) distribution from the observed data I(t). When there is no a priori information as to the nature and shape of the P(k) distribution, maximum entropy methods provide a means of finding a P(k) distribution that imposes no structure on the distribution that is not dictated by the data (8, 28–30). Maximum entropy minimizes the reduced χ2 to a certain value, subject to the constraint that while the reduced χ2 statistic is minimized, the informational entropy of the P(k) distribution [the Jaynes entropy (31)] is maximized. For a “family” of P(k) distributions that has each ki weighted by an amplitude pi and that all fit the data equally well (based on the χ2 value), one chooses the P(k) distribution that maximizes the entropy of the distribution defined by

We have extracted the P(k) maximum entropy distributions from our TCSPC data by using Fortran code written by Lambright et al. (30) that finds the maximum entropy solution by means of the method of Skilling and Bryan (29). A family of 256 k values, logarithmically spaced between k = 0.001/ns and 1,000/ns, was chosen for the P(k) distribution. The initial distribution fed into the minimization procedure weighted each k equally. We varied the value of the target-reduced χ2 for each decay curve based on fits of that decay to discrete (one-, two-, or three-component) exponentials convolved with a Gaussian instrument response function. We used a visual inspection of the fit residual to determine the minimum number of components needed to adequately fit the data. The value of χ2 from this fit was used as the target-reduced χ2 value for the maximum entropy fitting software.

The P(k) distribution can be easily converted into a P(r) distribution (10), as in a Förster energy transfer mechanism; the transfer rate is given by

R0 is the Förster radius (the distance at which the transfer rate equals the fluorescence decay rate in the absence of transfer), and τf is the fluorescence lifetime of the donor fluorophore in the absence of the acceptor. This latter value was determined to be 2.2 ns (the fluorescence lifetime of free TMR dye measured in our TCSPC apparatus).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy Shreve and Mac Brown for helpful discussions concerning maximum entropy methods and Dick Keller for valuable technical discussions and a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Los Alamos National Laboratory and National Institutes of Health Grant GM53640.

Abbreviations

- TCSPC

time-correlated single photon counting

- TMR

tetramethyl rhodamine

- Cyt

c, cytochrome c

- FCS

fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Chattopadhyay K., Elson E. L., Frieden C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2385–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhoades E., Gussakovsky E., Haran G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3197–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628068100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talaga D., Lau W., Roder H., Tang J., Jia Y., Degrado W., Hochstrasser R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:13021–13026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mccarney E. R., Werner J. H., Bernstein S. L., Ruczinski I., Makarov D. E., Goodwin P. M., Plaxco K. W. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuler B., Lipman E., Eaton W. Nature. 2002;419:743–747. doi: 10.1038/nature01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster T. Ann. Phys. (Leipzig) 1948;2:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clegg R. M. Methods Enzymol. 1992;211:353–388. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)11020-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyubovitsky J., Gray H., Winkler J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:5481–5485. doi: 10.1021/ja017399r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stryer L., Haugland R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1967;58:719–726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas E., Wilchek M., Katchalski-Katzir E., Steinberg I. Z. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:1807–1811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navon A., Ittah V., Landsman P., Scheraga H., Haas E. Biochemistry. 2001;40:105–118. doi: 10.1021/bi001946o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elson E. L., Magde D. Biopolymers. 1974;13:1–27. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magde D., Elson E. L., Webb W. W. Biopolymers. 1974;13:29–61. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwille P., Bieschke J., Oehlenschlager F. Biophys. Chem. 1997;66:211–228. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(97)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widengren J., Mets U., Rigler R. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:13368–13379. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haupts U., Maiti S., Schwille P., Webb W. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:13573–13578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotlet M., Goodwin P. M., Waldo G. S., Werner J. H. ChemPhysChem. 2006;7:250–260. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnet G., Krichevsky O., Libchaber A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8602–8606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chattopadhyay K., Saffarian S., Elson E. L., Frieden C. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1413–1422. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Press W. H., Teukolsky S. A., Vetterling W. T., Flannery B. P. Numerical Recipes in C. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shastry M., Sauder J., Roder H. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:717–725. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akiyama S., Takahashi S., Kimura T., Ishimori K., Morishima I., Nishikawa Y., Fujisawa T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1329–1334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012458999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shastry M., Roder H. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:385–392. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dill K., Chan H. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:10–19. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frauenfelder H., Sligar S. G., Wolynes P. G. Science. 1991;254:1598–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1749933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koppel D. E. Phys. Rev. A. 1974;10:1938–1945. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wohland T., Rigler R., Vogel H. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2987–2999. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinbach P. J., Chu K., Frauenfelder H., Johnson J. B., Lamb D. C., Nienhaus G. U., Sauke T. B., Young R. D. Biophys. J. 1992;61:235–245. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skilling J., Bryan R. K. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1984;211:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambright D. G., Balasubramanian S., Boxer S. G. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10116–10124. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaynes E. T. Phys. Rev. 1957;106:620–630. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.