Abstract

We have studied the urea-induced unfolding of the E colicin immunity protein Im9 using diffusion single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Detailed examination of the proximity ratio of the native and denatured molecules over a wide range of urea concentrations suggests that the conformational properties of both species are denaturant-dependent. Whereas native molecules become gradually more expanded as urea concentration increases, denatured molecules show a dramatic dependence of the relationship between proximity ratio and denaturant concentration, consistent with substantial compaction of the denatured ensemble at low denaturant concentrations. Analysis of the widths of the proximity ratio distributions for each state suggests that whereas the native state ensemble is relatively narrow and homogeneous, the denatured state may possess heterogeneity in mildly denaturing conditions.

Heterogeneity occurs at the molecular scale throughout nature. The importance of understanding its effects is exemplified by the protein folding problem (1). An important objective in attempts to elucidate the mechanism of protein folding is to fully characterize all of the species populated along the folding trajectory, from the denatured to the native state ensemble, including any rarely populated states. The conformational properties of the denatured state have only recently begun to be elucidated through ensemble techniques such as NMR and SAXS (2). Results have demonstrated that residual interactions persist in the denatured state, which, in some cases, may even be native-like (2). However, the parameters obtained by these techniques are weight-averaged and hence the conformational heterogeneity of these states cannot be assessed. In principle, single molecule fluorescence represents a powerful method by which to both identify and characterize these ensembles. Excitingly, several such studies on proteins have recently shown the ability of these approaches to determine the properties of denatured molecules under conditions in which they are copopulated with the native state (3-7).

Here we describe single pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer (spFRET) measurements of the small single domain protein, Im9. The results reveal that the conformational properties of both the native and denatured ensembles depend critically on the denaturant concentration and suggest significant compaction of the denatured ensemble in low concentrations of urea.

Im9 is an 86-residue, four-helical protein that has been intensively investigated as a model for the folding of helical proteins and the thermodynamic and kinetic properties are well known: Im9 folds via a two-state mechanism at neutral pH, reaching the native state by a mechanism involving transient formation of a high-energy three-helical species (8). Little is known, however, about the structural properties of the denatured state or how residual interactions within this state influence the folding mechanism. For this study, a hexa-histidine-tagged version of the protein (Im9*) was created in which the single naturally occurring cysteine (C23) was retained while a second Cys was introduced (S81C). The protein was labeled specifically with Alexa 594 (at C23) and Alexa 488 (at C81) (see Supplementary Material). To confirm that a native-like fold was retained, tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of the protein in 0 and 8 M urea in buffer A (50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.01% (w/v) Tween 20 and 0.3 M sodium sulfate, pH 7.0) were obtained (Fig. 1, inset, left).

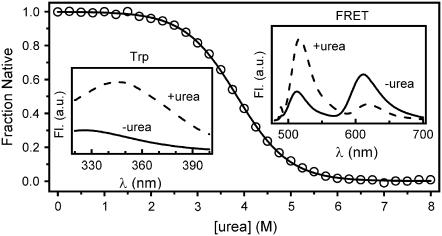

FIGURE 1 .

Urea-induced unfolding of double-labeled Im9*S81C monitored by ensemble FRET (main panel, circles). The solid line is a fit of the data to a two-state model. Tryptophan fluorescence (inset, left) and FRET spectra (inset, right) of double-labeled Im9*S81C in the presence of 8 M urea (+urea, dashed line) and in the absence of urea (−urea, solid line). All experiments performed in buffer A at 10°C.

The low Trp fluorescence intensity in the absence of urea is characteristic of the native state of Im9, the fluorescence of the single Trp being quenched by a specific His-Trp interaction (see Supplementary Material) (9). By contrast, the signal is enhanced in 8 M urea, consistent with denaturation of the protein. Further, one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra of native unlabeled and double labeled (DL) Im9*S81C were similar (data not shown).

The cooperativity and stability of DL Im9*S81C was investigated using ensemble FRET measurements (Fig. 1). As expected, a high FRET efficiency is observed for native DL Im9*S81C, consistent with the relatively close proximity of the dyes. In the presence of 8 M urea, the FRET efficiency is reduced as the protein is denatured (Fig. 1, inset, right). Using the ensemble-determined proximity ratio, a urea equilibrium denaturation curve was produced and the data fitted to a cooperative two-state transition model with ΔGUN = 16.1 ± 0.4 kJ·mol−1 and MUN = 4.2 ± 0.1 kJ·mol−1·M−1 (see Supplementary Material). The resulting MUN value for DL Im9*S81C is similar to that of wild-type Im9* under similar conditions (8,9), consistent with DL Im9*S81C adopting a native-like fold.

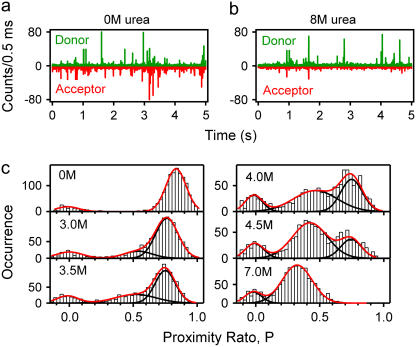

Single-molecule experiments of DL Im9*S81C were performed using a custom-built confocal microscope (see Supplementary Material). Data were collected by observing the transient bursts of fluorescence from DL Im9*S81C using an integration time of 0.5 ms as the individual molecules diffuse into and out of the <0.1 fl observation volume. Typical data are shown in Fig. 2, a and b.

FIGURE 2 .

Burst trajectories for the diffusion of DL Im9*S81C through the detection volume under (a) native and (b) denaturing conditions. (c) Representative proximity ratio histograms in different denaturant concentrations. Black lines are Gaussian fits to each species. Red lines are the sum of the individual Gaussian fits. All in buffer A, 10°C.

Under native conditions, many correlated donor and acceptor bursts are observed, indicating efficient FRET. By contrast, under denaturing conditions, less acceptor fluorescence is observed.

Using these data, histograms of the FRET proximity ratio (P = IA/[IA + ID], where IA and ID are the corrected donor and acceptor signals, respectively, in each integration time) for each single-molecule event over a defined threshold were calculated (see Supplementary Material). The resulting histogram in the absence of urea (Fig. 2 c; top left) reveals two main distributions: one with a high proximity ratio (∼0.8), which we assign to the native species, and a second at very low proximity ratio (∼0) assigned to molecules that lack an active acceptor (10). At high concentrations of denaturant (7 M; Fig. 2 c, bottom right) a third distribution at a proximity ratio of ∼0.3 is observed, suggesting less efficient energy transfer in denatured molecules. At intermediate urea concentrations, both populations of molecules coexist and no new distribution is resolved, consistent with two-state unfolding for this variant, as previously observed for the wild-type protein using ensemble methods (11).

The modal value, area, and width of each distribution can be analyzed to reveal how the distance between dye pairs, the relative population, and the configurational heterogeneity/dynamics change for each species as a function of denaturant concentration (6). To extract such data, the proximity ratio histograms throughout the urea titration were fitted to the sum of up to three Gaussians, with the areas of the Gaussians assigned to the native and denatured species, constrained to reflect the population of each species determined using ensemble denaturation experiments (see Supplementary Material). The resulting data are shown in Fig. 3.

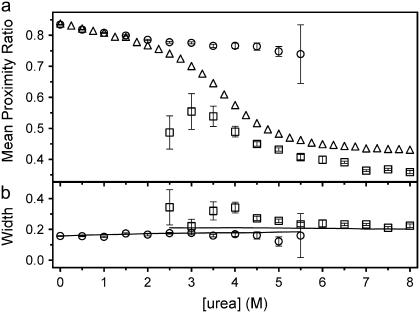

FIGURE 3 .

Parameters from Gaussian fits to the histograms shown in Fig. 2 c. (a) Mean proximity ratios of the native (○) and denatured (□) states of DL Im9*S81C. Also shown is the ensemble determined proximity ratio (▵, offset vertically by +0.25 to account for systematic differences in values obtained by single-molecule and ensemble techniques). (b) Width of the distributions of native and denatured molecules. Solid lines are the calculated expected peak widths of these distributions, assuming that only shot noise contributes to the width (see Supplementary Material). Error bars are ±1 SD.

The data reveal that the concentration of denaturant not only affects the equilibrium point but also significantly affects the average scalar separation between the dye pairs in the native and denatured states.

The slope of the mean proximity ratio of native molecules versus urea concentration shows a significant negative gradient, suggesting that the native molecules expand gradually as the concentration of the chaotrope is increased (this is not due to changes in the refractive index, dye orientation, quantum yield, or spectral overlap integral induced by the denaturant alone; see Supplementary Material). Such behavior has not been observed hitherto for other proteins examined by similar methods (3–6), presumably because the interdye separation in DL Im9*S81C renders this molecule particularly sensitive to small changes in protein dimensions in the native state (the dye attachment sites are ∼25 Å apart). Further, other DL Im9* constructs we have studied, with the same dye pair, but with higher initial native state proximity ratio, do not show the same marked dependence of the proximity ratio on the denaturant concentration (data not shown). The structural origin of this effect remains to be resolved.

The mean proximity ratio of denatured molecules for DL Im9*S81C shows a dramatic dependence on the concentration of urea, suggesting significant compaction of the denatured molecules as the concentration of urea is decreased. Similar observations have been obtained for other proteins using guanidium chloride as the chaotrope (3–7). The results obtained are thus consistent with a model, whereby the denatured polypeptide chain expands upon addition of chaotrope up to a level where chaotrope binding sites are saturated (Fig. 3 a) (12).

The width of the proximity ratio distribution for a discrete, static species is dominated by instrumental shot noise broadening (3). However, conformational heterogeneity or reconfiguration between subpopulations within each species may broaden these distributions beyond that predicted by shot noise effects. Comparison of the width of the distribution of native molecules of DL Im9*S81C with that calculated, assuming only shot noise contributions (and normalized to the width of the native ensemble in 0 M urea; see Supplementary Material) suggests a narrow and homogeneous ensemble of molecules within the native state at all denaturant concentrations (Fig. 3 b). By contrast, the width of the distribution of molecules corresponding to denatured DL Im9*S81C shows a clear deviation from the width predicted on the basis of only shot noise, particularly in mildly denaturing conditions. Together with the dependence of the proximity ratio on urea concentration, these data suggest changes in the rate of chain reconfiguration or the presence of static heterogeneity within the denatured ensemble that are critically dependent on the concentration of urea. Temporal measurements on immobilized single molecules have the potential to directly examine the nature of this heterogeneity and have shown for RNase H that subconformations may persist for up to 2 s (4). Such experiments, along with further diffusion experiments to attempt to dissect the heterogeneity in denatured protein proximity ratio distributions, are now under way for DL Im9* and its close homolog, Im7*.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Schuler, Stuart Warriner, Graham Spence, Sara Pugh, Jennifer Clark, and Claire Friel for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the University of Leeds. D.J.B. is an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council-funded White Rose Doctoral Training Centre lecturer and S.E.R. is a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council professorial fellow.

Tomoko Tezuka-Kawakami and Chris Gel contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Dill, K. A., and H. S. Chan. 1997. From Levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarney, E. R., J. E. Kohn, and K. W. Plaxco. 2005. Is there or isn't there? The case for (and against) residual structure in chemically denatured proteins. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deniz, A. A., T. A. Laurence, G. S. Beligere, M. Dahan, A. B. Martin, D. S. Chemla, P. E. Dawson, P. G. Schultz, and S. Weiss. 2000. Single-molecule protein folding: diffusion fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies of the denaturation of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:5179–5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzmenkina, E. V., C. D. Heyes, and G. U. Nienhaus. 2005. Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer study of protein dynamics under denaturing conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:15471–15476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzmenkina, E. V., C. D. Heyes, and G. U. Nienhaus. 2006. Single-molecule FRET study of denaturant induced unfolding of RNase H. J. Mol. Biol. 357:313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuler, B., E. A. Lipman, and W. A. Eaton. 2002. Probing the free-energy surface for protein folding with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nature. 419:743–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurence, T. A., X. Kong, M. Jäger, and S. Weiss. 2005. Probing structural heterogeneities and fluctuations of nucleic acids and denatured proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:17348–17353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friel, C. T., G. S. Beddard, and S. E. Radford. 2004. Switching two-state to three-state kinetics in the helical protein Im9 via the optimisation of stabilising non-native interactions by design. J. Mol. Biol. 342:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorski, S. A., A. P. Capaldi, C. Kleanthous, and S. E. Radford. 2001. Acidic conditions stabilise intermediates populated during the folding of Im7 and Im9. J. Mol. Biol. 312:849–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapanidis, A. N., T. A. Laurence, N. K. Lee, E. Margeat, X. Kong, and S. Weiss. 2005. Alternating-laser excitation of single molecules. Accounts Chem. Res. 38:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson, N., A. P. Capaldi, R. James, C. Kleanthous, and S. E. Radford. 1999. Rapid folding with and without populated intermediates in the homologous four-helix proteins Im7 and Im9. J. Mol. Biol. 286:1597–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso, D. O. V., and K. A. Dill. 1991. Solvent denaturation and stabilization of globular-proteins. Biochemistry. 30:5974–5985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]