Abstract

A novel group of retroviruses found within the order Crocodylia are described. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrate that they are probably the most divergent members of the Retroviridae described to date; even the most conserved regions of Pol show an average of only 23% amino acid identity when compared to other retroviruses.

The Retroviridae are a family of selfish genetic elements with a host range restricted to vertebrates (2, 5-7, 9, 22). They are currently subdivided into seven genera, all but one of which are harbored by mammalian or avian hosts (8, 11, 20, 21). There are currently no full-length retroviral sequences recovered from amphibians or reptiles, but analysis of PCR-amplified fragments from both vertebrate classes indicates that they harbor many elements that are only distantly related to other retroviruses (9, 18, 19).

We have previously described a large number of novel retroviruses via PCR amplification of approximately 1kb of the pol gene, followed by phylogenetic analysis (9, 14). During these studies, we characterized eight very unusual retroelements recovered from the order Crocodylia. The elements were present in all three extant families (the Alligatoridae, Crocodylidae, and Gavialidae (Table 1), and it is likely that similar elements remain to be found in many of the remaining 14 species constituting the order Crocodylia (1).

TABLE 1.

Host species used in this study

| Family and species | Common name | Retroviral product |

|---|---|---|

| Alligatoridae | ||

| Alligator sinensis | Chinese alligator | RV Chinese alligator I + II |

| Paleosuchus palpebrosus | Smooth-fronted caiman | RV smooth-fronted caiman |

| Caiman latirostris | Broad-nosed caiman | RV broad-nosed caiman |

| Crocodylidae | ||

| Crocodylus niloticus | Nile crocodile | RV Nile crocodile with CnEVI-III |

| Crocodylus intermedius | Orinoco crocodile | RV Orinoco crocodile |

| Gavialidae | ||

| Gavialis gangeticus | Gharial | Gharial II |

All eight elements were found to encode at least one in-frame stop codon or frameshift mutation, indicating they were endogenous in origin. We were unable to detect related elements in other organisms, either by PCR screening of other vertebrate taxa or by low-stringency hybridization of genomic DNA obtained from several birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. It is therefore likely that related elements are not widespread within vertebrate genomes.

To characterize these elements further, we constructed a genomic DNA library from liver tissue derived from a captive Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus). Genomic DNA was digested with Sau3A and 10- to 15-kb fragments were ligated into BamHI-digested lambda EMBL3, packaged, and plated. Nine plaque-purified positive clones were identified; three, termed CnEVI to -III, were fully sequenced.

Open reading frame (ORF) maps of CnEVI to -III revealed that each carried multiple in-frame stop codons and frameshift mutations. Analysis of a consensus sequence constructed from all three elements indicated that their original genomic organization probably consisted of two large ORFs, corresponding to the major retroviral genes gag and pol, and a small third ORF immediately upstream of the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR).

CnEVI contains a 593-bp 5′ LTR and a 585-bp 3′ LTR which differ from each other by approximately 7%, indicating that integration occurred some time ago. We were unable to unambiguously identify promoter or polyadenylation signals, but a putative polypurine tract and primer binding site were identified adjacent to the 3′ and 5′ LTRs, respectively. The primer binding site showed 14 of 18 matches to human tRNA (Ser).

The CnEVI Gag polyprotein is 526 residues in length and contains a consensus myristylation sequence (Met-Gly-X3-Ser) (21). No other obvious homology was observed with other retroviral Gag polyproteins. In particular, we were unable to identify either a Cys-His box or a major homology region (21). Translation of Pol requires a −1 ribosomal frameshift and, as seen with other retroviruses, we identified a slippery sequence together with an associated hairpin loop and pseudoknot immediately upstream of the 3′ end of gag (3, 4, 15). The predicted Pol polyprotein is 998 residues in length, with a gene order of protease, reverse transcriptase (RT), RnaseH, and integrase (Int). An additional ORF is located 3′ of pol, although BLAST searches of its translated product failed to reveal any similarity with other proteins. There was no evidence of an env gene, as is the case with some other members of the Retroviridae (10, 13, 17).

Table 2 shows the average percentage of amino acid identities between CnEVI to -III and the corresponding region (RT domains 1 to 7 [22]) from other retroelements. Sequence identity varied from 20% (human immunodeficiency virus type I) to 27% (human spumavirus [HSV]) with members of the Retroviridae and 18 to 24% with the gypsy-type LTR retrotransposons. This unusually low level of sequence identity is underscored by comparing both HSV and gypsy to the same retroviral isolates. HSV, one of the most divergent retroviruses described to date, shows a higher level of identity than CnEVI to -III in every comparison, and this is also generally the case for gypsy itself (which is not even a member of the Retroviridae).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of similarity between CnEVI to -III, prototypical members of the Retroviridae, and LTR retrotransposonsa

| % Similarity | % Similarity

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MuLV | HSV | MMTV | MPMV | BLV | RSV | HIV-1 | WDSV | gypsy | Del | RT412 | copia | Ty1 | Tnt1 | |

| CnEVI to -III | 22 | 27 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 23 | 24 | 18 | 20 | 13 | 14 | 10 |

| HSV | 38 | 29 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 32 | 30 | 24 | 28 | 15 | 16 | 10 | |

| gypsy | 28 | 30 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 28 | 25 | 26 | 33 | 42 | 16 | 17 | 13 | |

Calculated from amino acid alignment of RT domains 1 to 7, inclusive. Values are based on the calculation of average similarities observed for CnEVI to -III. MuLV, murine leukemia virus; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; MPMV, Mason-Pfizer monkey virus; BLV, bovine leukemia virus; RSV, Rous sarcoma virus; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; WDSV, walleye dermal sarcoma virus.

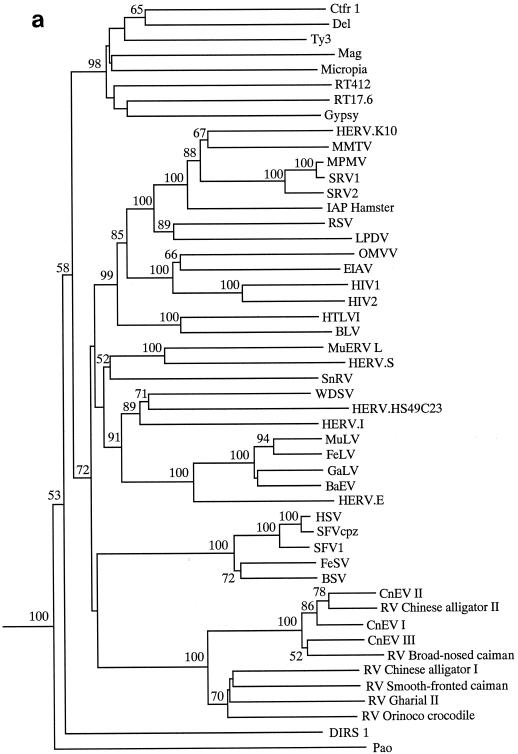

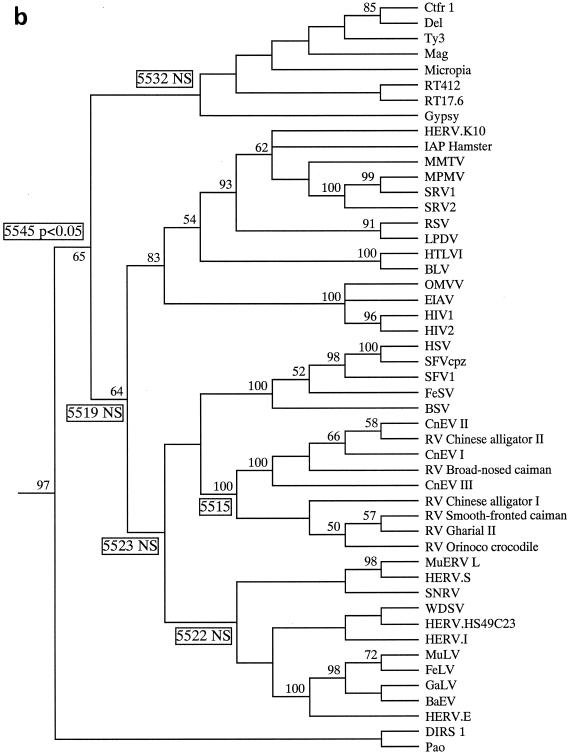

We next constructed phylogenies based on a 340-residue alignment of retroelement Pol polyproteins. Phylogenies were constructed using both the neighbor-joining (Fig. 1a) and maximum parsimony (Fig. 1b) approaches with PAUP (for phylogenetic analysis using parsimony) (16). Clustering of the crocodilian elements gained strong bootstrap support, but their relationship to other retroviruses was not strongly supported. Although all trees placed the crocodilian virus group within the Retroviridae, the actual position of group members varied somewhat depending on the exact taxa within the data set. For this reason, we performed topological constraint analyses, forcing the crocodilian elements into certain locations and comparing the resulting tree to the best or minimum tree (length, 5,515 steps) (Fig. 1b). Only four to eight extra steps were required to place the crocodilian group in several locations within the phylogeny, usually clustering with (or close to) the spumaviruses or basal to all retroviral branch elements. A higher number of steps (5,532) were required to place the crocodilian elements as sister taxa to the gypsy-type LTR retrotransposons, with 5,545 steps needed to place these elements basal to a clade containing both the gypsy-type LTR retrotransposons and the Retroviridae. Only the last placement was significantly unlikely, using the Kishino-Hasegawa test (12), although some trees placing the crocodilian elements next to the gypsy-type LTR retrotransposons had scores of P < 0.1.

FIG. 1.

Relationship of the crocodilian elements to other retroviruses. The alignment was based on the following regions of CnEVI (accession number AJ438130): positions 2720 to 3379 within RT; positions 4063 to 4102, 4166 to 4202, 4241 to 4268, and 4406 to 4427 within RnaseH; and positions 4685 to 4700, 4760 to 4841, and 4871 to 5042 within Int. (a) Neighbor-joining phylogram using the Protpars matrix. Figures on each branch show percent bootstrap support from 1,000 replicates. (b) Strict consensus of three maximum parsimony trees (length, 5,515 steps) using an unordered matrix. Unboxed figures on each branch represent the percent bootstrap values from 100 replicates. Boxed figures represent the number of steps required when the crocodilian group was placed in that location (e.g., forcing the crocodilian elements to be positioned basal to all other retroviral taxa required 5,519 steps). NS, the placement of the crocodilian taxa in that location did not result in a tree which was significantly worse than the minimum tree presented (according to the Kishino-Hasegawa test). A P value is provided if the tree score was significantly worse than that for the minimum tree.

Thus, although our phylogenetic analyses were unable to determine the exact relationships of the crocodilian group to other retroelements, they did suggest that these elements are highly likely to lie within, or basal to, the Retroviridae. Trees placing the crocodilian elements outside the Retroviridae required at least 17 additional steps over the minimum tree shown in Fig. 1b, and such topologies were never observed during analyses. Furthermore, LTR retrotransposons almost never use a hairpin-mediated gag-pol frameshift and usually lack a myristylated Gag protein, and these features are both present within the CnEVI genome.

Despite their probable placement within the Retroviridae, clearly the crocodilian elements are very distantly related to other members of this family. This is most obviously demonstrated by the relatively long branches leading to the group shown in Fig. 1a and the low percent identity scores shown in Table 2. Consistent with this was the lack of obvious sequence similarity to other retroviruses within gag and most regions of RNaseH, protease, and Int.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The PCR-amplified sequences and full-length elements have been submitted to the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases (accession numbers AJ438133 to AJ438138 for the PCR fragments and AJ438130 to AJ438132 for CnEVI to -III).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Gatesy (American Museum of Natural History) for the crocodile samples. We thank A. Trnka for providing crocodile liver samples. Thanks also to C. Lynch and A. Burt for discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal, R. K., K. C. Majumdar, J. W. Lang, and L. Singh. 1994. Generic affinities among crocodilians as revealed by DNA fingerprinting with a Bkm-derived probe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10601-10605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeke, J. D., and J. P. Stoye. 1997. Retrotransposons, endogenous retroviruses, and the evolution of retroelements, p. 343-435. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 3.Chamorro, M., N. Parkin, and H. E. Varmus. 1992. An RNA pseudoknot and an optimal heptameric shift site are required for highly efficient frameshifting on a retroviral messenger RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:713-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X., M. Chamorro, S. I. Lee, L. X. Shen, J. V. Hines, I. J. Tinoco, and H. E. Varmus. 1995. Structural and functional studies of retroviral RNA pseudoknots involved in ribosomal frameshifting: nucleotides at the junction of the two stems are important for efficient ribosomal frameshifting. EMBO. J. 14:842-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doolittle, R. F., D. F. Feng, M. S. Johnson, and M. A. McClure. 1989. Origins and evolutionary relationships of retroviruses. Q. Rev. Biol. 64:1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eickbush, T. H. 1994. Origin and evolutionary relationships of retroelements, p. 121-157. In S. S. Morse (ed.), The evolutionary biology of viruses. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 7.Flavell, A. J., S. R. Pearce, P. Heslop-Harrison, and A. Kumar. 1997. The evolution of Ty1-copia retrotransposons in eukaryote genomes. Genetica 100:185-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart, D., N. Frerichs, A. Rambaut, and D. E. Onions. 1996. Complete nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the snakehead fish retrovirus. J. Virol. 70:3606-3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herniou, E., J. Martin, K. Miller, J. Cook, M. Wilkinson, and M. Tristem. 1998. Retroviral diversity and distribution in vertebrates. J. Virol. 72:5955-5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirose, Y., M. Takamatsu, and F. Harada. 1993. Presence of env genes in members of the RTLVH family of human endogenous retrovirus-like elements. Virology 192:52-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holzschu, D. L., D. Martineau, S. K. Fodor, V. M. Vogt, P. R. Bowser, and J. W. Casey. 1995. Nucleotide sequence and protein analysis of a complex piscine retrovirus, walleye dermal sarcoma virus. J. Virol. 69:5320-5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishino, H., and M. Hasegawa. 1989. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in Hominoidea. J. Mol. E 29:170-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mager, D. L., and P. S. Henthorn. 1984. Identification of a retrovirus-like repetitive element in human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7510-7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, J., E. Herniou, J. Cook, R. W. O'Neill, and M. Tristem. 1999. Interclass transmission and phyletic host tracking in murine leukemia virus-related retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:2442-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanstrom, R., and J. W. Wills. 1997. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins, p. 263-334. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 16.Swofford, D. L. 1998. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 17.Tristem, M. 2000. Identification and characterization of novel human endogenous retrovirus families by phylogenetic screening of the human genome mapping project database. J. Virol. 74:3715-3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tristem, M., E. Herniou, K. Summers, and J. Cook. 1996. Three retroviral sequences in amphibians are distinct from those in mammals and birds. J. Virol. 70:4864-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tristem, M., T. Myles, and F. Hill. 1995. A highly divergent retroviral sequence in the tuatara (Sphenodon). Virology 210:206-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Regenmortel, M. H. V., C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.). 2000. Virus taxonomy: the classification and nomenclature of viruses, p. 369-387. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 21.Vogt, V. M. 1997. Retroviral virions and genomes, p. 27-69. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 22.Xiong, Y., and T. H. Eickbush. 1990. Origin and evolution of retroelements based upon their reverse transcriptase sequences. EMBO J. 9:3353-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]