Abstract

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), the most frequent malignancy afflicting AIDS patients, is characterized by spindle cell formation and vascularization. Infection with KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is consistently observed in all forms of KS. Spindle cell formation can be replicated in vitro by infection of dermal microvascular endothelial cells (DMVEC) with KSHV. To study the molecular mechanism of this transformation, we compared RNA expression profiles of KSHV-infected and mock-infected DMVEC. Induction of several proto-oncogenes was observed, particularly the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit. Consistent with increased c-Kit expression, KHSV-infected DMVEC displayed enhanced proliferation in response to the c-Kit ligand, stem cell factor (SCF). Inhibition of c-Kit activity with either a pharmacological inhibitor of c-Kit (STI 571) or a dominant-negative c-Kit protein reversed SCF-dependent proliferation. Importantly, inhibition of c-Kit signal transduction reversed the KSHV-induced morphological transformation of DMVEC. Furthermore, overexpression studies showed that c-Kit was sufficient to induce spindle cell formation. Together, these data demonstrate an essential role for c-Kit in KS tumorigenesis and reveal a target for pharmacological intervention.

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (or human herpesvirus 8) is consistently associated with all epidemiologic forms of KS and is recognized as the etiologic agent of the disease (15, 27). Within the KS lesion, KSHV infects the spindle-shaped cells that characterize the tumor as well as their endothelial cell precursors (15, 62, 100). The majority of infected cells harbor the KSHV genome in a latent form, with a small percentage entering a lytic cycle and producing infectious virus (82, 102, 116).

KSHV genes with the potential to deregulate cellular growth have been described previously. Several of these genes have homology to human oncogenes and growth factors or transforming genes of other oncogenic herpesviruses, while others are unique to KSHV (33). KSHV regulatory gene products include homologs of cellular cytokines (viral interleukin-6 [vIL-6]) (70) and chemokines (viral macrophage inflammatory protein I [vMIP-I]/open reading frame K4 [ORF K4], vMIP-II/ORF K6, and vMIP-III/ORF K4.1) (13); the antiapoptotic proteins viral B-cell lymphoma 2 [vBCL-2]/ORF16 (30) and viral FLICE-inhibitory protein [vFLIP]/ORF71 (106); an inhibitor of interferon signaling (viral interferon regulatory factor [vIRF]/ORF K9) (44); a cyclin D homolog (viral cyclin [vCYC]/ORF72) (28); a viral G-protein-coupled receptor (vGCR) with homology to the IL-8 receptor (vGCR/ORF74) (9, 23); the viral protein Kaposin (ORF K12) (116), which has been shown to have transforming ability (73); and the latent nuclear antigen (LANA/ORF73), which modulates cellular transcription (84). Interestingly, three of these gene products, LANA, vFLIP and vCYC are thought to constitute the latent gene expression program in KSHV and are consistently expressed in all virally infected cells in KS, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) (34, 36, 102). Other gene products such as the vGCR and vIL-6 are expressed in a minority of infected tumor cells in vivo (20, 47, 99). While lytic infection may not be compatible with transformation, lytic gene products are thought to have important paracrine effects on adjacent latently infected or uninfected cells that are vital for lesion formation. In addition, viral gene expression patterns may be tumor or stage specific, and some early lytic genes may be expressed for an extended period of time in the absence of a complete replication cycle. Thus, KSHV encodes an arsenal of proteins that could conceivably induce and/or maintain KS lesions. Despite this recognition, the mechanisms of virus-induced oncogenesis remain unclear.

In vitro studies with KSHV were initially performed using PEL cell lines established from PEL tumors that comprise a rare form of AIDS-associated B-cell lymphoma (7, 14, 22). PEL cells stably maintain KSHV episomes, and lytic viral replication can be induced in a significant percentage (>30%) of cells following treatment with phorbol esters or sodium butyrate. PEL cells have thus proved invaluable for mapping and characterizing the KSHV genome (75, 86, 93, 103) and have provided a source of infectious KSHV for infection of other cell types. In addition, DNA array analysis of PEL cells has been used to map the transcription program of KSHV (57, 78). Endothelial cells are, however, a more relevant cell type in which to study KS pathogenesis, since they are the likely precursors of KS spindle cells (11, 90, 91, 96). Interestingly though, cells cultured from KS tumors do not maintain the KSHV genome (3, 4), and the early consequences of cellular transformation are inaccessible via the study of fully transformed tumor cells. In vitro endothelial cell models of KSHV infection thus provide the most useful systems with which to dissect the role of KSHV in KS spindle cell development and growth, but development of such systems has proved to be challenging. To date several endothelial-based models of KSHV infection have been described (31, 42, 60, 71). Each model has unique characteristics and has thus contributed distinct but complementary information to the field. The system described by Flore et al. highlights the role played by paracrine signaling, since only a percentage of cells harbor the viral genome (42). Other systems describe endothelial cell cultures in which latent infection predominates, but only that characterized by Ciufo et al. utilizes primary cells (31). The other models utilize dermal microvascular endothelial cells (DMVEC) first immortalized by human papillomavirus (HPV) gene products (71) or telomerase (60), since primary endothelial cells have a limited life span in vitro. While prior immortalization precludes a strict analysis of the effect of the virus on cell survival, it does allow for a long-term maintenance of infected cells and the robust growth of mock-infected controls.

To identify the molecular mechanisms involved in KSHV-induced endothelial cell transformation, we applied gene expression profiling by cDNA arrays to KSHV-infected DMVEC. We chose the KSHV-permissive immortalized DMVEC system as previously described (71) for the gene profiling studies since this system allows us to generate age- and passage-matched KSHV- and mock-infected cells. This system duplicates many features of a natural infection of KS spindle cells. For example, KSHV remains latent in the majority of DMVEC infected in vitro, with virus in approximately 2% of cells entering the lytic replication cycle. In addition, latently infected DMVEC change from cobblestone to spindle morphology and exhibit features of transformation including loss of contact inhibition and growth in soft agar. Immortalization results in a very robust and reproducible infection system. To identify cellular genes that may contribute to KSHV-induced transformation, we used cDNA arrays for gene expression profiling of age- and passage-matched KSHV-infected and uninfected DMVEC. Induction of several proto-oncogenes was observed, including the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit. c-kit induction was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis, while immunofluorescent staining confirmed upregulation of the c-Kit protein in primary as well as immortalized KSHV-infected DMVEC. Importantly, infected DMVEC displayed a ligand-dependent growth advantage that could be eliminated by STI 571 (Gleevec) a pharmacological inhibitor of c-Kit activity (50). Moreover, we show that c-Kit was sufficient for induction of the transformed phenotype in DMVEC and that specific inhibition of c-Kit signaling reversed this phenotype in KSHV-infected cells. Abnormal c-Kit signaling due to receptor overexpression and/or constitutive activation has been implicated in a variety of cancers (12, 63). Our results suggest that KSHV may contribute to KS development through modulation of c-Kit expression and function and, further, identify this cellular proto-oncogene as a novel target for therapeutic intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Derivation of KSHV-infected DMVEC.

KSHV-infected DMVEC were established as previously described in detail (71). Briefly, DMVEC immortalized by retroviral expression of the E6 and E7 genes of HPV type 16 (DMVEC) were infected with KSHV derived from the supernatant of tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate-stimulated BCBL-1 cells. DMVEC were maintained in endothelial-SFM (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% human AB serum (HS; Sigma, St Louis, Mo.), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 2 mM glutamine, endothelial cell growth supplement (25 μg/ml; Becton Dickinson, Bedford, Mass.), heparin (40 μg/ml; Sigma) and G418 (200 μg/ml; GIBCO BRL). The BCBL-1 cell line was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (contributed by Michael McGrath and Don Ganem) and cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 2 mM glutamine, and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. KSHV infection of DMVEC was verified by DNA PCR for amplification of the KS330 BamHI fragment of the ORF26 gene, and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for the spliced mRNA from the ORF29 gene (85). DMVEC were used for experiments when >90% of cells expressed ORF73 (LANA). Typically, 2% of infected cells in such LANA-positive cultures expressed the early lytic protein ORF59/PF-8 (24) and <1% of PF-8-positive cells expressed the late lytic glycoprotein protein ORF K8.1A/B (26). Viral antigen expression was detected by immunofluorescent staining as previously described (71). Antibodies against viral proteins were a generous gift from Bala Chandran. Where specified, primary DMVEC (pDMVEC) were obtained from Clonetics (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) and maintained as described for immortalized DMVEC but without selection. pDMVEC were infected with a recombinant strain of KSHV that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the elongation factor-1 promoter (GFP-KSHV). This virus was constructed and generously provided by Jeffry Vieira (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Wash.). Infection of GFP-positive cells was initially confirmed by simultaneous detection of ORF73 by immunofluorescent staining.

RNA isolation and fluorescent labeling.

RNA was isolated approximately 4 weeks after initial infection when >90% of the cells were LANA positive and showed the spindle cell phenotype. The two infected cultures designated I-8 and I-9 were harvested simultaneously with a mock-infected control culture. RNA was isolated from T75 flasks containing approximately 5 × 106 cells using the RNeasy RNA isolation kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, Calif.). After DNase treatment and another round of RNeasy purification, Cy-3 labeled cDNA was prepared as described previously (92, 97). Briefly, poly(A) RNA was selectively amplified by one round of T7-polymerase-based linear amplification. The resulting cRNA was converted into Cy-3-labeled cDNA by reverse transcriptase.

cDNA microarrays.

Arrays were generated at the R. W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Research Institute as previously described (97). IMAGE Clones were obtained from commercial sources (Research Genetics, Huntsville, Ala.), and sequences were verified prior to PCR amplification. Arrays were printed onto silane-coated slides (Corning) using a Generation III microarray spotter (Molecular Dynamics) printer. Each clone was spotted twice on each slide at nonadjacent positions. Each slide was visually inspected prior to immobilization of the DNA by baking. Labeled samples were hybridized to the slides overnight at 42°C. Each sample was hybridized to two slides. Fluorescent signals were detected by a confocal scanner (Molecular Dynamics) and quantified using Autogene software (Biodiscovery, Los Angeles, Calif.). In addition, each slide was visually inspected for correct grid alignment, spot morphology, and signal consistency, and obviously bad spots were eliminated from further analysis. Raw data were scaled by calculating the ratio of the mean of the individual array to the mean of all arrays. Each intensity value was divided by this scaling factor. All data were log2 transformed. The mean intensity and coefficient of variation (CV) were determined for the four values obtained with each sample. Mean intensities with CV of >50% were excluded. Ratios were determined by comparing the mean intensity values of infected and noninfected samples. Background was set as the mean of the lowest 5% of signals. If both infected and noninfected signals were below this background threshold, changes were not considered significant. The complete data set can be viewed at http://www.ohsu.edu/vgti/fruehkshv.htm.

Real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Total RNA kit (QIAGEN, Inc.). RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I to remove any residual genomic DNA contamination (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). Quantification of RNA was performed by a two-step method. First, cDNA was synthesized using superscript II (Invitrogen). Synthesized cDNA was diluted in H2O to a final concentration of 2 ng per reaction mixture. Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI-PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). To compared mock- and KSHV-infected samples, relative quantification was performed as outlined in ABI user bulletin 2 (Relative quantitation of gene expression: ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system: user bulletin 2: Rev B). Depending on the primer efficiency validation, the standard curve method or comparative cycle threshold (CT) method was performed as outlined in user bulletin 2 (ABI). The comparative CT method compares the different samples by analyzing the differences in the threshold cycles between samples after normalization to an endogenous reference gene. Different concentrations of RNA transcripts between treatments will produce different CT values as the sample with more gene transcripts will amplify at a greater rate, producing an earlier threshold signal over background. The differences between samples during the exponential phase of PCR amplification were calculated by the following equation: ΔΔCT = (CT Target − CTGAPDH)infected − (CT Target − CTGAPDH)mock and converted to n-fold change units by the equation 2−ΔΔCT. To generate standard curves, Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was employed in a dilution scheme. If the target gene was not present in the Universal RNA sample, KSHV-infected DMVEC RNA was used to generate a relative standard curve. The samples were normalized to endogenous GAPDH. The following primers were generated using primer express v1.1 (ABI): Jun-D NM_005354 forward, 5′-AGTTCCTCTACCCCAAGGTGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGTGTAAATCCTCCAGGGCC-3′; UBE4A NM_0047880 forward 5′-TGGAGGAAAATGGGCACAAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGACTGGAGGCAGCATGGG-3′; neuritin NM_016588 forward, 5′-AGCGTATCTGGTGCAGGCC-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAAGCCCTTGAAGACCGCA-3′; CXADR NM_001338 forward, 5′-GCAGGGATAGATTTTGTTGGTGA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGCTGGCCACCATTTTGA-3′; ARHGEF6_D25304 forward, 5′-ACCATCCACAGGAAATGGACTATTT-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTTTACTCTTCAGCTTCCAAACACG-3′; CD36 NM_000072 forward 5′-GGAAAATGTAACCCAGGACGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAAGGTTCGAAGATGGCACC-3′; IGFBP2 NM_000597 forward, 5′-CTGTGACAAGCATGGCCTGTA-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCACACACCAGCACTCCCC-3′; IGFBP6 NM_002178 forward, 5′-AGGGTCTCCAGATGGCAATG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CCCCTCTATCCCCCAGCTT-3′; INSR NM_000208 forward, 5′-GGGACCGCTTTACGCTTCTT-3′, and reverse, 5′-ACTCGTCCGGCACGTACAC-3′; PPARG NM_005037 forward, 5′-CAAACACATCACCCCCCTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAACTGGCAGCCCTGAAAGA-3′; Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 NM_002165 forward, 5′-GAACCGCAAGGTGAGCAAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCCAACTGAAGGTCCCTGATG-3′; LIM domain only 2 NM_005574 forward, 5′-GACGGTCTCTGCGCATCCT-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGTCTTTCACCCGCATTGTC-3′; c-Mer proto-oncogene forward, 5′-CTGCACACGGTTGGGTAGATT −3′, and reverse, 5′-AGCACAGGATCTGCGTTGC-3′; cytochrome P450 forward, 5′-TCCAGCTTTGTGCCTGTCAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGGAATGTGGTAGCCCAAGA-3′; c-Kit ligand NM_000899K forward, 5′-CCAAAAGACTACATGATAACCCTCAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CATCTCGCTTATCCAACAATGACT-3′; monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) forward 5′-GCCAAGGAGATCTGTGCTGAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGTTTGCTTGTCCAGGTGGT-3′; and c-Kit X06182 forward 5′-CGGATCAATTCTGTCGGCA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CATCGTCGTGCACAAGCAG.

Reagents.

The 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative STI 571 (Gleevec) was developed and generously provided by Elisabeth Buchdunger (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). Stock solutions of STI 571 were prepared at 10 mmol/liter by dissolving 5 mg of STI 571 in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and used fresh or stored at −20°C. Working solutions were diluted in endothelial-SFM immediately prior to use.

Immunofluorescent staining.

For detection of c-Kit protein, DMVEC monolayers were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.02% sodium azide (staining buffer) and stained with an anti-c-Kit monoclonal antibody (clone 57A5 [Ancell, Bayport, Minn.] or Clone Nu-cKit [Research Diagnostics, Flanders, N.J.]) followed by a goat anti-mouse fluorescently labeled secondary conjugate (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.). For mock- and KSHV-infected DMVEC, or DMVEC infected with a c-Kit recombinant adenovirus (described below), a FITC-labeled second conjugate was used. For pDMVEC infected with GFP-KSHV, a rhodamine conjugate was used to allow simultaneous visualization of GFP in infected cells. All antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution in staining buffer and incubated with cell monolayers for 60 min at 37°C. Primary antibody was omitted from duplicate monolayers to control for nonspecific binding of secondary conjugate. Stained cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, mounted, and examined on a Nikon fluorescent microscope.

Proliferation assays.

Proliferation of mock- and KSHV-infected DMVEC was quantified using a standard colorimetric assay based on bioreduction of the tetrazolium salt XTT(Roche, Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). DMVEC were plated in Primaria 96-well trays (Becton Dickinson) at 5 × 104 cells/well and cultured in endothelial-SFM containing 1% HS and lacking additional growth supplements (basal medium). Recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF) (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, Mass.) (20, 50, 100 and 200 ng/ml) or SCF (50 ng/ml) and STI 571 (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 μM) were added in fresh basal medium 24 h after plating as designated by the experimental protocol. XTT was added 48 h later according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance (490 nm) was read after 4 to 6 h on a Dynatech MR5000 microplate reader. The Jurkat human T cell line (JJK subline) was provided by Dan Littman. Jurkat cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 96-well trays in RPMI containing 5% FBS in the presence or absence of 50U/ml IL-2 (Sigma) and STI 571 (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 μM) and proliferation was measured at 48 h as described above.

Transformation assays.

To promote a transformed phenotype, KSHV-infected DMVEC were cultured postconfluency in 35-mm-diameter Primaria culture dishes. Under these conditions, cells assumed a pronounced spindle morphology, exhibited a disorganized growth pattern, and developed multilayered foci within the monolayer. Uninfected DMVEC cultured under similar conditions displayed growth inhibition and maintained a cobblestone phenotype with organized cell borders. Postconfluent cells were exposed to increasing doses of STI 571 (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM) that were replenished every 36 to 48 h using dilutions freshly prepared from a frozen stock. In other experiments, postconfluent cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing a dominant negative c-Kit protein (described below). DMVEC were examined daily for evidence of phenotypic change using a phase-contrast microscope and results recorded photographically.

Construction and use of adenovirus vectors.

For overexpression of c-Kit in DMVEC in the absence of KSHV infection, full-length human c-Kit cDNA (65) was cloned into an adenoviral expression vector as previously described (101) to create a recombinant adenovirus expressing wild type c-Kit (Ad/c-KitWT). This places Ad/c-KitWT under the control of a tet-regulated promoter-enhancer element, and protein expression is driven by coinfection with an adenovirus expressing the requisite transactivator (Ad/trans). A dominant-negative c-Kit mutant (Ad/c-KitDN) was constructed by insertion of a premature stop codon at Ser614 in the cytoplasmic domain using standard PCR-based mutagenesis. Truncation of c-Kit at this site deletes the ATP-binding and phosphotransferase domains without affecting the dimerization domain. Following DNA sequence analysis to confirm correct mutagenesis, Ad/c-KitDN was similarly cloned into an adenoviral expression vector. Recombinant viruses were screened by PCR, and protein expression was confirmed by western immunoblot of infected cell lysates using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the N terminus of c-Kit (H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.). Recombinant adenoviruses were plaque purified, and viral stocks were grown and their titers were determined on 293 cells. For DMVEC infection, monolayers were incubated with Ad/c-KitWT or Ad/c-KitDN at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 and 100 and Ad/trans at an MOI of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. Optimal MOI doses were previously determined, and virus stocks were diluted in medium containing 2% human serum and Polybrene (4 μg/ml; Sigma) for infection. As a control for infection efficiency and nonspecific effect of adenovirus infection, duplicate monolayers were infected with an adenovirus vector expressing green fluorescent protein (Ad/GFP). Infection with Ad/GFP and Ad/trans at MOI of 100 and 10, respectively, allowed infection of >80% of cells in culture with minimal cytopathic effect.

RESULTS

DNA-microarray analysis of KSHV-infected DMVEC.

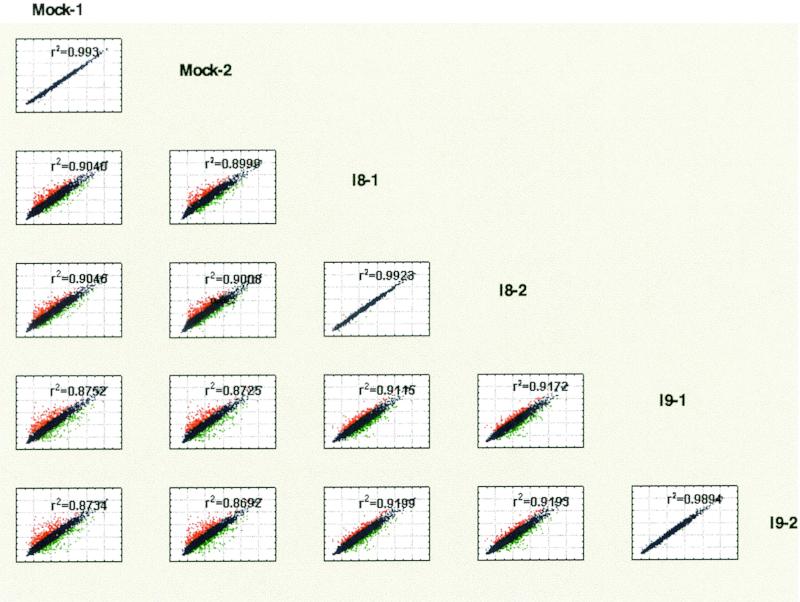

DMVEC cultures immortalized with HPV-E6/E7 (DMVEC) were either mock infected or infected with two different stocks of KSHV derived from the BCBL-1 PEL cell line as previously described (71). Each infected culture was propagated separately for approximately 4 weeks until >90% of cells were latently infected, as determined by spindle morphology and expression of LANA (data not shown). Mock-infected cells were grown and harvested in parallel. Total RNA was isolated, labeled with Cy-3, and hybridized to cDNA arrays displaying a total of 4,165 clones in duplicate. Each RNA sample was hybridized to two arrays. Comparison of the signal intensities between the two arrays probed for each sample revealed a low interarray variation (Fig. 1). When the expression profiles of the two infected cell lines (designated I-8 and I-9) were compared to each other and to the mock-infected culture, the infected cultures were more closely correlated to each other than to the mock-infected cells (Fig. 1). However, differences in expression profiles between the two infected cultures also became apparent. To account for this experimental variation, we considered only genes that were up- or downregulated ≥1.8-fold in both infected cell lines compared to the mock-infected cell line. These ratios were calculated using the mean of the intensities of both replicate chips, i.e., a total of four measurements per gene for each of the three samples. Only those results with a CV of <50% were included. Approximately 45% of the clones that changed more than twofold in one of the infected cell cultures, also changed significantly in the other experiment resulting in 184 clones changing significantly in both experiments. The ratios for these differentially expressed genes are shown in Table 1. If several clones represented the same gene, results for all individual clones are shown. The complete data set can be viewed at http://www.ohsu.edu/vgti/fruehkshv.htm.

FIG. 1.

Comparison matrix of normalized intensity values from microarray slides by scatter plot. Normalized logarithmic intensity values obtained from each individual array were compared between each sample and depicted as a scatter plot. The annotation of the x axis is shown to the right of the matrix, whereas the y axis annotation is shown on top. Values that differ more than 1.8-fold are shown in red (high) or green (low). Also shown is the correlation coefficient r2 for each comparison. The highest correlation was observed when for results obtained from the same sample hybridized to two arrays. Comparisons between the two different infected samples, I-8 versus I-9, were more similar to each other than comparisons between infected samples and mock-infected DMVEC isolated in parallel.

TABLE 1.

Genes modulated in DMVEC after KSHV infectionb

| UG Cluster | Gene ID | Symbol | cDNA array value for:

|

Name | Function | Groupa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I8 | I9 | ||||||

| Hs.75613 | N39161 | CD36 | 14.9 | 27.0 | CD36 (thrombospondin receptor) | Platelet-collagen adhesion | A |

| Hs.110802 | AA487787 | VWF | 4.6 | 9.3 | von Willebrand factor | Antihemophilic factor carrier | A |

| Hs.12337 | AA026831 | KDR | 3.9 | 4.3 | VEGF receptor 2 | Vascular development, angiogenesis | A |

| Hs.75716 | T49159 | SERPINB2 | 2.3 | 2.9 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 | Angiogenesis | A |

| Hs.295944 | L27624 | TFPI2 | −2.1 | −3.5 | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 | Inhibit trypsin, factor VII(a)/tissue factor | A |

| Hs.1908 | AA278759 | PRG1 | −2.1 | −9.3 | Proteoglycan 1, secretory granule | Tissue development and maintenance | A |

| Hs.77274 | AA284668 | PLAU | −2.8 | −10.6 | Urokinase plasminogen activator | Angiogenesis | A |

| Hs.8966 | H58644 | TEM8 | −5.0 | −16.7 | Anthrax toxin receptor | Elevated during tumor angiogenesis | A |

| Hs.78146 | R22412 | PECAM1 | 2.7 | 1.8 | CD31 | Expressed on cell intercellular junctions | A |

| Hs.268107 | AA423867 | MMRN | 9.3 | 5.0 | Endothelial cell multimerin precursor | Extracellular matrix, adhesion | CA |

| Hs.81337 | AA434102 | LGALS9 | 3.3 | 2.4 | Lectin, galactoside binding | Cell adhesion | CA |

| Hs.50964 | AA411757 | CEACAM1 | 2.7 | 3.5 | CD66 antigen | Cell adhesion | CA |

| Hs.2340 | R06417 | JUP | 2.0 | 2.4 | Junction plakoglobin | Cell adhesion | CA |

| Hs.118787 | R31321 | TGFBI | −2.6 | −2.9 | Transforming growth factor | Inhibits cell adhesion | CA |

| Hs.36131 | AA167222 | COL14A1 | −3.3 | −3.5 | Collagen, type XIV, alpha 1 | Interacts with type I collagen | CA |

| Hs.179573 | AA490172 | COL1A2 | −4.5 | −10.1 | Collagen, type I, alpha 2 | Fibrillar forming collagen | CA |

| Hs.156346 | AA504348 | TOP2A | 4.3 | 4.7 | Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha | DNA synthesis | CD |

| Hs.69563 | H59203 | CDC6 | 3.7 | 2.6 | CDC6 homolog | Cell growth and differentiation | CD |

| Hs.239 | AA129552 | FOXM1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | Forkhead box M1 | Cell proliferation | CD |

| Hs.85137 | AA608568 | CCNA2 | 3.4 | 2.6 | Cyclin A2 | Regulators of CDK kinases | CD |

| Hs.156346 | AA504348 | TOP2A | 3.2 | 3.2 | Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha | DNA replication | CD |

| Hs.84113 | AA284072 | CDKN3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 | Cell growth and differentiation | CD |

| Hs.166563 | H73714 | RFC1 | 2.6 | 2.3 | Replication factor C (activator 1) 1 | Activator of DNA polymerases | CD |

| Hs.348669 | AA459292 | CKS1 | 2.6 | 2.2 | CDC28 protein kinase 1 | Cell growth and differentiation | CD |

| Hs.79069 | AA489752 | CCNG2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | Cyclin G2 | Regulators of CDK kinases | CD |

| Hs.75586 | H84153 | CCND2 | 2.2 | 2.7 | Cyclin D2 | Regulators of CDK kinases | CD |

| Hs.179565 | AA455786 | MCM3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | DNA replication licensing factor mcm3 | Associates with DNA polymerase | CD |

| Hs.78996 | AA450265 | PCNA | 2.0 | 2.1 | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | Cell growth and differentiation | CD |

| Hs.115474 | H94617 | RFC3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | Replication factor C (activator 1) 3 | DNA strand elongation | CD |

| Hs.154762 | W52273 | HRB2 | −1.9 | −3.8 | HIV-1 rev binding protein 2 | May be required for cell division | CD |

| Hs.256290 | AA464731 | S100A11 | −2.0 | −3.7 | S100 calcium binding protein A11 | Cell cycle progression, differentiation | CD |

| Hs.514 | AA454146 | CCNH | −2.4 | −2.0 | Cyclin H | Regulators of CDK kinases | CD |

| Hs.103291 | R66101 | LOC51299 | 5.0 | 7.7 | Neuritin | Neurite outgrowth | CS |

| Hs.296842 | AA490477 | 4.0 | 6.4 | Similar to nonmuscle myosin | Cytokinesis and cell shape | CS | |

| Hs.79226 | H20758 | FEZ1 | 3.8 | 3.5 | Zeta 1 | Axonal outgrowth | CS |

| Hs.195850 | AA160507 | KRT5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | Keratin 5 | Intermediate filament family | CS |

| Hs.79307 | AA236617 | ARHGEF6 | 2.2 | 3.1 | Rac/Cdc42 guanine exchange factor 6 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | CS |

| Hs.121576 | W95682 | MYO1B | 2.0 | 3.1 | Myosin IB | Cytoskeleton | CS |

| Hs.182265 | AA464250 | KRT19 | 1.8 | 1.8 | Keratin 19 | Cytoskeletal structural protein | CS |

| Hs.160483 | R62868 | EPB72 | 1.8 | 2.4 | Erythrocyte membrane protein | Cytoskeleton | CS |

| Hs.24178 | R27680 | EML2 | −1.9 | −2.5 | Microtubule-associated protein-like protein 2 | Assembly dynamics of microtubules | CS |

| Hs.155524 | T64878 | PNUTL2 | −1.9 | −2.0 | Peanut-like 2 (Drosophila) | Cytoskeletal organization | CS |

| Hs.12451 | AA447196 | EML1 | −3.7 | −7.1 | Microtubule-associated protein-like protein 1 | Assembly dynamics of microtubules | CS |

| Hs.303649 | AA425102 | SCYA2 | 7.0 | 9.2 | Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 | Inflammation | H |

| Hs.20144 | R96668 | SCYA14 | 5.5 | 38.9 | CC-chemokine 14 | Inflammation | H |

| Hs.182579 | R69307 | LOC51056 | 5.1 | 2.2 | Leucine aminopeptidase | Interferon gamma induced | H |

| Hs.83429 | H54629 | TNFSF10 | 4.2 | 3.8 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily | Induces apoptosis | H |

| Hs.82112 | AA464525 | IL1R1 | 3.8 | 7.8 | Interleukin 1 receptor, type I | Cell signalling | H |

| Hs.285401 | AA279147 | CSF2RB | 3.3 | 2.1 | Colony-stimulating factor 2 receptor | High-affinity receptor for IL-3, IL-5, CSF | H |

| Hs.44532 | N49629 | UBD | 2.0 | 2.8 | Diubiquitin | Gamma interferon induced | H |

| Hs.237356 | AA447115 | SDF1 | −2.0 | −2.3 | Stromal cell-derived factor 1 | Chemokine | H |

| Hs.12013 | T70122 | ABCE1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | ATP-binding cassette | Antipathogen response | H |

| Hs.1869 | AA488504 | PGM1 | 5.3 | 3.3 | Phosphoglucomutase 1 | Breakdown and synthesis of glucose | M |

| Hs.154654 | AA448157 | CYP1B1 | 5.1 | 10.9 | Cytochrome P450, subfamily I | Drug metabolims and lipid biosynthesis | M |

| Hs.84190 | R49999 | SLC19A1 | 4.3 | 6.6 | Solute carrier family 19, member 1 | Folate transport | M |

| Hs.76057 | AA281030 | GALE | 2.5 | 2.5 | Galactose-4-epimerase, UDP− | Galactose metabolism | M |

| Hs.268012 | W31074 | FACL3 | 2.5 | 2.1 | Fatty-acid-coenzyme A ligase | Lipid synthesis and fatty acid degradation | M |

| Hs.59403 | AA160852 | SPTLC2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | Serine palmitoyltransferase | Sphingolipids | M |

| Hs.183556 | T70098 | SLC1A5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | Solute carrier family 1, member 5 | Neutral amino acid transporter | M |

| Hs.75694 | AA482198 | MPI | 2.1 | 2.7 | Mannose phosphate isomerase | Mannosylation | M |

| Hs.183868 | N34827 | GUSB | 1.9 | 3.5 | Glucuronidase, beta | Degradation of dermatan sulfates | M |

| Hs.75736 | H15842 | APOD | 1.8 | 10.5 | Apolipoprotein D | Lipoprotein metabolism | M |

| Hs.251415 | N74025 | DIO1 | −1.8 | −6.2 | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type I | Oxidoreductase | M |

| Hs.73875 | H44956 | FAH | −2.0 | −2.0 | Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase | Fumarylacetoacetase | M |

| Hs.234642 | R91904 | AQP3 | −2.2 | −2.3 | Aquaporin 3 | Small molecule transport | M |

| Hs.306098 | R93124 | AKR1C1 | −2.3 | −2.8 | Dihydrodiol dehydrogenase | Metabolizes xenobiotics | M |

| Hs.81454 | T61308 | KHK | 1.8 | 2.0 | Ketohexokinase (fructokinase) | Transferase | M |

| Hs.576 | N95761 | FUCA1 | 1.9 | 1.8 | Fucosidase, alpha-L-1, tissue | Glycosyl hydrolases | M |

| Hs.79187 | N31467 | CXADR | 7.2 | 8.6 | Coxsackie virus/adenovirus receptor | Pathogenic invasion | O |

| Hs.75737 | AA164439 | PCM1 | 3.9 | 3.3 | Perioentriolar material 1 | Interacts with centrosome | O |

| Hs.3314 | AA070226 | SEPP1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | Selenoprotein P, plasma, 1 | Oxidative stress response | O |

| Hs.284186 | AA495846 | 3.2 | 3.3 | Transcription factor forkhead-like 7 | Binding of freac-3 and freac-4 | O | |

| Hs.74471 | AA487623 | GJA1 | 2.3 | 2.2 | Gap junction protein, alpha 1 | Cell-to-cell communication | O |

| Hs.153487 | AA485996 | STAM | −1.8 | −2.0 | Signal transducing adaptor molecule 1 | Signal transduction | O |

| Hs.234680 | H26176 | FER1L3 | −2.1 | −3.8 | Myoferlin (for-1 like protein 3) | Role in membrane regeneration | O |

| Hs.13046 | AA453335 | TXNRD1 | −2.1 | −3.9 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Thioredoxin reductase (NADPH) | O |

| Hs.36927 | AA485036 | HSP105B | −2.1 | −1.8 | Heat shock 105kD | Heat shock response | O |

| Hs.75510 | AA465051 | ANXA11 | −2.6 | −2.3 | Annexin A11 | Phospholipid-binding protein | O |

| Hs.56023 | AA262988 | BDNF | −2.7 | −5.4 | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | Neural growth factor | O |

| Hs.89137 | AA464566 | LRP1 | −2.7 | −3.3 | Low-density lipoprotein-related protein | Binds to apoE-containing lipoproteins | O |

| Hs.296323 | H75599 | SGK | −2.7 | −3.2 | Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase | Stress response | O |

| Hs.135084 | AA599177 | CST3 | −3.4 | −2.1 | Cystatin C | Inhibitor of cysteine proteinases | O |

| Hs.8265 | R97066 | TGM2 | −3.6 | −4.5 | Transglutaminase 2 | Protein modification | O |

| Hs.790 | AA495936 | MGST1 | −6.6 | −9.4 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase | Conjugation of reduced glutathione | O |

| Hs.93002 | AA430504 | UBE2C | 4.3 | 3.5 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C | Ubiquitination | PD |

| Hs.155485 | H78483 | HIP2 | 3.3 | 2.0 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme e2-25 | Huntington interacting protein 2 | PD |

| Hs.75275 | AA447528 | UBE4A | 2.2 | 3.5 | Ubiquitination factor E4A | Ubiquitination | PD |

| Hs.1565 | AA442095 | NEDD4 | −1.9 | −9.0 | NEDD-4 | Ubiquitination | PD |

| Hs.84084 | AA046411 | APPBP2 | 6.8 | 3.6 | Amyloid beta precursor protein | Vesicie sorting | PS |

| Hs.20830 | N69491 | KNSL2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | Kinesin-like 2 | Microtubule gliding | PS |

| Hs.1050 | AA480859 | PSCD1 | 2.4 | 2.5 | Pleckstrin homology | Protein sorting, membrane trafficking | PS |

| Hs.91728 | AA458994 | PMSCL1 | 3.2 | 2.2 | Polymyositis/scleroderma autoantigen | 3 processing of the 7s pre-MA | PT |

| Hs.79306 | AA193254 | EIF4E | 3.0 | 1.8 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor | Transcription factor | T |

| Hs.78995 | AA234897 | MEF2C | 2.7 | 2.4 | MADS box transcription | Transcriptional activator | T |

| Hs.54452 | AA280931 | ZNFN1A1 | 2.4 | 2.2 | Zinc finger protein, subfamily 1A | Transcriptional activator | T |

| Hs.33287 | W87611 | NFIB | 2.2 | 2.9 | Nuclear factor I/B | Transcription regulation | T |

| Hs.81328 | W55872 | NFKBIA | 2.2 | 1.8 | NF-KAPPAB INHIBITOR ALPHA | Transcription factor | T |

| Hs.181163 | H93087 | HMG17 | 2.1 | 1.8 | High-mobility group protein 17 | Bind to nucleosomal DNA | T |

| Hs.154095 | AA443659 | ZNF143 | 2.0 | 3.9 | Zinc finger protein 143 | Transcriptional activator | T |

| Hs.79353 | W33012 | TFDP1 | 2.0 | 2.1 | Transcription factor Dp-1 | Transcription regulation | T |

| Hs.7943 | R63137 | RMP | −2.1 | −2.3 | RPB5-mediating protein | Transcription regulation from Pol II | T |

| Hs.159223 | AA434487 | NAB2 | −2.2 | −2.1 | NGFI-A binding protein 2 | Transcriptional corepressor | T |

| Hs.89657 | AA292583 | TAF10 | −2.4 | −1.8 | TAF10 RNA polymerase II | TFIID complex | T |

| Hs.159223 | AA434487 | NAB2 | −2.4 | −2.4 | NGFI-A binding protein 2 | Transcriptional repressor | T |

| Hs.2780 | AA418670 | JUND | 5.2 | 7.8 | jun-D proto-oncogene | Transcription regulation | TG |

| Hs.100724 | AA088517 | PPARG | 4.3 | 6.0 | PPAR gamma | Adipocyte differentiation | TG |

| Hs.75424 | AA457158 | ID1 | 4.0 | 6.1 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 | Transcription regulation | TG |

| Hs.184585 | AA464644 | LMO2 | 3.5 | 7.8 | LIM domain only 2 (rhombotin-like 1) | Hematopoietic development | TG |

| Hs.179718 | AA456878 | MYBL2 | 3.3 | 6.1 | Myb-related protein b (b-myb) | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.2969 | W69471 | SKI | 3.0 | 5.9 | ski oncogene | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.22026 | R16604 | 2.9 | 3.8 | Similar to transmembrane 4 | Expressed in endothelial cells and tumors | TG | |

| Hs.10526 | T59334 | CSRP2 | 2.7 | 2.3 | Cysteine-and glycine-rich protein 2 | Development and cellular differentiation | TG |

| Hs.81665 | N20798 | KIT | 2.6 | 5.0 | c-kit | Hematopoietic development | TG |

| Hs.117078 | AA436591 | 2.6 | 2.9 | Cellular proto-oncogene (c-mer) | Oncogenesis | TG | |

| Hs.31137 | T69540 | PTPRE | 2.4 | 2.6 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.89695 | AA001614 | INSR | 2.1 | 3.4 | Insulin receptor | Cell growth and maintenance | TG |

| Hs.162 | H79047 | IGFBP2 | 2.1 | 3.9 | IGF binding | Cell growth and differentiation | TG |

| Hs.1103 | R36467 | TGFB1 | 2.1 | 2.4 | Transforming growth factor, beta 1 | Proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis | TG |

| Hs.25155 | R24543 | NET1 | 1.9 | 2.7 | Neuroepithelial cell transforming gene | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.194143 | H90415 | BRCA1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | Breast cancer 1, BRCA 1 | Transcriptional activator | TG |

| Hs.326035 | AA486628 | EGR1 | 1.8 | 2.2 | Early growth response 1 | Transcriptional regulator | TG |

| Hs.61796 | AA399334 | TFAP2C | −1.8 | −2.1 | Transcription factor AP-2 gamma | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.129914 | AA425238 | RUNX1 | −2.0 | −1.4 | Runt-related transcription factor | Oncogenesis | TG |

| Hs.75551 | AA235332 | RSU1 | −2.2 | −1.8 | Ras suppressor protein 1 | Inhibits Ras signaling | TG |

| Hs.279860 | R09634 | TPT1 | −2.6 | −2.1 | Tumor protein | Unknown | TG |

| Hs.1298 | R98851 | MME | −5.4 | −8.1 | Membrane metallo-endopeptidase | Marker of acute lymphocytic leukemia | TG |

| Hs.23582 | AA454810 | TACSTD2 | −5.4 | −2.3 | Transducer 2 | Growth factor receptors | TG |

| Hs.274313 | AA478724 | IGFBP6 | −1.9 | −4.7 | Insulin-like growth factor binding | Cell growth inhibitor | TG |

| Hs.325823 | H69048 | 6.6 | 16.8 | Similar to ZN91 | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.325823 | R63109 | 4.9 | 8.0 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.170234 | R69677 | 4.7 | 14.0 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.38516 | W02617 | 4.6 | 12.0 | Similar to developmental protein | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.8769 | N57594 | BCMP1 | 3.9 | 4.2 | Brain cell membrane protein 1 | Homology to Wikott-Aldrich syndrome | |

| Hs.23044 | W00895 | MGC16386 | 3.5 | 3.1 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.107528 | T67558 | AIG-1 | 3.5 | 3.4 | Androgen-induced protein | Unknown | U |

| Hs.111577 | AA034213 | ITM3 | 3.5 | 6.3 | Integral membrane protein 3 | Unknown | U |

| Hs.51615 | T70413 | 3.2 | 4.7 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.16951 | R91083 | 2.9 | 3.8 | DKFZP586P2219 | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.16951 | T85698 | 2.9 | 3.5 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.28456 | R63982 | 2.9 | 3.4 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.28456 | H80158 | 2.9 | 8.9 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.107528 | R01796 | AIG-1 | 2.7 | 3.2 | Androgen-induced protein | Unknown | U |

| Hs.28783 | R23302 | KIAA1223 | 2.7 | 2.1 | KIAA1223 protein | Unknown | U |

| Hs.20558 | R70925 | FLJ20345 | 2.6 | 2.1 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.104859 | T66936 | 2.5 | 2.8 | DKFZp762E1312 | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.151334 | H65042 | 2.5 | 3.9 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.326416 | N55339 | 2.5 | 3.0 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.191558 | R06370 | 2.4 | 3.4 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.191558 | N91307 | 2.3 | 2.7 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.191558 | R79935 | 2.2 | 2.0 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.26516 | N72697 | FLJ10604 | 2.1 | 4.6 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.13041 | T67104 | 2.1 | 2.8 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.13041 | AA452909 | 2.1 | 3.6 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.13041 | AA430744 | 2.1 | 2.0 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.13041 | R28344 | 2.0 | 2.3 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.180059 | N67039 | 1.9 | 1.8 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.19717 | R11532 | 1.9 | 2.2 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.64313 | T66828 | 1.8 | 2.3 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.122546 | H83176 | FLJ23017 | 1.8 | 3.2 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.20654 | R10682 | 1.8 | 2.3 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.38163 | H63202 | 1.8 | 6.1 | Hypothetical protein | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.38163 | R06507 | 1.8 | 1.9 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.38163 | AA452909 | 1.8 | 3.3 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.23016 | N53172 | RDC1 | 1.8 | 4.6 | RDC1 G protein-coupled receptor | Unknown | U |

| Hs.18878 | R00332 | EGLN3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | EGL nine homolog 3 | Unknown | U |

| Hs.6349 | AA432023 | BC008967 | −1.8 | −2.6 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.37308 | H56438 | −1.8 | −1.9 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.187447 | T97870 | −1.8 | −2.4 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.37623 | H58834 | −1.8 | −1.9 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.79123 | AA457047 | KIAA0084 | −1.9 | −2.7 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.297929 | R67991 | −1.9 | −5.6 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.20588 | H66312 | PPY2 | −2.0 | −2.1 | Pancreatic polypeptide 2 | Unknown | U |

| Hs.165067 | H53316 | −2.0 | −3.3 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.170198 | AA459109 | KIAA0009 | −2.0 | −3.2 | Novel | Unknown | U |

| Hs.170198 | N91330 | −2.0 | −2.7 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.82141 | H64850 | −2.0 | −2.5 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.271686 | R87194 | −2.1 | −3.1 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.351310 | N69540 | −2.2 | −1.8 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.285519 | AA447098 | −2.2 | −3.4 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.285519 | AA455538 | −2.3 | −6.2 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.35453 | R95811 | −2.7 | −3.5 | cDNA DKFZp761G151 | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.78019 | H79234 | −2.9 | −2.6 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

| Hs.78019 | AA284568 | −3.3 | −3.6 | Novel | Unknown | U | |

Genes are organized into the following groups: A, angiogenesis; CA, cell adhesion; CD, cell division; CS, cell shape; H, host defense; M, metabolism; O, other; PD, protein degradation; PS, protein sorting; PT, protein translation; T, transcription; TG, tumorigenesis; U, unknown.

Boldface type indicates down regulated genes.

To confirm the cDNA array results by an independent method, real-time RT-PCR analysis on mock- and KSHV-infected samples was carried out for 16 selected genes. In addition to the RNA samples used for the array analysis, we also determined the RNA expression levels for these genes in two additional independently derived KSHV cultures in comparison to a parallel culture of mock-infected cells. Specific primers were selected based on the UniGene sequence containing the respective accession number. Relative quantification of gene expression in mock- and KSHV-infected samples was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. The ratios determined in comparison to mock-infected samples are shown in Table 2. The majority of the genes tested showed a higher induction or repression ratio when analyzed by real-time PCR compared to the array results. This may reflect the wider dynamic range of quantitative real-time PCR compared to cDNA array detection systems and is commonly observed when comparing cDNA array data and real-time PCR (80, 115). Importantly however, RT-PCR confirmed the induction or repression detected by cDNA array for the majority of the genes, both in the two KSHV-infected samples used for array analysis and in the two independently derived infected cultures.

TABLE 2.

Real-time PCR confirmation of cDNA data

| UG Cluster | cDNA array value for:

|

Quantitative RT-PCR result for:

|

Name | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I8 | I9 | I8 | I9 | B1 | B2 | ||

| Hs.75613 | 14.9 | 27.0 | 159.5 | 681.8 | 1.9 | 4.1 | CD36 (collagen type I receptor, thrombospondin receptor) |

| Hs.103291 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 40.5 | 2.8 | 3.0 | Neuritin |

| Hs.79307 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 9.2 | 23.6 | 2.8 | 2.1 | Rac/Cdc42 guanine exchange factor (GEF) 6 |

| Hs.303649 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 8.2 | MCP-1 |

| Hs.154654 | 5.1 | 10.9 | 41.5 | 30.1 | 10.1 | 14.7 | Cytochrome P450, subfamily 1 |

| Hs.79187 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 20.0 | 4.0 | 4.9 | Coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor |

| Hs.75275 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 | −2.0 | −1.3 | Ubiquitination factor E4A (homologous to yeast UFD2) |

| Hs.2780 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 2.8 | jun-D proto-oncogene |

| Hs.100724 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 8.7 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 3.1 | Peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma |

| Hs.75424 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 |

| Hs.184585 | 3.5 | 7.8 | 13.0 | 53.7 | 4.2 | 2.7 | LIM domain only 2 (rhombotin-like 1) |

| Hs.81665 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 23.6 | 44.5 | 157.6 | 89.0 | c-kit |

| Hs.117078 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 12.1 | 19.2 | 5.0 | 4.5 | Human cellular proto-oncogene (c-mer) |

| Hs.89695 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 10.7 | Insulin receptor |

| Hs.162 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 13.3 | 29.5 | 8.5 | 8.4 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 (36 kDa) |

| Hs.274313 | −1.9 | −4.7 | −1.9 | −4.8 | −27.5 | −35.2 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6 |

A functional description of the differentially expressed genes is shown in Table 1, and where possible, gene products are grouped into functional classes. Thirty-six of the clones that scored as upregulated genes in the cDNA array experiment, and 17 of the down-regulated clones, harbored sequences with unknown function. The remaining gene products were classified according to known functions in tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, host defense, cell adhesion, cell shape, cell division, transcription, metabolic pathways, or various other functions. With particular focus on those sequences that were confirmed by real-time PCR, we will discuss some of these gene products with respect to their potential involvement in KS.

Host defense genes.

Several of the KSHV-induced genes belonged to the interferon or proinflammatory pathways. Induction of interferon-regulated genes and pro-inflammatory genes is likely to reflect host cell defense mechanisms against KSHV infection and is often observed in virally infected cells (43). However, in contrast to what is seen with acute human cytomegalovirus infection (97), we did not detect a massive induction of the interferon-response genes in these experiments. The upregulation of the pro-inflammatory chemokine MCP-1 was confirmed by real-time PCR. MCP-1 (or CCL2) is a CC-chemokine that attracts mononuclear cells to sites of inflammation (72). Consistent with our observation, strong MCP-1 expression has also been noted in KS-derived spindle cells (94). The CC-chemokine 14 was also induced in our experiments. A potential role for this chemokine in inflammation is inferred from homology, but has not been demonstrated experimentally (77). One of the hallmarks of KS lesions is their abundant infiltration by macrophages, lymphoid cells, mast cells, and neutrophils (37). It is likely that KSHV-induced host genes such as MCP-1, in combination with viral genes such as vMIPs, contribute to this inflammatory process in vivo.

Cell adhesion and cell shape.

Infection of endothelial cells with KSHV generates a spindle cell morphology and induces focus formation (31, 60, 71). These phenotypic changes were reflected in the observed induction of genes regulating cell shape. The induction of two transcripts, neuritin and CDC42/Rac, was confirmed by real-time PCR. Neuritin has been shown to promote neurite outgrowth and arborization in primary neuronal cultures (74) and could thus be involved in the morphological changes seen in KSHV-infected DMVEC. CDC42/Rac is a major link between signaling pathways and the regulation of actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. Since CDC42 is involved in cell growth and differentiation (38), it may play a role in the morphological transformation of endothelial cells following KSHV infection.

Angiogenesis.

KS lesions are characterized by extensive neo-angiogenesis (37). This is reflected in our endothelial cell system by vessel-like aggregates of KSHV-infected spindle cells in cultures maintained for prolonged periods of time (data not shown). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a key role in angiogenic processes, and VEGF has been shown to be induced by virally encoded gene products including vIL-6, vGCR, vMIP-I, and vMIP-II (5, 9, 64, 98). Therefore, it is notable that the type 2 receptor for VEGF (VEGF-R2/KDR) was upregulated in our experiment since it suggests the possibility of an autocrine proangiogenic and proliferative stimulation. Upregulation of VEGF-R2 on KSHV-infected endothelial cells has been shown by others (42) and was confirmed on our KSHV-infected DMVEC by immunofluorescent staining (data not shown). Another upregulated gene confirmed by real time PCR in our system was that for the endothelial cell marker CD36, which is also expressed on KS spindle cells in vivo (89). CD36 is a multiligand scavenger receptor that binds to thrombospondin-1, collagen, oxidized low density lipoproteins, and long-chain fatty acids (40). Since thrombospondin is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis (105), the high level of CD36 induction in KSHV-infected cells could thus suggest a therapeutic mechanism to counteract KSHV-induced proangiogenic factors such as VEGF with exogenous thrombospondin.

Another important step in angiogenesis is extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling (for a recent review, see reference 79). The fibrinolytic plasminogen/plasmin system degrades most ECM-components. Plasminogen activator (uPA) cleaves plasminogen into plasmin, the active protease. Interestingly, the inhibitor of plasminogen activator was induced in KSHV-transformed DMVEC, whereas expression of uPA was repressed. This suggests that ECM degradation does not occur via plasminogen activation from KSHV-infected cells.

Cell division.

A number of genes that play a role during the cell cycle and DNA replication were upregulated in KSHV-infected cells. The KSHV-encoded viral cyclin, vCYC/ORF72, expressed in all latently infected cells, might play a role in these changes in cell cycle regulation (23, 104).

Tumorigenesis.

Carcinogenesis is often the result of aberrant cellular differentiation. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) is a ligand-activated nuclear receptor regulating adipocyte differentiation and carcinogenesis (39). PPAR-γ upregulation identified by microarray analysis was confirmed in real-time PCR experiments. The upregulation of PPAR-γ could be responsible for the regulation of several genes in our experiments since it has been shown that PPAR-γ agonists induce CD36 (108), plasminogen-activator inhibitor (55), and several genes regulating fatty-acid metabolism (39). In turn, PPAR-γ expression is upregulated by insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (87). IGFs are known inducers of endothelial cell differentiation and angiogenesis (10) and IGF-insulin receptor interactions have been implicated in various tumorigenic processes (6). Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs) bind to IGFs, modulating their interactions with insulin receptors (46). Increased IGFBP-2 levels have been associated with tumorigenesis (54), while IGFBP-6 is antitumorigenic. In this context, it is interesting that both the insulin receptor and IGFBP-2 were induced in KSHV infected DMVEC, while IGFBP-6 was downregulated, as observed both by microarray and PCR analysis. The IGF-pathway might thus be central to the transformation of endothelial cells by KSHV.

We also confirmed the induction of several additional genes with known functions in tumor development: c-kit, jun-D, and c-mer and the genes coding for inhibitor of DNA binding 1 (ID1) and LIM domain protein (LMO2). Jun-D belongs to the c-Jun family of DNA binding proteins. It is activated by several signaling cascades such as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and in turn activates a number of genes. ID family proteins are helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins whose overexpression is associated with proliferation and arrested differentiation in many cell lineages. c-mer is normally expressed during embryonic development and in the monocytic lineage but is aberrantly expressed in neoplastic T- and B-cell lines (45). In macrophages, c-Mer is thought to regulate uptake of apoptotic cells (95). The proto-oncogene LMO2 encodes a LIM domain transcription regulator that controls angiogenesis during mouse embryogenesis by regulating remodeling of the capillary network into mature vessels (112). The LMO2 gene is activated by chromosomal translocations in human T cell acute leukemias (81). The differential regulation of genes known to be involved in tumor formation following infection of DMVEC is consistent with the transforming potential of KSHV.

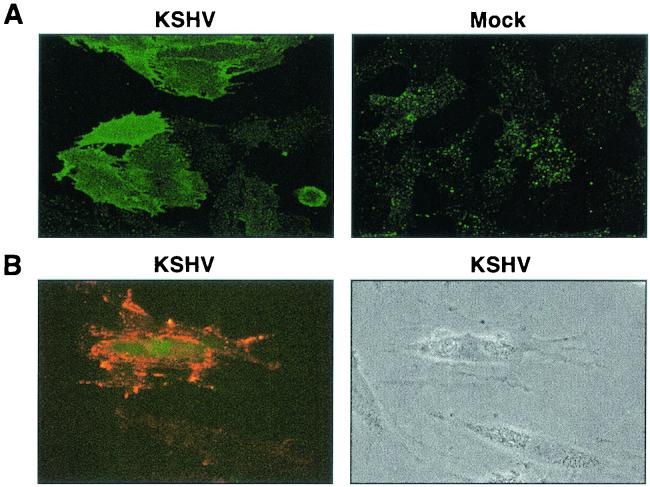

KSHV induces the surface expression of c-Kit.

The cDNA array analysis suggested many potentially important host-cell pathways that are modulated by KSHV during the transformation. We reasoned that some of these cellular genes would be crucial for KSHV-induced transformation. One of the genes that seemed a strong candidate for a pivotal role in endothelial cell transformation was the proto-oncogene c-kit. The c-Kit protein is a receptor tyrosine kinase for the ligand SCF, also known as steel factor or mast cell growth factor (67, 114). c-Kit induction by KSHV was of particular interest because c-Kit expression has been directly implicated in tumor etiology, due to activating mutations that allow ligand-independent activation, or coexpression of receptor and ligand leading to autocrine growth stimulation (12). c-Kit is normally expressed on hematopoietic cells, melanocytes, and germ cells but has also been detected in a variety of hematologic malignancies and solid tumors (63). Moreover, a recent study has also reported expression of c-Kit in KS tissue (69). Furthermore, a small molecule inhibitor of tyrosine kinase activity, STI 571 (Gleevec) that inhibits c-Kit activity (50) was available to examine a role for c-Kit in our in vitro system. c-Kit induction in KSHV-infected DMVEC was confirmed at the mRNA level by quantitative real-time PCR (Table 2) and at the protein level by immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) (Fig. 2A). To verify that c-Kit induction was independent of endothelial cell immortalization, IFA was also performed on primary DMVEC infected with a recombinant KSHV strain expressing GFP (110). In agreement with our previous observations, enhanced expression of c-Kit was observed on GFP-positive, KSHV-infected cells in the virus-exposed culture, but not on adjacent GFP-negative uninfected cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Induction of c-Kit protein on immortalized and primary DMVEC following KSHV infection. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy illustrating upregulation of c-Kit protein on the surface of E6/E7-immortalized KSHV-infected DMVEC monolayers (KSHV). In contrast, low levels of constitutive c-Kit expression were detected on mock-infected monolayers (Mock). Cells were stained for c-Kit at 3 weeks p.i., when ±60% of the culture was KSHV-infected. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy illustrating induction of c-Kit (red) on the surface of pDMVEC infected with GFP-KSHV (green) relative to constitutive levels of c-Kit expressed on adjacent uninfected cells in the same monolayer. The corresponding phase image is also shown. Cells were stained for c-Kit at 1 week p.i., when <50% of the cells were KSHV-infected. GFP expression indicates the KSHV-infected cell in the dark-field image.

Other studies have shown that endothelial cells from umbilical vein and aorta coexpress c-Kit and the SCF ligand (8, 16, 19, 113). To determine whether DMVEC expressed SCF in addition to c-Kit, we performed real-time RT-PCR analysis for SCF mRNA. The ratios for SCF-RNA levels in the four infected samples used in our real-time PCR analysis compared to the corresponding mock-infected cells are shown in Table 2. In contrast to c-Kit, there was no general tendency of SCF upregulation in KSHV-infected DMVEC. Due to alternative RNA splicing, the SCF protein exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms (41). We thus performed RT-PCR using isoform-specific primers to directly distinguish between membrane-bound and soluble SCF transcripts (49). Analysis of the RT-PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis indicated that the ratio of membrane-bound to soluble SCF in DMVEC is also unaffected by KSHV infection (data not shown). Moreover, analysis of DMVEC culture supernatants using a SCF-specific ELISA to measure secretion of SCF showed no significant changes in protein levels associated with KSHV infection (data not shown). Thus, if KSHV infection alters c-Kit/SCF-regulated signaling pathways, the contribution of virus infection is presumably at the level of c-Kit expression.

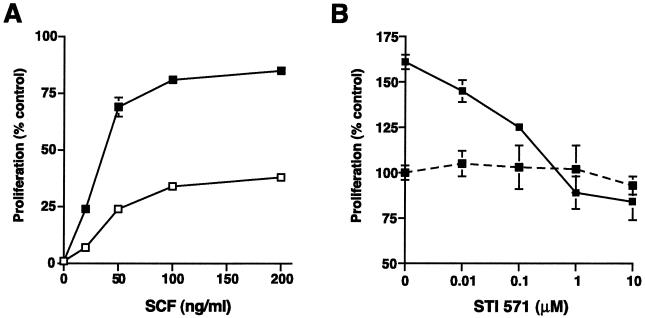

c-Kit expression in KSHV-infected DMVEC promotes proliferation in response to exogenous SCF.

To examine whether KSHV-induced upregulation of c-Kit had functional consequences, we tested whether the mitogenic response of DMVEC to exogenous SCF was enhanced following KSHV infection. Mock- and KSHV-infected DMVEC were cultured in growth factor depleted medium in the absence and presence of recombinant SCF and proliferation was measured using an XTT-based dye reduction assay (88). Both mock- and KSHV-infected DMVEC exhibited a dose-dependent proliferation in response to exogenous SCF that was maximal at 50 to 100 ng/ml. However, infected DMVEC were significantly more responsive to exogenous ligand than mock-infected DMVEC (Fig. 3A). In mock-infected cultures, the increase over basal proliferation in the absence of recombinant SCF was never more than 40%, while proliferation of KSHV-infected DMVEC was increased by as much as 85%. During KS disease, an enhanced capacity of KSHV-infected endothelial cells to respond to SCF produced by adjacent endothelial cells, or by macrophages and mast cells infiltrating the KS lesion, would promote more rapid growth of virus-infected cells.

FIG. 3.

SCF-dependent proliferation of DMVEC is enhanced by KSHV infection. (A) Proliferative response of mock (open squares)- and KSHV (filled squares)-infected DMVEC to exogenous SCF. Proliferation was measured using an XTT-based assay. Results from triplicate wells (± standard deviations [error bars]) are expressed as the percentage increase over basal proliferation measured in the absence of exogenous SCF. Representative results from one of three independent experiments are shown. (B) An inhibitor of c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity (STI 571) eliminates SCF-dependent DMVEC proliferation. KSHV-infected DMVEC were cultured in the presence of increasing doses of STI 571 and in the presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of exogenous SCF (50 ng/ml). Proliferation of KSHV-infected DMVEC was measured with an XTT-based assay as described above, but STI 571 was added at the same time as SCF (50 ng/ml). Results for triplicate wells (± standard deviations [error bars]) are expressed as a percentage of basal proliferation measured in the absence of SCF and STI 571 (expressed as 100%). Representative results from one of three independent experiments are shown.

The c-Kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI 571 inhibits the proliferation of KSHV-infected DMVEC.

To further substantiate a role for c-Kit/SCF in the enhanced growth response of KSHV-infected DMVEC, proliferation of infected DMVEC in response to exogenous SCF was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of an inhibitor of c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity, STI 571. STI 571 (Gleevec) was designed as an ATP-competitive inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase (17, 18, 35) and was later shown to be active against c-Kit (50). As illustrated in Fig. 3B, the proliferative response of KSHV-infected DMVEC to exogenous SCF was completely inhibited by a 1 μM dose of STI 571. Testing of DMVEC viability by trypan blue exclusion showed that growth inhibition was not due to nonspecific cytotoxicity of STI 571 (data not shown). In addition, STI 571 had no effect on the capacity of the human Jurkat T-cell line to proliferate in response to exogenous IL-2 (data not shown). The capacity of STI 571 to inhibit KSHV-infected DMVEC proliferation confirms a role for c-Kit signaling in the growth response of KSHV-infected cells and further suggests a novel strategy for KS therapy.

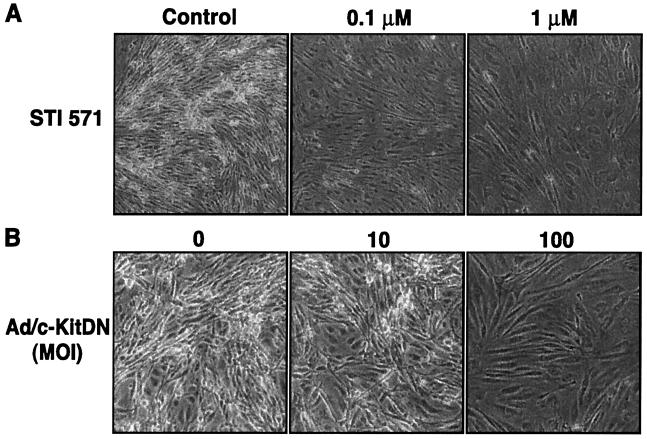

Inhibition of c-Kit activity reverses KSHV-induced transformation.

Induction of growth signaling loops is a frequently described consequence of abnormal c-Kit/SCF activity in tumor cell lines. In addition, enhanced c-Kit expression has been associated with changes in cell morphology and acquisition of a transformed phenotype (1, 21, 61). We previously demonstrated that KSHV-infected DMVEC develop a spindle phenotype and exhibit transformed characteristics including disorganized growth, focus formation and anchorage-independent growth in semisolid agar (71). To examine whether KSHV-induction of c-Kit also plays a role in virus-induced cell spindling and transformation, the consequence of inhibiting c-Kit signaling in KSHV-transformed DMVEC was evaluated. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, KSHV-transformed DMVEC exhibit disorganized growth, loss of contact inhibition and focus formation in monolayer culture. However, following treatment of DMVEC with STI 571 to inhibit endogenous c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity, focus formation was inhibited and an organized monolayer with distinct cell margins was reestablished. The effect of STI 571 was dose dependent and complete at a drug concentration of 1 μM. The loss of transformed growth characteristics was not due to drug-induced cytotoxicity since removal of STI 571 led to regeneration of the transformed phenotype, even after exposure of cells to a 10 μM dose (data not shown). Uninfected DMVEC exhibited normal growth with an organized cobblestone phenotype when maintained at confluency, and exposure to STI 571 had no effect on cell morphology or viability (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity reverses the transformed phenotype of KSHV-infected DMVEC. (A) KSHV-infected DMVEC exhibiting disorganized growth and focus formation were left untreated (Control) or treated with STI 571 (0.1 and 1 μM) for 5 days. The STI 571-induced focus loss and monolayer reorganization were observed and recorded with a Nikon light microscope. (B) KSHV-infected DMVEC exhibiting disorganized growth and focus formation were left untreated (0) or infected with an adenovirus vector expressing a dominant negative c-Kit protein (Ad/c-KitDN) at an MOI of 10 or 100 for 5 days, and the elimination of focus formation was recorded as for panel A. For both the pharmacological and dominant negative protein inhibition protocols, results from one of three independent experiments are shown. Fields photographed were representative of the entire monolayer of treated cells.

Because STI 571 is also active against the Abl and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) β receptor tyrosine kinases (18, 35), the inhibitory activity in DMVEC could imply a role for one or other of these receptors in KSHV-induced transformation. DNA microarray analysis of DMVEC did not reveal any KSHV-induced upregulation of Abl, PDGF or PDGF-receptor genes, suggesting that c-Kit was the primary drug target. However, to confirm a central role for c-Kit in KSHV-induced DMVEC transformation, we designed a complementary approach to specifically inhibit c-Kit signaling in KSHV-transformed DMVEC. In this approach, a dominant negative c-Kit protein (c-Kit DN) lacking the cytoplasmic ATP-binding and phosphotransferase domains necessary for c-Kit signaling was expressed in DMVEC using a previously described adenovirus delivery system (101). KSHV-infected DMVEC that exhibited pronounced focus formation were infected with an adenovirus vector expressing c-Kit DN (Ad/c-KitDN) along with an adenovirus expressing a transactivator (Ad/trans) necessary for induction of c-Kit gene expression. To control for infection efficiency and nonspecific effects of adenovirus infection, parallel DMVEC cultures were infected with an adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (Ad/GFP) and Ad/trans. In control cultures, these GFP were expressed at high levels in the majority of DMVEC but no change in the transformed phenotype was observed (data not shown). In contrast, expression of the dominant negative c-Kit protein in KSHV-transformed DMVEC resulted in a dramatic loss of transformed foci with cells flattening out and becoming organized in a manner identical to that observed following STI 571 treatment (Fig. 4B). The ability to reverse KSHV-induced morphological transformation through specific inhibition of c-Kit activity demonstrates a critical role for c-Kit signaling in KSHV-induced transformation of endothelial cells and supports a role for upregulation of c-Kit as a factor in KS tumorigenesis.

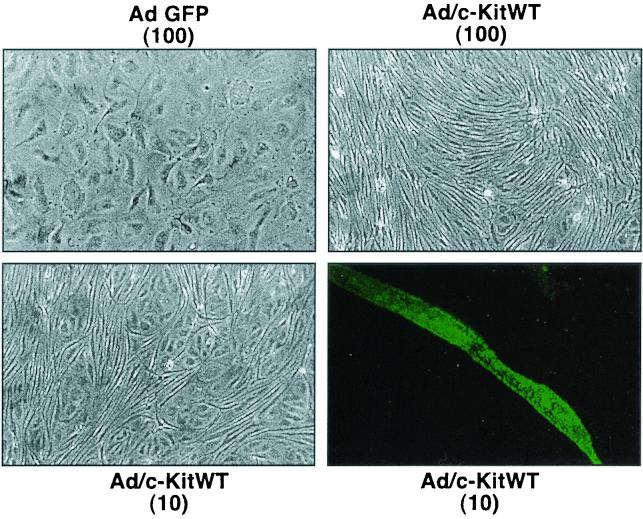

Expression of c-Kit in DMVEC is sufficient for induction of morphological transformation.

Ectopic expression of c-Kit in murine fibroblasts induces morphological alteration, growth in soft agar and tumorigenicity in nude mice (1, 21, 61). To determine whether c-Kit upregulation was sufficient to induce the morphological changes caused by KSHV infection, c-Kit was overexpressed in normal DMVEC in the absence of KSHV infection. The c-Kit overexpression was achieved by infecting DMVEC with an adenovirus vector expressing wild type c-Kit protein (Ad/c-KitWT) along with the adenovirus transactivator (Ad/trans) as described above. As illustrated in Fig. 5, c-Kit overexpression had a dose-dependent effect on DMVEC morphology that was highly reminiscent of that observed following KSHV infection. Ad/c-KitWT-infected cells became spindle-shaped and disorganized, with overgrowth of the monolayer and a loss of discrete cell borders. Morphological changes were first noted at day 5 postinfection (p.i.) and were prominent by day 10 p.i.. The changes were specific to adenovirus-infected cultures overexpressing c-Kit, since DMVEC infected with Ad/GFP were maintained for up to three weeks without phenotypic alteration. Immunofluorescent staining was performed on DMVEC infected with Ad/c-KitWT at a low MOI (MOI of 10) by use of an anti-c-Kit MAB followed by a FITC-conjugate to confirm that spindle formation was restricted to those cells that expressed high levels of c-Kit protein on the cell surface. Addition of exogenous SCF to Ad/GFP- or Ad/c-KitWT-infected DMVEC did not induce or accentuate morphological change, and adenovirus infection did not alter SCF production by DMVEC (data not shown). These results suggest that the endogenous SCF produced by DMVEC is sufficient to activate the pathways leading to morphological transformation. Importantly, these studies demonstrate that increased expression of c-Kit in DMVEC is sufficient to induce morphological changes comparable to those observed following KSHV infection of DMVEC.

FIG. 5.

Ectopic expression of c-Kit in normal DMVEC induces morphological changes. DMVEC monolayers infected with a control adenovirus vector expressing GFP (Ad/GFP) at an MOI of 100 maintain a normal cobblestone morphology. In contrast, DMVEC infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing c-Kit (Ad/c-KitWT) exhibit spindle morphology and disorganized growth. A dose-dependent effect was observed in DMVEC monolayers infected with Ad/c-KitWT at an MOI of 10, supporting the argument for a direct effect of c-Kit on spindle formation. This was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy on monolayers infected with Ad/c-KitWT at an MOI of 10. The dark-field enlargement illustrates strong expression of c-Kit protein specifically on a cell exhibiting spindle morphology.

DISCUSSION

DNA microarrays permit a global look at the transcriptional changes occurring during biological process such as carcinogenesis. One of the most promising applications for this technology is the classification of cancer and the dissection of molecular mechanisms of tumor progression (25, 32, 48, 52, 83). However, the identification of transcriptional changes also suggests novel possibilities for intervention. Since there is currently no known treatment for KS, our finding that upregulation of c-kit expression by KSHV is not only necessary but also sufficient for endothelial cell transformation suggests that the pharmacological inhibitor STI 571 (Gleevec) can be used to treat KS. STI 571 was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), where c-Kit is the effective target, and is in clinical trials for the treatment of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) where inhibition of c-Kit signaling successfully arrests the growth of SCLC cells in vitro (59, 111). Our study demonstrates the successful convergence of different technologies to enable transition from a complex in vitro model of viral pathogenesis to identification of relevant cellular genes that may constitute valid therapeutic targets.

The experimental system used here relied largely on KSHV-infected DMVEC cells that were immortalized with the E6 and E7 genes of HPV type 16 prior to KSHV infection. As we demonstrated earlier, the immortalized DMVEC retain expression of endothelial cell markers, grow as a cobblestone monolayer, and do not exhibit abnormal growth factor requirements (71). Moreover, this approach allowed us to compare infected and noninfected cell lines grown in parallel for the same time period, thus allowing for time-matched controls. However, since any E6/E7-induced changes in cellular gene profiles are controlled for by the relative comparison with mock-infected control cells, our analysis will not reveal genes regulated commonly by KSHV and E6/E7. Recently, Poole et al. compared the transcriptional profile of DMVEC transformed with KSHV to nontransformed primary DMVEC using Atlas DNA filter arrays and Incyte cDNA spotted arrays (80). Of the 124 genes that were upregulated in our study, Poole and colleagues confirmed RDC-1 and LMO2 by RT-PCR and 5 additional genes by array analysis (MEF2C, LGALS9, GJA1, IL-1R1, and SCYA14). Of the 60 downregulated genes in our study, Poole and colleagues confirmed 3 genes by array analysis (SDF1, PLAU, and TXNRD1). MCP-1 was found to be repressed in the study by Poole et al. However, our real-time PCR analysis confirmed MCP-1 upregulation in our experimental system. Similarly, UBE2C was upregulated in our study but downregulated in the Poole et al. study. With these two exceptions, genes that changed significantly in both studies showed the same tendency of up- or downregulation suggesting that each system identifies KSHV-regulated genes reliably.

In addition to genes that were changed in both experiments, each analysis identified genes that did not change or were not examined in the other assay. Of the remaining genes changing significantly in our analysis, 117 were not present on the cDNA arrays used by Poole et al. (http://pc190-10.kennedykrieger.org/microarraydata/). All other genes (57) were not observed to change in their study. Of the 313 genes that changed in the Poole et al. study, 96 were also tested in our system. Of these genes, 19 changed significantly in at least one of the infected cell lines. A possible reason for these discrepancies is that many more factors contribute to the exclusion of genes from this type of analysis than to their inclusion. For instance, although repeat experiments will dramatically lower the rate of false positives, they will not decrease the number of false negatives at the same rate, since signals that are not detected because of poor probe design will not become apparent simply by repeating the experiment. However, it is also possible that genes were excluded from our study because they were also altered due to E6/E7 expression. For example, transcriptional profiling of HPV-transformed keratinocytes has identified STAT-1 as one of the major downregulated genes with the consequence of a strong repression of the interferon-response genes (29). In contrast to Poole et al., we did not observe a strong induction of interferon-regulated genes upon KSHV infection. Since the same DNA array was able to detect ISG-induction by HCMV (97), we should have detected changes in ISG messages. A possible explanation could thus be that E6 and E7 counteract the interferon-inducing activity of KSHV.

Importantly, the dramatic transformation of endothelial cells, as evidenced by the change from a monolayer cobblestone phenotype to focus-forming spindle cell phenotype, was reflected in the large number of transcriptional changes over and above any changes due to E6/E7-immortalization. Particularly relevant to this process seems to be the large number of genes with known functions in cell proliferation and differentiation. One of the genes that was consistently upregulated and appeared to be a good candidate to test this assumption was c-kit. The upregulation of c-kit by KSHV was observed both in immortalized as well as primary DMVEC (Fig. 2). This further supports the use of the immortalized DMVEC to identify KSHV-induced cellular genes.

While c-Kit expression and c-Kit-SCF interactions are crucial for the normal development of hematopoietic cells and a restricted number of nonhematopoietic cells, expression of c-Kit has also been associated with a number of malignancies. In these c-Kit-associated malignancies, although distinct mutations of the c-Kit molecule are involved, all appear to be associated with an increased activity of the c-Kit/SCF signaling pathway. For example, in GISTs and germ cell neoplasms, gain-of-function mutations in juxtamembrane and tyrosine kinase domains have been described which permit, respectively, ligand-independent dimerization or constitutive activation without dimerization (53, 66, 76, 107). In SCLC and breast cancer, the observed coexpression of c-Kit and SCF is thought to generate an autocrine growth loop (51, 56, 58, 68, 109). As endothelial cells are the precursors of KS spindle cells, our finding that KSHV infection of dermal endothelial cells enhances c-Kit expression with a concomitant increase in c-Kit signaling activity indicates that c-Kit expression may also play an important role in the development and progression of KS. A recent study evaluating c-Kit expression in frozen samples of KS tissue by immunohistochemistry identified c-Kit expression in 2 of 13 samples examined (69). However, since fresh tissue was not available for examination by complementary methods or optimized histochemical procedures, c-Kit expression in additional samples may have been beyond the limits of detection. In addition, no information was presented regarding the clinical staging of the tumor tissue or the presence or activation state of the KSHV genome. Consequently, detection of c-Kit expression in at least some of the archival tissue studied supports an involvement for c-Kit expression in KS pathogenesis.

Our data demonstrate that both mock- and KSHV-infected DMVEC proliferate in response to exogenous SCF. However, the proliferative response to SCF was significantly greater in the KHSV-infected DMVEC than in uninfected cells. The more moderate response of uninfected DMVEC to exogenous SCF suggests that the level of c-Kit expression may be rate limiting for growth. In addition, stimulation of c-Kit by endogenous SCF and auxiliary regulation of receptor activity may also modulate proliferation. Similar observations on the proliferative response to exogenous SCF have been made for other cell types that coexpress c-Kit and SCF (51, 58, 109). For example, in a study of SCF-positive breast tumor subclones engineered to express different levels of c-Kit, only the cells expressing the highest levels of c-Kit responded to exogenous SCF (51). In our studies, the enhanced proliferative response of KHSV-infected DMVEC to SCF suggests that KSHV infection induces c-Kit expression to a level that enables an increased responsiveness to exogenous SCF.

In other cell systems, the c-Kit/SCF signaling pathway has been shown to play a role in cellular transformation as well as growth dysregulation. GISTs, which are though to originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal and are characterized by expression of c-Kit, commonly have a spindle cell or mixed epitheloid-spindle cell morphology (2). Also, ectopic expression of c-Kit in murine fibroblasts allows disorganized cell growth, loss of contact inhibition, and focus formation (1, 21, 61). Notably, such changes are reminiscent of those we have observed in KSHV-infected DMVEC (71). In GISTs, c-Kit mutations allow ligand-independent activation, while in the murine fibroblast system, exogenous ligand is required to induce transformation. In our DMVEC studies, the coexpression of SCF appears to facilitate an autocrine effect. The ability to reverse KSHV-induced phenotypic changes in DMVEC by inhibition of c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity strongly suggests that autocrine c-Kit/SCF interactions, in the context of increased c-Kit expression, play a role in cellular transformation. Furthermore, the phenotypic changes observed in DMVEC following c-Kit overexpression in the absence of KSHV infection further implicate KSHV-induced enhancement of c-Kit expression as a crucial event in DMVEC transformation.

Identification of a causative role for c-Kit in KSHV-associated cellular transformation suggests a novel therapeutic target for KS. The STI 571, the c-Kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor described in this report, is approved for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia, a disease associated with BCR-ABL kinase activity, and GIST, a disease associated with constitutive c-Kit activation. In conclusion, c-Kit should be considered a primary target in KS tumorigenesis. Consequently, STI 571, or other pharmacological inhibitors of c-Kit signaling, should be evaluated as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of KS.

Acknowledgments