Abstract

Background:

Women generally report greater sensitivity to pain than do men, and healthy young women require 20% more anesthetic than healthy age-matched men to prevent movement in response to noxious electrical stimulation. In contrast, MAC for xenon is 26% less in elderly Japanese women than in elderly Japanese men. Whether anesthetic requirement is similar in men and women thus remains in dispute. We therefore tested the hypothesis that the desflurane concentration required to prevent movement in response to skin incision (MAC) differs in men and women.

Methods:

Using the Dixon “up and down” method, we determined MAC for desflurane in 15 female and 15 male patients undergoing surgery (18–40 yr).

Results:

MAC was 6.2 ± 0.4% desflurane for women vs. 6.0 ± 0.3% for men (P = 0.31), a difference of only 3%. These data provide 90% power to detect a 9% difference between the groups.

Conclusion:

MAC of desflurane did not differ between young men and women undergoing surgery with a true surgical incision. While pain sensitivity may differ in women versus men, MAC of desflurane does not.

Summary Statement:

MAC for desflurane was similar in young adult women and men (6.2 ± 0.4% desflurane for women vs. 6.0 ± 0.3% for men; P = 0.31). This contrasts with previous results in which anesthetic requirement was based on the response to electrical stimulation and with studies showing that women report more pain than men.

Introduction

The Minimum Alveolar Concentration (MAC) is the alveolar (i.e., end-tidal) concentration of an inhaled anesthetic at which 50% of patients move in response to surgical incision.1,2 A key element of this definition is that skin incision is a supra-maximal stimulus that fully activates pain pathways. Movement in response to skin incision is an unconscious spinal reflex.3,4

Goto et al. report that xenon MAC for elderly Japanese women is 26% less than xenon MAC for elderly Japanese men.5 This would seem to conflict with the finding that women experience more pain than men after comparable noxious stimuli.6–9 This difference in pain sensitivity is pharmaco-dynamic rather than kinetic,10,11 and, therefore, implies the existence of complex, sex-based differences in the circuitry that modulates pain perception.

Consistent with increased pain sensitivity, we previously found that women required ≈20% more desflurane than men to suppress movement in response to 100 Hz, 65–70 mA stimulation, applied bilaterally for 10 seconds.12 Although such electrical current is unbearable without anesthesia, it is probably not supra-maximal since anesthetic requirement, as determined by this method may be less than that obtained using skin incision.13 In view of these apparently conflicting data, we tested the hypothesis that MAC for desflurane in women would differ from that in men.

Methods

In our previous study12 we found that the standard deviation of the anesthetic requirement for desflurane was 0.5% desflurane with an n of 10 subjects. We thus estimated that a total of 30 patients would provide an 85% power for detecting a 10% difference in MAC between the sexes.

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board and written informed consent, we enrolled 34 ASA Physical Status I and II patients aged between 18 and 40 years undergoing general anesthesia for elective surgery. We enrolled patients scheduled to have a skin incision greater than 3 cm (e.g., we excluded laparoscopic procedures).

Candidates having a history of chronic pain and those taking analgesic or sedative medications were excluded, as were those having a contraindication to an inhalation induction of anesthesia. We restricted enrollment to surgeries scheduled between 8 AM and noon to minimize the circadian influence on anesthetic requirement.14 We did not select patients based on their menstrual cycle.

Protocol

Patients were not given preoperative medications. Routine anesthetic monitors were applied. Anesthesia was induced by inhalation of 6–8% sevoflurane in 100% oxygen. The end-tidal concentration of the inhalational agent was measured with Datex-AS-3 monitor with an accuracy of 0.1%. A neuromuscular monitor was attached to the ulnar nerve to monitor “train-of-four” response. After loss of the lash reflex, succinylcholine was given intravenously. The patients’ lungs were ventilated with 80% oxygen, balance nitrogen and high concentrations of desflurane until all four twitches were lost. This time was used to remove sevoflurane from the lungs and replace it with desflurane. The trachea was then intubated.

An esophageal temperature probe was inserted. Forced air was used to maintain normothermia because MAC for volatile anesthetics decreases by 4–5% per degree-centigrade decrease in core temperature.15,16 The patients were maintained at their assigned end-tidal desflurane concentration for at least 10 minutes before skin incision with a fresh-gas flow of 3 L/min. Stimulation to the patient was avoided until incision. Patients’ lungs were ventilated with a tidal volume of 5–8 ml/kg. Before skin incision, we confirmed that the patient had recovered four full twitches in response to supra-maximal stimulation of the ulnar nerve at the wrist and that residual sevoflurane concentration was <0.1%. The first male and female patients studied were assigned to an end-tidal desflurane concentration of 6%. If this patient moved in response to surgical skin incision, the concentration was increased by 0.5% desflurane in the subsequent patient of that sex. In contrast, the desflurane concentration in the subsequent patient in that group was decreased by 0.5% if skin incision did not provoke movement. This paradigm is referred to as the “Dixon up-and-down” method.17

Measurements

Two independent investigators blinded to the end-tidal concentration of desflurane determined patient response to skin incision (movement or no-movement). One investigator observed the upper extremities and the other investigator observed the lower extremities and head of the patient. A positive response to skin incision was defined by a purposeful movement of one or more extremities or the head.3 Grimacing and coughing were not considered purposeful responses. Patients were observed for movement for one minute following skin incision.

Data Analysis

Our primary outcome was MAC, defined as the concentration of desflurane required to prevent movement in 50% of patients in response to skin incision. MAC was calculated as the average desflurane in each in each group for independent pairs of patients where one patient moved and the next did not.

Results in men and women were compared using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Data are presented as means ± SDs; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We considered differences in anesthetic requirement differing by less than 10% to be clinically unimportant.

Results

We enrolled 17 male and 17 female patients in the study. Data from two men and two women were deleted because of protocol violations: incision was made before the end of an adequate (10-minute) equilibration period in three patients, and opioid was inadvertently given before the incision in one patient. Analysis was thus restricted to the data obtained from the remaining 30 patients.

Demographic and morphometric characteristics did not differ between groups except for height, which was greater for men (Table 1). We had data on the menstrual cycle phases of 10 of the 15 women: These were equally divided between premenstrual, peri-ovulatory, and luteal phases of menstruation. The average time from induction of anesthesia to incision was 24 minutes in each group, which allowed us to maintain steady end-tidal desflurane concentrations for at least 10 minutes before incision. Core temperature and hemodynamic responses were similar in each group at the time of incision.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Potential Confounding Factors.

| Women (n=15) | Men (n=15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 163 ± 7 | 179 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 ± 8 | 27 ± 5 | 0.32 |

| Age (yr) | 33 ± 9 | 27 ± 8 | 0.10 |

| Time from Induction to Incision (min) | 24 ± 7 | 23 ± 10 | 0.91 |

| Core Temperature (°C) | 36.3 ± 0.5 | 36.1 ± 0.4 | 0.31 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 90 ± 19 | 97 ± 17 | 0.33 |

| Systolic Pressure (mmHg) | 112 ± 15 | 121 ± 13 | 0.10 |

| Diastolic Pressure (mmHg) | 69 ± 10 | 73 ± 12 | 0.25 |

Values below the line were obtained at the time of skin incision. BPM = beats per minute; BMI = body mass index. Data presented as means±SDs.

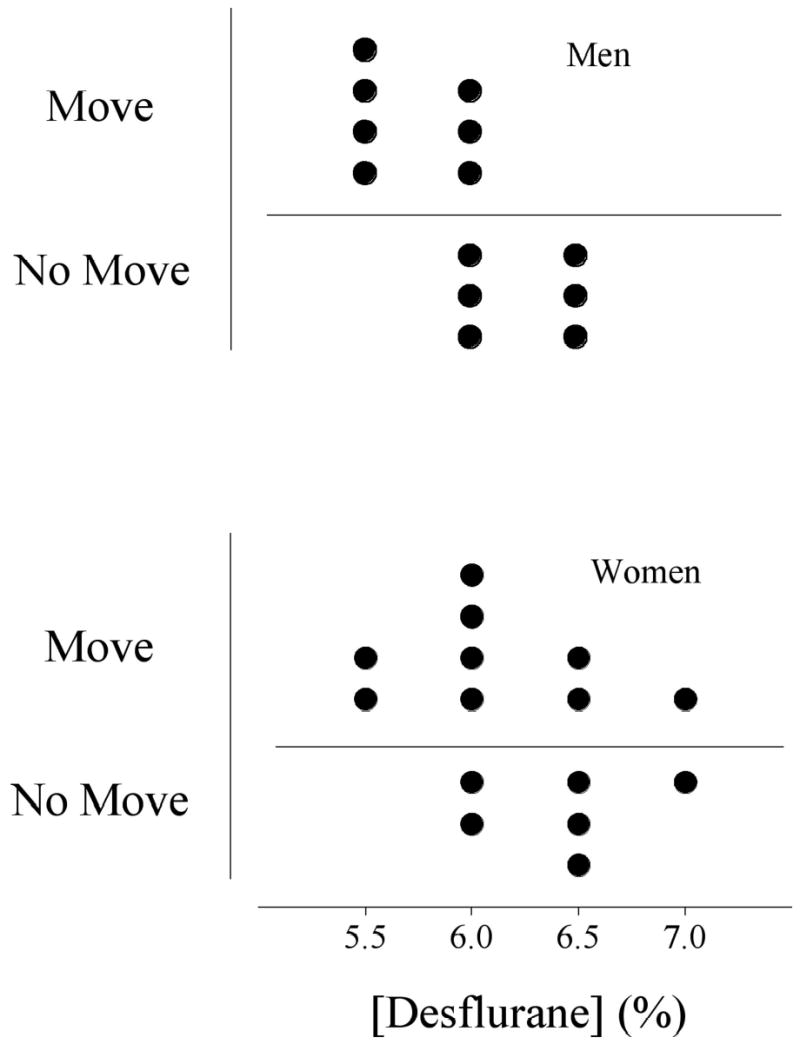

The average desflurane concentration required to prevent movement in 50% of the patients did not differ between women and men (Fig. 1). The MAC of desflurane was 6.2 ± 0.4% in women and 6.0 ± 0.3% in men (P = 0.31), a difference of 3%. These data provide 85% power to detect a 10% difference between the groups.

Fig. 1.

The end tidal concentrations of desflurane tested in men and women. Points above the horizontal line indicate movement whereas those below the line indicate no movement. MAC for desflurane in men was 6.0 ± 0.3%; in women it was 6.2 ± 0.4%, P = 0.31 (mean±SD).

Discussion

Estrogen and progesterone play a pivotal role in establishing the pain threshold during pregnancy and parturition,18–20 perhaps because female sex hormones modulate neuronal excitability via effects on the ion channels responsible for spinal and supra-spinal neurotransmission.21,22 It is therefore unsurprising that there appear to be sex differences in endogenous pain inhibitory circuitry in men and women. For example, women report both temporary and persistent pains more frequently than men8 and report greater pain in response to a given stimulus.7,9,23–25

The results of previous work from this laboratory found that women required 20% more desflurane than men to block reflex movement in response to electrical stimulation.12 However, desflurane MAC did not differ in the male and female participants in the current study. MAC values in both cases were about 6%, a value similar to that previously reported for patients of this age.26 These current results have a high degree of statistical power, indicating that there is less than a 10% chance that anesthetic requirement in men and women differ by more than 9%. It is thus unlikely that we simply failed to detect a true sex difference in MAC. Instead, differences between our previous and current protocols presumably explain the contrasting results.

The critical difference appears to be that Greif et al. used tetanic electrical shocks as the noxious stimulus rather than surgical skin incision.12 Although tetanic current at 65 mA is unbearable without anesthesia, anesthetic requirement, as determined by this method, is consistently less than that obtained by formal MAC testing.13 For example, the average desflurane requirement in Greif et al. was 5% whereas it was 6% in the current study, a difference of 20%. The key distinction here is that skin incision is a supra-maximal stimulus that fully activates pain receptors and pathways. Electrical stimulation is not, and it, therefore, provides graded activation of pain pathways.

It is worth noting, though, that there is little evidence that pain pathways are interrupted by volatile anesthetics. For example, MAC-BAR (minimum alveolar concentration of inhalation agent that blocks adrenergic responses to skin incision) considerably exceeds MAC.27 Furthermore, small concentrations of opioids substantially decrease MAC. And finally, the increase in ventilation prompted by skin incision is similar with either 1 or 2 MAC of isoflurane or halothane anesthesia.28 We must thus consider the possibility that our previous results are wrong.12

It remains unclear why our results differ so markedly from those reported recently by Goto et al. in which elderly Japanese women were found to require 26% less xenon than elderly Japanese men.5 Possibly the effects of xenon and desflurane on anesthetic requirement for men and women are dissimilar. Alternatively, there may be a sexual difference for Japanese women versus men but not for Caucasian women versus men. Age-related pharmacokinetic differences could also account for the discrepancy as well.26,29,30 MAC for inhalation anesthetics consistently decreases with age;26 this age-related change could be different in men than women since hormonal levels probably affect the efficacy of inhalation anesthetics. For example, women in early pregnancy have a decreased MAC for isoflurane, halothane, and enflurane compared to nonpregnant women.31 Thus, the altered hormonal milieu in the postmenopausal women may alter the response to inhalation anesthesia as well.

The pain threshold varies as a function of the menstrual cycle.32 Women have a higher pain threshold in the follicular phase than in the peri-ovulatory, luteal, or premenstrual phases. Women are most sensitive to ischemic, thermal, and pressure pain during the luteal phase.33,34 It is thus a limitation of our study that we included women in all phases of their menstrual cycles. Doing so may have increased response variability in the women. Nonetheless, the standard deviation in the women was relatively small, and the study was well powered to detect even small differences in anesthetic requirement. There remains a 10% chance that anesthetic requirement in men and women differ by as much as 9%. However, such small differences are of little clinical or physiological importance. Finally, the work of Tanifuji et al. suggests that the phase of the menstrual cycle is irrelevant to MAC, despite its effect on the perception of pain.35

In summary, the MAC of desflurane did not differ in young, healthy men and women. This result contrasts with previous results in which anesthetic requirement was based on the response to electrical stimulation. It also differs from studies showing that women report more pain than men. We thus conclude that while pain sensitivity is augmented in women, anesthetic requirement may not be.

Footnotes

Received from the Outcomes Research™ Institute and the Departments of Anesthesiology and Pharmacology, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40202.

Supported by NIH Grants GM 58273 and GM 061655 (Bethesda, MD) and the Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund (Louisville, KY). Mallinckrodt Anesthesiology Products, Inc. (St. Louis, MO) donated the thermocouples we used. We appreciate the assistance of Keith Hanni, M.D., Grigory Chernyak, M.D., Rainer Lenhardt, M.D., and Yunus Shah, M.D. (all from the University of Louisville). The authors thank Edmond Eger II, M.D. (University of California, San Francisco) for his insightful comments and suggestions. None of the authors has any personal financial interest related to this research.

References

- 1.Eger EI, Saidman IJ, Brandstater B. Minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration: A standard of potency. Anesthesiology. 1965;26:756–763. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saidman LJ, Eger EI, 2nd Effect of nitrous oxide and of narcotic premedication on the alveolar concentration of halothane required for anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1964;25:302–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rampil IJ. Anesthetic potency is not altered after hypothermic spinal cord transection in rats. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:606–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antognini JF, Schwartz K. Exaggerated anesthetic requirements in the preferentially anesthetized brain. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:1244–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto T, Nakata Y, Morita S. The minimum alveolar concentration of xenon in the elderly is sex-dependent. Anesthesiology 2002 Nov; (5):: 1129–32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fillingham R, Ness T. Sex-related hormonal influences on pain and analgesic responses. Neurosciences Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:485–501. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkley KJ. Sex differences in pain. Behav Brain Sci 1997; 20: 371–80; discussion 435–513. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–67. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarlani E, Greenspan JD. Gender differences in temporal summation of mechanically evoked pain. Pain. 2002;97:163–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gear RWGN, Heller PH, Paul S, Miaskowski C, Levine JD. Gender difference in analgesic response to the kappa-opioid pentazocine. Neurosci Lett. 1996;205:207–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepler KL, Standifer KM, Paul D, Kest B, Pasternak GW, Bodnar RJ. Gender effects and central opioid analgesia. Pain. 1991;45:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90168-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greif R, Laciny S, Mokhtarani M, Doufas AG, Bakhshandeh M, Dorfer L, Sessler DI. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of an auricular acupuncture point decreases anesthetic requirement. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:306–312. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebel PS, Glass PS, Fletcher JE, Murphy MR, Gallagher C, Quill T. Reduction of the MAC of desflurane with fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:52–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halberg J, Halberg E, Halberg F, E.M. Chronobiologic monitoring and analysis for anesthesiologists: Another look at a chronoanesthetic index. Advances in Chronobiology Part B. Edited by Puly JE, Scheving LE. New York, Alan R. Liss, Inc 1985: 315–322 [PubMed]

- 15.Regan MJ, Eger EI, 2nd Effect of hypothermia in dogs on anesthetizing and apneic doses of inhalation agents. Determination of the anesthetic index (Apnea/MAC) Anesthesiology. 1967;28:689–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eger EI, 2nd Age, minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration-awake. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:947–53. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon WJ. Quantal-response variable experimentation: The up-and-down method. Statistics in Endocrinology 1970: 251–267

- 18.Ginzler A. Endorphin-mediated increases in pain threshold uring pregnancy. Nature. 1980;210:193–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7414330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher JE, Thomas TA, Hill RG. Beta-endorphin and parturition. Lancet. 1980;1:310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genazzani AR, Facchinetti F, Ricci-Danero MG, Parrini D, Petraglia F, La Rosa R, D'Antona N. Beta-lipotropin and beta-endorphin in physiological and surgical menopause. J Endocrinol Invest. 1981;4:375–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03348298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss RL, Gu Q, Wong M. Estrogen: nontranscriptional signaling pathway. Recent Prog Horm Res 1997; 52: 33–68; discussion 68–9 [PubMed]

- 22.Wong M, Thompson TL, Moss RL. Nongenomic actions of estrogen in the brain: physiological significance and cellular mechanisms. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:189–203. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fillingham R, Maixner W. Gender differences in response to noxious stimuli. Pain Forum. 1995;4:209–221. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkley K, Holdcroft A. Berkley, K.J. and Holdcroft, A. Sex and Gender Differences in Pain. In: Wall, P.D. and Melzack, R. (eds) Textbook of Pain, 4th ed, Edinburgh:Churchill Livingstone, 1999, 951–965

- 25.Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1998;74:181–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mapleson WW. Effect of age on MAC in humans: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:179–85. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roizen MF, Horrigan RW, Frazer BM. Anesthetic doses blocking adrenergic (stress) and cardiovascular responses to incision - MAC BAR. Anesthesiology. 1981;54:390–398. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.France CJ, Plumer MH, Eger EI, 2nd, Wahrenbrock EA. Ventilatory effects of isoflurane (Forane) or halothane when combined with morphine, nitrous oxide and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46:117–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/46.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiyama T, Matsukawa T, Hanaoka K. The effects of age and gender on the optimal premedication dose of intramuscular midazolam. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:1103–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199805000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eger EI, 2nd. Desflurane animal and human pharmacology: aspects of kinetics, safety, and MAC. Anesth Analg 1992; 75: S3-7; discussion S8–9 [PubMed]

- 31.Chan MT, Mainland P, Gin T. Minimum alveolar concentration of halothane and enflurane are decreased in early pregnancy. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:782–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199610000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81:225–35. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veith JL, Anderson J, Slade SA, Thompson P, Laugel GR, Getzlaf S. Plasma beta-endorphin, pain thresholds and anxiety levels across the human menstrual cycle. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:31–4. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfleeger M, Straneva PA, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Girdler SS. Menstrual cycle, blood pressure and ischemic pain sensitivity in women: a preliminary investigation. Int J Psychophysiol. 1997;27:161–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(97)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanifuji Y, Mima S, Yasuda N, Machida H, Shimizu T, Kobayashi K. [Effect of the menstrual cycle on MAC] Masui. 1988;37:1240–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]