Abstract

The cellular levels of the alternative sigma factor σ54 of Pseudomonas putida have been examined in a variety of growth stages and culture conditions with a single-chain Fv antibody tailored for detection of scarce proteins. The levels of σ54 were also monitored in P. putida strains with knockout mutations in ptsO or ptsN, known to be required for the C-source control of the σ54-dependent Pu promoter of the TOL plasmid. Our results show that ∼80 ± 26 molecules of σ54 exist per cell. Unlike that in relatives of Pseudomonas (e.g., Caulobacter), where fluctuations of σ54 determine adaptation and differentiation when cells face starvation, σ54 in P. putida remains unexpectedly constant at different growth stages, in nitrogen starvation and C-source repression conditions, and in the ptsO and ptsN mutant strains analyzed. The number of σ54 molecules per cell in P. putida is barely above the predicted number of σ54-dependent promoters. These figures impose a framework on the mechanism by which Pu (and other σ54-dependent systems) may become amenable to physiological control.

Bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzymes are assembled by a common catalytic core enzyme that associates with a polypeptide (σ) conferring promoter recognition specificity. The majority of bacteria have alternative σ factors, most of which show homology with the major σ factor of Escherichia coli (σ70) (34). A different class is composed of a unique member (σ54, encoded by rpoN) that differs both in amino acid sequence and mechanism of transcription activation (5). In essence, σ54-RNAP holoenzyme forms a stable closed complex at the target promoter that is activated by a specialized family of regulators (20, 25) in a nucleotide (nucleoside triphosphate) hydrolysis-dependent manner (12, 26, 32).

A single copy of rpoN is found in the genome of many (but not all) bacterial species, including archetypical organisms such as E. coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus subtilis. In Pseudomonas putida, rpoN exists as a single copy (24) and its expression is subject to negative autoregulation (18). A variety of biological functions are regulated by σ54, although it appears that under favorable growth conditions these functions are dispensable since rpoN mutants are viable in all species tested except Myxococcus xanthus (17). The roles of σ54 vary among various microbial species, a fact reflected in the expression profiles of the factor. While in E. coli the intracellular levels of σ54 are constant throughout different growth stages (15), in Caulobacter crescentus the intracellular levels of σ54 oscillate according to growth conditions and cellular differentiation (4). Although P. putida does not have a differentiation program, the number of niches in which this species thrives (water, soil, and plant roots) is so diverse (30) that bacteria must undergo major changes in their global physiological status during adaptation to the disparate habitats. In addition, many strains of P. putida have a versatile metabolism for utilization of recalcitrant carbon sources (including aromatic compounds such as xylene or phenol), and the genes for this metabolism are often under the control of σ54-dependent promoters (e.g., the Pu promoter of TOL plasmid pWW0) (1). These promoters are subject to physiological regulation, becoming preferentially active at the stationary phase of growth (a phenomenon referred to as exponential silencing) (9), and modulation depending upon available carbon sources (i.e., C-source repression) (8, 10, 24, 27). Two genes, ptsO and ptsN, adjacent to rpoN in the P. putida chromosome, play a role in the C-source repression that glucose and gluconate exert on the Pu promoter (11). Both ptsN and ptsO encode homologues of phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system family proteins IIA(Ntr) and NPr, respectively.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the physiological control of σ54-dependent promoters is partially mediated through changes in σ54 activity and/or protein levels. For instance, overexpression of σ54 in P. putida allowed a partial relief of the exponential silencing of Pu (9). Also, modifications of the −12/−24 motif of Pu that improve its similarity to the consensus σ54 promoters have a positive effect on the transcription of this promoter in exponential phase (M. Carmona and V. Lorenzo, unpublished data). This suggests that recruitment of σ54-RNAP may be a limiting step for Pu activation in vivo as it occurs in vitro (7). Further, activation of σ54-dependent promoters in E. coli was found to depend upon the function of the specific protease FtsH, the lack of which can be compensated for by overproduction of the sigma (6).

The observations above highlight the importance of accurately quantifying the number of σ54 molecules present in P. putida at the different stages of growth and in culture media that influence Pu promoter activity. Although such quantification was partially attempted in the past (9), the poor quality of the polyclonal antiserum employed flawed the conclusions and left unanswered the question of the number of σ54 molecules per cell and the connection of σ54 to Pu activity, in particular the modulation of σ54 by C and N sources. By employing a dedicated phage antibody (Phab) displaying a single-chain Fv (scFv) antibody fragment with high affinity for σ54 from P. putida, we have determined accurately the number of σ54 molecules in P. putida cells at different growth stages and in various culture conditions. Our data indicate that σ54 is one of the most invariable and least abundant cell proteins, thereby restricting the mechanisms that may account for the physiological control of Pu.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, antibodies, and general procedures.

Standard methods were used to purify, analyze, manipulate, and amplify DNA (2). The E. coli strain XL-1 Blue (recA1 gyrA96 relA1 endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi1 lac [F′ proAB lacIq lacZΔM15 Tn10] Tcr; Stratagene) was used as a host for bacteriophages and phagemids. Phagemid pPC2 bears the sequence of the high-affinity anti-σ54 scFv named C2 assembled in vector pCANTAB-5Ehis (13) (details on scFv C2 are available upon request). scFv C2 specifically recognizes P. putida σ54 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and in Western blots. Depending on the conditions employed for proliferation, scFv C2 was produced as a distinct polypeptide or as a fusion with the pIII protein of the M13 phage. scFv-pIII hybrids were displayed as multiple copies on M13 particles (named Phab C2) by packaging the phagemids with Hyperphage (M13KO7ΔpIII, Kmr; Progen) (28). P. putida KT2442 and the P. putida ptsN::Km (10), ptsO::Km (11), and rpoN::Km (19) mutants were grown at 30°C in the indicated media: Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (29), M9 plus CAA (M9 containing 0.2% [wt/vol] Casamino Acids; Difco) supplemented or not with 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, high-nitrogen medium (M9 plus CAA supplemented with 0.2% succinate), and low-nitrogen medium (modified M9 medium containing 2 mM NH4Cl and supplemented with 0.2% succinate). The last two media were supplemented with 0.05% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 to avoid cellular clumping.

Protein analyses.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with standard protocols by using the Miniprotean system (Bio-Rad). Whole-cell protein extracts from Pseudomonas cells were prepared by harvesting the cells (10,000 × g, 5 min) from cultures grown in the indicated media and resuspending the cell pellet in 100 μl of H2O. Next, 100 μl of reducing 2× SDS sample buffer (120 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 2% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol) was added to the samples, and the samples were boiled for 10 min, sonicated briefly (∼5 s), and centrifuged (14,000 × g, 10 min) to eliminate the DNA viscosity and any insoluble material (e.g., peptidoglycans). Loading was normalized by the number of cells determined as CFU per milliliter after plating in LB-agar (1.5% [wt/vol]) or by the total amount of protein (protein assay kit; Bio-Rad). Usually ∼1.25 × 108 CFU or 10 μg of total protein was loaded per lane. Prestained standards (Kaleidoscope; Bio-Rad) were used as markers of known molecular weight for the SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) by using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad). After protein transfer, the membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature (or for 16 h at 4°C) with MBT buffer (3% skimmed milk, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]).

Immunodetection techniques.

For detection of σ54 with the purified scFv C2, membranes with the blotted proteins were incubated with 10 ml of MBT buffer containing 500 ng of the antibody. Unbound scFvs were eliminated by four washing steps of 5 min in 40 ml of PBS and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Next, anti-E-tag monoclonal antibody (MAb)-peroxidase (POD) conjugate (1:5,000 in MBT buffer; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to detect the bound scFvs. After 1 h of incubation, the membranes were washed four times with PBS and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20, the bound POD conjugates were developed by a chemiluminescence mixture of 1.25 mM luminol (Sigma) and 42 μM luciferin (Roche), and H2O2 was added at 0.0075% (vol/vol) in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). BM chemiluminescence blotting substrate (POD; Roche) was also used for developing the POD conjugates. After 1 min of incubation in the dark, the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was exposed to an X-ray film (X-Omat; Kodak). For immunodetection of σ54 with the M13 Hyperphage, the membranes were incubated with 30 ml of MBT buffer containing 5 × 1010 PFU of the phage. Unbound phages were eliminated by four washing steps of 5 min in 40 ml of PBS and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Next, anti-M13 MAb-POD conjugate (1:5,000 in MBT buffer; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to detect the bound M13 phages. After 1 h of incubation, the membranes were washed four times with PBS and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and the bound POD conjugates were developed with the BM chemiluminescence blotting substrate as described above. In order to standardize the protein amounts loaded in each case, duplicate blots were subjected to incubation with an anti-GroEL rabbit serum (1:5,000; kindly provided by J. M. Valpuesta, Centro Nacional de Biotecnología) and developed with anti-rabbit POD conjugate (1:5,000; Bio-Rad).

Quantification of σ54.

The intensity of light emitted by the protein bands in the membranes described above was quantified by employing the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) and matched with a standard developed by using purified σ54 protein (the kind gift of F. Bartels) run and processed under the same conditions. The absolute concentration of purified P. putida σ54 was determined by amino acid analysis for the standard curve. The protein sample was dried in a Speed-Vac (Beckman) and subsequently hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl-0.1% (vol/vol) phenol under vacuum conditions in a sealed glass tube for 24 h at 110°C. The amino acid analysis of the dried hydrolyzed protein sample was performed on a Beckman 6300 automatic analyzer to determine the amino acid composition as well as the protein concentration. Internal controls were performed with norleucine. This procedure allowed the accurate detection of 0.3 ng of σ54.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale for quantification of σ54 of P. putida in vivo with a single-chain antibody.

Antibody fragments assembled in M13 particles are particularly useful for the detection of proteins which are present in very small numbers in bacterial cells. This is because they can be either produced as distinct molecules or attached to phage particles (33). When the latter are employed as antibody-like agents, the use of a secondary anti-M13 coat antibody affords an extraordinary amplification from otherwise scarce target signals in the samples (22). Further, if the scFv is produced in an E. coli strain subject to infection with a hyper helper phage (28), then the resulting phage pool is composed of particles displaying multiple scFv units. This multiplies the operative affinity and specificity of the antibody. On this basis, the antibody named scFv C2, targeted towards σ54 of P. putida, has been instrumental (both as Phab C2 and as purified scFv) in monitoring and accurately quantifying the levels of the factor under various physiological circumstances. This quantification was possible by simply matching the signals from cell extracts with a signal response standard set with purified σ54 protein.

Levels of σ54 in P. putida cells at different growth stages.

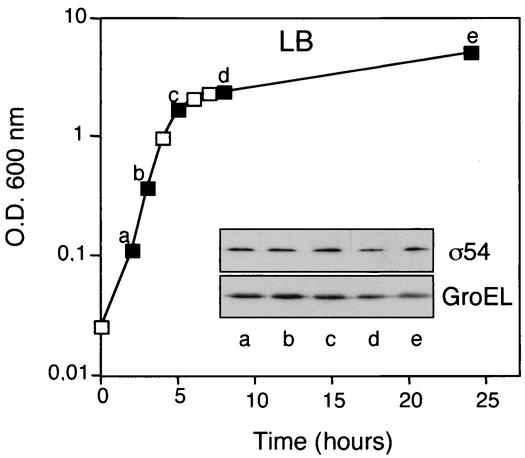

The levels of σ54 in P. putida cells were investigated at different points along the growth curve. To this end, P. putida cells were grown at 30°C in rich liquid media (LB) and aliquots were taken at different time points (Fig. 1). The protein extracts obtained from the cells were analyzed by SDS-10% PAGE and Western blotting by using multivalent Phab C2 for detection (see Materials and Methods). Loading of the gels was normalized so that 10 μg of total protein was applied per lane. Detection of GroEL polypeptide, whose levels per cell remain constant under these conditions, was employed as an internal control for normalization in the Western blots (Fig. 1, bottom inset). As shown in Fig. 1, the levels of σ54 in P. putida cells were constant along the growth curve, at both exponential and stationary phases.

FIG. 1.

Intracellular levels of σ54 in P. putida at different points along the growth curve. P. putida cells were grown in LB, and samples of these cultures were taken at different time points (filled squares). Whole-cell protein extracts derived from these cells were analyzed by Western blotting (∼10 μg of protein was loaded per lane). These membranes were probed with the multivalent Phab C2 for detection of σ54 (top inset) or with a polyclonal antiserum against GroEL as an internal control (bottom inset). O.D. 600 nm, optical density at 600 nm.

Nitrogen starvation does not affect σ54 concentrations.

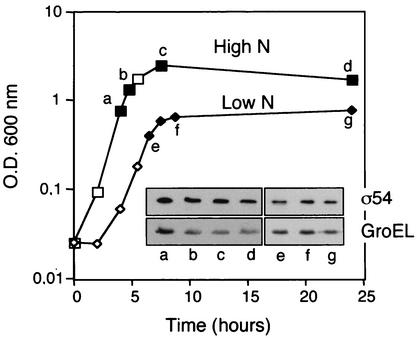

In E. coli cells, the activity of RpoN is essential for growth under nitrogen-limiting conditions. This is due to the requirement of the σ54 for the transcriptional activation of glnA, which encodes the glutamine synthase, an enzyme responsible for the assimilation of ammonia at low concentrations (ca. 1 mM) (23). Similar to E. coli, P. putida rpoN mutant cells are unable to grow in media containing a low concentration of ammonia as the sole nitrogen source (19). Although low ammonia concentration does not induce rpoN transcription (18), we speculated that nitrogen starvation could otherwise affect the levels of the σ54 polypeptide in P. putida. Thus, protein extracts from P. putida cells grown in defined mineral media having low (2 mM NH4Cl) or high (20 mM NH4Cl) nitrogen content were analyzed by Western blotting by using the multivalent Phab C2 (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 2, the intracellular content of σ54 polypeptide remained invariable during P. putida growth in media with high or low ammonia concentration, even when the cultures reached the stationary phase. These data demonstrate that nitrogen starvation does not affect the constant intracellular level of σ54 protein in P. putida.

FIG. 2.

Nitrogen starvation and σ54 levels in P. putida. Whole-cell protein extracts derived from P. putida cells grown in mineral media with high or low nitrogen content were obtained and analyzed by Western blotting as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Detection of σ54 and GroEL is shown in the top and bottom insets, respectively. O.D. 600 nm, optical density at 600 nm.

Effect of ptsN and ptsO mutations on levels of σ54 in P. putida.

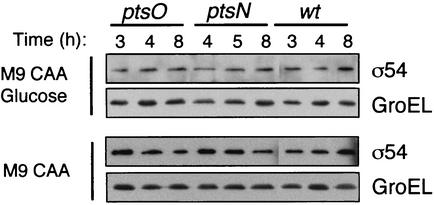

Mutation of ptsN or ptsO of P. putida, two genes adjacent to and downstream of rpoN, influences in opposite ways the C-source control of the Pu promoter from pWW0. In a ptsN mutant, the activity of Pu is not repressed by glucose, whereas a ptsO mutant strain displays a phenotype of Pu repression even in the absence of glucose (10, 11). Experimental evidence suggests the existence of an equilibrium between the phosphorylated forms of PtsO, an NPr-like enzyme, and PtsN, a IIA(Ntr)-like enzyme. It is believed that glucose increases the share of phosphorylated forms of PtsN, which is in turn responsible for the repression of Pu by an undisclosed mechanism (10). In this context, we investigated whether P. putida ptsN and ptsO mutant strains had altered intracellular levels of σ54 that could account for their phenotypes regarding the C-source repression of the Pu promoter. To this end, whole-cell protein extracts were prepared from P. putida KT2442 and the isogenic ptsN::Km and ptsO::Km strains, grown in M9 plus CAA medium supplemented or not with glucose (10 mM), and analyzed by immunoblotting with the multivalent Phab C2 as described above. The results from this experiment revealed that neither the presence of glucose nor the ptsO or ptsN mutation had an effect on the intracellular level of σ54 polypeptide in P. putida (Fig. 3). Therefore, these data prove that C-source repression of Pu in P. putida is unrelated to changes in the level of σ54.

FIG. 3.

Levels of σ54 in strains with mutations that affect the C-source regulation of Pu activity. Shown are Western blots to detect σ54 and GroEL (developed with Phab C2 and anti-GroEL serum, respectively) in whole-cell protein extracts (∼10 μg was loaded per lane) obtained from samples, harvested at the indicated time points, of cultures of wild-type (wt) P. putida and the isogenic ptsN and ptsO mutant strains grown in M9 plus CAA medium supplemented (top) or not (bottom) with 0.2% glucose.

Quantifying σ54 in P. putida cells.

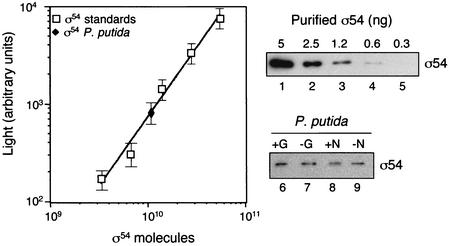

To accurately estimate the number of σ54 molecules per cell in P. putida, protein extracts derived from bacteria grown in different media (e.g., LB, M9 with high or low nitrogen concentration, and M9 plus CAA with and without glucose) were analyzed by quantitative Western blotting. In all cases, P. putida cells were harvested at stationary phase. In this assay, the signals obtained with purified scFv C2 against a series of twofold dilutions of purified σ54 (from 5 to 0.3 ng) were employed to generate a standard curve which allowed the precise determination of the amount of σ54 in the protein extracts normalized by numbers of CFU (Fig. 4). Quadruplicate experiments gave consistent results showing that ∼80 ± 26 molecules of σ54 exist per cell in P. putida, without significant variation with the different media analyzed. Interestingly, these numbers are within the range of, but lower than, those reported for E. coli (∼110 molecules/cell), which also remain roughly constant at exponential and stationary phases (15).

FIG. 4.

Quantification of σ54 in P. putida. The intensity of light emission after chemiluminescence developing of a Western blot containing five serial twofold dilutions of purified σ54 from P. putida (upper blot) was used to generate a standard curve for quantification of σ54 in P. putida cells. Total protein extracts were prepared from P. putida grown in LB (graph), as well as cells grown in M9 plus CAA supplemented (+G) or not (−G) with 0.2% glucose and media with high (+N) or low (−N) nitrogen content (lower blot). About ∼1.25 × 108 CFU was applied per lane of the gel (lanes 6 to 9). (Left panel) A standard curve is shown employing the log of the number of molecules of purified σ54 applied versus the log of the light intensity of their corresponding protein bands. The scFv C2 and anti-E-tag MAb-POD conjugate were used for detection as described above. Four independent experiments were performed and gave consistent results (standard deviation bars are included in the graph).

σ54 levels and physiological regulation of Pu.

The results presented above demonstrate that the level of σ54 in P. putida is altogether constant at ∼80 molecules/cell throughout any growth conditions. The number of σ54 molecules per P. putida cell is approximately twice the maximum number of σ54-dependent promoters predicted in the genome of P. putida (∼50 promoters; I. Cases et al., unpublished data). The low number of σ54 molecules is in contrast to the abundance of housekeeping sigma factor σ70 (∼750 molecules/cell in E. coli) (14). Because of this, it is plausible that the available pool of the σ54-containing form of the RNAP cannot saturate all σ54 promoters. Any condition that favors such an occupation may thus result in an increased output of the promoter under activation conditions. This framework, in which the artificial increase of σ54 levels relieves the physiological control of Pu (9), may simply reflect a higher occupation of the promoter by σ54-RNAP. Under normal in vivo conditions, σ54-RNAP alone fails to act on the Pu promoter and binding of the RNAP occurs only by virtue of the recruitment caused by the integration host factor (3, 7, 31). Sigma factor competition in stationary phase has been claimed as the major determinant of the physiological control of another related σ54-RNAP promoter of Pseudomonas called Po (16, 21). Since P. putida has as many as 24 sigma factors, versus the 7 found in E. coli (24), the role of sigma competition in controlling the promoter output in vivo may be more dramatic than anticipated (16, 21). A clear prediction of these notions is that promoters with high affinity for σ54-RNAP may not undergo much physiological control whereas those with a lower affinity may be amenable to additional regulatory checks to promote σ54-RNAP binding (Carmona and Lorenzo, unpublished). In any case, the low number of σ54 molecules may contribute decisively to the ability of the cells to rapidly adapt their metabolisms to changes in environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Frank Bartels (GBF, Germany) for his kind gift of purified σ54 from P. putida.

This work was supported by EU contracts ICA4-CT-2002-10011, QLK3-CT-2002-01933, and QLK3-CT-2002-01923, by grant BIO2001-2274 of the Spanish Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT), and by the Strategic Research Groups Program of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril, M. A., C. Michan, K. N. Timmis, and J. L. Ramos. 1989. Regulator and enzyme specificities of the TOL plasmid-encoded upper pathway for degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons and expansion of the substrate range of the pathway. J. Bacteriol. 171:6782-6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bertoni, G., N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and V. de Lorenzo. 1998. Active recruitment of sigma54-RNA polymerase to the Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida: role of IHF and αCTD. EMBO J. 17:5120-5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brun, Y. V., and L. Shapiro. 1992. A temporally controlled sigma-factor is required for polar morphogenesis and normal cell division in Caulobacter. Genes Dev. 6:2395-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck, M., M. T. Gallegos, D. J. Studholme, Y. Guo, and J. D. Gralla. 2000. The bacterial enhancer-dependent σ54 (σN) transcription factor. J. Bacteriol. 182:4129-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmona, M., and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. Involvement of the FtsH (HflB) protease in the activity of sigma 54 promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 31:261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona, M., V. de Lorenzo, and G. Bertoni. 1999. Recruitment of RNA polymerase is a rate-limiting step for the activation of the sigma(54) promoter Pu of Pseudomonas putida. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33790-33794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cases, I., and V. de Lorenzo. 2000. Genetic evidence of distinct physiological regulation mechanisms in the σ54 Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 182:956-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cases, I., V. de Lorenzo, and J. Perez-Martin. 1996. Involvement of sigma 54 in exponential silencing of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid Pu promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 19:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cases, I., J. Perez-Martin, and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. The IIANtr (PtsN) protein of Pseudomonas putida mediates the C source inhibition of the sigma54-dependent Pu promoter of the TOL plasmid. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15562-15568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cases, I., F. Velazquez, and V. de Lorenzo. 2001. Role of ptsO in carbon-mediated inhibition of the Pu promoter belonging to the pWW0 Pseudomonas putida plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 183:5128-5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon, R. 1998. The oxygen-responsive NIFL-NIFA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in gamma-proteobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 169:371-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández, L. A., I. Sola, L. Enjuanes, and V. de Lorenzo. 2000. Specific secretion of active single-chain Fv antibodies into the supernatants of Escherichia coli cultures by use of the hemolysin system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5024-5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihama, A. 2000. Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:499-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jishage, M., A. Iwata, S. Ueda, and A. Ishihama. 1996. Regulation of RNA polymerase sigma subunit synthesis in Escherichia coli: intracellular levels of four species of sigma subunit under various growth conditions. J. Bacteriol. 178:5447-5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jishage, M., K. Kvint, V. Shingler, and T. Nystrom. 2002. Regulation of sigma factor competition by the alarmone ppGpp. Genes Dev. 16:1260-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keseler, I. M., and D. Kaiser. 1997. sigma54, a vital protein for Myxococcus xanthus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1979-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Köhler, T., J. F. Alvarez, and S. Harayama. 1994. Regulation of the rpoN, ORF102 and ORF154 genes in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 115:177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köhler, T., S. Harayama, J. L. Ramos, and K. N. Timmis. 1989. Involvement of Pseudomonas putida RpoN sigma factor in regulation of various metabolic functions. J. Bacteriol. 171:4326-4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kustu, S., A. K. North, and D. S. Weiss. 1991. Prokaryotic transcriptional enhancers and enhancer-binding proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laurie, A. D., L. M. D. Bernardo, C. C. Sze, E. Skarfstad, A. Szalewska-Palasz, T. Nystrom, and V. Shingler. 2003. The role of the alarmone (p)ppGpp in sigma N competition for core RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1494-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindner, P., K. Bauer, A. Krebber, L. Nieba, E. Kremmer, C. Krebber, A. Honegger, B. Klinger, R. Mocikat, and A. Plückthun. 1997. Specific detection of His-tagged proteins with recombinant anti-His tag scFv-phosphatase or scFv fusions. BioTechniques 22:140-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magasanik, B. 1993. The regulation of nitrogen utilization in enteric bacteria. J. Cell. Biochem. 51:34-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Bueno, M. A., R. Tobes, M. Rey, and J. L. Ramos. 2002. Detection of multiple extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors in the genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and their counterparts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Environ. Microbiol. 4:842-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morett, E., and L. Segovia. 1993. The sigma 54 bacterial enhancer-binding protein family: mechanism of action and phylogenetic relationship of their functional domains. J. Bacteriol. 175:6067-6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Martin, J., and V. De Lorenzo. 1995. The amino-terminal domain of the prokaryotic enhancer-binding protein XylR is a specific intramolecular repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9392-9396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos, J. L., S. Marques, and K. N. Timmis. 1997. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid catabolic operons is achieved through an interplay of host factors and plasmid-encoded regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:341-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rondot, S., J. Koch, F. Breitling, and S. Dubel. 2001. A helper phage to improve single-chain antibody presentation in phage display. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Timmis, K. N. 2002. Pseudomonas putida: a cosmopolitan opportunist par excellence. Environ. Microbiol. 4:779-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valls, M., M. Buckle, and V. de Lorenzo. 2002. In vivo UV laser footprinting of the Pseudomonas putida sigma 54 Pu promoter reveals that integration host factor couples transcriptional activity to growth phase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2169-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss, D. S., J. Batut, K. E. Klose, J. Keener, and S. Kustu. 1991. The phosphorylated form of the enhancer-binding protein NTRC has an ATPase activity that is essential for activation of transcription. Cell 67:155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winter, G., A. D. Griffiths, R. E. Hawkins, and H. R. Hoogenboom. 1994. Making antibodies by phage display technology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:433-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wosten, M. M. 1998. Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]