Abstract

Multiple pterygium syndromes (MPSs) comprise a group of multiple-congenital-anomaly disorders characterized by webbing (pterygia) of the neck, elbows, and/or knees and joint contractures (arthrogryposis). In addition, a variety of developmental defects (e.g., vertebral anomalies) may occur. MPSs are phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous but are traditionally divided into prenatally lethal and nonlethal (Escobar) types. To elucidate the pathogenesis of MPS, we undertook a genomewide linkage scan of a large consanguineous family and mapped a locus to 2q36-37. We then identified germline-inactivating mutations in the embryonal acetylcholine receptor γ subunit (CHRNG) in families with both lethal and nonlethal MPSs. These findings extend the role of acetylcholine receptor dysfunction in human disease and provide new insights into the pathogenesis and management of fetal akinesia syndromes.

Multiple pterygia are found infrequently in children with arthrogryposis and in fetuses with fetal akinesia syndrome.1 Inheritance can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X linked, but autosomal recessive inheritance appears to be most common. Clinical expression is very variable, and, in the severest form, lethal multiple pterygium syndrome (LMPS [MIM 253290]), there is intrauterine growth retardation, multiple pterygia (e.g., chin to sternum, cervical, axillary, humero-ulnar, crural, popliteal, and ankles), and flexion contractures causing severe arthrogryposis and fetal akinesia. Subcutaneous edema can be severe, causing fetal hydrops with cystic hygroma and lung hypoplasia. Oligohydramnios and facial anomalies—in particular, cleft palate—are frequent. In addition, internal anomalies—including cryptorchidism, intestinal malrotation, cardiac hypoplasia, diaphragmatic hernia, obstructive uropathy, microcephaly, or cerebellar and pontine hypoplasia—are described.2,3 Although, in some cases, an underlying causative pathology of the brain, spinal cord, or skeletal muscle may be identified, in many cases, the etiology is not apparent.4 Inheritance is usually autosomal recessive. The second major type of multiple pterygium syndrome (MPS) is the milder, nonlethal Escobar variant (EVMPS [MIM 265000]). This is also characterized by multiple pterygia, arthrogryposis, facial dysmorphism, short stature, vertebral fusion, and other internal anomalies and is usually transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait.5,6

To our knowledge, the molecular basis for LMPS and EVMPS has not been characterized elsewhere, although linkage to two arthrogryposis loci was excluded in a large kindred with variant MPS.6 To identify a gene for MPS, we undertook genetic-mapping studies in a large Arab kindred (MPS001) with five affected individuals (see fig. 1). The proband, V-7, had pterygia of the elbows, axillae, poplitea, thumb, and neck and facial dysmorphism (ptosis, down-slanting palpebral fissures, and expressionless face) and rocker-bottom feet (fig. 2). In addition, he has some fused thoracic vertebrae, a large eventration of the right diaphragm, and normal intelligence. Two affected siblings died in the neonatal period (a sister died at age 3 mo because of congenital heart disease, and a brother died at age 3 d because of lung hypoplasia). The four living affected cousins (V-3, V-4, V-10, and V-12) were reported to have pterygia similar to that of the proband. We performed a genomewide linkage scan of affected individuals from the MPS001 kindred, by use of 5,572 SNPs from the Illumina SNP-based linkage IV panel. A single region of extended homozygosity shared by all affected individuals was then further analyzed by typing microsatellite markers in all 14 family members (5 affected) and in 4 members of a second family with EVMPS (MPS002) that contained two affected sisters born to a healthy first-cousin couple of Pakistani origin (fig. 1). After uneventful pregnancies and deliveries, both sisters were noted at birth to have neck pterygia, rocker-bottom feet, and clenched hands and to be mildly dysmorphic, with epicanthic folds. During childhood, they developed significant kyphoscoliosis that required surgery. Detailed review of one sister at age 22 years revealed facial dysmorphism (down-slanting palpebral fissures), high-arched palate, short stature (height 145.5 cm [<1st percentile], weight 48 kg [9th percentile]), kyphoscoliosis, relative macrocephaly (occipital-frontal circumference 75th–90th percentile), a short webbed neck, fixed flexion contractures at the proximal interphalangeal joints of all fingers, adducted thumbs with lack of skin creases at the distal interphalangeal joints of fingers 2–4, mild limitation of wrist extension, shoulder abduction and hip extension, webbing between the first and second fingers, and hypoplastic thenar eminences. Muscle bulk was good, with no demonstrable muscle weakness and no history of fatigue.

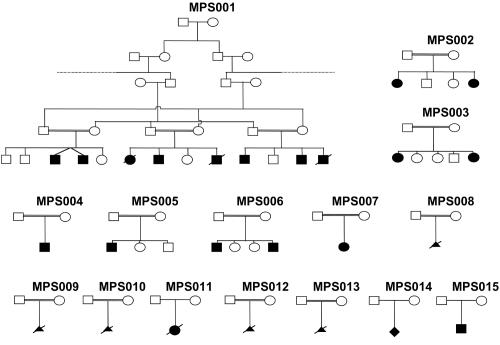

Figure 1. .

Pedigrees for families included in this study

Figure 2. .

Clinical features of subjects with CHRNG mutations and Escobar (A–H) and lethal (I and J) variants of MPS. An affected child from family MPS001 demonstrates an expressionless face and webbing of neck, axillae, and elbows (A); webbing of neck (posterior view) (B); thumb pterygium and camptodactyly (C); and popliteal pterygia and rocker-bottom feet (D). In family MPS015, an affected individual has neck pterygium (E) and pterygia and fixed flexion deformities at elbow (F), lower limbs (G), and hand (H). Elbow pterygium (I [arrow]) and muscle histopathology demonstrate an abnormal myotubular appearance (J) in a case of LMPS (from family MPS008).

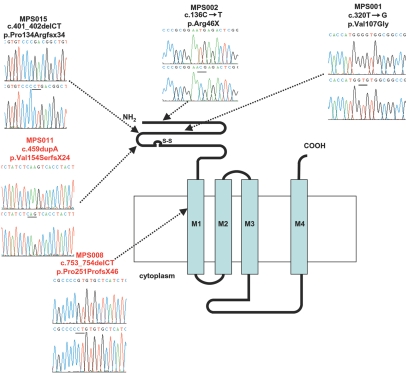

Genetic linkage studies confirmed a region of homozygosity at 2q36-q37 in affected individuals from both families. A common 6.68-Mb region of overlap between D2S1363 and D2S206 was identified, with a maximum two-point LOD score of 4.28 at recombination fraction (θ) 0 (under the assumption of equal allele frequencies) at D2S2193 for family MPS001 (fig. 3). We constructed an in silico genomic map of the region, using public databases (Ensembl Genome Browser), and prioritized genes for mutation screening on the basis of putative function and expression patterns. After failing to find mutations in a hypothetical gene, similar to tropomyosin 3 (TPM3), we analyzed CHRNG and identified a homozygous nonsense mutation in MPS002 (c.136C→T; p.Arg46X) and a missense substitution in MPS001 (c.320T→G; p.Val107Gly). Each of these acetylcholine receptor subunits comprises a large extracellular N-terminal ligand-binding region, three hydrophobic transmembrane domains, a large intracellular region, and a fourth hydrophobic domain (fig. 4). The c.136C→T mutation was predicted (in the absence of nonsense-mediated decay) to encode a 46-aa protein lacking the four transmembrane domains and intracellular loop domain (fig. 4). The c.136C→T mutation was not detected in 384 Asian control chromosomes, and the c.320T→G substitution was not present in 384 Asian and white (192 of each) and 84 Arabic control chromosomes. The p.Val107 residue is conserved in chimpanzee, cow, rat, mouse, chick, and frog CHRNG proteins.

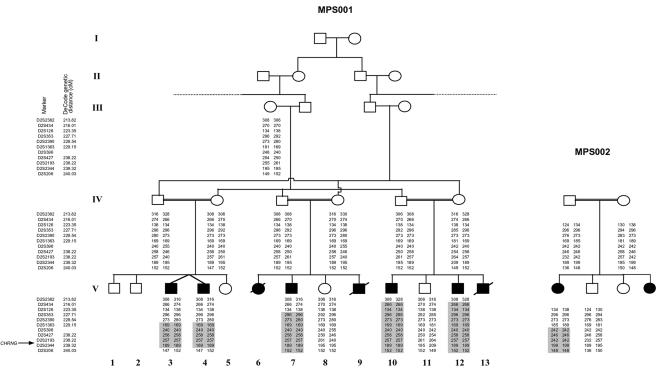

Figure 3. .

Identification of a common region of autozygosity in two families with MPS. The smallest region of overlap extended from D2S1363 to D2S206.

Figure 4. .

Localization of MPS mutations on the CHRNG gene product that comprises a large extracellular N-terminal ligand-binding region, three hydrophobic transmembrane domains, a large intracellular region, and a fourth hydrophobic domain. All mutations mapped to the extracellular or first transmembrane domains.

We then analyzed 13 further kindreds (7 with LMPS and 6 with EVMPS) for CHRNG mutations (see fig. 1 and table 1). In MPS015, a homozygous frameshift mutation (c.401_402delCT; p.Pro134Argfsx34) was identified in a 14-year-old boy with an EVMPS phenotype. He was born at 35 wk of gestation by emergency cesarean section because of fetal distress and decreased fetal movement, and he was ventilated from birth for 2 d because of poor respiratory effort. At birth, he was noted to have fixed flexion deformities with restricted movements at shoulder, elbow, wrist, finger, hip, and knee joints. Pterygia were present across large joints, from the neck to upper sternum, and at elbow, hip, and knee joints (see fig. 2). Intellectual development is normal. At age 18 mo, some paucity of facial expression and reduced muscle bulk with general mild weakness and absence of tendon reflexes were noted. A muscle biopsy at age 22 mo showed normal-sized fibers with normal peripheral distribution of nuclei. An increase in collagen, separating the muscle fibers into smaller-than-usual fascicles, was also noted. Muscle ultrasound showed extensive echogenicity in all muscles examined, in keeping with diffuse myopathy, and electromyography showed no evidence of active or progressive disorder but was clearly myopathic, with frequent low-amplitude, short-duration polyphasic potentials.

Table 1. .

Details of MPS-Affected Families with CHRNG Mutations and Sequence Variants[Note]

| Pedigree | Phenotype | Ethnic Origin | Nucleotide Alterations | Alterations in Coding Sequence | Exon/Intron | Parental Consanguinity |

| MPS001 | Nonlethal and lethal | Arab | c.320T→G | p.Val107Gly | 4 | Yes |

| MPS002 | Nonlethal | Pakistani | c.136C→T | p.Arg46X | 2 | Yes |

| MPS006 | Nonlethal | Pakistani | IVS4-9T→C | Unknown | IVS4 | Yes |

| MPS008 | Lethal | Turkish | c.753_754delCT | p.Pro251ProfsX46 | 7 | Yes |

| MPS011 | Lethal | Whitea | c.469dupA | p.Val154SerfsX24 | 5 | No |

| MPS015 | Nonlethal | Whitea | c.401_402delCT | p.Pro134Argfsx34 | 5 | No |

Note.— All patients were homozygous for the sequence alteration indicated.

From the United Kingdom.

Germline CHRNG-truncating mutations were found in two kindreds with LMPS (see table 1). A homozygous frameshift mutation (c.753_754delCT; p.Pro251ProfsX46) was identified in MPS008; a male fetus was found, on ultrasound scan at 13 wk of gestation, to have hydrops. The hydrops worsened, and the pregnancy was terminated at 15 wk of gestation. At autopsy, there was extensive loose skin over the body, consistent with severe hydrops prior to delivery, and facial dysmorphism, including down-slanting palpebral fissures, very-low-set ears, and marked micrognathia. There was marked deviation of the wrists and severe bilateral talipes. Internal examination revealed an unfixed colon, absent left umbilical, and a mild thoracic scoliosis. Muscle bulk was generally reduced, and muscle histology demonstrated an abnormal myotubular appearance (see fig. 2). A homozygous frameshift mutation (c.469dupA; p.Val154SerfsX24) (see table 1) was identified in a 37-wk female fetus (MPS011) found to be hydropic, with bilateral moderate pleural effusions, skin edema, and hydronephrotic right kidney. An emergency cesarean section was performed for fetal distress, but the baby died at age 1 d because of lung hypoplasia. At autopsy, contractures of all extremities, early webs in the groin and elbow, and rocker-bottom feet were noted. Internal examination revealed bilateral hydrothorax and lethal lung hypoplasia (with normal microscopy) and right pelvicalyceal dilatation. Muscle bulk appeared normal, and muscle histopathology was consistent with denervation (with slow fiber predominance, focal fiber-type grouping, and hypotrophic slow fibers together with some fat infiltration).

There was no apparent correlation between mutation position and clinical phenotype (see table 1 and fig. 4), and no evidence of germline CHRNG mutations were detected in five kindreds with LMPS or four kindreds with EVMPS. In eight of nine of these kindreds, linkage to CHRNG was excluded. However, we did detect a possible splice-site mutation, IVS4-9T→C, in the MPS006 kindred, in which two affected individuals had an EVMPS phenotype. Since CHRNG is expressed only in fetal or denervated cells, we were unable to study mRNA splicing, but the sequence change was absent in 192 ethnically matched control chromosomes, and allelotyping was consistent with linkage to CHRNG.

The pathogenesis of most forms of MPS has been unclear, although early-onset fetal akinesia, fragile collagen, and generalized edema have all been implicated. Thus, multiple pterygia may occur in Bruck syndrome, which is characterized by bone fragility and arthrogryposis multiplex and, in some cases, is caused by mutations in PLOD2, which catalyzes the hydroxylation of lysyl residues in collagens.7 However, in a review of lethal cases, only a few were found to have an underlying diagnosis (e.g., specific primary myopathy or metabolic or neurodevelopmental disorder), and there was considerable clinical and pathological heterogeneity.4 Hence, the finding that a substantial minority of cases of lethal and nonlethal MPS had germline CHRNG mutations represents a diagnostic advance and provides an insight into the etiology of MPS in these patients.

CHRNG encodes the γ subunit of the nicotinergic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) of skeletal muscle (CHRN in humans; Acr in mice). This pentameric transmembrane protein is composed of four different subunits and exists in two forms. The adult form is predominant in innervated adult muscle, and the embryonic form is present in fetal and denervated muscle. Embryonic AChR comprises two α and single β, γ, and δ subunits, whereas, in the adult AChR, the γ subunit is replaced by an ɛ subunit.8,9 In rodents, the switch from the γ to the ɛ subunit takes place in the first 2 wk of life, but, in humans, the switch occurs earlier and is apparently complete by 31 wk of gestation.10,11 The γ AChRs and ɛ AChRs have different conductances and opening times, such that the long, open-time γ AChRs generate random myofiber action potentials from miniature end-plate potentials, whereas the ɛ AChRs have shorter opening times and higher conductances.8,12

Elsewhere, mutations in AChR subunits have been associated with congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMS), genetic disorders of the neuromuscular junction that are classified by the site of the transmission defect (presynaptic, synaptic, and postsynaptic). Most are postsynaptic and are associated with AChR deficiency due to mutations in CHRNA1, CHRNB1, CHRND, or CHRNE.13,14 CMS are characterized by muscle weakness, fatigability, and a distinctive electromyographic pattern. The phenotype of CMS is distinct from that of MPS, although one patient with CHRND deficiency had arthrogryposis, and mild joint contractures may be associated with CMS caused by truncating mutations in rapsyn.15–17 CMS may also be caused by mutations in other genes, and these and other proteins implicated in acetylcholine synthesis might represent further candidate genes for MPS in families without CHRNG mutations.13,18,19

To our knowledge, mutations in CHRNG have not been described elsewhere in humans, although homozygous γ subunit–deficient mice were born alive and died at age 2 d because of suckling difficulty.12 Although these mice did not show pterygia and were able to move their forelimbs, their hindlimbs were immobile. Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by AChR antibodies. In women with MG, anti-AChR antibodies may cross the placenta, and ∼20% of infants born to mothers with MG have transient neonatal myasthenia. The severity of neonatal MG is highly variable, but, rarely, early antenatal onset may cause multiple joint contractures and reduced fetal movements. Such cases are associated with maternal autoantibodies against the embryonic form of the AChR.20,21 Since pterygia was not observed in these cases, it seems that the MPS phenotype results from early-onset fetal akinesia. Interestingly, antiembryonal AChR antibodies may result not only in arthrogryposis and features of fetal akinesia but may also be associated with abnormalities in the brain and heart.22 We note that the muscle histopathology associated with CHRNG mutations was variable and did not provide a consistent indicator for CHRNG inactivation, although this may be, to some extent, gestation dependent. However, the muscle histology is likely to depend on the timing of examination, and the postnatal changes may reflect the developmental effects of impaired prenatal neuromuscular transmission. Thus, AChR γ subunit–deficient mice do not exhibit the spontaneous muscle action potentials that are thought to play a role in developmental synapse and muscle maturation.11 However, despite the evidence for a key role of embryonal AChR function in normal prenatal muscle development, the γ subunit is not required postnatally and, consistent with this, patients with CHRNG mutations who survived the perinatal period did not demonstrate marked muscle weakness. In view of the differences in AChR biology (e.g., the timing of the γ and ɛ subunit switch) between humans and rodents, studies of the role of CHRNG mutations in MPS should provide further insights into the role of the γ AChR in normal human development and may elucidate a molecular basis for the phenotypic differences between lethal and Escobar variants.

Acknowledgments

We thank WellChild and the Wellcome Trust for financial support, and we thank the families and referring clinicians (including Maria Bitner and Kay Metcalfe) for their help with this research.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- Ensembl Genome Browser, http://www.ensembl.org/

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for LMPS and EVMPS)

References

- 1.Hall JG, Reed SD, Rosenbaum KN, Gershanik J, Chen H, Wilson KM (1982) Limb pterygium syndromes: a review and report of eleven patients. Am J Med Genet 12:377–379 10.1002/ajmg.1320120404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JG (1984) The lethal multiple pterygium syndromes. Am J Med Genet 17:803–807 10.1002/ajmg.1320170410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Froster UG, Stallmach T, Wisser J, Hebisch G, Robbiani MB, Huch R, Huch A (1997) Lethal multiple pterygium syndrome: suggestion for a consistent pathological workup and review of reported cases. Am J Med Genet 68:82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox PM, Brueton LA, Bjelogrlic P, Pomroy P, Sewry CA (2003) Diversity of neuromuscular pathology in lethal multiple pterygium syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol 6:59–68 10.1007/s10024-002-0042-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar V, Bixler D, Gleiser S, Weaver DD, Gibbs T (1978) Multiple pterygium syndrome. Am J Dis Child 123:609–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajab A, Hoffmann K, Ganesh A, Sethu AU, Mundlos S (2005) Escobar variant with pursed mouth, creased tongue, ophthalmologic features, and scoliosis in 6 children from Oman. Am J Med Genet A 134:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Slott AJ, Zuurmond A-M, Bardoel AFJ, Wijmenga C, Pruijs HEH, Sillence DO, Brinckmann J, Abraham DJ, Black CM, Verzijl N, DeGroot J, Hanemaaijer R, TeKoppele JM, Huizinga TW, Bank RA (2003) Identification of PLOD2 as telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase, an important enzyme in fibrosis. J Biol Chem 278:40967–40972 10.1074/jbc.M307380200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishina M, Takai T, Imoto K, Noda M, Takahashi T, Numa S (1986) Molecular distinction between fetal and adult forms of muscle acetylcholine receptor. Nature 321:406–411 10.1038/321406a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouzat C, Bren N, Sine SM (1994) Structural basis of the different gating kinetics of fetal and adult acetylcholine receptors. Neuron 13:1395–1402 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90424-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kues WA, Sakmann B, Witzemann V (1995) Differential expression patterns of five acetylcholine receptor subunit genes in rat muscle during development. Eur J Neurosci 7:1376–1385 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hesselmans LF, Jennekens FG, Van den Oord CJ, Veldman H, Vincent A (1993). Development of innervation of skeletal muscle fibers in man: relation to acetylcholine receptors. Anat Rec 236:553–562 10.1002/ar.1092360315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi M, Kubo T, Mizoguchi A, Carlson CG, Endo K, Ohnishi K (2002) Spontaneous muscle action potentials fail to develop without fetal-type acetylcholine receptors. EMBO Rep 3:674–681 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel AG, Ohno K, Shen XM, Sine SM (2003) Congenital myasthenic syndromes: multiple molecular targets at the neuromuscular junction. Ann NY Acad Sci 998:138–160 10.1196/annals.1254.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurkat-Rott K and Lehmann-Horn F (2005) Muscle channelopathies and critical points in functional and genetic studies. J Clin Invest 115:2000–2009 10.1172/JCI25525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brownlow S, Webster R, Croxen R, Brydson M, Neville B, Lin J-P, Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J, Beeson D (2001) Acetylcholine receptor δ subunit mutations underlie a fast-channel myasthenic syndrome and arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. J Clin Invest 108:125–130 10.1172/JCI200112935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke G, Cossins J, Maxwell S, Owens G, Vincent A, Robb S, Nicolle M, Hilton-Jones D, Newsom-Davis J, Palace J, Beeson D (2003) Rapsyn mutations in hereditary myasthenia: distinct early- and late-onset phenotypes. Neurology 61:826–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeson D, Hantai D, Lochmuller H, Engel AG (2005) 126th International Workshop: congenital myasthenic syndromes, 24–26 September 2004, Naarden, the Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord 15:498–512 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohno K, Brengman J, Tsujino A, Engel AG (1998) Human endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency caused by mutations in the collagen-like tail subunit (ColQ) of the asymmetric enzyme. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 95:9654–9659 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeChiara TM, Bowen DC, Valenzuela DM, Simmons MV, Poueymirou WT, Thomas S, Kinetz E, Compton DL, Rojas E, Park JS, Smith C, DiStefano PS, Glass DJ, Burden SJ, Yancopoulos GD (1996) The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell 85:501–512 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81251-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernet-der Garabedian B, Lacokova M, Eymard B, Morel E, Faltin M, Zajac J, Sadovsky O, Dommergues M, Tripon P, Bach J-F (1994) Association of neonatal myasthenia gravis with antibodies against the fetal acetylcholine receptor. J Clin Invest 94:555–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent A, Newland C, Brueton L, Beeson D, Riemersma S, Huson SM, Newsom-Davis J (1995) Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita with maternal autoantibodies specific for a fetal antigen. Lancet 346:24–25 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92652-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polizzi A, Huson SM, Vincent A (2000) Teratogen update: maternal myasthenia gravis as a cause of congenital arthrogryposis. Teratology 62:332–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]